The Driftless Region came into my awareness several years ago when I worked in a Rock Shop in Sedona.

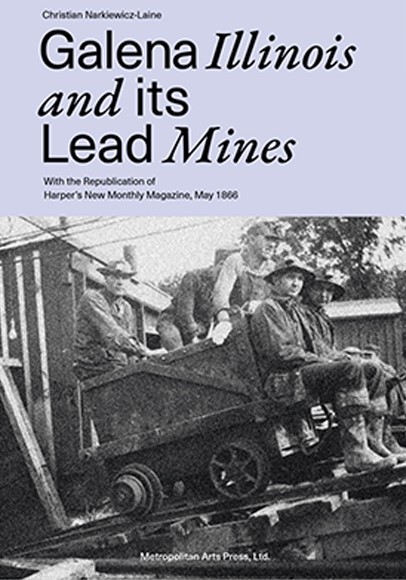

There were pieces of galena in the display case from the Driftless Region.

Galena is the natural mineral form of lead sulfide, and the most important ore of lead and an important source of silver.

I found the name “Driftless” to be intriguing, so I looked into it briefly at the time.

This would have been sometime during 2017 or 2018.

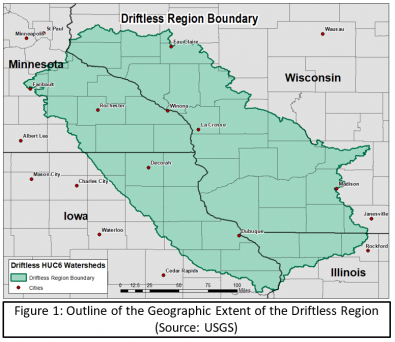

We are told it was called the “Driftless Region” because it was by-passed by the last glacier on the continent and lacks glacial drift.

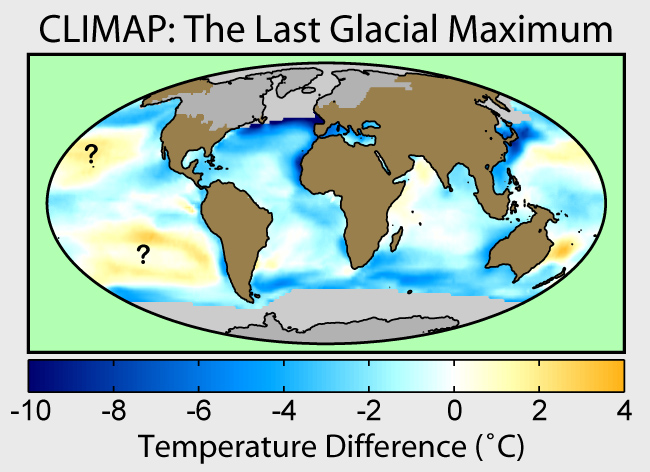

The last ice age is known to us as the Pleistocene Epoch, defined typically as a period of time beginning about 2.6-million-years-ago and lasting until about 11, 700 years ago, and the epoch during which homo sapiens evolved.

We are told that during the Pleistocene Epoch, the continents had moved to their current positions on the Earth, and glacial sheets of ice covered Antarctica, as well as large parts of Europe, North America, South America, and small parts of Asia.

The glaciers didn’t just sit there, as we are given the explanation that there was much movement over time, apparently with 20 cycles of the glaciers advancing and retreating as they thawed and refroze.

The name Pleistocene first came into use, a combination of the Greek words for “most recent,” with Sir Charles Lyell, a Scottish geologist who was said to have demonstrated the power of known natural causes in explaining Earth’s history.

In his books, “The Principles of Geology,” published in three volumes between 1830 and 1833, he presented the idea that the Earth was shaped by the same natural processes that are still operating today at similar intensities, and a s such a proponent of “Uniformitarianism,” a gradualistic view of natural laws and processes occuring at the same rate now as they have always done.

This theory was in contrast to “catastrophism,” or theory that Earth has been shaped by sudden, short-lived violent events of a worldwide nature.

At any rate, as a result of Lyell’s work, the glacial theory gained acceptance between 1839 and 1846, and we are told during that time, scientists started to recognize the existence of ice ages.

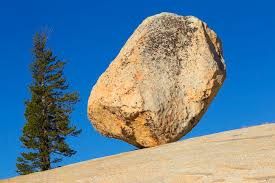

The concept of “glacial erratic” has come to be the explanation for large masses of rock that have been moved by glacier ice and lodged in glacier valleys or scattered over hills.

Examples include the rectangular Madison Boulder in New Hampshire is considered to be one of the largest glacial erratics in the world, at 83-feet, or 25-meters, long, and 23-feet, or 7-meters, high, and upwards of 5,000 tons, with one part of it said to be buried to a depth of up to 12-feet, or 4-meters.

It is interesting to note the number of glacial erratics that end up either perfectly balanced by themselves…

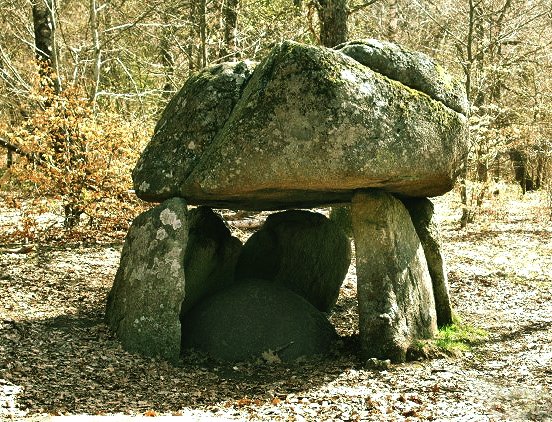

…or as a large block of stone balanced on top of smaller stones.

The exact same idea is called a dolmen in other parts of the world, and is considered the the most common megalithic structure in Europe, believed to be a tomb or burial space.

Cataclysmic flooding during the the last ice age was given the credit for creating the “Channeled Scablands” in the southeastern part of Washington State…

…but I really think these geologic explanations were a way to falsely attribute natural forces to explain and cover-up ancient, man-made stonework.

So, since we are told it was called the “Driftless Region” because it was by-passed by the last glacier on the continent and lacks glacial drift, lets see what we find here.

Thanks in advance to all who left suggestions of places to look here in the comments section.

I am going to start my journey through the Driftless Region in Nauvoo, Illinois.

Nauvoo was the main gathering place for Joseph Smith and the Mormons after their expulsion from Missouri.

Joseph Smith was the founder of Mormonism.

In 1830, he published “The Book of Mormon” and organized his church in New York, the same year Sir Charles Lyell published the first volume of “The Principles of Geology.”

Joseph Smith had a series of visions as a young man, and in one of the visions, he was directed by an angel to a buried book of golden plates engraved with a Judeo-Christian history of an ancient American civilization, of which The Book of Mormon was his translation of the information contained on the golden plates.

Joseph Smith and his followers left New York, and moved west in 1831 to build an American Zion, which within Mormonism has multiple meanings, including the central physical locations the Mormons have gathered, including Kirtland, Ohio; Jackson County, Missouri; Nauvoo, Illinois; Zarahemla, Iowa; and the Salt Lake Valley in Utah.

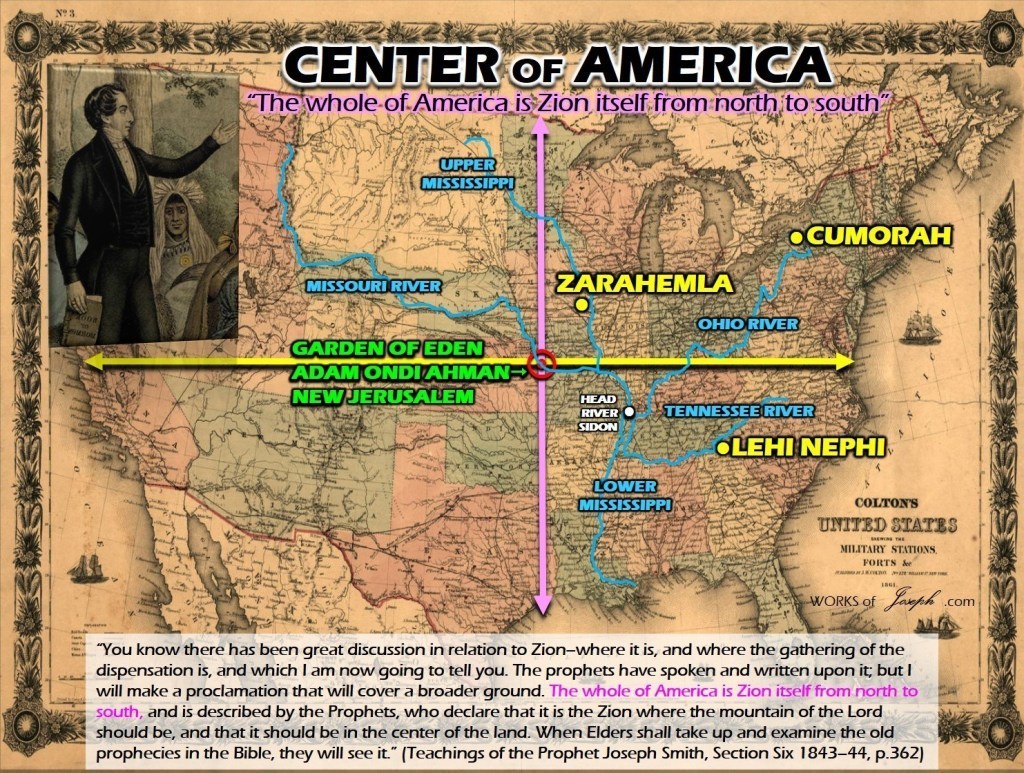

…and according to Joseph Smith, the entirety of the Americas was Zion.

Zarahemla refers to a large city in the Ancient Americas described in The Book of Mormon.

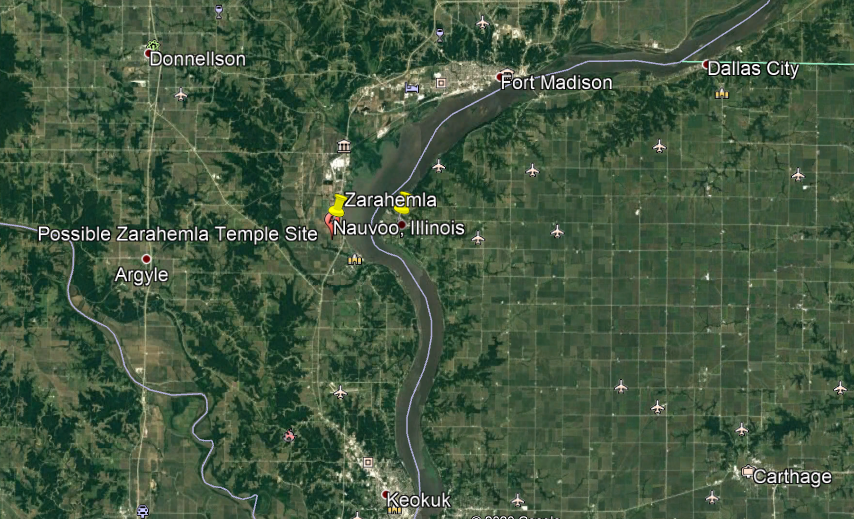

While the exact location of Zarahemla is not known, there was a Mormon settlement named Zarahemla in Iowa directly across the Mississippi River from Nauvoo, and where there is an excavation of what might be Zarahemla.

There appear to be geometric and astronomical alignments between the possible location of the Zarahemla temple and the city of Nauvoo, with an equinoctial alignment between the proposed Zarahemla Temple site and the Nauvoo Temple.

This is what we are told about the Nauvoo Temple.

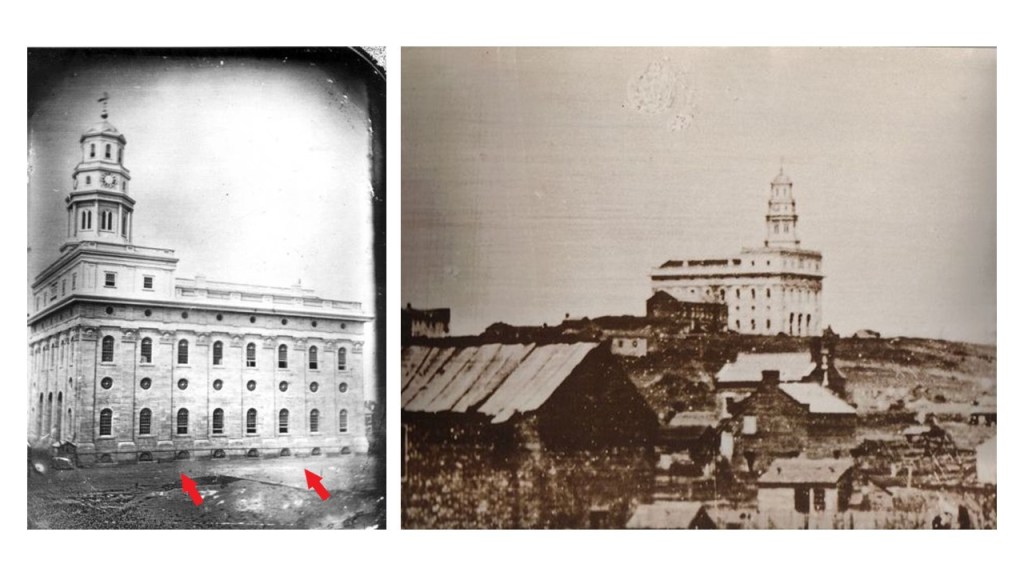

It was the second temple constructed by the Mormons, with its cornerstone being laid on April 6th of 1841, and it was designed in the Greek Revival style by architect William Weeks under the direction of Joseph Smith.

Its construction was said to have been completed under the leadership of Brigham Young and in use by the winter of 1845.

Interesting to see the windows at ground-level in the photo of the temple on the left, and the wooden shacks in the foreground in contrast to the limestone building in the background.

On June 27th of 1844, Joseph Smith and his brother Hyrum were in jail in Carthage, Illinois awaiting trial on charges including inciting a riot in Nauvoo, when they were both killed by an armed, anti-Mormon mob that stormed the jail building.

The Nauvoo Temple was only in use by the Mormons for three months, as they Mormons ended up leaving Nauvoo under Brigham Young’s leadership for the Salt Lake Valley in Utah because of increasing anti-Mormon violence and sentiments in that part of Illinois.

The Nauvoo Temple was said to have set on fire an unknown arsonist around midnight of October 8th and 9th of 1848, gutting the temple.

Whatever was left standing of the temple was said to have been completely demolished in 1865.

Then in 1999, the Mormon Church president at the time announced that the Nauvoo Temple would be built on its original footprint, and by June of 2002, a replica of the original temple was dedicated.

Interesting to note that in the 2010 census, Nauvoo’s population was only 1,149.

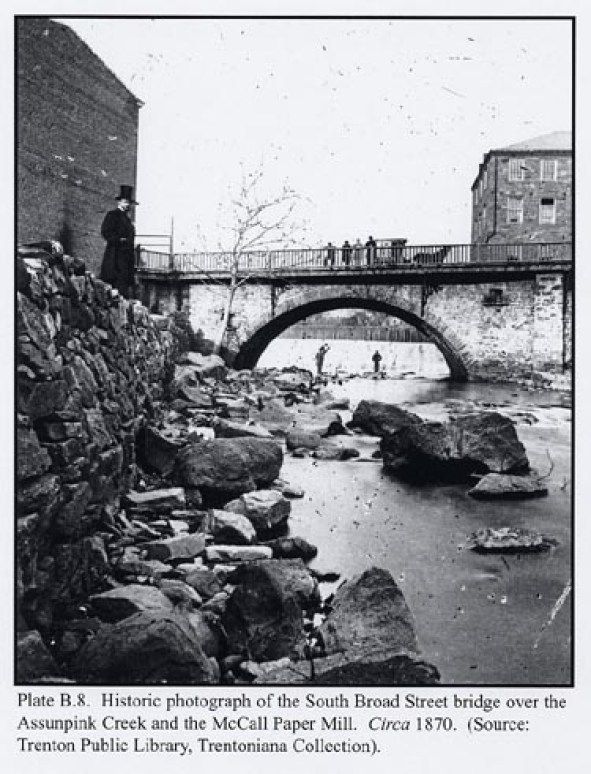

The stone arch bridge in Nauvoo was said to have been built by Mormon settlers in 1850.

Keokuk in Iowa is just a short-distance southwest of Nauvoo, and is the location of the Des Moines Rapids Canal, located on the Mississippi River.

The construction of the 12-mile-long Des Moines Rapids Canal was said to have started in 1866, one year after the end of the American Civil War, and completed in 1877.

Then it is said to have been in use for only 36 years, closing in 1913.

Like what we are told about the Nauvoo Temple, does any of this make sense with the amount of effort and expertise that would be needed to construct a massive engineering project like this?

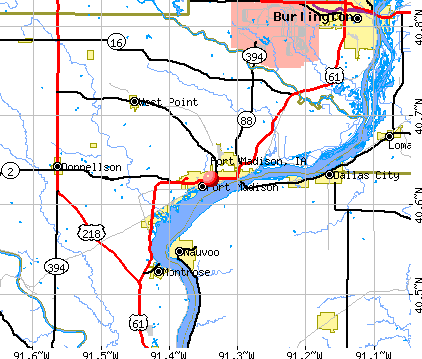

Fort Madison, Iowa is just a short-distance up the Mississippi River from Nauvoo.

Here is a historic bank building in Fort Madison…

…compared with the historic Alberta Hotel in Edmonton, Alberta…

…and the Richardson Building in Burlington, Vermont.

This is a wall of the Iowa State Penitentiary at Fort Madison…

…compared with this wall of the Cardiff Castle in Wales.

This is said to be the original fortification on the grounds of Cardiff Castle, which is said to have been built in the late 11th-Century, after the Norman Conquest by William the Conqueror in 1066.

It is what is called a motte-and-bailey castle, but looks suspiciously like a mound to me.

For comparison, this is Silbury Hill, called a prehistoric artificial chalk hill in Wiltshire.

It is part of a complex of Neolithic monuments, and located a short driving distance from the Avebury Stone Circle.

It is considered the largest man-made structure in Europe, believed to date back to 2,400 BC…

…and a popular place for crop circles…

…and other geometric shapes to appear.

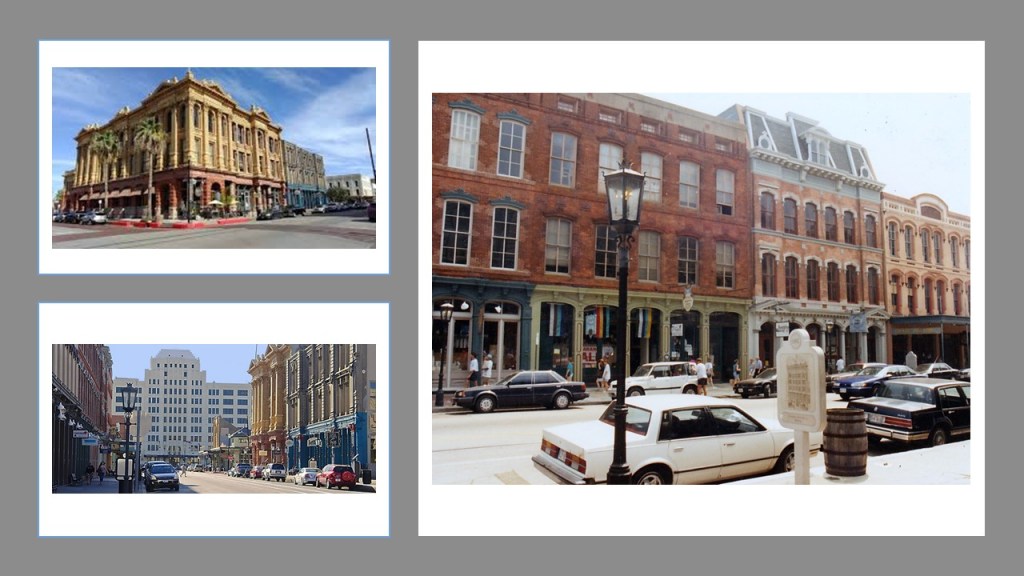

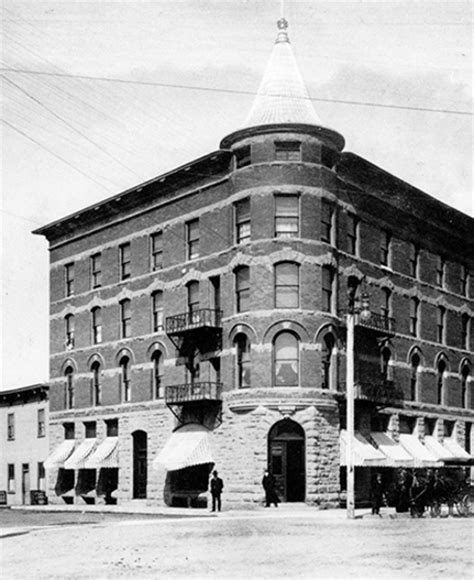

Galena is further upriver from Nauvoo in Illinois.

It is the largest city in, and county seat of, Jo Daviess County.

Charles Mound, called the highest natural point in the state of Illinois, is 11-miles, or 18-kilometers, northeast of Galena, in Jo Daviess County.

The city is named for the lead ore Galena, which formed the basis for the region’s early mining economy.

Galena was the location of the first big mineral rush in the U. S.

By 1828, Galena’s population of 10,000 was said to rival Chicago at the time, and it developed into the largest steamboat hub on the Mississippi River north of St. Louis.

The Galena Historic District is listed on the National Register of Historic Places…

…and it immediately reminded me of Portland, Maine…

…Edinburgh, Scotland…

…the Casbah in Old Algiers in Algeria.

…Old Zagreb in Croatia…

…and Ellicott City outside of Baltimore, Maryland.

Dubuque, Iowa is located at the junction of the states of Iowa, Illinois, and Wisconsin, in a region known as the Tri-State Area.

We are told the first permanent European settler here was a French-Canadian by the name of Julien Dubuque, who arrived in 1785.

In 1788, he received permission from the Spanish government, who controlled the Louisiana Territory to the west of the Mississippi River at the time, and the Meskwaki, also known as Fox ,tribe to mine the area’s rich lead deposits.

The Julien Dubuque Monument, located in Dubuque’s Mines of Spain Recreation Area, was said to have been constructed in the Late Gothic Revival style in 1897 at his grave-site.

The Mines of Spain Recreation Area has a network of trails to choose from.

This is the recreation area’s Horseshoe Bluff.

If there weren’t supposed have been any glaciers freezing and thawing over-and-over-again in the Driftless Region, what is the explanation for the existence of this wall-like-looking rock formation with the Mississippi River on top of it?

And why are there large cut-and-shaped stones seen around a parking area for Horseshoe Bluff on a street-view from Google Earth?

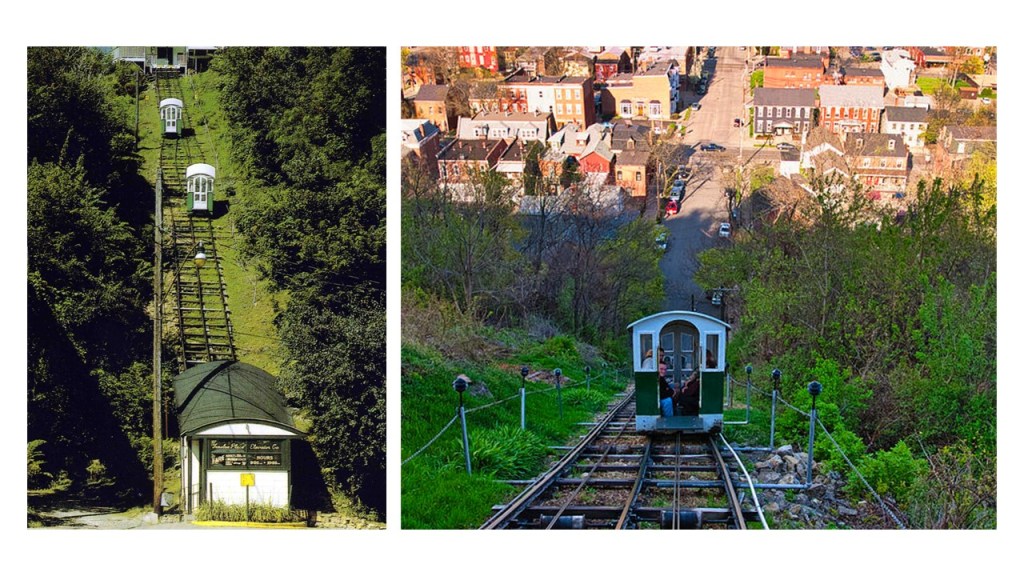

Elsewhere in Dubuque, the Fenelon Place Cable Car is found in the Cathedral Historic District, described as the world’s steepest, shortest scenic railway, said to have been built in 1882 for the private-use of J. K. Graves, a local banker and State Senator.

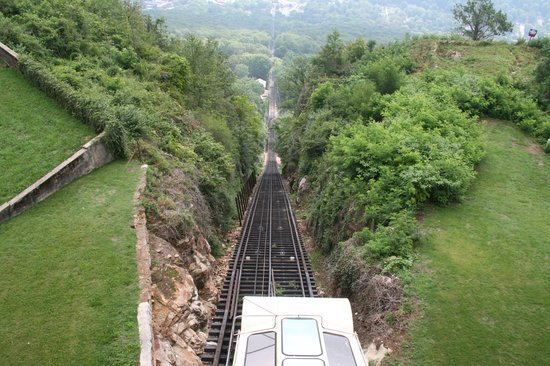

It is a funicular, also known as incline, railway, a transportation system that uses cable-driven cars to connect points along a steep incline, using two counterbalanced cars connected to opposite ends of the same cable, and found in diverse places like Look-out Mountain Incline Railway in Chattanooga Tennessee, said to have been constructed in 1895…

…the Budapest Castle Hill Funicular in Hungary, said to have opened in 1870…

…the East Hill Cliff Railway in Hastings, England, said to have opened in 1902…

…and two operating funiculars in Pittsburgh, the Duquesne Incline, said to have been completed in 1877…

…and the Monongahela Incline, said to have opened in 1870.

A couple of more things back in Dubuque before moving along.

The Dubuque Star Brewery was established by Joseph Rhomberg in 1898, which became one of the largest businesses of its kind in Iowa.

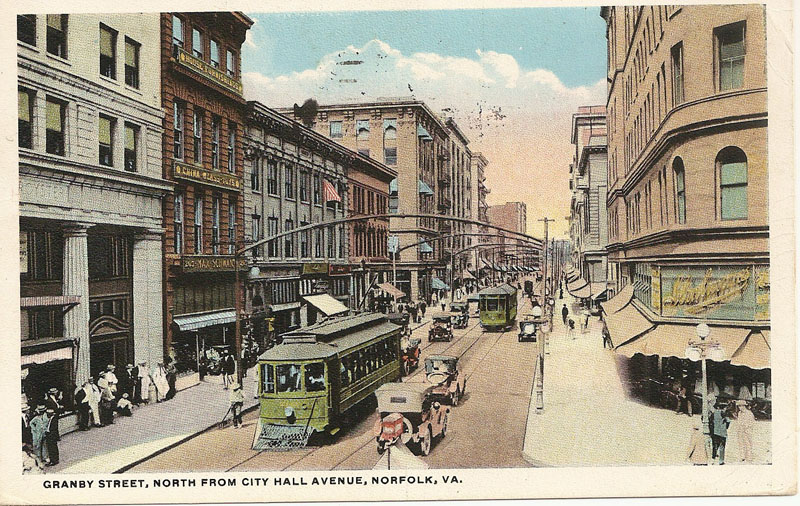

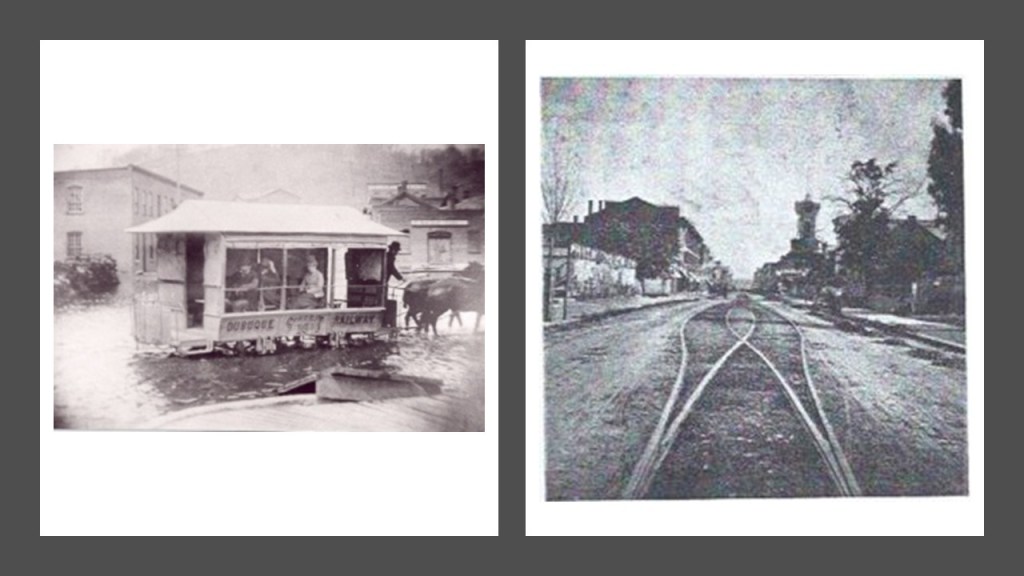

Starting in 1885, Joseph Rhomberg was also the General Manager and Superintendant of the Dubuque Street Railway Company, which at that time was still powered by horses as streetcar service had started there in 1868.

Electrification of the streetcar system in Dubuque came in sometime around 1892, and the system was only in use until 1932.

Dubuque’s North End was first settled by working-class German immigrants in the late-19th-century…

…and the South End of Dubuque was settled by working-class Irish immigrants.

Pike’s Peak State Park is upriver from Dubuque, and features a 500-foot, or 105-meter bluff located at the confluence of the Upper Mississippi and the Wisconsin Rivers.

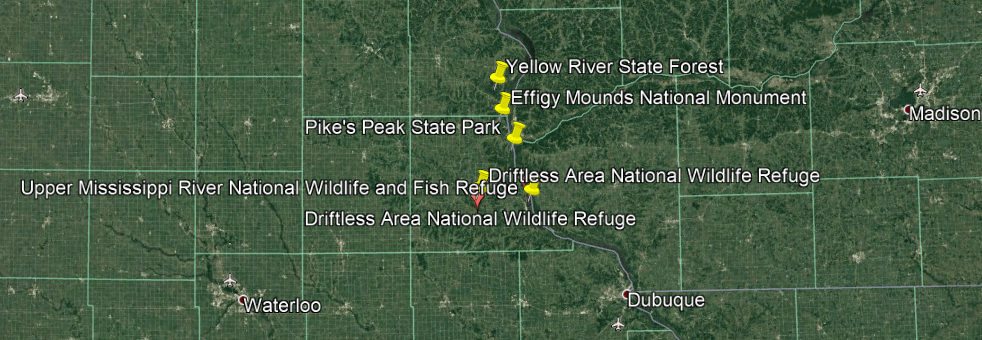

Pike’s Peak State Park is part of a larger system of Parks that includes the Effigy Mounds National Monument; the Yellow River State Forest; the Upper Mississippi River National Wildlife and Fish Refuge; and the Driftless Area National Wildlife Refuge.

The Effigy Mounds National Monument has more than 200 mounds, of which many are animal effigies, which we are told a hunter-gatherer culture built for unknown reasons.

The Yellow River State Forest is just north of the Effigy Mounds National Monument, and was said to have been established by the Civilian Conservation Corps in 1933, one of the New Deal programs established by President Franklin Roosevelt during the Great Depression.

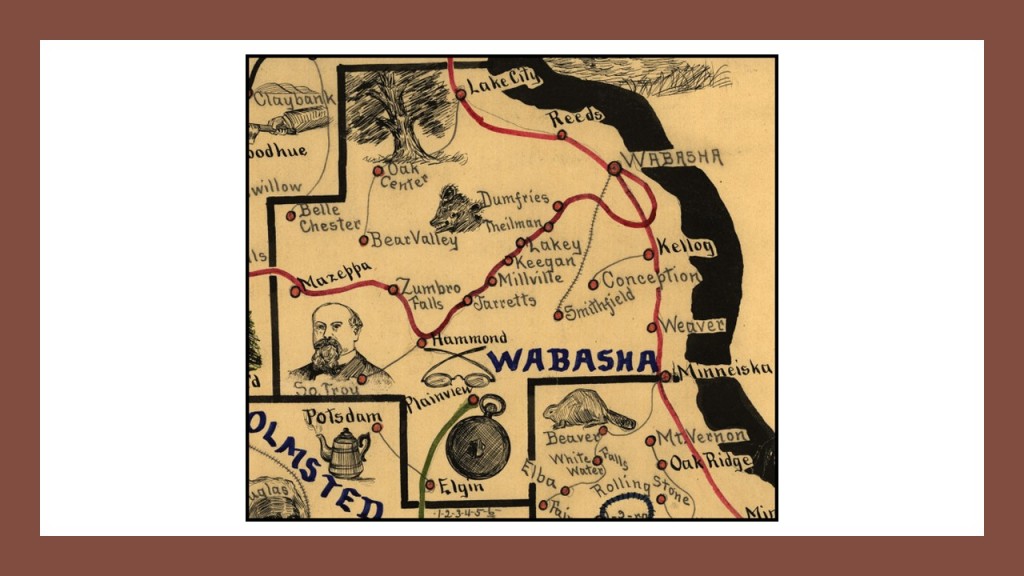

The Upper Mississippi River National Wildlife and Fish Refuge is one of only two in the United States the spans parts of four states – Minnesota, Wisconsin, Illinois, and Iowa, all the states of the Driftless Area – running from Wabasha, Minnesota to Rock Island in Illinois.

These land-forms are found in the Upper Mississippi River National Wildlife and Fish Refuge.

In the historical narrative we have been given, we are clearly told there were not glaciers here during the last Ice Age, a typical explanation for features in the landscape.

Then…how might these have been created?

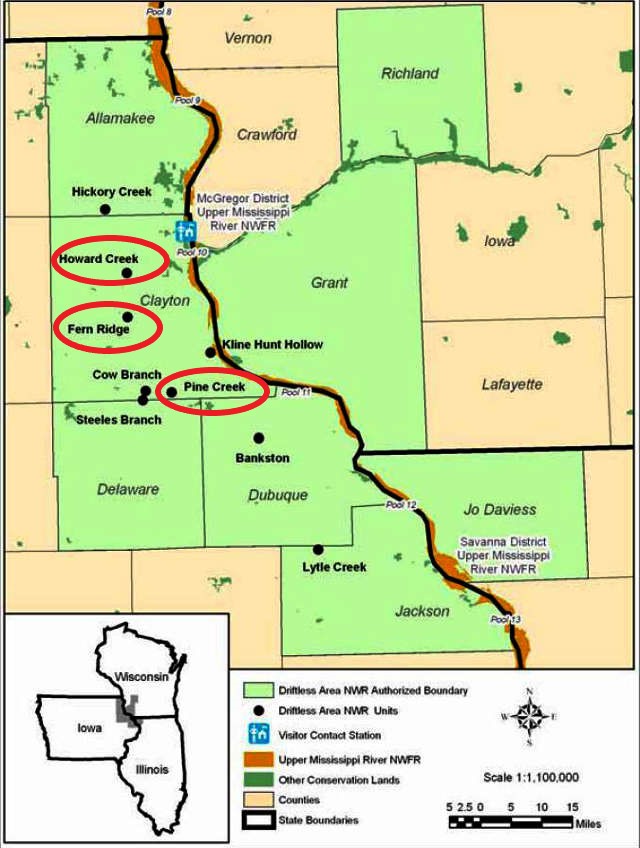

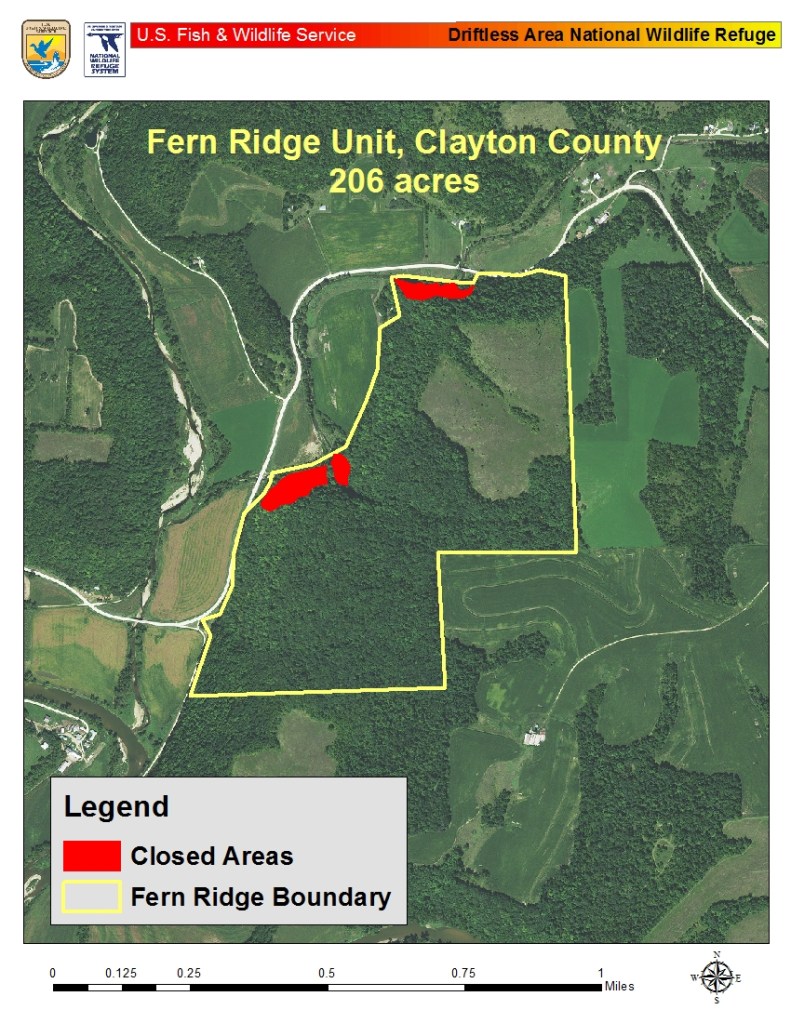

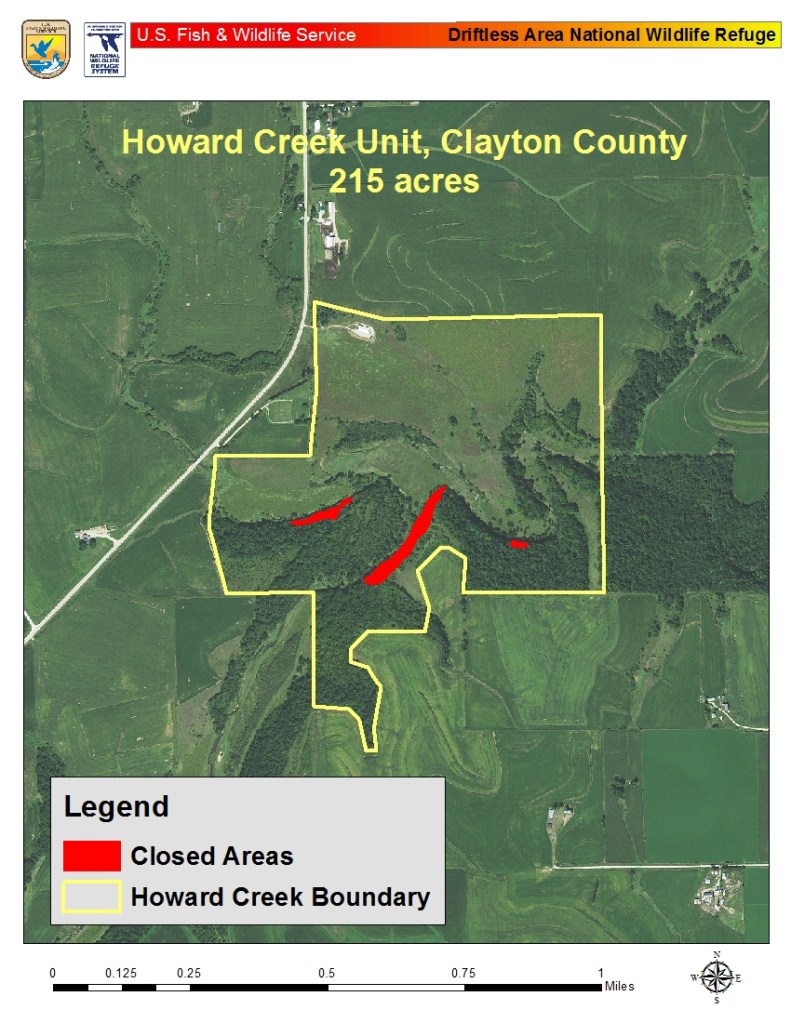

The Driftless Area National Wildlife Refuge is in both Iowa and Wisconsin, and there are only three units open for public use: Fern Ridge; Howard Creek; and Pine Creek.

Makes me wonder why they would limit the public’s access here.

There are even closed areas within the units open to the public.

Let’s take a look-see at the Driftless Area National Wildlife Refuge. Not finding a lot of pictures taken there, but here is one that was clearly marked as such.

The cities of McGregor and Marquette in Iowa and across the Mississippi River in Prairie du Chien, Wisconsin, are nestled between these parks.

Alexander McGregor established a ferry-landing in what became known as McGregor in 1837 after the end of the Blackhawk War in 1832, and the United States government opened up the expansion of land west of the Mississippi for settlement.

The City of McGregor was incorporated in 1857.

McGregor quickly became a commercial hub, after the Milwaukee and Mississippi Railroad finished the railroad track for a line running from Milwaukee to Prairie du Chien in 1857, and grain from Iowa and Minnesota was transported across the river for to send by railroad to Milwaukee.

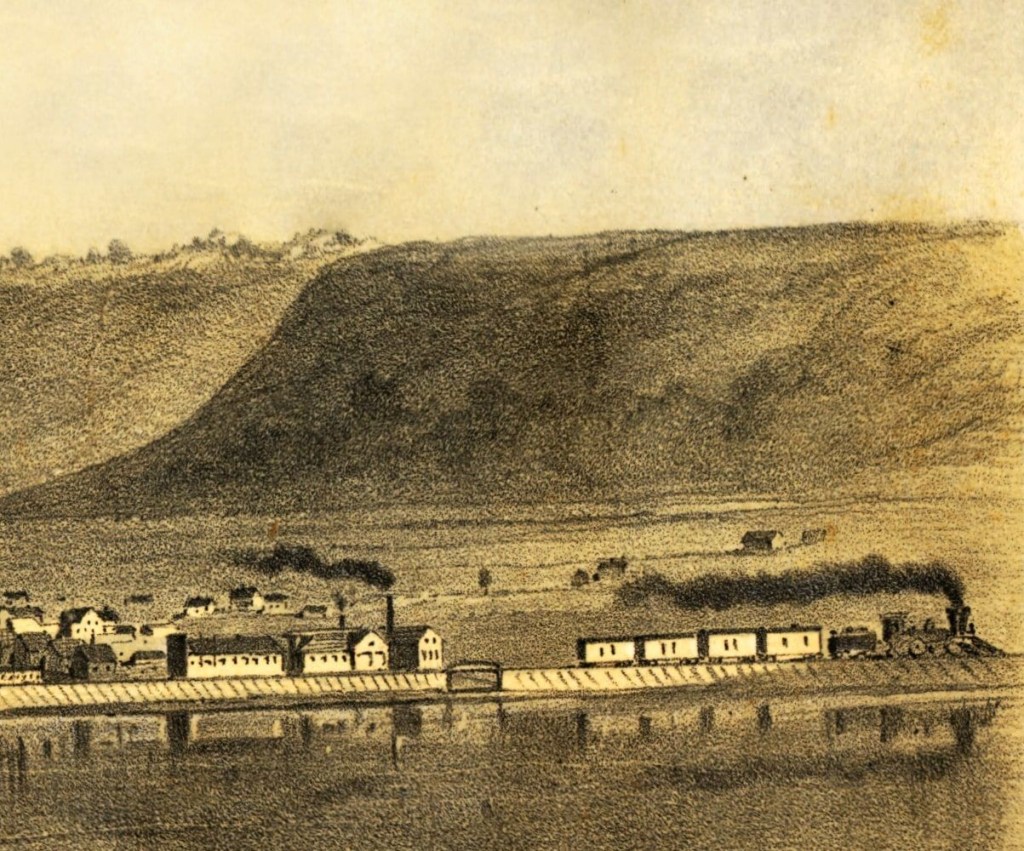

This photo is notated as McGregor in the mid-1860s.

We are told more railroads were built to connect McGregor with cities further west.

This hand-drawn map illustrated what appears to be the explosive growth of McGregor circa 1869.

The Lewis Hotel was said to have been built starting in 1899, with the lead architect being the Austrian-born Hugo Schick of Schick & Roth, based out of LaCrosse, Wisconsin.

The Lewis Hotel still stands today, only it’s now called the Alexander Hotel, minus the domes it had originally.

More on LaCrosse shortly.

I found this interesting-looking historical picture of McGregor with the Lewis Hotel seen in it.

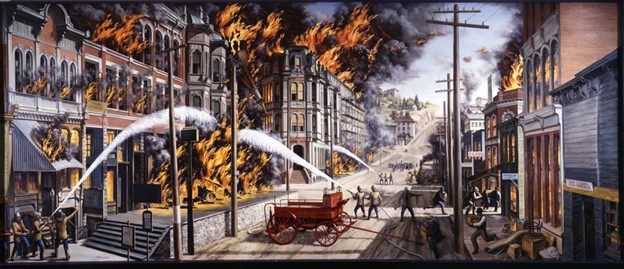

Apparently the destruction pictured here in McGregor was the result of an electrical storm in which lightening caused a fire, and the same storm produced a heavy-downpour, causing a flood of mud and water, on May 19th of 1902.

Here is an historic photograph of MacGregor’s Main Street…

…and Main Street today.

Marquette, Iowa, is located just a short-distance north of McGregor, and across the river from Prairie du Chien in Wisconsin.

Named for the Jesuit Jacques Marquette, who along with Louis Joliet, was said to have discovered the Mississippi River through here in 1673, it was originally incorporated as North McGregor in 1874.

It served as a railroad terminus for McGregor.

The Riverboat Casino Queen is a popular attraction in Marquette, and I can’t help but notice the distinctive conical shape it sits right next to it.

Marquette is connected to Prairie du Chien via the Marquette-Joliet Bridge, taking U. S. Route 18 from Iowa to Wisconsin.

Prairie du Chien was established in the late 17th-century…

…by French Voyageurs, French Canadians who transported furs by canoes during the fur trade years between the early-17th-century and mid-19th-century.

A fur-trading post was established in the area in 1685 by Nicholas Perrot.

Then in the 19th-century, German-immigrant John Jacob Astor, the first prominent member of the Astor family and America’s first multi-millionaire, established the Astor Fur Warehouse, said to have been built in 1828, and was an important place for the regional fur trade for which Astor established a monopoly out west.

The Astor Fur Warehouse has a mud-flooded appearance with the ground-level window, and the below-ground-level entranceway.

During the 19th-century, Fort Crawford was an outpost of the U. S. Army at Prairie du Chien.

The first Fort Crawford was said to have been occupied between 1816 and 1832…

…and the second was occupied between 1832 and 1856, and has been preserved as the Fort Crawford Museum in what was the Fort’s military hospital.

Fort Crawford was said to have been part of a series of fortications along the Upper Mississippi River that included Fort Snelling, located in Minnesota near St. Anthony Falls, with its construction said to have been completed in 1825…

…and Fort Armstrong, in Rock Island, Illinois, said to have been constructed between 1816 and 1817.

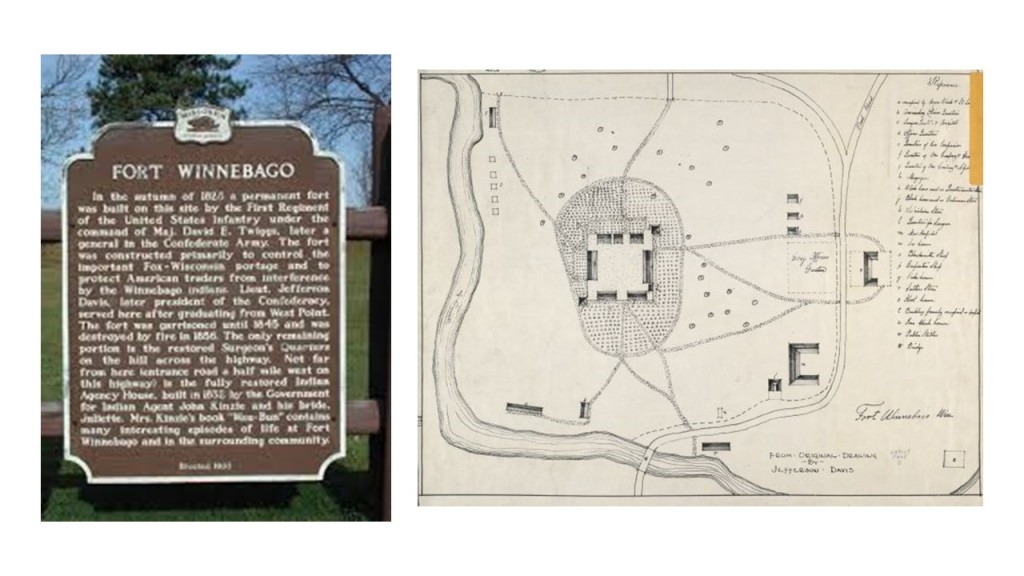

…and Fort Crawford was part of a string of forts in the Fox-Wisconsin Waterway, which included Fort Howard, near the mouth of the Fox River in Green Bay, and said to have been the first fortification built in what became Wisconsin…

…and Fort Winnebago in what is now Portage, Wisconsin, and said to have been constructed in 1828.

The next place we come to heading north on the Mississippi River is LaCrosse, Wisconsin, the largest city on Wisconsin’s western border.

A regional hub, companies based in LaCrosse include:

Kwik Trip, a family-owned chain of convenience stores founded in 1965…

…City Brewing Company, established in 1999…

…after investors purchased the former brewery buildings belonging to the G. Heileman Brewing Company which had been originally founded in 1858 by two German immigrants – Gottlieb Heileman and John Gund.

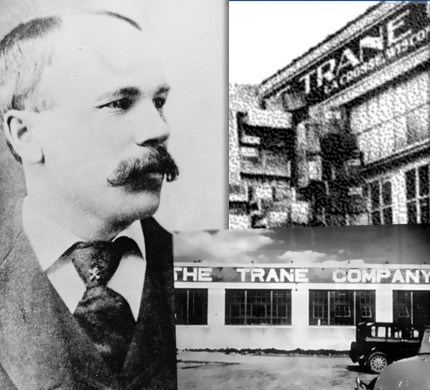

…and Trane is based in LaCrosse, a manufacturing company of HVAC systems and building management systems and controls…

…the origins of which apparently date back to 1885, when an immigrant from Tromso, Norway, James Trane, first established a plumbing and pipe-fitting shop in LaCrosse.

The Losey Memorial Arch at the entrance of LaCrosse’s Oak Grove Cemetery was said to have been designed by the same architectural firm responsible for designing the Lewis Hotel back in McGregor, Schick and Roth, and built in 1901.

Schick and Roth are also given the credit for designing other buildings in LaCrosse, including the:

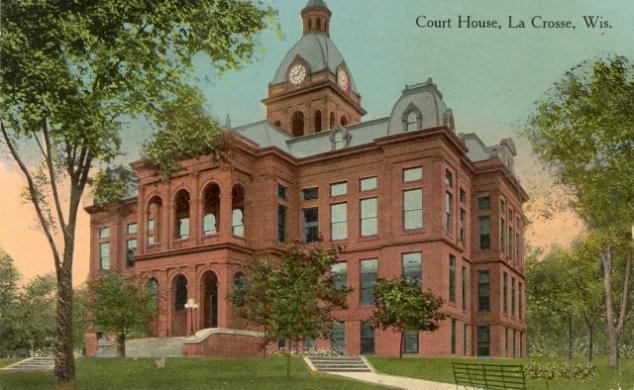

The old County Courthouse in 1904…

…and the Holway House 1892, now the Castle LaCrosse Bed & Breakfast.

LaCrosse is surrounded by bluff-lands, towering around 500-feet, or 150-meters over an otherwise flat plain.

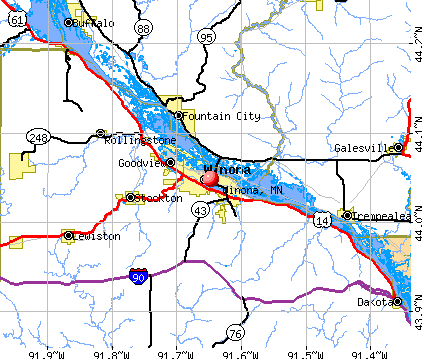

The next place I am going to look at is Winona in Minnesota…

…in the Mississippi River Bluff Country.

It has a notable landscape feature is called “Sugar Loaf,” described as a rock pinnacle that was created by quarrying in the 19th-century, towering over Lake Winona.

Sugar Loaf in Winona reminds me of Chimney Rock in Sedona, where I live and see it every day.

Lake Winona has a really massive band-shell…

…which we are told was dedicated as a new structure in June of 1924.

Europeans arrived to settle Winona in 1851, laying out the town in lots in 1852 and 1853.

The first settlers were said to have been Yankees from New England, and then in 1856 German immigrants arrived to settle the area, and later immigrants from Poland.

…with the construction of the Winona-St. Peter Railroad from Winona to Stockton, Minnesota, being completed in 1862, which would have been during the American Civil War.

Wabasha, Minnesota is my next stop.

It was founded in 1830, and apparently wants the world to know, and only know, it was the setting for the 1993 movie “Grumpy Old Men.”

The only thing that I remember about “Grumpy Old Men”…

…is that there was ice-fishing in it.

That’s about all I remember from it!

What else comes up for Wabasha?

This is what we are told.

Wabasha was first settled by Europeans in 1826, and is Minnesota’s oldest city and longest continually inhabited River town.

It was recognized as a city in 1830, when Chief Wabasha II of the Mdewakanton Dakota Sioux tribe, and representatives of other tribes of the region, signed the Treaty of Prairie du Chien in 1830, ceding territory to the United States.

Then Chief Wabasha III, signed the 1851 and 1858 treaties that ceded the southern half of what is now the State of Minnesota to the United States, beginning the removal of his tribe to several reservations further and further away from Minnesota, ending up at the Santee Reservation in Nebraska, where Chief Wabasha III died.

In the 1830s, Augustin Rocque established a fur trading post there, and the community grew around his trading post, with the city being platted in 1854 and incorporated in 1858.

Wabasha became a bustling town, with industries like trading, clamming, factories, shipping, and flour-milling, and it became a rail transportation hub in 1857, with three railroads intersecting here – the Minneapolis, St. Paul & Chicago Railroad; the Minnesota Midland Railroad; and the Lake Superior & Chippewa Valley Railroad.

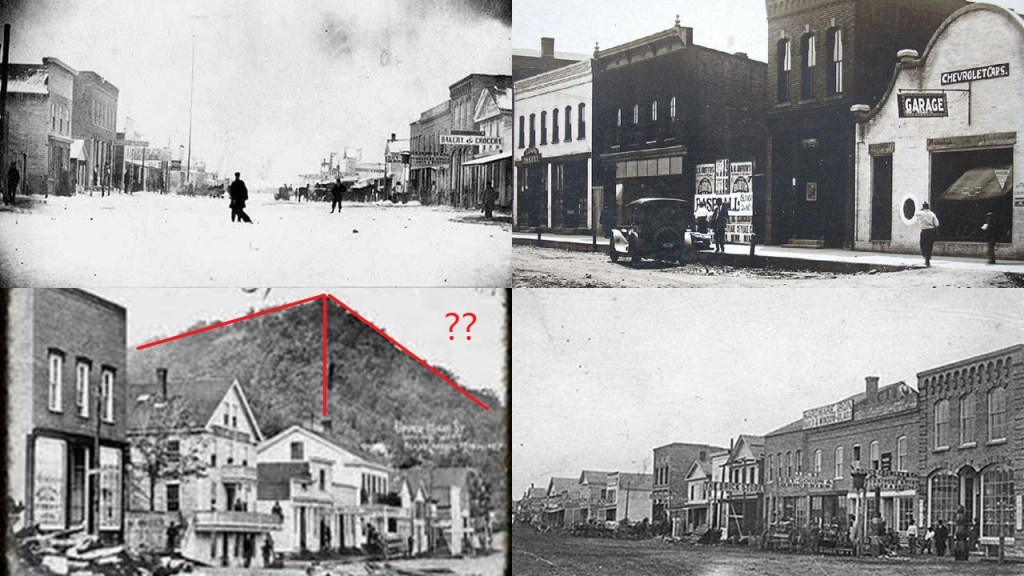

Here are some historic photos of Wabasha, with nice masonry buildings, dirt-covered streets, not very many people, and possibly a pyramidal-shape in the background in the lower-left photo.

And here is downtown Wabasha today.

The last place I want to look for the purposes of the post on the Driftless Region is Red Wing, Minnesota.

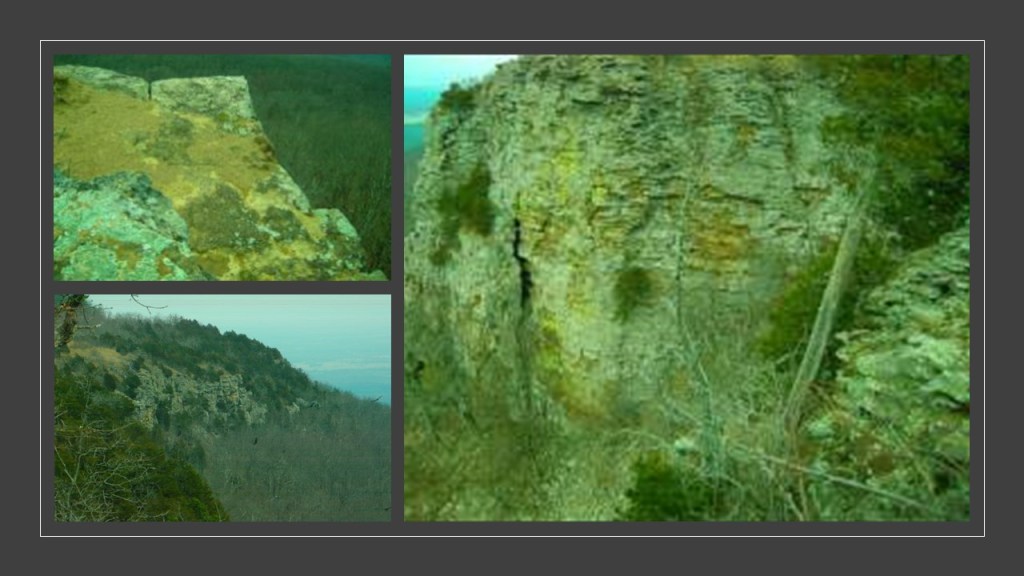

Trails from Red Wing lead up to the massive landmark above the city known as Barn Bluff.

I have to say that one of my first a-ha’s in this journey of waking up to the ancient civilization in the environment around me was realizing the code of how they managed to cover it up by calling everything natural, and leaving it out of our historical narrative.

The light-bulb about this came on for me when I visited Mt. Magazine in Arkansas several years ago where “Cameron’s Bluff” is located.

Cameron’s Bluff is such an ancient wall that there is some element of doubt.

But there are some places you can really tell it is a built structure.

I took these photos of Cameron’s Bluff in Arkansas.

I think the definition of bluff meaning high cliff is actually a bluff, meaning an attempt to deceive someone.

Bluffs, canyons, mesas and the like are actually really ancient infrastructure.

The St. James Hotel in Red Wing is described as Italianate architecture that was built between 1874 and 1875, the year that it opened for business as…

…one of the most elaborate hotels on the Mississippi River.

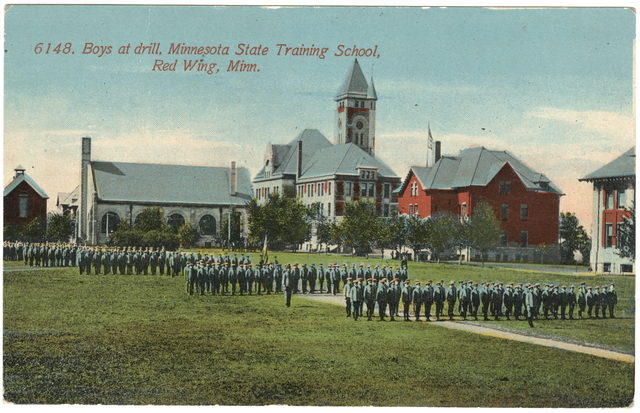

The Minnesota Correctional Facility in Red Wing, said to have been constructed in 1889…

…used to be known as the Minnesota State Training School once-upon-a-time.

And, in case you are wondering, Red Wing, Minnesota, is the home of the Red Wing Company, Museum and Store, where you can find the perfect shoe for the giant in your life.

Again, I really appreciate everyone’s suggestions, as I had a good list of places to look into in the Driftless Area.

I ended up sticking to places along the Mississippi River because that is the direction my research happened to unfold when I realized the Mississippi River runs through the heart of the Driftless Region.

I am noticing a recurring pattern coming up in my research, so my next blog post will be about German entrepreneurs and settlements in the Mississippi and Ohio River Valleys in the 19th-century.