In the last part of this series, I looked at who represents the states of Louisiana, Maine, Maryland and Massachusetts in the National Statuary Hall at the U. S. Capitol in Washington, DC.

Louisiana is represented by attorney, Governor & Senator Huey P. Long and by attorney and Supreme Court Justice Edward Douglass White; Maine by attorney and Vice-President of the United States, Hannibal Hamlin & merchant and first Governor of Maine, William R. King; Maryland by politician and Founding Father Charles Carroll of Carrollton and John Hanson, Founding Father, politician and first President of the Confederation Congress during the Second Continental Congress of 1781; and Massachusetts by Samuel Adams, a politician called the “Father of the American Revolution,” and John Winthrop, an English Puritan lawyer, who led the first wave of colonists from England in 1630, a leader in establishing the Massachusetts Bay Colony, and its first Governor.

So far the count of politicians in the National Statuary Hall is at 26-out-of-42 statues, once again over half of them, with seventeen of the politicians being lawyers.

There are also interconnections between these historical figures in the National Statuary Hall, as you shall see.

Let’s see who and what comes up next!

The State of Michigan is represented by Lewis Cass and Gerald Ford in the Statuary Hall.

Lewis Cass, an American military officer, politician and statesman, was a U. S. Senator for Michigan and served in the cabinets of two Presidents, Andrew Jackson and James Buchanan.

Cass was born in October of 1782 in Exeter, New Hampshire, near the end of the Revolutionary War.

His father Jonathan was an officer who had fought under George Washington at the Battle of Bunker Hill which took place in June of 1775.

This illustrated view of the Bunker Hill Monument was circa 1848, and said to have been built between 1824 and 1843, and credited to the architect Solomon Willard as the first monumental obelisk erected in the United States.

Cass attended the Phillips-Exeter Academy, established in 1781 by Elizabeth and John Phillips, a wealthy merchant and banker of the time.

His nephew, Samuel Phillips Jr, had established the Phillips Academy in Andover, Massachusetts in 1778, making it the oldest incorporated school in the United States.

These two schools have educated several generations of the Establishment and prominent American politicians.

The Cass family moved to Marietta, Ohio, in 1800.

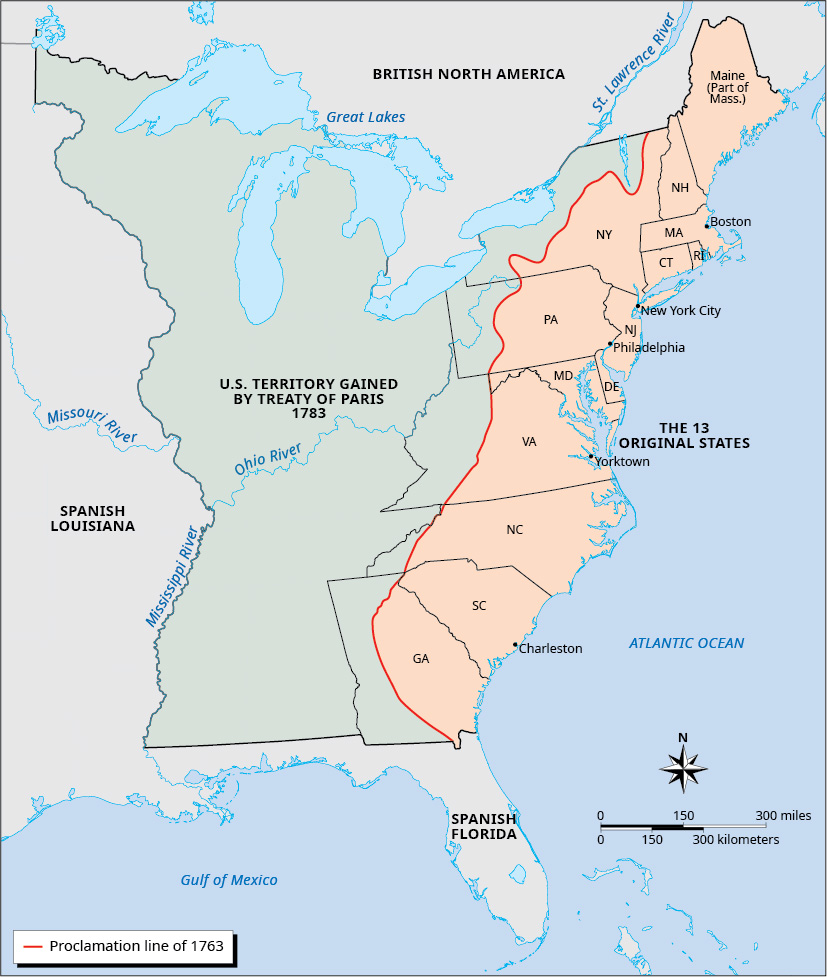

Marietta was the first permanent U. S. settlement in the newly established Northwest Territory, which was created in 1787, and the nation’s first post-colonial organized incorporated territory.

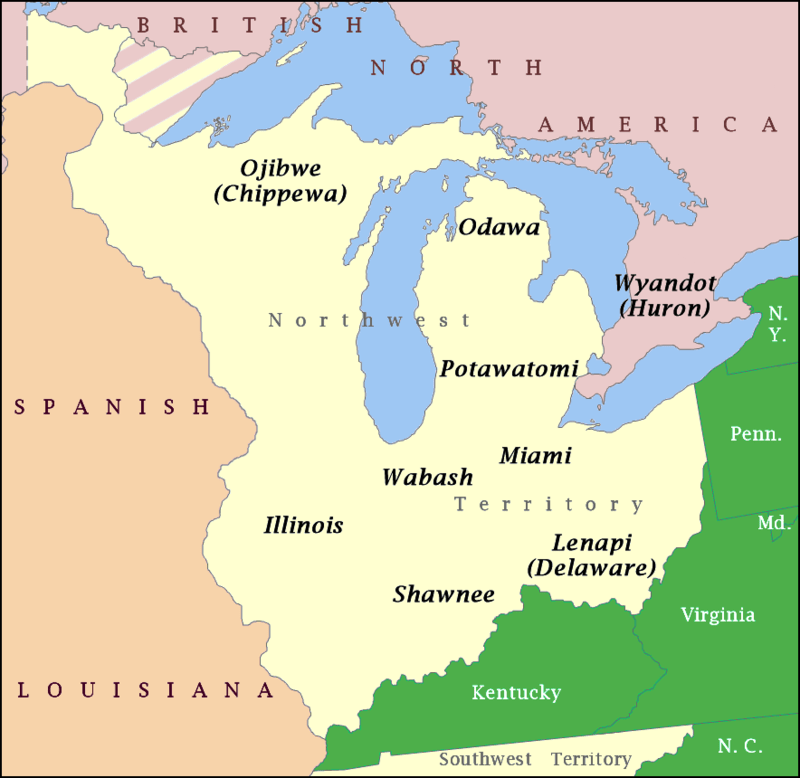

The Northwest Indian War took place in this region between 1786 and 1795 between the United States and the Northwestern Confederacy, consisting of Native Americans of the Great Lakes area.

The Territory had been granted to the United States by Great Britain as part of the Treaty of Paris at the end of the Revolutionary War.

The area had previously been prohibited to new settlements, and was inhabited by numerous Native American peoples.

The British maintained a military presence and supported the Native American military campaign.

While the Northwestern Confederacy had some early victories, they were ultimately defeated, with the final battle being the “Battle of Fallen Timbers” in August of 1794 in Maumee, Ohio, which took place after General Anthony Wayne’s Army had destroyed every Native American settlement on its way to the battle.

Outcomes were the 1794 Jay Treaty, named for Supreme Court Chief Justice John Jay, the main negotiator with Great Britain.

As a result, the British withdrew from the Northwest Territory, but it laid the groundwork for later conflicts, not only with Great Britain, but also angering France and bitterly dividing Americans into pro-Treaty Federalists and anti-Treaty Jeffersonian Republicans.

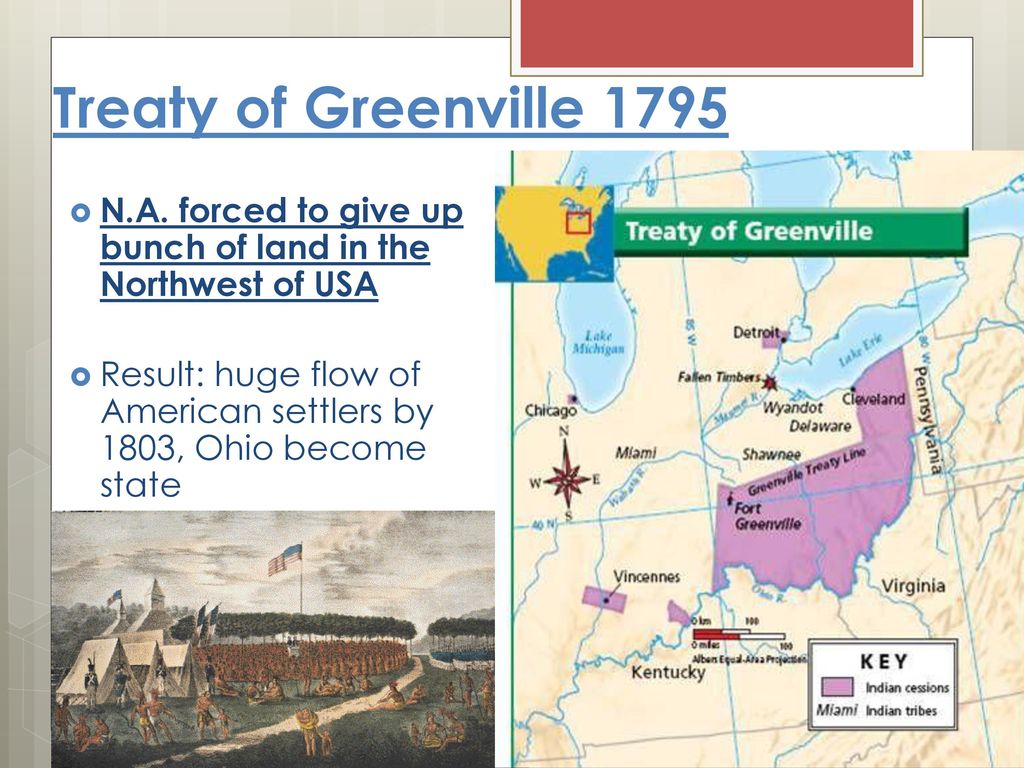

The 1795 Greenville Treaty that followed forced the displacement of Native Americans from most of Ohio, in return for cash and promises fair treatment, and the land was opened for white American settlement.

Lewis Cass studied law in Marietta under Return Meigs, Jr, who among other accomplishments, became the first Chief Justice of the Ohio Supreme Court in 1803, and Cass started his law practice in Zanesville, Ohio.

Cass was elected to the Ohio House of Representatives in 1806, and the following year, President Thomas Jefferson appointed him as the U. S. Marshal for Ohio, the oldest U. S. Federal Law Enforcement Agency having been established by the Judiciary Act of 1789 during President George Washington’s administration to assist federal courts in their law enforcement functions.

Cass joined the Freemasons as an Entered Apprentice, the first degree of Freemasonry, at a lodge in Marietta in 1803 , and by May of 1804, he achieved the Master Mason degree, the third-degree of Freemasonry.

He was a charter member of the Lodge of Amity No. 5 in Zanesville, admitted in June of 1805…

…and was one of the founders of the Grand Lodge of Ohio in January of 1808, serving as its Grand Master multiple years.

During the War of 1812, Cass rose through the officer ranks to become a Brigadier General in the U. S. Army in March of 1813.

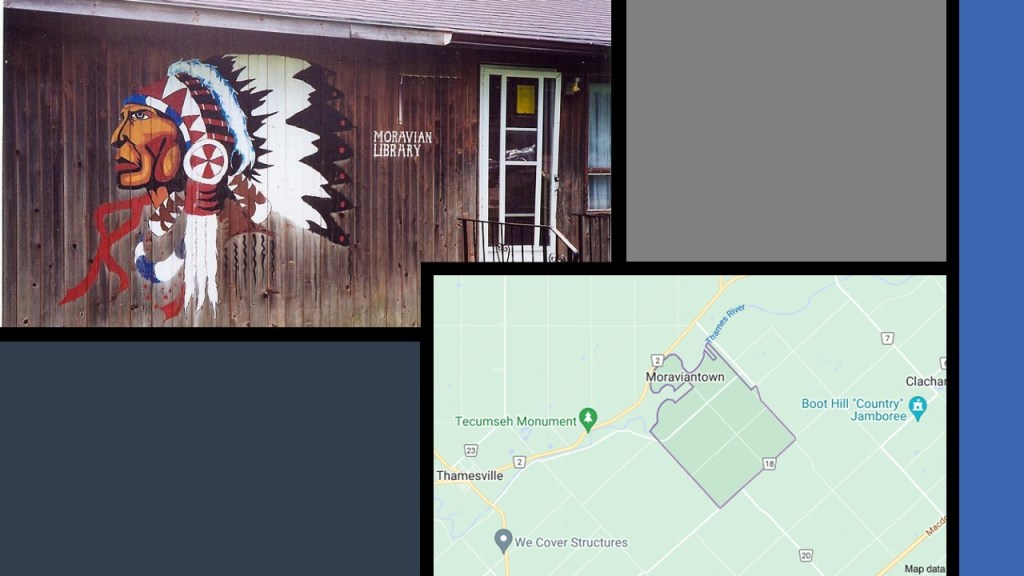

He took part in the Battle of the Thames, also known as the Battle of Moraviantown near Chatham, Ontario, and today’s Moravian on the Thames First Nation reserve, a branch of the Lenape who were converted to Christianity by Moravian missionaries from Pennsylvania, one of the oldest Protestant denominations.

At the time of the battle, the community of this First Nation, known as the Christian Munsee, was burned to the ground and rebuilt at its current location.

The Battle of the Thames in Ontario was an American victory in the War of 1812 against Tecumseh’s Confederacy, a confederation of Native people’s from the Great Lakes region, and their British allies.

As a result of the battle, Tecumseh was killed, his confederacy fell apart, and the British lost control of southwestern Ontario.

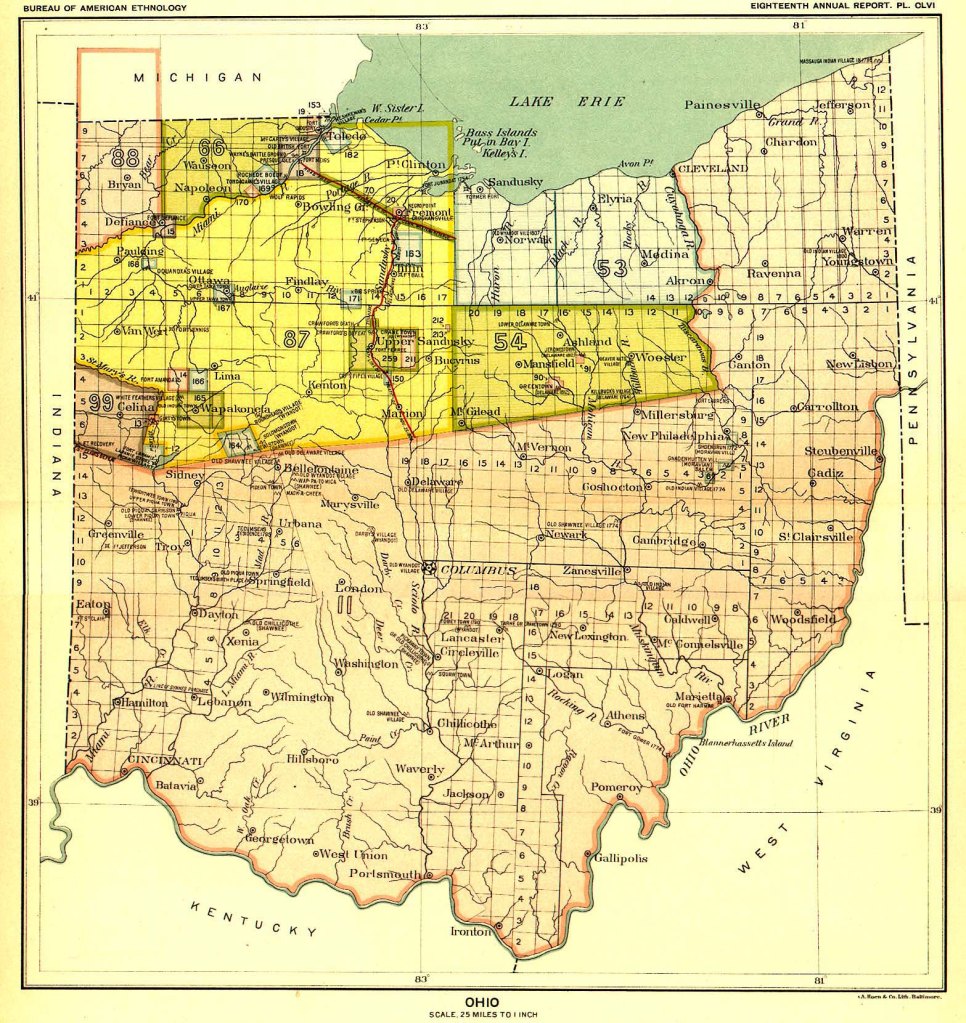

Cass was appointed as the Governor of the Michigan Territory by President James Madison in October of 1813, a position in which he served until 1831.

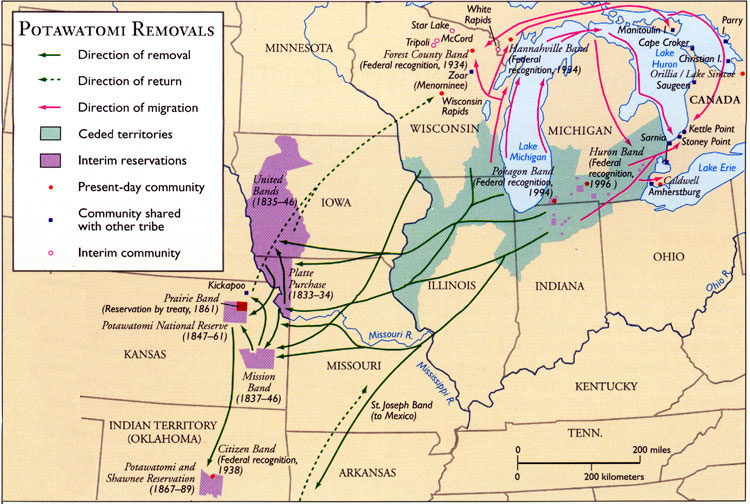

During this time, he travelled frequently to negotiate treaties with Native American tribes in Michigan, in which they ceded substantial amounts of land.

Cass was one of two commissioners who negotiated the Treaty of Fort Meigs, also called the Treaty of the Maumee Rapids, resulting the ceding of nearly all the remaining lands in northwestern Ohio, and parts of Indiana and Michigan, of the Wyandot, Seneca, Delaware, Shawnee, Potawatomi, Ottawa, and Chippewa, helping to open up Michigan to settlement by white Americans.

In return, land was allocated for reservations and financial compensation via annuities of various amounts for different lengths of time.

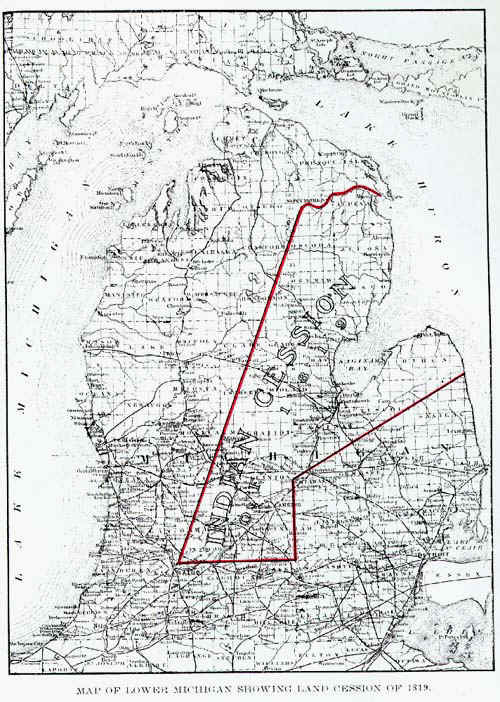

Other examples of the involvement of Lewis Cass with these land-acquiring treaties included, the 1819 Treaty of Saginaw with the chiefs and members of the Chippewa, Ottawa, and Potawatomi Tribes, in which they ceded 6-million acres of land, for which they were promised up to $1,000/year forever, and hunting and fishing rights on the land.

Cass was also involved with the 1821 Treaty of Chicago, in which he travelled to Chicago to try and get more land from tribal nations in Michigan.

As a result of this treaty, more Potawatomi, Chippewa and Ottawa tribes ceded land – this time nearly 5-million acres of the Lower Peninsula .

In return, they were promised about $10,000 in trade goods, $6,500 in coins, and a 20-year payment valued at about $150,000.

And where did all these treaties land them, like the Potawatomi?

A very long way from home!!!

Cass resigned as the Governor of Michigan in 1831 to become President Andrew Jackson’s Secretary of War, a position he would hold for the next 5-years.

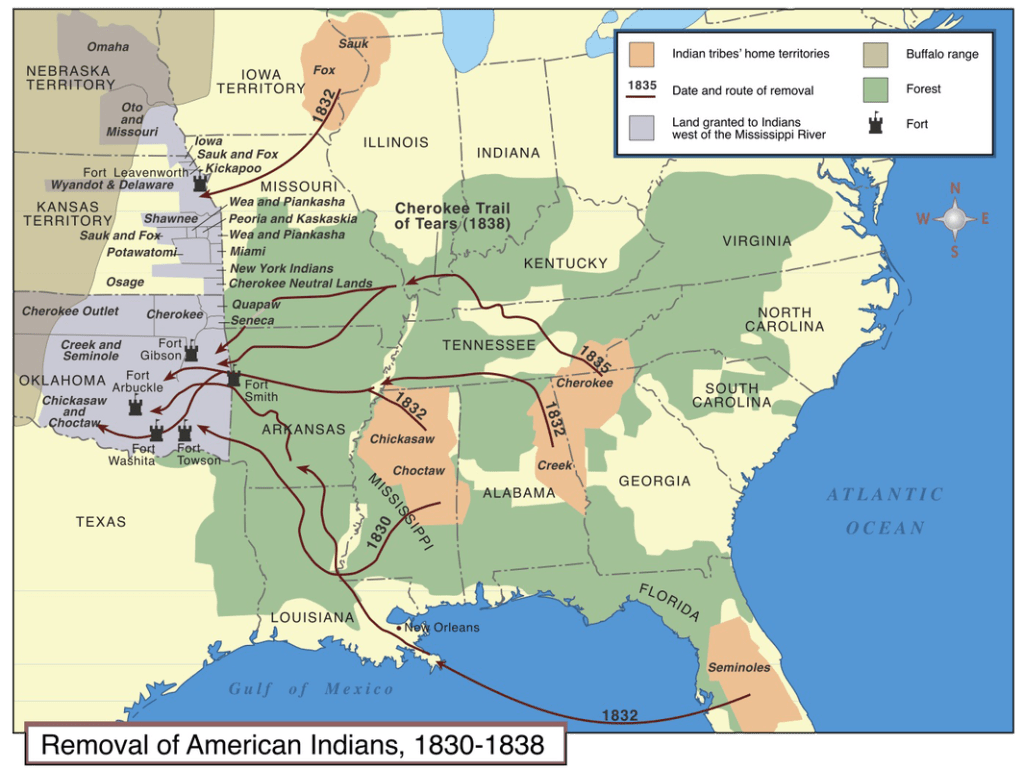

As President Jackson’s Secretary of War, Cass was central in implementing the Indian Removal policy of the Jackson administration after Congress passed the Indian Removal Act in 1830.

The Indian Removal Act was directed specifically at the Five Civilized Tribes of the Southeastern United States – the Cherokee, Creeks, Seminole, Chickasaw and Choctaw – though it also affected tribes in Ohio, Illinois and other areas east of the Mississippi River.

Most were forced to Indian Territory in present-day Oklahoma, Kansas, and Nebraska.

Cass was appointed as the U. S. Minister to France by President Jackson, starting in 1836, and he held this position until 1842.

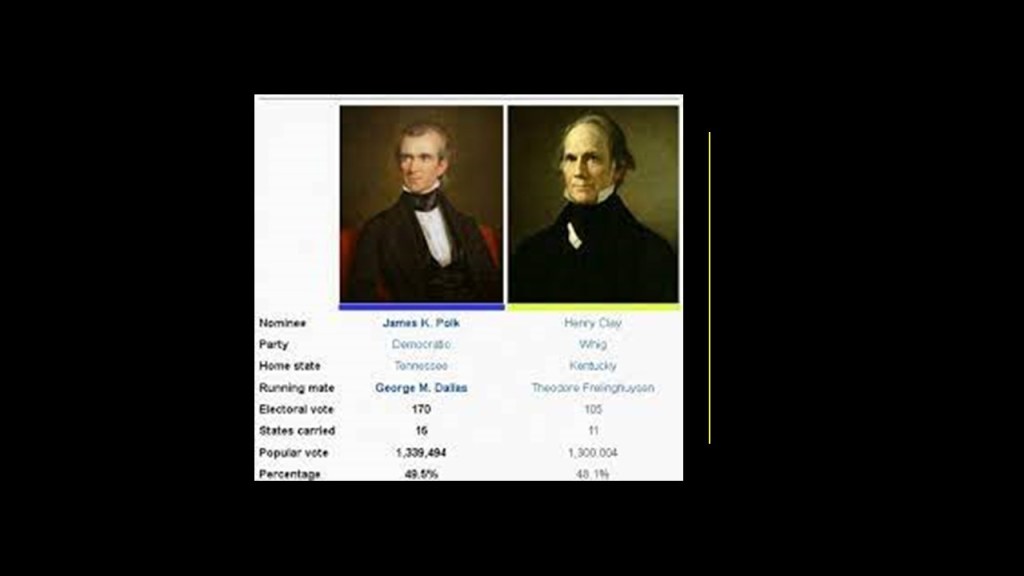

Then in 1844, Cass stood as a Democratic candidate for the Presidential nomination, but lost the nomination that year to James Polk, who defeated the Whig candidate Henry Clay to became the 11th President of the United States, serving from 1845 to 1849.

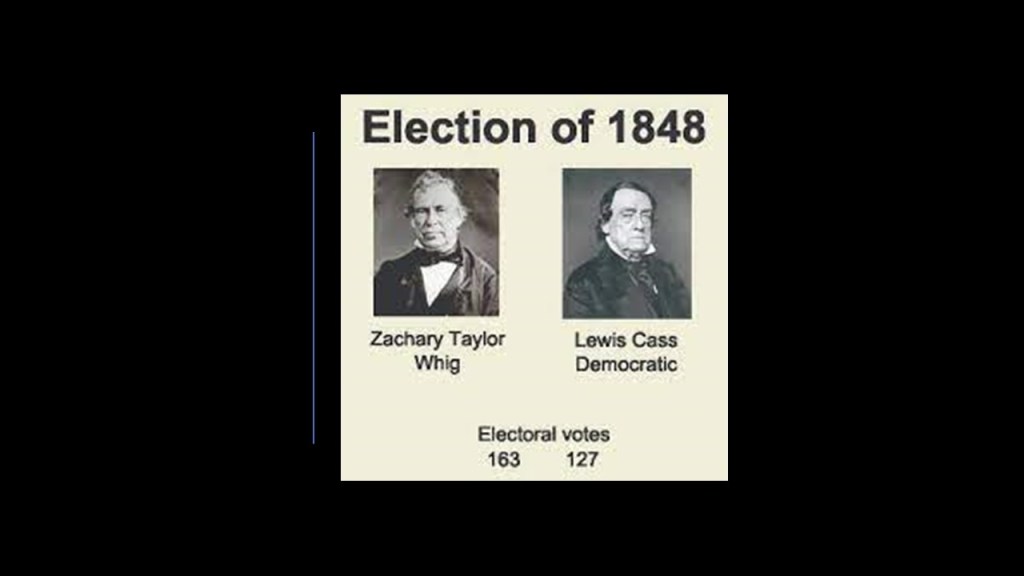

Cass was then elected by the Michigan State Legislature in 1845 to serve as its United States Senator, a position he held until 1848 when he resigned in order to pursue an unsuccessful run for President that year.

He was a leading supporter of the Popular Sovereignty doctrine, which held that the American citizens of a territory should decide whether or not to permit slavery there as a middle position on the slavery issue.

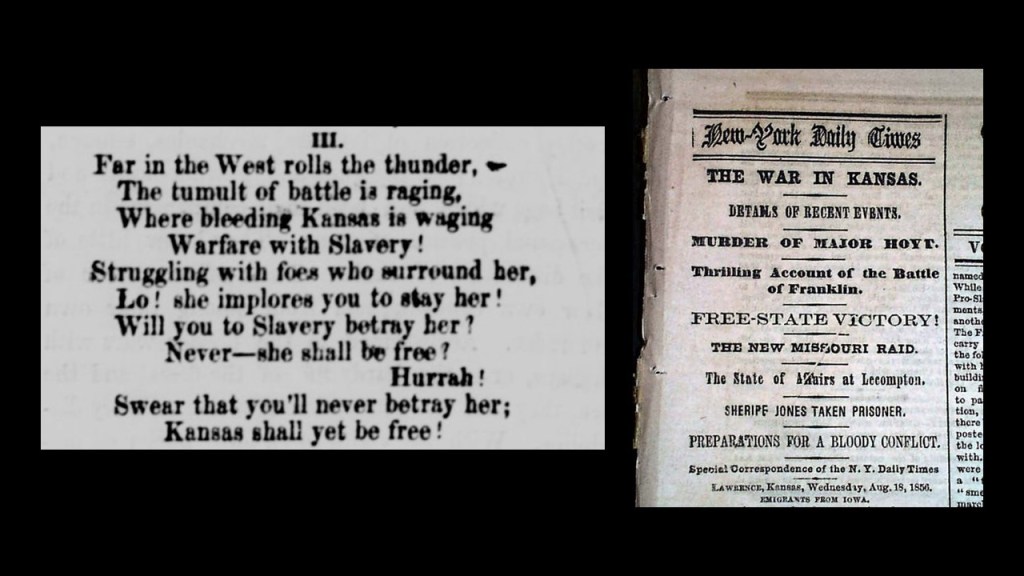

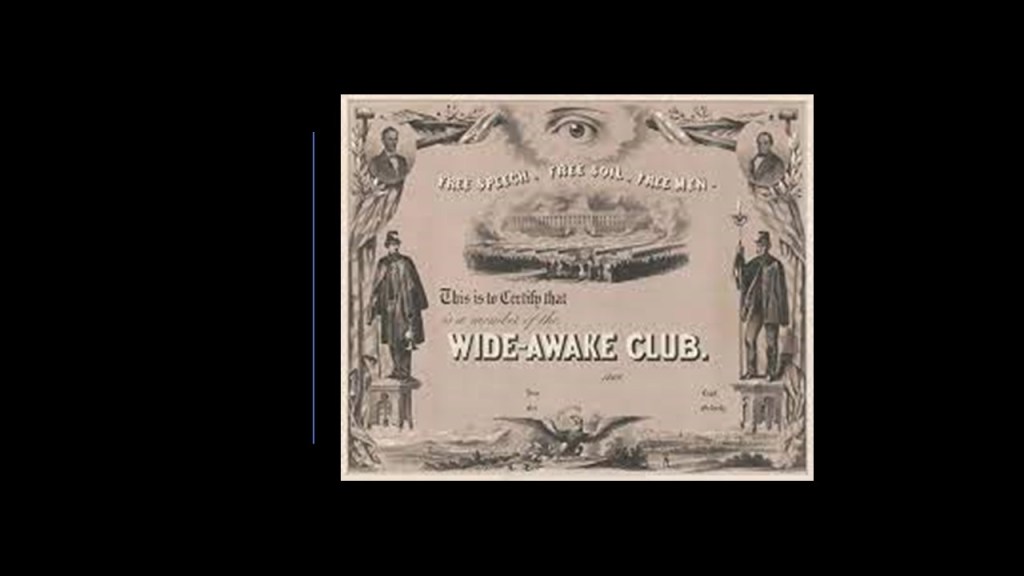

Popular sovereignty was applied in the Kansas-Nebraska Act, which passed Congress in 1854, but was most notable for stoking national tensions over slavery on the road to the American Civil War and leading to “Bleeding Kansas,” a series of violent confrontations between 1854 and 1859 over a political and ideological debate over the legality of slavery in the Proposed state of Kansas.

After his loss to Zachary Taylor in the 1848 election, Cass was returned to the

U. S. Senate by the Michigan State Legislature, serving from 1849 to 1857.

He ran and lost for President a third-time in 1852, losing the Democratic nomination that year to Franklin Pierce, who became the 14th U. S. President.

A few years later, in March of 1857, President James Buchanan appointed an elderly Lewis Cass to serve as the Secretary of State in his administration around the same time he was retiring from the Senate.

During his term of service as Secretary of State, Cass delegated most of his responsibilities either to an Assistant Secretary of State or to the President, though he was involved in negotiating a final settlement to the 1850 Clayton-Bulwer Treaty, which limited U. S. and British control of Latin American Countries.

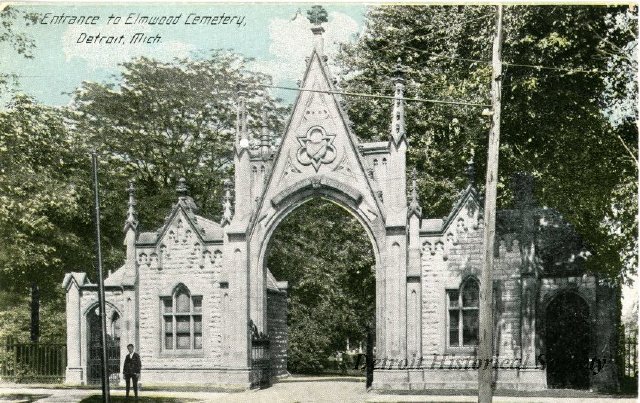

Cass died in June of 1866 in Detroit, and was buried in the Elmwood Cemetery in Detroit, Michigan’s oldest continuously operating non-denominational cemetery, having been dedicated in October of 1846.

Interesting to see so many classical-looking stone masonry tombs in Elmwood that are entombed in the earth surrounding them.

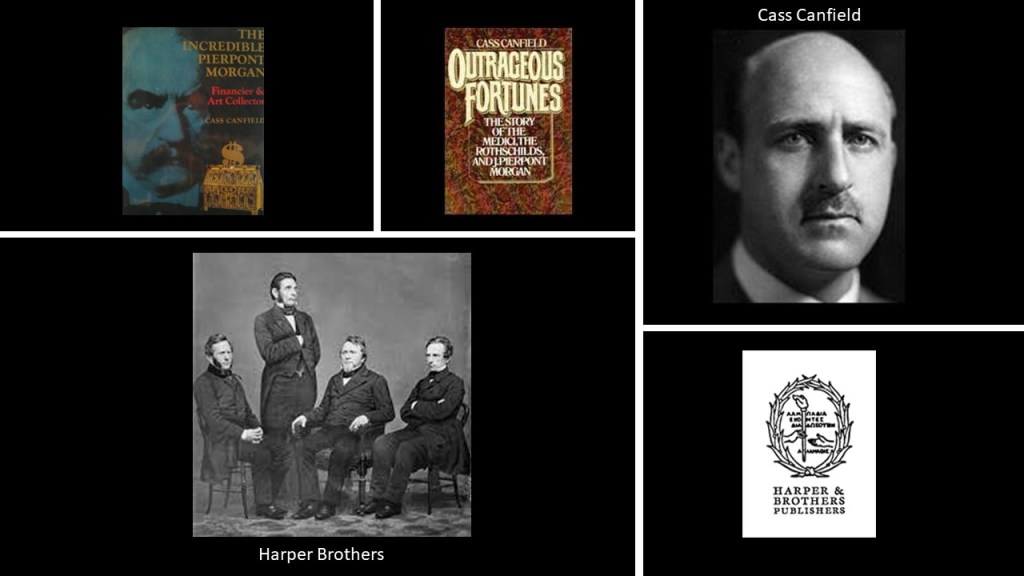

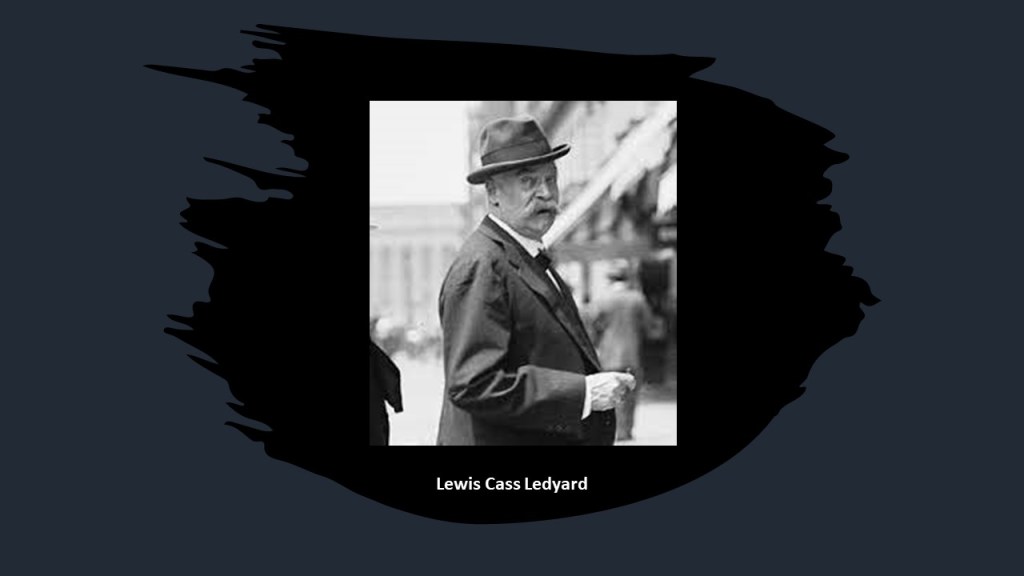

Descendents of Lewis Cass included great-grandson Augustus Cass Canfield, long-time President and Chairman of the Harper & Brothers Publishing Company (later known as Harper & Row)…

…and grandson Lewis Cass Ledyard, a New York City lawyer, personal counsel to financier J. P. Morgan, and a President of the New York Bar Association.

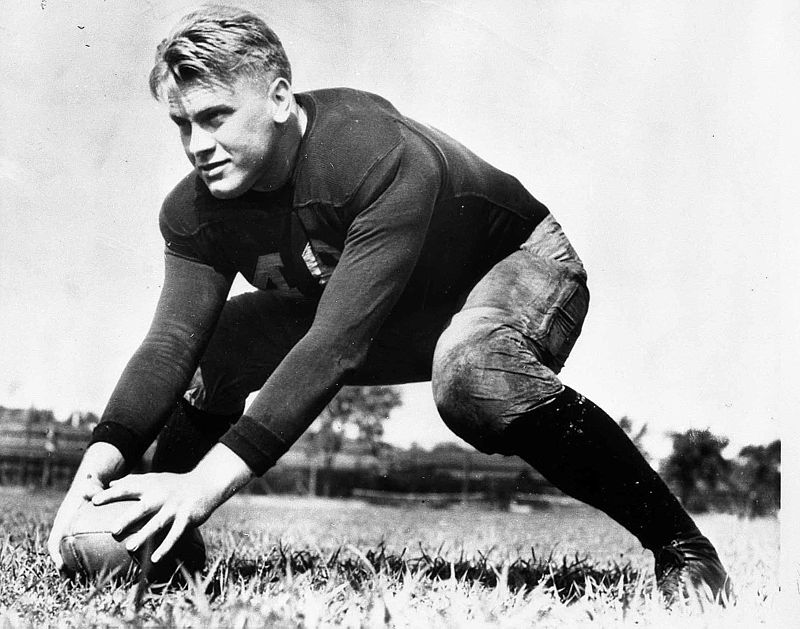

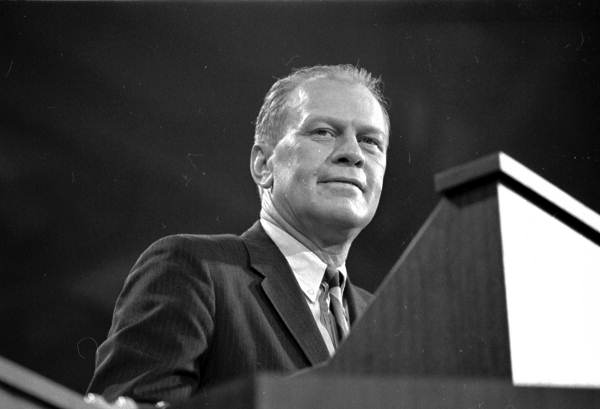

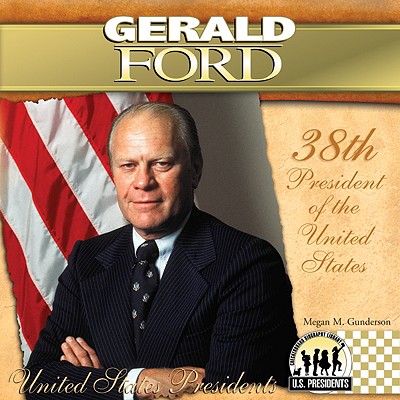

The other statue representing the State of Michigan is Gerald Ford, the only U. S. President from Michigan.

He was never elected to the office of President or Vice-President.

He was the leader of the Republicans in the House of Representatives when he was nominated to be President of the United States after the resignation of Richard Nixon in 1974.

He was defeated for a full-term by Jimmy Carter in 1976.

He was born Leslie Lynch King Jr in July of 1913 in Omaha, Nebraska, where his parents lived in the home of his paternal grandparents on Woolworth Avenue.

His mother separated from his father shortly after his birth due to domestic abuse.

His paternal grandfather, Charles Henry King, a prominent businessman and banker in Omaha, also founded several cities in Wyoming and Nebraska, building up related businesses, banks, and freight operations with the westward expansion of the railroad.

King’s wealth was estimated to have been up to $20 million, and he was known as the wealthiest man in Wyoming.

The future President’s mother moved in with her parents in Grand Rapids, Michigan, and two-and-a-half years later married Gerald Rudolff Ford, a salesman in a family-owned paint and varnish company.

Though not formally adopted, Gerald Ford’s name change was formalized in 1935.

He attended Grand Rapids High School, where he was captain of the football team.

He went on to become a star player for the University of Michigan football team.

After graduating from the University of Michigan in 1935 with a bachelor’s degree in Economics, Ford turned down several offers to play professional football to become a boxing coach and assistant football coach at Yale University, and applied to the law school there.

Initially Ford was denied admission to the Yale Law School because of his full-time coaching responsibilities, but was admitted in the spring of 1938.

At the same time he was attending the Yale Law School, he was became the head coach of Yale’s Junior Varsity football team and worked as a male model for a couple of modelling agencies.

Ford graduated from the Yale Law School in 1948, and was admitted to the Michigan Bar.

He opened his law practice in Grand Rapids Michigan in May of 1941, with his friend Philip W. Buchen, who later became White House Counsel during the Ford Administration.

Ford enlisted in the Navy after the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor on December 7th of 1941.

In April of 1942, he received a commission as a 2nd-Lieutenant in the U. S. Naval Reserve.

He was initially sent for instruction to the V-5 Flight Instructors School at the Naval Academy in Annapolis, Maryland, and then assigned to instruct at the Navy Preflight School in Chapel Hill, North Carolina, and coached all nine sports taht were offered there.

While in Chapel Hill, he was promoted to Lieutenant, and by the end of World War II, had attained the rank of Lieutenant Commander, and had served on-board the carrier USS Monterey in the Pacific Theater.

He was honorably discharged from the Navy in February of 1946.

Ford returned to Grand Rapids in 1946, and became active in Republican politics, successfully running for the U. S. Congress for the first time in 1948, and subsequently serving as a member of the U. S. Congress holding Michigan’s 5th Congressional District seat from 1949 to 1973.

His time in Congress was known for its modesty, and he saw himself as a negotiator and reconciler.

President Johnson appointed Gerald Ford to the Warren Commission, which was set-up on November 29th of 1963 to investigate the assassination of President Kennedy.

The Warren Commission concluded in its final report presented to President Johnson on September 24th of 1964 that President Kennedy was assassinated by Lee Harvey Oswald, and that Oswald acted alone.

Gerald Ford became the House Minority Leader in 1965, after the Democrat President Lyndon B. Johnson was elected President in 1964.

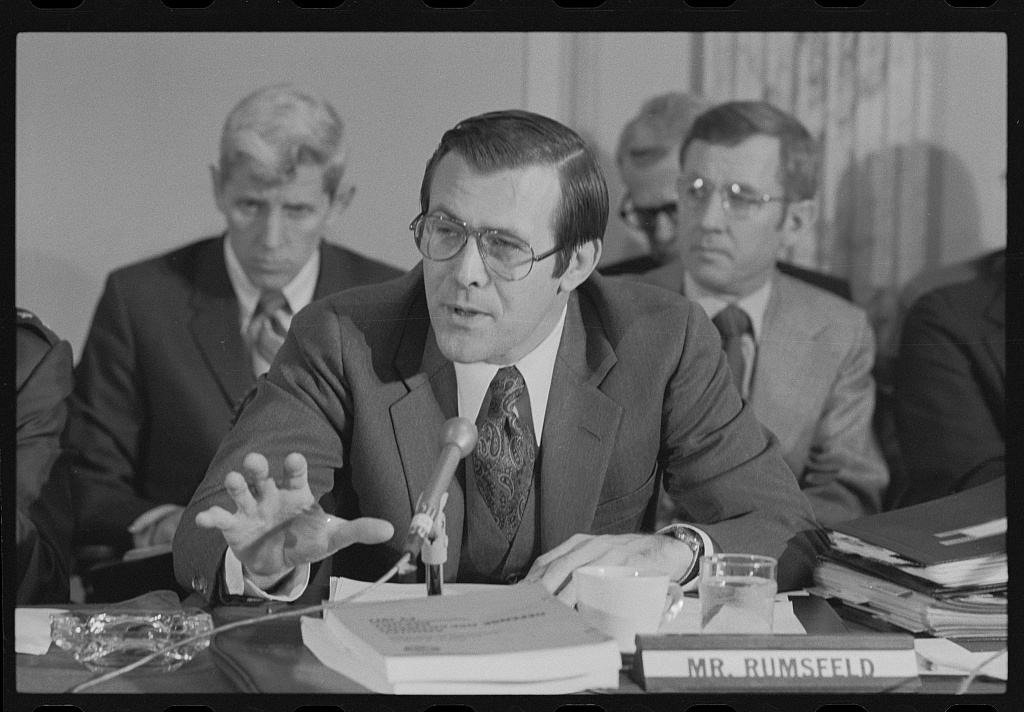

He was encouraged to run for the position by a Republican Caucus known as the “Young Turks,” which included Donald Rumsfeld, who was the Congressman from Illinois’ 13th Congressional District at the time.

Rumsfeld later became Secretary of Defense in both the Ford and George W. Bush Administrations.

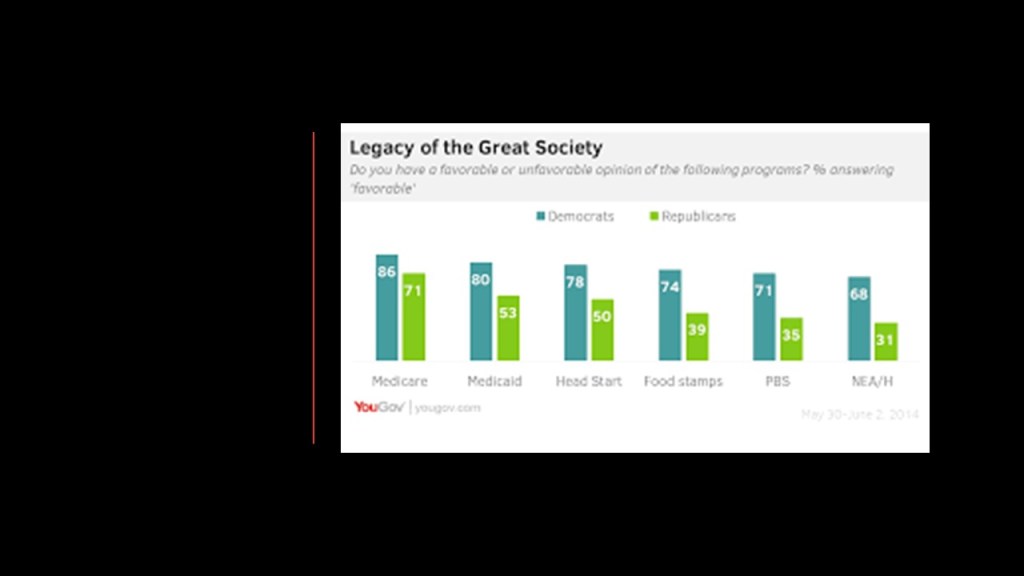

The Johnson Administration was able to pass a series of social programs in 1964 and 1965 known as the “Great Society” with a Democratic majority in the House and Senate.

These included programs that addressed things like education, medical care, urban problems, rural poverty, and transportation.

With criticism of the Johnson Administration’s handling of the Vietnam War growing, the mid-term elections in 1966 brought about a 47-seat swing to the Republicans in Congress.

This was not enough to give Republicans the majority, but it did give Ford at the Minority Leader the opportunity to prevent the passage of further Great Society programs, and Ford was openly critical of the Vietnam War.

Ford was nominated, and became Vice-President in 1973 after his nomination passed the House and Senate, after the sitting Vice-President, Spiro Agnew, resigned after pleading no-contest to a count of tax evasion stemming from his time as Governor of Maryland.

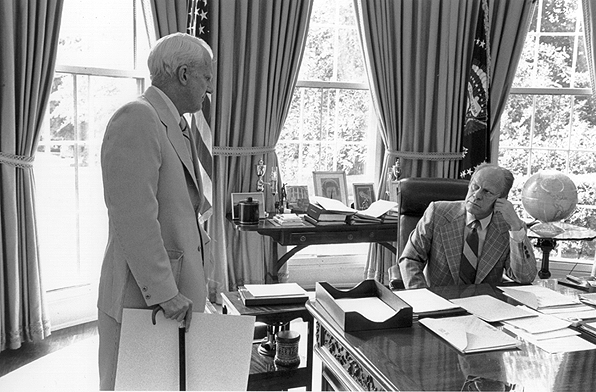

The Watergate Scandal was unfolding as Ford became Richard Nixon’s Vice-President, and after Nixon’s resignation from the Office of President on August 9th of 1974, Gerald Ford automatically became the 38th President of the United States.

And President Gerald Ford nominated Nelson Rockefeller, John D. Rockefeller’s grandson, to be his Vice-President, and Rockefeller’s nomination passed the House and the Senate.

President Ford issued Proclamation 4311 on September 8th of 1974, in which he fully and unconditionally pardoned Richard Nixon for any crimes he might have committed while President of the United States.

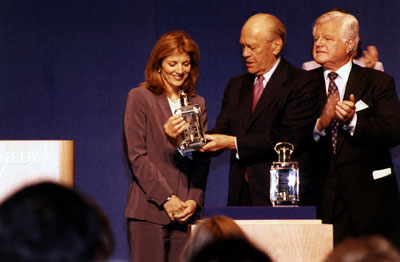

While many believe Ford lost the 1976 Presidential Election because of the controversial pardon, in 2001, Gerald Ford received the John F. Kennedy Profile in Courage Award from the John F. Kennedy Library Foundation for his pardon of Nixon.

Ford inherited Nixon’s Cabinet when he first took office.

He replaced all of Nixon’s cabinet members except for Secretary of State, Henry Kissinger and Secretary of the Treasury, William E. Simon.

Ford selected George H. W. Bush as the Chief of the U. S. Liaison Office to the People’s Republic of China in 1974 and then Director of the CIA in late 1975.

Ford’s first Chief of Staff was Donald Rumsfeld, and Dick Cheney became Ford’s Chief of Staff after Rumsfeld became the youngest Secretary of Defense in 1975.

During the years of Gerald Ford’s Presidency between August 9th of 1974 and January 20th of 1977, here are some of the things that happened:

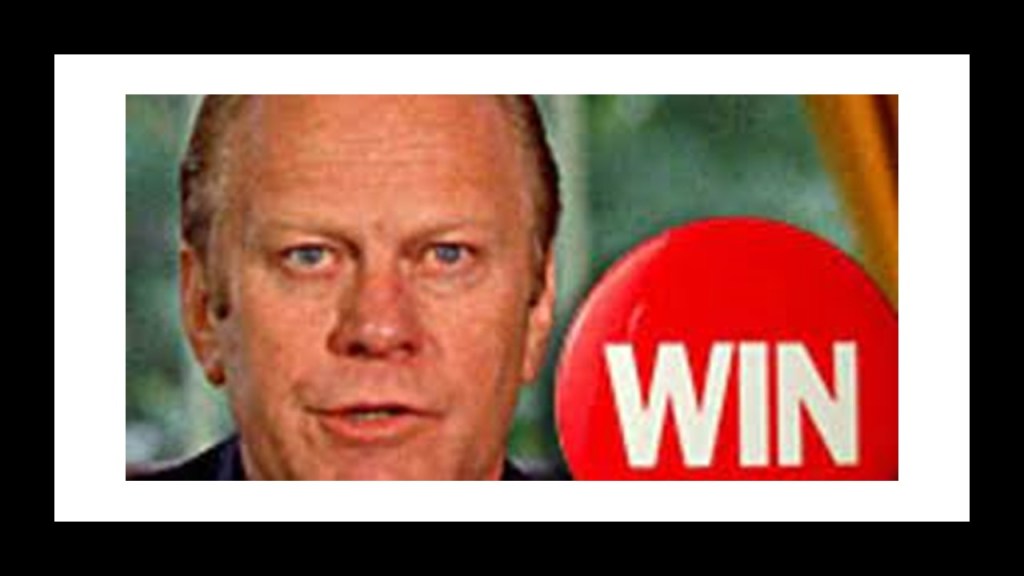

The Economic Policy Board was created by Executive Order on September 30th of 1974 in response to concern about the economy and rising inflation.

The Economic Policy Board was created to oversee the formulation, coordination and implementation of all economic policies to combat rising grocery prices, eroding purchasing power, rising cost of doing business and unemployment.

A month later, in October of 1974, President Ford went to the American public with his WIN, or Whip Inflation Now, Program, encouraging people to wear WIN buttons, and to curb their spending and consumption.

Controlling public spending was seen as a way to rein in inflation.

It is interesting to note that the U. S. sank into the worst recession since the Great Depression during this time, and unemployment had reached 9% by May of 1975.

Special Education was established in the United States when Ford signed the “Education for All Handicapped Children Act” in 1975.

In November of 1975, President Ford attended the first meeting of the Group of Seven Industrialized Nations, also known as G7, where he secured membership for Canada.

Also in November of 1975, Ford adopted the global human population control recommendations of National Security Study Memorandum 200, also known as the Kissinger Report, a National Security Directive completed on December 10th of 1974 by the United States Security Council under the direction of Henry Kissinger, on the initial order of President Nixon.

The Memorandum and policies developed from it were seen as a way the U. S. could use population control to: 1) Limit the political power of undeveloped nations; 2) ensure the easy extraction of foreign natural resources; 3) prevent young anti-establishment individuals from being born; and 4) protect American businesses from interference from nations seeking to support their growing populations.

President Ford had announced the end of the Vietnam War for the United States in a speech he gave at Tulane University on April 23rd of 1975, after Congress voted against his request for a $722 million aid package for South Vietnam, though money was given for evacuation.

The Fall of Saigon took place on April 30th of 1975, with entry of North Vietnamese forces into the city, and right after the helicopters of Operation Frequent Wind evacuated Americans, at-risk South Vietnamese and third-country nationals from the capital of South Vietnam.

Swine Flu showed up in February of 1976, when an Army recruit at Fort Dix mysteriously died, and four other soldiers were hospitalized.

Soon after, Public Health officials in the Ford Administration urged that every person in the United States be vaccinated for swine flu, but the program was cancelled in December of 1976 after approximately 25% of the population had been vaccinated.

After Ford lost the 1976 Presidential Election to Jimmy Carter, he stayed active in public life in a variety of ways.

He died on December 26th of 2006 at home in Rancho Mirage, California, from end-stage Coronary Artery Disease.

After lying in-state in the Rotunda on December 30th of 2006, and a funeral for him held at the National Cathedral in Washington, DC, he was interred at his Presidential Museum in Grand Rapids, Michigan.

Hmmm.

The unelected President Gerald Ford was known for his unassuming and conciliatory manner.

But could “Unassuming Jerry” have been selected for the Presidency with another agenda hidden from view, while the Nation and the World was distracted with the Watergate Scandal and Hearings?

Did in fact the short-lived Ford Administration bring together the major players of the New World Order under the auspices of the U. S. Presidency in order to solidify and advance the New World Order Agenda for its future progression?

I did a Freemason search on President Ford, and sure enough, it came back positive.

Not only was he a 33rd-Degree Freemason in the Scottish Rite, while he was in the Oval Office, he received the degrees of York Rite Freemasonry

The highest order of the York Rite is the Knights Templar.

I couldn’t confirm that Ford was a Knight Templar, but I did find him in their February 2003 magazine.

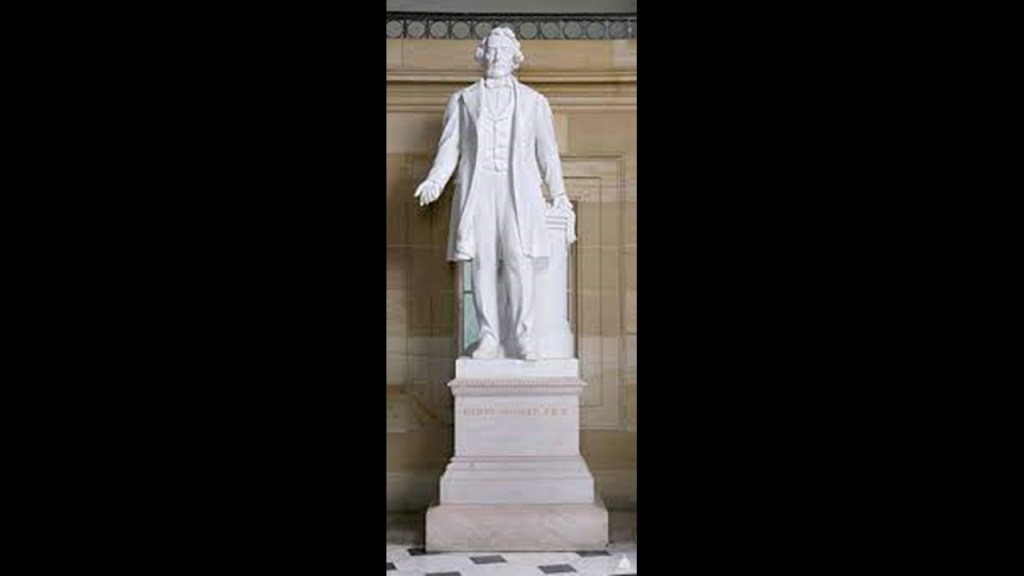

The State of Minnesota is represented by Henry Mower Rice and Maria Sanford in the National Statuary Hall.

Henry Mower Rice was a fur trader and prominent Minnesota politician involved in Minnesota becoming a state.

Henry Mower Rice was born in Waitsfield, Vermont, on November 29th of 1816, to parents of English ancestry in New England since the 1600s.

His father died when he was young, so he lived with family friends when growing up.

The town of Waitsfield was established by charter in February of 1782, and granted to Revolutionary War Militia Generals Benjamin Wait, Roger Enos, and others.

Rice moved to Detroit, Michigan, when he was 18, and he participated in surveying the canal route around the rapids of Sault Ste. Marie between Lake Superior and Lake Huron.

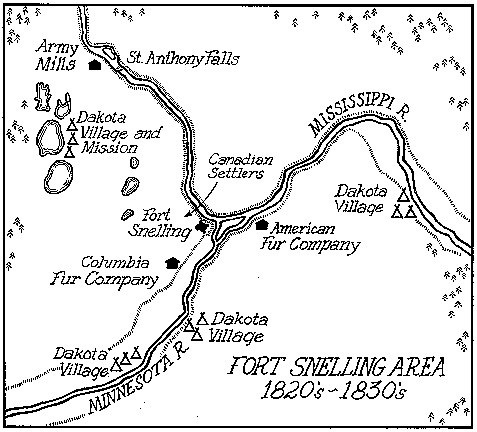

Then in 1839, Rice got a job at Fort Snelling, near Minneapolis, Minnesota, and became a fur trader with the Ojibwe and Winnebago people in the area.

Rice attained a position of trust and influence with them, and he was instrumental in negotiating the 1847 Treaty of Fond du Lac with the Ojibwe, in which they ceded extensive lands to the United States.

Historic Fort Snelling was said to have been constructed in the 1820s.

The Fort served as the main center for U. S. Government forces during the Dakota War of 1862, also known as the Sioux Uprising, an armed conflict between the United States and several tribes of the Eastern Dakota known as the Santee Sioux.

Today what is called the Unorganized Territory of Fort Snelling includes not only the historic fort, but the Coldwater Spring Park, Minneapolis-Saint Paul International Airport, parts of the Mississippi National River and Recreation Area, a National Guard base, a National Cemetery, the Minneapolis VA Medical Center, and several other state government facilities as well.

Rice lobbied for the bill to establish the Minnesota Territory in 1849, and went on to serve as its delegate in the U. S. Congress between March 4th of 1853 and March 4th of 1857.

He facilitated Minnesota becoming a state in 1858 by his work on the Minnesota Enabling Act, which passed Congress in February of 1857.

When Minnesota became a state, Henry Mower Rice and James Shields were elected by the Minnesota Legislature as Democrats to the United States Senate, and Rice served in this capacity from May 11th of 1858 to March 4th of 1863.

The other Minnesota Senator who served with Henry Mower Rice as the State of Minnesota’s first U. S. Senators, James Shields, represents the State of Illinois in the National Statuary Hall.

He was an Irish-American Democratic politician and U. S. Army officer, and the only person in U. S. history to serve as Senator for three different states, and one of only two to represent more than one state.

He represented Illinois from 1849 to 1855; Minnesota from 1858 to 1859; and Missouri in 1879.

In addition to the 1847 Treaty of Fond du Lac with the Ojibwe, Henry Mower Rice was involved in a number of treaties, including the 1846 Winnebago Treaty ratified in Washington, DC.

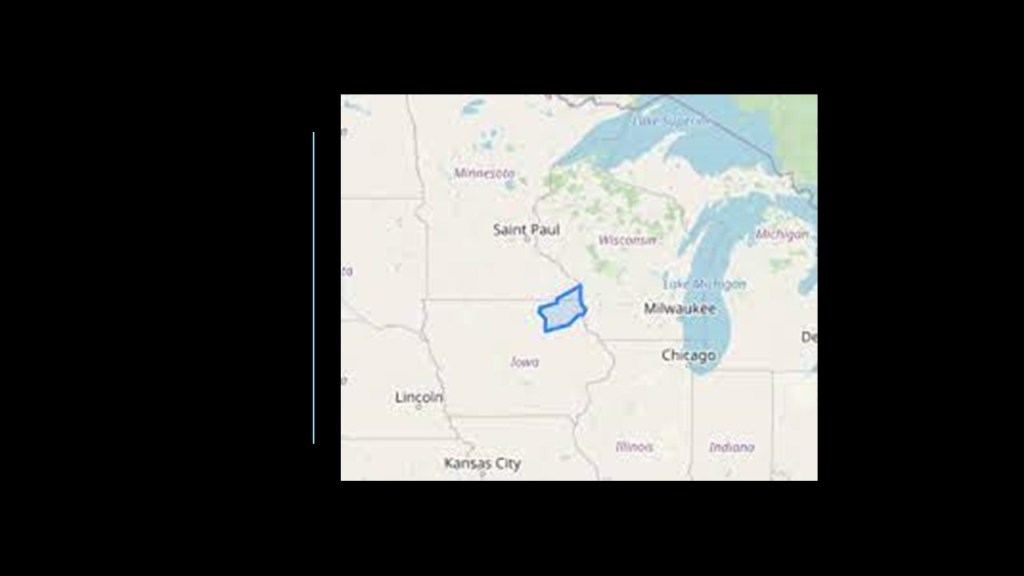

Originally native to Wisconsin, the Winnebago had been moved to a reservation in northeastern Iowa as a result of Treaties signed in 1832 and 1837 to a reservation in northeastern Iowa called “neutral ground,” an area considered to be a buffer between other native americans.

The Winnebago were unhappy with American settlers who were encroaching on their reservation land in Iowa, and asked to be moved, hence the 1846 Treaty.

So in exchange for their reservation land in the Iowa Territory for land in the Minnesota Territory, they were offered researvation land in Long Prairie, Minnesota.

Long story short, the Winnebago were shuffled around a lot, and Henry Mower Rice was involved in this whole process, both as a negotiator and in 1850 received a contract from the federal government to remove any Winnebago who had not moved to their reservation land in Long Prairie, Minnesota, in which he was paid per person to bring the unaccounted for Winnebago people to the reservation.

Rice was also involved in the 1854 Treaty of LaPointe, Wisconsin, where the Lake Superior Ojibwe ceded all of their land in the Arrowhead Region of northeastern Minnesota in exchange for reservations in Michigan and Minnesota.

All that is said of Henry Mower Rice’s death is that he died in 1894 during a visit to San Antonio, Texas, and was buried in the Oakland Cemetery in St. Paul, Minnesota.

Maria Sanford is the other statue representing Minnesota in the National Statuary Hall.

Maria Sanford was an American educator, and one of the first female professors in the United States.

Maria Sanford was born in Saybrook, Connecticut, in December of 1836.

Old Saybrook is located where the Connecticut River meets Long Island Sound.

She received her education from the New Britain Normal School, the first training school for teachers in Connecticut, and the sixth in the United States.

Today it is Central Connecticut State University.

After graduating from the New Britain Normal School with honors in 1855, she taught in various schools around Connecticut for the next twelve years.

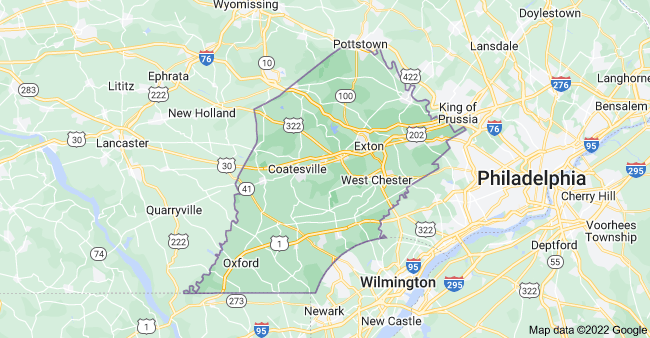

She moved to Pennsylvania in 1867, and became a principal and superintendent of schools in Chester County.

Known as an innovator, she conducted regular meetings of teachers and demonstrated new teaching methods.

She became a Professor of History and English at Swarthmore College in Pennsylvania from 1871 to 1880.

Swarthmore College was founded by Quakers in 1864, which would have been one year before the end of the American Civil War, and the first classes offered in 1869.

Sanford was invited to become a Professor at the University of Minnesota by its President, Dr. William Watts Folwell, and she joined the faculty there in 1880 as a Professor of Rhetoric and Elocution, where she also lectured in literature and art history, a position she held until her retirement in 1909.

She was a leading voice outside of academia.

Among other things, she was an advocate for the conservation and beautification of Minnesota for the cause of the Chippewa National Forest from within the Minnesota Federation of Women’s Clubs, along with fellow clubwoman and forest conservationist Florence Bramhall…

Sanford reached out to her community and to the nation with the power of her speeches, travelling throughout the United States delivering more than 1,000 patriotic speeches.

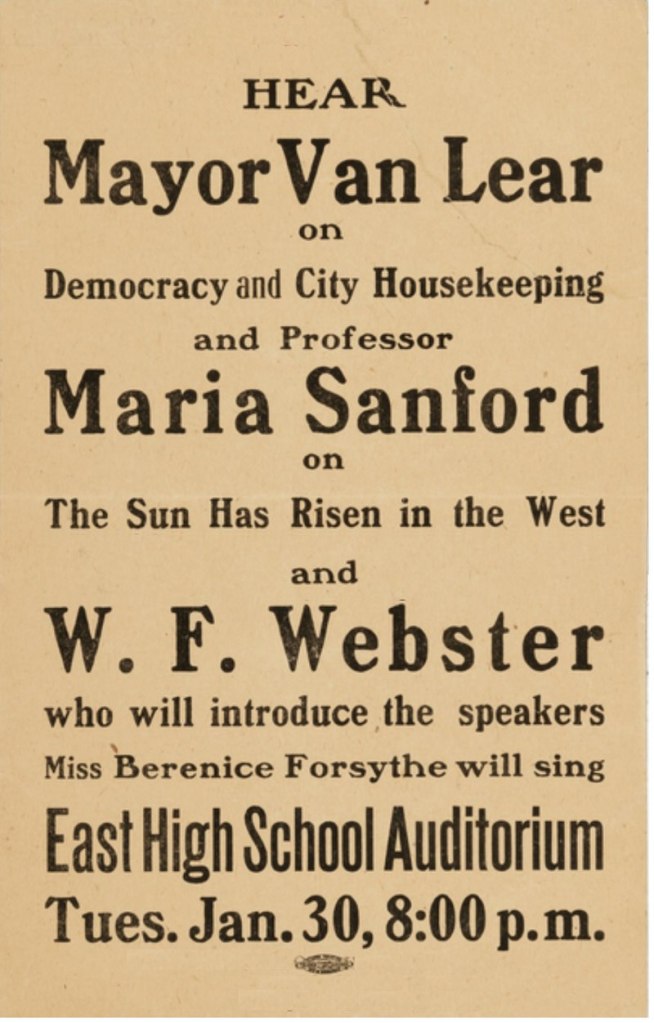

In 1917, she delivered a speech, along with the Mayor of Minneapolis at the time Thomas Van Lear, on good government and women’s suffrage.

She delivered her most famous speech to the Daughters of the American Revolution Convention in April of 1920, entitled “An Apostrophe to the Flag.”

But not only did she give speeches, she took on a highly active role in the public sector, including, but not limited to, becoming the head director of Northwestern Hospital and serving as president of the Minneapolis Improvement League.

The University of Minnesota was said to have constructed Sanford Hall as a women’s dormitory in 1910 in honor of Maria Sanford.

Maria Sanford died on April 21st of 1920 in Washington, DC, and was buried in Philadelphia’s Mount Vernon Cemetery.

We are told that for months after Sanford’s death, she was so beloved in Minnesota that gatherings in her memory were held at the University of Minnesota and her home church Como Congregational.

Jefferson Davis and James Z. George represent the State of Mississippi in the National Statuary Hall.

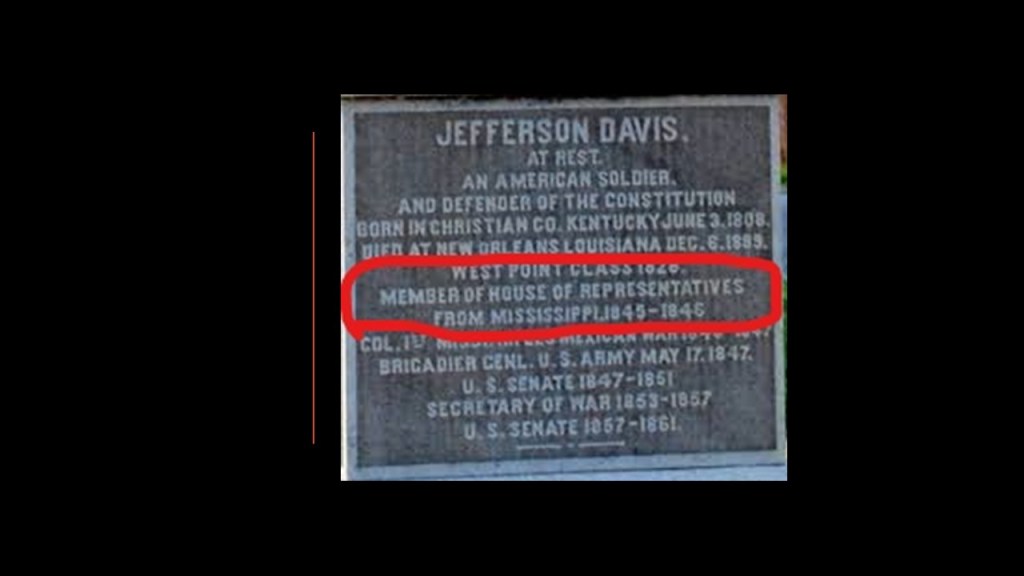

Jefferson Davis represented Mississippi as a Democrat in the United States Senate and House of Representatives before the American Civil War, and he was President of the Confederate States during the Civil War, between 1861 and 1865.

He had served as Secretary of War from 1853 to 1857 during the Administration of President Franklin Pierce.

Jefferson Davis was born in Fairview, Kentucky, on the family homestead in June of 1808, and was the youngest of ten children. He was named after the President at the time, Thomas Jefferson.

The Jefferson Davis State Historic Site is a Kentucky State Park that commemorates his birthplace.

It is very interesting to note that a 351-foot, or 107-meter, – tall obelisk commemorating Davis is located there.

This obelisk is the fourth-tallest monument in the United States; the tallest, unreinforced concrete structure in the world, and the world’s tallest concrete obelisk.

We are told the idea of a monument for Davis was said to have been proposed by former Confederate General Simon Bolivar Buckner, Sr, at a reunion in 1907 of the First Kentucky Brigade, also known to history as the “Orphan Brigade.”

Its nickname of “Orphan Brigade” was said to have come from one of its Commander, General Hanson Breckinridge, riding among the survivors after the 1862 Battle of Stones River in Middle Tennessee, where the Brigade suffered heavy casualties, saying repeatedly, “My poor orphans! My poor orphans!”

The Brigade saw fighting during the entirety of the American Civil War, including being Confederate combatants against the Union Army General Sherman’s March to the Sea, which took place from Sherman’s capture of Atlanta in November 15th of 1864 to his capture of Savannah, Georgia, on December 21st of 1864.

General Sherman’s forces followed a scorched earth policy of destroying not only military targets, but also industry, infrastructure, and civilian property.

Well, well, well…what do we have here?

It sure looks like General Sherman was a Freemason!

The construction of the massive obelisk monument to Davis was said to have started in 1917 and completed in 1924.

Jefferson’s father, Samuel Davis, served in the American Revolutionary War, and received a land grant near Washington, Georgia, for his service.

Interesting to note that Washington, Georgia, is where the Confederacy voted to dissolve itself, bringing the American Civil War to an end. More on this later.

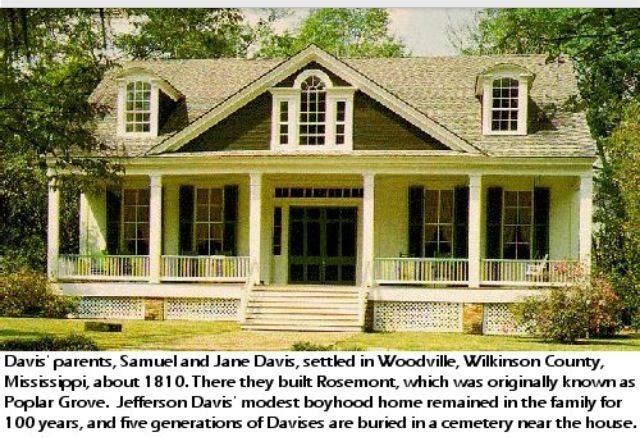

The family moved from the family homestead in Georgia when Jefferson was two-years-old, ending up near Woodville, Mississippi, where his father operated a small cotton plantation called Rosemont, and was President Davis’ family home until 1895.

In 1816, when Davis was 8-years-old, his father sent him to a Catholic Preparatory School in Springfield, Kentucky run by the Dominicans called Saint Thomas College.

Today called the St. Rose Priory Church, this religious house was first founded by Dominican friars as a college around 1808, and was the first Catholic educational institution west of the Allegheny Mountains.

Davis returned to Mississippi in 1818, where he studied first at Jefferson College in Washington, Mississippi…

…and then after attending the Wilkinson Academy near Woodville, Mississippi for 5 years, he attended Transylvania University in Lexington, Kentucky, starting in 1823.

His father Samuel died while he was here, who had already sold the Rosemont Plantation to his eldest son Joseph because of debt.

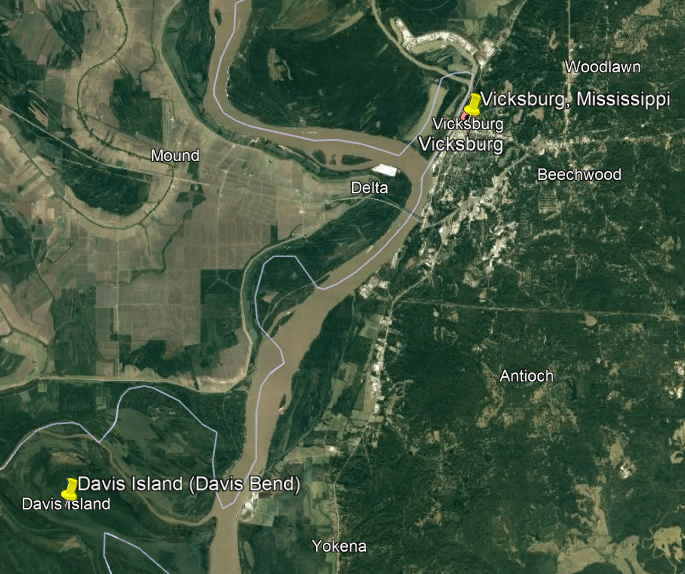

Joseph E. Davis already owned land on the Mississippi River in what became known as Davis Bend, Mississippi, and is now called Davis Island.

Joseph had established the Hurricane Plantation there between 1824 and 1827 as a “model cooperative slave community” after studying utopian socialist ideas of Robert Owen, a Welsh textile manufacturer, philanthropist and social reformer, with Joseph’s stated goal being the achievement of a higher-functioning and profitable slave community by provision of decent care and opportunties for self-governance.

More on the Davis Bend Plantations of Joseph and Jefferson Davis shortly.

Davis Bend, known today as Davis Island, is 50-miles, or 81-kilometers south of Vicksburg on the Mississippi River.

Joseph E. Davis was 23-years older than Jefferson, and took on being the role of a surrogate father to him after their father Samuel’s death.

In 1824, Joseph secured an appointment for Jefferson at the United States Military Academy in West Point, New York.

Jefferson Davis was continually getting into disciplinary trouble there for drunk and disorderly conduct while he was there, but managed to graduate 23rd in a class of 33.

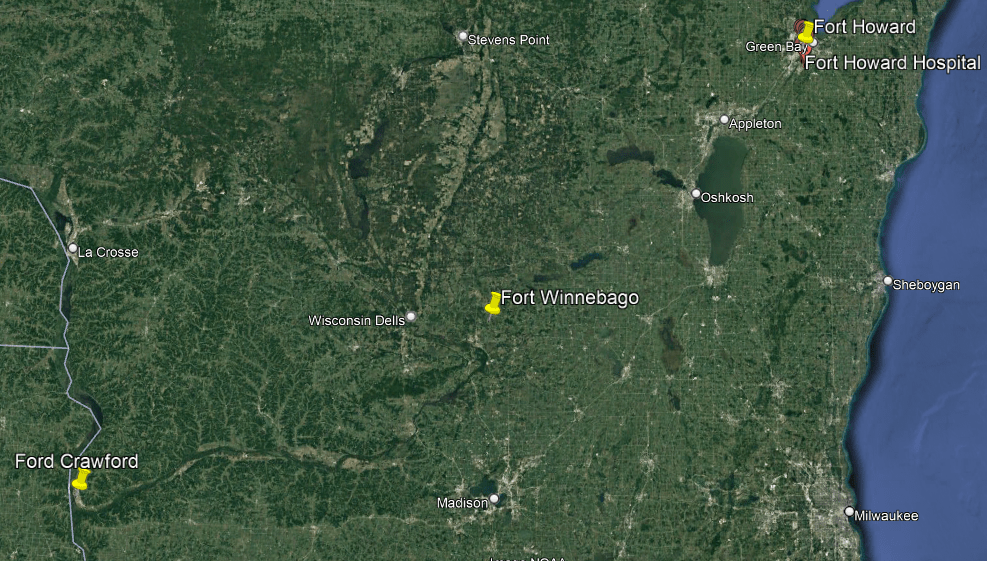

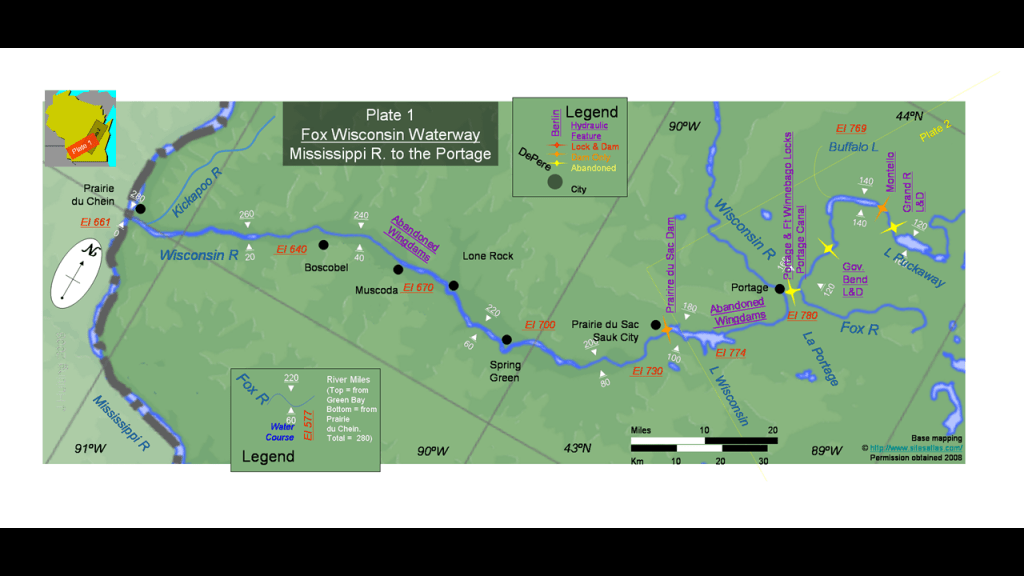

The newly-commissioned Second-Lieutenant Jefferson was assigned to the 1st Infantry Regiment, and his duty stations were at Fort Crawford in Prairie du Chien, Wisconsin, and Fort Winnebago, the middle of three fortifications along the Fox-Wisconsin Waterway that included Fort Crawford and Fort Howard in Green Bay, Wisconsin.

Forts Crawford and Howard were said to have been built during the War of 1812 to protect the important trade route of the Fox-Wisconsin Waterway between Lake Michigan and the Mississippi River from British invasion.

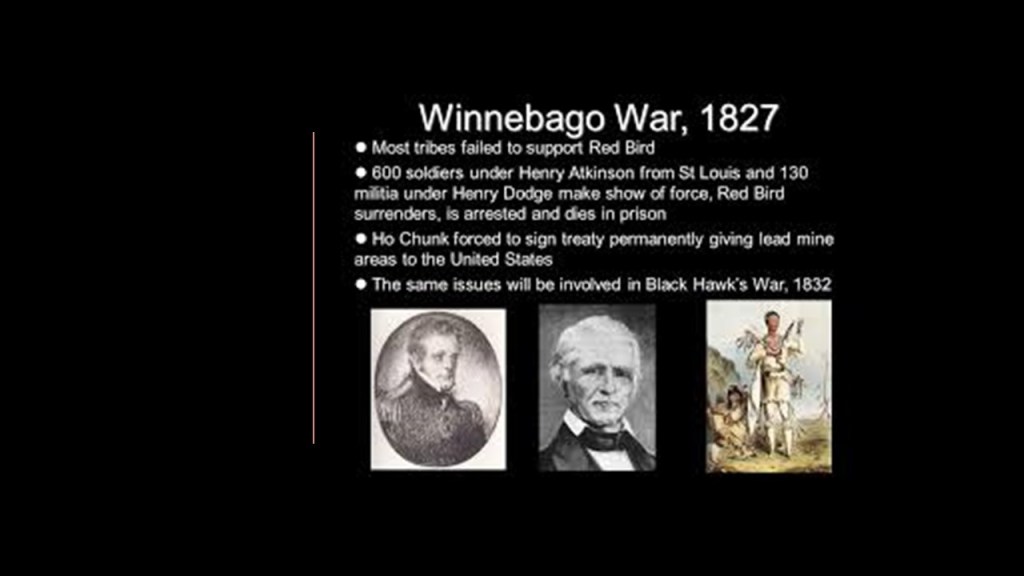

Fort Winnebago was said to have been built in 1828 in an effort to keep peace between white settlers and the regions Native American tribes following the 1827 Winnebago War, which ended quickly after a portion of the Winnebago had risen up in reaction to a wave of lead miners trespassing on their land.

As a result of the war, the Winnebago, also known as the Ho-Chunk, were compelled to cede the lead mining region to the United States.

It is interesting to note that the Fox-Wisconsin Waterway is a lock, dam and canal system that was said to have been built in the mid-19th-century, and used for transportation until the coming of the railroad made it obsolete.

We are told use of the waterway was never substantial, and it slowly died out, and the lock system on the Lower Fox River between Lake Winnebago and Green Bay was closed in 1983 to prevent the upstream spread of invasive species like lamprey.

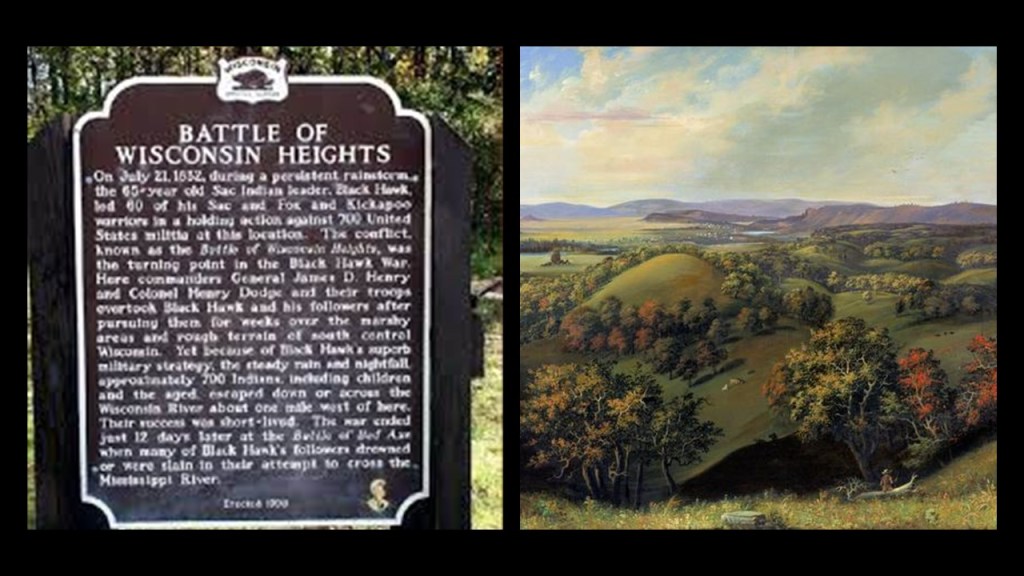

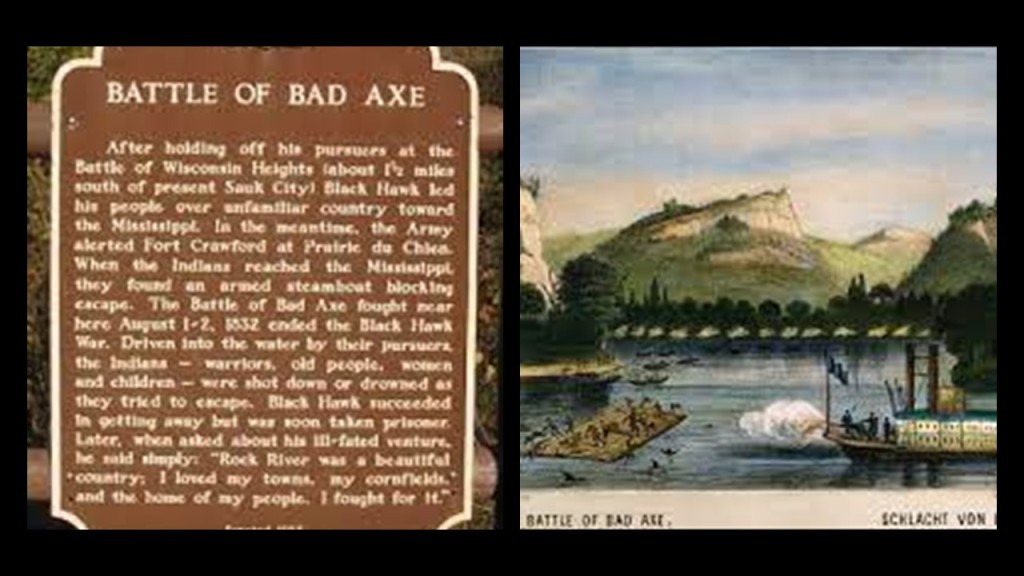

Jefferson Davis was ill with pneumonia during the Black Hawk War in March of 1832, in which the Sauk leader Black Hawk and a group of Sauk, Fox, and Kickapoo were attempting to reclaim land sold to the United States in the disputed 1804 Treaty of St. Louis.

They were defeated at the Battle of Wisconsin Heights on July 21st of 1832…

…and the Battle of Bad Axe near present-day Victory, Wisconsin, on August 1st and 2nd of 1832, which has been called a massacre since the 1850s.

Black Hawk was soon taken prisoner, and the end of the Black Hawk War opened up much of Illinois and Wisconsin for further settlement.

It also gave impetus to the United States policy of Indian Removal, where Native American tribes were pressured to sell their lands and move to reservations west of the Mississippi River.

Though absent on furlough for the Black Hawk War, Jefferson Davis was said to have had the duty of escorting Black Hawk for detention at the Jefferson Barracks near St. Louis.

Davis returned to Ft. Crawford in January of 1833, from which he was reassigned by his commanding officer Colonel and future U. S. President Zachary Taylor that spring after Davis wanted to marry Taylor’s daughter, and Taylor said no.

He was assigned to the United States Regiment of Dragoons, which was formed by an Act of Congress on March 2nd of 1833 to patrol the frontier as a result of the Black Hawk War.

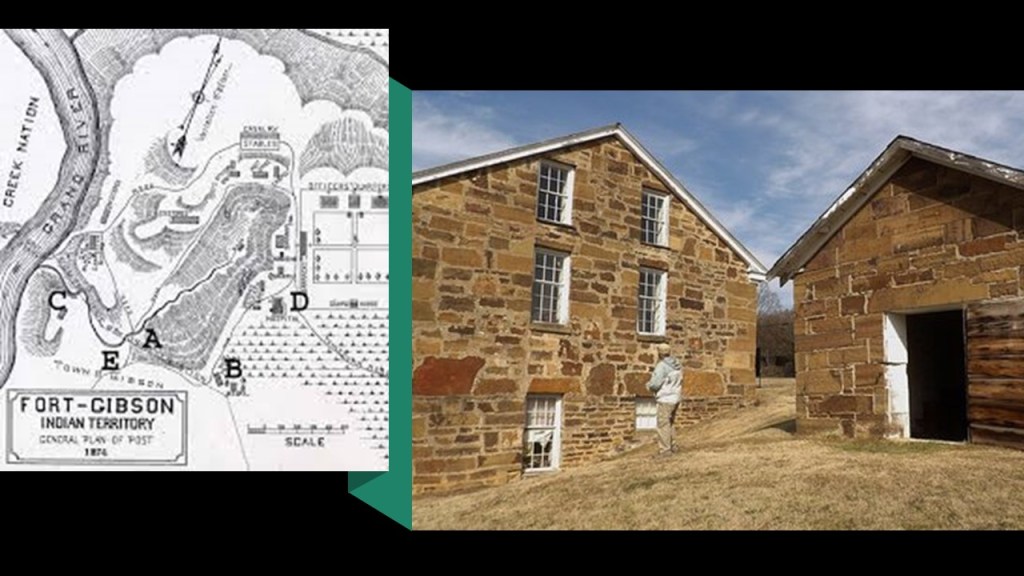

He was promoted to First Lieutenant, and assigned to Fort Gibson in the Arkansas Territory, the furthest west military post at the time in the United States.

It was here that Davis was court-martialed in February of 1835 for insubordination.

Though acquitted, he requested a furlough, and resigned from the U. S. Army at the age of 26 in June of 1835.

Upon returning to Mississippi after Davis resigned from the Army, he decided to become a planter.

His brother Joseph provided him with 800 acres, or 320 hectares of land at Davis Bend, and he started cultivating cotton at what became known as Brierfield Plantation.

Davis had kept in touch with Sarah Taylor, Zachary Taylor’s daughter, and he finally gave his consent to their marriage.

They were married at Beechland, a home said to have been built in 1812, near Jeffersontown, Kentucky, in June of 1835.

In August of 1835, the newlyweds travelled to the Locust Grove Plantation of his sister Anna Smith in West Feliciana Parish, Louisiana, where they both contracted severe cases of malaria.

Sarah subsequently died on September 15th of 1835 at the age of 21, and was buried at the Locust Grove Cemetery.

Jefferson Davis gradually improved.

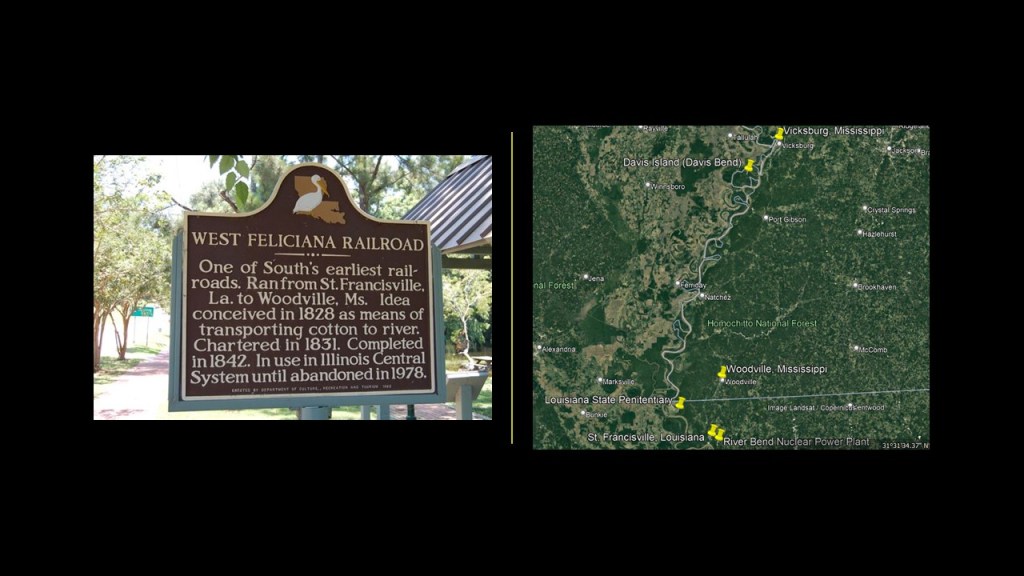

Interesting to note the presence of the River Bend Nuclear Power Plant and Louisiana State Penitentiary in West Feliciana Parish.

The Louisiana State Penitentiary, also known as Angola and the Alcatraz of the South, it is the largest maximum-security prison in the United States.

Also, one of the south’s earliest railroads ran from St. Francisville, the Parish Seat, to Woodville, Mississippi, where the Davis Family Homestead Rosemont was located.

All these findings pique my interest, and I wonder if this area was a power node of some sort on the Earth’s original energy grid system.

In the years following Sarah’s death, Jefferson developed the Brierfield Plantation and with the help of his brother, Joseph, became increasingly involved in politics, with their particular concern about national efforts to limit slavery in new territories.

His political career started in 1840, when he attended a Democratic Party meeting in Vicksburg, and served as a delegate to the state party convention in Jackson, and he served again as a delegate in 1842.

He lost the election for the State House of Representatives for Warren County in November of 1843.

In 1844, he was chosen to be a convention delegate again, and he was selected as one of Mississippi’s six Presidential electors for the 1844 Presidential Election.

At the same time this was happening, he met 18-year-old Varina Banks Howell, the daughter of New Jersey Governor Richard Howell, to whom he delivered the invitation from his brother Joseph to stay at the Hurricane Plantation for the Christmas Season.

They were married in February of 1845.

Davis ran for election to the U. S. House of Representatives in 1845, and won the election.

He was a strong advocate, among other things for States’ rights, political powers which are held for state governments rather than the federal government.

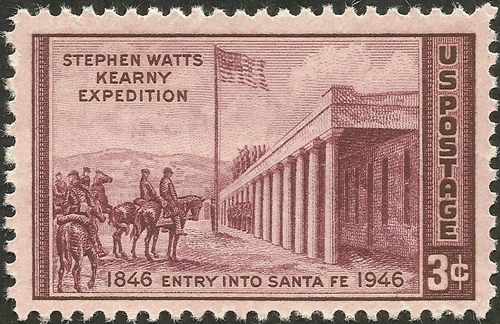

The Mexican-American War started on April 25th of 1846 during Davis’ Congressional term.

The State of Mississippi raised the First Mississippi Regiment, a volunteer unit, for the U. S. Army, and Davis was interested in joining it if he could be its commanding officer.

He was ultimately elected as its colonel, and while not resigning his seat in the House, he left a resignation letter with his brother to be used at the appropriate time.

Davis was able to get new percussion rifles for his unit as a favor returned by President James Polk for Davis’ support of Polk’s Walker Tariff, a decision which was not supported by the Commanding General of the U. S. forces, Winfield Scott because the new rifle had not been sufficiently tested.

The percussion rifle became known to history as the “Mississippi Rifle,” and his unit as the “Mississippi Rifles.”

Davis distinguished himself during the Mexican-American War during the Battle of Monterrey, where he led a charge that took the Fort Teneria.

Davis took a leave of two-months to return to Mississippi, and learned that his brother Joseph had submitted his letter of resignation from Congress.

He returned to the Mexican-American War, and fought in the Battle of Buena Vista, which took place in February of 1847.

While his tactics stopped a flanking attack by Mexican forces before they could collapse the American line, he was wounded in the heel.

Upon his return to the States, Davis declined a federal commission as a Brigadier General from President Polk, but accepted an appointment by Mississippi Governor Albert G. Brown to fill a vacancy in the U. S. Senate.

Davis took his seat in the Senate in December of 1847, and he established himself right away as an advocate of the South and its expansion into the territories of the West.

Davis was against the Wilmot Proviso, which was an 1846 proposal in the U. S. Congress to ban slavery in territory acquired from Mexico as a result of the Mexican-American War.

He asserted that only states had sovereignty and not territories, arguing that territories were the common property of the United States and that Americans who owned slaves had a right to move into territories with their slaves.

The conflict over the Wilmot Proviso was one of the major events leading to the American Civil War.

Davis was reelected to the Senate in 1849, where he became the spokesman for the South.

He was opposed to the Compromise of 1850, which was a package of five separate bills passed by Congress which defused a political confrontation between slave and free states on the status of territories acquired in the Mexican-American War.

The compromise was designed by Whig Senator Henry Clay and Democratic Senator Stephen Douglas, with the support of President Millard Fillmore, who had taken office with the sudden death of President Zachary Taylor from an unknown digestive ailment in July of 1850 after serving only 16-months in office.

Jefferson Davis, who opposed the Compromise of 1850, resigned from his Senate seat in the fall of 1851 to run for Mississippi Governor on a States’ Rights platform.

He lost the election and though he no longer held political office, he turned down the reappointment to his Senate seat by the outgoing Governor.

He remained politically active by attending the 1852 Democratic Convention and campaigning that year for both Franklin Pierce and William R. King, with Franklin Pierce becoming the 14th President of the United States.

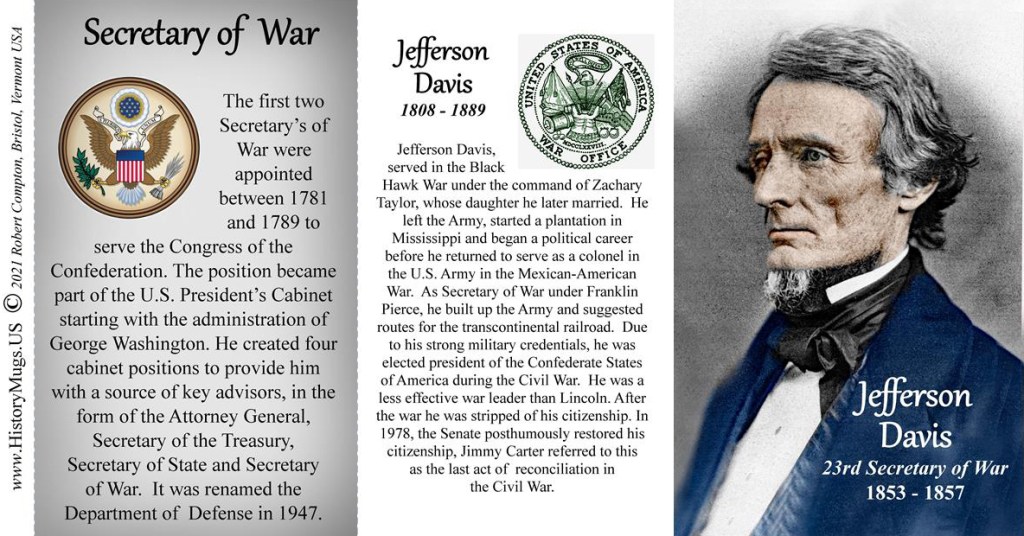

Jefferson Davis became Secretary of War in the Pierce Administration in March of 1853.

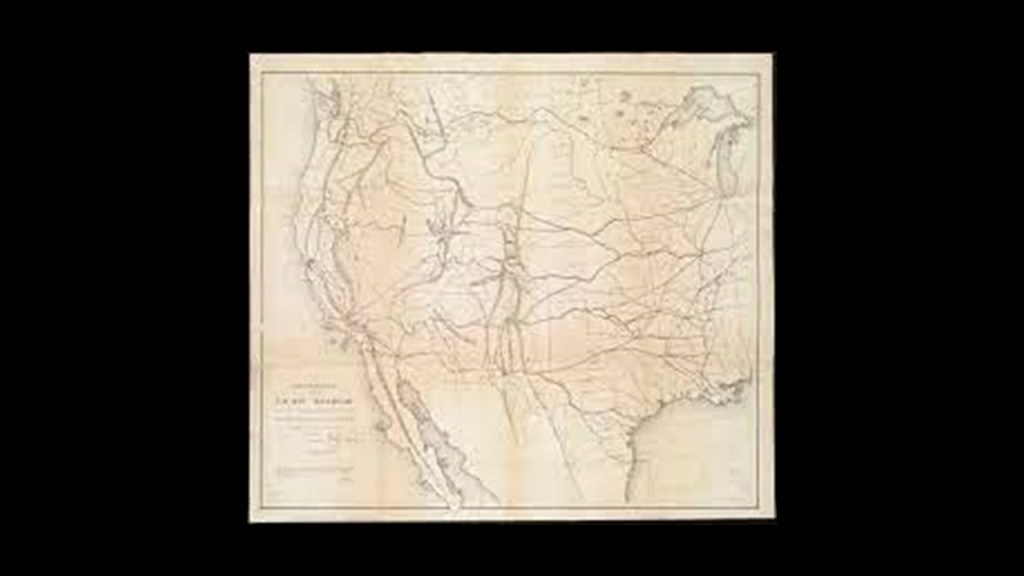

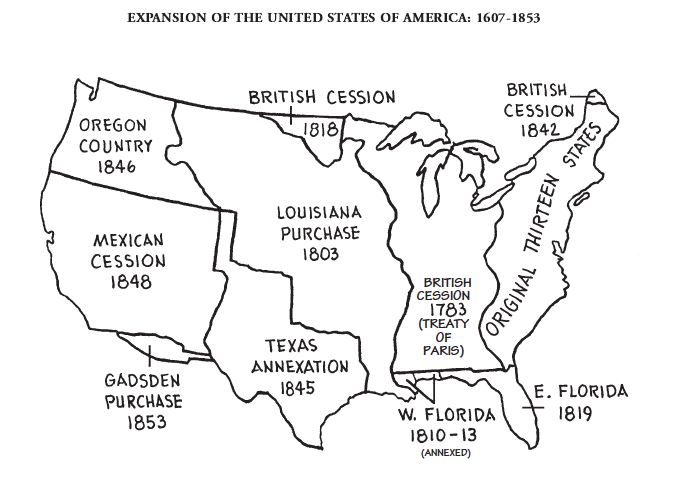

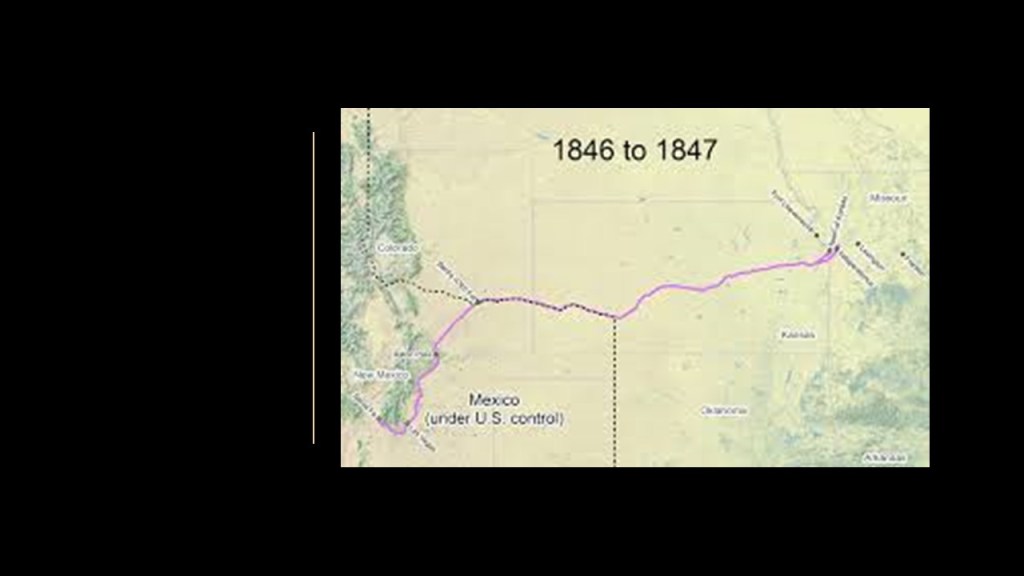

We are told that as Secretary of War, Davis advocated for a transcontinental railroad was needed for national defense, and he was given the task of overseeing the Pacific Railroad Surveys to determine the best of four possible routes after the U. S. Congress appropriated $150,000 on March 3rd of 1853, and authorized Davis to find the most practical and economical route for a railroad from the Mississippi River to the Pacific Ocean.

The Pacific Railroad Surveys, a series of explorations of the American West between 1853 and 1857 with the stated purpose of finding and documenting possible routes for a transcontinental railroad across North America.

There were five surveys conducted: the Northern Pacific Survey between the 47th-parallel north and the 49th-parallel north from St. Paul, Minnesota, to Puget Sound; the Central Pacific Survey between the 37th-parallel North and the 39th-parallel North from St. Louis, Missouri, to San Francisco, California; the Southern Pacific Survey along the 35th parallel north from Oklahoma to Los Angeles, California; the Southern Pacific Survey across Texas to San Diego, California; and along the Pacific Coast from San Diego, California, to Seattle, Washington.

All were carried out under the direction of Secretary of War Jefferson Davis, the future President of the Confederacy.

We are told the volumes of information that were produced from these surveys were considered to constitute the singlemost important contemporary source of knowledge on western geography and history, and that there value was greatly enhanced by beautifully-illustrated color plates showing the scenery, native inhabitants & fauna and flora of the West.

Let’s take a look at some of the definitions of survey.

Perhaps the most commonly used in our modern culture is the definition of survey which involves a brief interview with someone, for example, with a specific set of questions related to a particular topic to get their feedback.

Then there is the perspective of the definition of survey regarding civil engineering and the activities involved in the planning and execution of surveys gathering information related to all aspects of engineering projects, which is the definition implied in the driving force behind the Pacific Railroad Surveys.

But what about other definitions of survey that might be in play here?

Perhaps, more like some of the definitions shown here – a short descriptive summary; the act of looking or seeing or observing; considering in a comprehensive way; holding a review; and a detailed critical inspection, and not the kind of surveying for civil engineering projects seen in the previous slide as we have been led to believe through historical omission.

What if the Pacific Railroad Surveys were undertaken to explore a ruined landscape surveying, as in “looking at and observing,” everything, including pre-existing rail infrastructure in order to restore it to use once again?

What if the deserts in North America weren’t always deserts?

Other things that Jefferson Davis was credited with during his tenure as Secretary of War:

He promoted the Gadsden Purchase in December of 1853, in which the United States purchased what became southern Arizona and southwestern New Mexico from Mexico…

…overseeing the building of public works infrastructure in Washington, DC, including, but not limited to the Washington Aqueduct, construction of which was said to have started in 1853 under the supervision of Montgomery Meigs and the U. S. Army Corps of Engineers…

…and Davis was involved in getting the Kansas-Nebraska Act passed in 1854 by allowing President Pierce to endorse it before it came up for a vote.

This Act created the Kansas and Nebraska Territories, and repealed the limits on slavery that had been placed on the expansion of slavery in the Missouri Compromise of 1820, and allowed for popular sovereignty, with the citizens of the new territory deciding its slaveholding status.

The passage of this bill led directly to violence in the Kansas Territory, producing a violent uprising known as “Bleeding Kansas” when pro-slavery and anti-slavery activists flooded into the new territories seeking to sway the vote.

Master Mason John Brown, best known for his 1859 ill-fated raid in Harper’s Ferry, West Virginia was involved in events of “Bleeding Kansas.”

The same month that Davis was re-elected for the Senate after his term as Secretary of War was over, in March of 1857, the Supreme Court Ruled in the Dred Scott Case that slavery could not be barred in any territory.

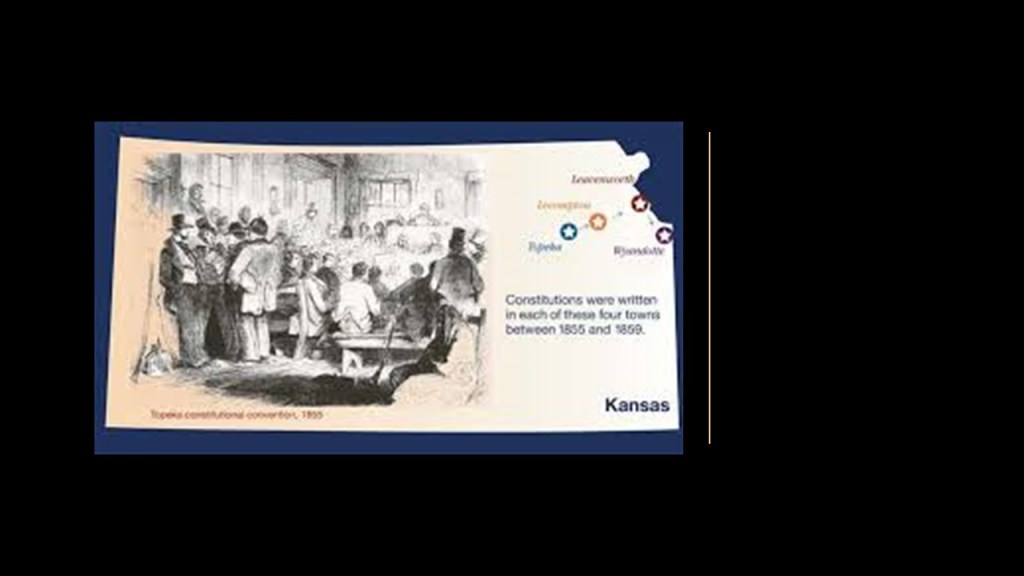

When Jefferson Davis returned to the Senate, which reconvened in November of 1857, the session opened with a debate on the Lecompton Constitution, the second of four constitutions proposed by Kansas, that would have allowed Kansas to have been admitted to the Union as a slave state.

It did not pass because a leading Democratic Senator in the North, Stephen Douglas, believed it did not represent the true will of the people of Kansas, and further undermined the alliance between northern and southern Democrats.

In early 1858, Davis had a severe illness involving the inflammation of his left eye which threatened the loss of his eye.

After spending seven weeks in bed, he went up to Portland, Maine, to recover his health in the summer of 1858.

While Davis was there, he received an honorary Doctor of Law degree from Bowdoin College in Brunswick, Maine, for his contributions as an army officer, Secretary of War, and as a U. S. Representative and Senator.

Davis also felt well enough to give speeches in Maine, Boston, and New York.

These speeches emphasized the common heritage of Americans and the importance of supporting the U. S. Constitution.

His speeches angered some states’ rights supporters in the South, so he clarified his comments when he returned to Mississippi that he felt positive about the benefits of the Union, but also that he felt the Union could be dissolved if states’ rights were violated by one section of the country imposing its will on the other.

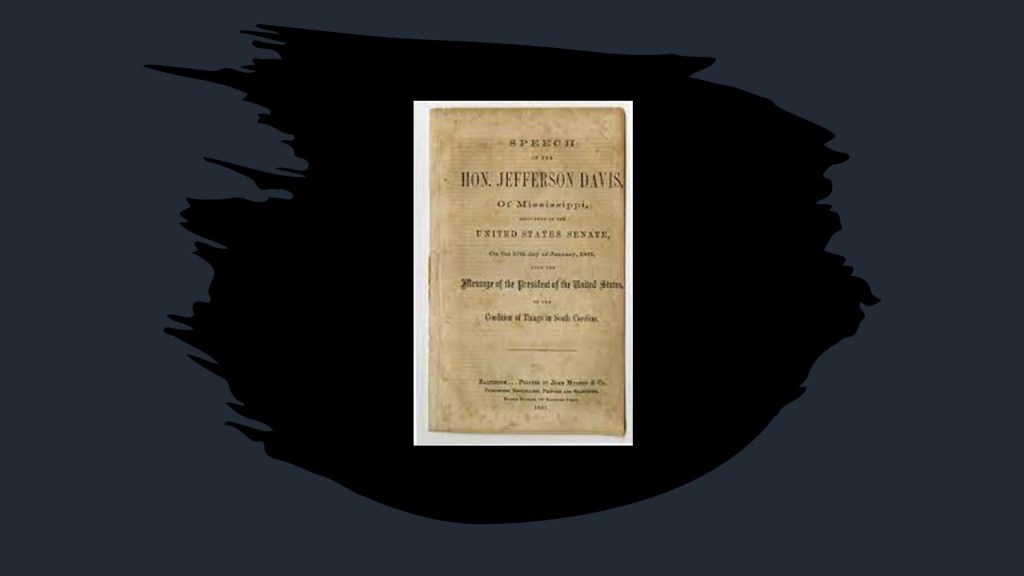

Davis presented a series of resolutions in the Senate in February of 1860 defining the relationship between the states under the Constitution, and he included what he called the Constitutional right of Americans bringing slaves into territories, and these resolutions were seen as setting the Democratic platform for the election that year.

The Democratic Convention vote was split between the Democratic nominee from the North, Stephen Douglas, and from the South, John Breckinridge, and Abraham Lincoln won the 1860 presidential election.

On December 20th of 1860, the State of South Carolina seceded from the Union, and Mississippi followed with the same course of action on January 9th of 1861.

Davis resigned from the Senate on January 21st of 1861, after delivering a speech to the Senate calling it the saddest day of his life, and returned to Mississippi.

Davis notified the Mississippi Governor John C. Pettus that he was available to serve the State, and he was appointed a Major-General in the Army of Mississippi on January 27th of 1861.

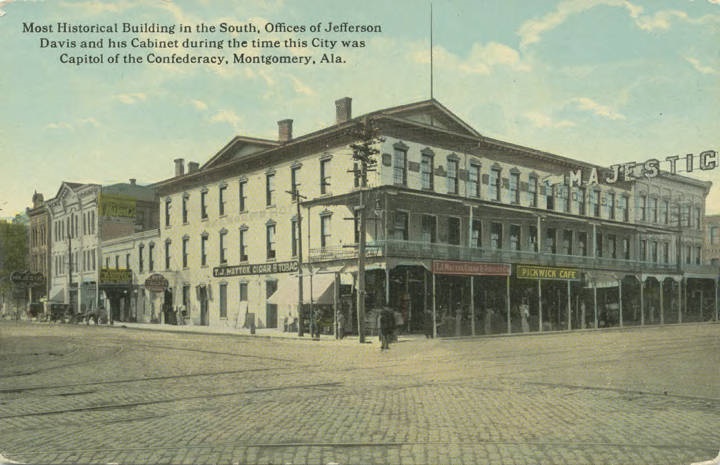

Shortly thereafter, however, on February 10th, he received word that he had been unanimously elected to the provisional Presidency of the Confederacy by a constitutional convention in Montgomery, Alabama, with Alexander H. Stephens as his Vice-President. I learned about Stephens because his statue is one of the two representing Georgia in the National Statuary Hall.

They were provisionally inaugurated on February 18th, and the Confederate Administration was housed in Montgomery’s Exchange Hotel.

We are told that as the southern states seceded, all but four forts had been taken over by state authorities.

Those exceptions were Fort Sumter in Charleston, South Carolina, on the top left; Fort Pickens in Pensacola, Florida, on the top right; and on the bottom left and right in Key West, Fort Zachary Taylor and Fort Jefferson, which is the largest brick masonry structure in the Americas.

All four of these forts were said to have been built after the War of 1812 as a coastal protection from naval invasion…

…in the same way the historical narrative tells us that the Palmerston Forts on the Isle of Wight were a group of forts and associated structures that were built during the Victorian Era in response to a perceived threat of French invasion.

They are called the Palmerston Forts due to their association with Lord Palmerston, the British Prime Minister from 1859 to 1865 who was said to have promoted the idea.

There were approximately 20 of these Palmerston structures along the west and east coast of the Isle of Wight, like Fort Victoria.

The Confederate Congress advised Davis in February of 1861 to send a commission to the U. S. Congress to negotiate the settlement of the disagreements between the Confederate States and the federal government of the United States, including the federal evacuation of these forts.

President Lincoln refused to meet with the Confederate Commission, but they were able to informally meet with Secretary of State William Seward and Supreme Court Justice John Campbell, with Seward hinting without assurance that Fort Sumter would be evacuated.

During this time, President Davis appointed General Beauregard to command the Confederate troops in Charleston.

When Davis was informed that President Lincoln had ordered the resupply of Fort Sumter, he gave the order to General Beauregard to demand the immediate surrender of the fort or destroy it.

In the early morning of April 12th of 1861,when the commanding officer of Fort Sumter refused to surrender, the bombardment of the fort by Confederate forces began.

The fort surrendered on April 14th, with no deaths having resulted from the bombardment according to what we are told, and the American Civil war had begun, with President Lincoln calling for 75,000 volunteer troops, and four more states joined the Confederacy – Virginia, North Carolina, Tennessee, and Arkansas.

Jefferson Davis was the Commander-in-Chief of the Confederate Army, and his military leadership reported directly to him.

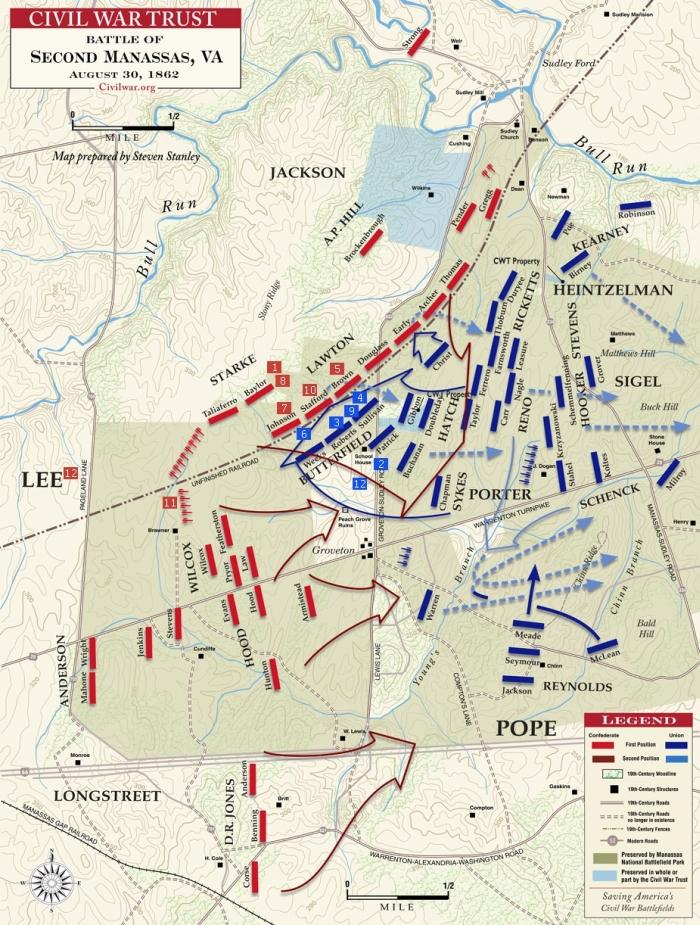

In 1861, the major fighting in the East began after a Union Army advanced into Northern Virginia in July, and was defeated at Manassas in the Battle of Bull Run by two Confederate forces, one under the leadership of General Beauregard and the other under General Johnston.

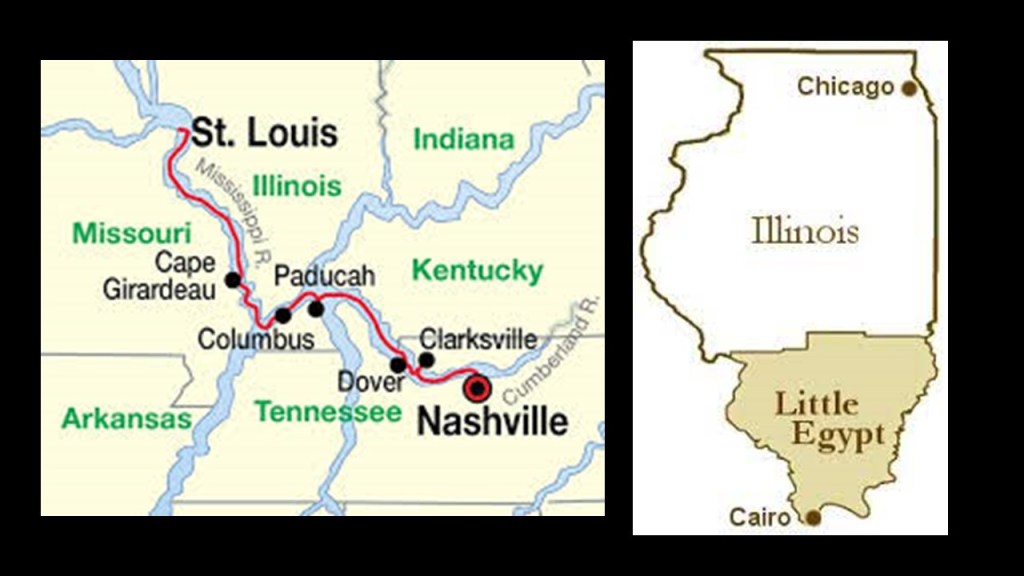

Also in 1861, the Confederacy lost the State of Kentucky, which had wanted to remain neutral until a Confederate Army occupied Columbus, Kentucky, which was supported by President Davis, and Kentucky requested aid from the Union.

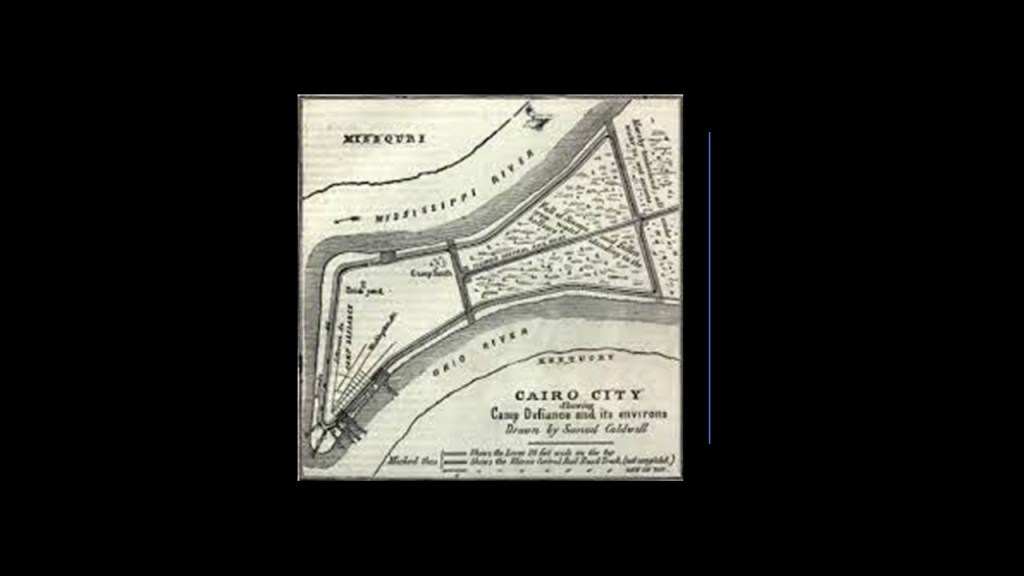

Interesting to note that Columbus Kentucky is located at the confluence of the Mississippi and Ohio Rivers, very close to Cairo, Illinois, in a part of the country nicknamed “Little Egypt.”

The Confederate Army was said to have constructed a fort in Columbus, which it is interesting to note will be in the path of totality for the 2024 total solar eclipse as it is close to Carbondale, Illinois, the crossing point of both the 2017 & 2024 solar eclipses…

…and is also close to the Giant City State Park in Makanda, Illinois, just south of Carbondale, and also on the solar eclipse path of totality.

It is also interesting to note that a primary attraction at the Columbus-Belmont State Park, the historical location of the fort, are the remains of a mile-long giant chain and its anchor estimated to weigh between 4- to- 6-tons that was constructed under the direction of Confederate General Leonidas Polk, we are told, in 1861 that stretched across the Mississippi River between the fortification in Columbus, and Camp Johnson in Belmont, Missouri.

This defensive strategy didn’t work too well, as by March 3rd of 1862, Union troops under then Brigadier-General Ulysses S. Grant occupied the area and took down most of the chain.

This was after Forts Donelson and Henry in Tennessee were captured by Union Forces in February of 1862.

All of this led to the collapse of Confederate defenses, and in the Spring of 1862, not only Kentucky, but also Memphis and Nashville were lost to the Confederacy, as well as control of the Tennessee and Cumberland Rivers.

Jefferson Davis was formally inaugurated as President of the Confederacy on February 22nd of 1862.

Davis vetoed a bill in March of 1862 to create a Commander-in-Chief for the Confederate Army, though he selected General Robert E. Lee to be his military advisor.

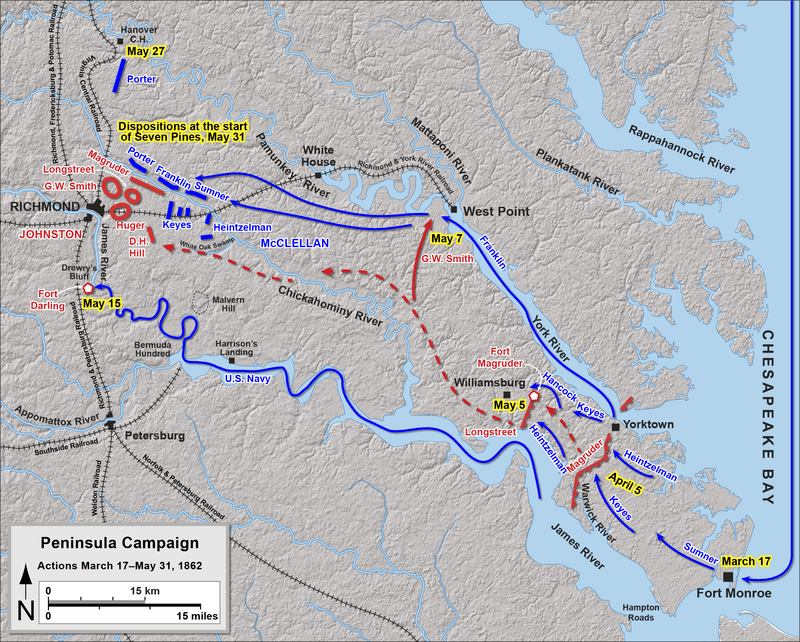

In March of 1862, the Union Army began a major attack on the Virginia Peninsula, where Hampton Roads is located, and 75-miles, or 121-miles, from Richmond.

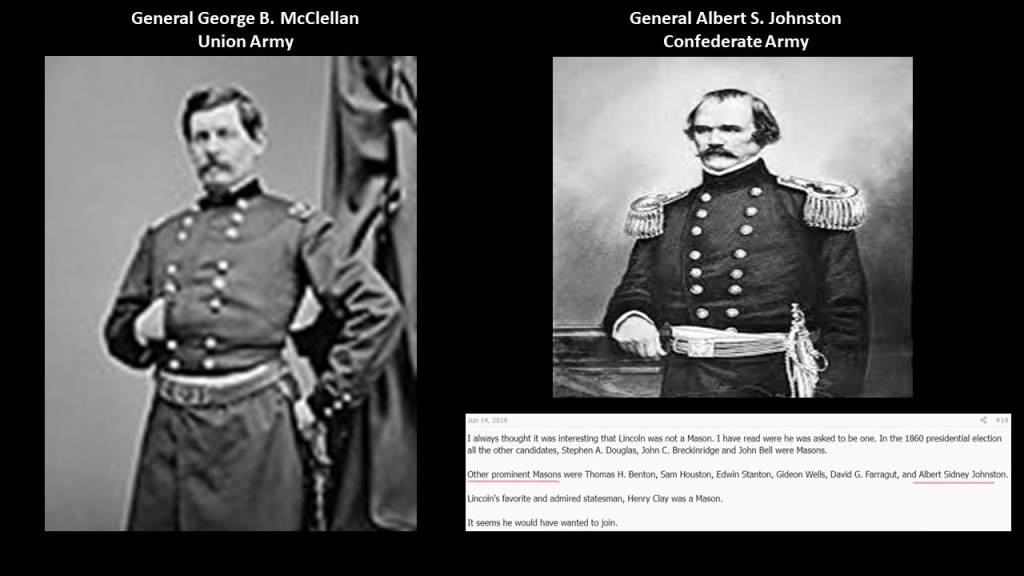

General Albert S. Johnston commanded the Confederate Army near Richmond and did not follow the command to take a stand at Yorktown, Virginia, and instead withdrew from the Peninula to engage in battle with the Union Army under the command of General George McClellan at what became known as the “Battle of Seven Pines” or the “Battle of Fair Oaks Station on May 31st and June 1st of 1862.

Johnston had the men in his army protecting the defensive works of Richmond.

McClellan’s Army of the Potomac had used the Richmond and York River Railroad to bring in heavy siege artillery to the outskirts of Richmond just prior to the battle.

We are told the result of the battle was inconclusive, and the closest advance of Union forces to Richmond in this offensive.

It was the largest battle in the Eastern Theater of the Civil War up until that time.

It also resulted in injury to General Albert S. Johnston, leading to his replacement by General Robert E. Lee as the Confederate Commander

General Robert E. Lee led what was known as the Seven Days Battles, called a Confederate Victory, from June 25th to July 1st of 1862, near Richmond which drove General McClellan’s Union Army away from Richmond and into a retreat down the Virginia Peninsula ending the Peninsula Campaign, though McClellan’s troops landed at Harrison’s Landing in Virginia on the James River, protected by Union gunboats.

In August of 1862, Lee’s troops triumphed over a Union Army trying to move into Manassas, Virginia, at the Second Battle of Bull Run…

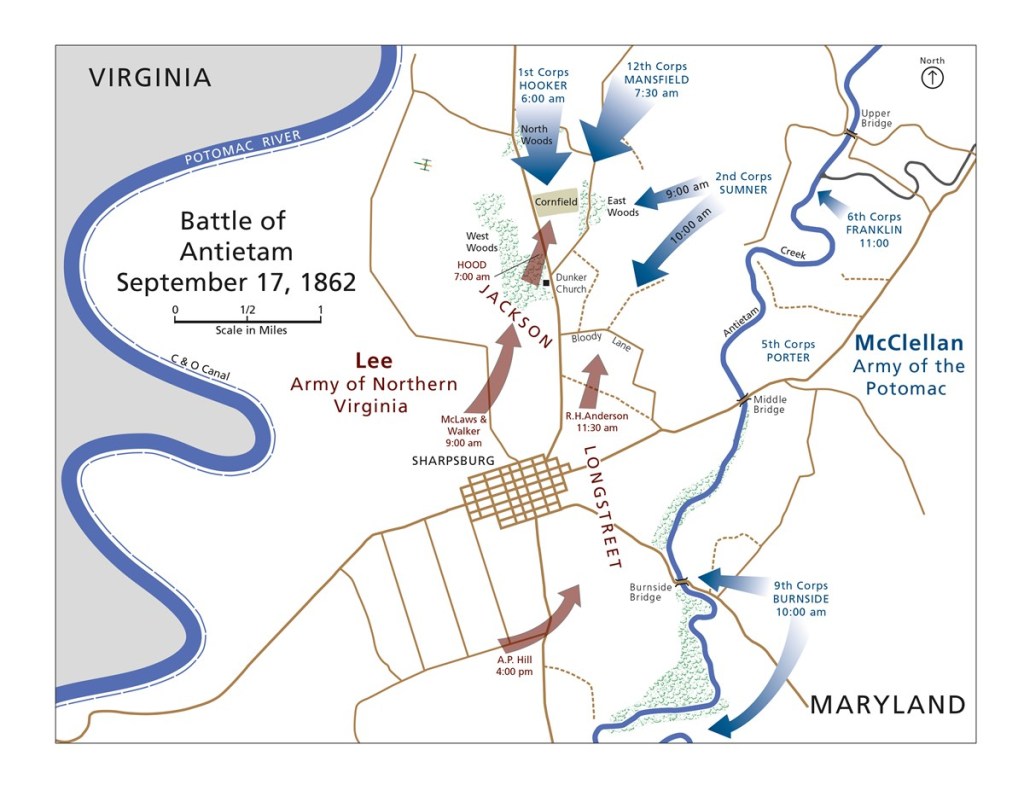

…but Lee withdrew from Maryland after a stalemate at the Battle of Antietam in September of 1862, though a major turning point in the Union’s favor.

In 1863, the Emancipation Proclamation was issued by President Lincoln on January 1st, in which he changed by executive order the legal status of the slaves in Confederate States to free.

Jefferson Davis saw this as the desire of the North to destroy the South, and as an incitement to rebellion of the enslaved people of the South.

Davis addressed the Confederate Congress, saying the emancipation proclamation was a crime against humanity that would be reviled throughout history.

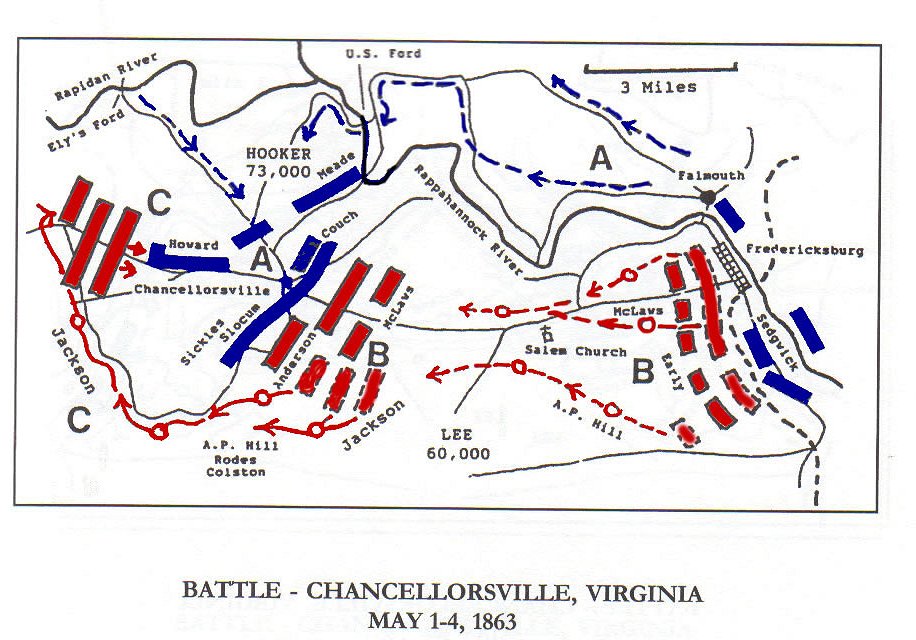

General Lee had broken up a Union invasion into Virginia in May of 1863 at the Battle of Chancellorsville…

…but lost a big one at the Battle of Gettysburg between July 1st and July 3rd of 1863, when General Lee’s troops invaded Pennsylvania.

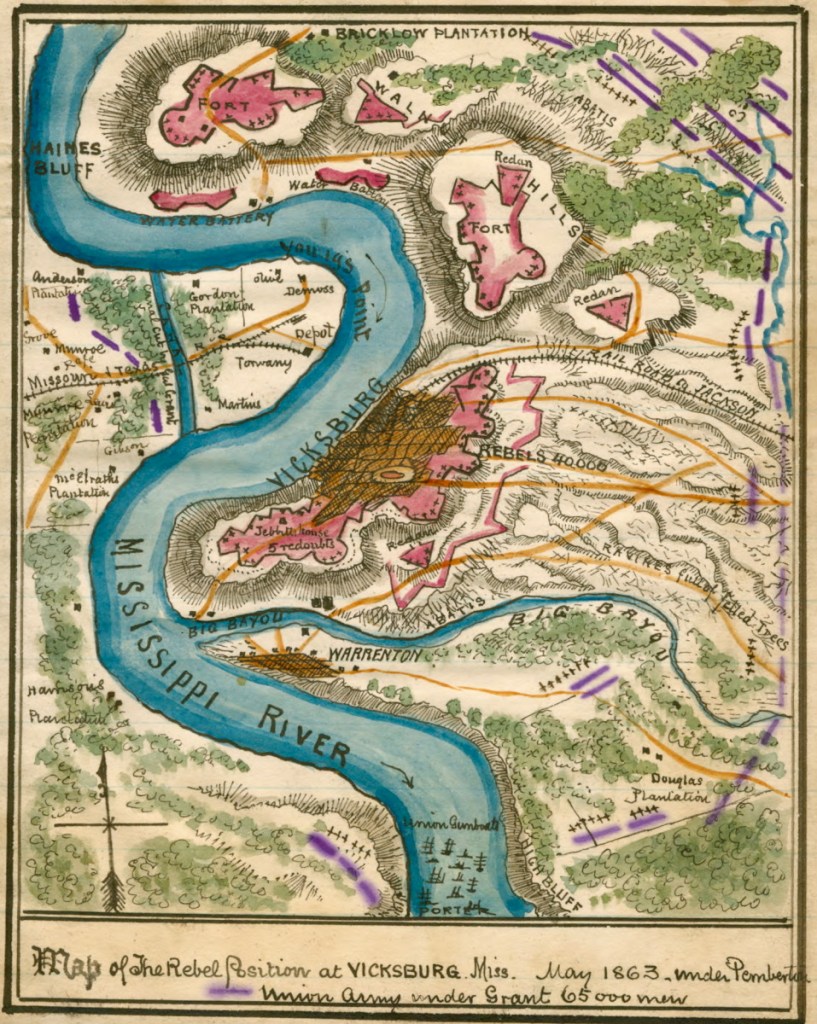

The Battle of Gettysburg had the largest number of casualties during the war, and described as the Civil War’s turning point along with the Union victory following the Siege of Vicksburg in Mississippi, which took place between May 18th and July 4th of 1863.

I mentioned previously that Vicksburg was a short distance north of the Davis plantations just north of Davis Bend.

Vicksburg was the last major Confederate stronghold on the Mississippi River, and cut-off the Confederacy’s Trans-Mississippi Department from the rest of the Confederate States.

In past research, I have already found a lot of anomalies here.

First, the Siege of Vicksburg and its aftermath.

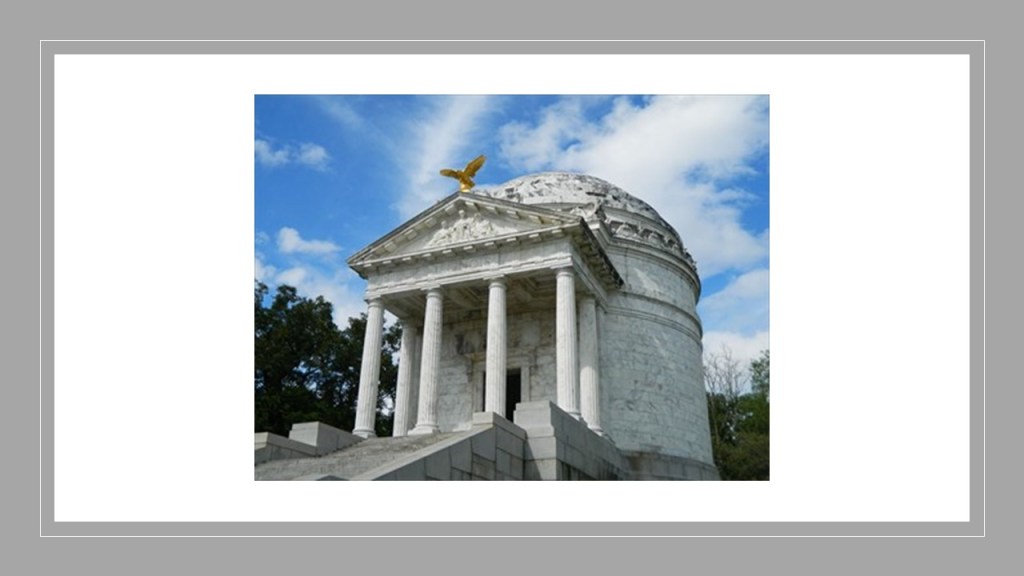

We are told that after the Vicksburg National Military Park was established in 1899, the nation’s leading architects and sculptors were commissioned to honor the soldiers and sailors from their respective states that fought in the Vicksburg campaign, leading it to be called the “Art Park of the World” with more than 1,400 monuments found throughout the park.

Like the Mississippi Memorial…

…the Michigan Memorial…

…and the Illinois State Memorial.

The Shirley House is said to be the only-surviving wartime structure inside the Vicksburg National Military Park.

This is a wartime picture of the Shirley House circa 1863, with what is described as the camp of the 45th Illinois Infantry behind it.

But there are things going on in this photo that don’t make sense to me.

Why all the digging and entrances?

Apparently during the Siege of Vicksburg, the people of the city dug caves into the sides of hills to get out of harm’s way from the hail of iron that was coming their way from Union forces.

But why do the caves in Vicksburg look like the 49er gold-mines in California’s Gold Rush country?

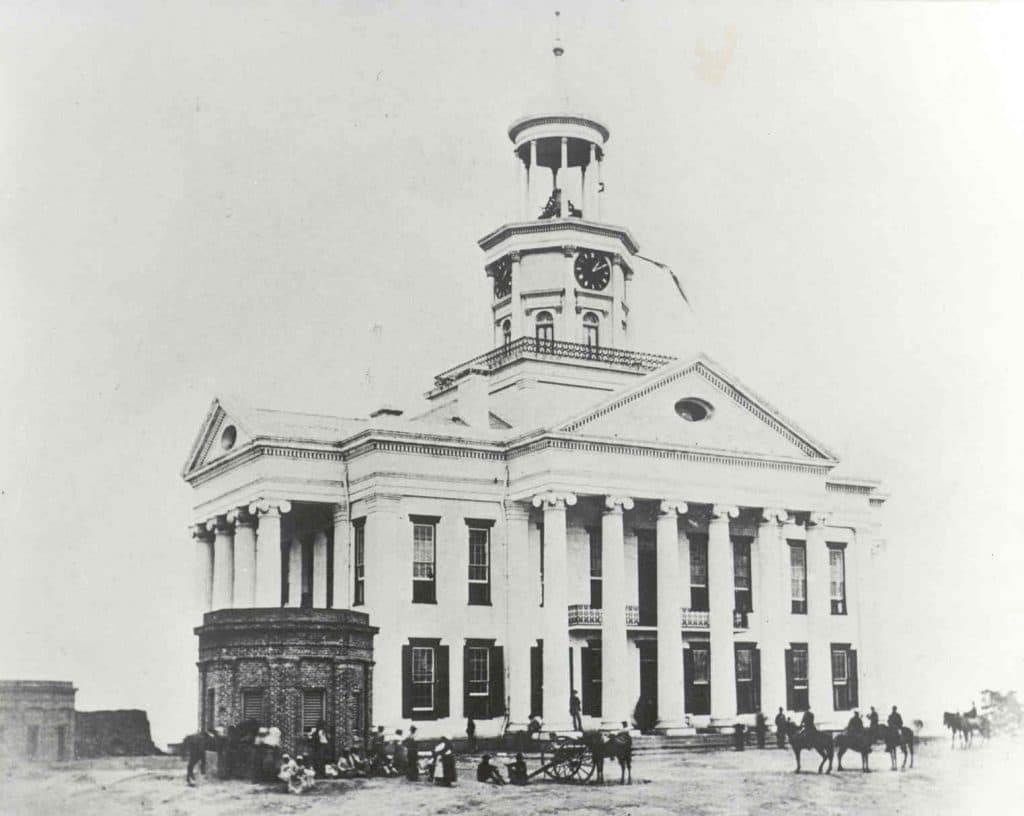

This photo was notated as Union soldiers on the lawn of the Warren County Courthouse after the siege.

It was said to have been constructed between 1858 and 1860.

Interesting to note the contrast between the size of the soldiers and that of the courthouse.

Considered to be Vicksburg’s most historic structure, a museum is operated within the old courthouse today.

The mud-flooded-looking Washington Hotel in Vicksburg was said to have been used as a military hospital during the Civil War.

There was a castle in Vicksburg which was said to have been built in the 1850s, including a moat, but it was destroyed by the Union Army and the site turned into an artillery battery.

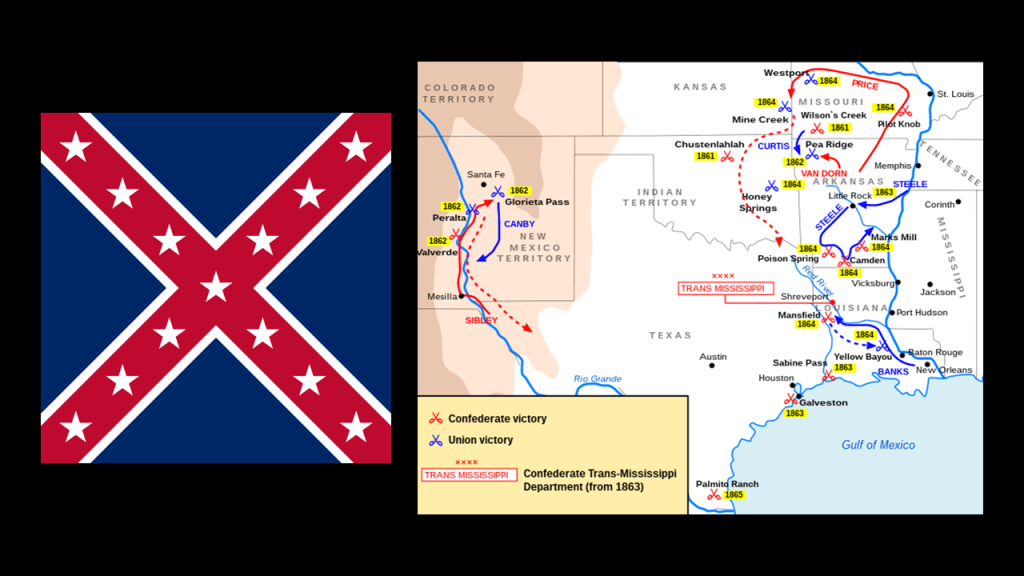

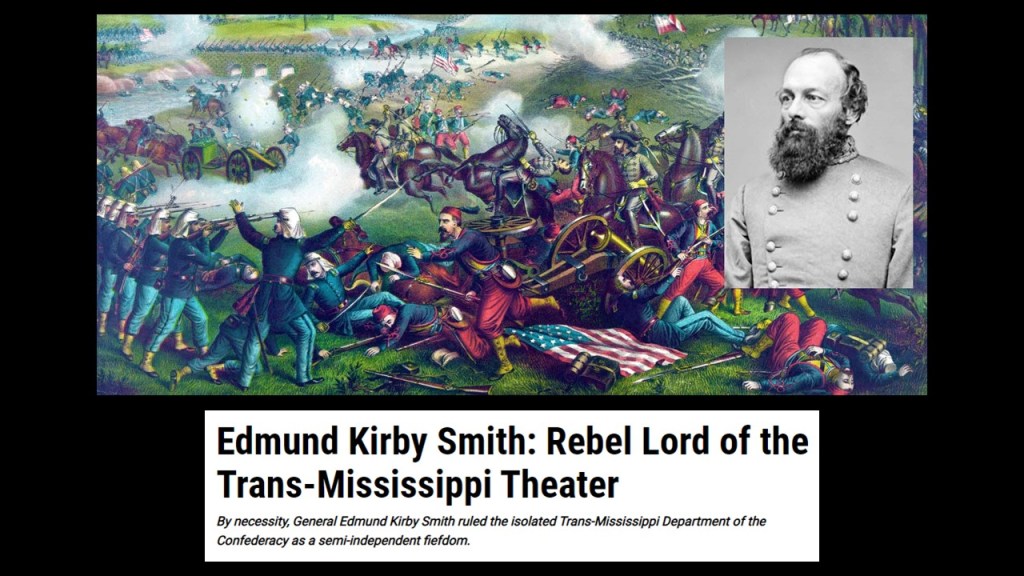

Then there is the Trans-Mississippi Department.

Edmund Kirby Smith was a senior officer of the Confederate States Army who commanded its Trans-Mississippi Department between 1863 and 1865, and represents the State of Florida in the National Statuary Hall in the U. S. Congress.

The Trans-Mississippi Department of the Confederate States Army was comprised of Arkansas, Texas, Missouri, western Louisiania, Arizona Territory and Indian Territory.

After the Union forces captured Vicksburg, Mississippi and Port Hudson in Louisiana…

…Edmund Kirby Smith’s forces were cut off from the Confederate Capital of Richmond, Virginia.

As a result of being cut-off from Richmond, Smith commanded and administered a nearly independent area of the Confederacy, and the whole region became known as “Kirby Smithdom.”

What was really going on here during that time?

After all, this was the heart of the ancient Washitaw Empire of North America, that most people have never heard of it because it was removed from our collective awareness.

At any rate, in our historical narrative, the Confederate General Edmund Kirby Smith surrendered the Trans-Mississippi Department on May 26th of 1865 on board the U. S. S. Fort Jackson on Galveston Bay in Texas to the Union Major General Edward Canby, approximately eight-weeks after General Robert E. Lee’s surrender to General Ulysses S. Grant in Virginia.

Though Davis tried to find ways to continue fighting, the Confederate Government was officially dissolved on May 5th of 1865 in Washington, Georgia.

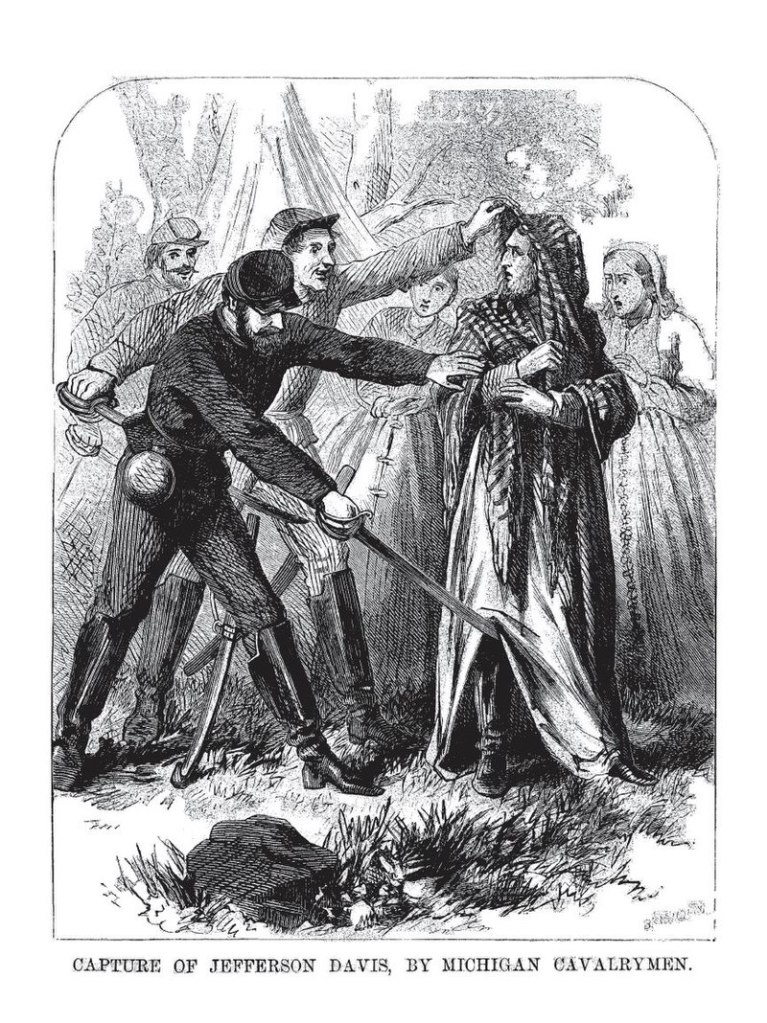

Davis was captured by Union soldiers where he was camped out near Irwinville, Georgia, four-days later.

Jefferson Davis was imprisoned at Fort Monroe on the southern tip of the Virginia Peninsula at Hampton Roads.

Davis was released on bail posted by wealthy friends like Cornelius Vanderbilt after two-years, and he and his family relocated to Lennoxville, Quebec.

President Andrew Johnson issued a proclamation at Christmas in 1868 granting amnesty and pardon to Davis, and all participants in the rebellion.

Jefferson Davis died on December 6th of 1889 in New Orleans, where his body lay in-state at the New Orleans City Hall.

The funeral held for him in New Orleans was said to have been one of the largest funerals held in the South, and the procession attended by an estimated 200,000 people.

His remains were ultimately interred at the Hollywood Cemetery in Richmond, Virginia.

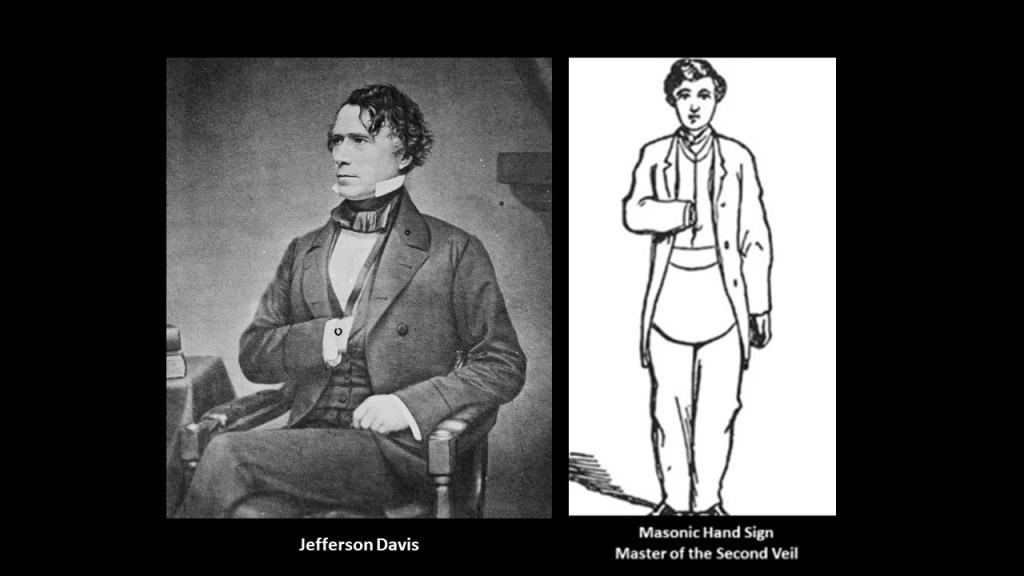

I tried to find out if Jefferson Davis was a Freemason, and received some results in my initial search, from others and Davis himself, saying that he himself was not a mason.

But I did find this picture of Jefferson Davis with his right hand fully-tucked into his jacket in an internet search, which is the masonic hand sign signifying “Master of the Second Veil…”

…and, like President Gerald Ford, President of the Confederacy Jefferson Davis was prominently featured in the “Knight Templar” Magazine.

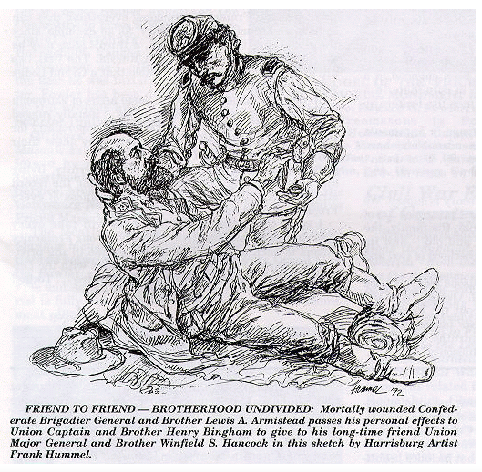

There were Freemasons on both sides of the conflict, like this illustration signifying masonic brotherhood between Confederate Brigadier General Lewis Armistead and Union Captain Winfield Hancock at Gettysburg.

I found the same thing when I was researching Samuel Adams for Massachusetts in the National Statuary Hal.

He was called the “Father of the American Revolution,” and there were Masonic brethren on boths sides of the conflict and also involved at a high level.

I found Samuel Adams mentioned as a Freemason in an article from June of 2009 on the antiquesandhearts.com website about the Grand Lodge of Masons in Massachusetts celebrating 275 years of brotherhood.

The article mentioned things like the Green Dragon Tavern in Boston being the unofficial Headquarters of the American Revolution…

…as well as being the meeting place for the Grand Lodge of Massachusetts, which had purchased the Green Dragon Tavern in 1764, and used it as a meeting place until 1818.

Also mentioned in this article is that it was the origin point for the Boston Tea Party participants and Paul Revere’s midnight Ride, as well as mentioning that there were Freemasons among the British soldiers occupying Boston, which are called “Brethren.”

So, who’s their loyalty really to?

Are the Freemasons actually playing both ends against the middle in a massive deception to bring in the New World Order agenda…

…using the stolen legacy of the real Master Masons?

I definitely think so ~ there is absolutely no doubt in my mind!

James Z. George is the other person representing the State of Mississippi in the National Statuary Hall.

James Zachariah George was a lawyer, author & Confederate politician and military officer.

He was born in October of 1826 in Monroe County, Georgia.

His father died when he was young, and he moved to Mississippi with his mother and stepfather when he was eight.

He attended school in Carroll County, Mississippi, and this would have been in the time-frame that Greenwood Le Flore, the last Choctaw principal chief east of the Mississippi River who resided in Carroll County, was the lead negotiator for the Choctaw on the 1830 Treaty of Dancing Rabbit Creek, the first removal treaty under the 1830 Indian Removal Act in which the remaining Choctaw lands in Mississippi were ceded to the United States, and the Choctaw were removed to Indian Territory out west.

This was Le Flore’s mansion named “Malmaison” in Carroll County.

Carroll County in Mississippi, was named after Charles Carroll of Carrollton, one of Maryland’s statues in the National Statuary Hall.

James Z. George entered the military at some point, and served under then Colonel Jefferson Davis at the Battle of Monterey in September of 1846 during the Mexican-American War.

After returning to Mississippi from the Mexican-American War, George read for the law and was admitted to the Bar.

He became a reporter of the Supreme Court of Mississippi, and prepared a 10-volume digest of its cases over the next 20-years.

George was a member of the Mississippi Secession Convention, along with Jefferson Davis, and was a signatory on the Mississippi Secession Ordinance.

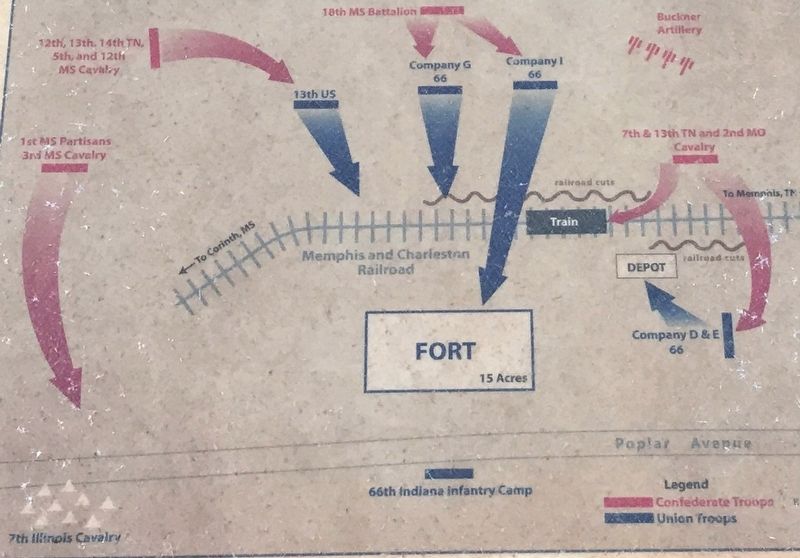

George was a Confederate Colonel in the 5th Mississippi Cavalry, and he was captured in the Battle of Collierville in Tennessee during the Civil War, and spent two years in a Prisoner-of-War camp, where we are told he conducted a law course for his fellow prisoners.

He returned to Mississippi upon his release and resumed practicing law.

In 1879, George was appointed to the Supreme Court of Mississippi, and selected to become the Chief Justice.

Then from 1881 until his death in August of 1897, George represented the State of Mississippi in the United States Senate.

During his time in the Senate, George helped frame the future Sherman Anti-Trust Act of 1890, in which the rule of free competition was prescribed among those engaged in commerce, and specifically prohibiting the creation of monopolies.

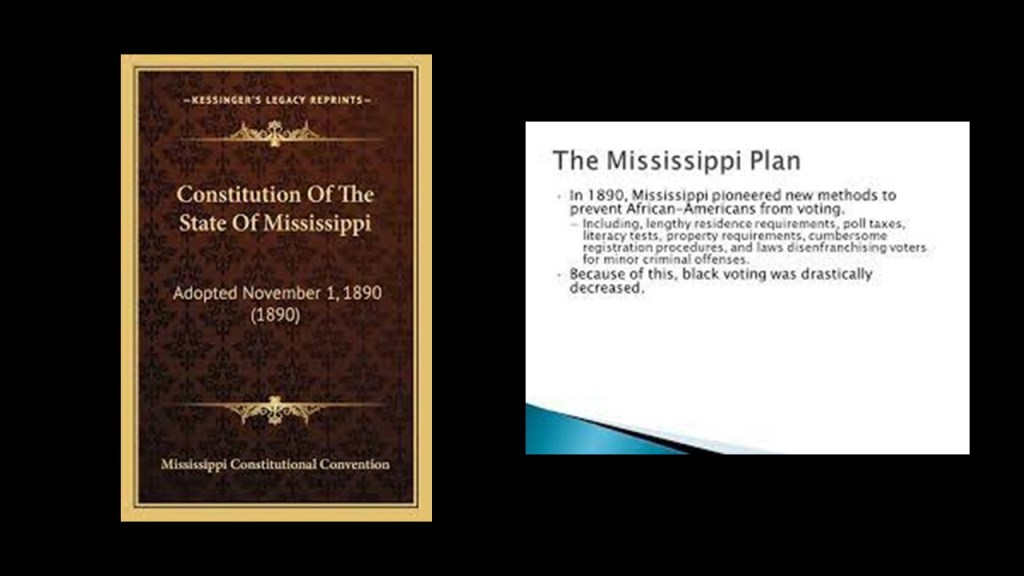

At the same time, on the other hand, George was also involved in finding ways to legally disenfranchise the black citizens of Mississippi, and was a leading figure during the Mississippi Constitutional Convention of 1890.

The Mississippi Constitution of 1890 is one of four constitutions Mississippi has had since becoming a state in 1817.

While it is the current constitution for the state of Mississippi, it has been amended and updated one-hundred times since its adoption in 1890.

This constitution contained provisions to prevent the state’s black citizens from voting.

The provisions preventing them from voting weren’t repealed until 1975, and that was after the U. S. Supreme Court had ruled them unconstitutional in the 1960s.

James Z. George died in Mississippi City, Mississippi, in August of 1897, where he had gone for health treatment.

He was buried in the Evergreen Cemetery in North Carrollton, Mississippi.

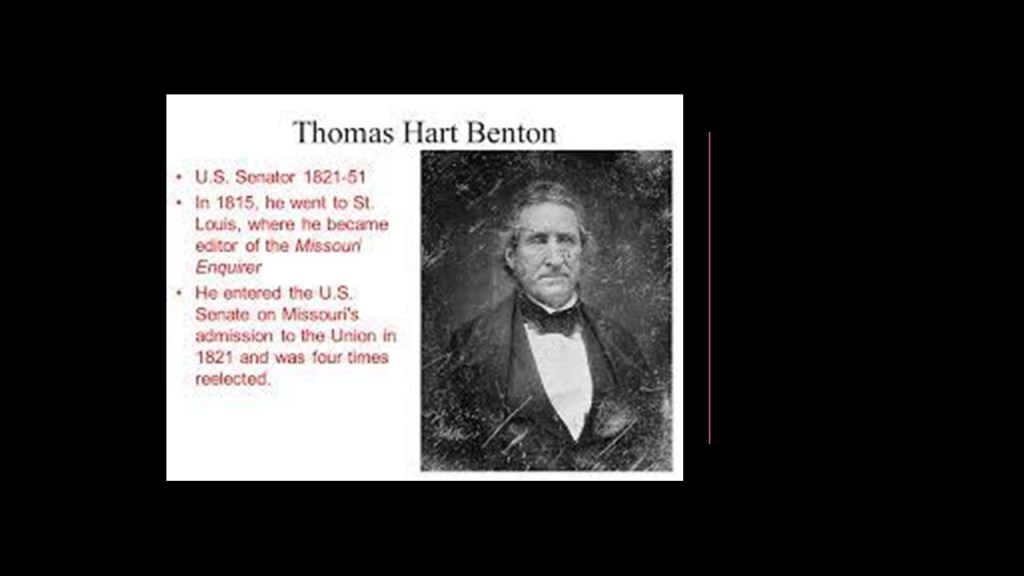

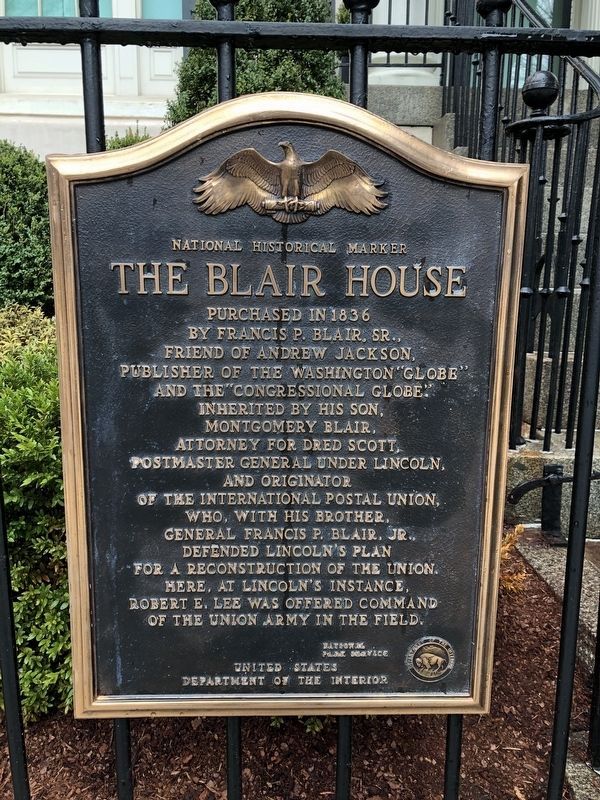

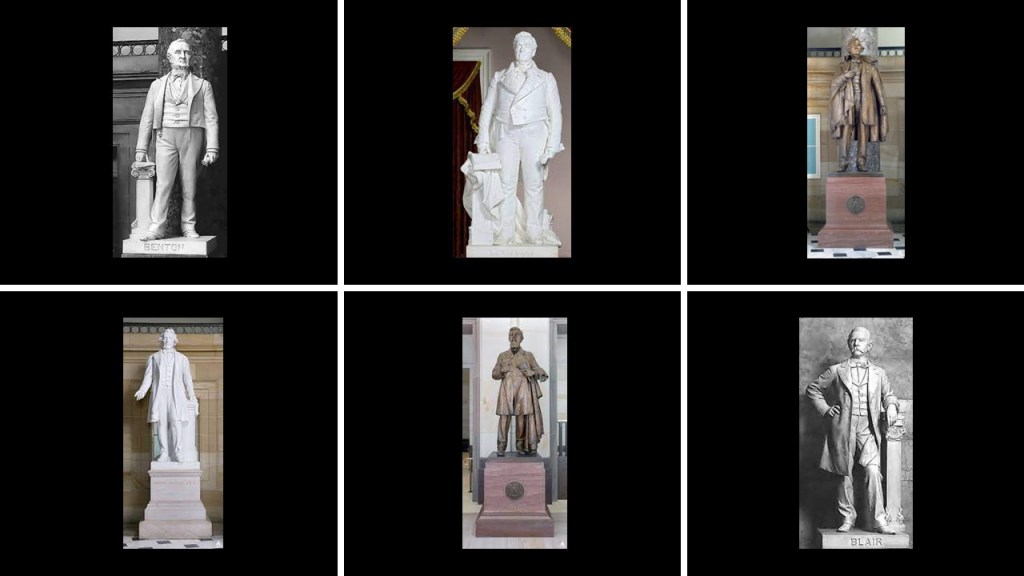

Lastly for this post, the State of Missouri is represented in the National Statuary Hall by Thomas Hart Benton and Francis Preston Blair, Jr.

Thomas Hart Benton was a United States Senator from Missouri, and he was a champion of westward expansion, a cause that became known as “Manifest Destiny.”

He served in the U. S. Senate between 1821 and 1851, becoming the first Senator to serve five-terms.

Thomas Hart Benton was born in March of 1782 near the town of Hillsborough, the county seat Orange County in North Carolina.

His father Jesse was a wealthy landowner and lawyer, and he passed away in 1790.

Apparently Thomas Hart Benton studied law at the University of North Carolina, but was expelled in 1799 for stealing money from other students, after which he managed the family estate for awhile.

The young Benton and his family moved west to a 40,000-acre, or 160-km-squared, holding near Nashville, Tennessee, upon which he was said to have established a plantation with schools, churches, and mills.

It was said that his experience as a pioneer during this time gave him a devotion to Jeffersonian Democracy during his political career.

Benton resumed studying law and was admitted to the Tennessee Bar in 1805, and became a state senator in 1809.

He caught Andrew Jackson’s eye, Tennessee’s First Citizen, and Jackson made Benton his personal assistant with a commission as a Lieutenant Colonel at the outbreak of the War of 1812.

He was assigned to represent Jackson’s military interests in Washington, DC.

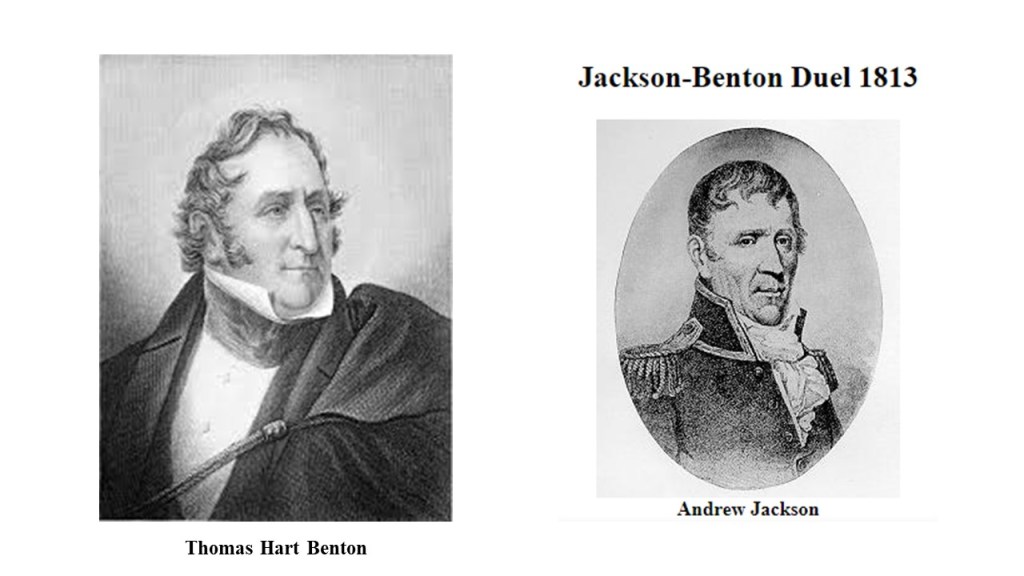

But this relationship turned sour somewhere along the way, and in September of 1813, Thomas Hart Benton and his brother Jesse engaged in duel with Jackson in the City Hotel in Nashville, where Jackson was seriously wounded by a gunshot wound in the shoulder.

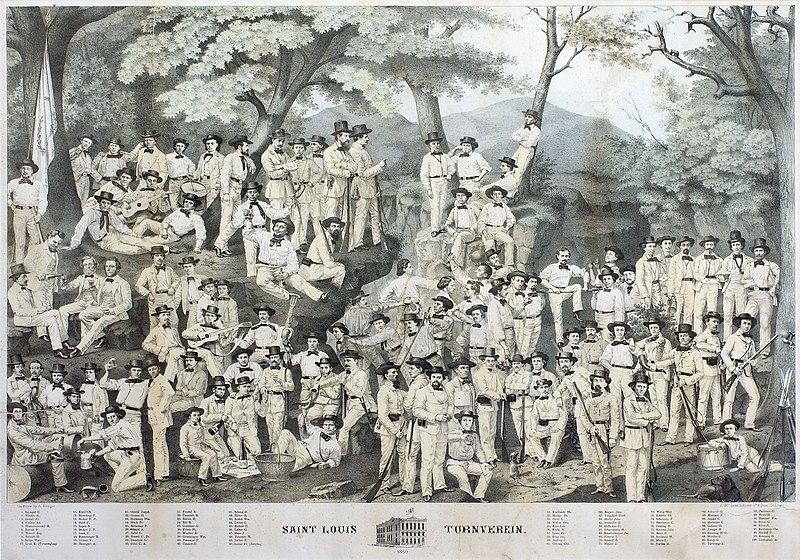

In 1815, Benton moved to St. Louis, Missouri, where he practiced law and established and became editor of the Missouri Enquirer, the second major newspaper west of the Mississippi River.

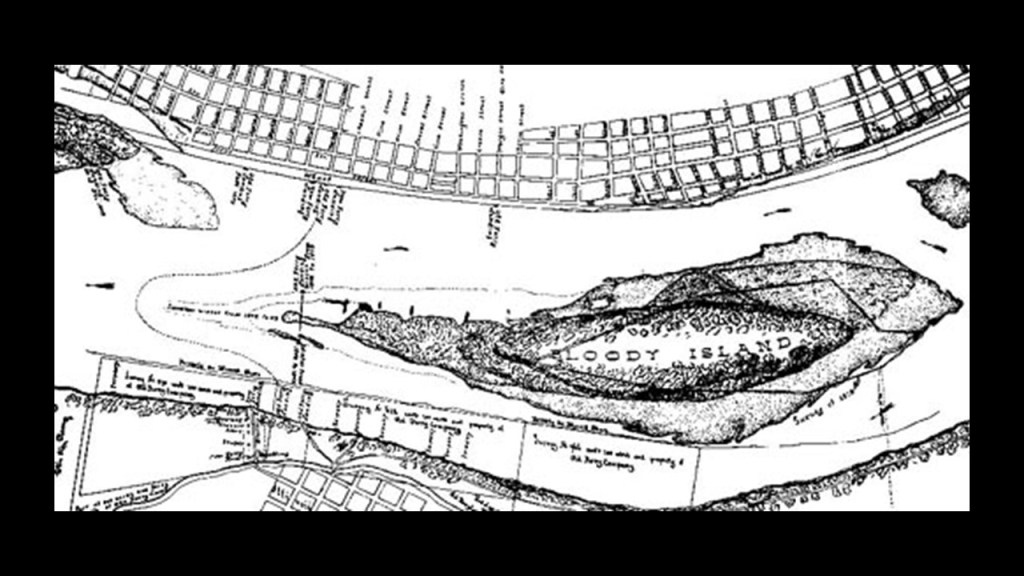

Then, in 1817, Benton and another attorney, Charles Lucas, got cross-wise with each other initially during a court case in which they were opposing each other, and the resulting animosity led to Benton killing Lucas in a duel on a place called “Bloody Island,” a neutral little island in the Mississippi River between Missouri and Illinois where duellists would go because it was not under the control of either state.

We are told that Bloody Island first appeared above-water in 1798, and posed a problem to the St. Louis Harbor.

Then in 1837, Capt. Robert E. Lee, who was then a part of the Army Corps of Engineers, established a system of dikes and dams that washed out the channel and joined the island to the Illinois shore.

The Miami people of the Great Lakes Region stopped on Bloody Island when they were being forcibly removed from their homelands in 1846, where their oral history relates they buried an elder and an infant somewhere in the vicinity.

Interesting to note that the south end of Bloody Island is located at the site of a train-yard.

We are told that there was a ferry service that had been developed that operated between East St. Louis and St. Louis starting in the early 1800s that eventually developed the train-yards in the 1870s that carted train cars across the Mississippi River, using an 8-horse-team to power the propulsion, until the Eads Bridge, a combined road-and-railway-bridge opened in 1874, which is located between LaClede’s Landing on the northside, and the grounds of the Gateway Arch on the southside.

Construction of the bridge was said to have started in 1867 (two-years after the end of the American Civil War) and completed in 1874.

Bloody Island was once the site of a huge network of railroad tracks, but with the exception of a few rail-lines in use, the area has largely returned to nature.

And this location is in close proximity not only to the Gateway Arch, but to the Busch Stadium as well, home of the St. Louis Cardinals Major League Baseball team.

Hmmm…I wonder what they are not telling us about our true history and about this place!

When the Missouri Compromise of 1820 resulted in the Missouri Territory becoming a state, Benton was elected as one of its first U. S. Senators.

The Missouri Compromise was federal legislation that balanced the desires of northern states to prevent the expansion of slavery in the country, with those of southern states seeking to expand it.

It admitted Missouri as a slave state, and Maine as a free state, and prohibited slavery in the remaining Louisiana Purchase lands north of the 36.5-degree parallel.

Andrew Jackson was one of four candidates for President, along with Henry Clay and William H. Crawford, in the 1824 Election, with John Quincy Adams ultimately winning the election without a majority of the electoral or popular vote.

Andrew Jackson again ran for the Presidency in 1828, running against sitting-President John Quincy Adams, and this time he was successful, and ended-up serving two presidential terms.

Apparently Thomas Hart Benton and Andrew Jackson set aside their differences and joined forces over the issue of money and banking.

Benton, nicknamed “Old Bullion,” was in favor of “hard money,” like gold coins and/or bullion.

Jackson and Benton were both against the Second Bank of the United States, which was a federally-authorized national bank in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, from when it was chartered in 1816.

It was a private bank with public duties, handling all fiscal transactions for the U. S. Government, accountable to Congress and the Treasury Department.

Four-thousand private investors held 80% of the bank’s capital, of which three-thousand of those investors were European, with a bulk of the stocks held by a few hundred wealthy Americans.

Kinda sounds familiar….

The “Bank War” started in 1832 during the Jackson Presidency, and was a political struggle that occurred over the issue of rechartering the bank, and a conflict that involved the Federal Government over the State Sovereignty in the U. S. political system.

The Second Bank of the United States had the exclusive right to conduct banking on a national scale, with the vision of stabilizing the economy, providing a uniform currency, and strengthening the federal government.

Jackson and Jacksonian Democrats saw the public-private organization of Second Bank as favoring merchants and speculators over the rest of society, and as unconstitutional, with the bank’s charter violating state sovereignty.

In 1832, President Jackson vetoed the bill Congress had passed to reauthorize the Second Bank’s charter, and quickly removed federal deposits from the bank, arranging for their distribution to state banks in 1833.

President Jackson was censured by the Senate in 1834 for cancelling the Second Bank’s Charter, for which Benton successfully led the campaign to remove Jackson’s censure from the official record in 1837.

The Second Bank never secured its recharter, and it was liquidated in 1841.

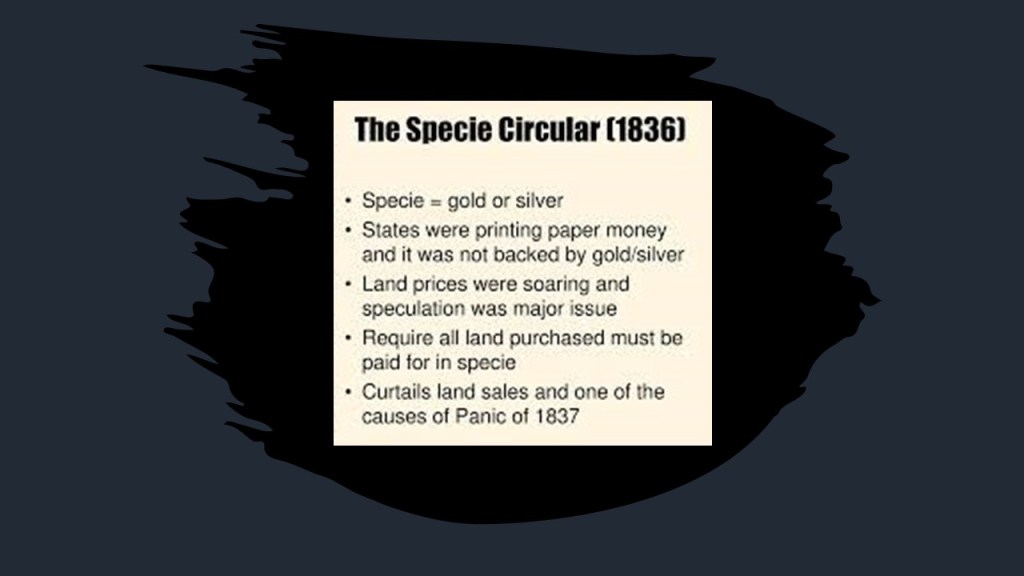

President Jackson issued an executive order in 1836 known as the “Specie Circular,” which required payment for government land to be made in gold and silver, and a reaction to concerns about excessive speculation of land that took place after the implementation of the 1830 Indian Removal Act, which also took place during President Jackson’s Administration as mentioned previously in this post.

Many at the time, and later historians, blamed the “Specie Circular” for the Panic of 1837, a financial crisis which touched off a major depression lasting until the mid-1840s, where wages, prices and profits went down, unemployment went up, and westward expansion was stalled.

We are told that by 1850, the economy was booming again because of the increased specie flows from the California Gold Rush.

As Senator, Benton’s main concern was westward expansion, or what became known as “Manifest Destiny,” a 19th-century belief that the United States was destined by God to expand its dominion and spread democracy and capitalism across the entire continent.

Benton was the major reason for the sole administration of the Oregon Territory, which had been jointly-occupied by the United States and Great Britain since the Anglo-American Convention of 1818.

Benton chose the current 49th-parallel border Between the U. S. and Canada set by the Oregon Treaty in 1846.

Benton pushed for more exploration of the West, including support for the numerous treks of his son-in-law, explorer and cartographer John C. Fremont…

…to get public support for the transcontinental railroad…

…and for greater use of the telegraph for long-distance communication.

Benton was the Legislative right-hand man for President Andrew Jackson, as well as the next President, Martin van Buren.