I have been researching aspects of what I am presenting in this video for years, but this subject has come about as an in-depth research topic for me right now because Aaron, from the “Uncovering Hidden West Virginia” video presentation, suggested that I look into this particular topic.

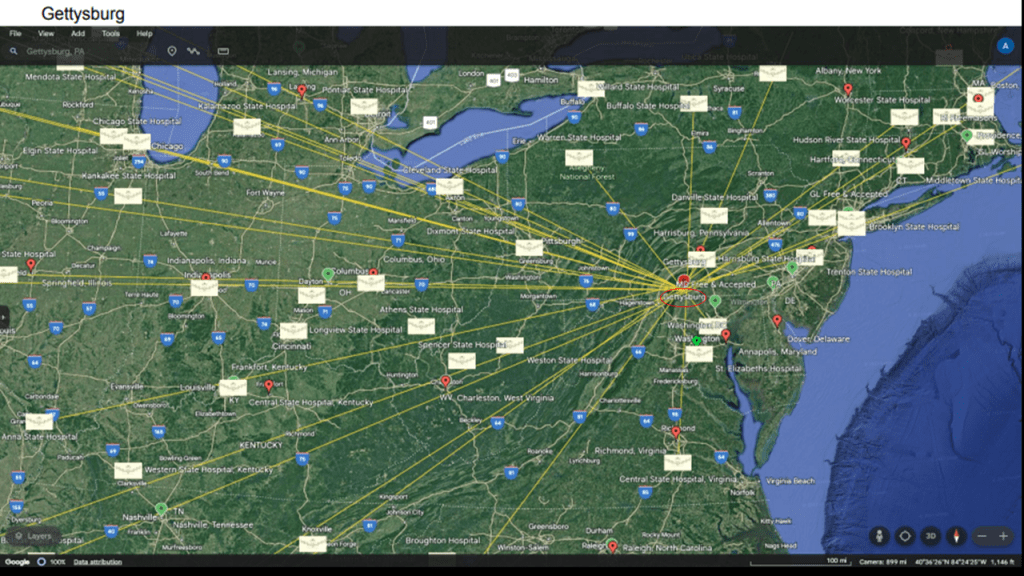

He sent me places he had identified to look at in Pennsylvania and West Virginia; different articles he found on giants skeletons; and some place alignments he discovered from his own inner prompting that is very revealing in terms of what has actually been going on here

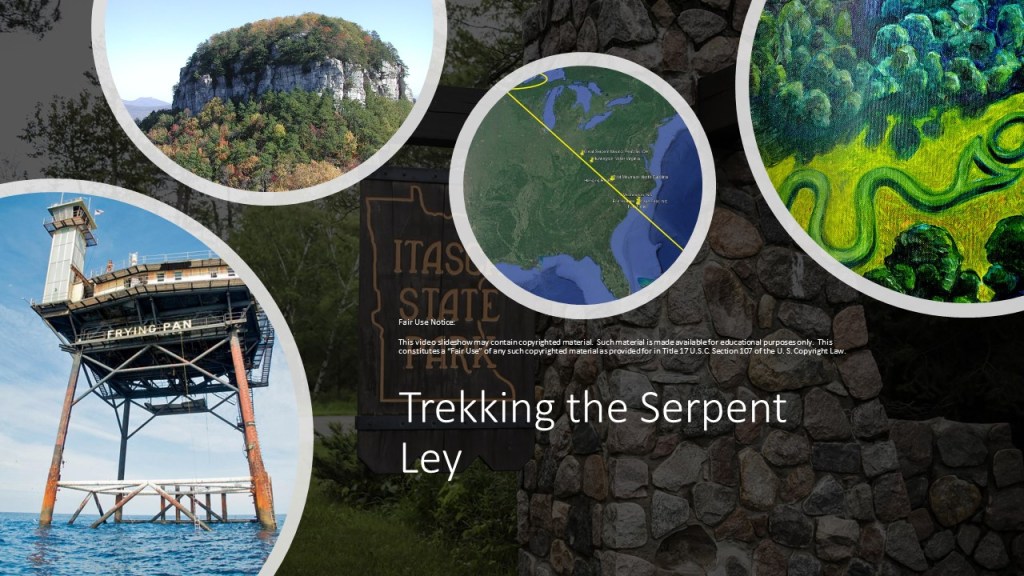

Aaron reached out to me after he watched my “Trekking the Serpent Ley” video from this past August, in which I brought up the subject of Appalachia, because the Serpent Ley crosses right through there.

This piqued his interest, because he doesn’t see Appalachia talked about very much, and believes it worthy of more attention. Especially after doing this deep dive, I wholeheartedly agree with him!

Aaron is deeply connected to Appalachia, having been born and raised in Marion County, West Virginia, and currently resides in Western Pennsylvania.

I grew up in suburban Maryland in a location very close to a lot of the places mentioned in this video, so I have been to, or near, many of the places mentioned here – church youth retreats, school trips, sightseeing trips, and many other occasions.

Growing up, we accepted as true what we are told about our history, but I know from my own experience of them that these places have a feeling of being much older beneath the surface of our awareness, just like the giants themselves.

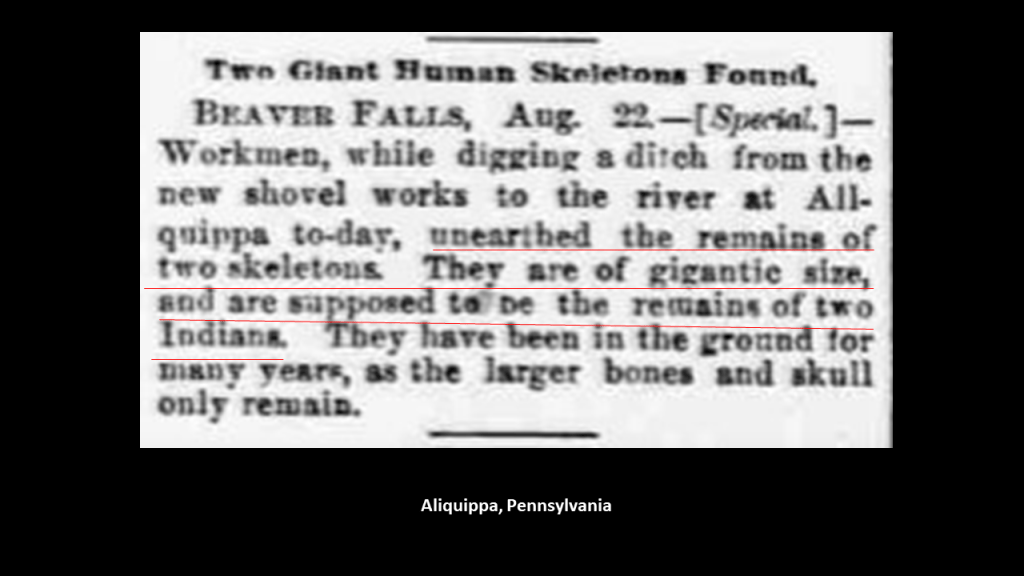

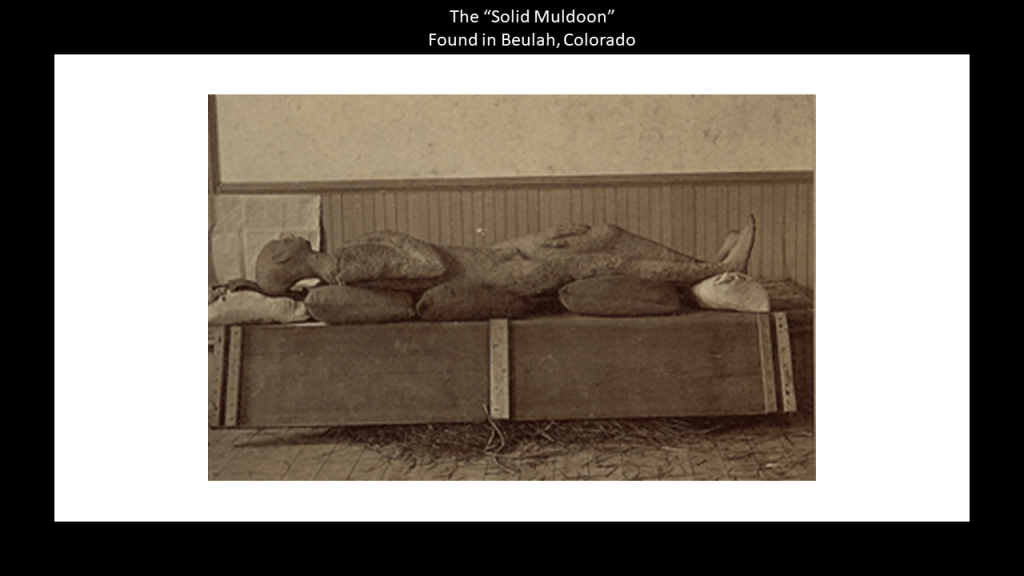

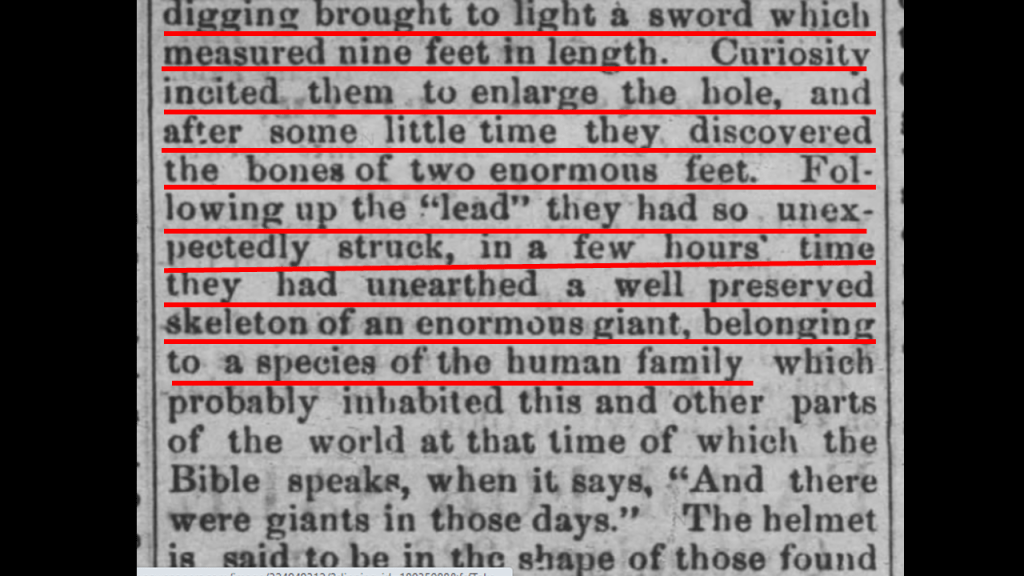

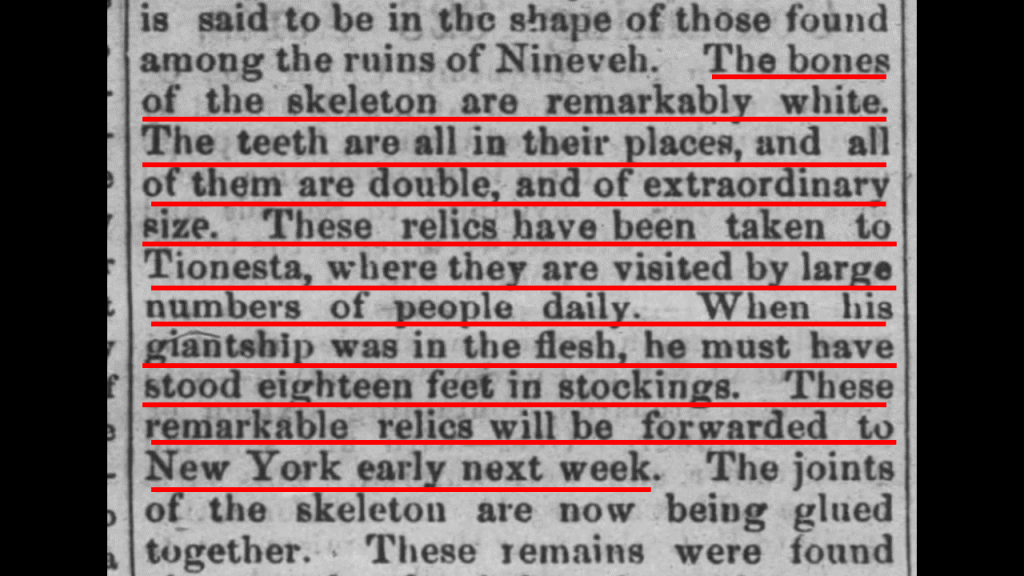

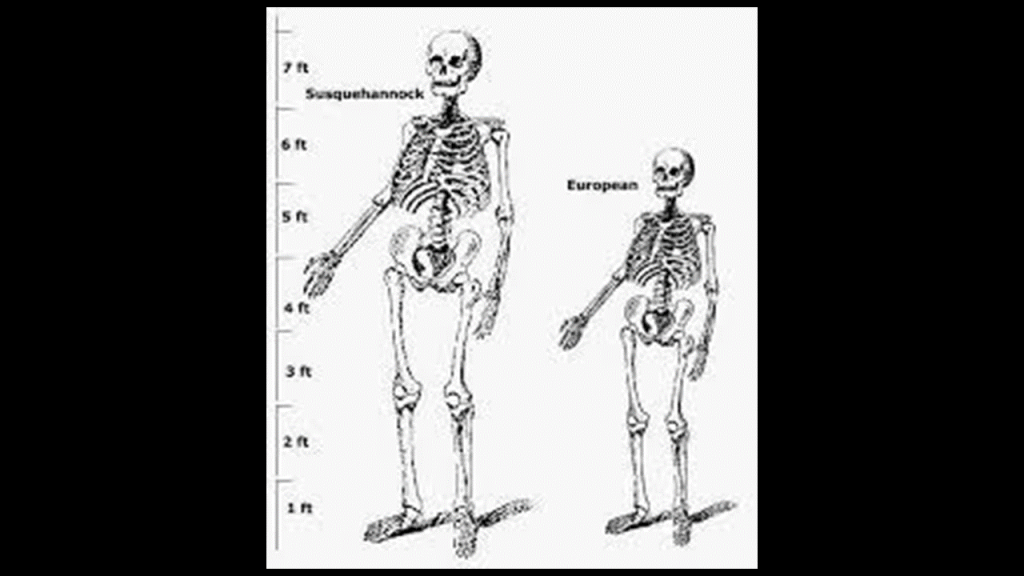

There is no question that the consistent finding of giant human remains was well-documented in the 19th-century, several examples of which are presented in this post, from skeletons that were reported to be found co-located with mounds, to skeletal remains found randomly from digging.

Today, the very existence of giants seems to be vigorously denied, and/or fact-checked as a hoax, when their remains turn-up somewhere these days.

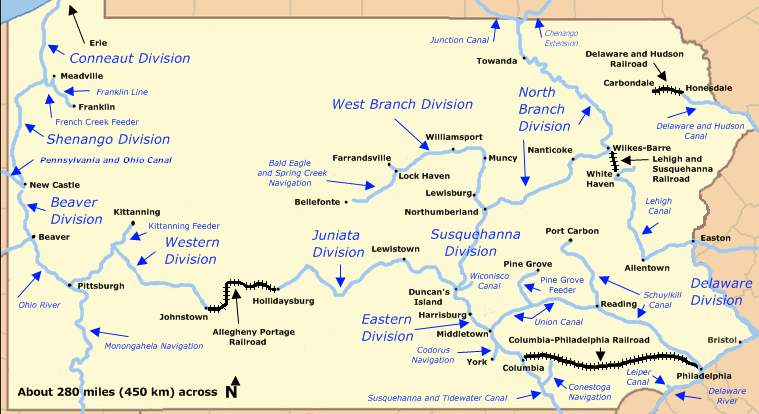

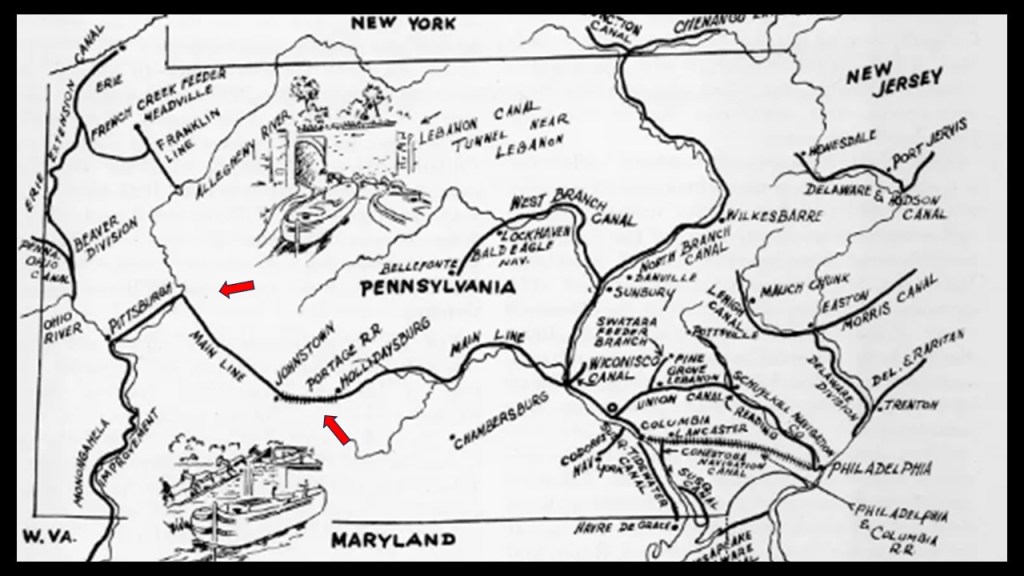

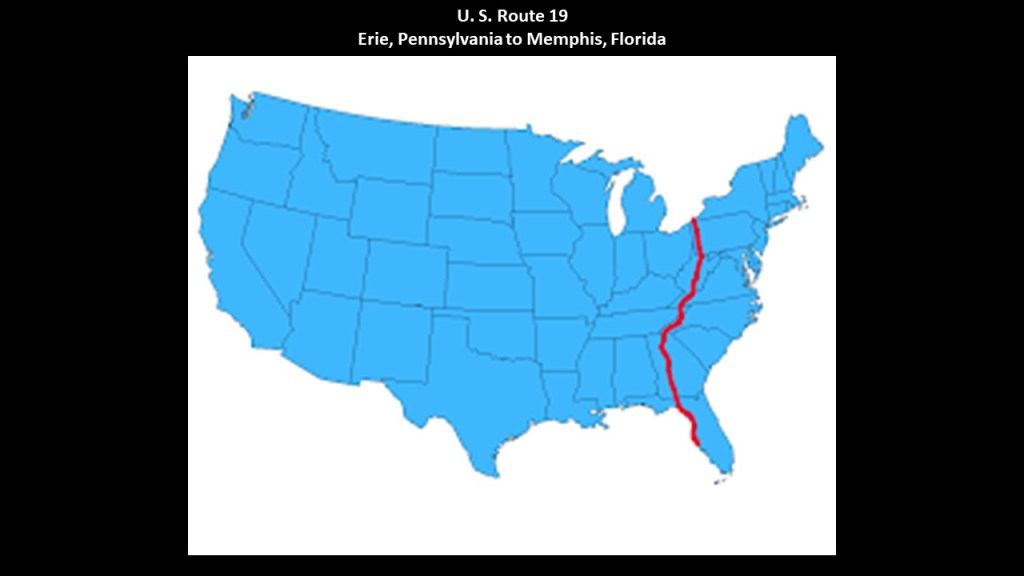

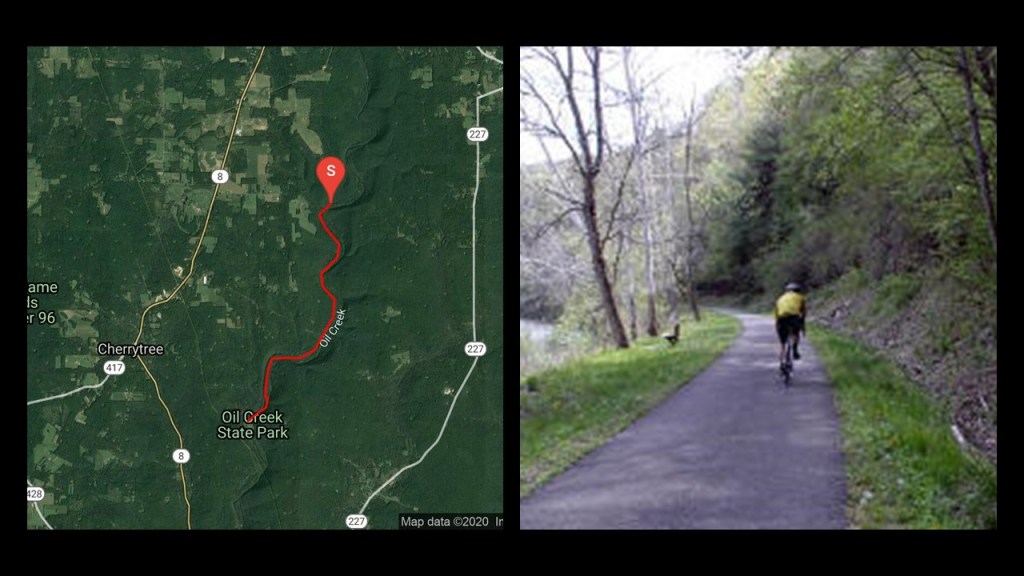

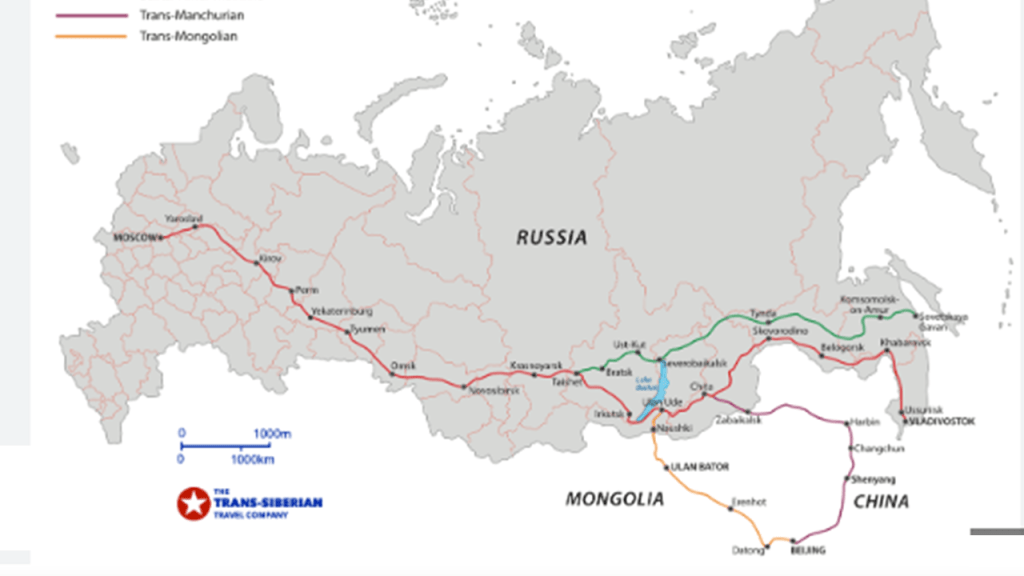

Then there are recurring themes that come up consistently throughout this video, including but not limited to, incredible feats of canal, railway, and tunnel-building that we are told began in our history around the late 1700s and early 1800s, most of which was completely obsolete by the early to mid-20th-century; S-shaped river bends and a history of railroads running alongside them throughout the region; mass clear-cutting of forests and mining coal-fields and iron-ore deposits until completely depleted, then the railroads started to disappear; and many of the former rail-beds having been turned into recreational trails.

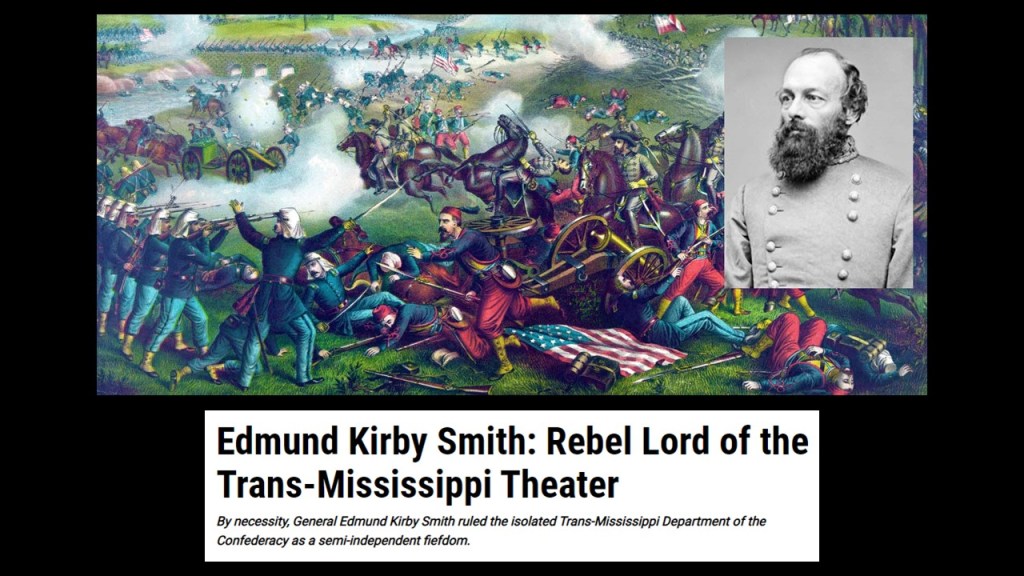

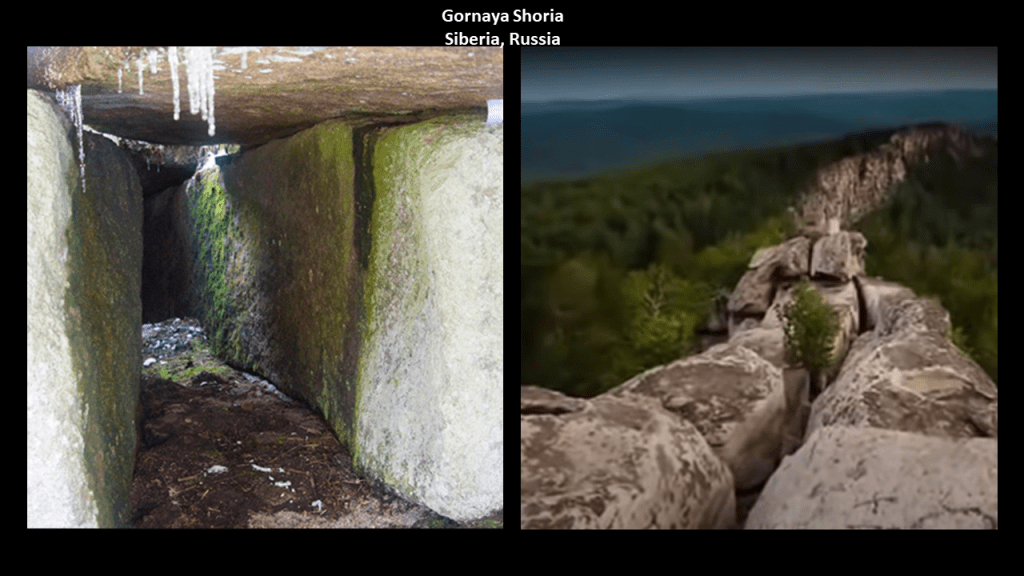

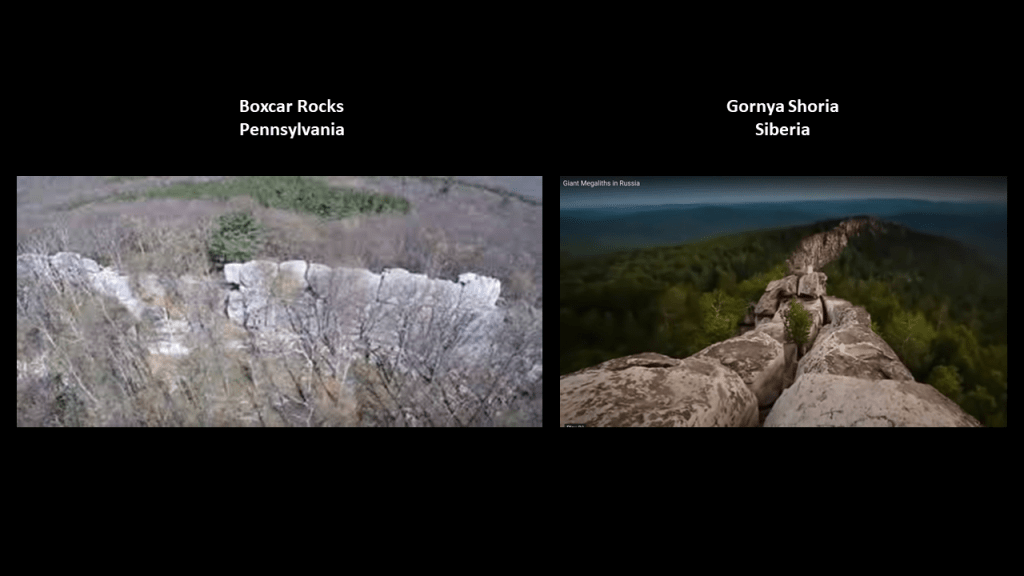

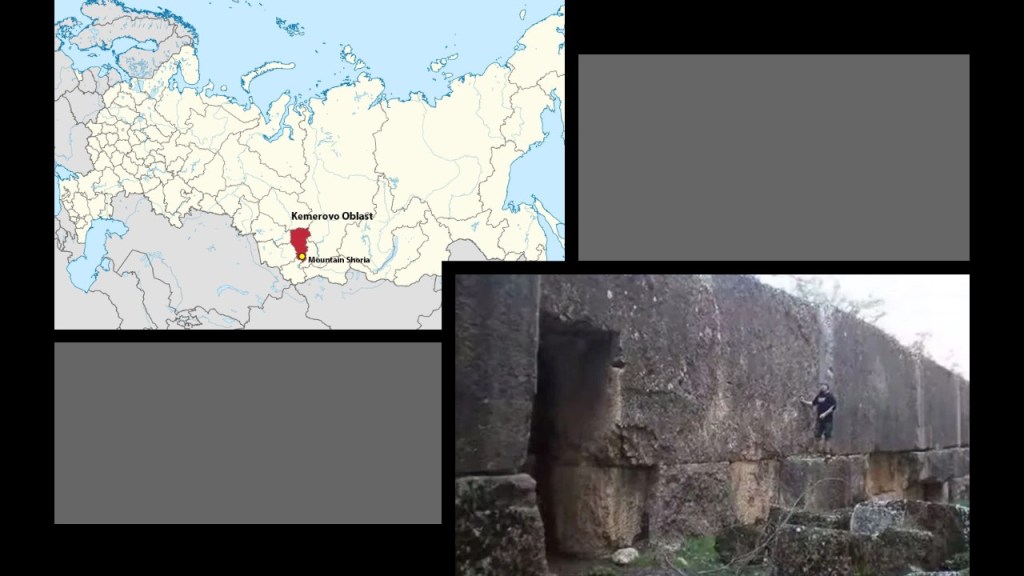

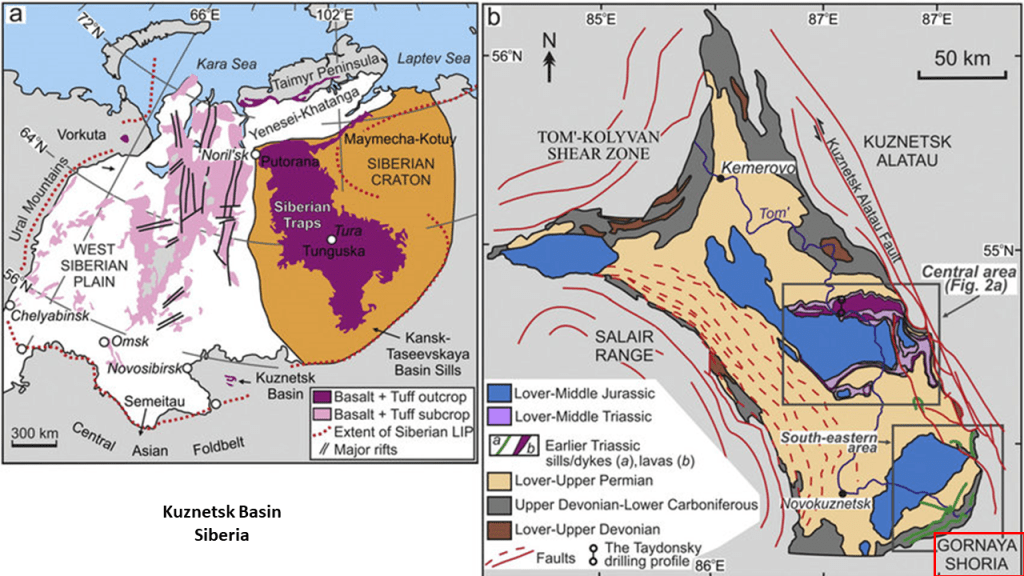

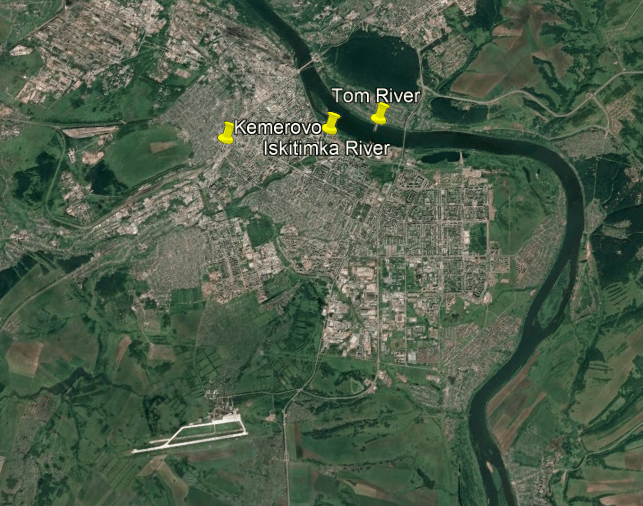

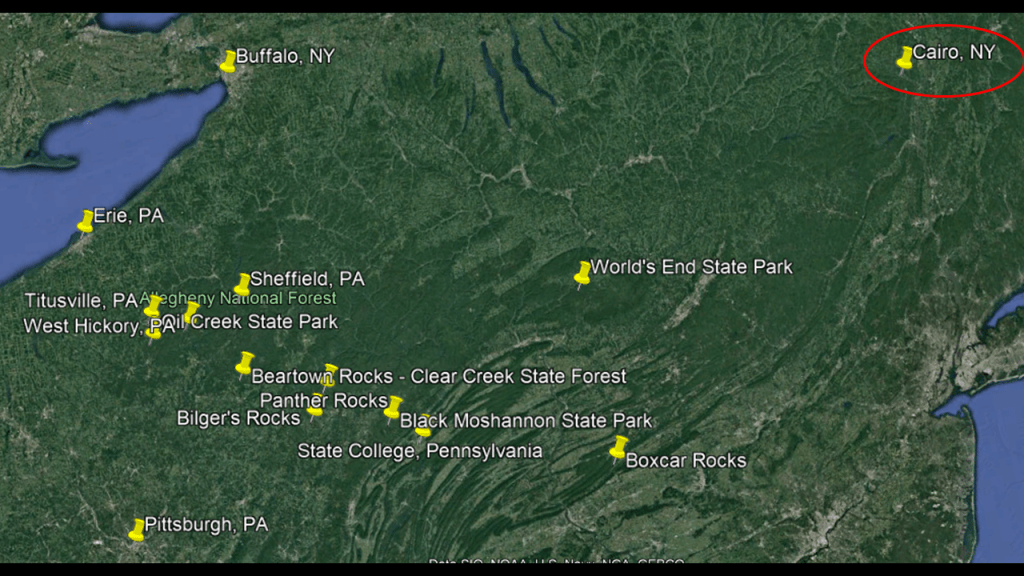

My primary focus was Appalachia in western Pennsylvania and eastern West Virginia, though I did look at other places as well, including the location of Gornaya Shoria in southern Siberia.

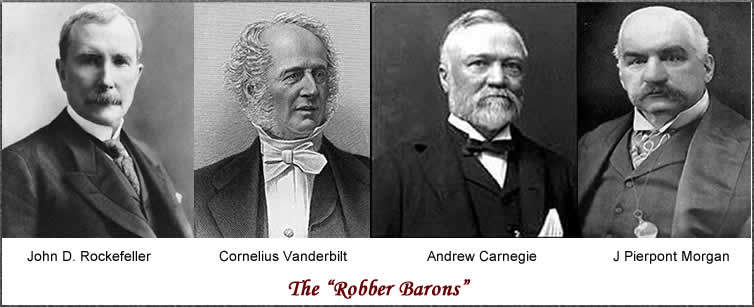

By the end of this video, you will see another story about what has actually taken place here coming into focus as I take a very close look at this region and its official history, which among other things, was important to the settlement and industrialization of America, and also the wealthy and influential men behind it all.

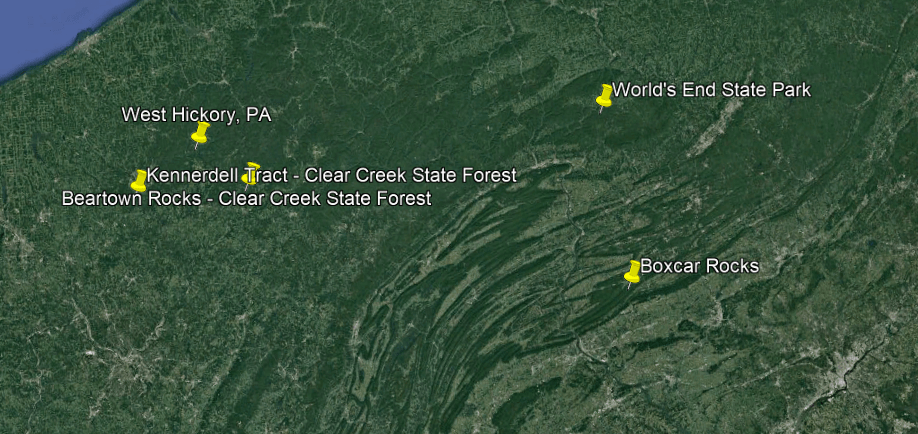

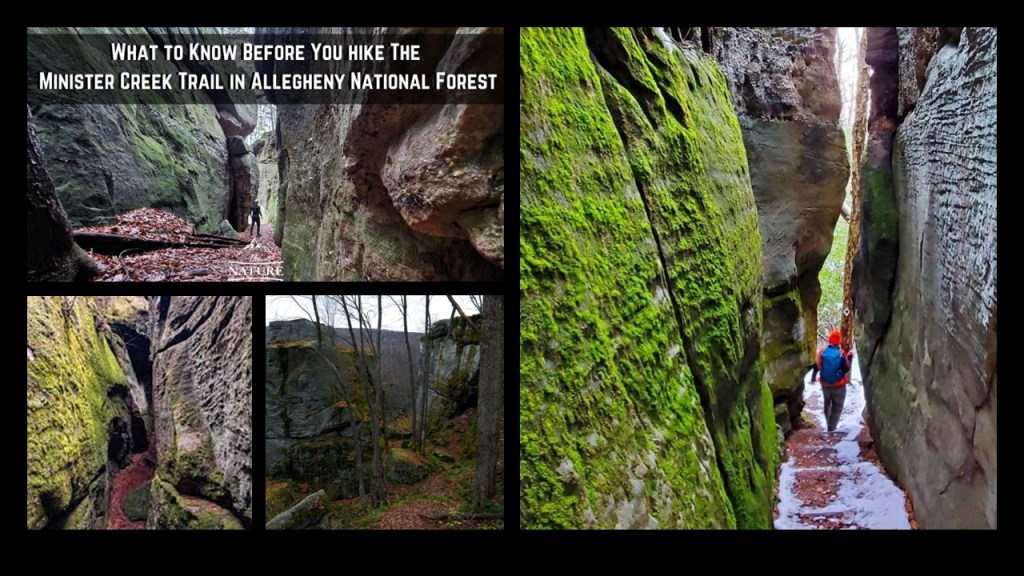

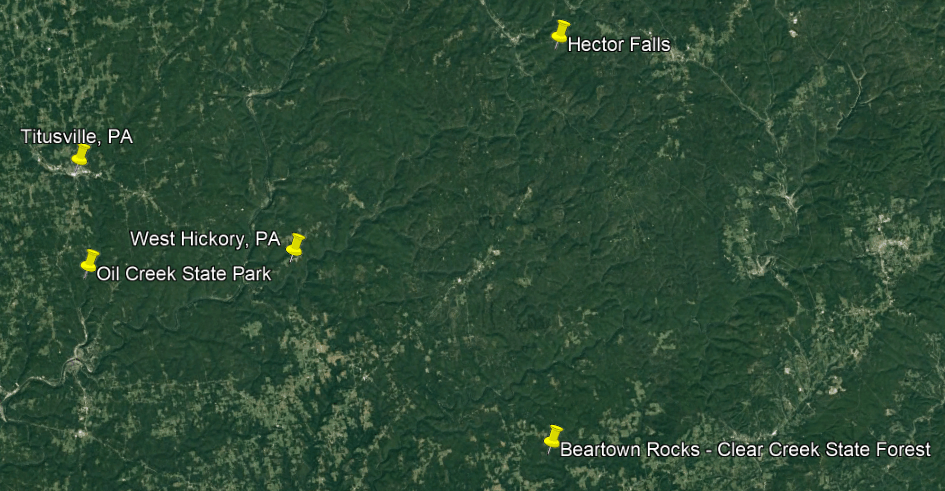

My starting point for the research in this post are places in Pennsylvania that Aaron sent me that he had identified as looking like megalithic stone structures

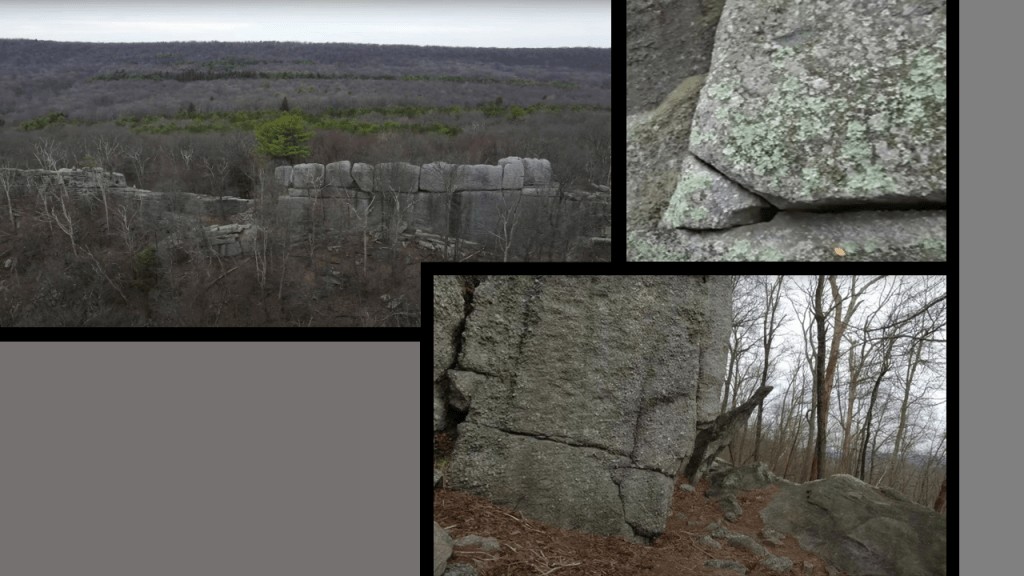

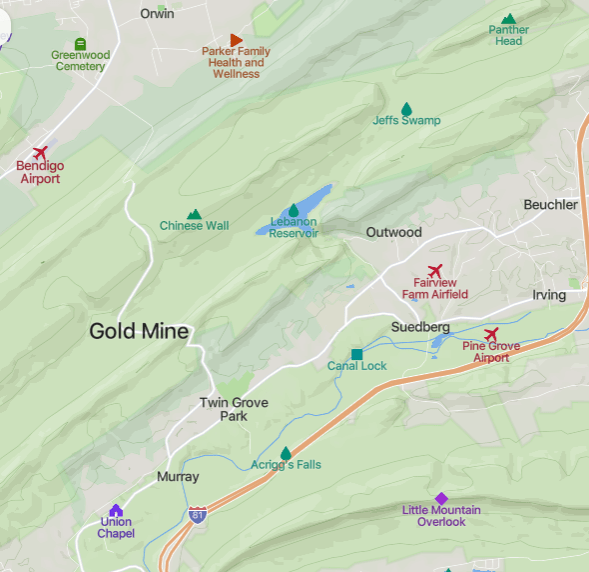

The first place that Aaron directed my attention to was the location of “Boxcar Rocks,” also known as the “Chinese Wall,” and the “High Rocks,” on Gold Mine Road in Lebanon County.

We are told that they are a natural geologic formation a little over a half-mile, or .8-kilometers, long, and 60-feet, or 18-meters, high.

They are described as a long line of stacked boulders that were likely left over from melting glacial deposits during the last Ice Age, though there is some disagreement on the issue of whether or not there were glaciers that far south in Pennsylvania.

Yet here are images that Aaron sent me where the stone blocks of Boxcar Rocks look like they have been cut-and-shaped!

Gold Mine is the name of a Hamlet in Cold Spring Township.

Cold Spring Township was incorporated in 1853.

In 2010, there was a population recorded of 52 people.

There is no local government here, nor services – no taxes, no water, no sewage, and no public officials.

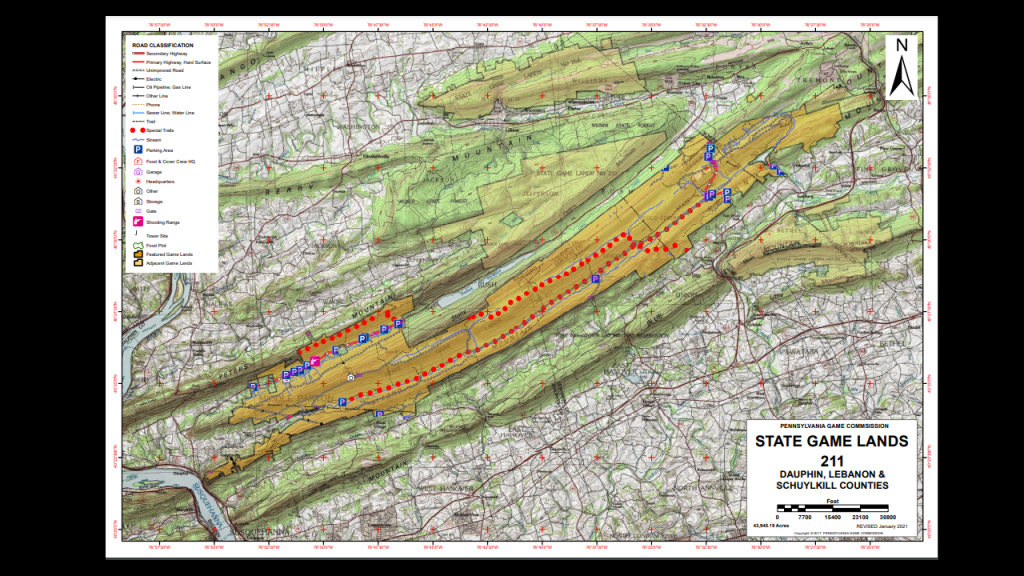

Most of the Township is part of “Pennsylvania State Game Lands #211,” who manage the lands for the purposes of hunting, trapping, and fishing.

The Appalachian Trail runs through “Pennsylvania State Game Lands #211” in Swatara State Park.

This is Lock #5 of the old Union Canal on the “Bear Hole Trail” of Swatara State Park.

This section of the Union Canal was said to have been closed after the dam holding the reservoir was washed away by a devastating flood in 1862, and the rest of the Union Canal was said to have been closed to use in 1885 because it could not compete with the “efficiency of the railroad.”

The 82-mile, or 132-kilometer, -long Union Canal in southeastern Pennsylvania between Middletown, Pennsylvania to Reading, Pennsylvania, was said to have been built between 1792 and 1828, until it closed in 1885.

We are told the American Canal Age was between 1790 and 1855, and started in Pennsylvania, where the first legislation surveying canals was passed in 1762.

The construction of the Union Canal was said to have started under the administration of President George Washington in 1792, and was touted as the “Golden Link” in providing an early transportation route for shipping anthracite coal and lumber to Philadelphia.

The “Main Line of Public Works,” of which the Union Canal was a part of, was passed by the Pennsylvania Legislature in 1826.

It funded various transportation systems, including canal, road, and railroad.

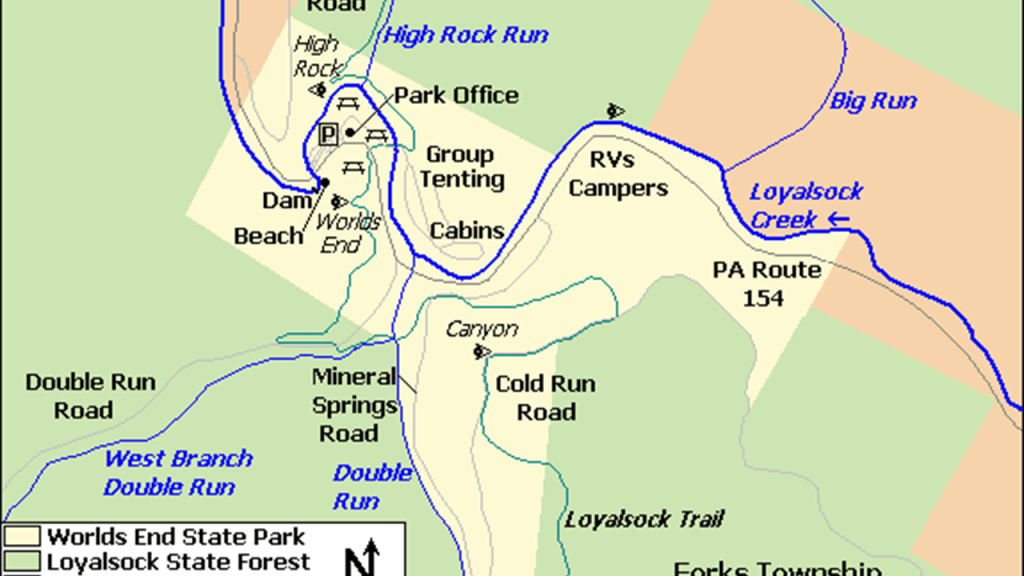

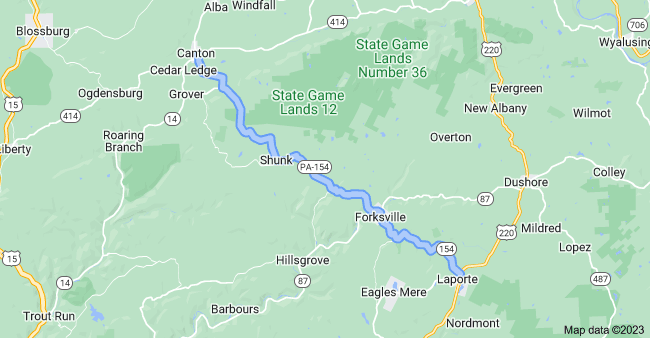

Next, Aaron drew my attention to the World’s End State Park is in Forksville, Pennsylvania, in the Loyalsock State Forest, and is situated around the s-shaped bends of Loyalsock Creek.

World’s End State Park is in Forksville, Pennsylvania, in the Loyalsock State Forest, and is situated around the s-shaped bends of Loyalsock Creek.

Forksville is a village of about 200 people that is almost encircled by park and the forest on Pennsylvania State Route 154.

Not much there, but it does have Victorian-style architecture and a covered bridge.

These locations are in Pennsylvania’s “Endless Mountains,” a region of northeastern Pennsylvania that are not considered true mountains, but a dissected plateau on the Allegheny Plateau.

We are told the “Endless Mountains” are comprised of sedimentary rocks of sandstone and shale that were part of a lowland that collected sediments from mountains to the southeast that eroded millions upon millions of years ago.

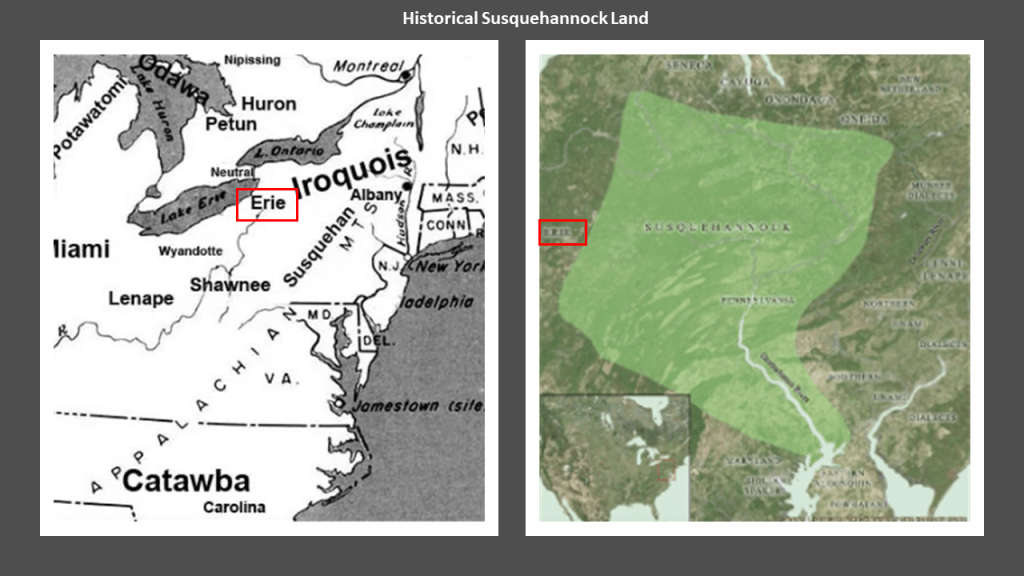

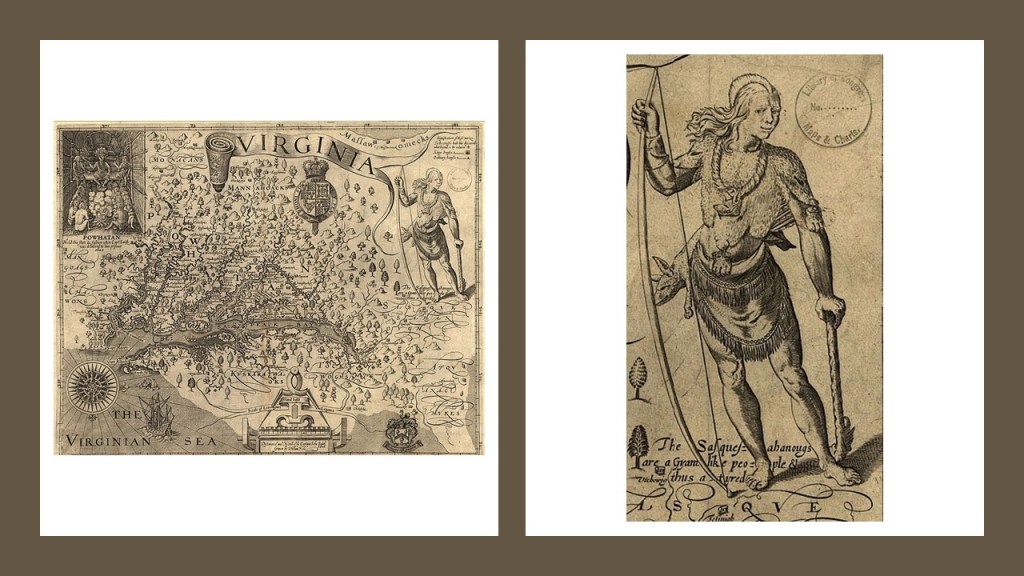

This region was historically inhabited by the Susquehannock, Iroquois, and Munsee-Lenape peoples.

Here are some pictures from the “World’s End State Park,” in the “Endless Mountains.”

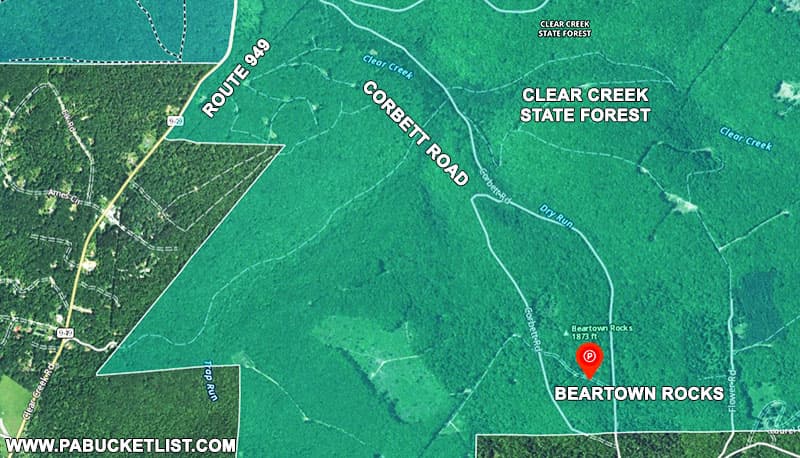

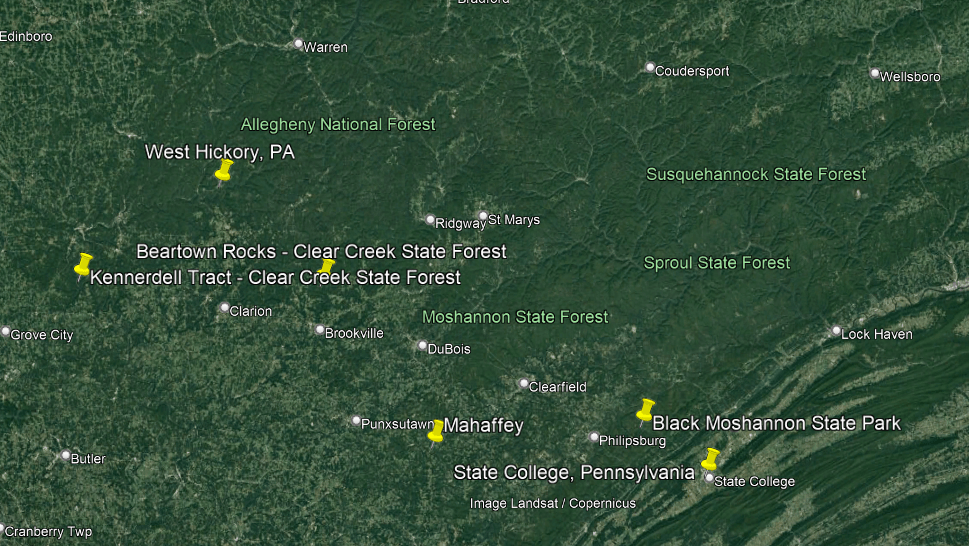

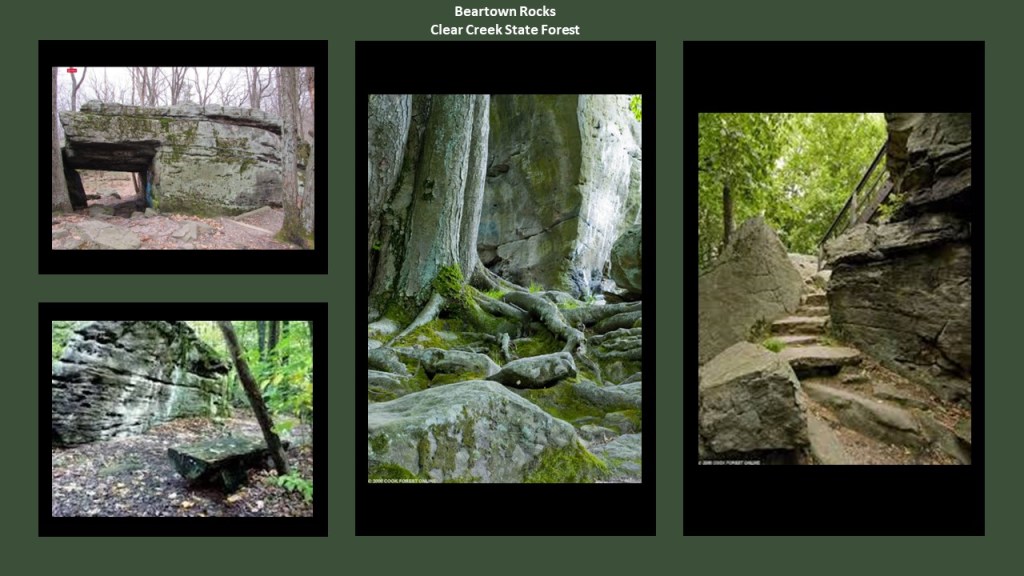

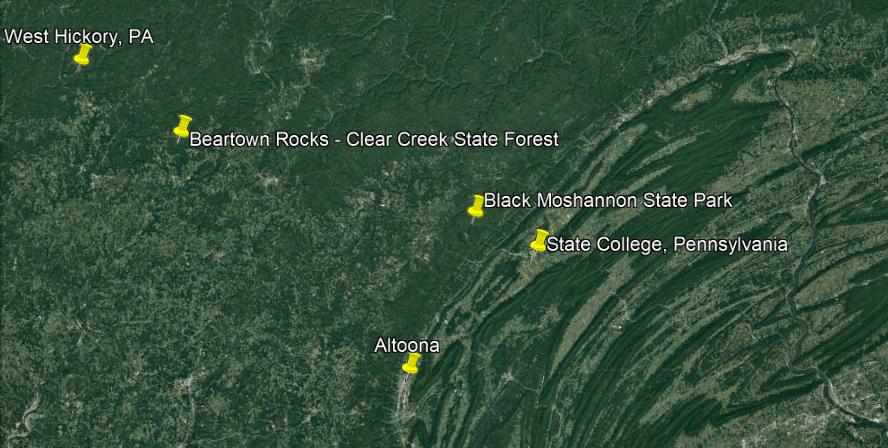

Beartown Rocks can be found in Clear Creek State Forest near Sigel, Pennsylvania, in Jefferson County.

With a population a little bit larger than Forksville, Sigel has a small population of a little over 1,100 residents at last count.

We are told was laid out as a community called Haggerty by Joseph Haggerty in 1850, and was renamed “Sigel” in 1865 after Civil War Major General Franz Sigel.

It is located at the intersection of Pennsylvania Route 32 and Pennsylvania Route 949.

This is what we are told.

Clear Creek State Forest was formed because of the depletion of old-growth forests by lumber and iron companies that took place in the mid-to-late-19th-century.

The forests were clear-cut, and wildfires caused by the sparks of passing steam kept the formation of new-growth forests from occurring.

Conservationists became alarmed that the forest would never re-grow, so they lobbied the state to purchase the land from the lumber and iron companies, which they were happy to sell because they had been depleted of resources.

The land that became the Clear Creek State Forest was purchased in 1919, at the end of the “lumber-era” that had swept through the Pennsylvania Mountains, by the end of which, Pennsylvania was stripped of its old-growth forests.

The entire park was established on three tracts of land in five Pennsylvania counties – Jefferson, Venango, Forest, Mercer, and Clarion.

Beartown Rocks in the part of the park in Jefferson County near Sigel are described as a beautiful rock formation consisting of “house-sized” boulders, that are spread out far enough they have road-like spaces in-between them, making it feel like a “rock city.”

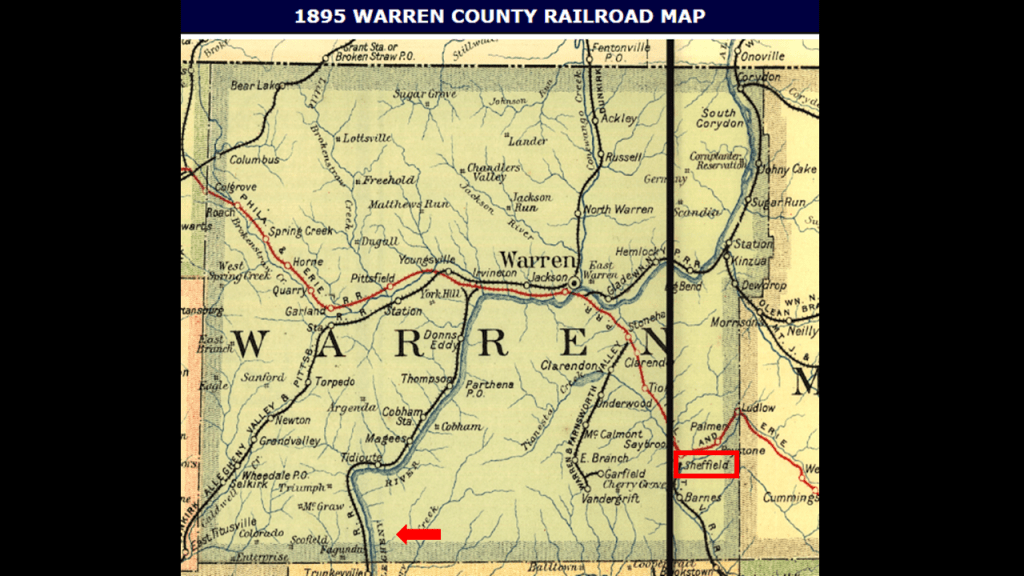

In the section of the park in Venango County, I found references to an historic railroad that ran along-side the curvy Allegheny River in the Kennerdale Tract of the Clear Creek State Park in Venango County that is now part of the hiking trail system here.

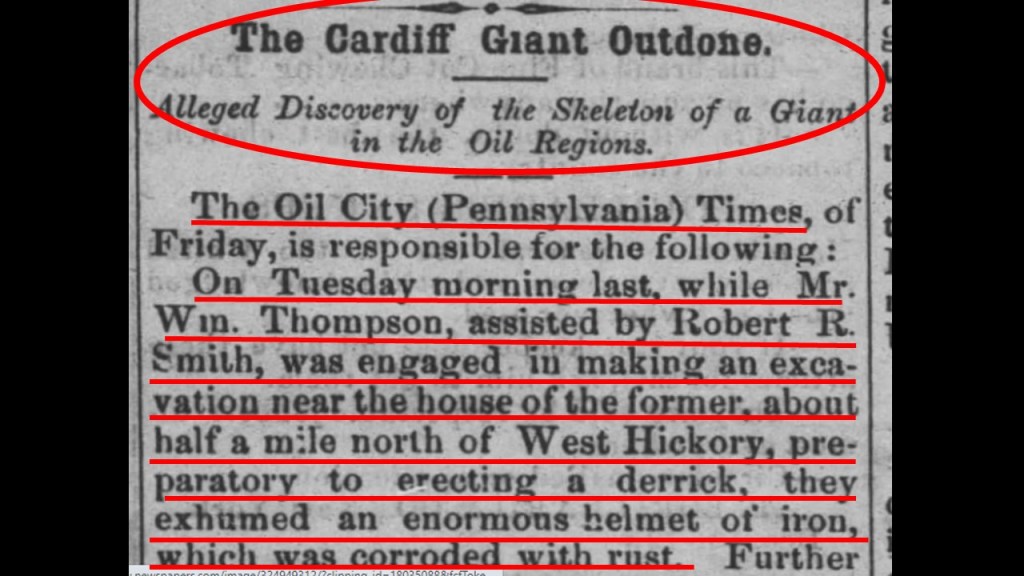

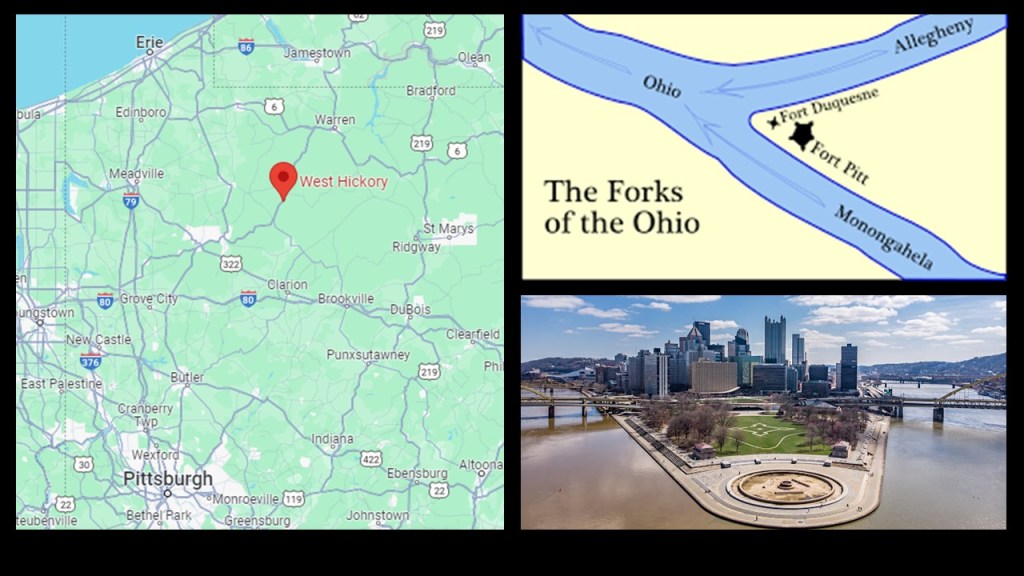

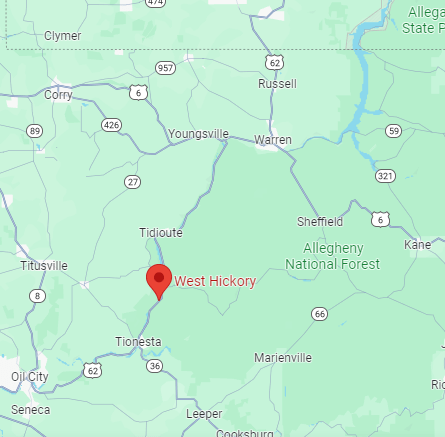

The Clear Creek State Park is very close to West Hickory, Pennsylvania.

As a matter of fact, these other places I am looking at are close to West Hickory too!

More on this as we go.

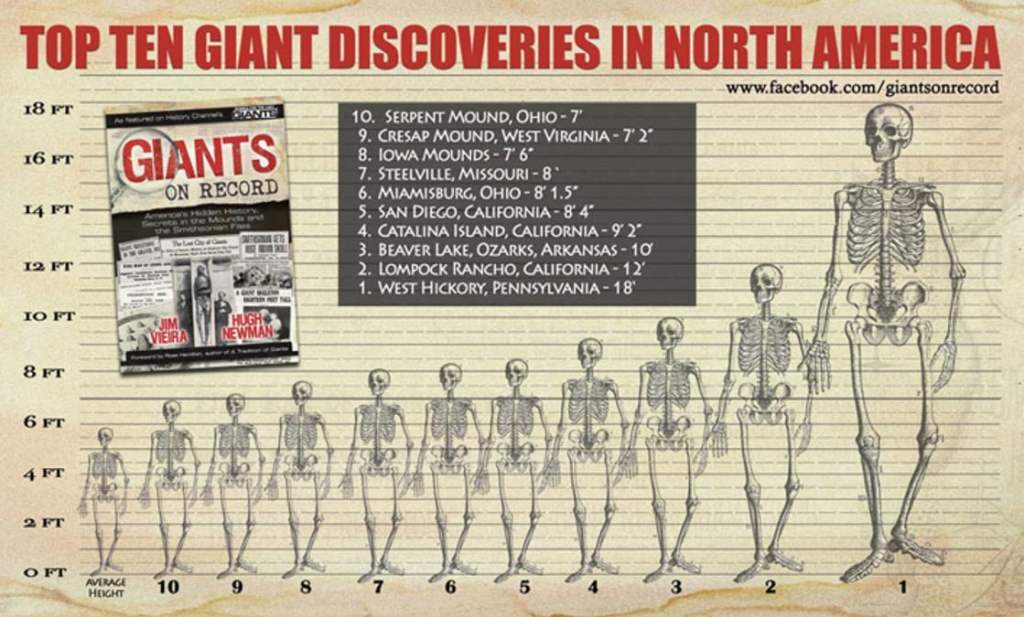

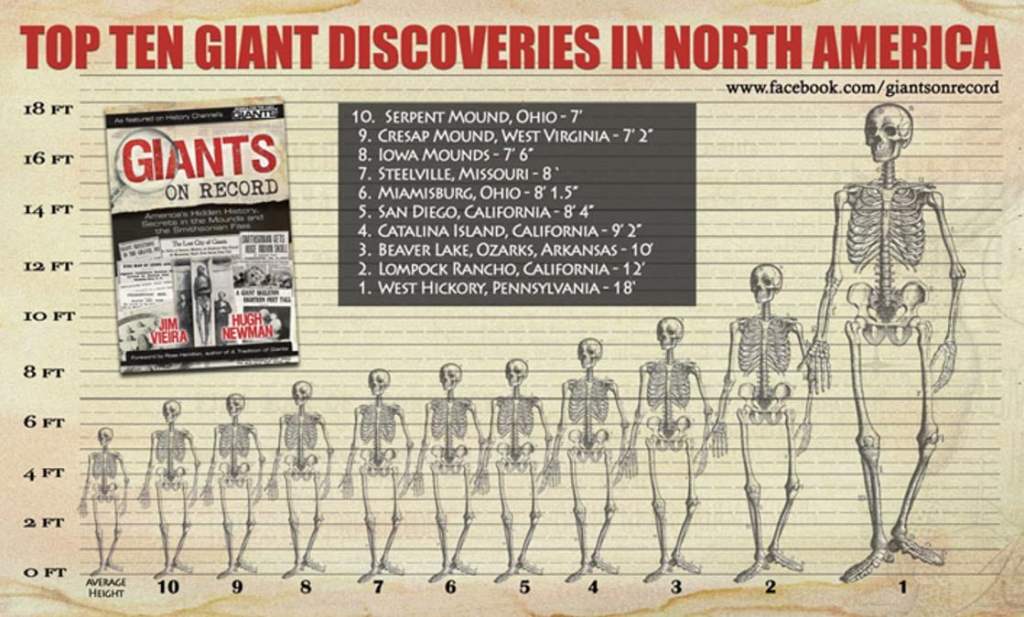

West Hickory is where the tallest recorded skeleton in North America was found, at 18-feet, 5.5-meters.

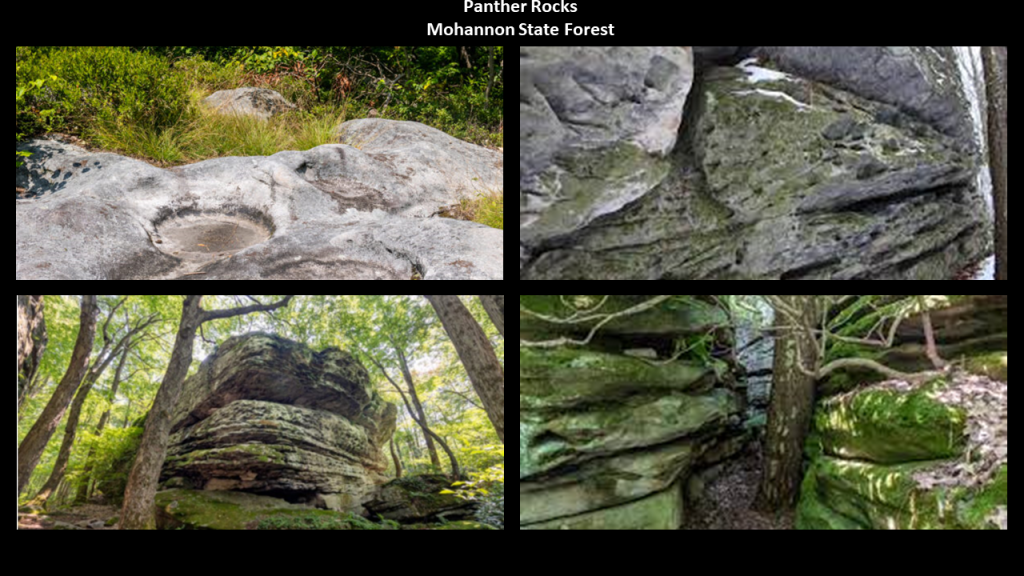

Next, he directed me to Panther Rocks in Moshannon State Forest.

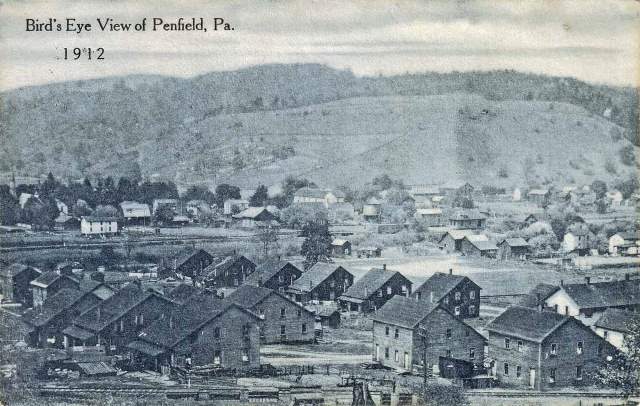

The forest is in five counties – Centre, Elk, Cameron, Clinton and Clearfield – with its main offices in Penfield, Pennsylvania in Clearfield County’s Huston township at the intersection of State Routes 153 and 255.

In the 2020 census, the population of Huston Township as a whole was recorded as a little under 1,300 people.

At one time in Penfield’s history, it was a company town for the logging and coal mining industries in what was a local resource extraction economy, and the railroad came through here at one time.

Immigrants from Europe settled in the area to work the deep mines scattered through the Benzette Valley here.

There’s not much left to speak of in Penfield, but there are recreational activities nearby at Moshannon State Forest, Bilger’s Rocks Park, Black Moshannon State Park, and Parker Dam State Park.

We find the same story at Moshannon State Forest that we found at Clear Creek State Forest – it was formed as a direct result of the depletion of the forests of Pennsylvania that happened in the mid-to-late 19th-century, when lumber and iron companies clear-cut the forests and sparks from passing steam-locomotives caused wildfires from the remnants of the forest-lands, preventing the growth of new forests.

The land that became Moshannon State Forest was purchased by the State in 1898.

The old-growth forest was gone by 1921, with a second-growth forest replacing it since then.

Interesting to note that a tornado in 1985 tore through the forest and destroyed an estimated 88,000 trees.

Panther Rocks at Moshannon State Forest are described as a small rock city made of several large sandstone blocks, complete with streets, overhangs, channels, crevices and a short tunnel

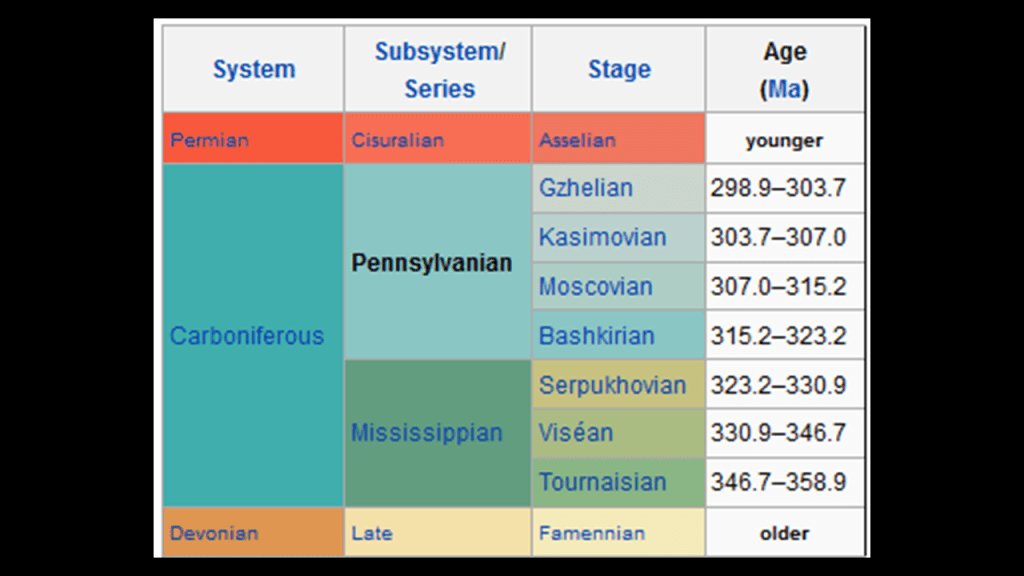

They were said to have formed during the Pennsylvania Age of the Carboniferous period of the Paleozoic era more than 300-million-years ago in the Pottsville Group, a rocks formed by sediments deposited in streams and rivers.

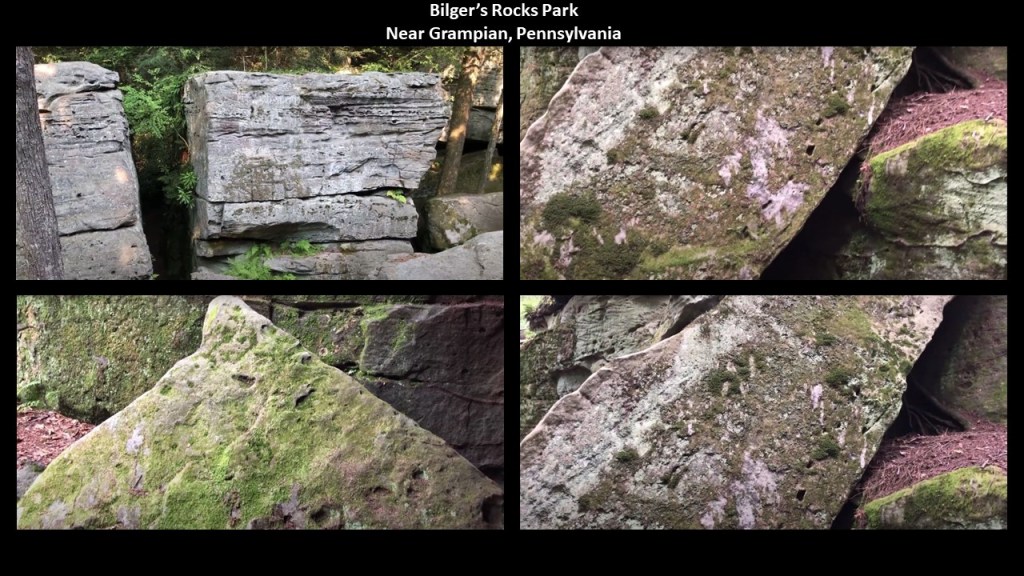

The nearby Bilger’s Rocks in Clearfield County’s Bloom Township near the town of Grampian, and is larger stone-city than what is found at Panther Rocks.

The creation of Bilger’s Rocks was also said to have taken place during the Pennsylvania Age of the Carboniferous period of the Paleozoic era more than 300-million-years ago, in the Homewood Formation of the Pottsville Group, a rock-unit formed by sediments deposited in streams and rivers.

Bilger’s Rocks has many examples of what appears to be toolmarks, and linear patterns that look like they were carved or molded, and has the same rock-city-like qualities of these other places we have been looking at tucked away in the Pennsylvania Park system.

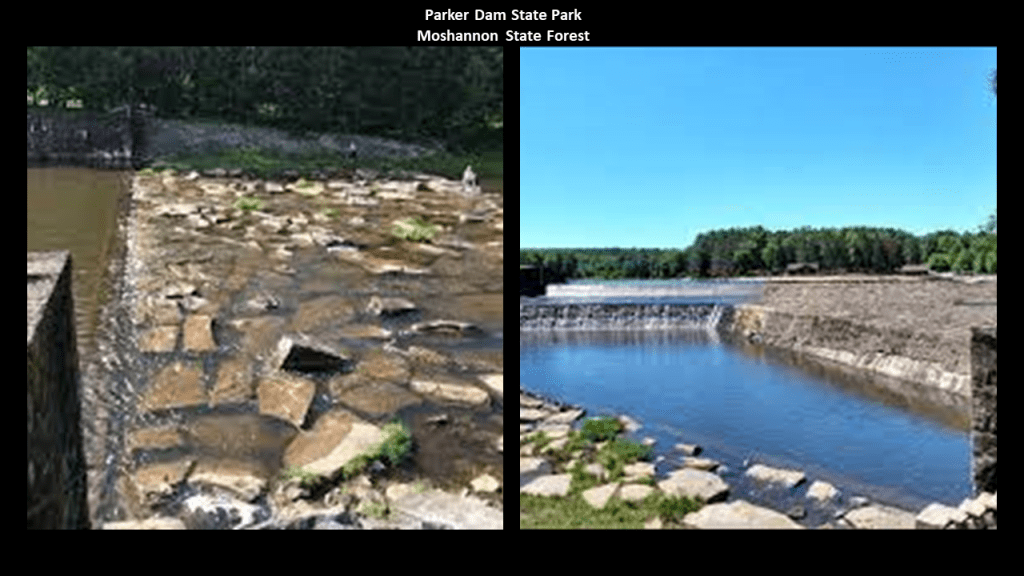

Parker Dam State Park is surrounded by the Moshannon State Forest.

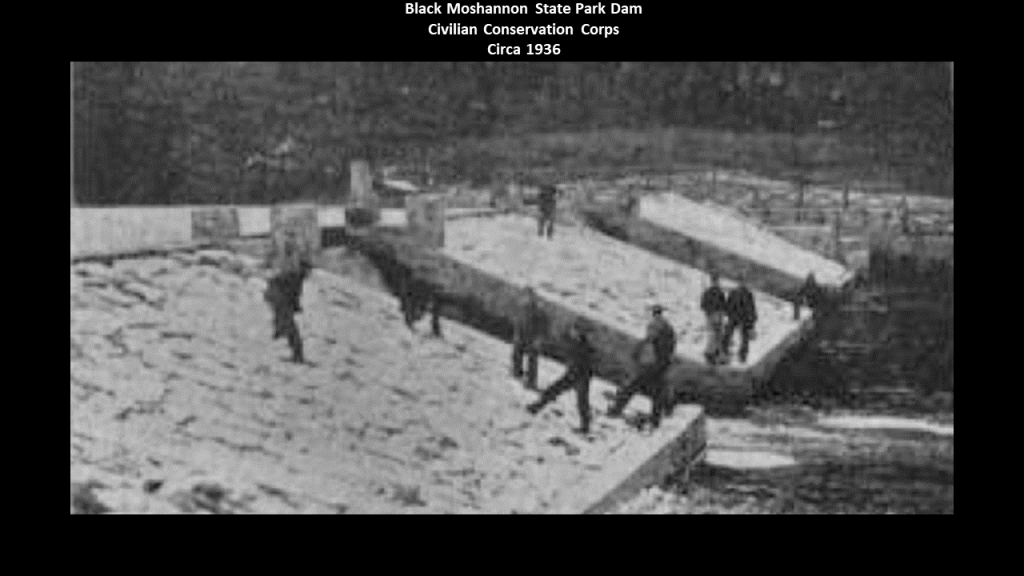

The Park was said to have been constructed by the Civilian Conservation Corps during the Great Depression.

The original dam here was said to have been constructed by William Parker as a splash dam for the movement of lumber after he leased lumbering rights at some point after lumber harvesting began here in 1794, and the CCC was said to have built the current dam there to replace it as part of the improvements the otherwise unemployed, unskilledyoung men made when they came to work on the park.

There was much logging going on from this region, so the “Susquehanna Boom” was said to have been built in the 1850s across the West Susquehanna River at Williamsport, a system of cribs and chained logs designed to catch and hold floating timber until it could be processed, and logging railroads built to transport the lumber, to the tune of 45-cars per day until logging ended here in 1911, when all the trees were gone.

The lumbermen left a barren landscape that was devastated by fires, flooding and erosion more many years, until the CCC came in the 1930s and started replanting trees after the State of Pennsylvania bought the deforested land from the Central Pennsylvania Lumber Company in 1930.

The Civilian Conservation Corps CCC operated from 1933 to 1942 in the U.S. for unemployed, unmarried men to do manual labor related to the conservation and development of natural resources in rural lands owned by federal, state, and local governments.

Originally for young men ages 18–25, it was eventually expanded to ages 17–28.

In the nine-years of its operation, the CCC employed 3,000,000 young men, providing them with food, shelter and clothing, and a wage of $30/month, $25 of which had to be sent home to their families.

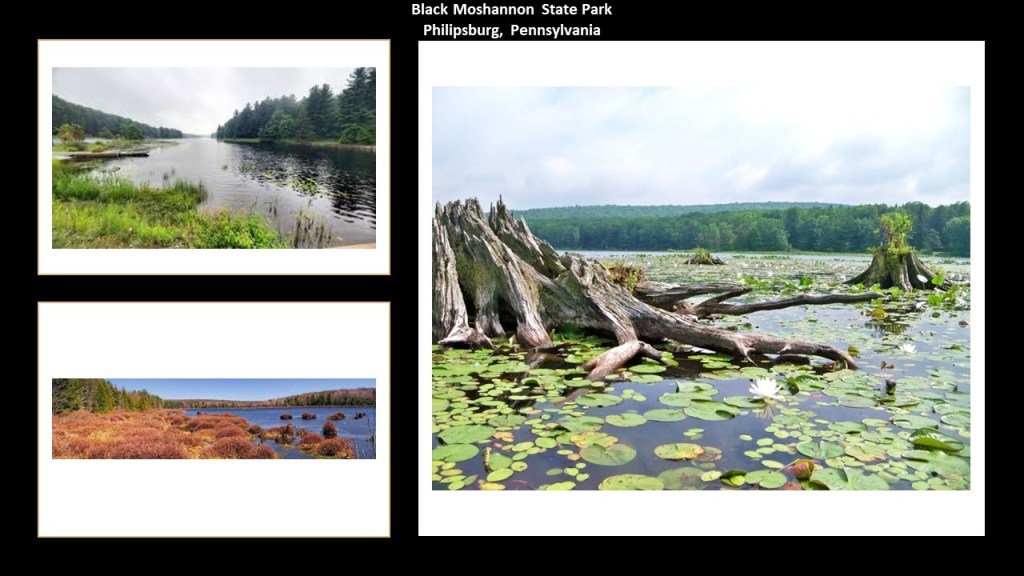

Black Moshannon State Park is largely surrounded by the Moshannon State Forest.

It is located in Rush Township in Centre County, and surrounds a lake formed by another dam, also said to have been constructed by the CCC, on Black Moshannon Creek at the site of a former mill-pond dam.

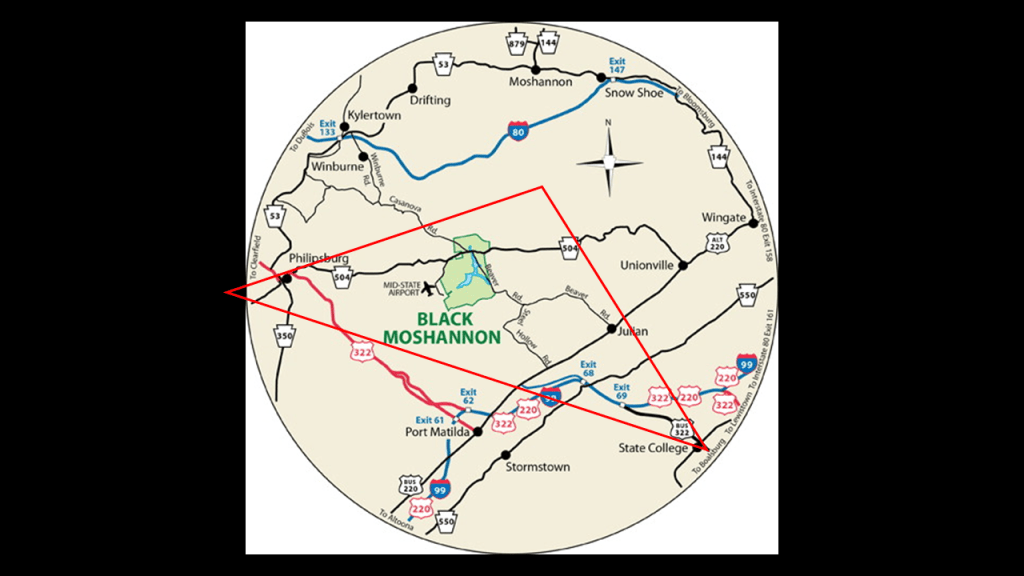

Black Moshannon State Park is is 9-miles, or 15-kilometers of Phillipsburg on Pennsylvania Route 504, and in Phillipsburg itself, other major roads that pass through are Pennsylvania State Routes 322, 350, and 53.

Philipsburg Borough was founded in 1797 by one Henry Phillips, who purchased 350,000 acres on the western side of the Allegheny Mountains for $173,000, and the proceeded to auction the land off on the streets of Philadelphia for two-cents per acre.

The region developed around the lumber and coal-mining industries.

Back to Black Moshannon State Park.

It is the home to the largest reconstituted bog in Pennsylvania, a wetland that accumulates peat as a deposit of dead plant materials, which contains carnivorous plants, orchids, and species typically found further north.

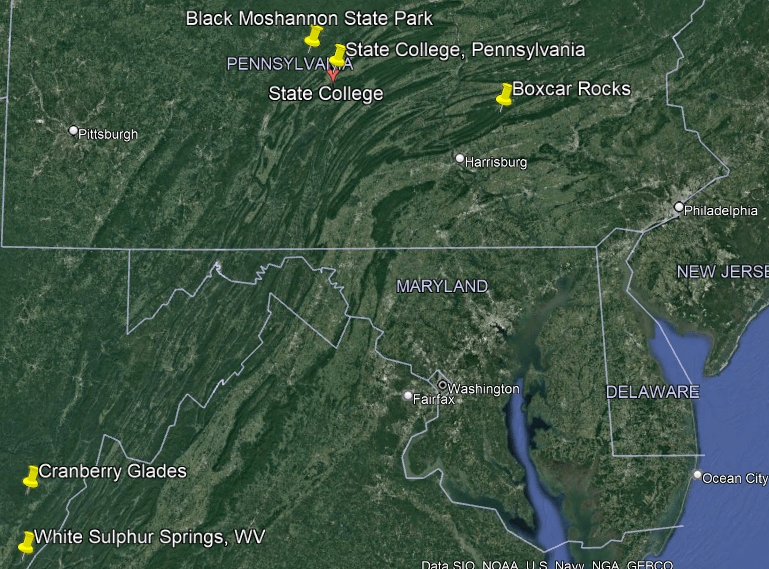

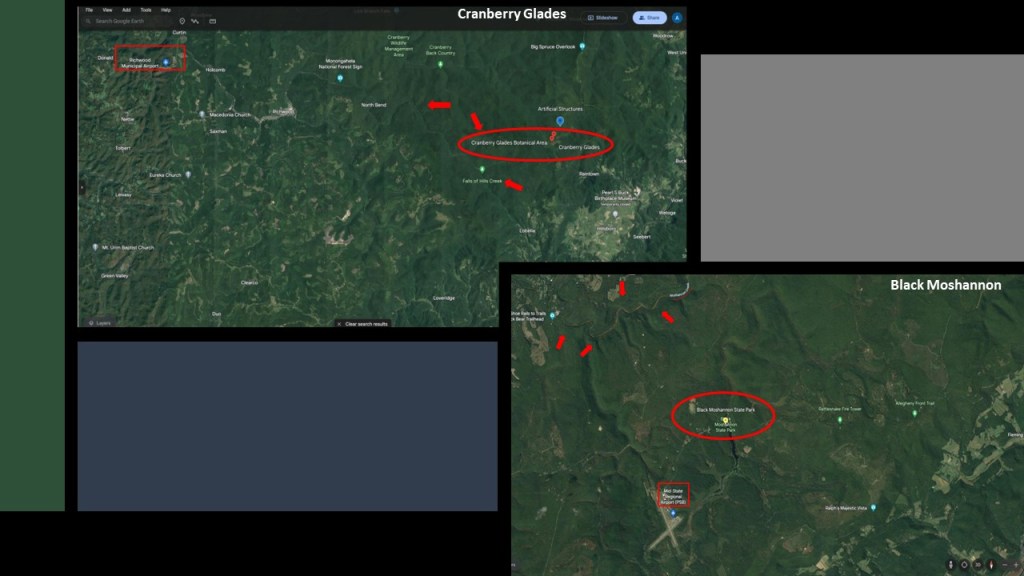

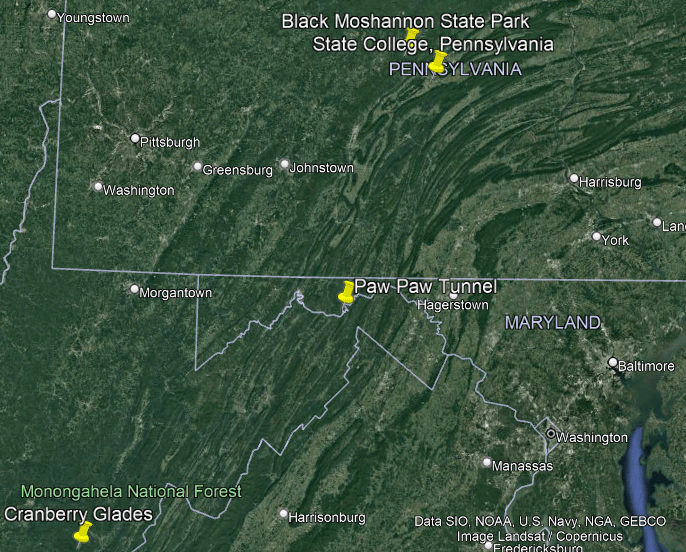

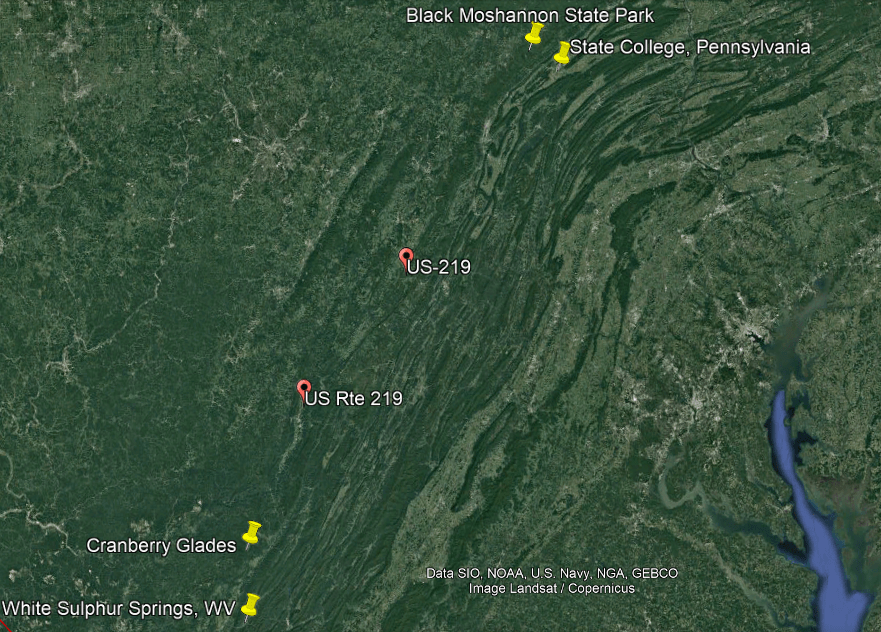

At this point I am going to bring in similarities between Black Moshannon in Pennsylvania and Cranberry Glades in West Virginia.

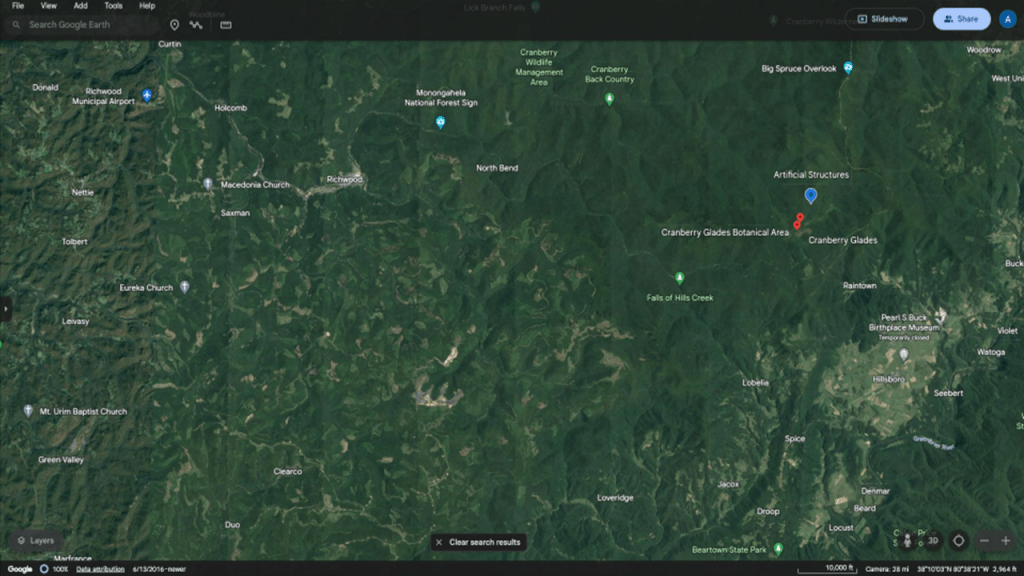

The boggy Black Moshannon State Park in Pennsylvania has a similar story as Cranberry Glades in West Virginia, which Aaron had mentioned at the beginning of our talk in “Uncovering Hidden West Virginia.”

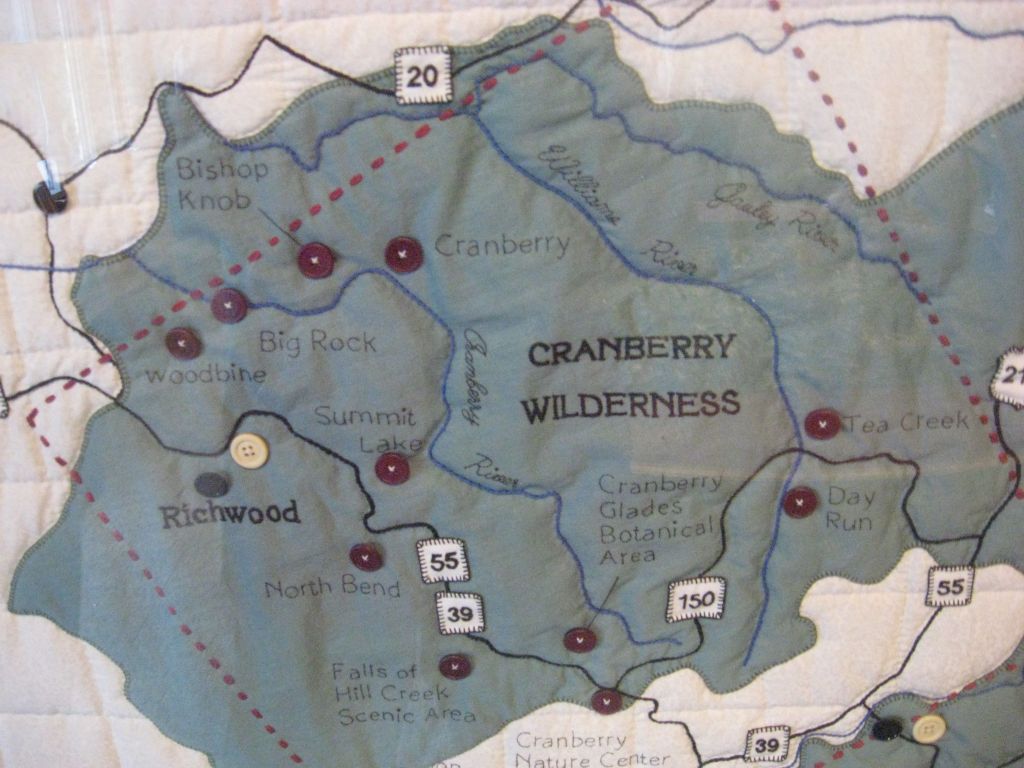

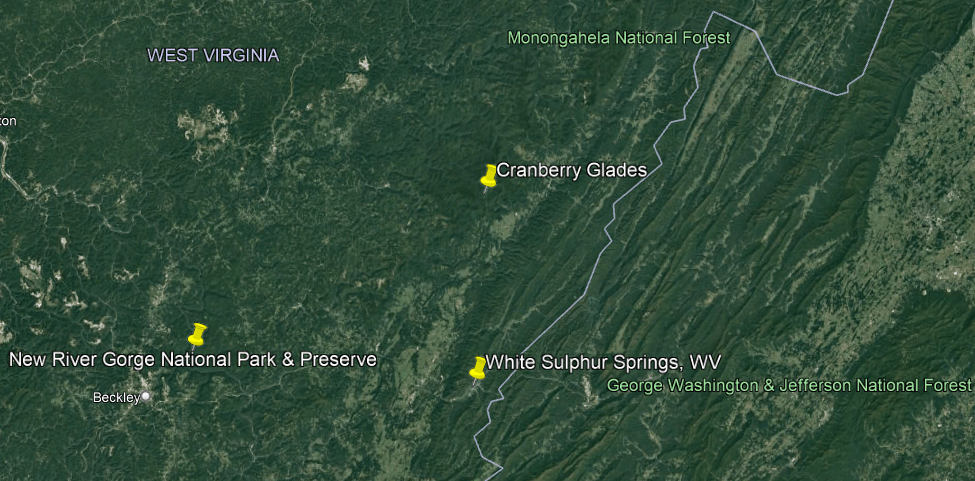

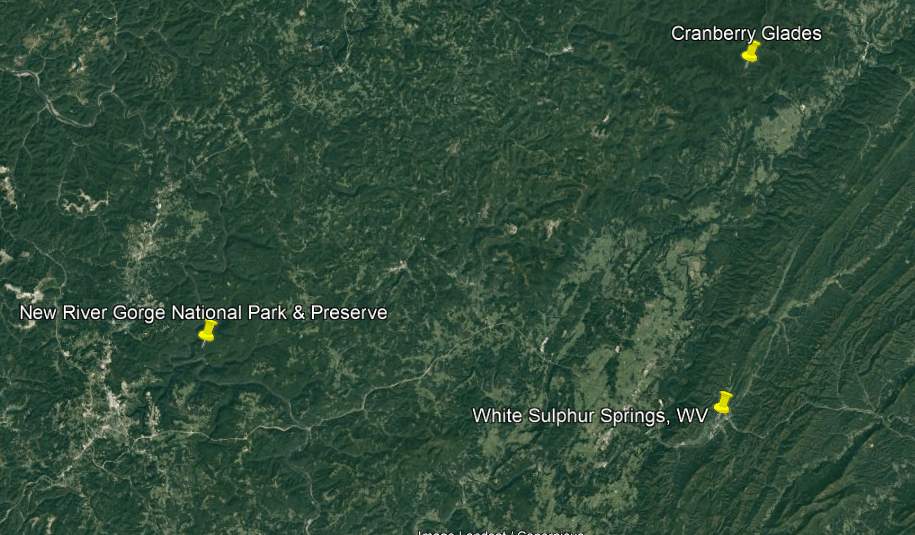

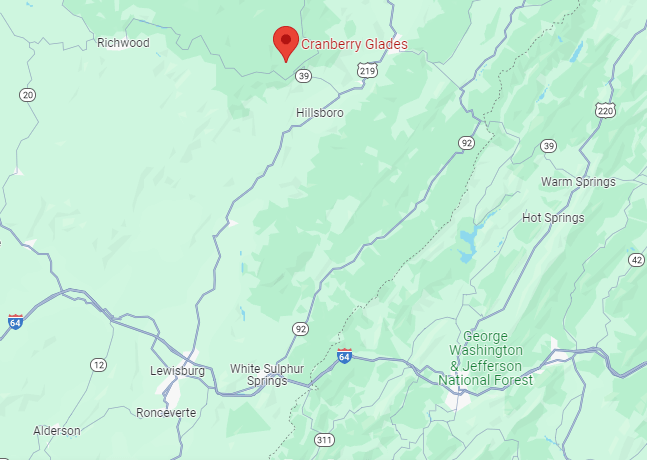

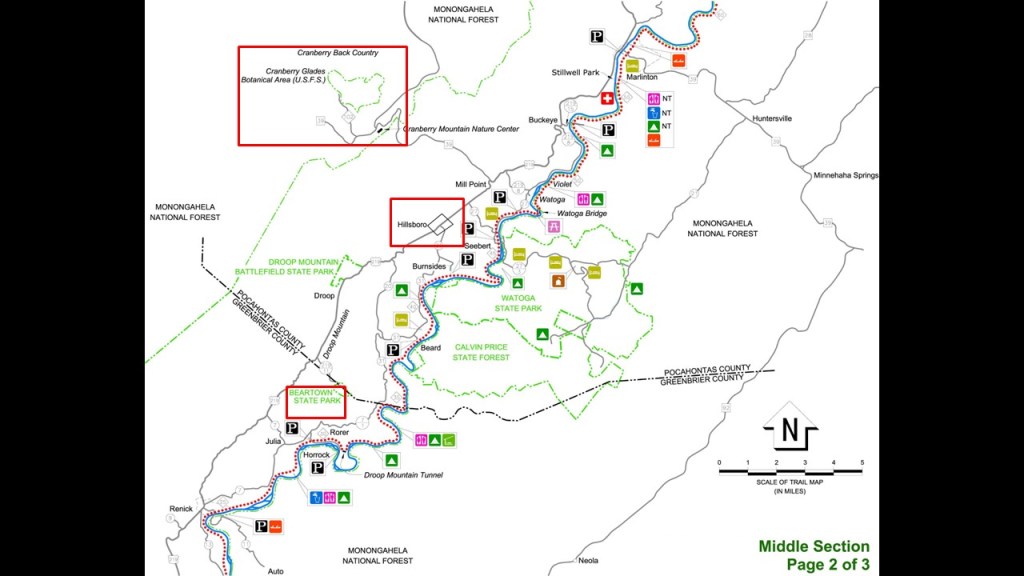

First, Cranberry Glades, protected in the “Cranberry Glades Botanical Area” area, are a cluster of five, separate boreal-type bogs in southwestern Pocahontas County in West Virginia, and like Black Moshannon State Park, the largest reconstituted bog in Pennsylvania, species are found at both these locations that are typically further north.

These species include cranberries, sphagnum moss, skunk cabbage, and carnivorous plants, and the Cranberry Glades are the southernmost home of many of the plant species found here.

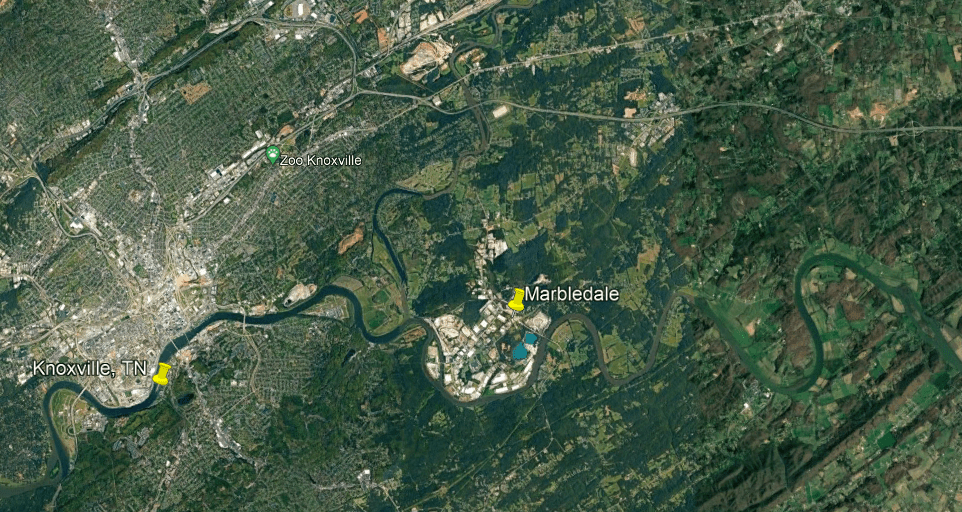

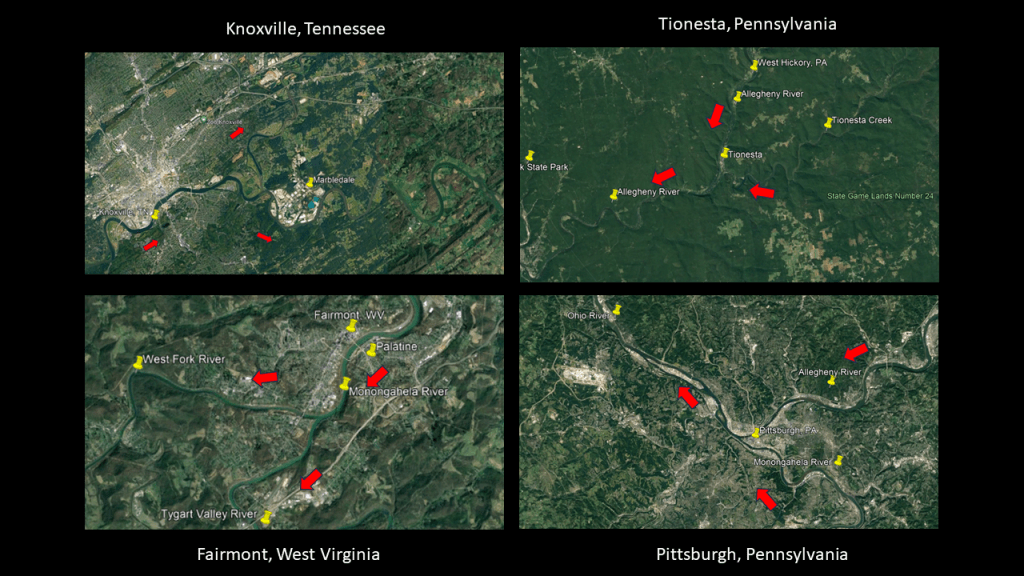

Both locations have s-shaped river bends and airports nearby, with the name of the parks notated by an oval; the airports by a box; and the river bends are pointed at by arrows.

The “Snowshoe Rails to Trails” is near Philipsburg and Black Moshannon is seen here in the top-left-hand corner, right next to the Moshannon River where the arrows are pointing.

The “Snowshoe Rails-to-Trails” has 19-miles, or 31-kilometers, of abandoned railroad bed along 37-miles, or 60-kilometers, of legalized Snowshoe Township Roads for ATVS/UTVs.

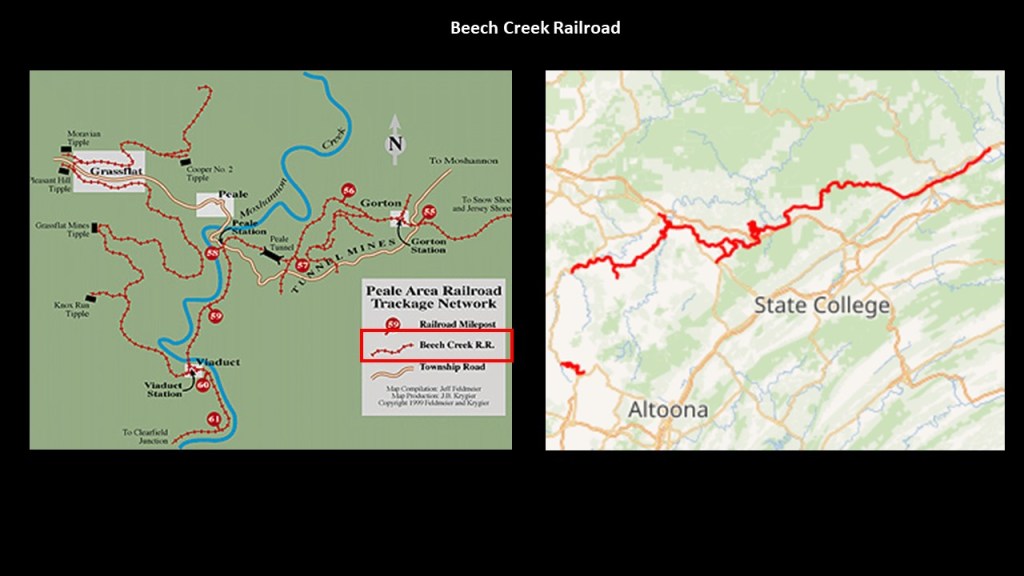

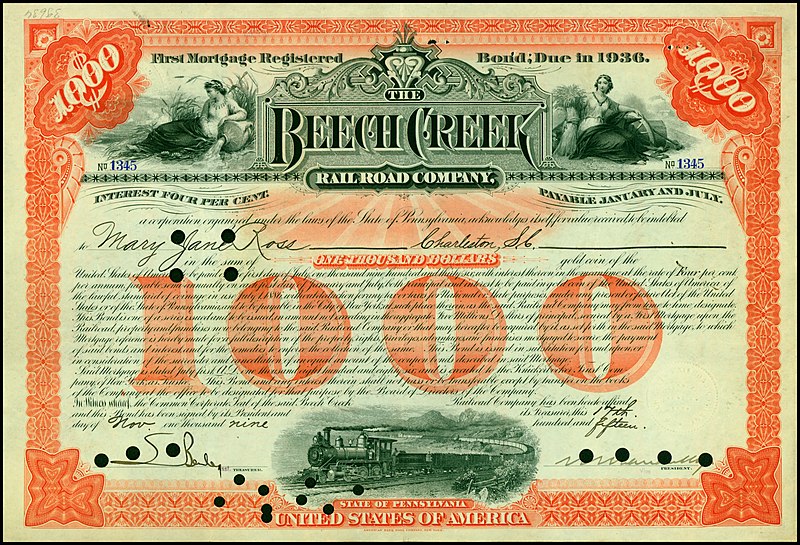

We are told that it was originally the route of the Beech Creek Railroad between the South Jersey Shore and Mahaffey Borough, Pennsylvania, and part of the Susquehanna and South Western Railroad, and used for coal mining services in the region starting in 1884.

So this railroad ran near State College, home of Penn State University, and not far from Altoona, Pennsylvania.

More on State College and Altoona to come in this post.

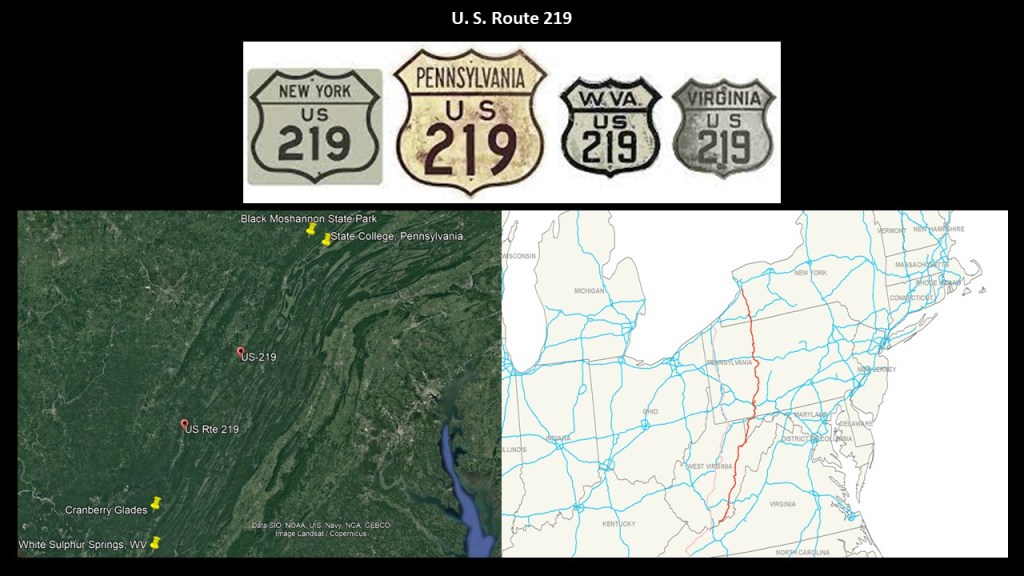

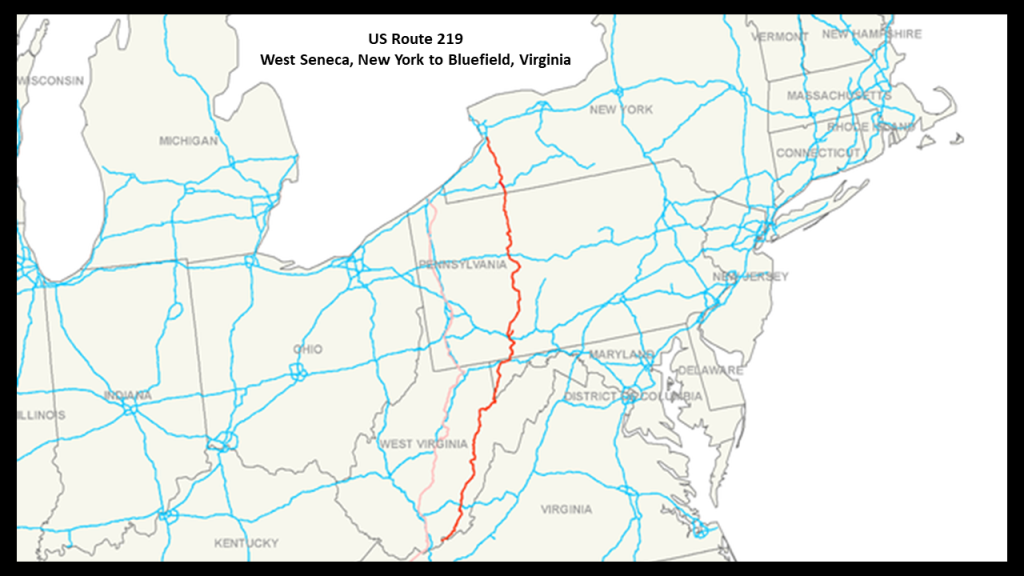

Mahaffey Borough, first incorporated in 1841, was located on U. S. Route 219, at the junction of the New York Central Railroad and the Hudson River Railroad.

The arrows point to where railroad tracks ran along s-shaped river-bends. on this section of Route 219 going through Mahaffey Borough.

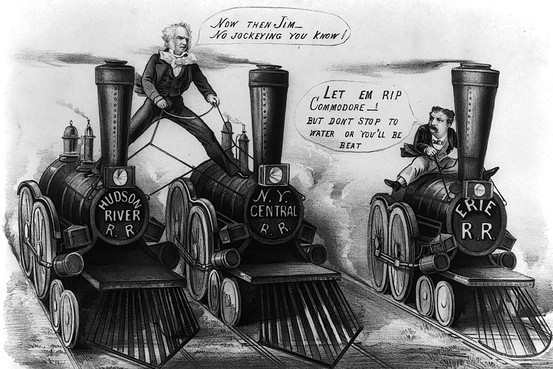

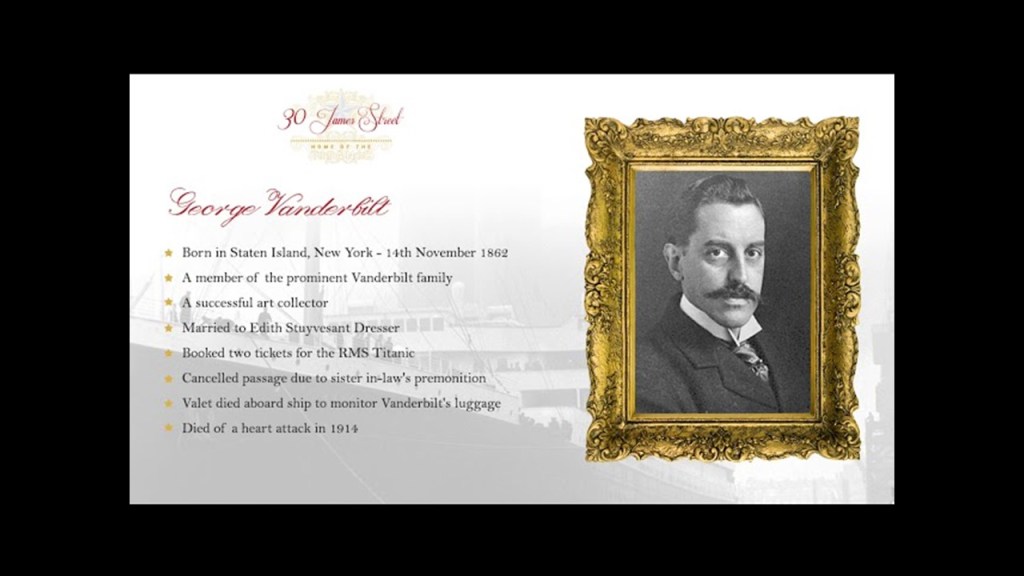

This railroad project in Pennsylvania was said to have been backed and financed by William H. Vanderbilt, President of the New York Central Railroad.

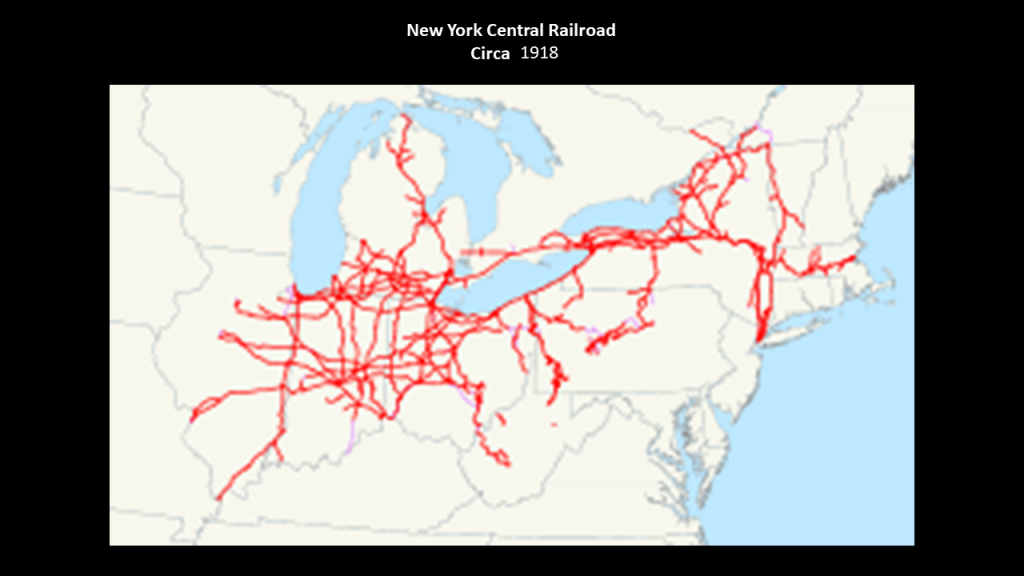

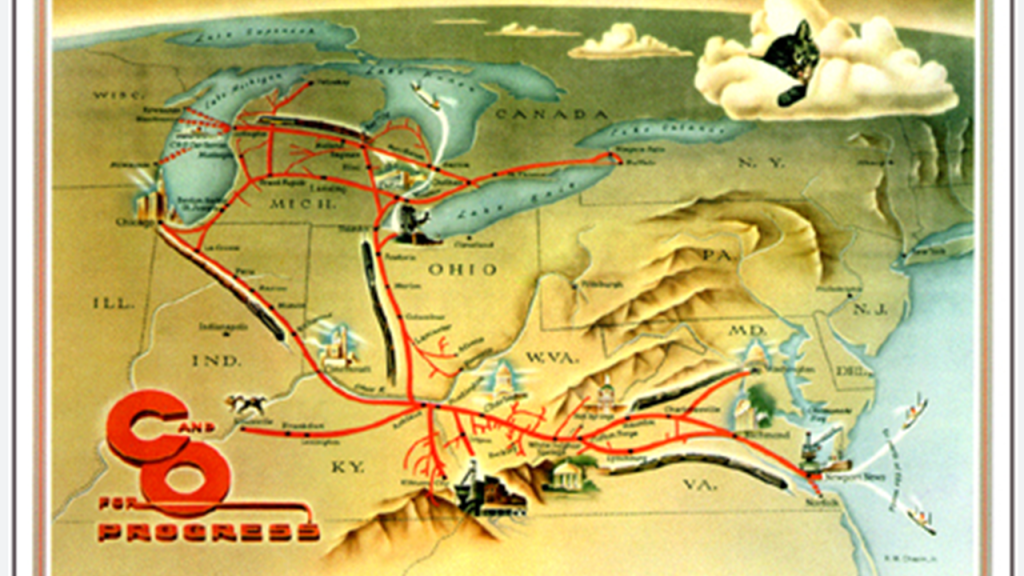

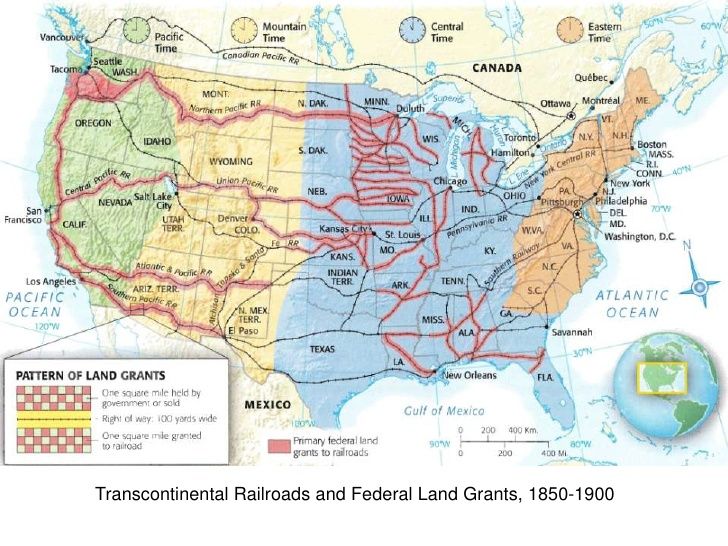

The New York Central Railroad was said to have begun operating in 1853 with the consolidation of earlier independent companies running between Albany and Buffalo. This graphic depicts the New York Central rail system as of 1918.

We are told extensive trackage existed in the states of New York, Pennsylvania, Ohio, Michigan, Indiana, Illinois, Massachusetts, and West Virginia, plus additional trackage in Ontario and Quebec, and by 1925 operated 26,395-miles, or 42,479-kilometers, of track.

William Vanderbilt had developed a plan to facilitate railroad access to enter the “Clearfield Coalfield,” a large, juicy coal-mining area in Clearfield County, which would have been otherwise exclusively accessed by the Pennsylvania Railroad.

It was said to have been constructed starting at the end of 1882 to high-standards, including extensive curvature, bridges, and a tunnel, and became operational in November of 1884.

Eventually, this railroad line provided passenger service and used as such until 1990.

In 1994, the right-of-way was acquired by the Headwaters Charitable Trust for the “Snowshoe Rail-to-Trail Project” and the rail went away.

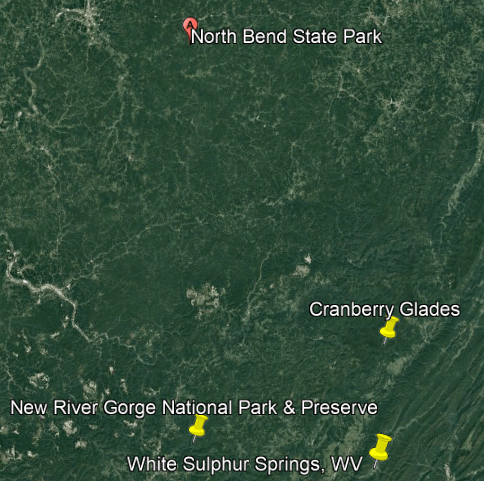

Cranberry Glades is located close to both the New River Gorge National Park and Preserve, and White Sulphur Springs.

First, New River Gorge National Park and Preserve.

The New River Gorge is one of the few places that I know of that still has a railroad operating right along beside the s-shaped New River.

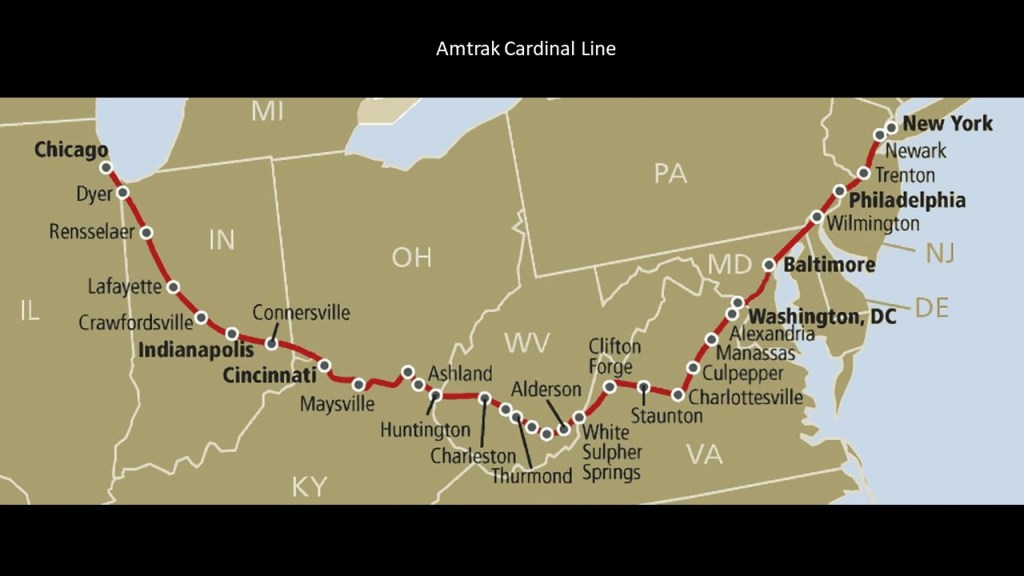

The Amtrak Cardinal still runs through the New River Gorge 3 days/week – on Sundays, Wednesdays and Fridays.

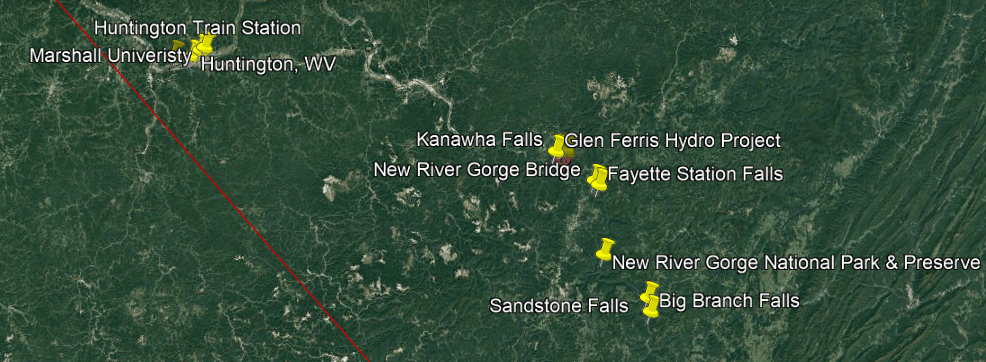

Besides the railroad line that runs along the New River through the New River Gorge in West Virginia, there are things found in the gorge like historic coal mines, waterfalls, and hydro projects.

We are told that after the Chesapeake and Ohio Railway opened up this rugged wilderness in 1873, coal was carried out of the New River Gorge to the ports in Virginia and to cities in the Midwest.

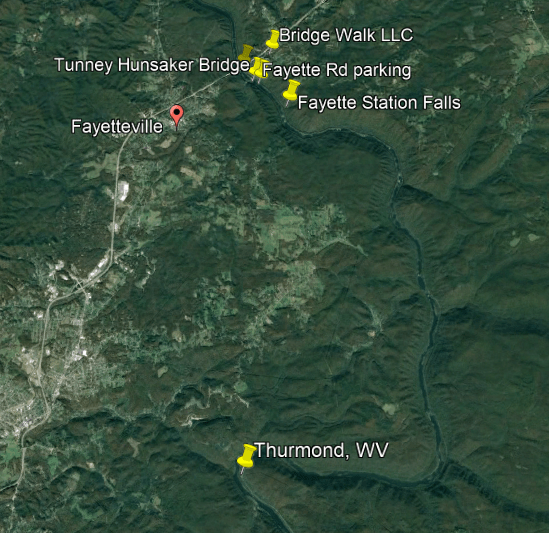

As a result, by 1905, thirteen cities sprang up between Fayette and Thurmond, which was 15-miles, or 24-kilometers, upstream, and provided the West Virginia coal that contributed greatly to the industrialization of the United States until the 1950s.

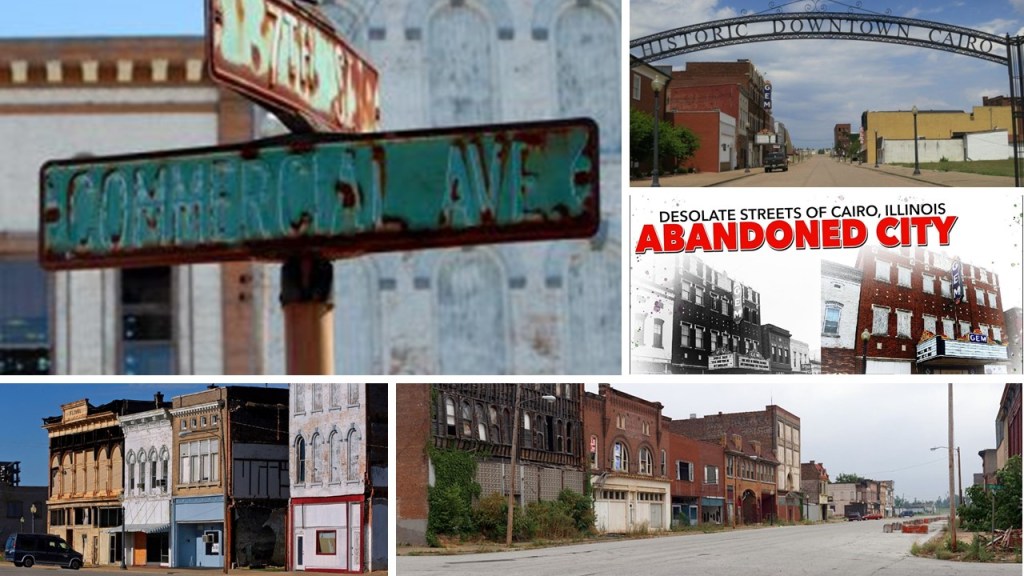

After the coal seams were exhausted and mines closed, these company towns like Fayette were for the most part completely abandoned, with the possible exception of Thurmond which had a very small population of 5 in 2010.

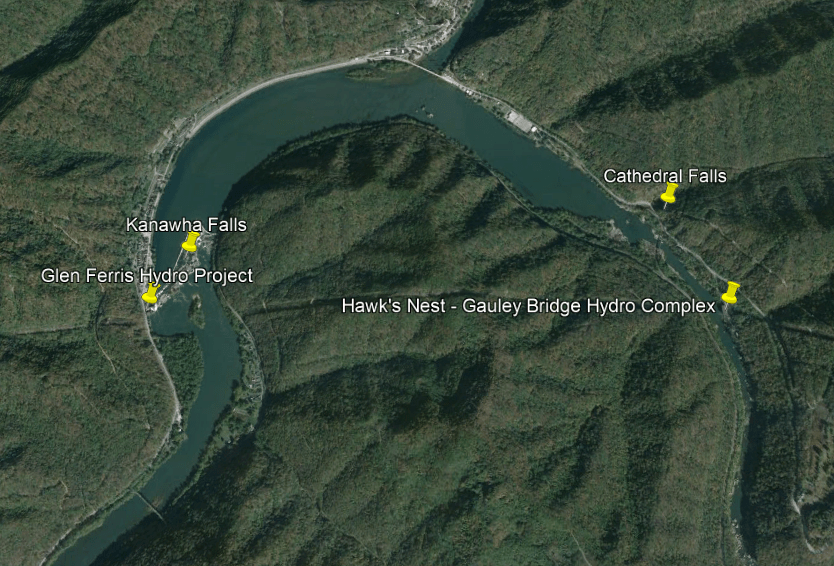

There are waterfalls and hydro-electric projects found on the New River as it winds its way through the gorge.

I was able to find several waterfalls here that are accessible by road, and reference to over 100 others .

The first two waterfalls I found that are accessible by road are the Kanawha Falls and Cathedral Falls.

They are directly across from each other on a river-bend, and they both have hydro projects next to them.

There is no doubt in my mind that there was an energy-generating connection for the original civilization between the railroad, s-shaped river bends, hydro-electricity generation, waterfalls and gorges.

I researched these finding extensively in my blog post “Of Railroads and Waterfalls and Other Physical Infrastructure of the Earth’s Grid System.”

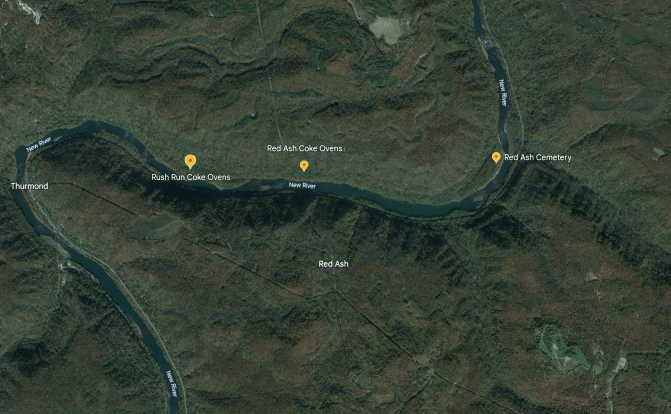

Aaron sent me information about the Red Ash and Rush Run Coke Ovens near Thurmond.

It is interesting to note that at one time in its history, Thurmond was a prosperous railroad town that was the largest, revenue-generating stop on the C & O Railroad, where passenger and coal trains rolled through here throughout the day.

Today, a visitor center for the National Park Service operates here in the old railroad depot.

CSX Transportation, formerly the C & O Railroad, has freight transportation operations in and through historic Thurmond, and the Amtrak Cardinal passenger route goes through here, the second-least-used Amtrak station in the nation.

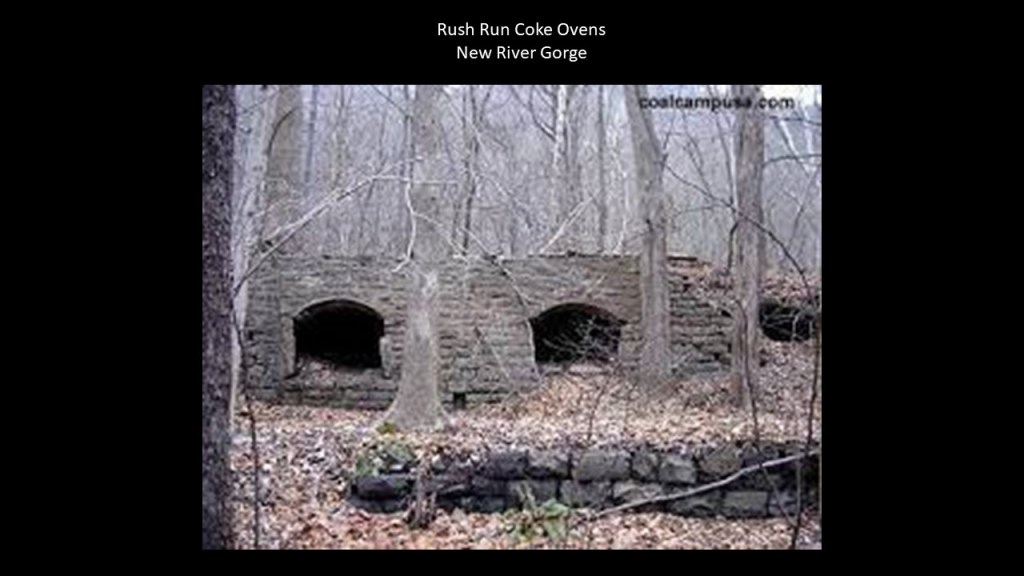

The Rush Run Coke Ovens were said to belong to the Rush Run Mining Company, and there believed to have been up to 180 of them at this location, which borders the railroad tracks.

Coke ovens are described as being made of brick, or some kind of heat-resistant material, and used to separate the coal-gas, coal-water, and tar.

Coke is formed when the coal-gas and coal-water fuse together, and is used primarily in steel-production.

Rush Run was established as a coal-mining community in `1889 when the post opened first opened, and boomed until the post office closed 1939.

The mine there continued to operate until it was closed in the 1940s.

The nearby Red Ash coal camp was developed by the Red Ash Coal and Coke Company in 1891, for a high-quality coal that burned with a “fine red ash.”

There were estimated to be 80 coke ovens here at one time, and the mine was exhausted by the 1950s.

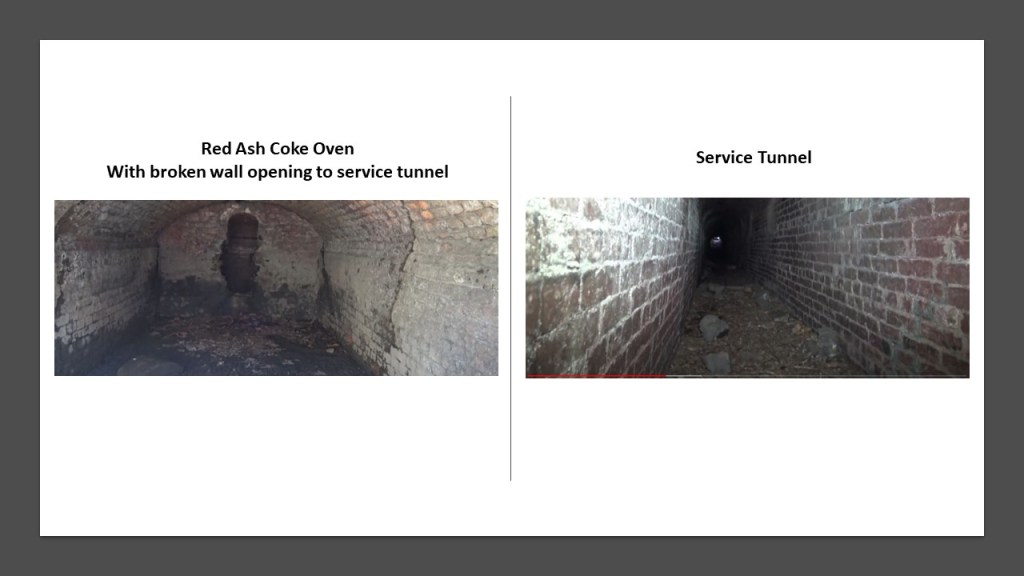

There’s a service tunnel at the location of the Red Ash Coke Ovens.

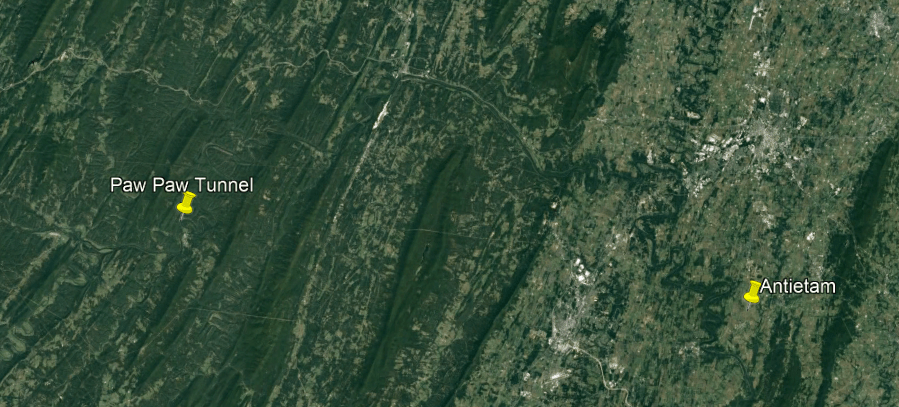

The fine brick-work found at the Red Ash facilities reminds me of the fine brickwork I have seen in tunnels all over the place, including what is called the Great Tunnel of the C & O Canal in Allegheny County, Maryland, and part of the Paw Paw Bends section of the Potomac River as it is winding its way through West Virginia and Maryland.

Built using more than 6,000,000-bricks, this tunnel has been described as the “greatest engineering marvel along the Chesapeake and Ohio Canal National Historical Park.”

It is located roughly mid-way between Black Moshannon State Park in Pennsylvania and Cranberry Glades in West Virginia…

…and isn’t far from the Antietam National Battlefield in Maryland, which is also on the Potomac River, and a place where I will be talking about later in this post.

The Paw Paw Tunnel was said to have been built between 1836 and 1850 for the C & O Canal to by-pass the bends in the Potomac River near Paw Paw, West Virginia, with no work having been done on it between 1841 and 1847 due to construction and financial problems.

The C & O Canal closed to canal boats in 1924.

Canals, like the railroads, were found running next to rivers, and the Potomac River is a good example of this, like here where the canal and the railroad run side-by-side at Point of Rocks, Maryland, before they both enter Harper’s Ferry, West Virginia.

We are told that the C & O Canal, and other canals, were made obsolete because the railroad was so much more efficient and canals couldn’t compete with them.

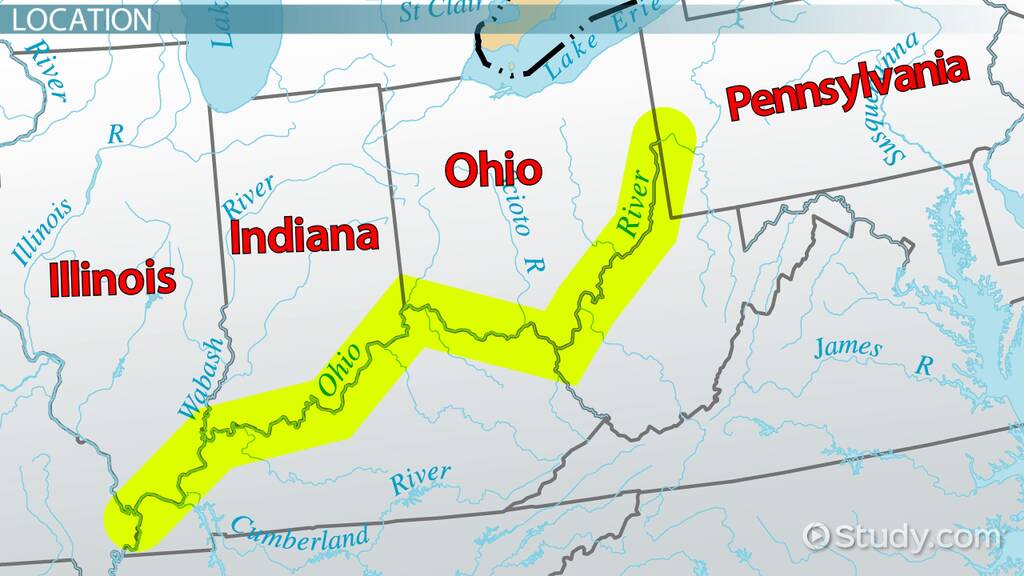

Such as the Wabash and Erie Canal, which was said to have been built during roughly the same time period as the C & O Canal.

Canals like the C & O Canal subsequently became a popular hiking, biking and canoeing venue, as we are seeing with the Rails that quietly became trails when no one was paying attention.

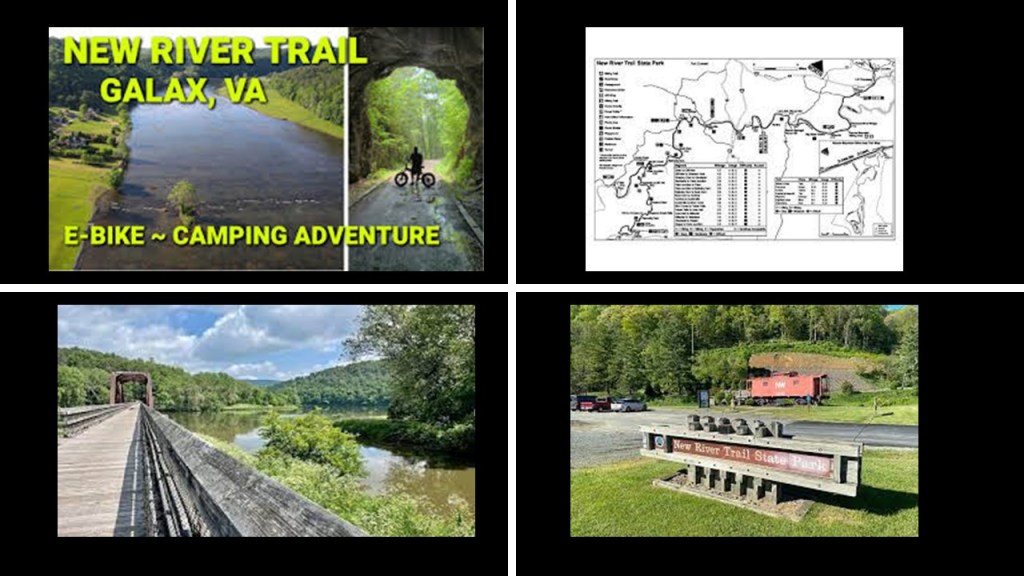

So whereas the railroad that runs alongside the New River in the New River Gorge is still operational for freight and passenger service, the railroad that used to run beside the New River in Galax, Virginia, to the southwest of the New River Gorge, was abandoned in 1985, and the former railroad right-of-way became the New River Rail Trail.

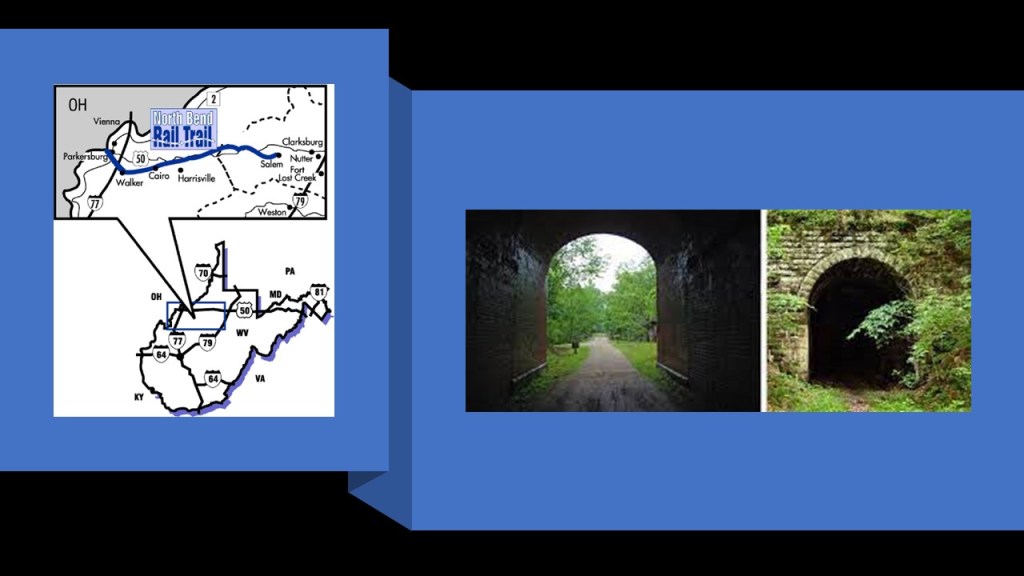

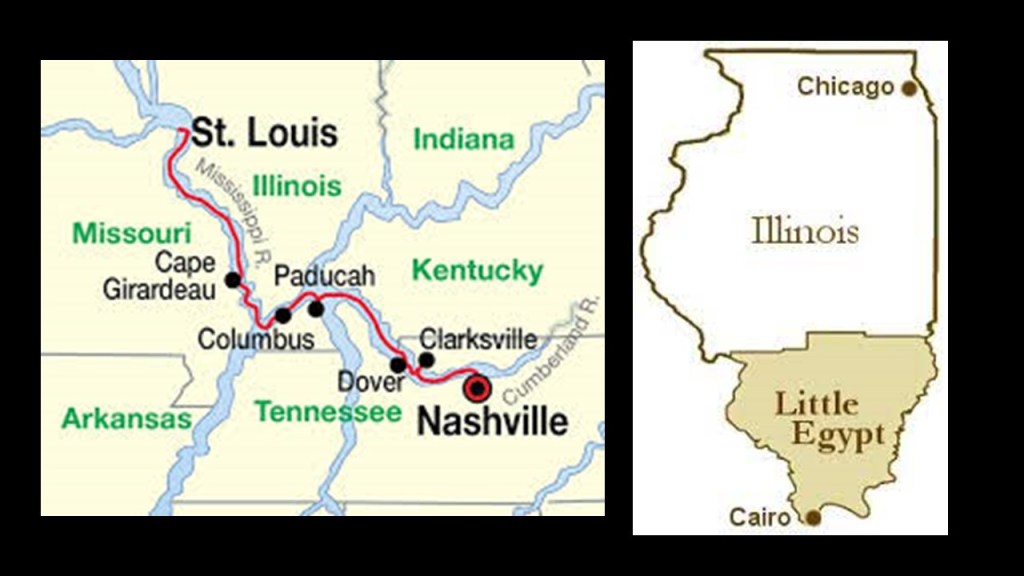

And starting at the North Bend State Park in Cairo, West Virginia, northwest of Cranberry Glades and northeast of the New River Gorge, there is the 72-mile, or 116-kilometer, – long hiking corridor known as the “North Bend Rail Trail” running between Cairo and Ellenboro, West Virginia.

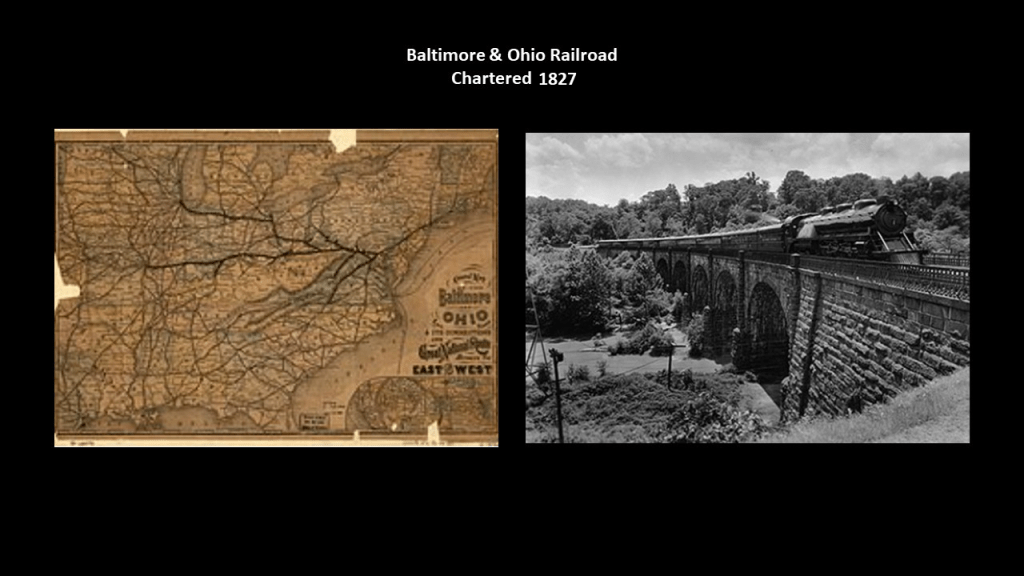

What is now the North Bend Trail was at one time one of the most distinguished railroad lines in United States History.

It was said to have been constructed between Grafton, West Virginia, and Parkersburg, West Virginia, by the Northwestern Virginia Railroad between 1851 and 1857, at which time it was sold to the Baltimore & Ohio Railroad and became known as the “B & O Parkersburg Branch.”

The Parkersburg Branch was said to have been built to high engineering standards with 23 tunnels and 52 bridges to minimize curvature, and had a maximum grade of 1.5%

During its prime, it hosted the B & O Railroad’s premiere passenger train, the National Limited, between New York City and St. Louis, Missouri.

In 1827, the State of Maryland chartered the Baltimore and Ohio (B & O) Railroad, the first common carrier, and the oldest, railroad in the United States.

The first section of the B & O Railroad was said to have opened in 1830, and it was said to have reached the Ohio River in 1852, the first eastern seaboard railroad to do so.

Unfortunately, we are told that with the rise of automobile ownership, ridership declined, and B & O ended its passenger service in 1971, at which time Amtrak took over and passenger service continued for another ten-years.

Eventually the rail-line that was part of the North Bend Rail Trail became freight-only, and the line was abandoned and dismantled in 1988.

The trail was completed between 1991 and 1996, and also has beautiful, red-brick tunnels along the way.

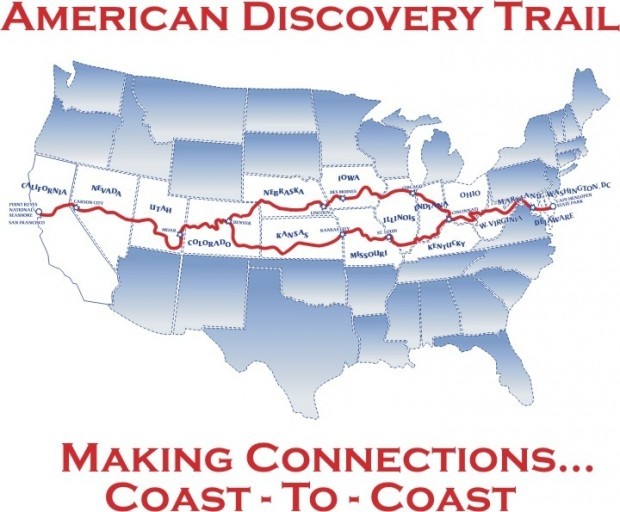

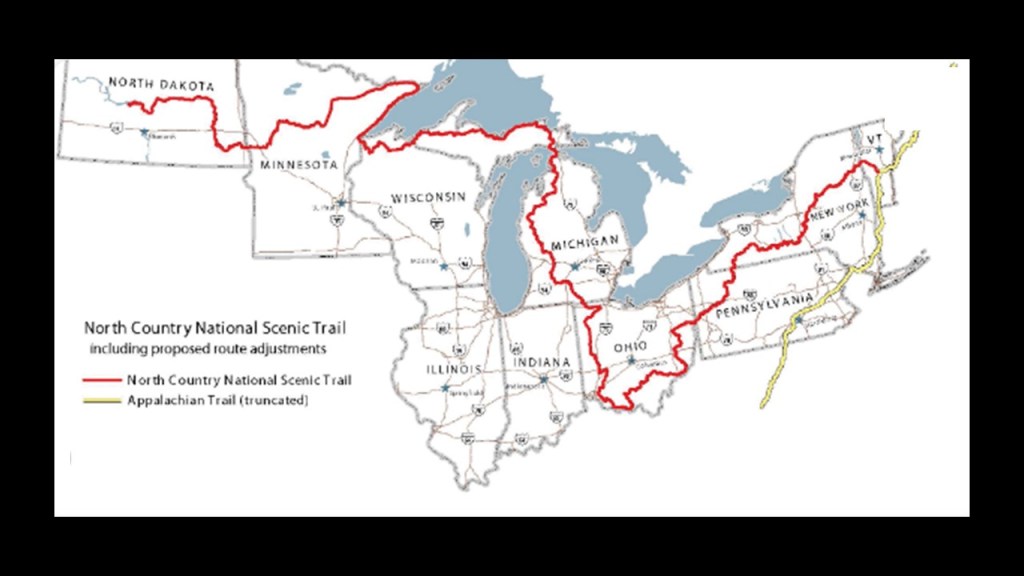

The North Bend Rail Trail is part of the “American Discovery Trail,” that runs from coast-to-coast through 15-states and the District of Columbia, and is the only non-motorized trail that crosses the country.

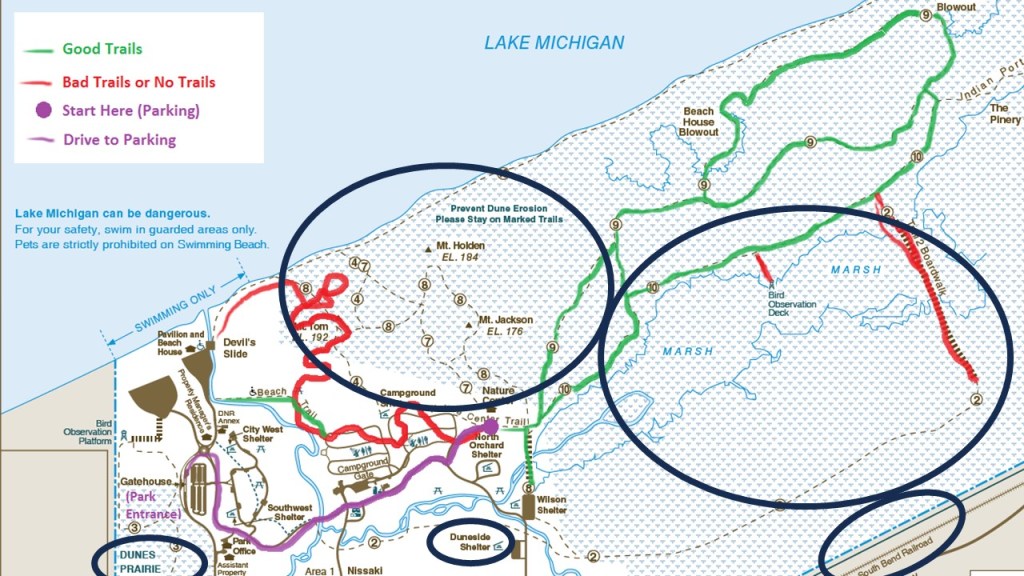

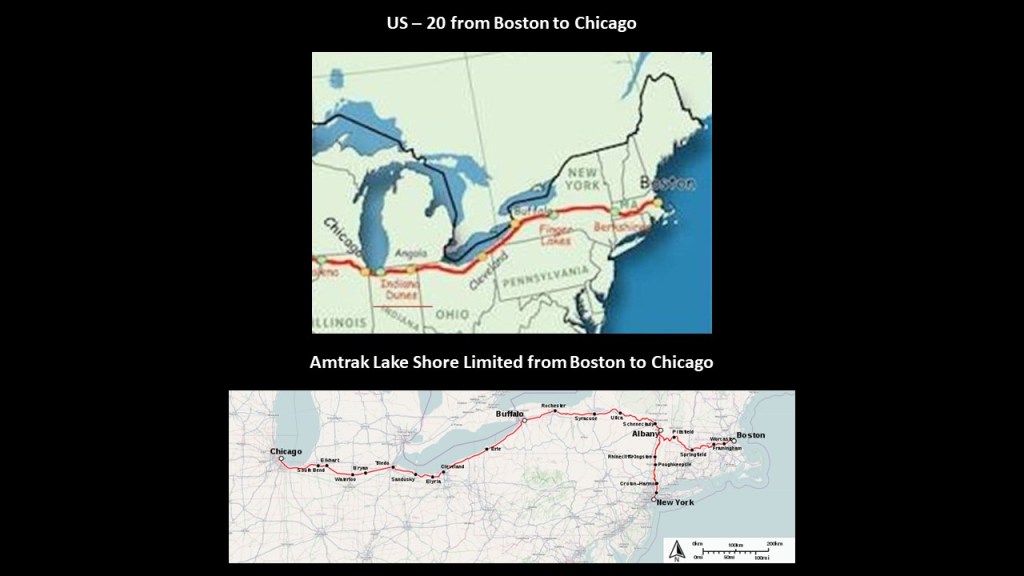

Interestingly, the “American Discovery Trail” includes the the Indiana Dunes Discovery Trail on the Southern Shore of Lake Michigan, which is called one of the most biodiverse areas in the United States, and includes sand dunes and wetlands, including bogs, existing right next to each other in the same location, and both are beside railroad tracks, circled on the bottom right.

The South Shore Line runs in ths part of Indiana starting in South Bend, and goes between Michigan City just to the east of the Indiana Dunes, to Gary, Indiana, located just to the west of the Indiana Dunes, on its way to Chicago, Illinois.

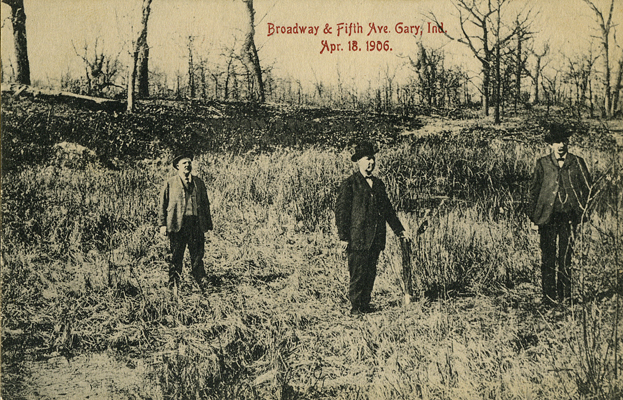

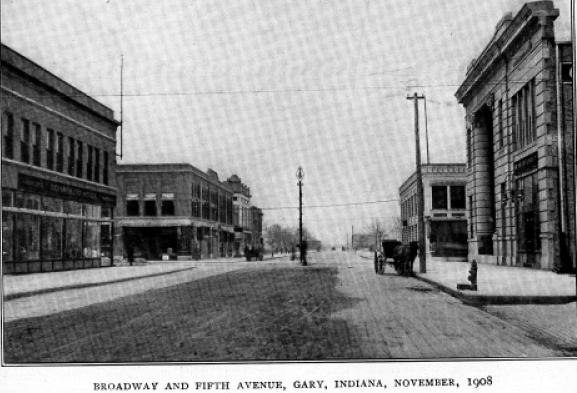

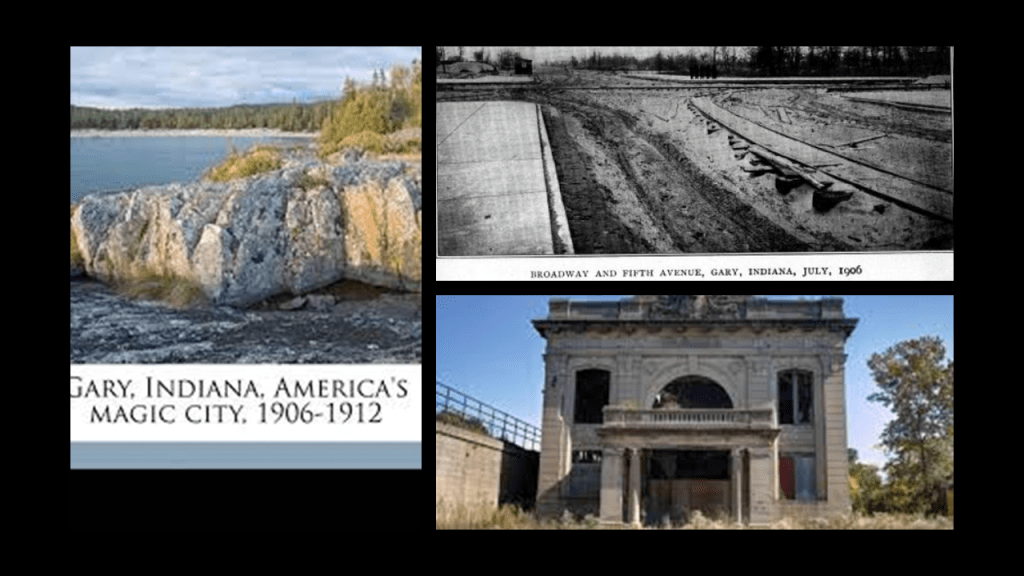

In June of 1906, the location of what became the city of Gary, about 26-miles, or 42-kilometers, east of Chicago, Illinois, was a wasteland of drifting sand and patches of scrub oak.

No one lived there, and there was no agricultural value to the land.

Yet, three or four railroads passed through the area and the Grand Calumet River wound its way around sand dunes to get to Lake Michigan.

It was in June of 1906 that the first shovelful of sand was turned for the creation of the new steel town of Gary.

Laborers were housed in tents and shacks, and were digging trenches as very little work was being done above-ground.

By 1908, lo-and-behold, the city of Gary had taken on its shape and form!

Gary was heralded as a “Magic City,” having been transformed from sand dunes in record time!

It was established to be the “company town” for U. S. Steel, and became home to the largest steel mill complex in the world, with its operation starting in June of 1908, only two-years after the first shovelful of sand was turned at this location.

U. S. Steel is still the largest employer in Gary, and is still a major steel producer, but with a significantly reduced workforce due to the increase in overseas competitiveness in the steel industry over the years.

Actually, after the “magic” of its beginnings, Gary has been in decline for years, with population loss leading to abandonment of much of the city, unemployment and decaying infrastructure.

Now I am going to take a look at White Sulphur Springs, West Virginia, which is roughly 24-miles, or 39-kilometers, to the southeast of the bogs at Cranberry Glades.

White Sulphur Springs was said to have been settled in 1750, and developed as a health spa in the 1770s, as the story goes after a woman was healed of rheumatism after bathing in the springs, and calls itself “America’s Resort since 1778.”

The springs are on the grounds of the Greenbrier Hotel, which was said to have been built by the Chesapeake & Ohio Railroad Company in 1913.

Even today, the same Amtrak Cardinal Line that runs through the New River Gorge has a station at White Sulphur Springs.

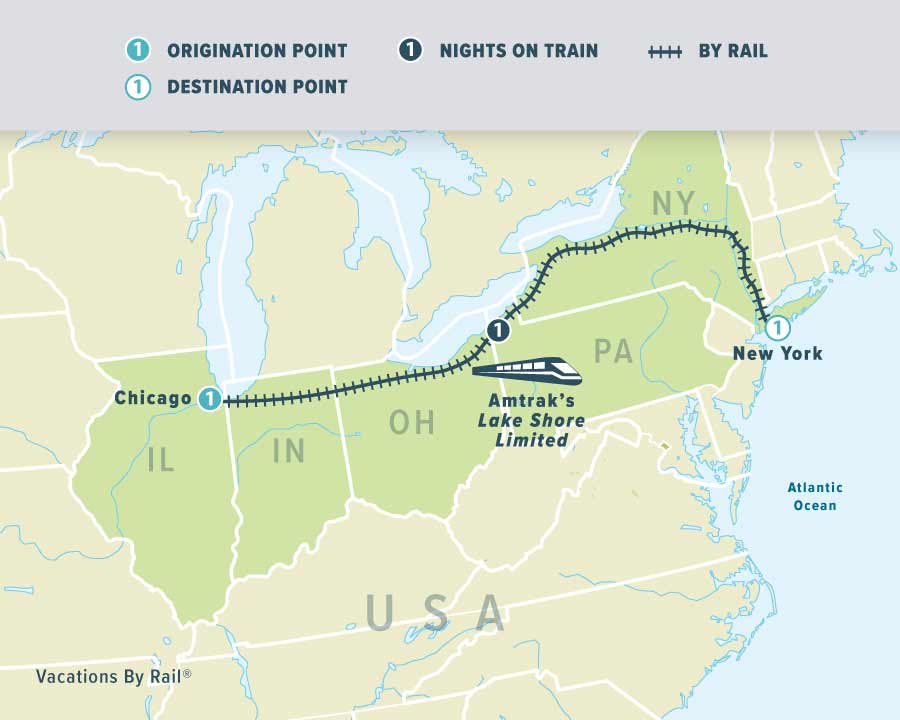

Today’s Amtrak Cardinal Line runs between New York and Chicago, by way of Washington, DC; through White Sulphur Springs, Cincinnati, and Indianapolis, on its meandering route.

The Amtrak Cardinal Line was once a part of, among others, the Chesapeake and Ohio Railway.

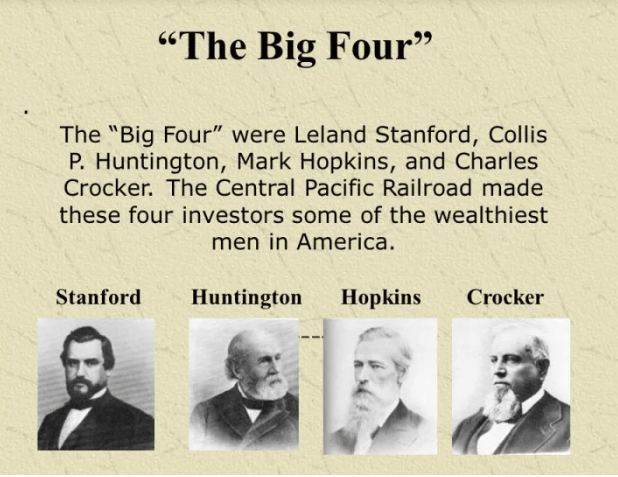

It was formed in 1869 from several smaller Virginia Railroads under the guidance of of Collis P. Huntington, in order to connect the coal reserves of West Virginia with the new coal piers that were built in Hampton Roads and Newport News, Virginia, and first opened in 1873, forging a rail link to places like Chicago in the Midwest.

The city of Huntington in West Virginia was named for him.

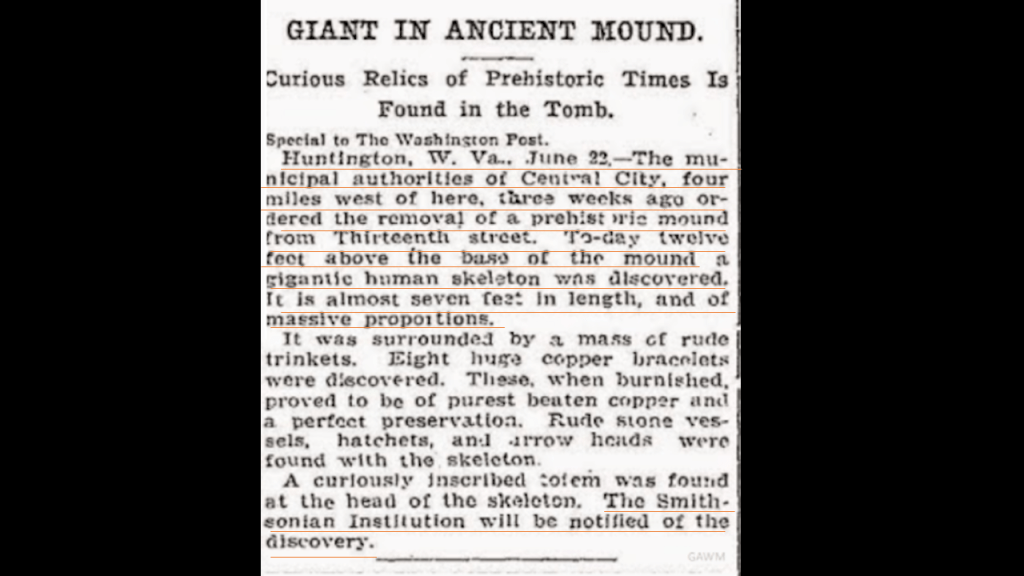

Aaron sent me this newspaper clip about an almost 7-foot-, or 2-meter-, long skeleton, of massaive proportions, that was found 12-feet, or almost 4-meters, above a prehistoric mound that was ordered to be removed, in a town just four-miles, or 6-kilometers, west of Huntington.

The article states at the end that “the Smithsonian Institution will be notified of the discovery.”

The Smithsonian Institution was established in August of 1846, and was created by the United States government for the stated purpose of the “increase and diffusion of knowledge.”

Nicknamed the “Nation’s Attic,” it has an estimated 154-million items in its holdings, across numerous facilities like museums, libraries, and research centers, and is the largest such complex in the world.

The Smithsonian Castle was the first building of the Smithsonian Institution, and said to have been built on the National Mall in Washington, DC, between 1849 and 1855.

It is interesting to note that researchers have long suspected the Smithsonian to have played a role in the cover-up of giants.

Back in the day, giant skeletons were displayed in public places and mentioned in newspaper articles, but all that went away

On the one-hand, there are reports that the Smithsonian admitted to the destruction of thousands of giant human skeletons in the early 1900 as the result of a U. S. Supreme Court ruling, and on the other hand, there are fact-checkers vigorously debunking this as a satirical claim and false.

Why is there such a contradiction of information, and vehement denial on the subject of giant skeletons, when there were historical records of their existence?

This is a good place to revisit on the subject of giant skeletons once again.

First, here is another publication clipping sent to me by Aaron on the subject of giants.

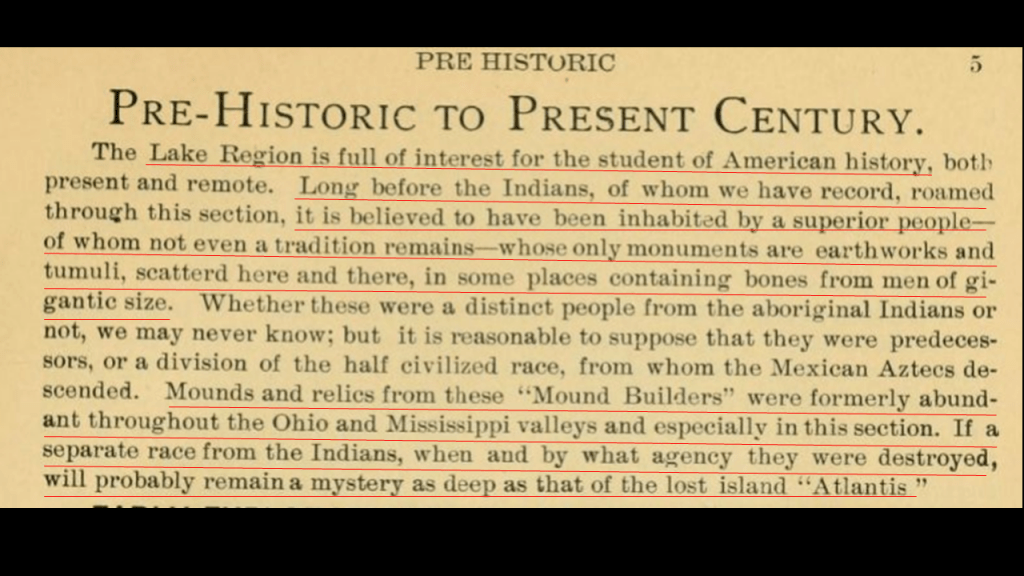

Talking about the Great Lake Region, it says “Long Before the Indians…it is believed to have been inhabited by a superior people – of whom not even a tradition remans – whose only monuments are earthworks and tumuli (another word for burial mounds), scattered here and there, in some places containing bones from men of gigantic size.”

It goes on to say further “Mounds and relics from these “Mound Builders” were formerly abundant throughout the Ohio and Mississippi Valleys, especially in this section. If a separate race from the Indians, when and by what agency they were destroyed will probably remain a mystery as deep as that of the lost island “Atlantis.”

So this acknowledges the presence of giants here who were Mound Builders, but shrouds what happened to them in mystery, just like the lost Atlantis, saying we don’t know who they were, or really anything about them, except that they were a superior people.

Along with the tallest skeleton by far being 18-feet, or 5.5 meters, -tall at West Hickory in Pennsylvania, seen earlier in this post, of the ten featured on this graphic, three are in the vicinity of where we have been looking at around Huntington, West, Virginia.

Number 10 on the list was found at the Great Serpent Mound, at 7-feet, or a little over 2-meters, -tall; #9 at Cresap Mound in West Virginia at 7-feet, 2-inches, still a little over 2 -meters, – tall; and #6 at Miamisburg, Ohio at a little over 8-feet, or 2.5-meters, -tall.

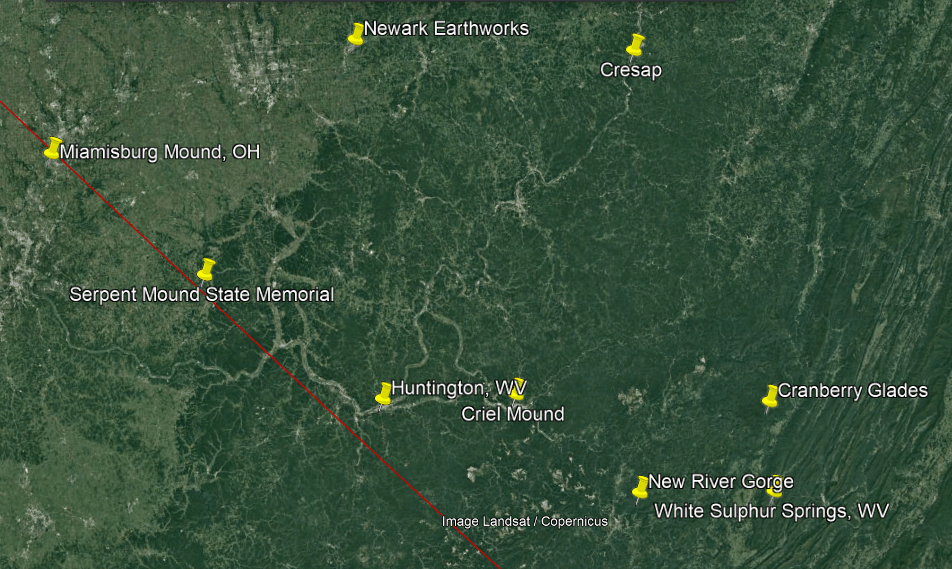

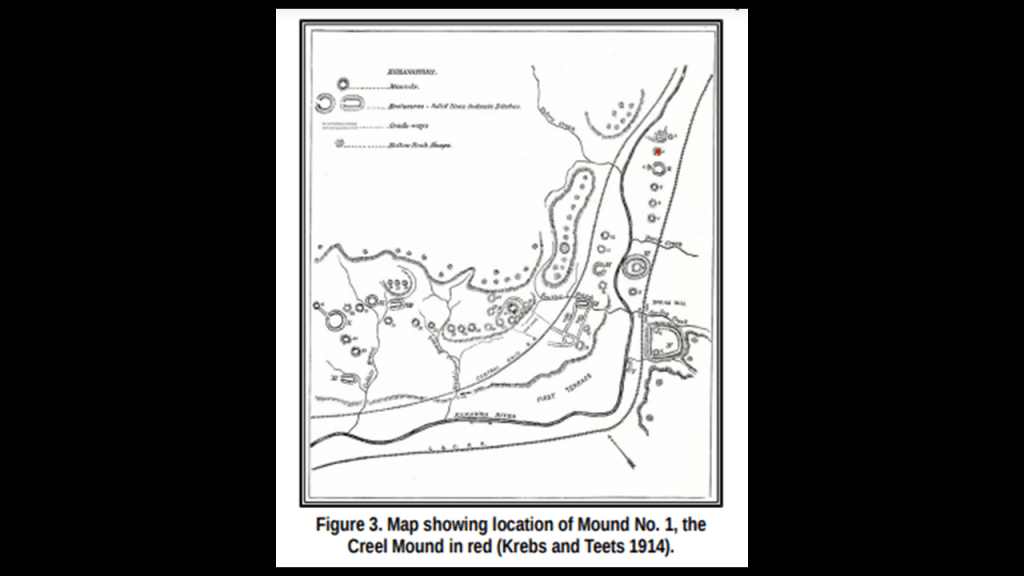

Criel Mound in South Charleston West Virginia, a short distance as the crow flies of of 41-miles, or 66-kilometers, from Huntington.

It was said to have been levelled in 1840 to create a judge’s stand for horse-races that were run around the base of the mound at the time.

We are told it was excavated between 1883 and 1884, and that thirteen-skeletons were found all together, with one of them being documented as having had a height of almost 7-feet, or 2-meters.

The Criel Mound is one of the few surviving mounds of the Kanawha Valley Mounds.

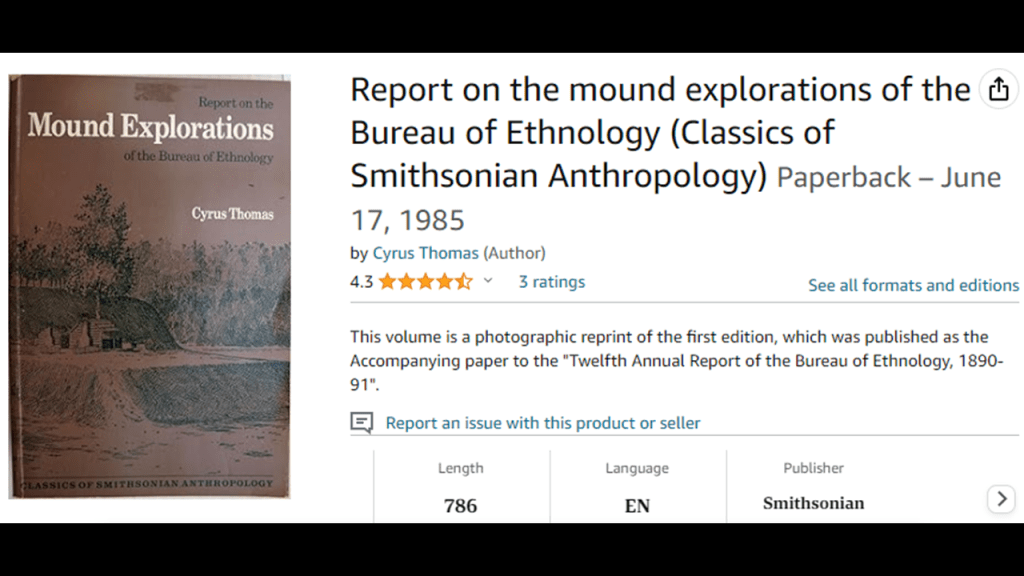

The area extended along the upper terraces of the Kanawha River floodplain for 8-miles, or 13-kilometers, and consisted of 50 mounds and 8 – 10 circular earthworks, as reported by Cyrus Thomas, a prominent ethnologist of the late 19th-century employed by the Smithsonian Institution’s “Bureau of Ethnology,” best known for his work on American mounds.

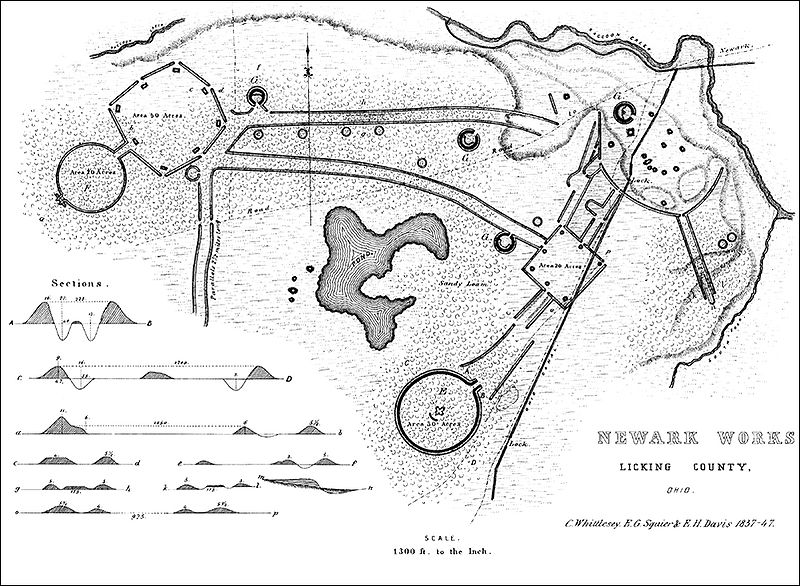

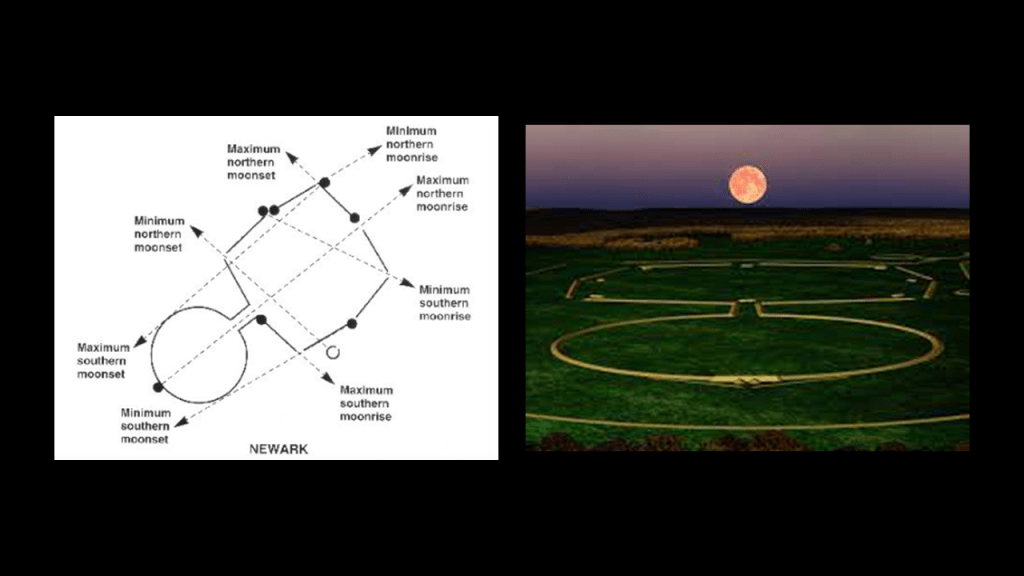

The Newark Earthworks in Ohio are roughly mid-way between Miamisburg, Ohio, and Cresap, West Virginia.

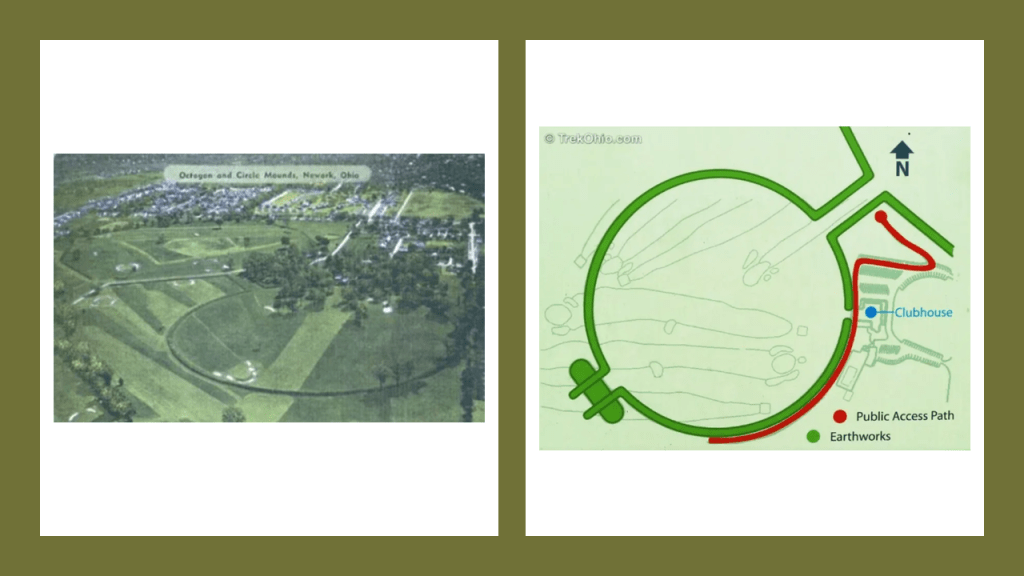

Consisting of three sections of earthworks – the Great Circle Earthworks; the Octagon and Circle Earthworks; and the Wright Earthworks – this complex contains the largest earthen enclosures in the world at about 3,000-acres, or 1,214-hectares.

We see the same precise geometry and archeoastronomy in these earthworks in North America that we see in other countries, like Great Britain.

Yet, this fact didn’t stop the development of a golf course on the Octagon & Circle Earthworks in the early 20th-century.

These earthworks come into play on eleven of the holes of the Moundbuilders Country Club.

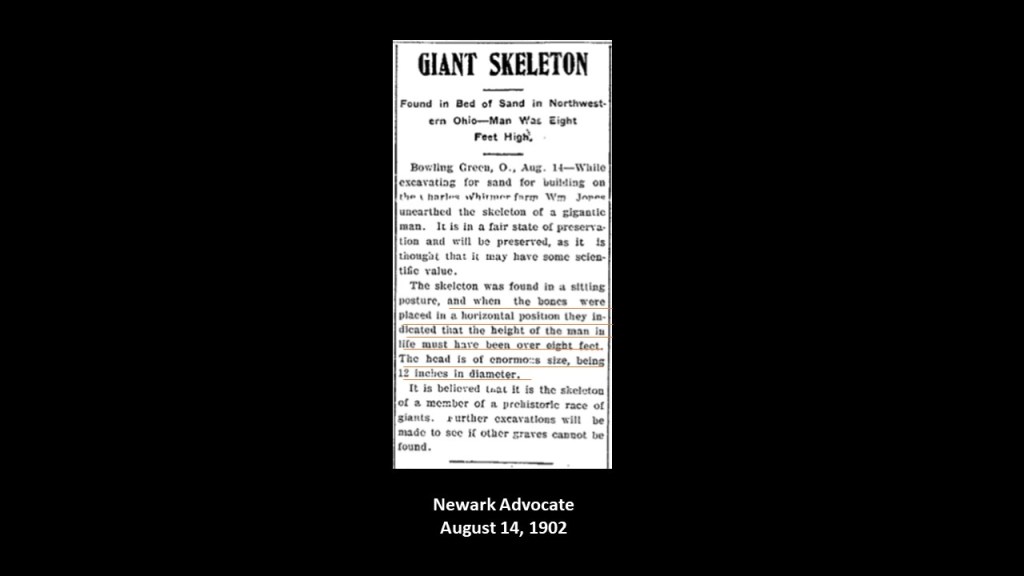

I found this newspaper clipping from the Newark Advocate in 1902 in my past research describing a giant skeleton that was found in Bowling Green in northwestern Ohio that was over 8-feet, or 2.5-meters, -tall.

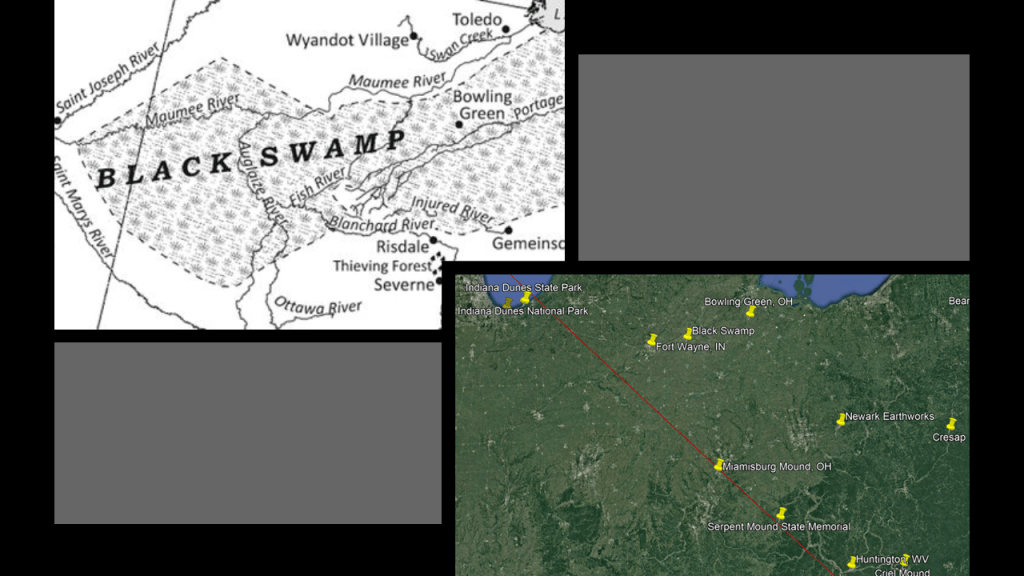

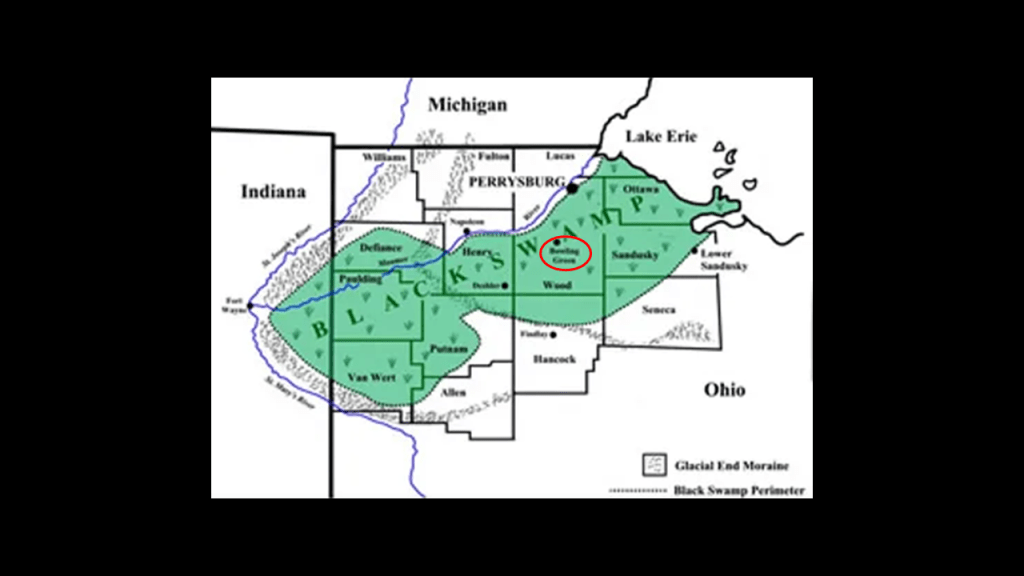

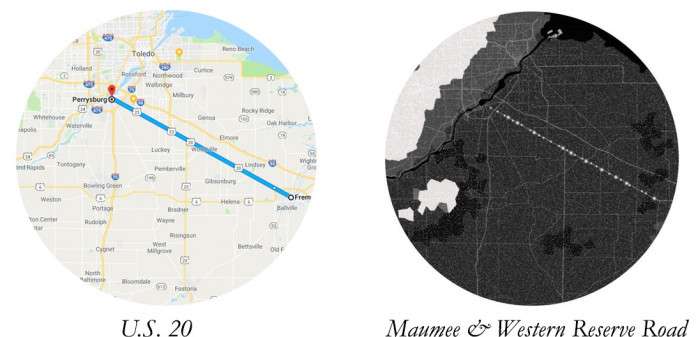

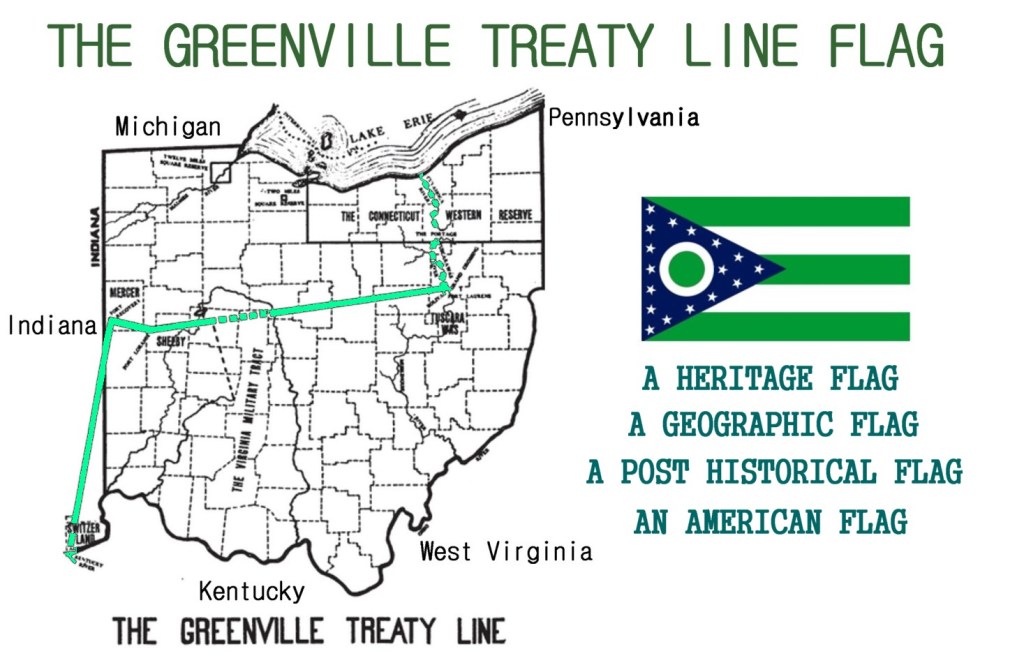

Bowling Green in Ohio is in what is called the “Great Black Swamp,” which is located between Fort Wayne in Indiana and the southern shore of Lake Erie in northwest Ohio.

The “Great Black Swamp,” and the “Indiana Dunes” on the southern shore of Lake Michigan that I mentioned previously in this post, are geographically quite close together.

Now back to Huntington, West Virginia.

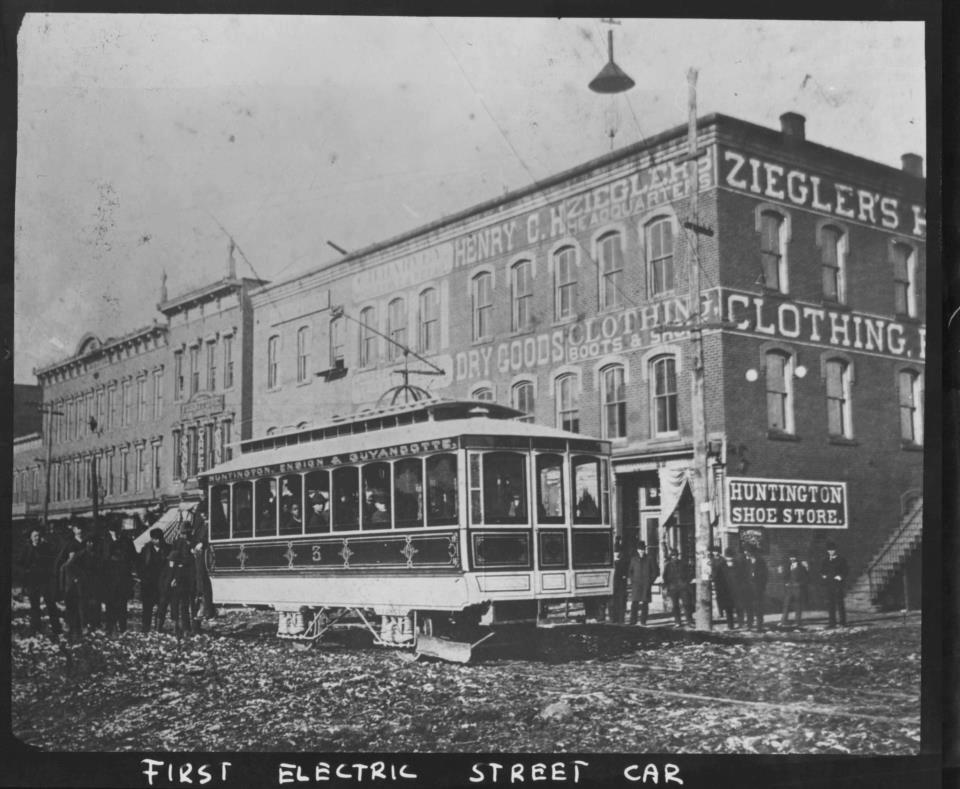

Huntington was said to be one of the first American cities to have electric streetcars, with service believed to have started around the end of 1888, and ran until the 1920s, during which time the Ohio Valley Electric Railway had organized a gas-powered bus service, which by November 1937 had completely replaced all of Huntington’s former electric streetcar lines.

Collis P. Huntington was one of the Big Four of western railroading, along with Leland Stanford, Mark Hopkins and Charles Crocker.

Then in 1888, Huntington lost control of the railroad to J. P. Morgan, an American financier and investment banker who dominated corporate finance on Wall Street during the Gilded Age between 1877 and 1900, and William K. Vanderbilt, who managed the Vanderbilt family’s railroad investments.

William K. Vanderbilt was was the grandson of Cornelius Vanderbilt, one of the richest Americans in history, who was an American magnate, and who built his family’s fortune in shipping and railroads.

The process continued on for the C & O Railroad to consolidate and merge railroads, and, for example, to gain access to productive coal fields throughout the region, through the 1920s.

Anyway, back to White Sulphur Springs, and the Greenbrier Resort.

The Greenbrier Resort was at one time a Presidential getaway, with President Eisenhower the last President in office to have stayed there, with 27 presidents having stayed at the hotel before him.

The Presidents’ Cottage is a museum today.

A top-secret, super-sized underground bunker was said to have been constructed there in the 1950s during the Eisenhower Administration to serve as a relocation point for the U. S. Congress in the event of a nuclear war, but when the secret came out in 1992 in a newspaper article, it was decommissioned.

It had features like:

–A 25-ton blast door that opened with only 50-lbs of pressure

–It’s own power plant with purification equipment, and the capacity for 75,000-gallons of water storage, and 42,000-gallons of diesel fuel

–Every kind of medical care one would ever need

–Sleeping, meeting, and eating facilities for over 1,000 people.

It was kept stocked with supplies for thirty-years but never used as an emergency location.

In 1995, the government ended the lease agreement with the Greenbrier, and it was opened to the public for tours, which it offers to this day.

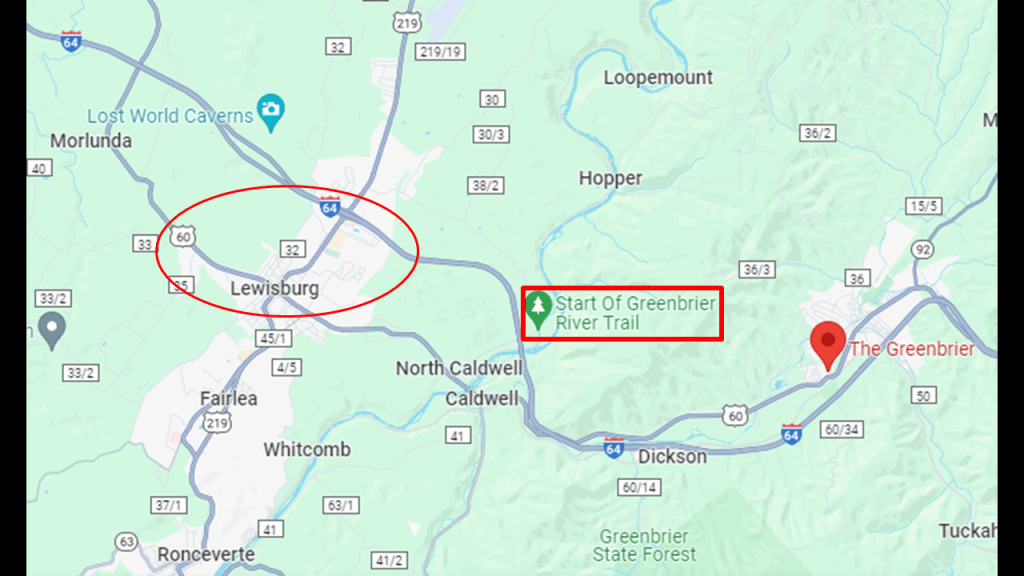

Now on to Lewisburg.

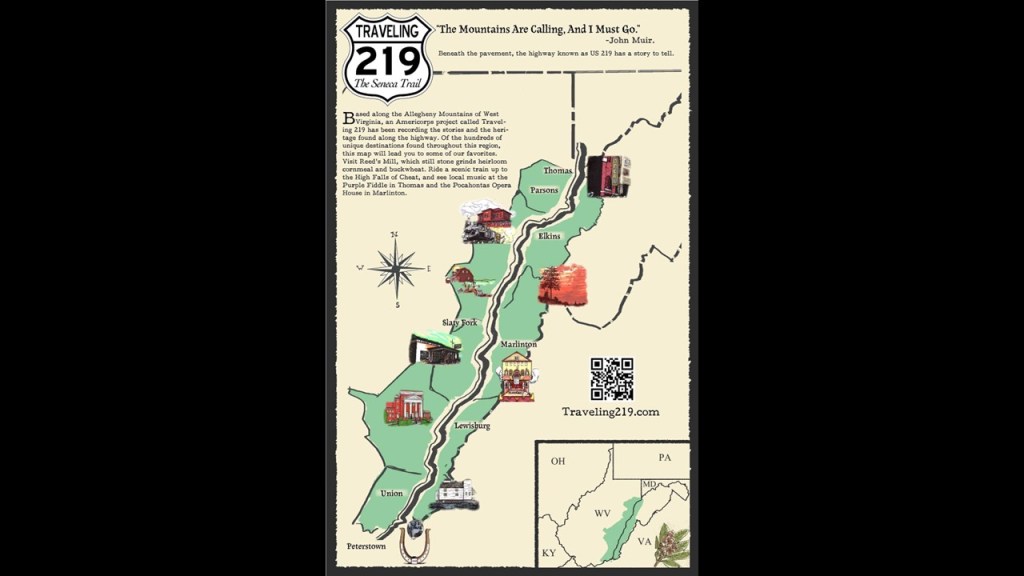

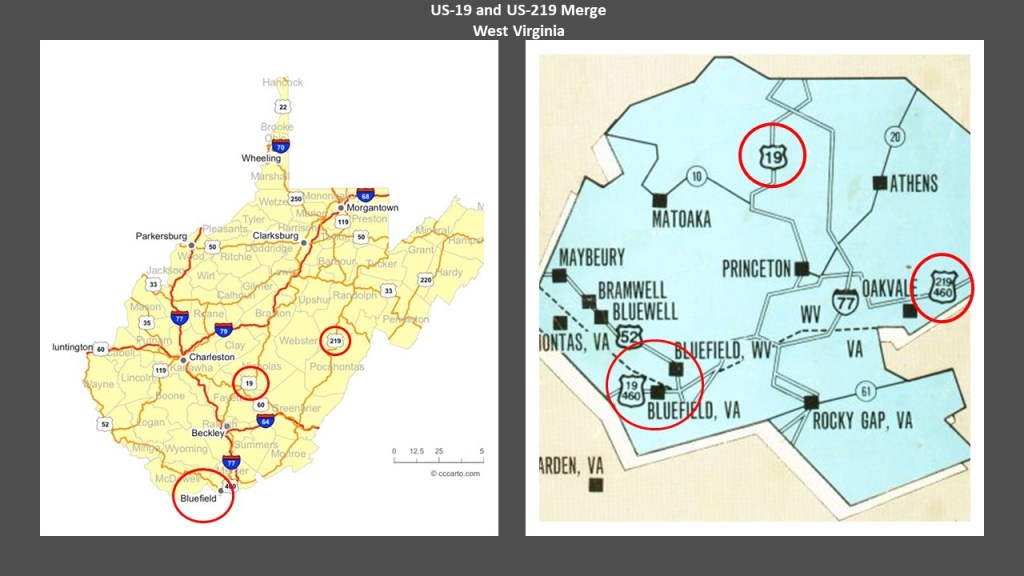

Lewisburg is located at the junction of Routes 219 and U. S. 60, and 219 and Interstate 64, and yes, the Greenbrier River Trail between the Greenbrier Resort and Lewisburg on Interstate 64 was a former railroad bed and right-of-way.

This is the same U. S. Route 219 we saw back in Pennsylvania in connection with Mahaffey Borough, which was located on U. S. Route 219, at the junction of the New York Central Railroad and the Hudson River Railroad.

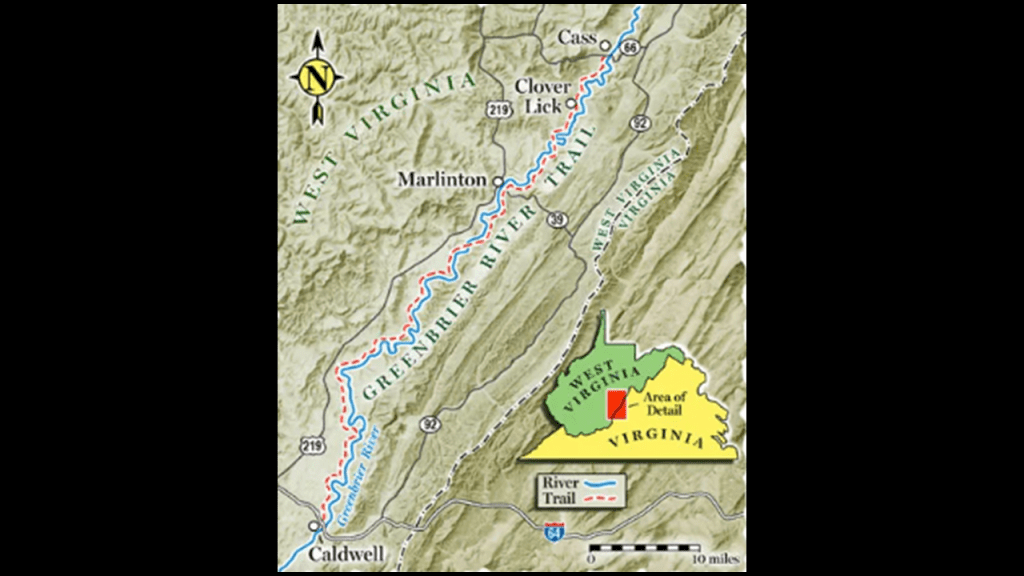

What is now the Greenbrier River Trail was gifted to the State of West Virginia in the late 1970s and opened as a recreational, multi-use trail in 1980.

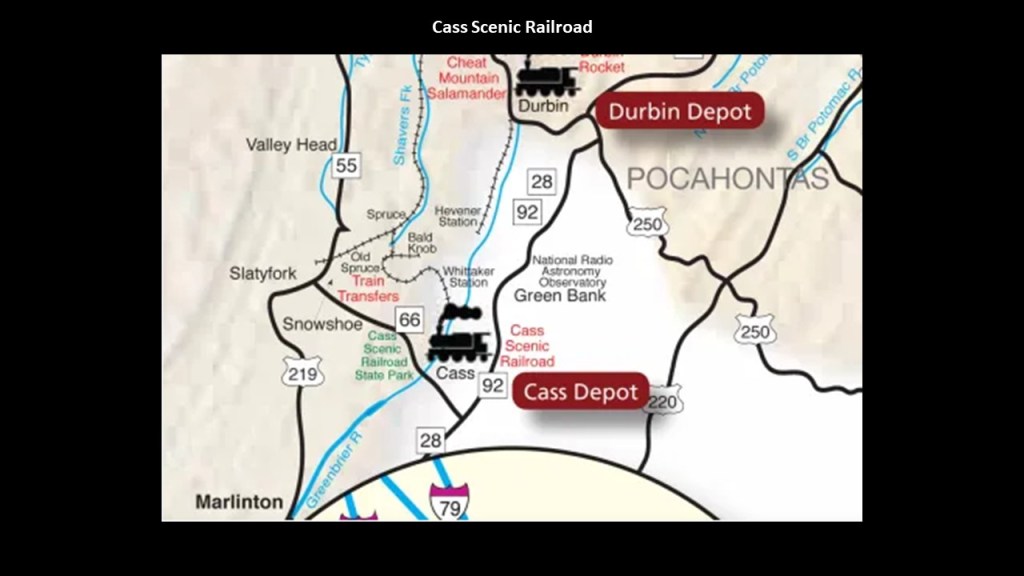

It is 78-miles, or 126-kilometers, – long and runs between North Caldwell, which is 3-miles, or 5-kilometers, east of Lewisburg on U. S. Route 60/Interstate 64,and Cass in Eastern West Virginia.

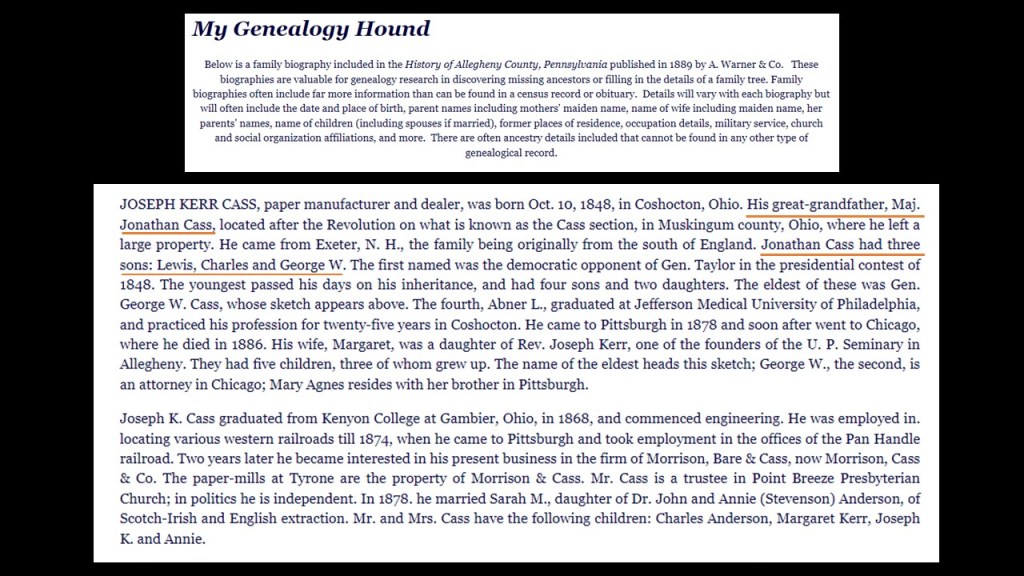

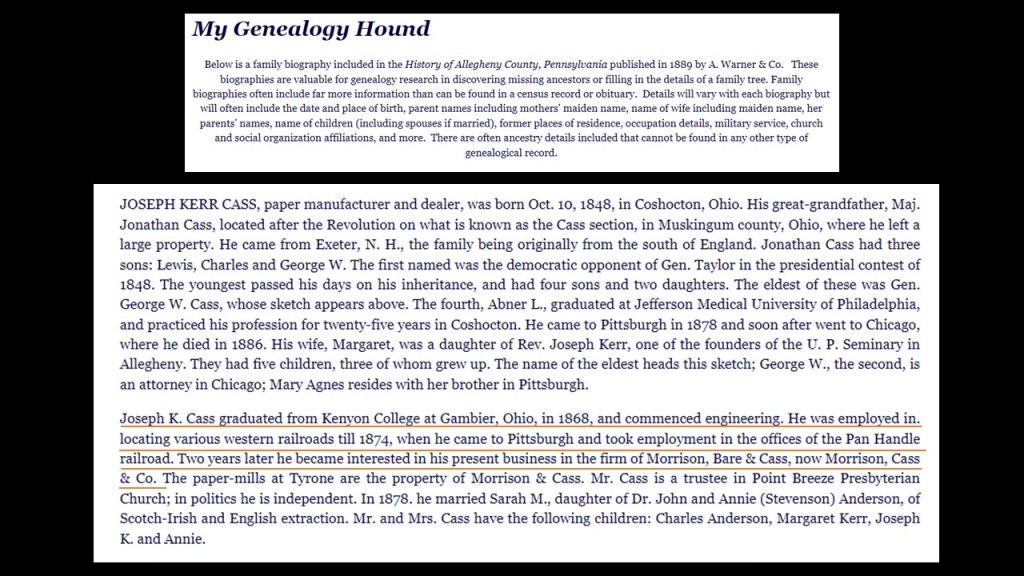

Cass, West Virginia, was founded as a company town in 1901 for the West Virginia Pulp and Paper Company, and named for Joseph Kerr Cass, the Vice-President and co-founder of the pulp and paper company.

Interestingly, this information on Joseph Kerr Cass on the “My Genealogy Hound” website from the “History of Allegheny County,” published in 1889 by A. Warner & Company, shows the following.

His great-grandfather was Revolutionary War Major Jonathan Cass, and Jonathan Cass was the father of Lewis Cass, who represents the State of Michigan in the National Statuary Hall at the U. S. Capitol.

Lewis Cass, among other things, was President Andrew Jackson’s Secretary of War from 1831 to 1836.

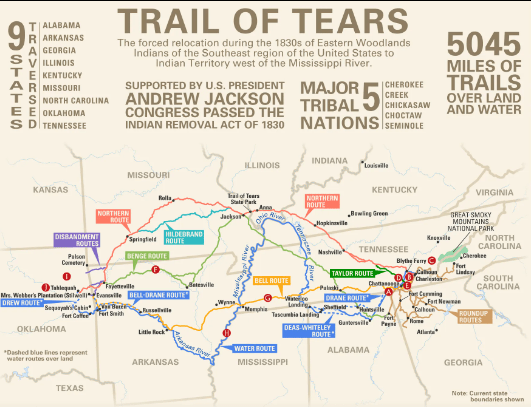

As President Jackson’s Secretary of War, Lewis Cass was central in implementing the Indian Removal policy of the Jackson administration after Congress passed the Indian Removal Act in 1830.

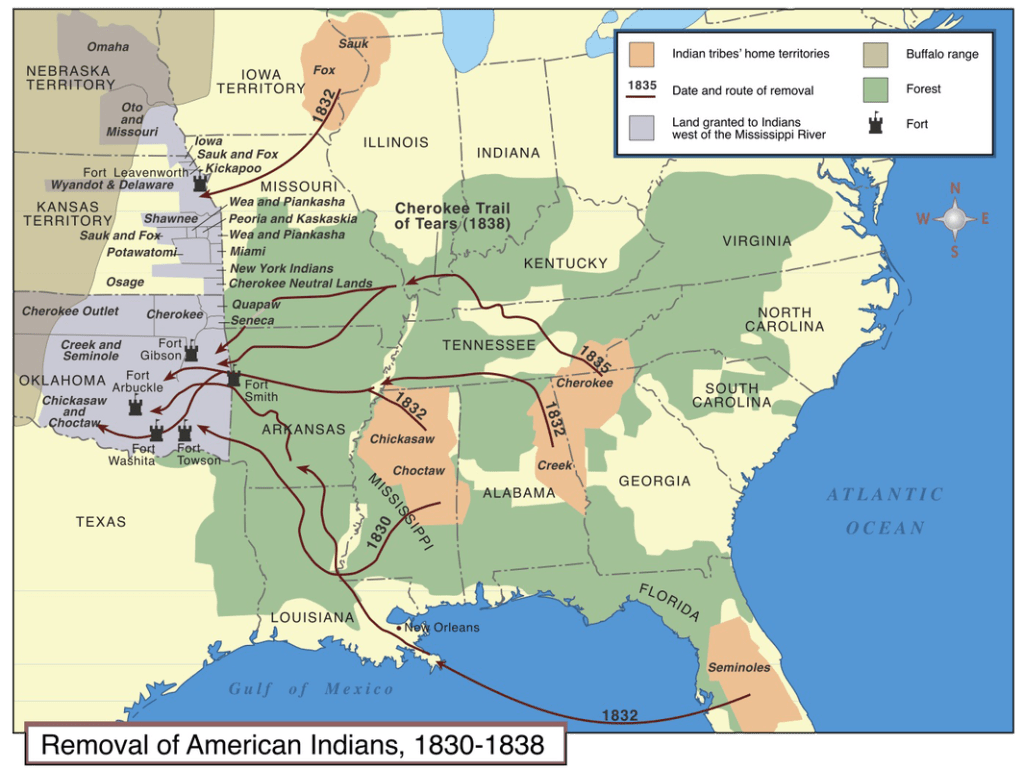

The Indian Removal Act was directed specifically at the Five Civilized Tribes of the Southeastern United States – the Cherokee, Creeks, Seminole, Chickasaw and Choctaw – though it also affected tribes in Ohio, Illinois and other areas east of the Mississippi River.

Most were forced to Indian Territory in present-day Oklahoma, Kansas, and Nebraska.

Lewis Cass was the grandfather of Lewis Cass Ledyard, a New York City lawyer, personal counsel to financier J. P. Morgan, and a President of the New York Bar Association.

Also, the information provided in from the Joseph K. Cass from the “History of Allegheny County” on the “My Genealogy Hound” website, indicated that he studied engineering in college, graduated in 1868, and was involved in “locating” various western railroads until 1874, and working for the Pan Handle Railroad in Pittsburgh, before getting into the pulp and paper mill business.

Going to break this down here.

First, Joseph Cass was involved in “locating” various western railroads until 1874.

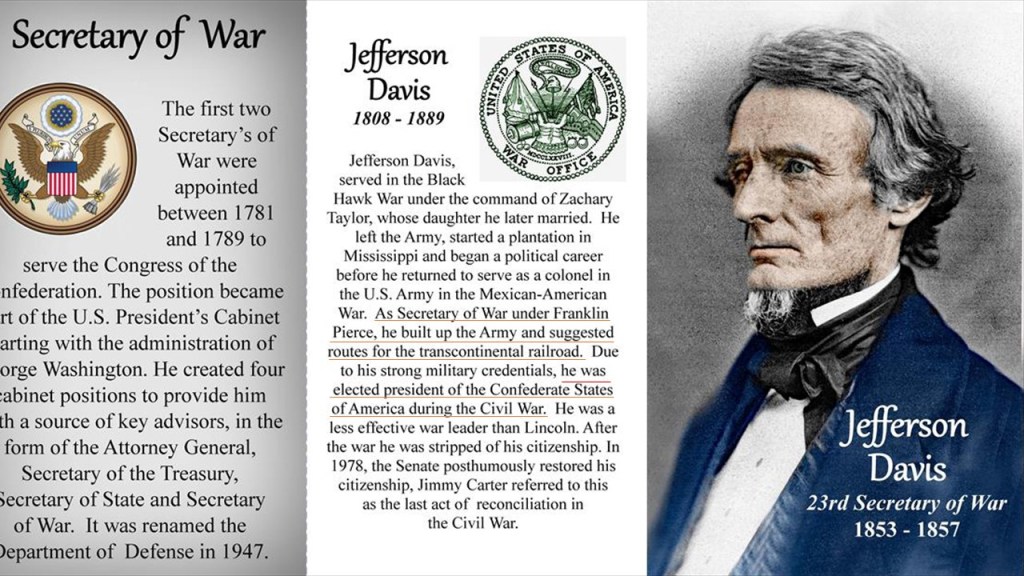

In the history we have been given, there were a number of Railroad Surveys that took place out west in the 19th-century, including the Pacific Railroad Surveys between 1853 and 1857 under the leadership of Jefferson Davis, who was the Secretary of War in the administration of President Franklin Pierce…the same Jefferson Davis who was elected as the President of the Confederacy during the Civil War.

Like Lewis Cass, the enforcer of the Indian Removal Act, Confederate President Jefferson Davis is also in the National Statuary Hall, representing the State of Mississippi.

Let’s take a look at some of the definitions of survey.

One is the perspective of the definition of survey regarding civil engineering and the activities involved in the planning and execution of surveys, gathering information related to all aspects of engineering projects, including location, in order to construct a project.

But what if another definition of survey might actually be in play here instead of what we have been told?

Perhaps more like some of the definitions shown here:

“A short descriptive summary; the act of looking or seeing or observing; considering in a comprehensive way; holding a review; and a detailed critical inspection,” and not the kind of surveying for civil engineering projects seen in the previous slide as we have been led to believe through historical omission, and for which the phrase of Joseph K. Cass having been involved in “locating” various western railroads would also apply.

What if the Railroad Surveys of the 19th-century were undertaken to explore a ruined landscape surveying, as in “looking at and observing,” everything, including pre-existing rail infrastructure in order to restore it to use once again?

What if the deserts, for example, in North America weren’t always deserts?

Next for Joseph K. Cass, from 1874 to 1876, he worked for the Pan Handle Railroad in Pittsburgh, before getting into the pulp and paper mill business.

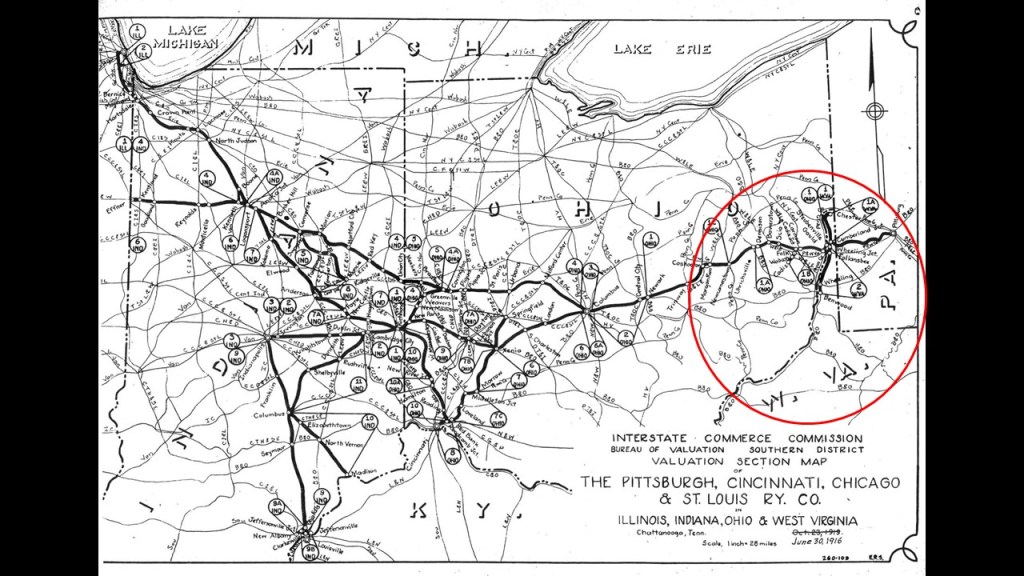

The Pan Handle Railroad refers to the name given to the main-line of the Pittsburgh, Cincinnati, Chicago, and St. Louis Railroad, and was a reference to where it crossed the Northern Panhandle of West Virginia.

We are told construction of the Pittsburgh, Cincinnati, Chicago, and St. Louis main-line began in October of 1851, and was in operation under either the name “Railway’ from September 20th of 1890 until December 31st of 1916, and under the name “Railroad,” from January 1st of 1917 until April 1st of 1956, when it was merged into the Philadelphia, Baltimore and Washington Railroad, with sections of the original route being adapted for other uses.

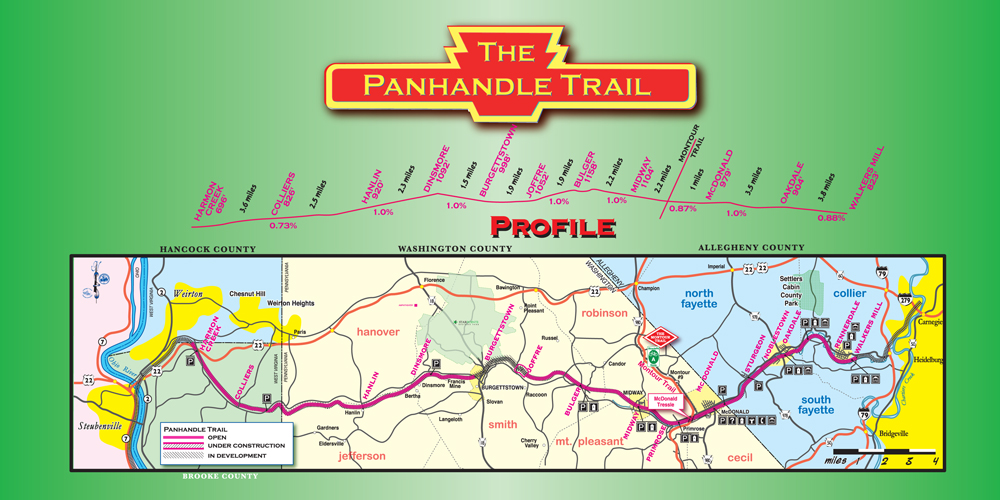

Today, the Panhandle Rail-Trail uses a 29-mile, or 47-kilometer, section of the former main-line between Pittsburgh and St. Louis.

The Panhandle Trail runs between Walkers Mill in southern Pennsylvania, to near Weirton at Harmon Creek in northern West Virginia.

Most of the town named for Joseph K. Cass, and its buildings, were bought by the State of West Virginia in 1961 after the pulp and paper mill closed in 1960, and it became the Cass Scenic Railroad State Park.

The Cass Scenic Railroad State Park continues to offer trips to Whittaker Station; the ghost town of Spruce; and Bald Knob, the highest point of the Back Allegheny Mountain in Pocahontas County.

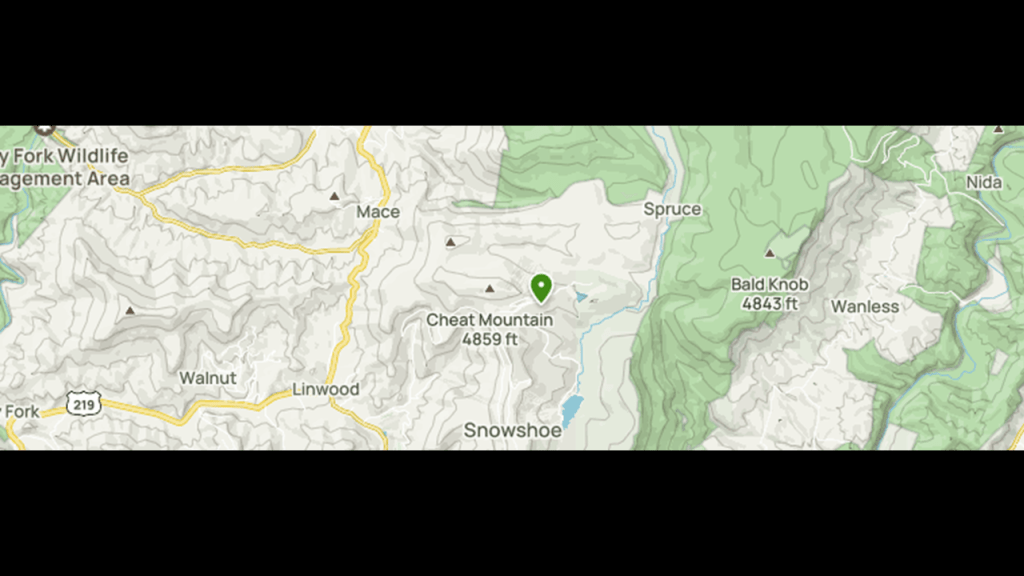

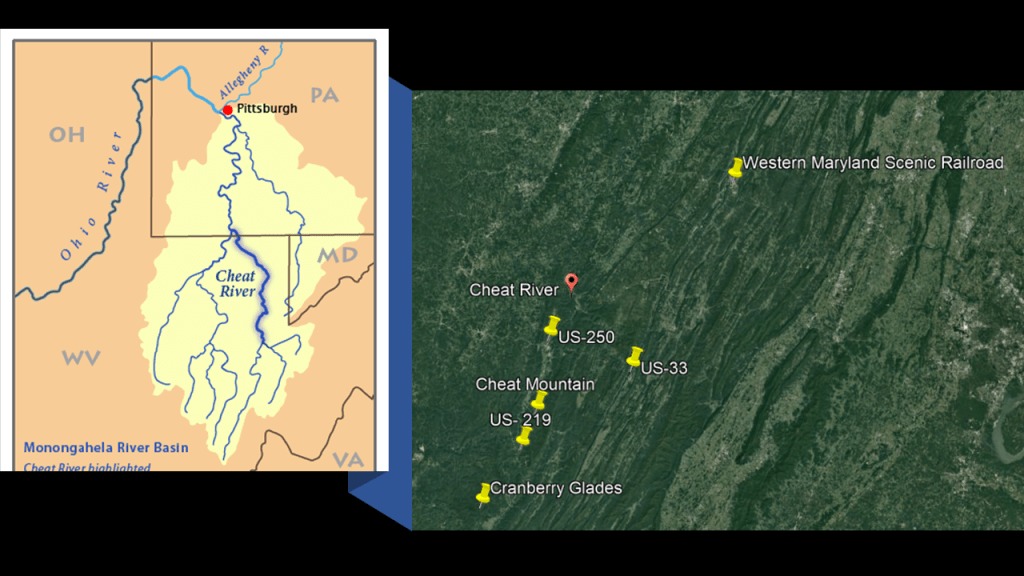

The logs for the pulp mill in Cass came from the nearby Cheat Mountain, which were brought by rail to the mill for processing until the mills closure.

Cheat Mountain, which is next to the Back Allegheny Mountain, was once the home of the largest red spruce forest south of Maine.

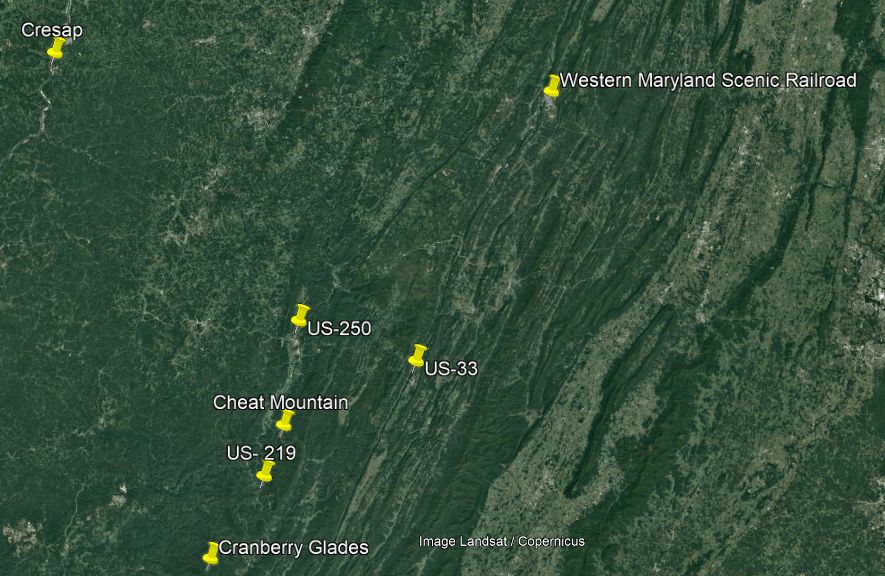

Cheat Mountain is flanked on the western side by our old friend U.S. Route 219 and on the eastern side by the Western Maryland Scenic Railroad.

East to west it is crossed by U. S. Route 33 on one side, and U. S. Route 250 on the other side.

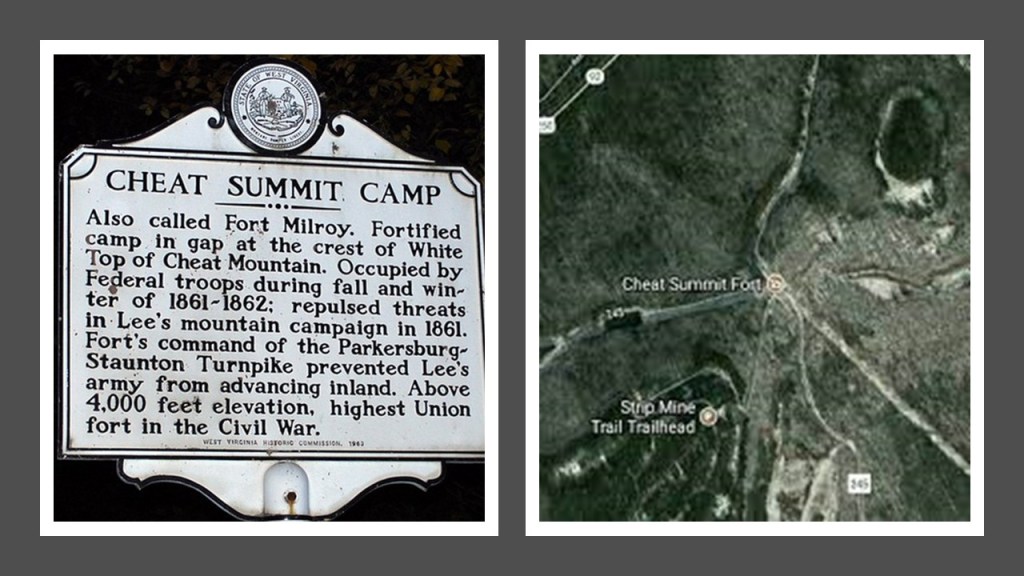

We are told that during the American Civil War, Cheat Mountain was of strategic importance during the early part of the Operations in West Virginia Campaign.

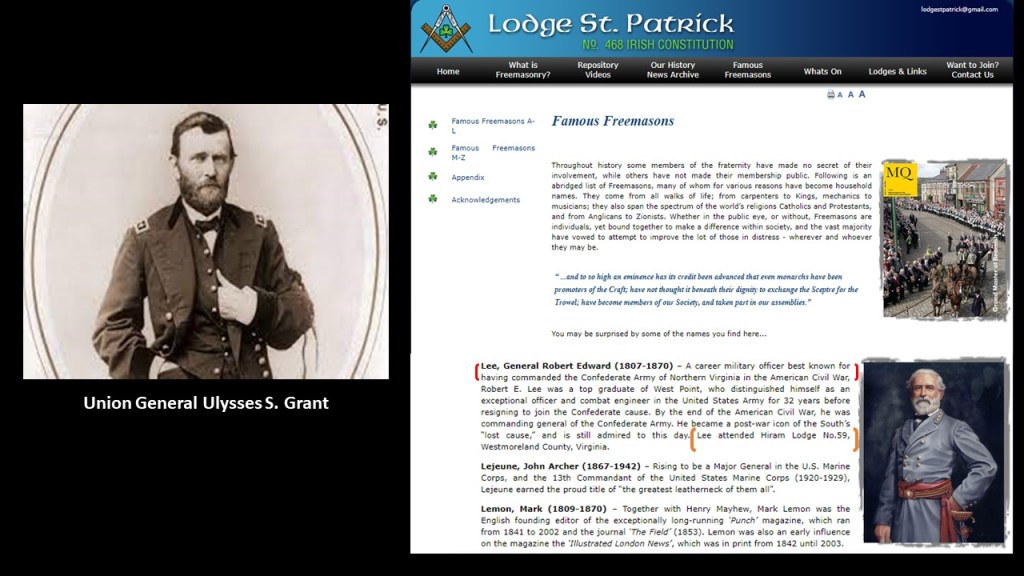

The Battle of Cheat Mountain, also known as the Battle of Cheat Summit Fort, took place between September 12th to 15th of 1861, and was the first battle that General Robert E. Lee led troops into combat.

Still a part of Virginia at the time, since what became the state of West Virginia was not formed until after the Civil War, troops under Lee sought to regain confederate territory that had been gained by the Union after Union troops had advanced into the western region of Virginia from Ohio.

The Battle of Cheat Mountain was a Confederate attempt to regain the Union occupied Fort Milroy on top of Cheat Mountain, but they were unsuccessful and “lost” the battle.

The Cheat River runs along this section of West Virginia between the state’s border with both Pennsylvania and Maryland.

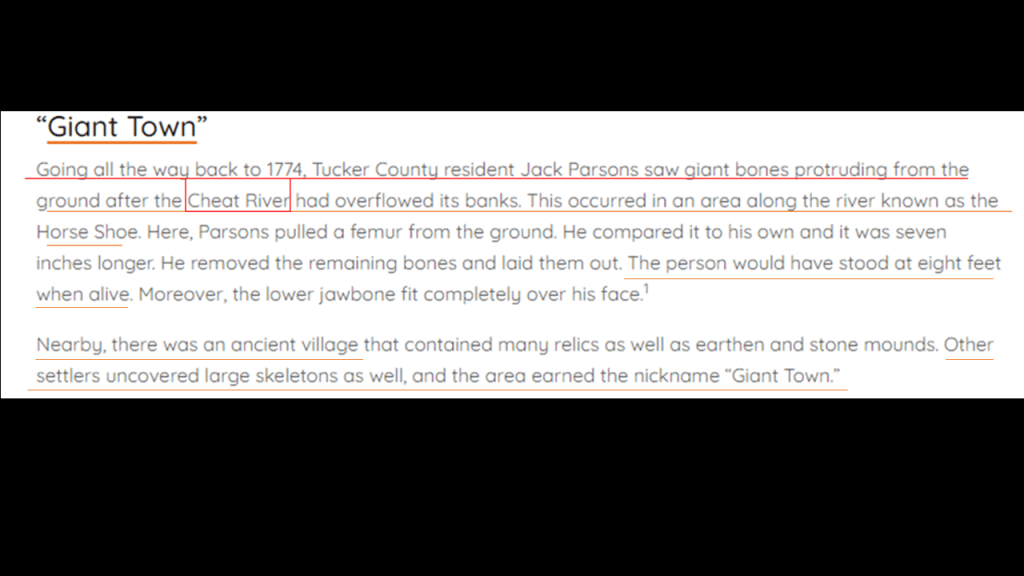

Aaron sent me this reference to giant skeletons having been uncovered in the location of the Cheat River.

The first reference was a Tucker County resident finding giant bones protruding from the ground in the area on the Cheat River known as “Horse Shoe” in 1774, that he estimated would have been from someone 8-feet, or almost 2.5-meters, -tall when he laid them out.

Also, other settlers found large-size bones nearby in what is described as an “ancient village” that had earthen and stone mounds, earning the area the nickname “Giant Town.”

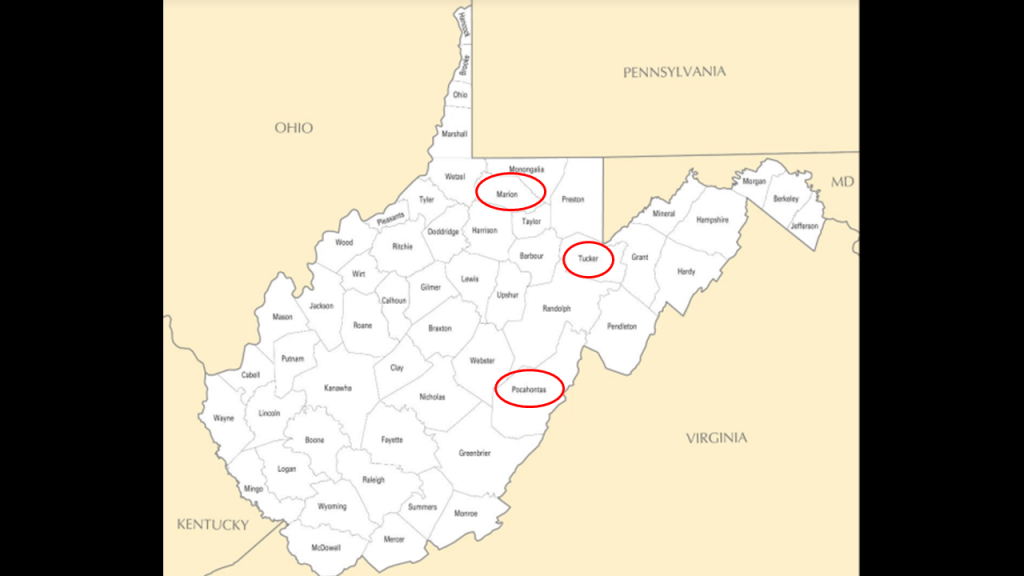

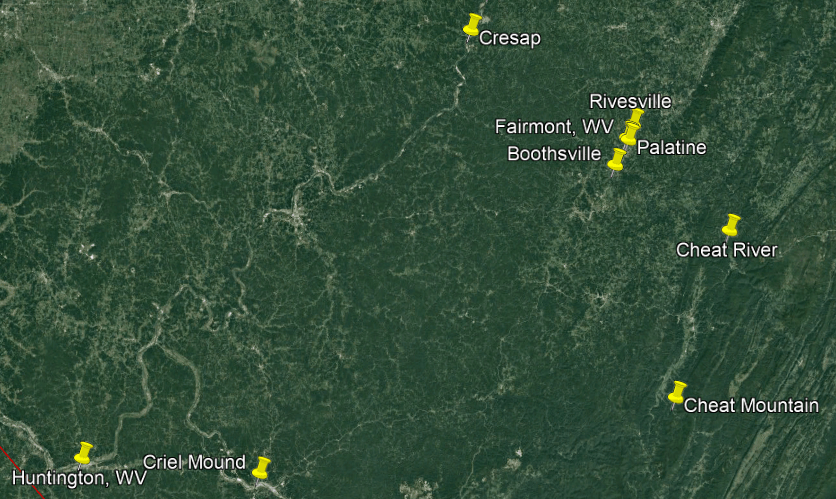

Aaron also provided me with recorded references to giant skeletons that were found in in Marion County, northwest of Tucker County, that is tucked in-between West Virginia’s borders with Ohio to the West; Pennsylvania to the North; and Maryland to the East.

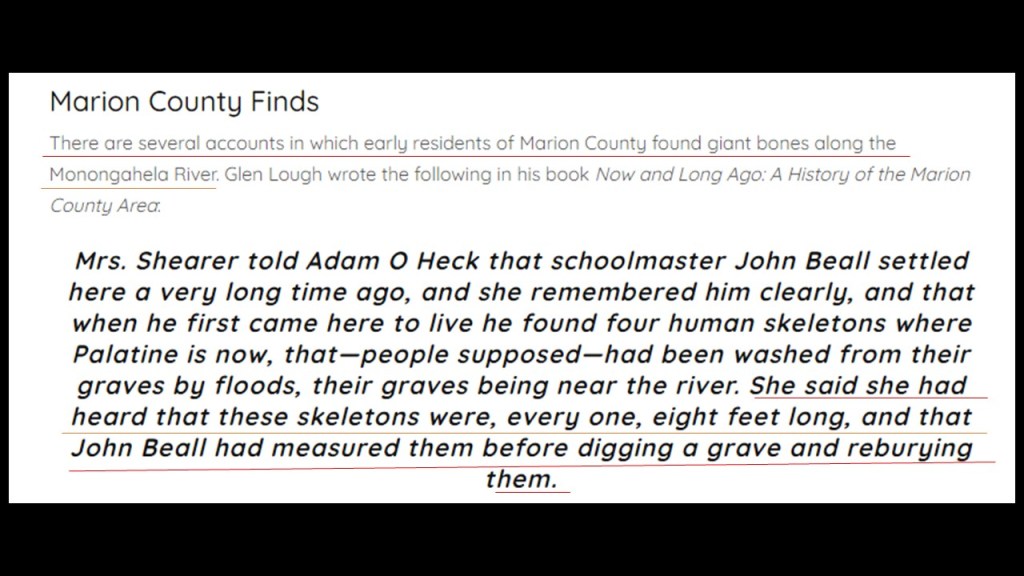

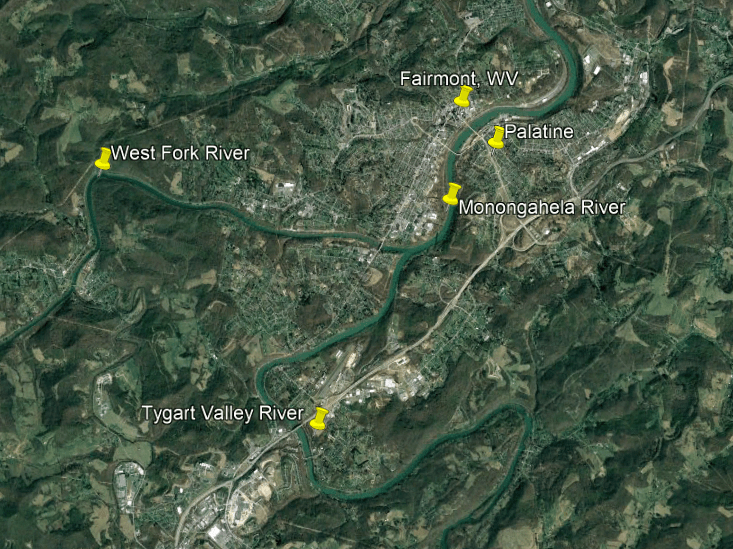

Here is an oral account that was written down that is similar to the find in Tucker County, where giant bones were found on the Monongahela River in Marion County.

A local woman reported that a schoolmaster had found four human skeletons near the river, presumably washed from their graves, where Palatine is now, and before reburying them, measured them and found that they were 8-feet, or almost 2.5-meters, -long.

Today, Palatine is part of Fairmont on the Monongahela River.

Fairmont is the seat of Marion County.

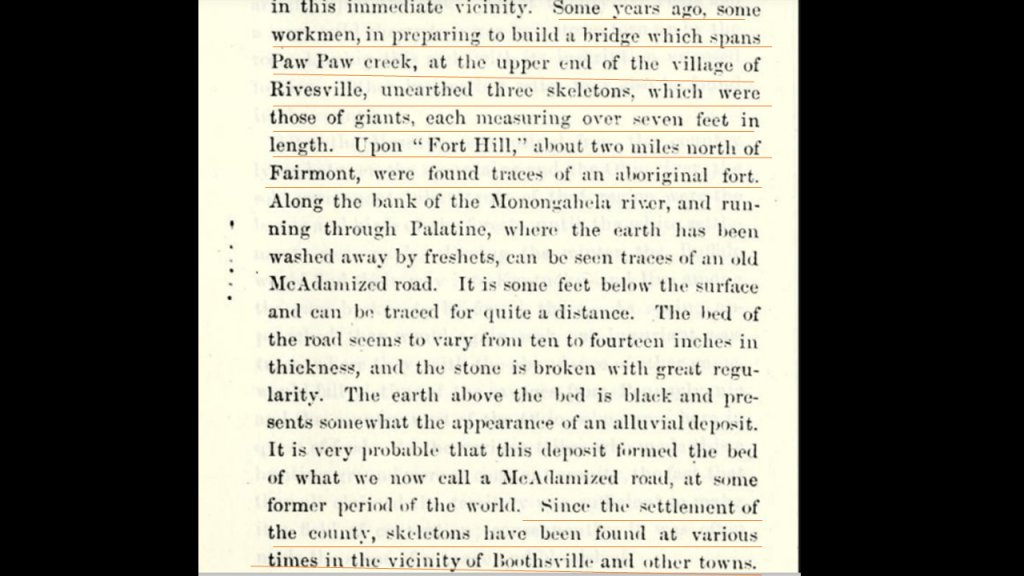

Aaron also sent me this information on p. 10 in “The History of Marion County.”

The information on this page referred to:

–Workmen preparing to build a bridge unearthed three giant skeletons, measuring over 7-feet, or 2-meters, in length, in the village of Rivesville at Paw Paw Creek;

–“Fort Hill” about 2-miles, or 3-kilometers, north of Fairmont, and traces of an aboriginal fort;

–And other skeletons having been found in the area, like around Boothsville.

These giant skeleton findings are consistent with other recorded giant skeleton finds in the surrounding area that I have already mentioned, though so far, some have been reported to have been found in mounds, and some randomly found in proximity to rivers.

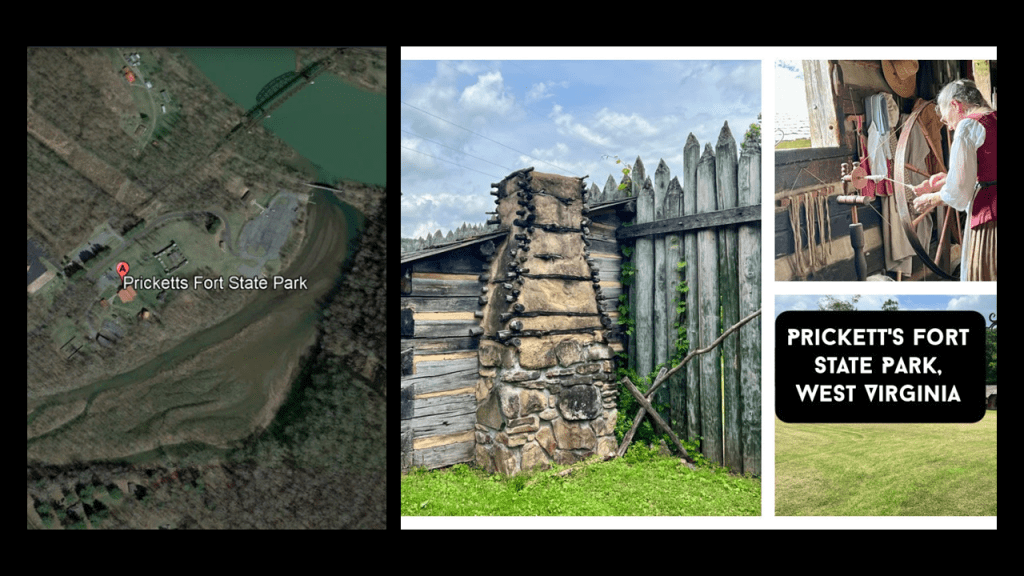

The only fort I can find any information on to speak of near Fairmont is “Pricketts Fort,” which just happens to be the same distance north of Fairmont that is referenced on the “History of Marion County” page.

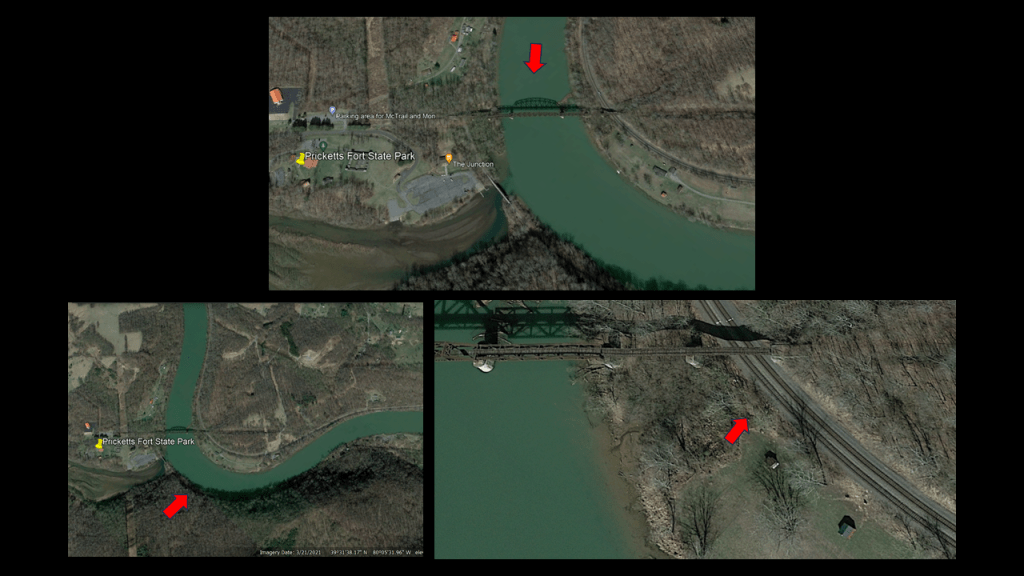

Pricketts Fort State Park is at the confluence of the Monongahela and Pricketts Creek.

What the historical narrative tells us is that it is was a reconstructed “refuge fort,” built on Jacob Pricketts’ homestead, to defend local settlers from hostile indian raids, and these days commemorates life on the Virginia frontier in the late 18th-century.

A couple of interesting things to note about the Picketts Fort location.

First is that the site of the fort is located on a river-bend, right next to an old railroad bridge that is now part of the Marion County Rail-Trail, and there are railroad tracks right next to the Monongahela River, still in use by the Fairmont Subdivision, a railroad from Grafton to Rivesville that is owned and operated by CSX Transportation on what used to be part of the B & O Railroad Mainline.

More on the area’s railroad history in a moment.

The Marion County Rail Trail runs for 2.5-miles, or 4-kilometers, from the Pricketts Fort State Park, along Pricketts Creek through rural Marion County, to Fairmont.

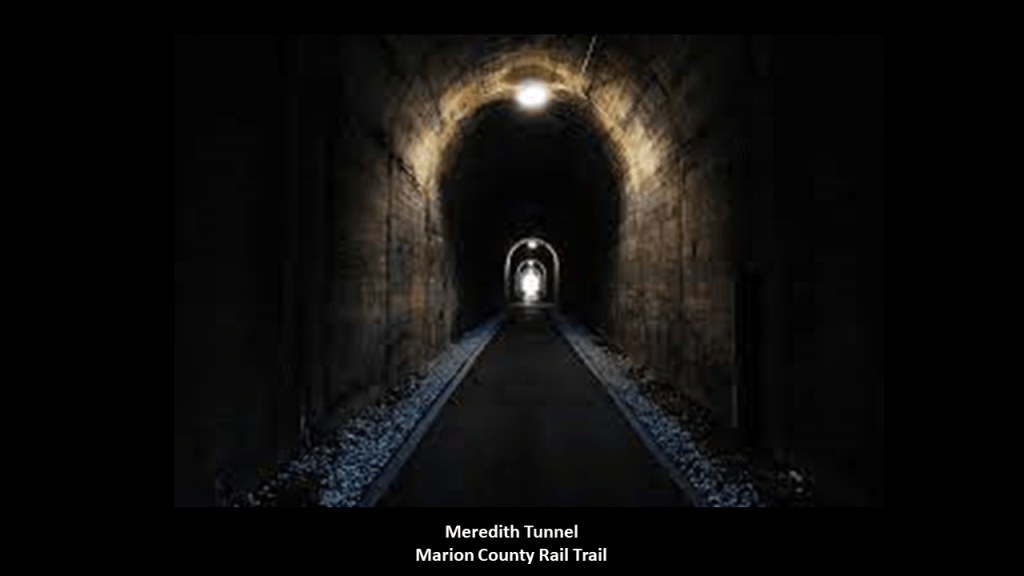

The trail’s main highlight is a 1,200-foot, or 366-meter, -long lighted tunnel, which runs under Speedway Avenue and Suncrest Boulevard. said to have been built in 1914 by the Monongahela Railroad.

The land for the trail was purchased from the railroad by the County in 1989.

Fairmont is located just above the confluence of where the West Fork and Tygart Valley Rivers meet to form the Monongahela River.

I couldn’t help but notice all the s-shaped riverbends going on around here!

So, I searched for more information on Fairmont’s railroad history and this is what I found.

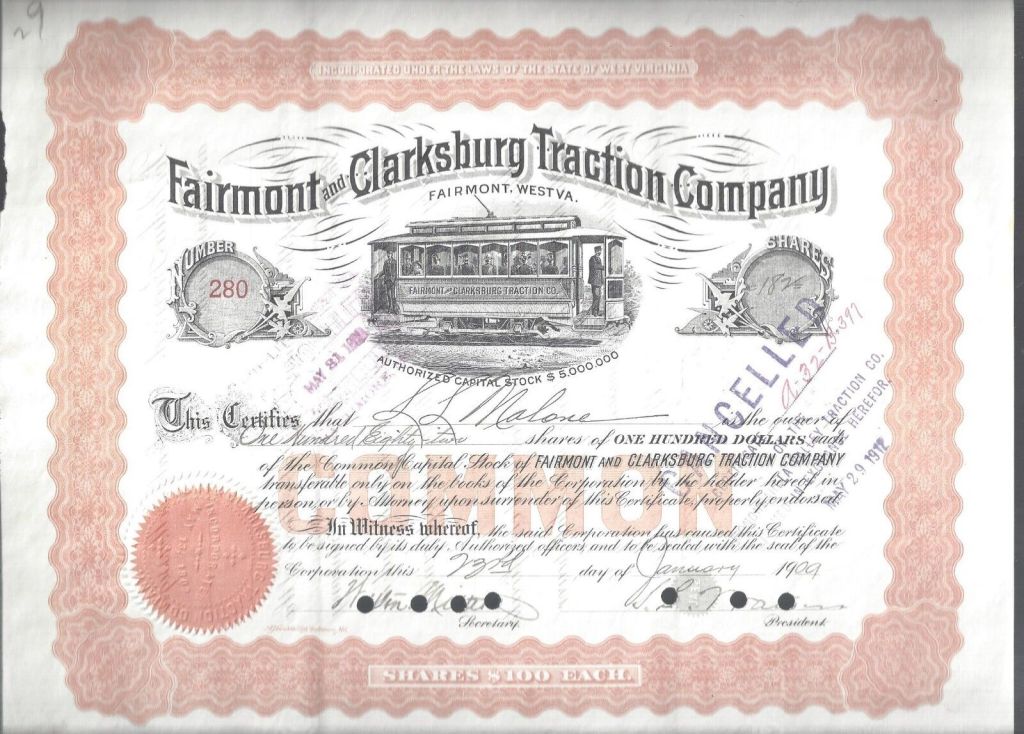

First, the Fairmont & Clarksburg Electric Railroad was an inter-urban electric streetcar system that served the Fairmont and Clarksburg areas, linked by a main-line, and connected the communities of Bridgeport, Fairview, Mannington and Weston.

It offered both passenger and freight services, and connected communities and coal camps.

It became operational in 1901.

Again, we are told that now the electric streetcar services just couldn’t compete with the advent of automobiles reducing demand for these services, and this interurban streetcar system was abandoned entirely by 1947, when the system had transitioned entirely to bus services.

This was the crossing of this interurban line at Hawkinberry Run near Rivesville, where aforementioned giant skeletons were found in Marion County.

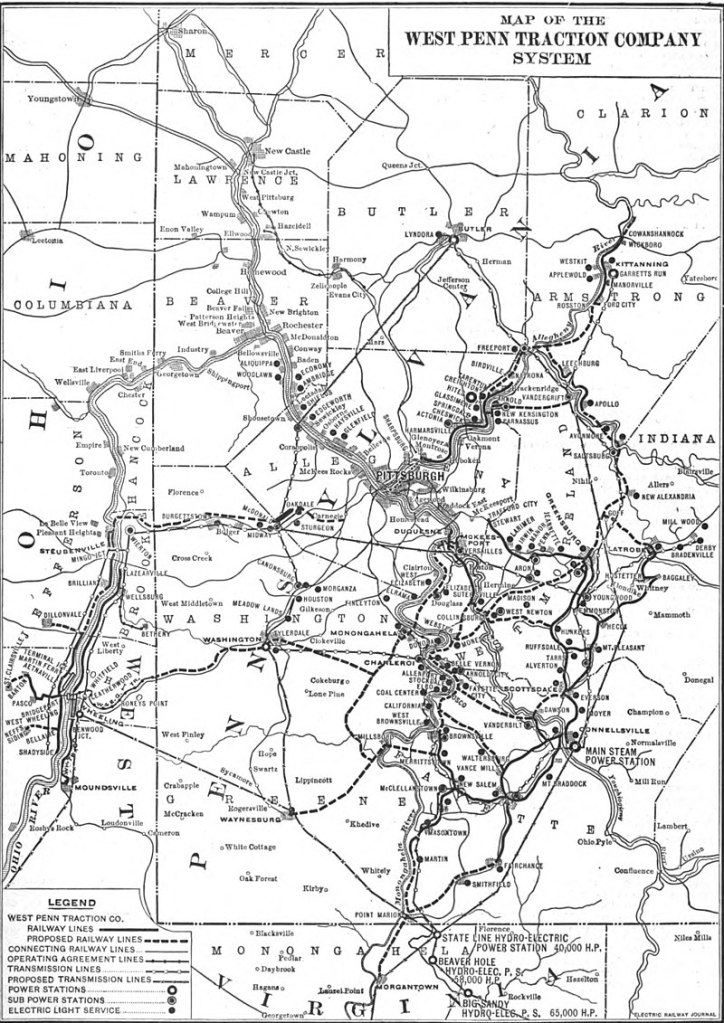

In time, the Fairmont & Clarksburg Electric Railroad was managed by the larger West Penn Railway system of electric streetcars that was headquartered in Connellsville, Pennsylvania, and was said to be part of the regions power-generation utility.

It consisted of 339-miles, or 546-kilometers, of electric streetcar track at its height.

It was operational from 1904 to 1952.

Next, the Fairmont, Morgantown & Pittsburgh Railroad once connected Fairmont to Uniontown in Pennsylvania, a distance of 56-miles, or 17-kilometers.

It became operational in 1894.

We are told the importance of this line waned as the coal mines along the route closed, and in 1953, passenger service ended.

By 1991, most of the line between Fairmont and Uniontown was abandoned, with the exception of two short stretches that are still in use today, like the one I mentioned that is owned and operated by CSX Transportation between Grafton and Rivesville.

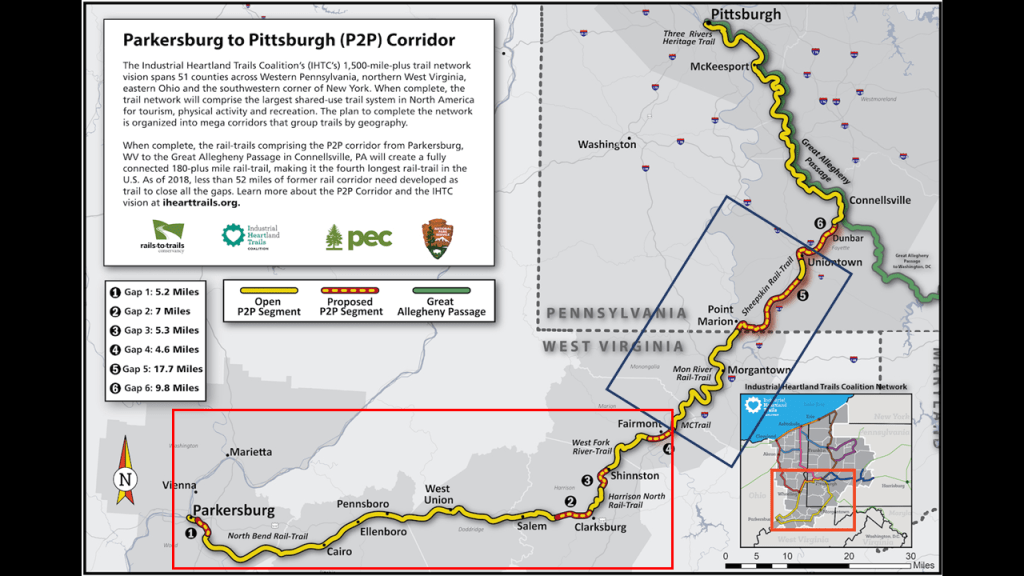

This map of the Industrial Heartland Trails Coalition’s Parkersburg to Pittsburgh (P2P) Corridor shows its plan to have a fully-connected recreational rail-to-trail between the two cities, with the proposed segments overlaid in red.

I have put a blue box around the Fairmont to Uniontown segment of the former railroad line, and a red box around the section between the West Fork River Trail, which starts just outside of Fairmont, and goes to Parkersburg, and includes the previously mentioned North Bend Rail- Trail.

Before I leave West Virginia, and head back up to Pennsylvania, there’s a few more things I would like to mention about Cranberry Glades.

Hillsboro, the town closest to Cranberry Glades, is just 30-miles, or 49-kilometers, up U. S. Route 219 from Lewisburg, and the same Route 219 that we have been seeing all along through these places in West Virginia, and Mahaffey Borough and near the area around Black Moshannon State Park in western Pennsylvania.

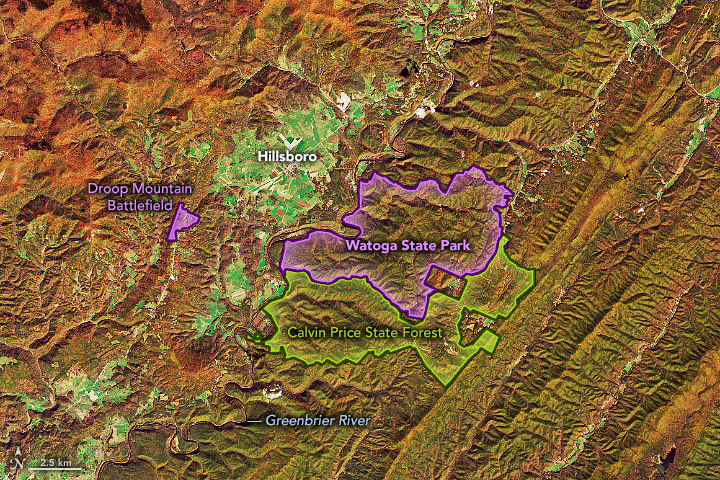

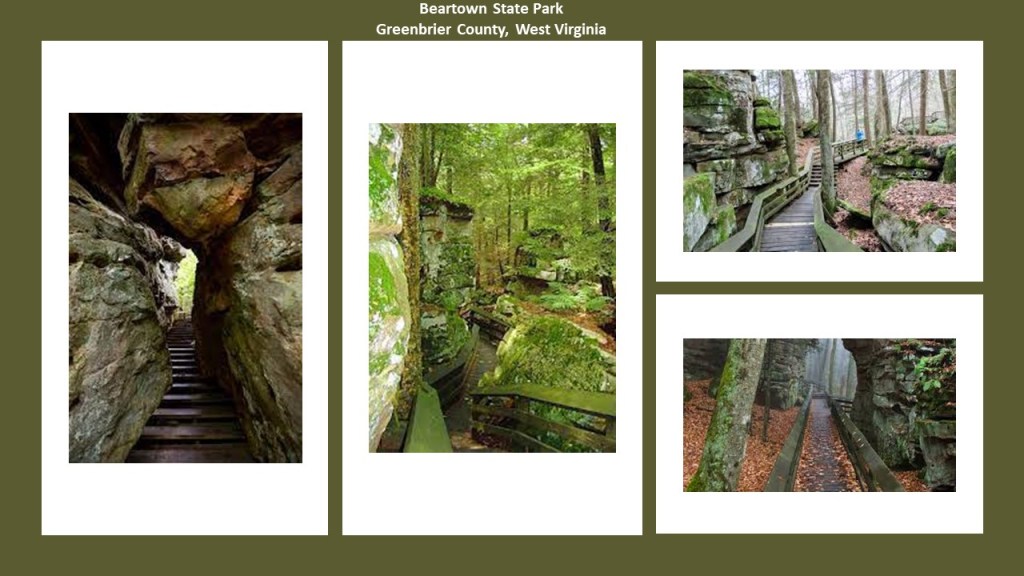

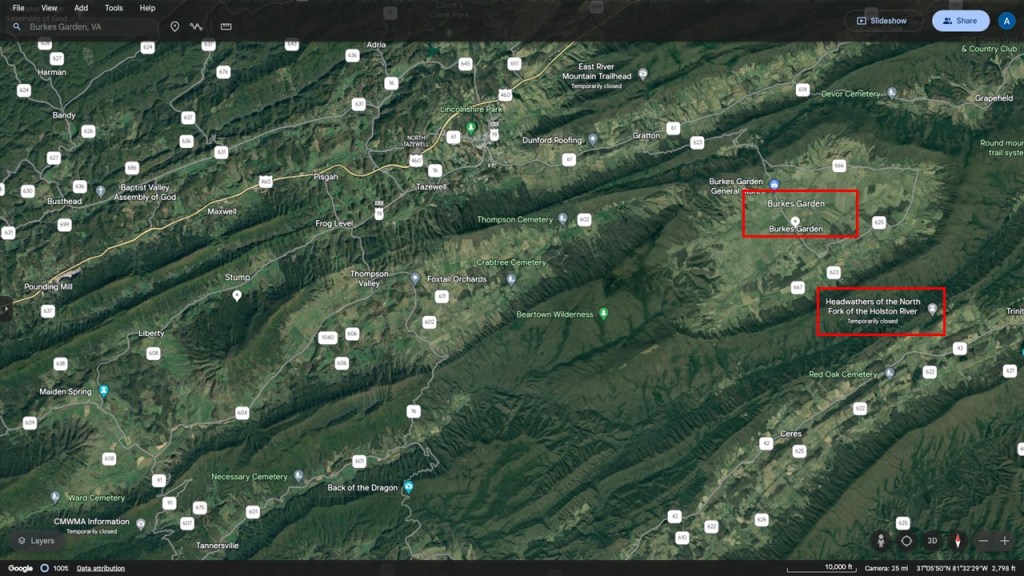

So Cranberry Glades is located near U. S. Route 219; it is very close to the Greenbrier River Trail, that ends in Cass and near Cheat Mountain; and is also very close to West Virginia’s Beartown State Park.

We already saw Beartown Rocks earlier in Clear Creek State Forest near Sigel, Pennsylvania, which is also close to the place where the 18-foot, or 5.5-meter,-tall skeleton was found in West Hickory, and where there is another rail-trail found at the Kennerdell Tract of the Clear Creek State Forest, both as previously mentioned at the beginning of this post.

Beartown State Park in West Virginia is located 7-miles, or 11-kilometers, southwest of Hillsboro, on the Eastern Summit of Droop Mountain, and right in the middle between Cranberry Glades and White Sulphur Springs.

There’s a couple of things to unpack here – one is Beartown State Park, and the other is the Civil War Battle of Droop Mountain.

First the rock formations at Beartown State Park in West Virginia are described as having “unusual rocky formations, massive boulders, overhanging cliffs, and deep crevices,” with the deep crevices having a regular criss-crossed pattern making them appear like the streets of a town.

This is very similar to how the Beartown Rocks back in Pennsylvania, were described, which was as ” a beautiful rock formation consisting of “house-sized” boulders, that are spread out far enough they have road-like spaces in-between them, making it feel like a “rock city.”

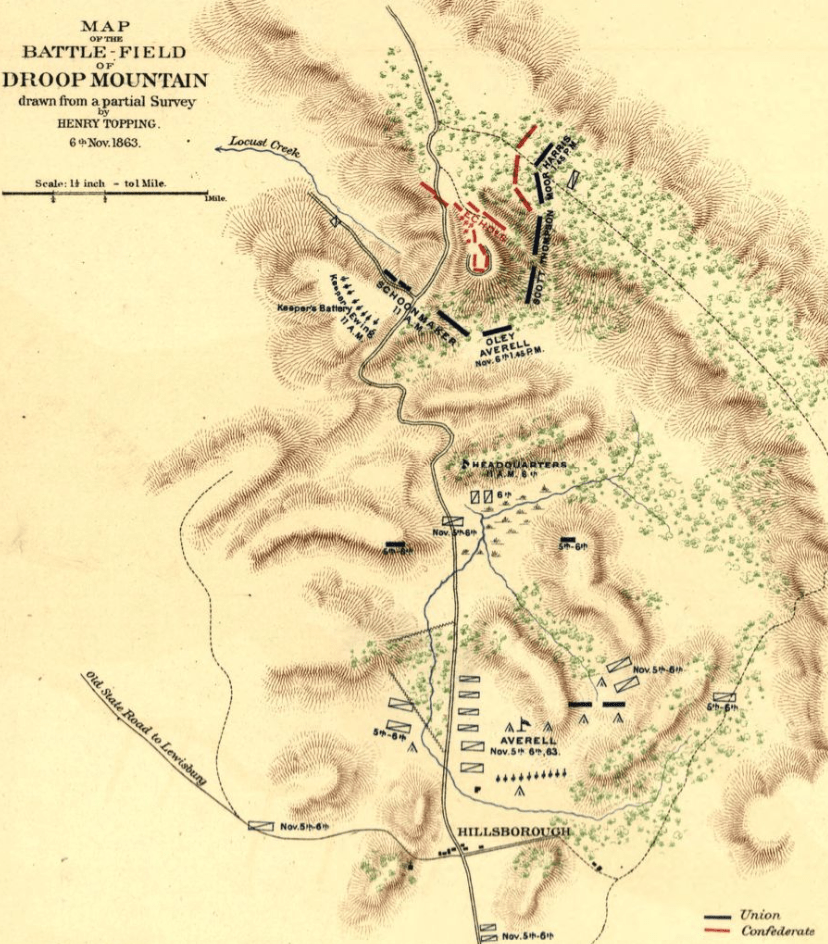

The Battle of Droop Mountain was said to be the largest battle, and last major battle, of the Civil War to take place in what was to become West Virginia.

It took place on November 6th of 1863.

This is what we are told.

Troops under Union Brigadier General William Averill defeated a smaller Confederate force under Brigadier General John Echols and Colonel William “Mudwall” Jackson.

While the Union succeeded driving Confederate forces from their locations on Droop Mountain, they were able to escape through Lewisburg before the arrival of Union reinforcements.

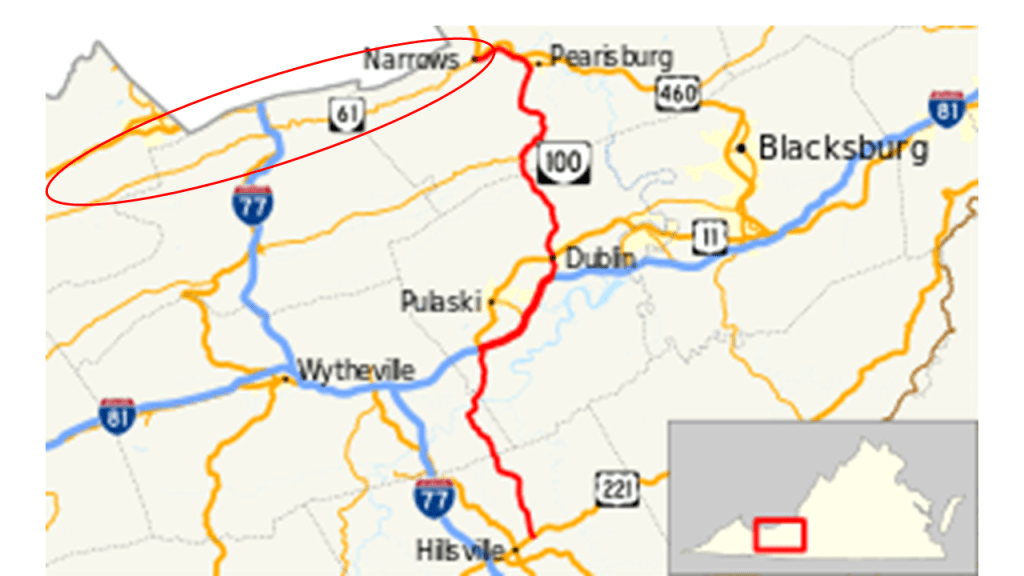

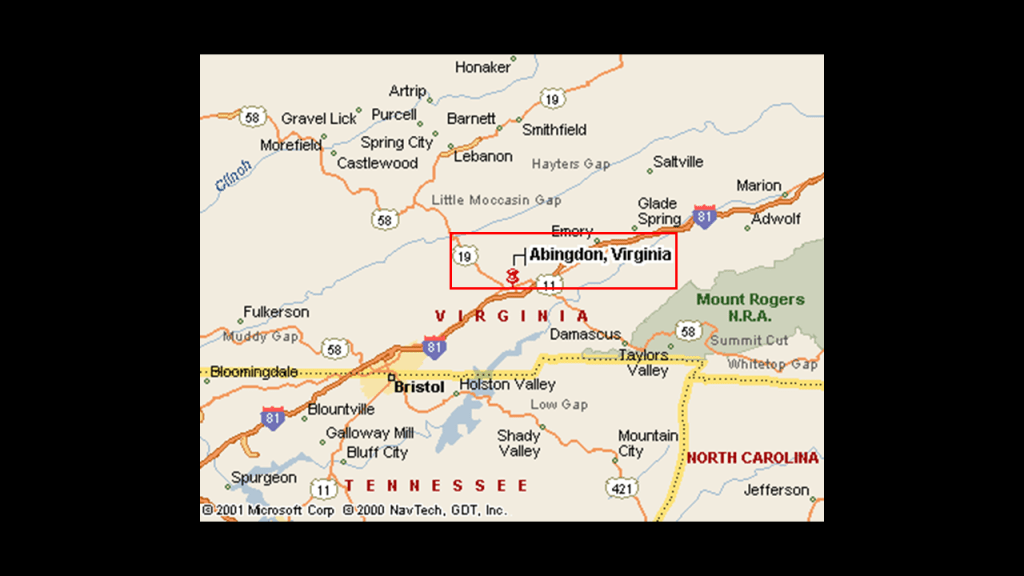

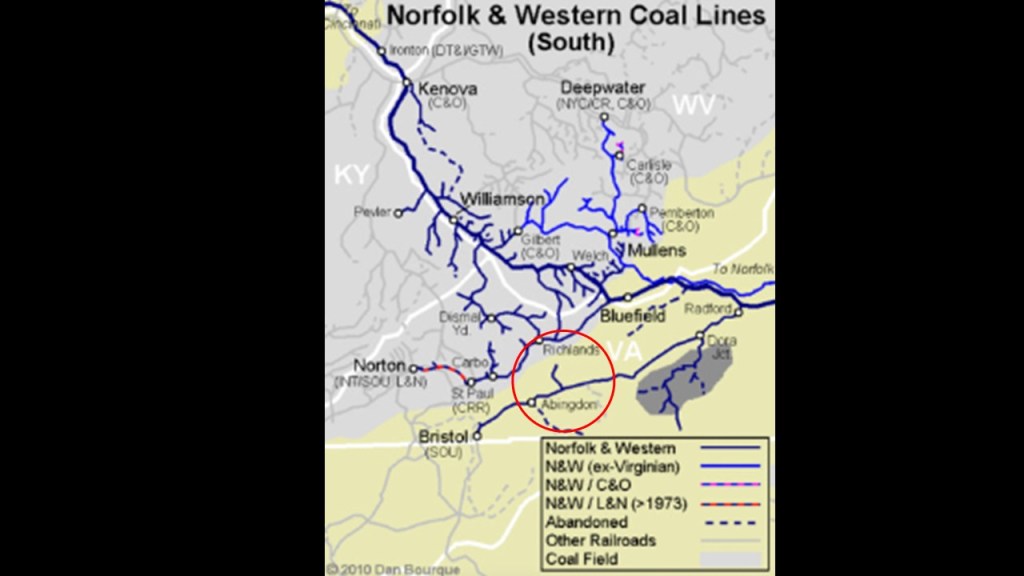

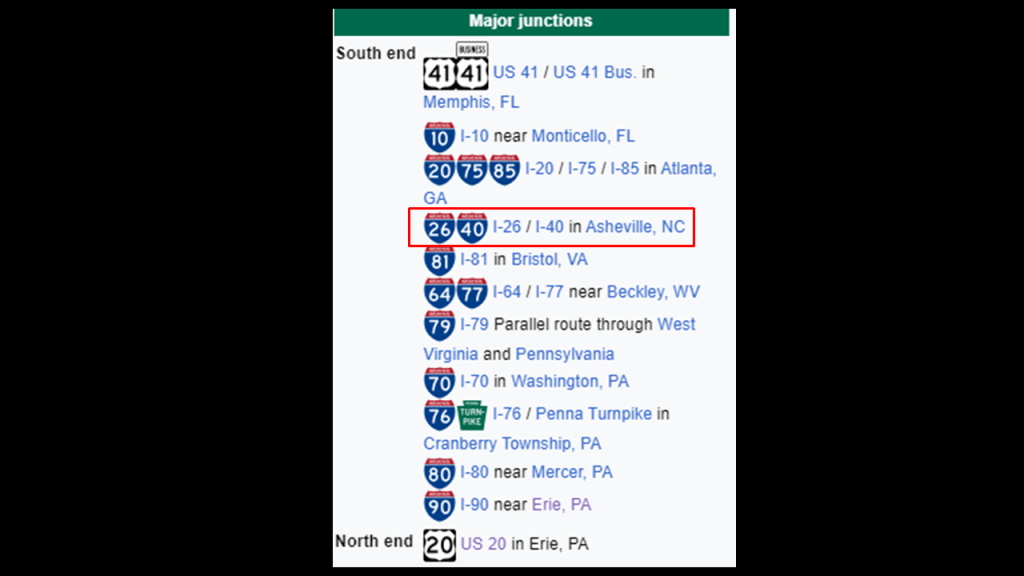

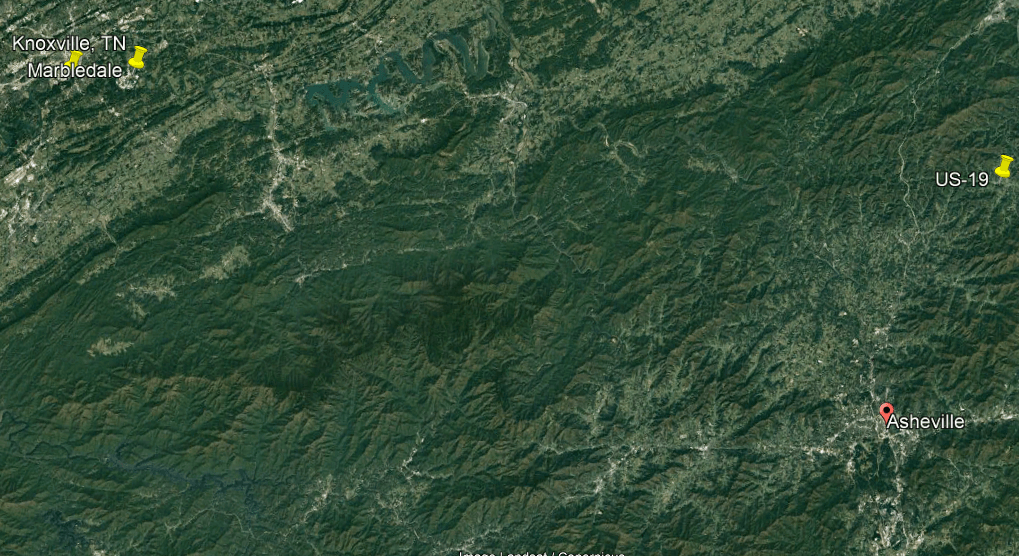

Though Lewisburg was captured, the Confederate forces returned later, and the Union did not succeed in it objective of damaging the Virginia and Tennessee Railroad that played a strategic role in supplying the Confederate Army.

So it was actually considered a tactical victory for the two Confederate Commanders, since the Confederate Army was not eliminated in Lewisburg, and the railroad was not disturbed.

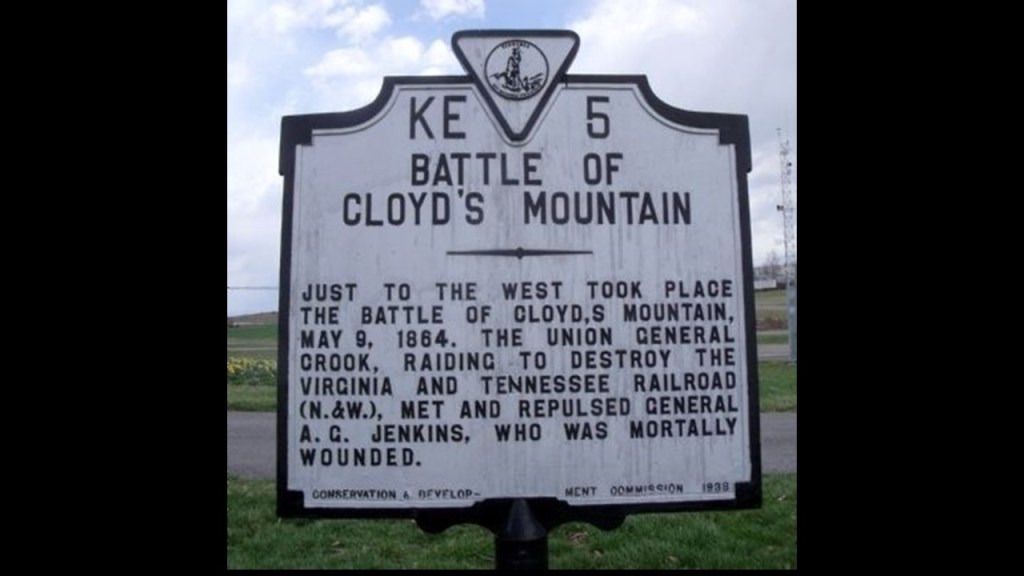

Interesting to note that the following year, on May 9th of 1864, Union troops under Brigadier General George Crook, successfully destroyed a large bridge across the New River on the Virginia and Tennessee Railroad during the Battle of Cloyd’s Mountain in southwestern Virginia, several more bridges along the railroad line and the depot at Dublin, Virginia.

This “victory” was said to sever one of the Confederacy’s last vital lifelines and only rail connection to Tennessee.

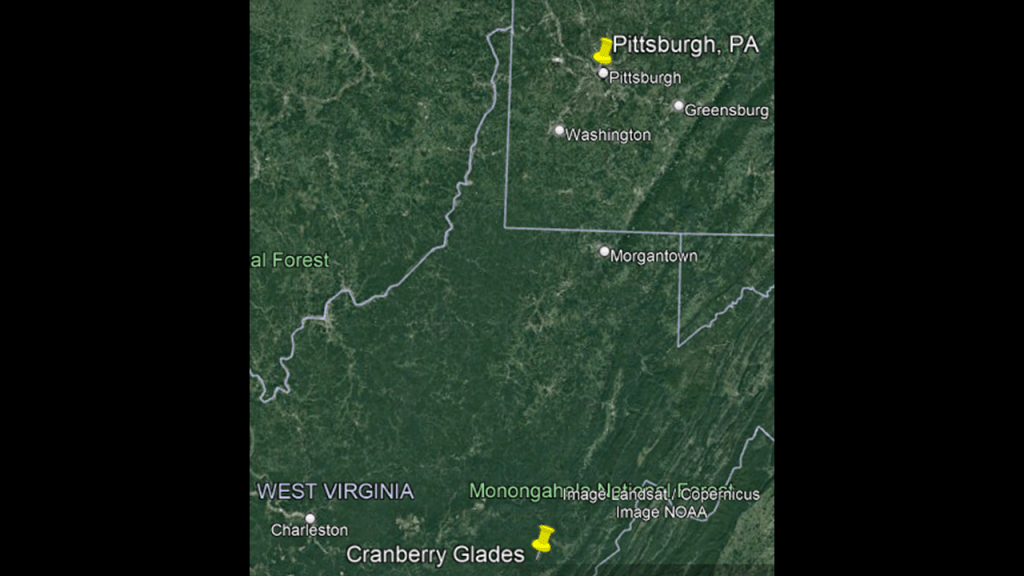

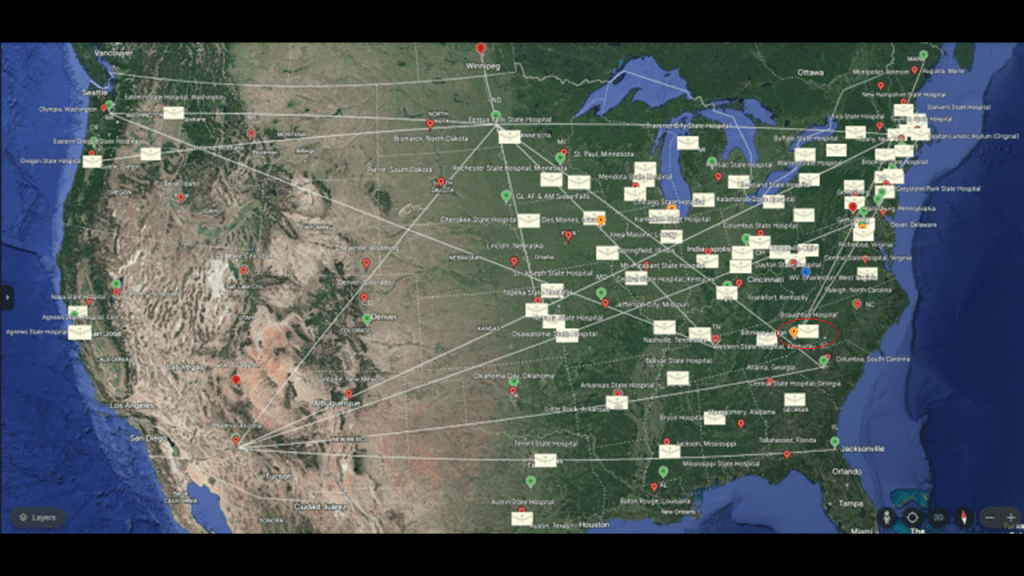

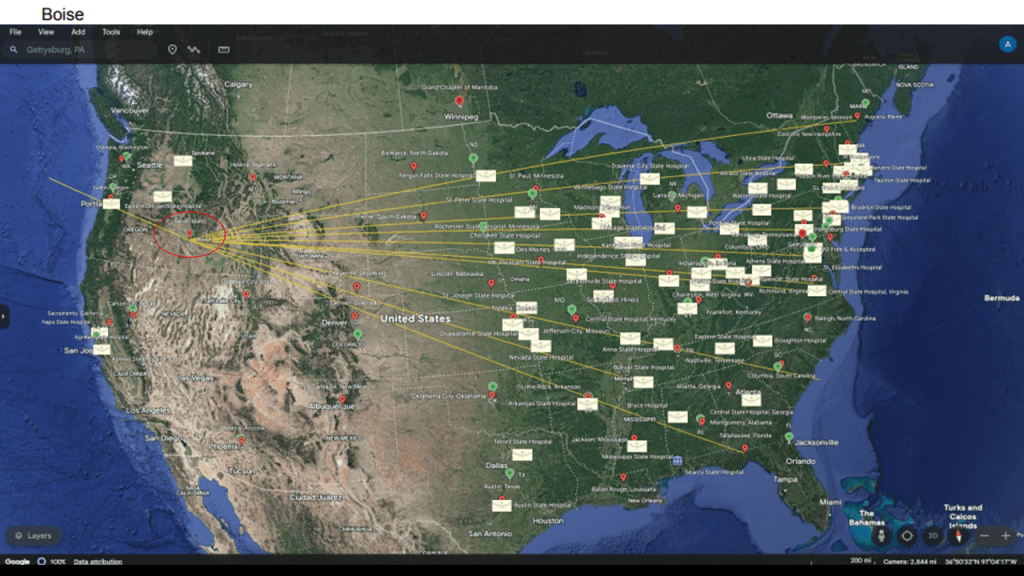

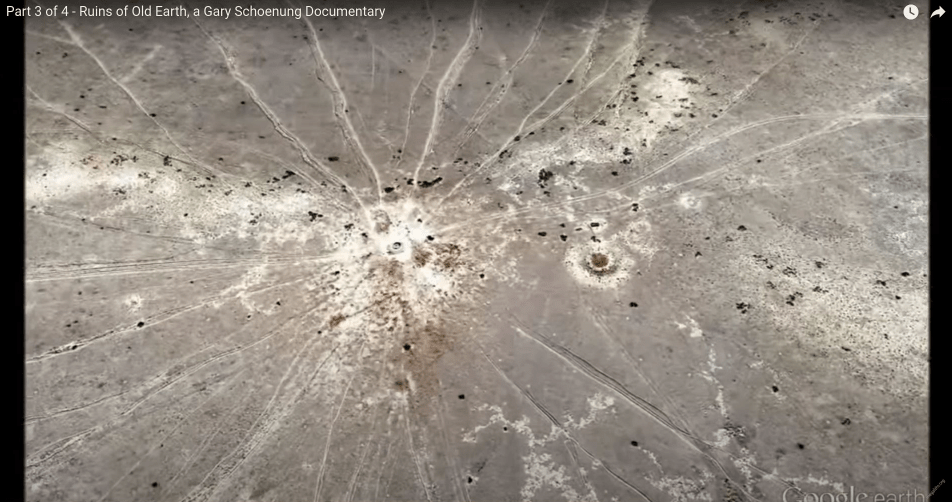

The last thing I would like to mention in the vicinity of the bogs of Cranberry Glades, there is a pattern of North-South-oriented, perfectly-straight parallel lines that are detectable in the landscape on Google Earth that Aaron had noticed and sent me this screenshot.

I followed the straight lines visible at Cranberry Glades northwards.

While not directly north of it, Pittsburgh isn’t far away from being due north of Cranberry Glades.

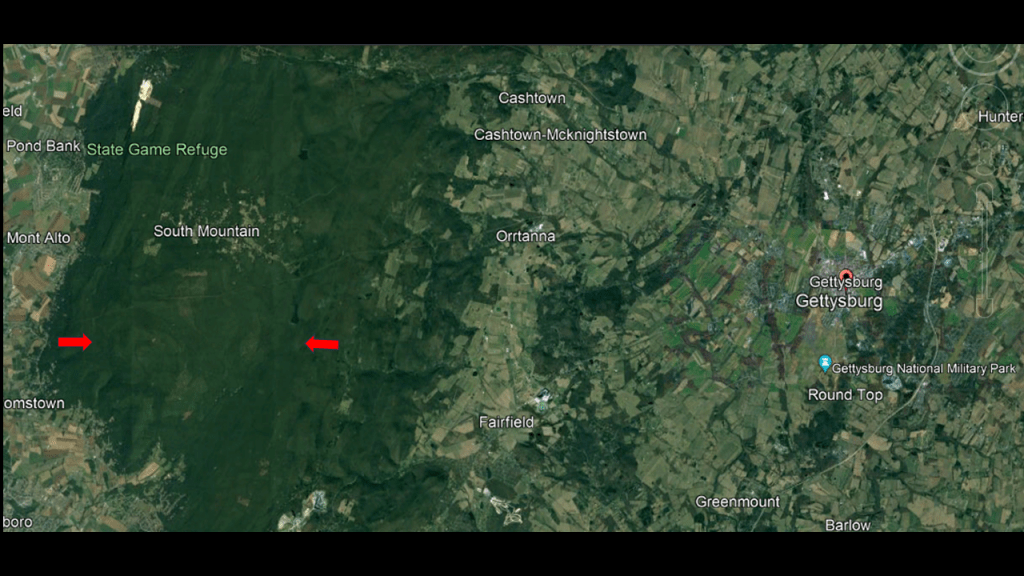

In addition, here’s a screenshot of the same kind of parallel lines appearing in the landscape west of Gettysburg that Aaron found, the historical location of a very famous Civil War Battle.

Could these massive parallel lines that are part of the landscape have been part of the Earth’s original energy grid system?

Now, I’m going to return to the area around the bog of Black Moshannon State Park and take another look there for the purposes of comparison to the area around Cranberry Glades.

Black Moshannon State park is 22-miles, or 35-kilometers, from State College, Pennsylvania, which is only a difference of 2-miles, or 4-kilometers, of the distance between the bogs at Cranberry Glades and the community of White Sulphur Springs, with its luxurious and exclusive Greenbrier Resort.

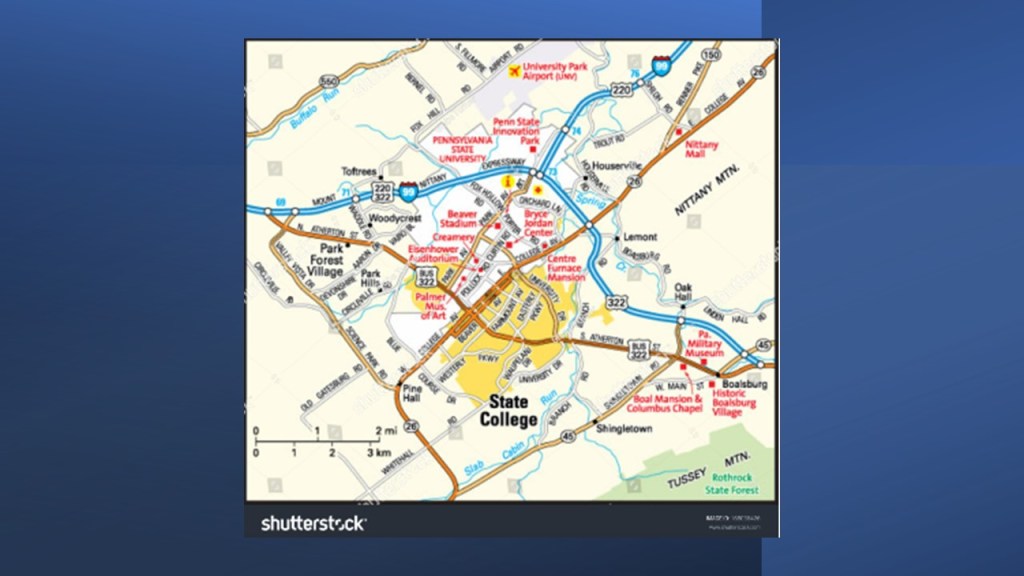

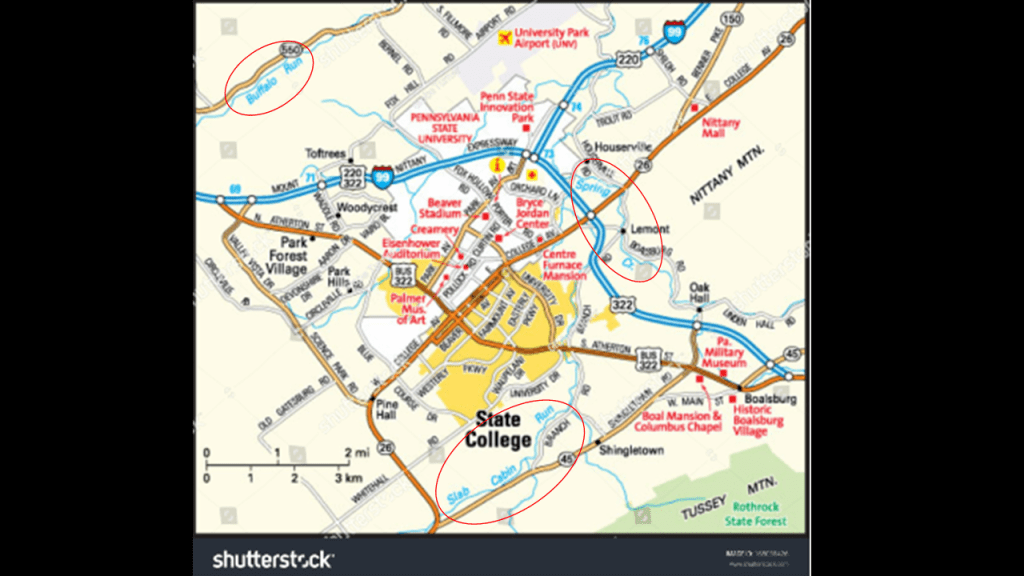

State College, Pennsylvania, is the home of Penn State University.

It is connected to Phillipsburg and Black Moshannon State Park via Pennsylvania U. S. Route 322.

Penn State was founded in 1855 as the Farmers’ High School of Pennsylvania, and in 1863, it became the state’s first land-grant university.

Besides U. S. Route 322, State College is surrounded by U. S. Route 220 (also part of I-99), and State Routes, like 550; 150; 45; and 26.

State College is also surrounded by s-shaped water courses, like Spring Creek, Buffalo Run, and Slab Cabin Run.

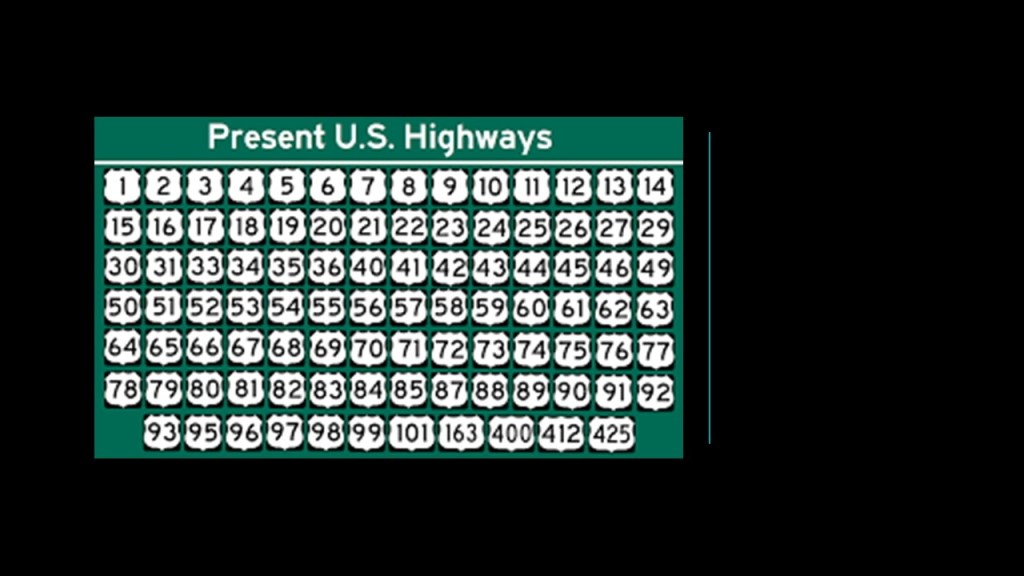

First a word about the United States Numbered Highway System, also known as the Federal Highway System.

It was actually called an “integrated network of roads and highways numbered within a nationwide grid across the contiguous United States.”

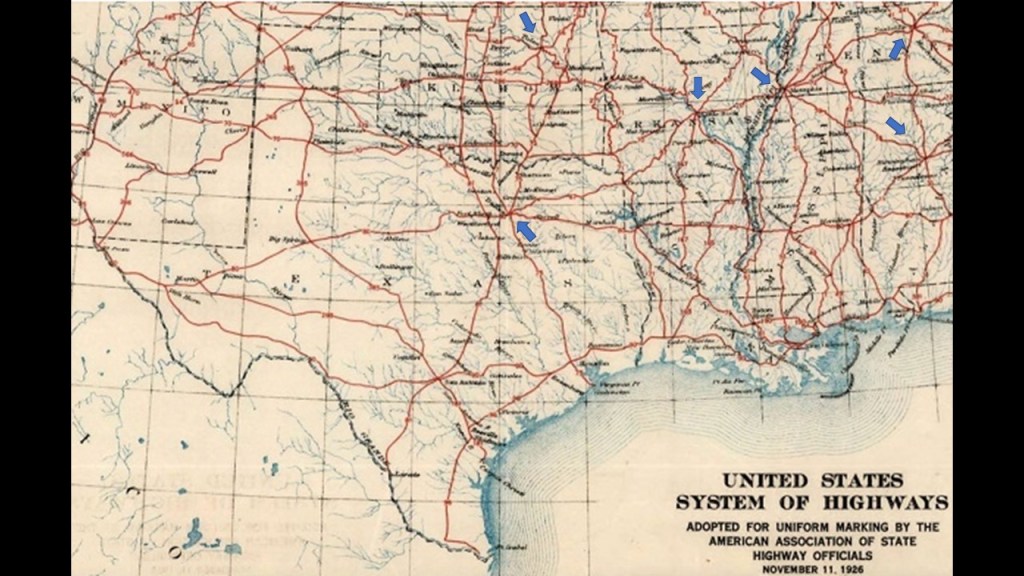

It was first approved in 1926.

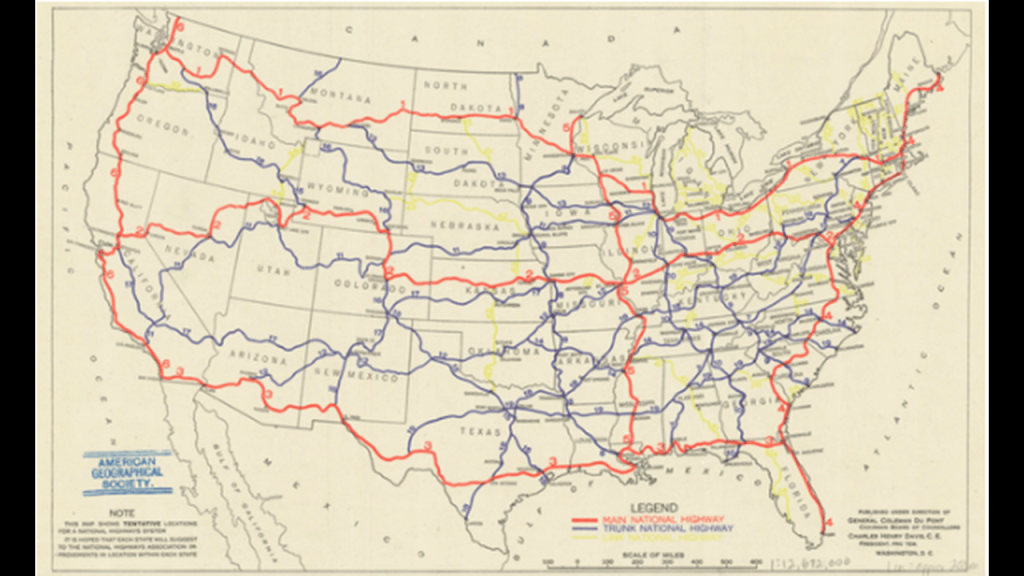

Drawn up in 1913, by the National Highway Association, thhe map was said to be the first proposed U. S. Highway Network map.

The red roads were delineated “Main” National Highways; the blue roads “Trunk” National Highways; and the yellow roads were “Link” National Highways to connect all the “Mains” and “Trunks.”

The Nation’s first Federal Highways would not be adopted until 1926, when the American Association of State Highway officials approved the first plans for the numbered highway system, with this section showing Texas, Oklahoma, Tennessee, Arkansas, Louisiana and Mississippi.

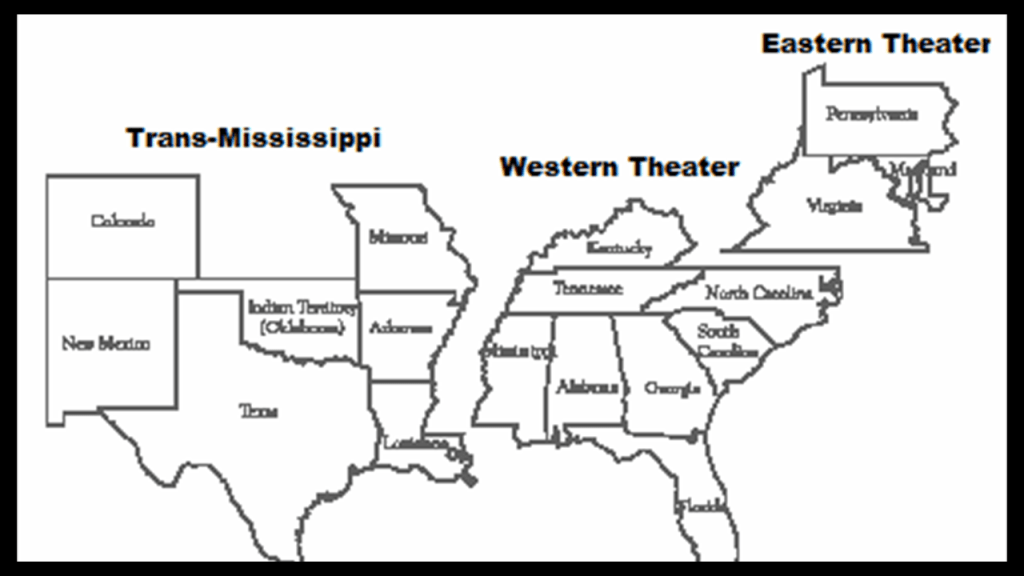

I have blue arrows pointinh to major cities that are the central point of at least five highways – Dallas, Texas; Tulsa, Oklahoma; Little Rock, Arkansas; Memphis, Tennessee; Nashville, Tennessee; and Birmingham, Alabama.

What we see happening with the highway system of certain cities being the central point of multiple highways, is also seen with rail-lines.

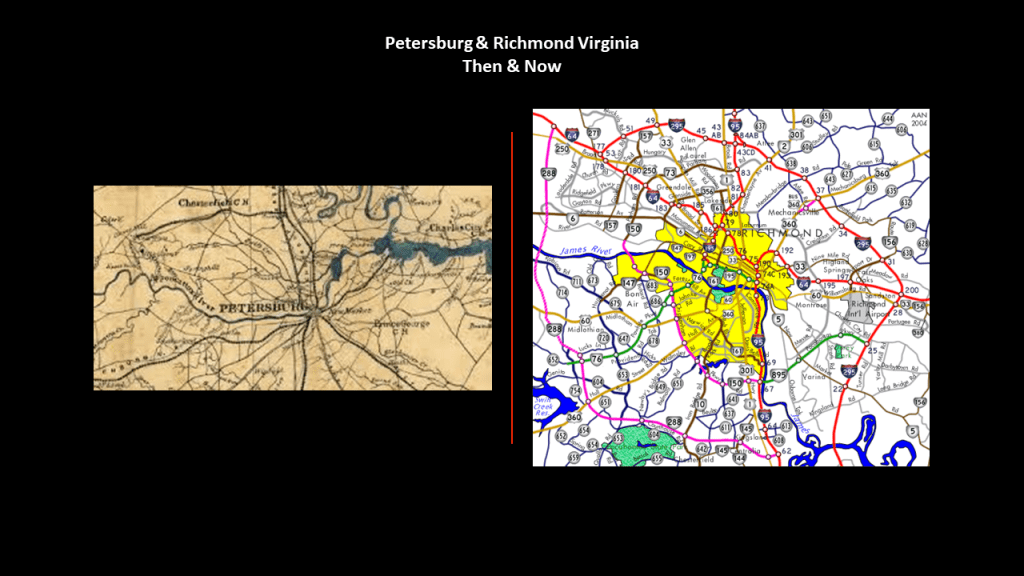

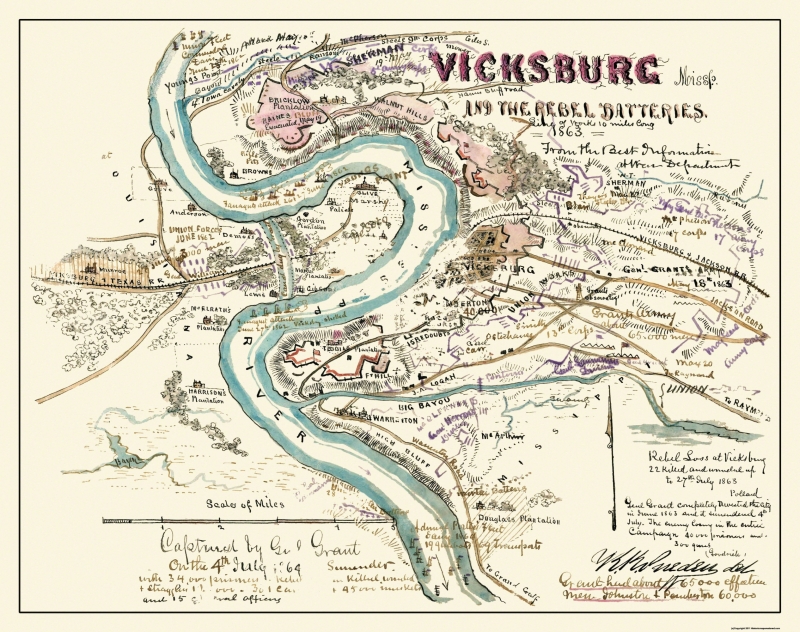

This Civil War era-example shows that Petersburg in Virginia, just south of Richmond, was a central point of multiple rail-lines emanating from it in all directions.

Petersburg was the focal point of the railroads that supplied Richmond during the Civil War, and was the primary target for the Union Army in Virginia from the last half of 1864 until April of 1865.

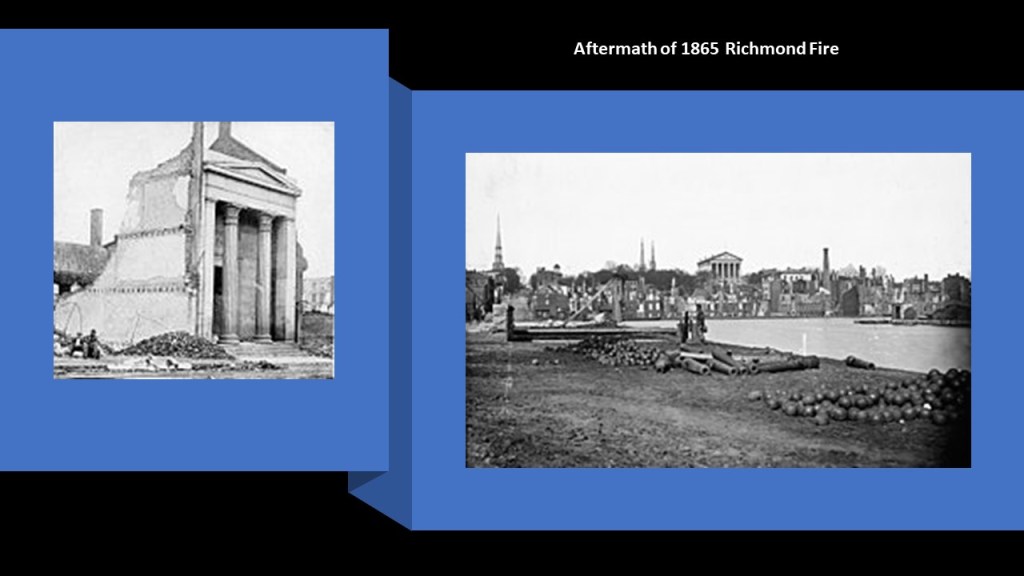

The third major Civil War fire was the April 2nd of 1865 Burning of Richmond, the capital of Virginia, and of the Confederate States of America.

Also known as the “Evacuation Fire,” and the “Fall of Richmond,” Richmond was set on fire on the night of April 2nd by Confederate forces after Confederate President Jefferson Davis was said to have ordered the burning of warehouses and bridges after Union General Ulysses S. Grant had taken nearby Petersburg.

This is a lithograph depicting it by Currier & Ives.

The huge classical temple-like building on the left was the Exchange Bank of Richmond, and said to have been damaged by the fire, and on the right is another view of Richmond and its State Capitol Building in the middle of the picture, as seen from above the Canal Basin in Richmond after the 1865 fire.

In our historical narrative, the Confederate General Robert E. Lee surrendered to General Grant days later, on April 9th of 1865, after his final defeat at the Battle of Appomattox Court House that same day.

There’s a very similar configuration between Petersburg Rail-lines of the Civil War-era, and the highways around Richmond and Petersburg today.

Two other major fires in history have come down to us as Acts of War during the American Civil War.

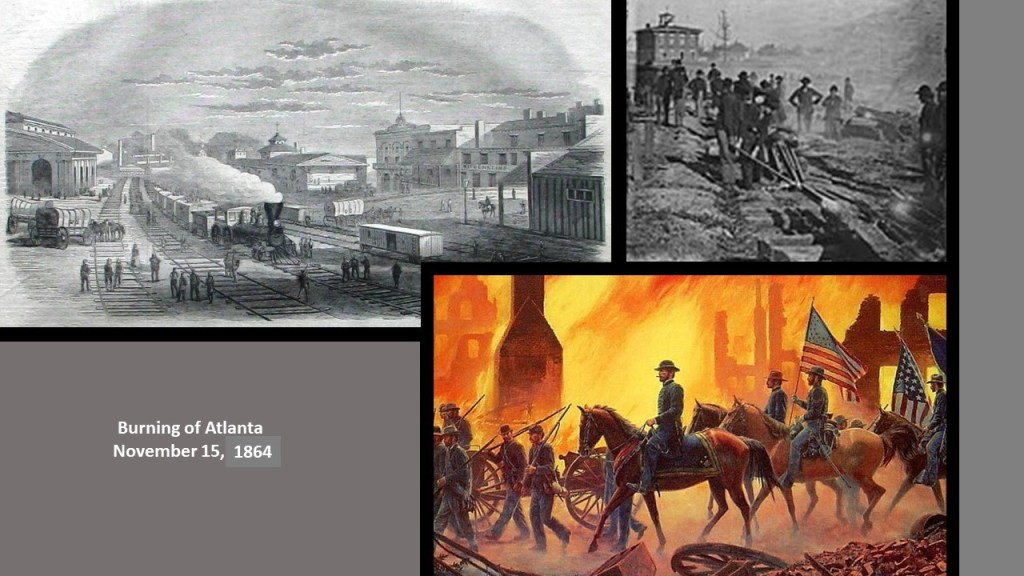

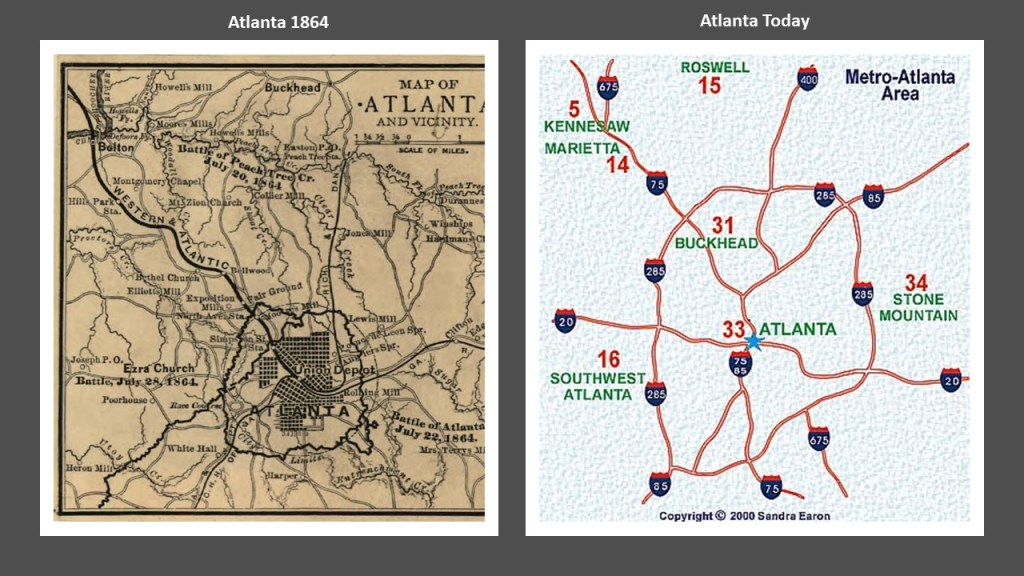

The first was the Burning of Atlanta, which we are told took place in 1864.

Atlanta was an important rail and commercial center at the time of the Civil War.

General Sherman and his Union Forces captured the city of Atlanta in September 2nd of 1864, and occupied from then until November of 1864.

He gave orders to destroy Atlanta as a transportation hub and as a war material manufacturing center, and in particular the railroad system and everything connected to it.

His orders were carried out destroying physical infrastructure, and on November 15th, everything that had been destroyed was set on-fire.

Like Petersburg/Richmond, Atlanta was a railway hub at the time of the Civil War, and is a highway hub today.

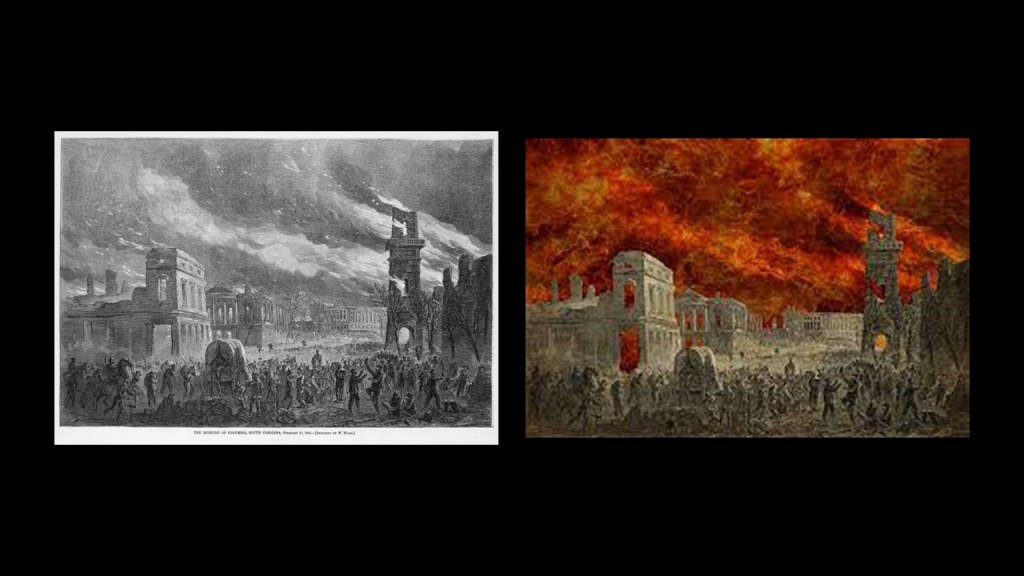

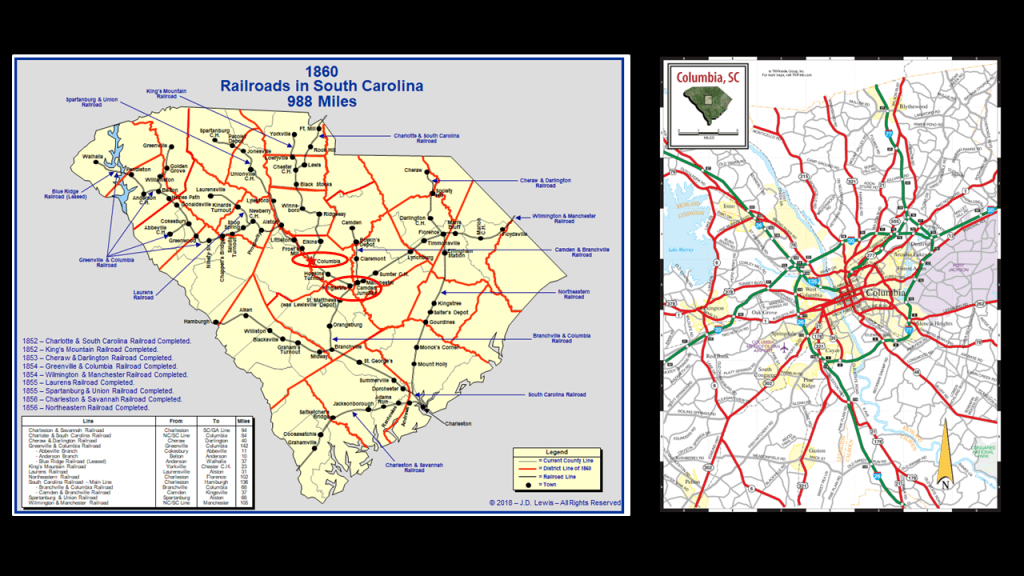

Then, Atlanta was burned down by General Sherman and his troops in November, the following February, Columbia, the capital of South Carolina and an important political and supply center for the Confederacy, was said to have surrendered to General Sherman on February 17th, 1865, after the Battle of Rivers’ Bridge.

On the same day, the fires started, burning much of Columbia, though there is disagreement between historian regarding whether or not the fires on that day were accidental or intentional, but on the following day, General Sherman’s forces destroyed anything of military value, including railroad depots, warehouses, arsenals, and machine shops.

Famous illustration of Columbia burning on the left, with a colorized version on the right that highlights more detail on the appearance of the burning buildings.

Like Petersburg/Richmond and Atlanta, Columbia was a transportation hub with regards to rail infrastructure, and a highway hub today.

Back to State College in Pennsylvania.

As I mentioned previously, besides State and US Routes, State College is also surrounded by s-shaped water courses, like Spring Creek, Buffalo Run, and Slab Cabin Run.

And, yes, there is a railroad history to be found in the area around State College too.

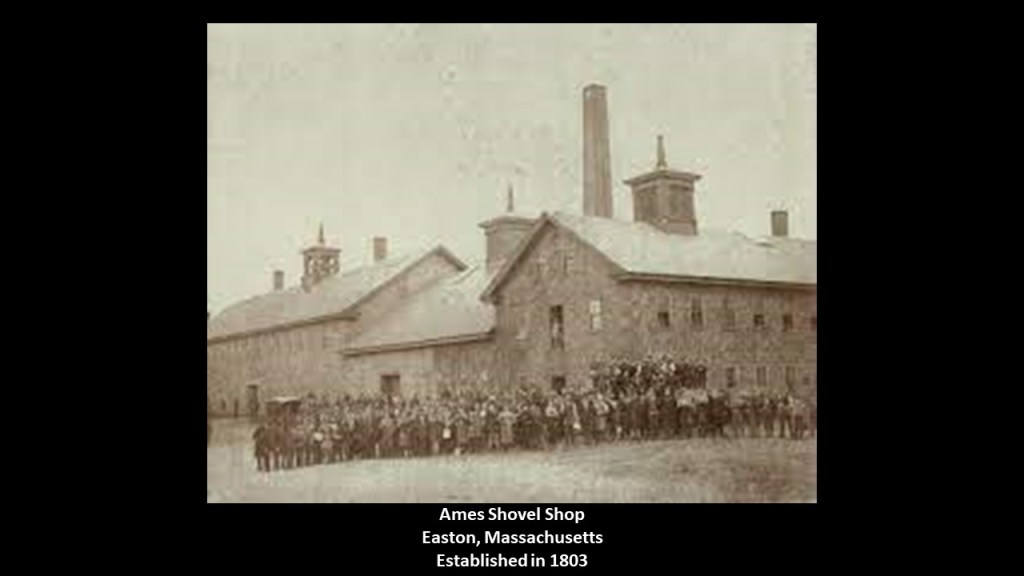

Whereas West Virginia was mined exhaustively for its coal, this part of Pennsylvania came to be mined exhaustively for its iron ore.

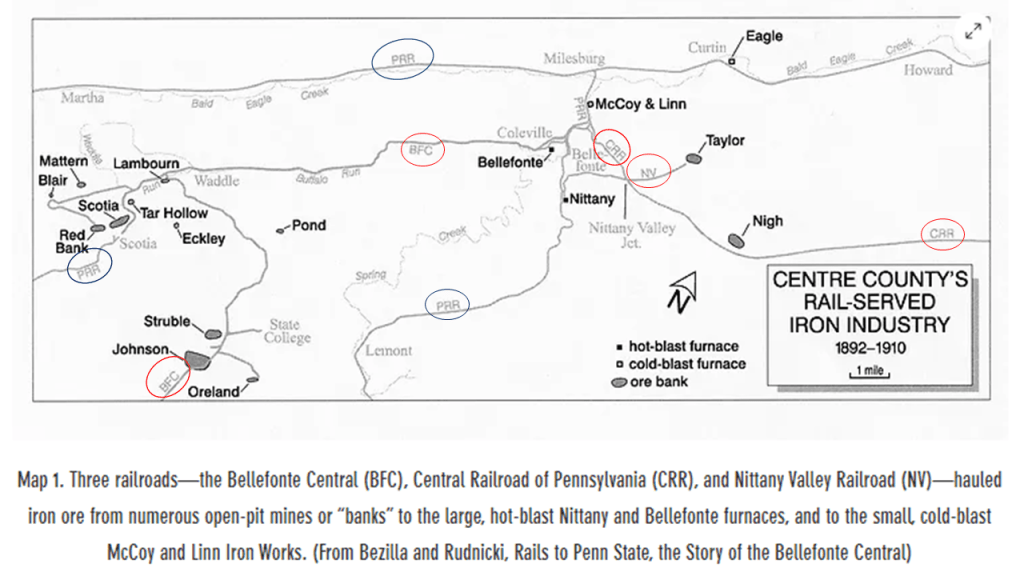

Andrew Carnegie had begun mining iron ore in Scotia in 1881 for his steel mills in Pittsburgh, and by 1887, we are told that a new era of iron-making in the Nittany Valley began, with the opening of the Nittany and Bellefonte Furnaces along Buffalo Run near its junction with Spring Creek, and three railroads that were said to have been constructed to haul the iron ore to them – the Bellefonte Central (BFC), Central Railroad (CRR) and Nittany Valley Railroad (NV).

By 1911 both of these furnaces had been shut-down.

By 1950, all the railroads that had once served the area, either for the iron-related industry or passenger service, including the Pennsylvania Railroad lines, circled in blue, were no longer in service.

The only rail here that became operational again was a portion of the Bellefonte Central after the Bellefonte Historical Railroad was organized as an excursion line in 1985, and occasionally offers runs as a tourist attraction.

A couple of other things that I found looking around State College.

First, I looked to see if Penn State University has an underground tunnel system, and it does, though its origin seems mysterious for some reason.

We are told there is a system of tunnels said to have been built for maintenance purposes, and many of which are used today to generate steam to heat the Penn State sidewalks and keep them clear of snow in the wintertime, and other tunnels for other maintenance purposes.

Interesting to note that the Garfield Thomas Water Tunnel, the world’s largest water tunnel at the time it was built in cooperation with the Navy in 1949, is at Penn State, and for a long time was the largest circulating water tunnel in the world.

It is still one of the Navy’s principal experimental hydrodynamic research faciilities, and has been declared a historic mechanical engineering landmark.

Also, Penn State University lies at the foot of Mount Nittany.

Mount Nittany was said to have gotten its name from the Algonquin word “Nit-a-Nee,” meaning “Single Mountain.”

For the purposes of comparison for similarity, I recently found a different university with tunnels on a route near a single mountain.

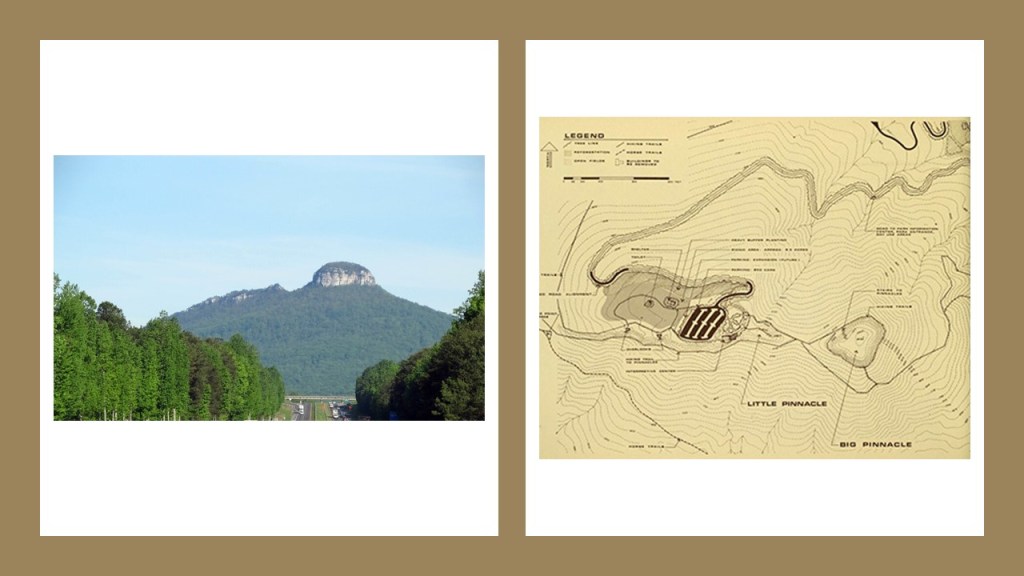

In this photo of the Wake Forest University Campus, you can see the Wait Chapel building in a direct alignment with Pilot Mountain in the background.

The tunnels at Wake Forest University were also said to have been built for heating and maintenance purposes. They have tours, but they are typically not open for public view.

Pilot Mountain, which was just pictured in alignment with the Wait Chapel on the Wake Forest, is described as one of the most distinctive natural features in the State of North Carolina, with two distinctive features, one named “Big Pinnacle,” and the other “Little Pinnacle.”

It is seen here centered on U. S.. Route 52.

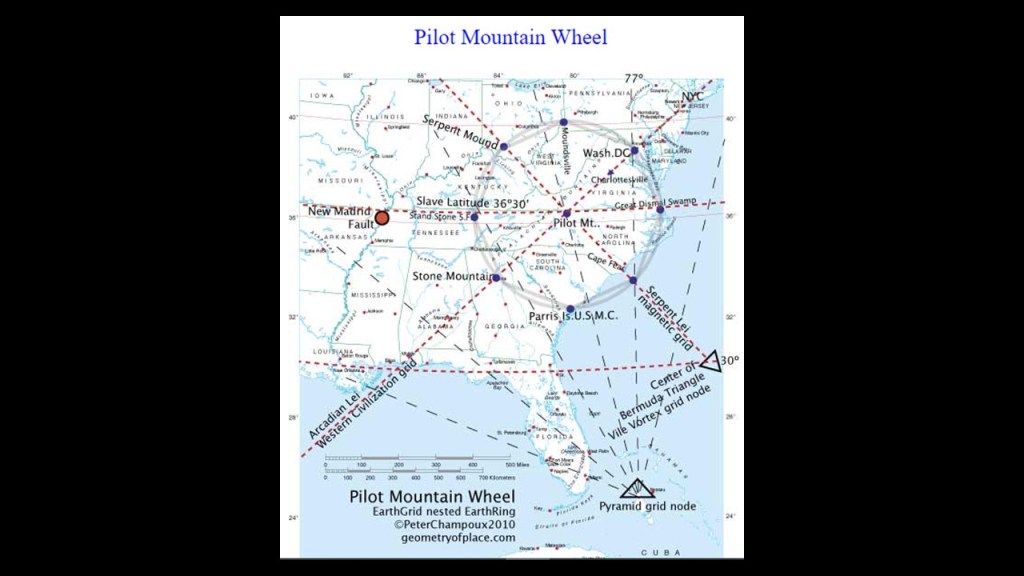

Peter Champoux has done incredible work on specific ley-lines in North America, and other continents as well, as seen on his website geometryofplace.com

He shows Pilot Mountain as a hub for ley-lines on the home page of his website, looking much like the cities we just saw that serve as transportation hubs for multiple rail-lines and/or highways.

Not long ago, I researched places along the ley-line Peter identified as the “Serpent Lei.”

I started at the Bermuda Triangle, and ended at Lake Itasca in Minnesota, the headwaters of the Mississippi River.

In the process of doing the research of places along this ley-line, I learned about a lot of the things I have mentioned in this post, including this alignment between Wake Forest University and Pilot Mountain, among other things.

Pilot Mountain is described as a “Quartzite Monadnock.”

This translates to a “hard, metamorphic rock that was originally pure quartz sandstone that is an isolated rock hill, knob, ridge, or small mountain that rises abruptly from a gently sloping or virtually level surrounding plain.”

Here are some other examples of places classified as “Monadnocks.”

Besides Pilot Mountain on the top left, Harteigen in Norway is seen on the top right; Devil’s Tower in Wyoming on the bottom left; and Cooroora in Australia on the bottom right.

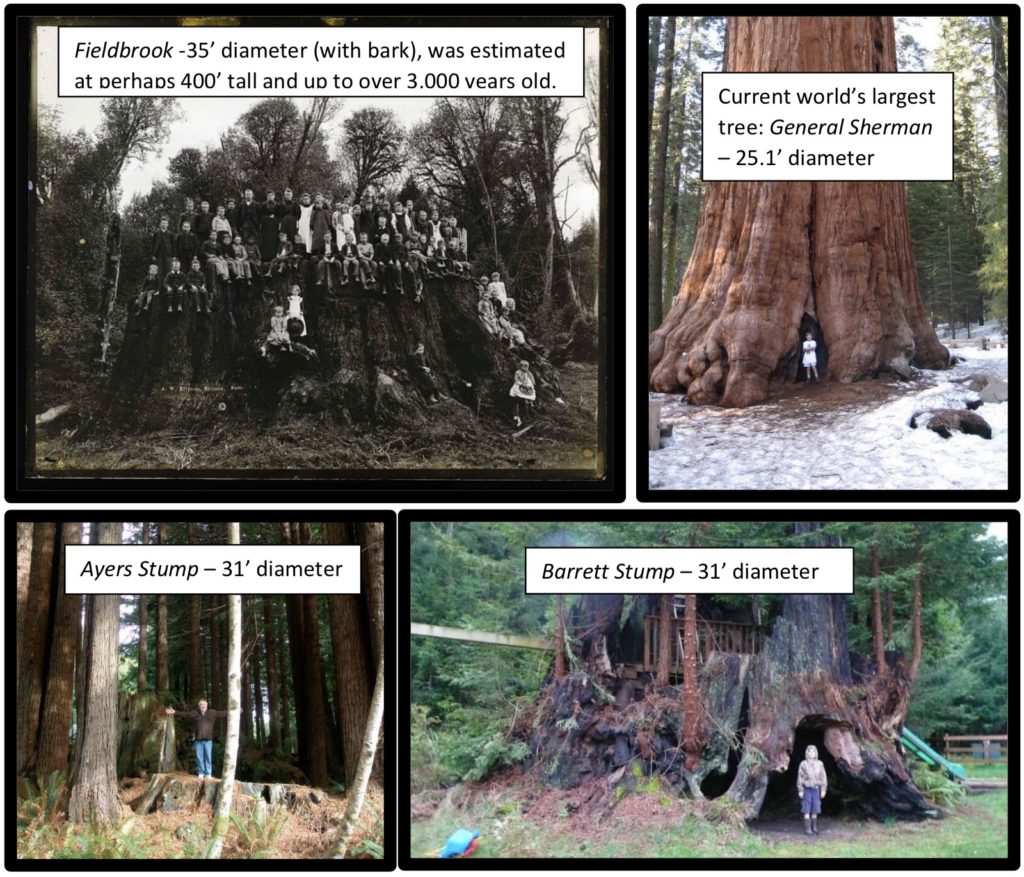

What if “Monadnock” is a word used to cover-up gigantic tree stumps?

Here are some examples of giant trees and stumps that are identified as such.

This is a view of Earth from space of the southern Appalachians on the left, in comparison with what an extensive tree root system looks like on the right.

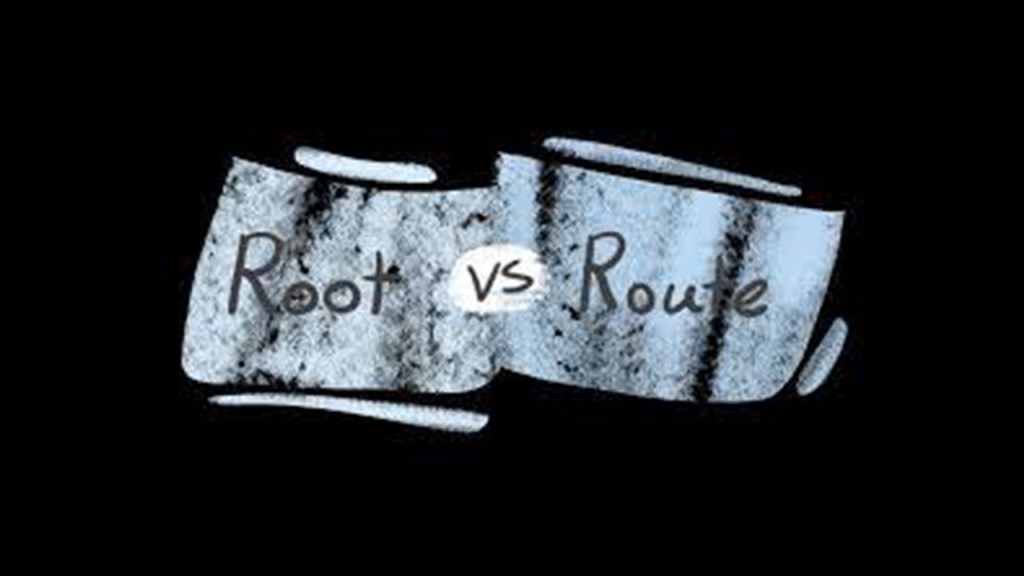

More to come later in this post on the possible connection between the English word “root,” meaning the underground parts of a tree that anchor it,” and “route,” meaning “a particular way or direction between places, including a road or highway.”

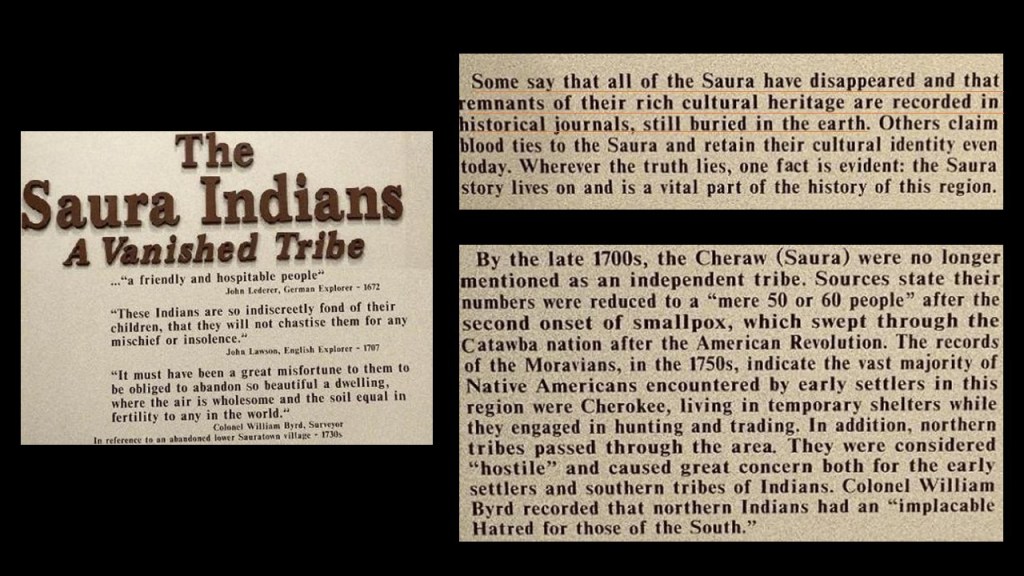

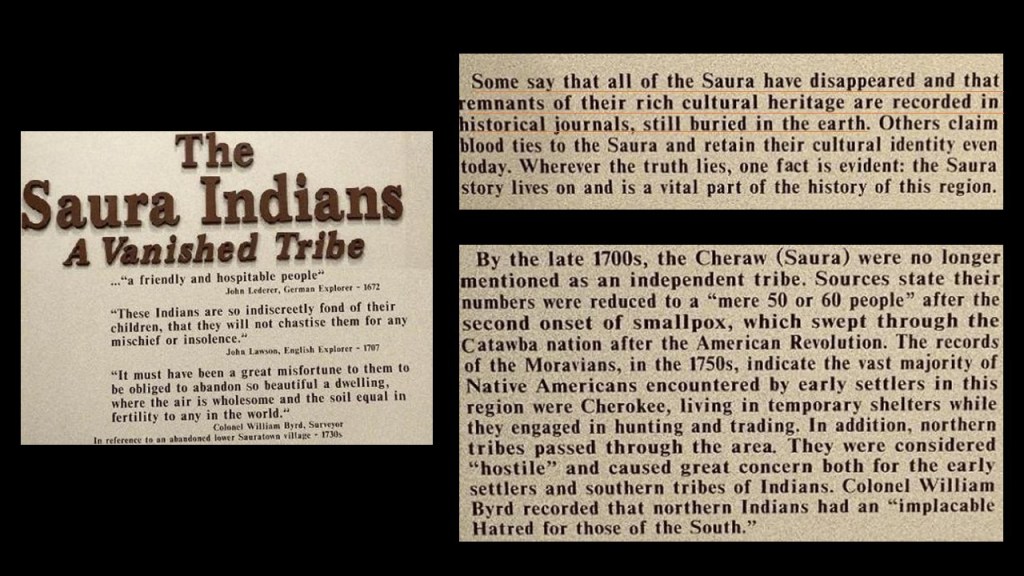

So, Pilot Mountain State Park is on the western end of what are called the “Sauratown Mountains,” named after the Saura, or Cheraw People, the Siouan-speaking indigenous people who lived here before the arrival of Europeans.

They are described as an isolated mountain range, sometimes called “the mountains away from the mountains.”

When I was looking up information about the Saura/Cheraw people, I found historical records mentioning a vanished tribe, and “remnants of their rich cultural heritage recorded in historical journals, still buried in the earth.”

I will come back to this finding later in this post.

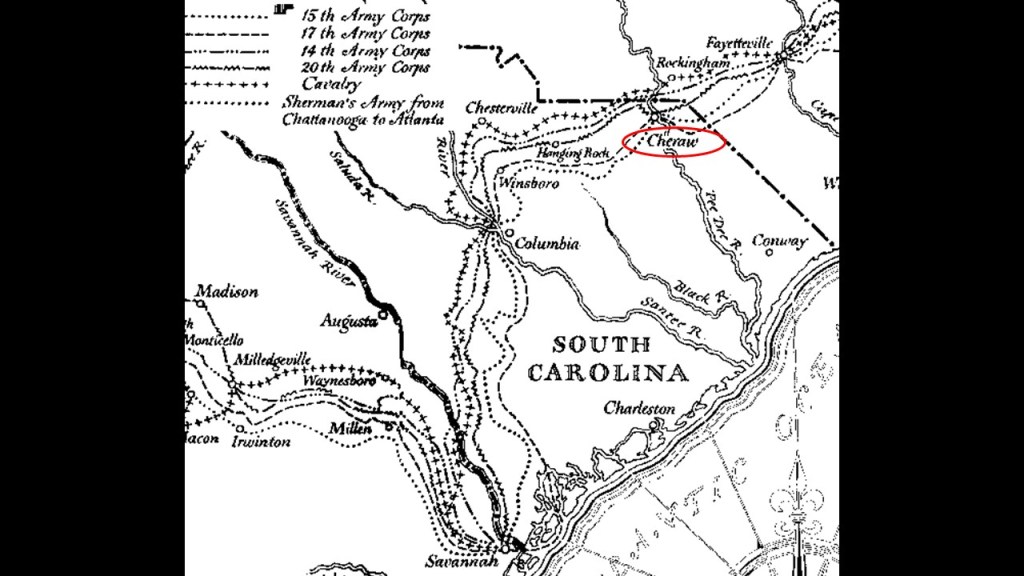

Interesting to note that I found this reference to a place called “Cheraw,” that still exists today, in this Civil War-related map of the movements of Sherman’s Army around Columbia, South Carolina, on the Pee Dee River that flows from the western North Carolina region of the Sauratown Mountains through today’s South Carolina on its way to the Atlantic Ocean.

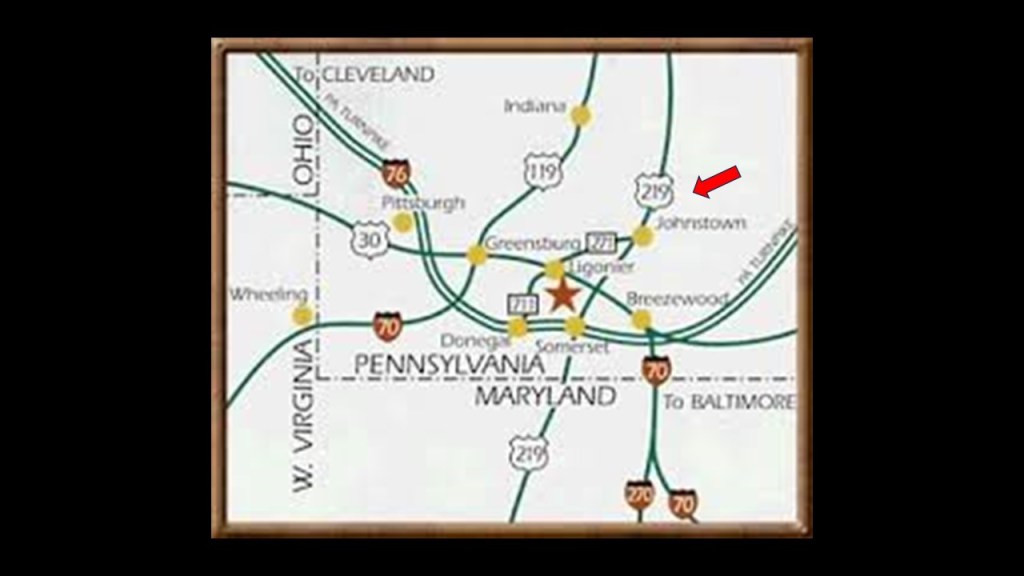

Now I am going to take a look at Altoona in Pennsylvania just down the road from State College.

Altoona is only 43-miles, or 70-kilometers southwest of State College.

Altoona was said to have been established by the Pennsylvania Railroad in 1849.

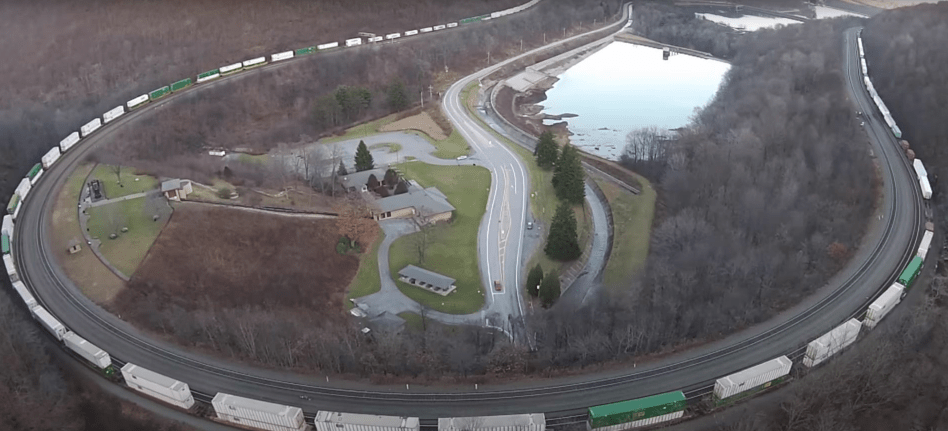

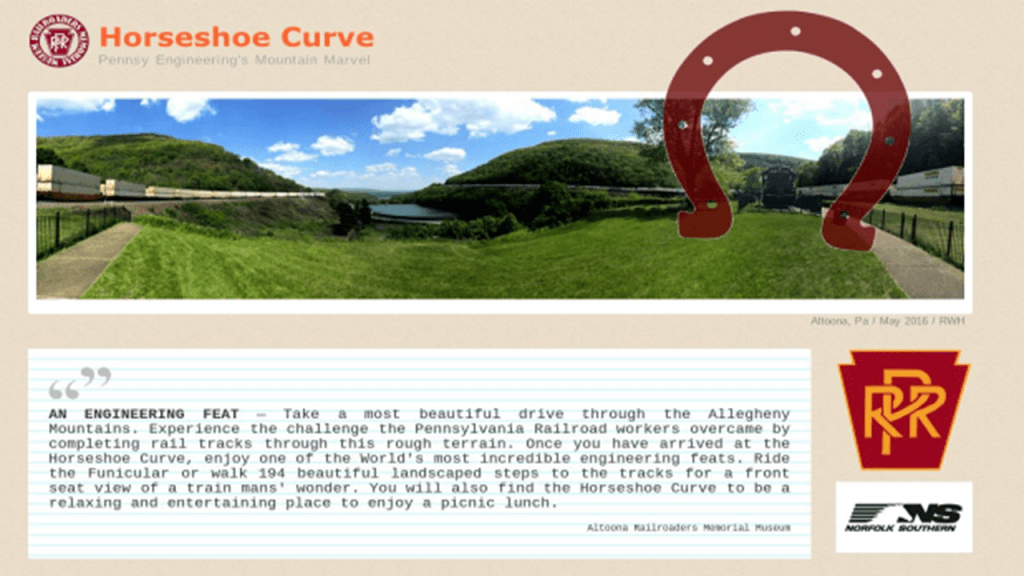

Aaron drew my attention to Altoona with information he sent me about the nearby “Horseshoe Curve.”

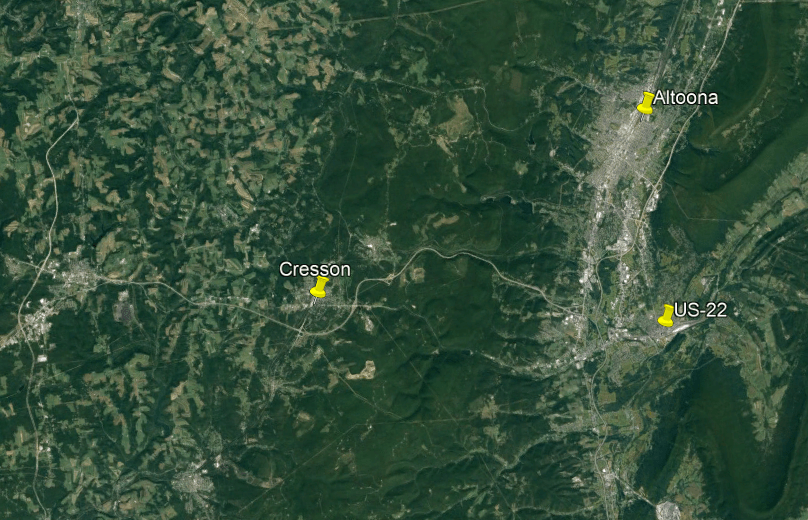

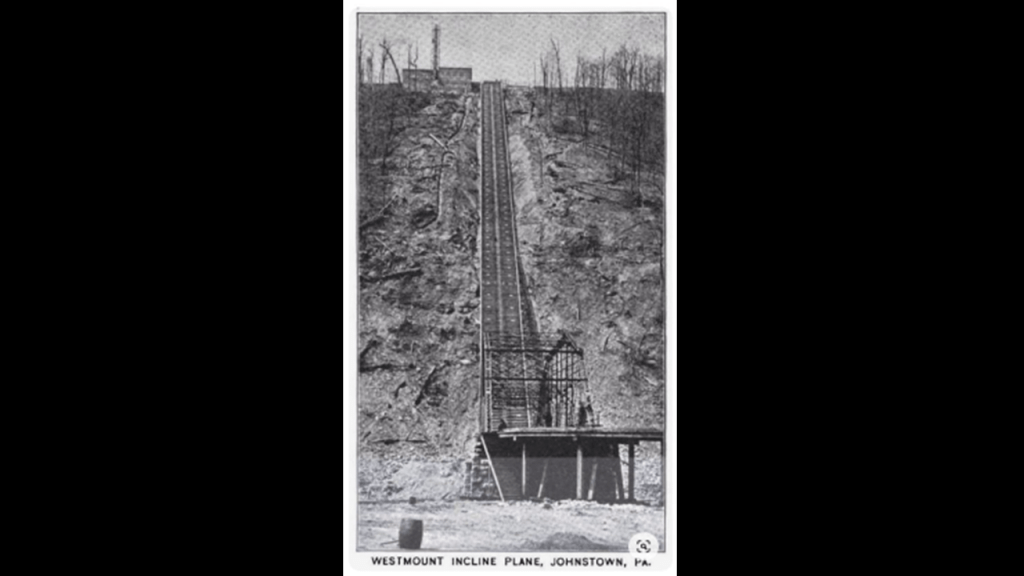

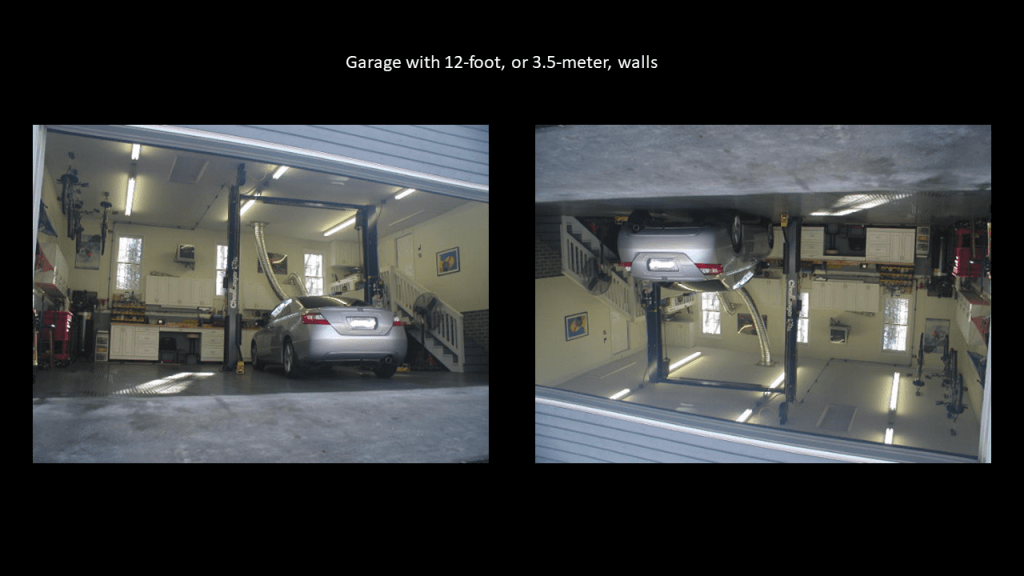

The “Horseshoe Curve” is a three-track railroad curve that is described as one of the world’s most incredible engineering feats, and was accomplished by the Pennsylvania Railroad in 1854 as a way to reduce the westbound grade to the summit of the Allegheny mountains.

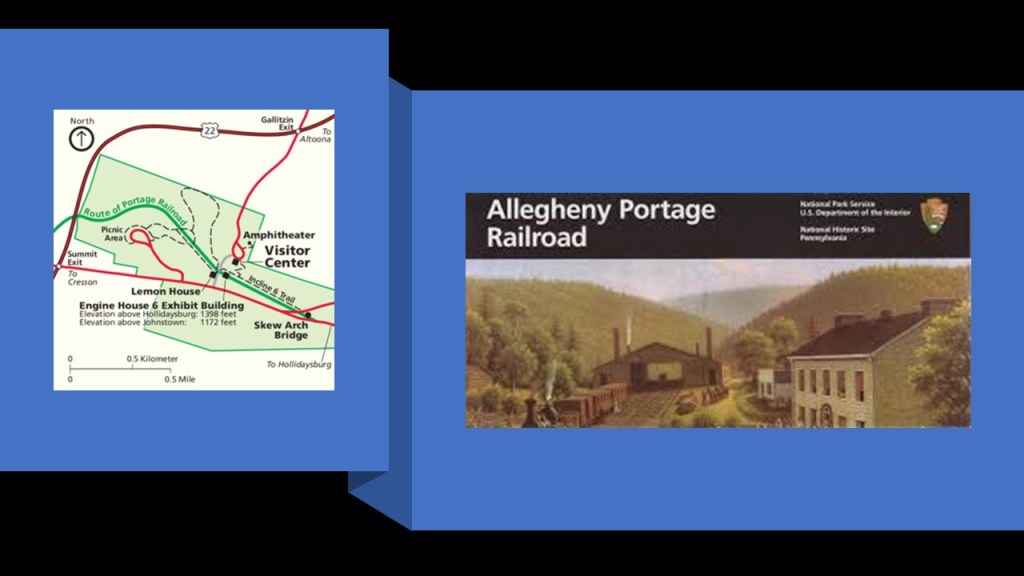

It was said to have replaced the original Allegheny Portage Railroad, which was said to be the first railroad constructed through the Allegheny Mountains in 1834, and which was 36-miles, or 58-kilometers,-long, and connected to the Pennsylvania Canal, all of which was said to have been built as part of the transportation by the “Main Line of Public Works” that was mentioned at the beginning of this post after it was passed by the Pennsylvania Legislature in 1826.

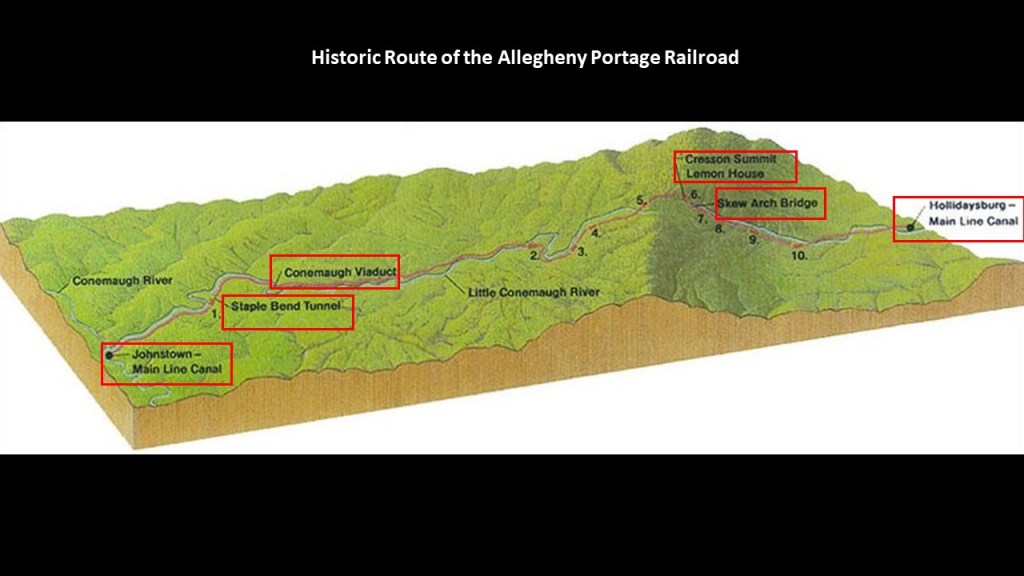

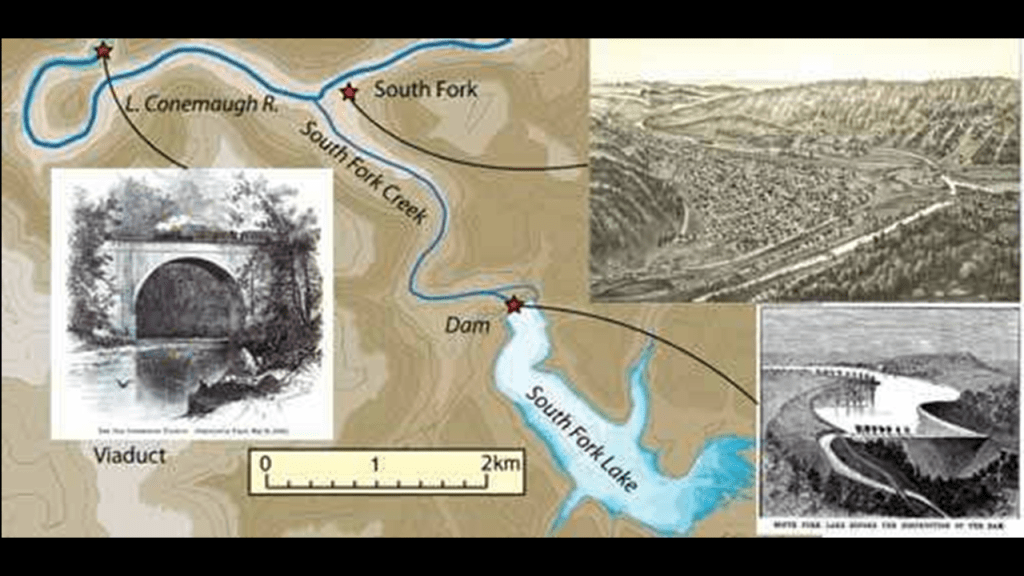

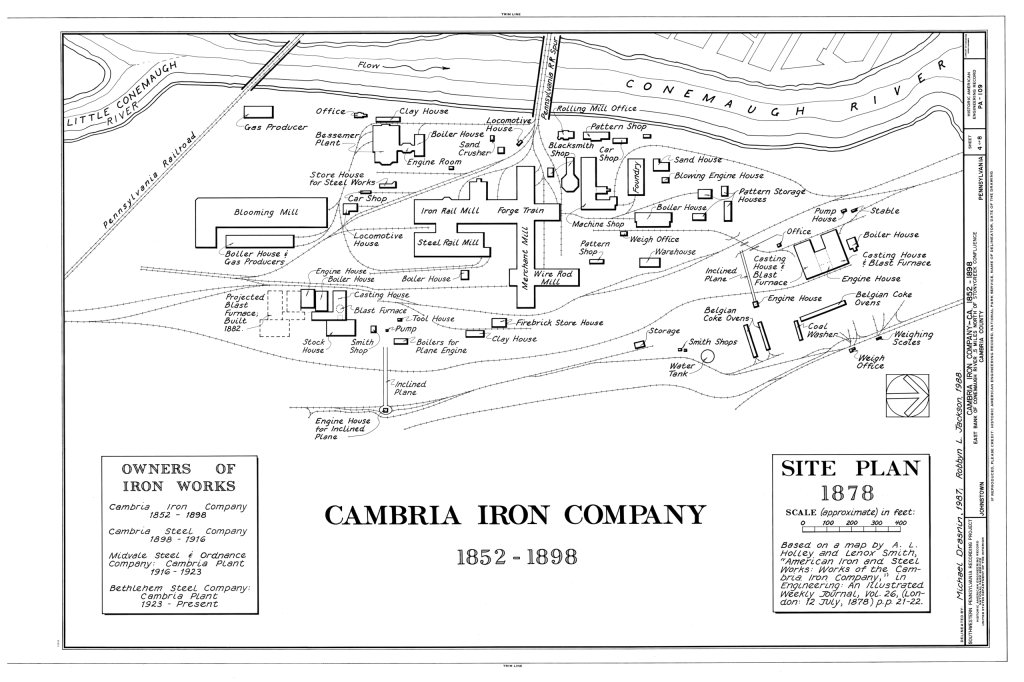

Considered a technological marvel in its day and critical to opening the way to commerce and settlement past the Appalachian Mountains, the original Allegheny Portage Railroad consisted of a series of five inclines on either side of the ridge-line from Blair Gap to Cresson Summit alongside what is called the Little Conemaugh River to where it meets the Conemaugh River at Johnstown.

Interesting things to note that along the historic route of the Allegheny Portage Railroad are as follows:

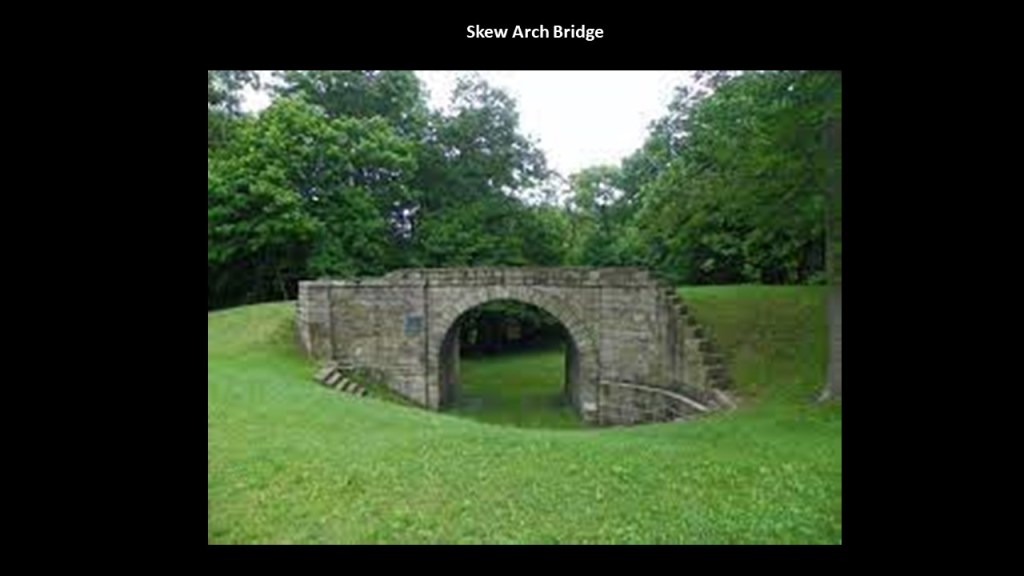

After leaving the main canal location of Hollidaysburg and going up towards Cresson Summit, we first come to the lopsided-looking “Skew Arch Bridge,” called the “only purposefully built bridge on the Portage” and crossed over the railway.

The “Skew Arch Bridge” was said to have been built in the 1830s, and was also part of the early road system, said to have gotten its name for its shape when it was being built from a bend in the “Huntington, Cambria, and Indiana Turnpike” which was said to have been first authorized in 1810.

Today, the “Skew Arch Bridge” is preserved in the middle of “Old U. S. Route 22” and the new “U. S. Route 22.”

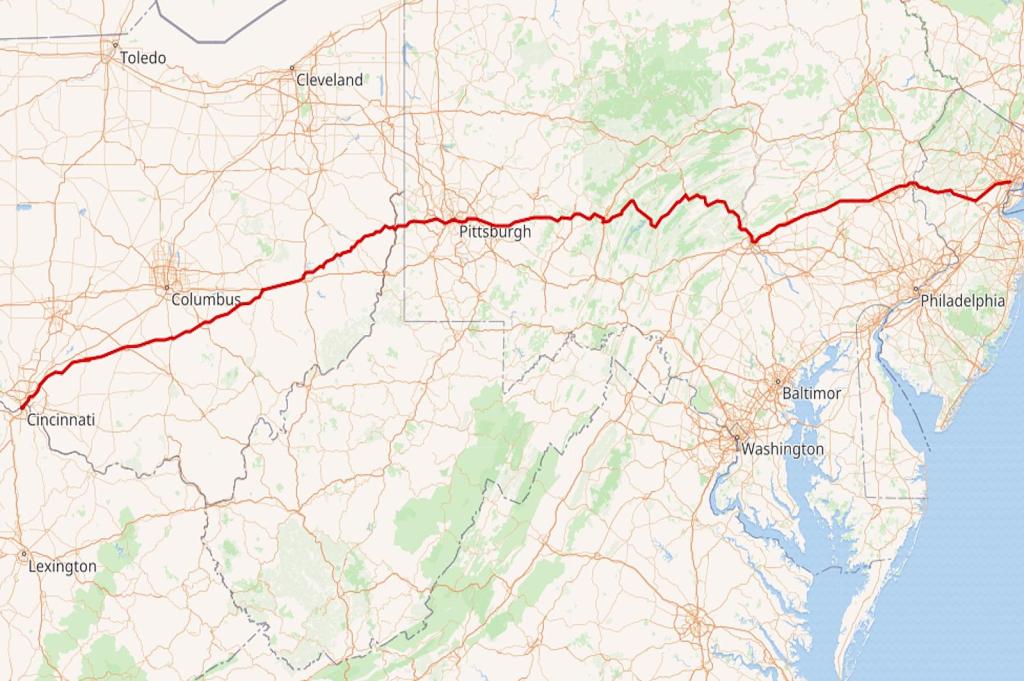

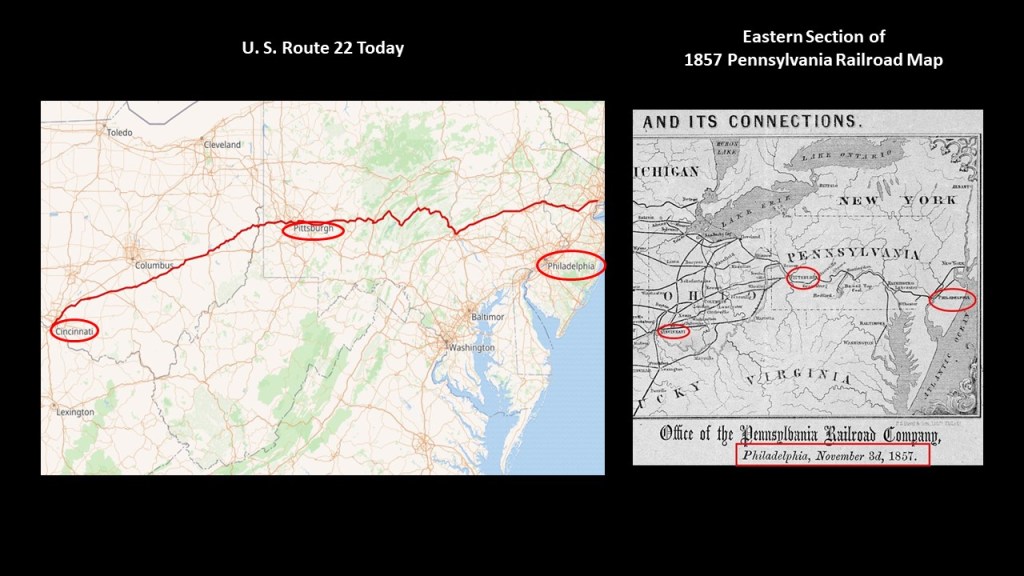

U. S. Route 22 is an East-West Numbered Highway from 1926 that runs from Cincinnati in Ohio to Newark in New Jersey, and passes through West Virginia and Pennsylvania on the way.

In Pennsylvania, U. S. 22 follows the route of the historic William Penn Highway, which was officially dedicated on November 15th of 1916, that ran parallel to the Pennsylvania Railroad through most of Pennsylvania.

First established in 1846, at its peak in 1882 , the Pennsylvania Railroad was the largest railroad, transportation enterprise, and corporation in the world.

This map of the extent of the Pennsylvania Railroad was dated November 3rd of 1857, which would have been four-years before the start of the American Civil War.

But seeing a side-by-side comparison of these two maps, it certainly appears as though most of US-22 is on or right next to what used to be the main railroad line for the Pennsylvania Railroad.

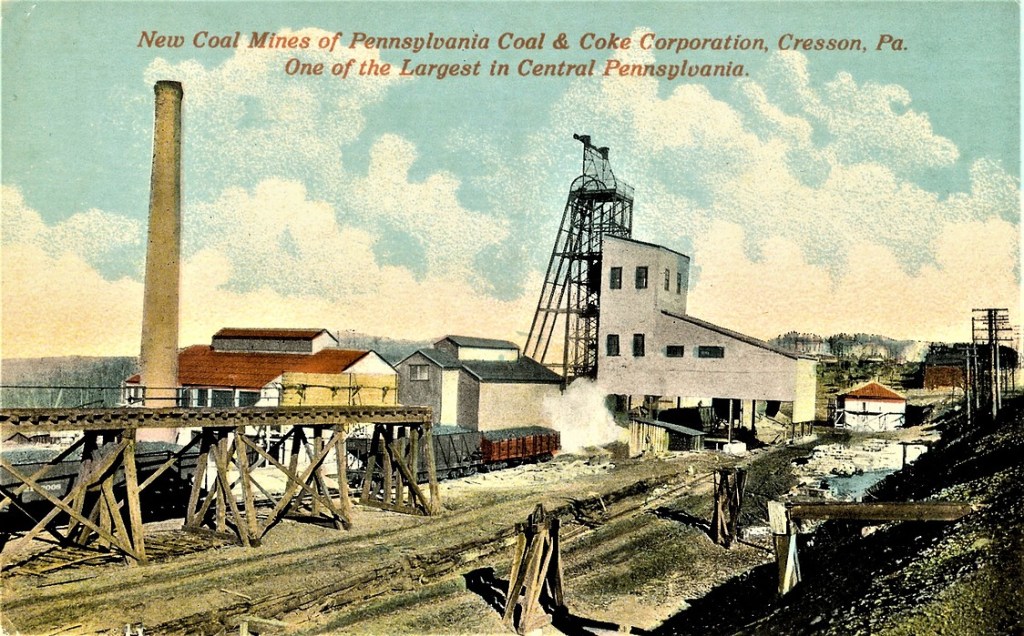

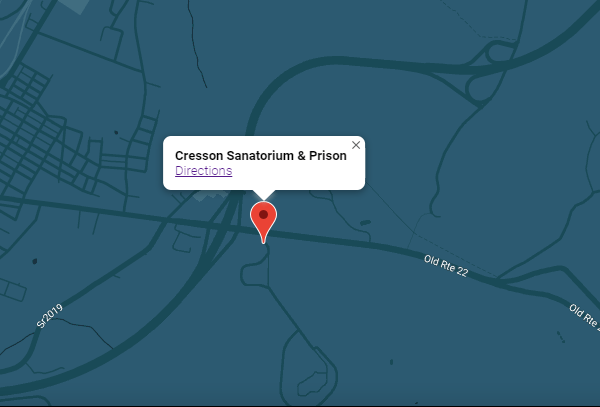

The next landmark n the Allegheny Portage Railroad’s journey through the Allegheny Mountains is the summit at Cresson, a borough (which in Pennsylvania is a municipal entity like a town or small city) on top of the Eastern Continental Divide.

US Route 22 is one of the highways that accesses Cresson.

Back in the industrial heyday of the late 19th-century and early 20th-century, there were lumber, coal and coke-yard industries located here.

Wealthy Pittsburgh businessmen like Andrew Carnegie, Henry Clay Frick and Charles Schwab, all connected to each other through the steel industry, had summer residences here, like Carnegie’s Braemar Cottage in Cresson.

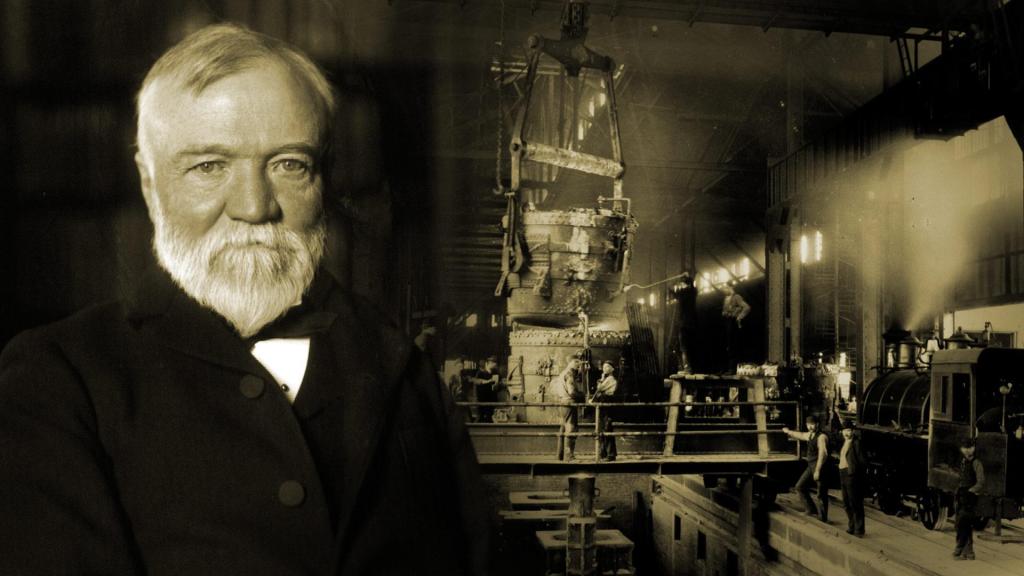

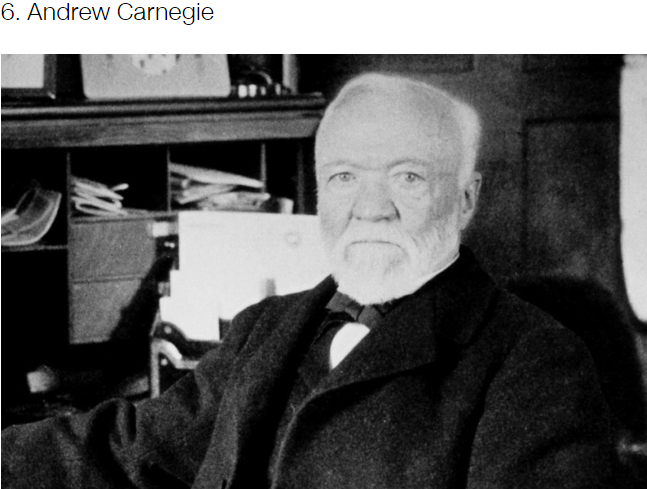

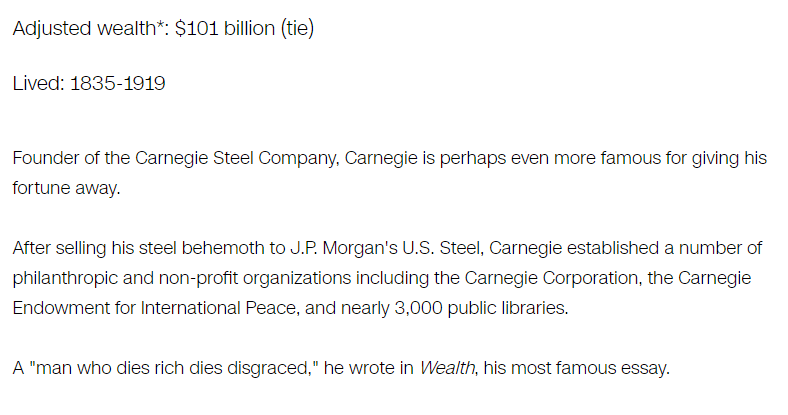

Andrew Carnegie was a Scottish immigrant to America, who came to Pittsburgh in 1848 with his parents at the age of 12, got his start as a telegrapher, and who by the 1860s, had investments in such things as railroads, bridges and oil derricks, and ultimately worked his way into being a major player in Pittsburgh’s steel industry.

I couldn’t find a picture of Andrew Carnegie as a freemason, but I could find a reference to him being a “famous freemason” on a masonic website.

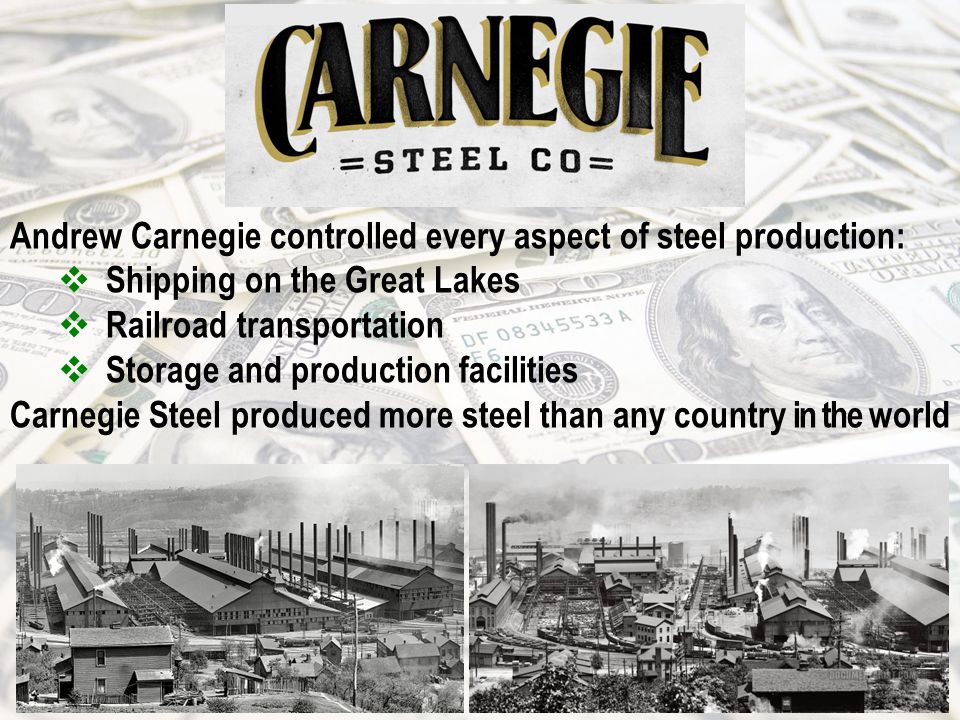

His first steel mill was operational by 1874, the Edgar Thomson Steel Works, named after the President of the Pennsylvania Railroad, with his partners, one of whom was Henry Clay Frick, the owner of a coke manufacturing company, a product used in making steel.

They subsequently acquired other steel mills, and in 1892, the Carnegie Steel Company was formed, of which Henry Clay Frick became chairman. and in 1897, Charles M. Schwab, who had gotten his start as an engineer at the Edgar Thomson Steel Works, became President of the Carnegie Steel Company in 1897.

In 1901, Charles M. Schwab helped negotiate the sale of Carnegie Steel with a merger involving it with Elbert Gary’s Federal Steel Company, and William Henry Moore’s National Steel Company in 1901 to a group of New York City Financiers led by J. P. Morgan.

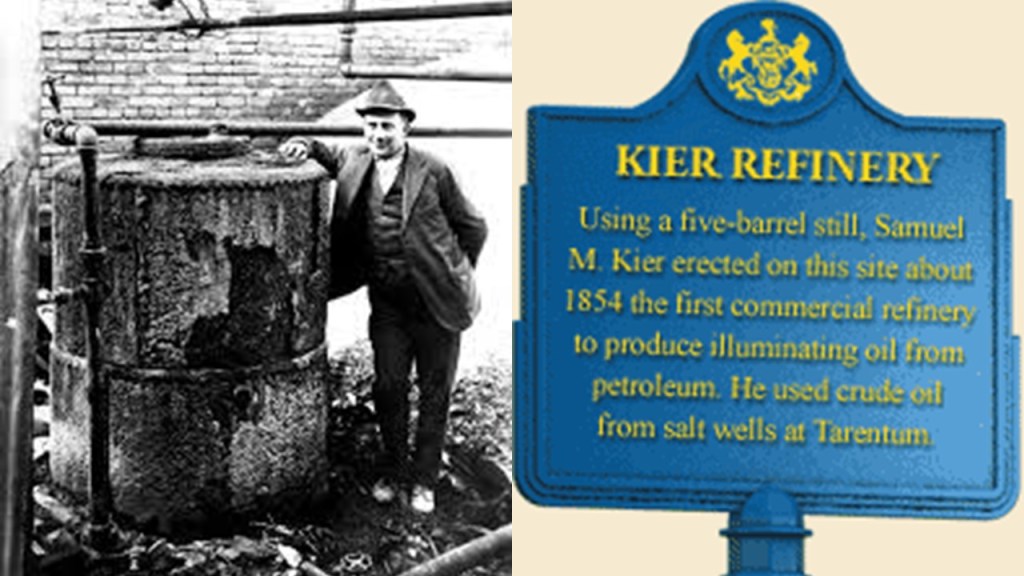

After the sale of Carnegie Steel, Andrew Carnegie surpassed John D. Rockefeller as the richest American of the time, and Charles M. Schwab became the first President of the newly minted U. S. Steel Company.

Now back to Cresson.

Cresson was known for its therapeutic mineral springs, and we are told that in 1881, the Pennsylvania Railroad opened the Mountain House Resort Hotel.

Carnegie’s Braemar Cottage is still standing on the 400-acre property, which had 32-lots for private-cottages.

Alas for the Mountain House Resort Hotel and Cresson Springs, just like canals falling by the wayside for railroads, and railroads the same for automobiles, America’s appetite for “mountain” or “inland” resorts began to decline in favor of beach resorts.

The Mountain House Resort Hotel had ceased operations by the early 1900s, and in 1916, it was completely razed to the ground, and the original hotel building was gone.

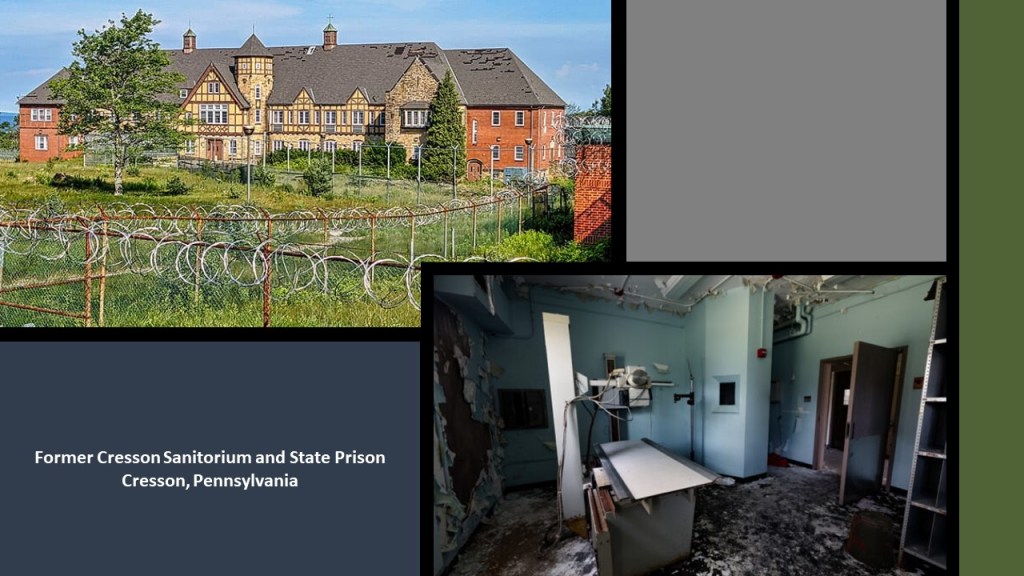

Interesting to note, that unlike the luxurious Mountain House Resort Hotel that got razed to the ground, the likewise spacious building of the former Cresson Sanitorium and Prison is still-standing, albeit in pretty rough shape these days!

This is what we are told.

Cresson Sanitorium was built on land that was donated by Andrew Carnegie in 1910, and first opened in 1913 in order to provide hospital and long-term care facilities for individuals and families with tuberculosis and other health conditions.

In 1956, it was incorporated into the Lawrence F. Flick State Hospital for people with mental illness.

In 1983, it was converted to a State Correctional Facility, and operated as such for the next 30-years, until its final closure in 2013.

The building is located on Old Route 22.

The former sanitorium and prison has been operating as a tourist attraction, but is closed pending outcome of a legal battle and hoping to reopen.

This site is known for its paranormal activity of the ghostly sort.

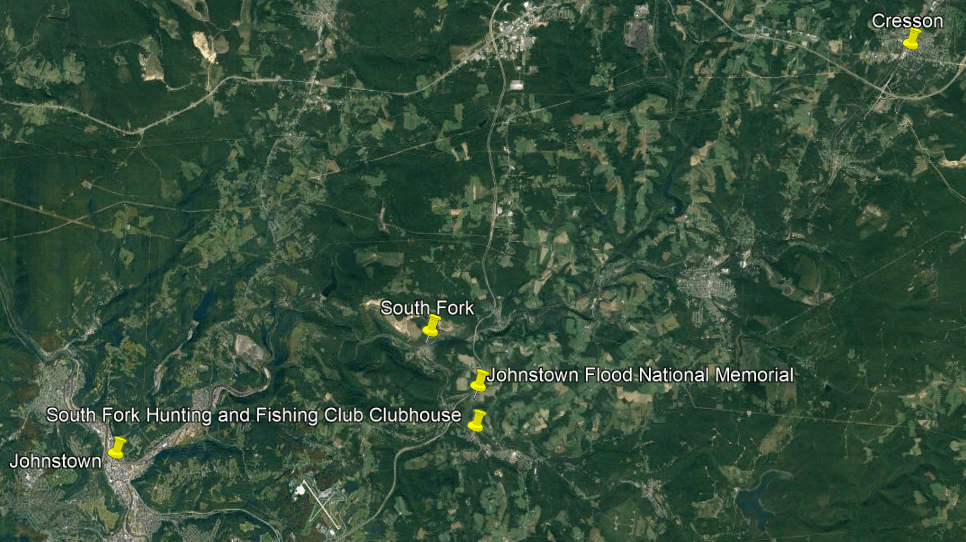

After the former Allegheny Portage Railroad left the summit at Cresson, on its downward descent in elevation into Johnstown, along the Little Conemaugh River, we come to South Fork of the Little Conemaugh River and what was the former location of the South Fork Dam.

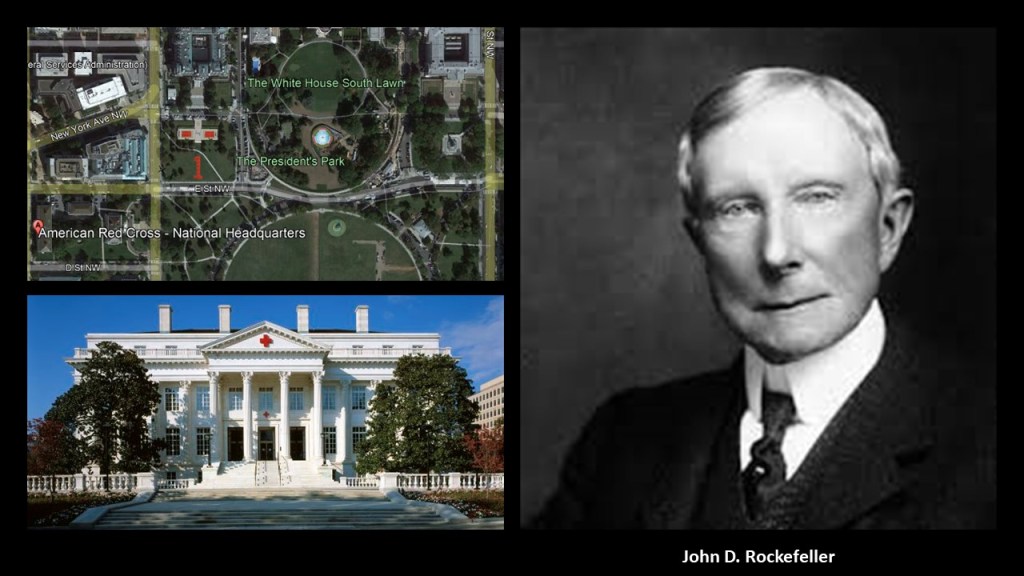

The famous Johnstown Flood on May 31st of 1889, the worst flood in the United States in the 19th-century, was caused by the catastrophic failure of the South Fork Dam, and was the second major disaster the American Red Cross responded to, after the Michigan Thumb Fire, which started on September 5th of 1881, with hurricane-force winds and hot and dry conditions this was less than four months after the establishment of the American Red Cross in May of 1881.

John D. Rockefeller was amongst several that donated to create a national headquarters for the American Red Cross near the White House in Washington, DC, said to have been built between 1915 and 1917.

The South Fork Dam was said to have been an earthwork built between 1838 and 1853 as part of a canal system as a reservoir for a canal basin in Johnstown by the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania.

But then, after spending 15-years building the dam, it was abandoned by the Commonwealth, and sold to the Pennsylvania Railroad, who turned around and sold it to private interests.

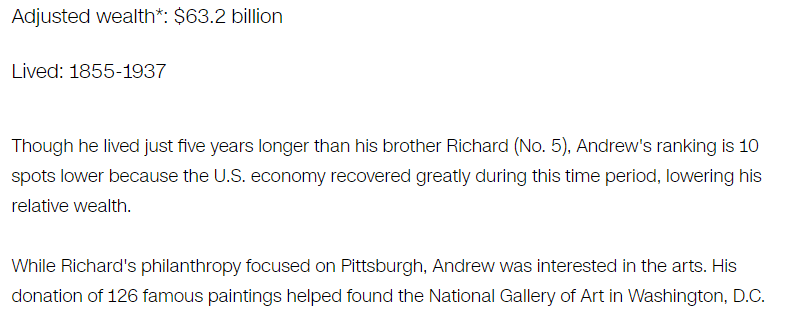

In 1881, speculators had bought the abandoned reservoir and built a clubhouse called the South Fork Fishing and Hunting Club and cottages, turning it into an exclusive retreat for 61 steel and coal financiers from Pittsburgh, including Andrew Carnegie, Henry Clay Frick, Andrew Mellon, Philander Knox, John Leishman, and Daniel Johnson Morrell.

The South Fork Fishing and Hunting Club was a Pennsylvania Corporation and owned the South Fork Dam.

Henry Clay Frick was a founding member of the South Fork Fishing and Hunting Club, and was actually said to have been largely responsible for the alterations to the South Fork Dam that led to its failure.

Interesting to note that I did find this reference on the website of the Pleasant Valley Masonic Center in Connellsville, Pennsylvania, that Henry Clay Frick was a freemason in its King Solomon’s Lodge #346 from 1872 to 1877 , at which time he resigned as an active mason, but from what this entry says, his masonic lodge continued to enjoy the benefits of his generosity long afterwards, as well as that of his daughter.

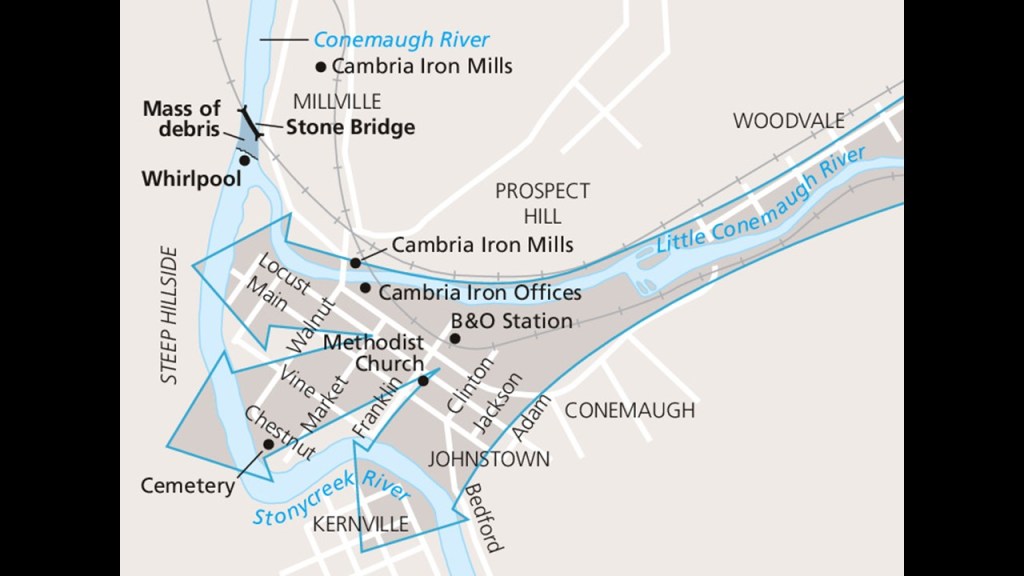

What we are told is that the South Fork Dam failed after days of unusually heavy rain, and 14.3-million-tons of water from the reservoir of Lake Conemaugh devastated the South Fork Valley, including Johnstown 12-miles, or 19-kilometers, downstream from the dam, killing an estimated 2,209 people and causing $17-million in damages in 1889, which be $490-million in 2020.

Though there were years of claims and litigation, the elite and wealthy members of the South Fork Fishing and Hunting Club were never found liable for damages.

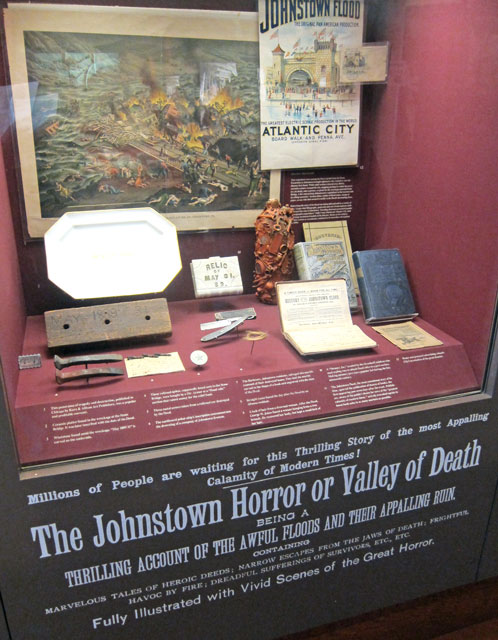

In 1904, the South Fork Fishing and Hunting Club corporation was disbanded and assets sold at a public auction by the sheriff, and there were permanent exhibits in many places, like Atlantic City, depicting the horrors of the Johnstown Flood experience for public consumption, billed as a “Thrilling Account of the awful floods and their appalling ruin.”

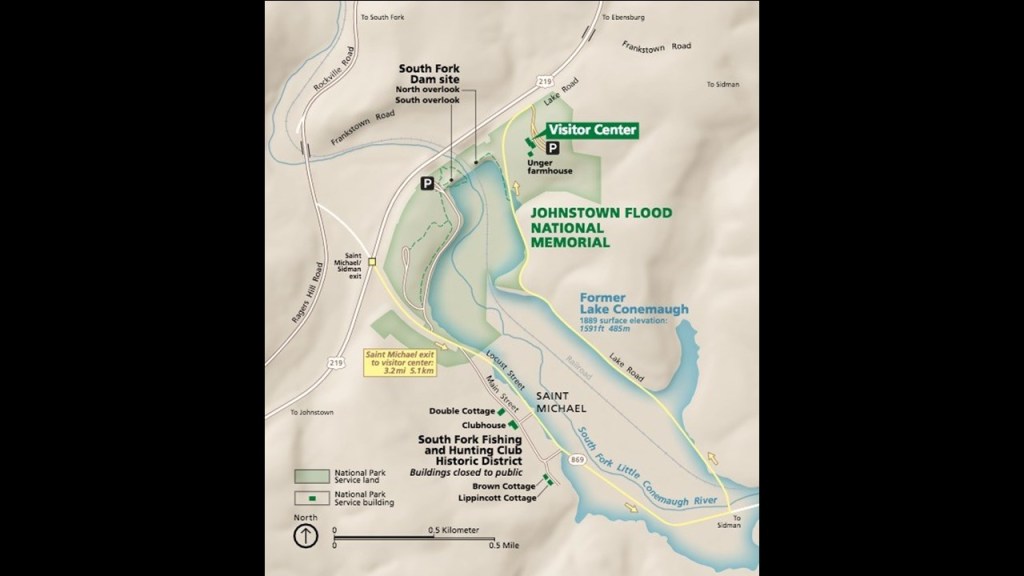

The South Fork Fishing and Hunting Club building and the nine-remaining of sixteen club member cottages still stand today, and are under the auspices of the National Park Service as part of the Johnstown Flood National Memorial.

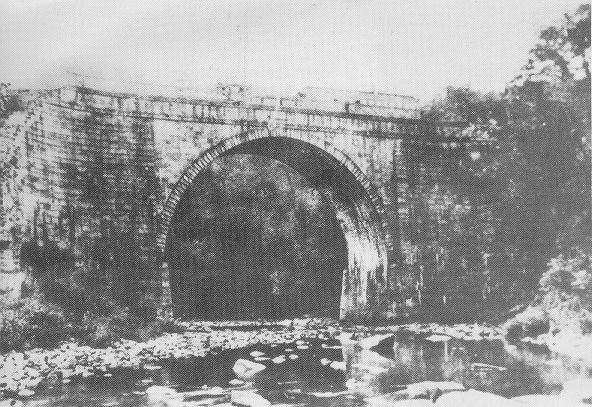

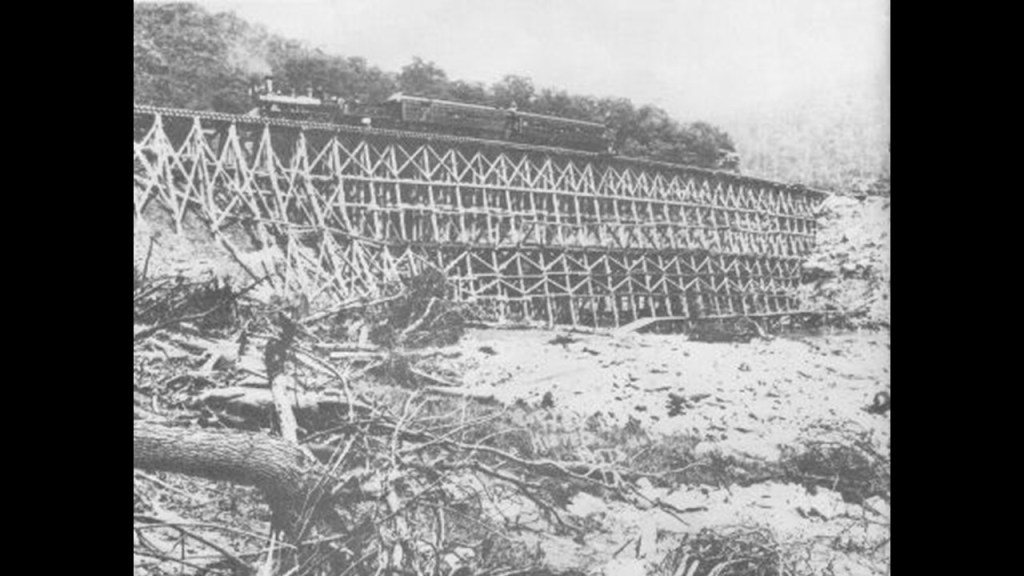

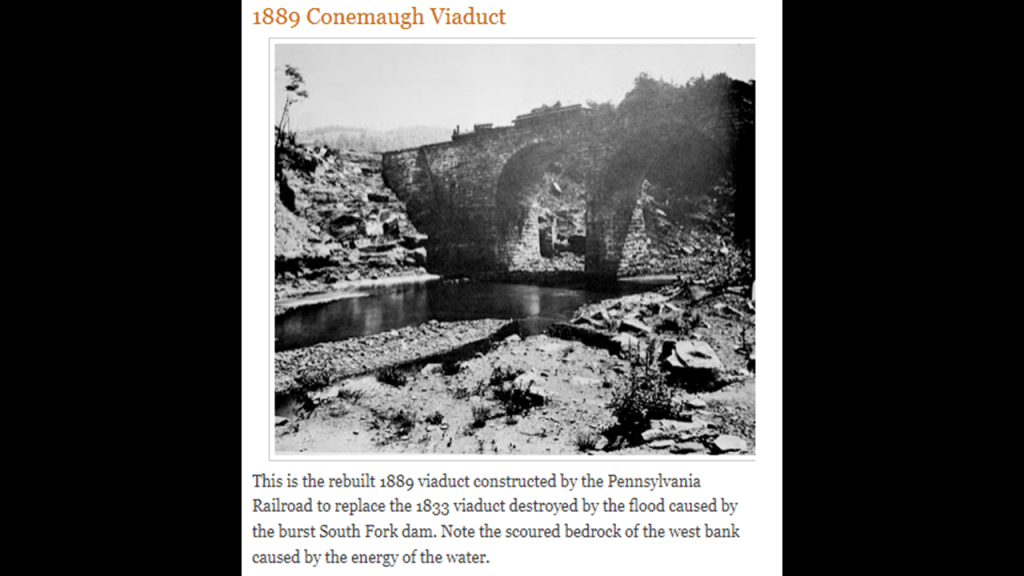

The Conemaugh Viaduct was located between the South Fork Dam and Staple Bend Tunnel on the descent into Johnstown.

This is what we are told in the official narrative about what happened here.

The Conemaugh Viaduct was originally built in 1833 as part of the Allegheny Portage Railroad where it crossed the Little Conemaugh River, and that it was often described as the most beautiful railroad bridge in the world.