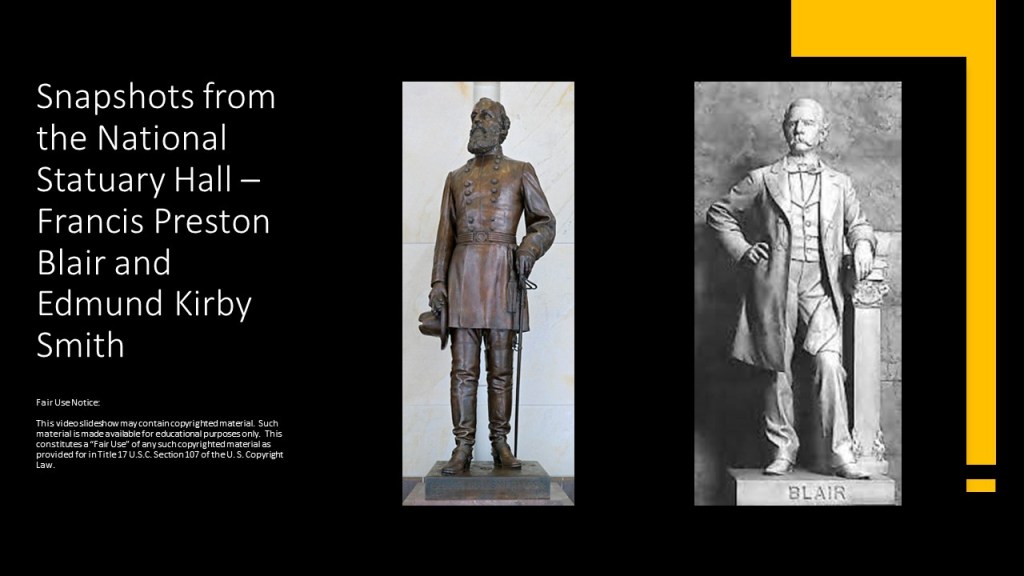

In this series called “Snapshots from the National Statuary Hall,”I am bringing forward unlikely pairs of historical figures represented in the National Statuary Hall at the U. S. Capitol who have things in common with each other.

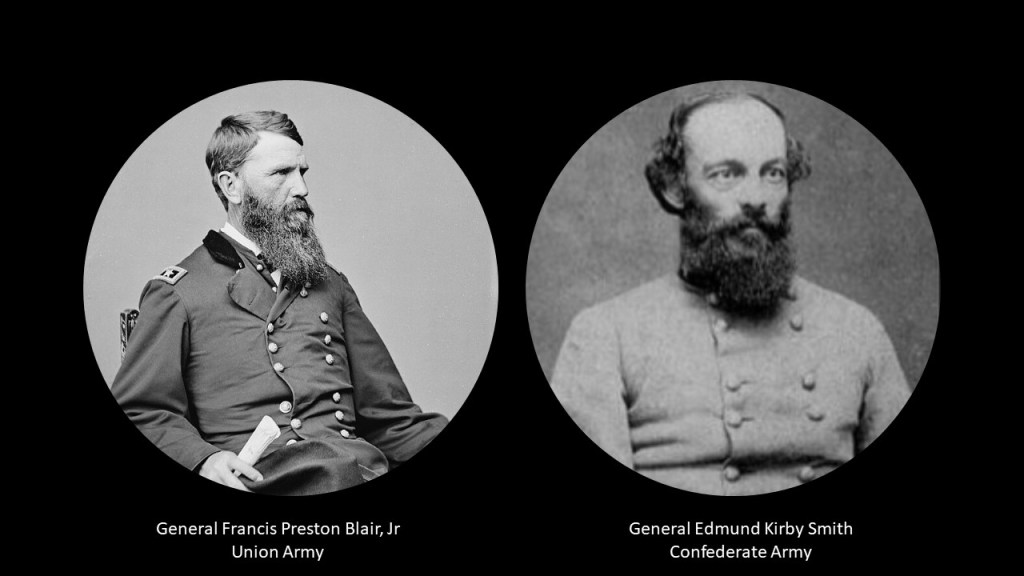

In this post, I am pairing Francis Preston Blair, Jr, of Missouri, a Union Major General during the Civil War, with Edmund Kirby Smith of Florida, a senior officer of the Confederate States Army.

So far in this series, I have paired Michigan’s Gerald Ford, a former President of the United States, and Mississippi’s Jefferson Davis, the former President of the Confederate States of America, and both men featured on the cover of the “Knight Templar” Magazine,; Dr. Norman Borlaug, Ph.D, often called the “Father of the Green Revolution; and Colorado’s Dr. Florence R. Sabin, M.D, a pioneer for women in science, both of whom worked for the Rockefeller Foundations; Louisiana’s controversial Socialist Governor, Huey P. Long, and Alabama’s Helen Keller, a deaf-blind woman who gained prominence as an author, lecturer, Socialist activist; Henry Clay, attorney and statesman from Kentucky, and Lewis Cass, military officer, politician and statesman from Michigan, contemporaries who were both Freemasons and unsuccessful candidates for U. S. President.; John Gorrie for Florida, a physician and inventor of mechanical refrigeration and William King for Maine, a merchant and Maine’s first governor, both Freemasons; and Dwight D. Eisenhower, Supreme Commander of the Allied Expeditionary Force in Europe during World War II and former President representing the State of Kansas, and Lew Wallace, Union General and former Governor of New Mexico Territory, representing the State of Indiana, both of whom were involved in the entirety of their major wars, and in the events concerning crimes int he aftermath of their wars.

First, Francis Preston Blair, Jr.

He was a U. S. Senator and Congressman for Missouri, and a Union Major General during the Civil War.

Blair was born in Lexington, Kentucky, in February of 1821.

He was the youngest son of politician and newspaper editor Francis Preston Blair, Sr, an early member of the Democrat Party and strong supporter of Andrew Jackson, helping him win Kentucky in the Presidential election of 1828…

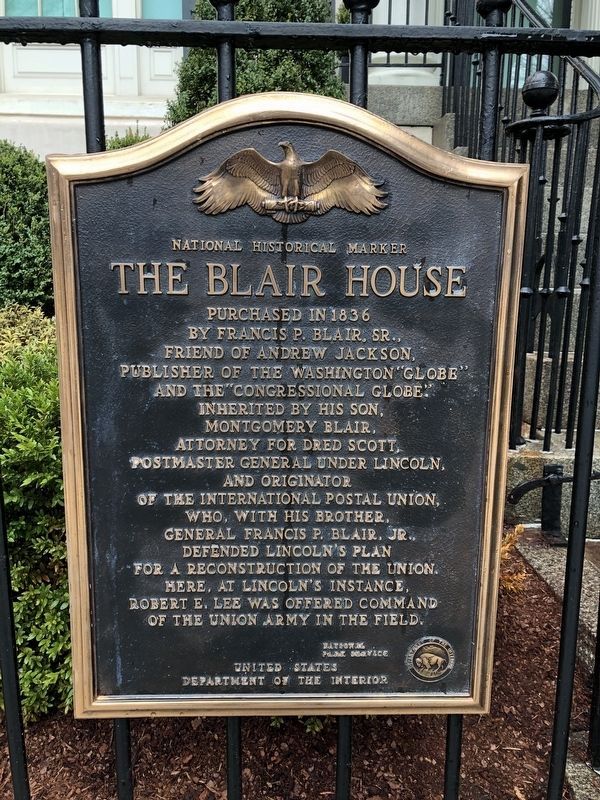

…and his brother Montgomery was the Mayor of St. Louis, and Postmaster General under President Lincoln.

Montgomery Blair was also the attorney for Dred Scott.

The Blair House in Washington, DC, is used an official residence, used primarily as a state guest house for visiting dignitaries and other guests of the U. S. President.

Come to think of it there is a high school in Montgomery County, Maryland, where I grew up, and come to find out, it was named in Montgomery Blair’s honor.

Interesting to note the mascot for the school is called “The Blazer,” and not the “Red Devil” that it looks like.

Hmmm, in the past I wouldn’t have thought twice about this not being noteworthy, but now I look at things completely differently as to what it could possibly mean.

Back to Francis Preston Blair Jr.

He received his early education in schools in Washington, DC, then received his higher education at Yale University in New Haven, Connecticut…

…the University of North Carolina in Chapel Hill…

…and he graduated from Princeton University in New Jersey in 1841.

Blair studied law at Transylvania University in Lexington, Kentucky.

Blair was admitted to the bar in Lexington, and first went into law practice in 1842 with his brother Montgomery in St. Louis, and then went to work in the law office of Thomas Hart Benton in St. Louis, between 1842 and 1845.

Blair travelled out west for a buffalo hunt in 1845, and stayed at Bent’s Fort in present-day La Junta on the Santa Fe Trail in eastern Colorado with his cousin, George Bent.

Bent’s Fort was situated in the vicinity of bends in the Arkansas River, in the same manner that Fort Snelling, which we are told was established in Minnesota in 1819, just happens to be situated directly next to the river-bends of the Mississippi River between Minneapolis and St. Paul, and yes I do think there is an energy connection between star forts and river-bends like these.

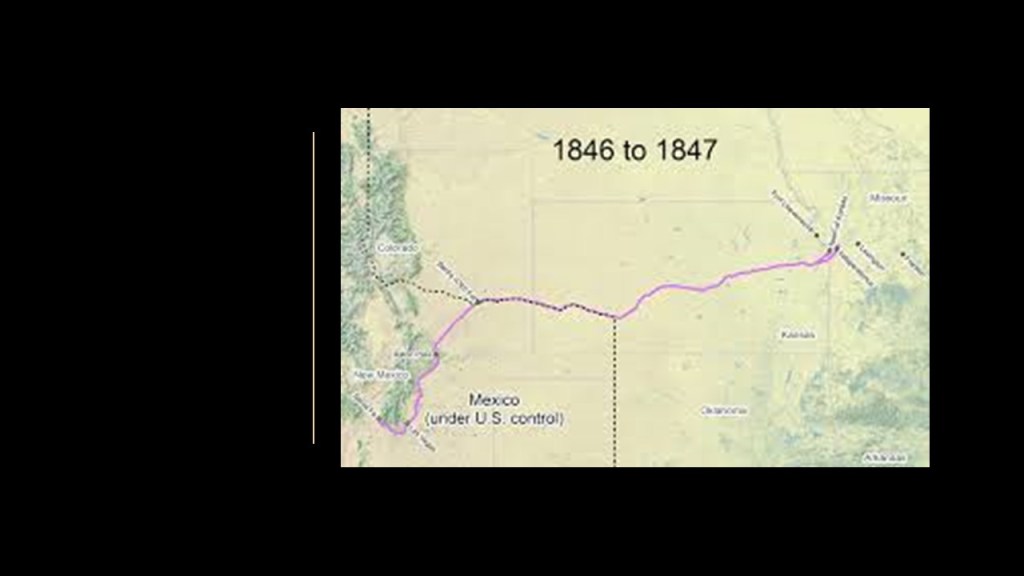

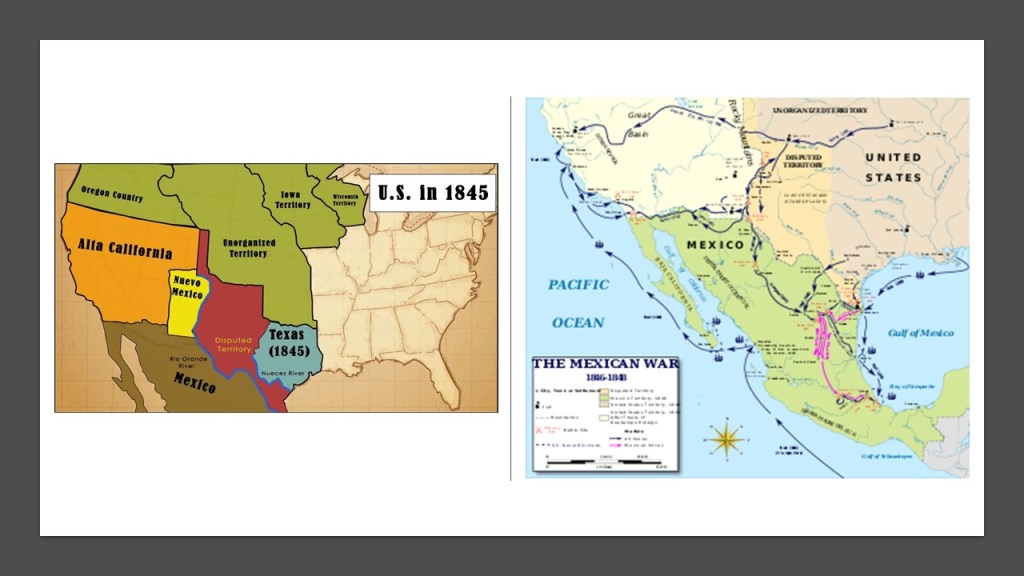

Blair joined the expedition of Brigadier General Stephen Kearney in Santa Fe after the beginning of the Mexican-American War in April of 1846, which started after the United States annexed Texas in 1845.

Kearney took a force, called the “Army of the West,” consisting of about 2,500 men to Santa Fe, New Mexico, during the Mexican-American War, that was headquartered at Fort Leavenworth, Kansas, the oldest settlement in Kansas, and the second-oldest active army post west of Washington, DC.

After the Mexican-American War, broken up into both the “Department of the Pacific” and the “Department of the West,” both commands of the U. S. Army during the 19th-century.

By the end of June of 1846, Kearney’s “Army of the West” advanced on the Santa Fe Trail.

Kearney and his army moved into present-day New Mexico and seized Santa Fe between August 8th and August 14th of 1846, where he established a military government.

Kearney subsequently appointed Francis P. Blair, Jr, as Attorney-General for the New Mexico Territory, and Blair established an American Code of Law for the region, as well as becoming a judge on a newly-established circuit court.

On September 25th of 1846, Kearney set out from Santa Fe with military forces as part of a concerted military operation involving several units to conquer and take possession of California.

After putting up fierce resistance in a number of battles that took place during this time, the Californians surrendered on January 13th of 1847 to John C. Fremont, and Kearney was the military governor of California in Monterey until May of that year.

Blair returned to St. Louis in the summer of 1847.

He entered the political arena, and served in the Missouri House of Representatives from 1852 to 1856, and was an outspoken “Free Soiler,” a coalition party focused on the issue of opposing the expansion of slavery into the western states.

The Free Soil Party was active from 1848 to 1854, at which time it merged into the Republican Party.

Blair was elected to the U. S. House of Representatives as a Republican in 1856.

Though a slave-owner himself, Blair made major speeches during this time calling slavery as a national problem, proposing to solve it by gradual emancipation, and by acquiring land in Central and South America on which to settle freed slaves.

Over the next few years Blair was in-and-out of the U. S. House of Representatives for a variety of reasons and did not stay put there, including becoming a colonel in the Union Army in July of 1861 after being elected in 1860.

We are told the State of Missouri was a hotly-contested border state during the Civil War years, with a mix of pro-Union and pro-secession.

Missouri sent armies, generals and supplies to both sides, maintained two governments, and went through a bloody neighbor-against-neighbor in-state war within the larger national war.

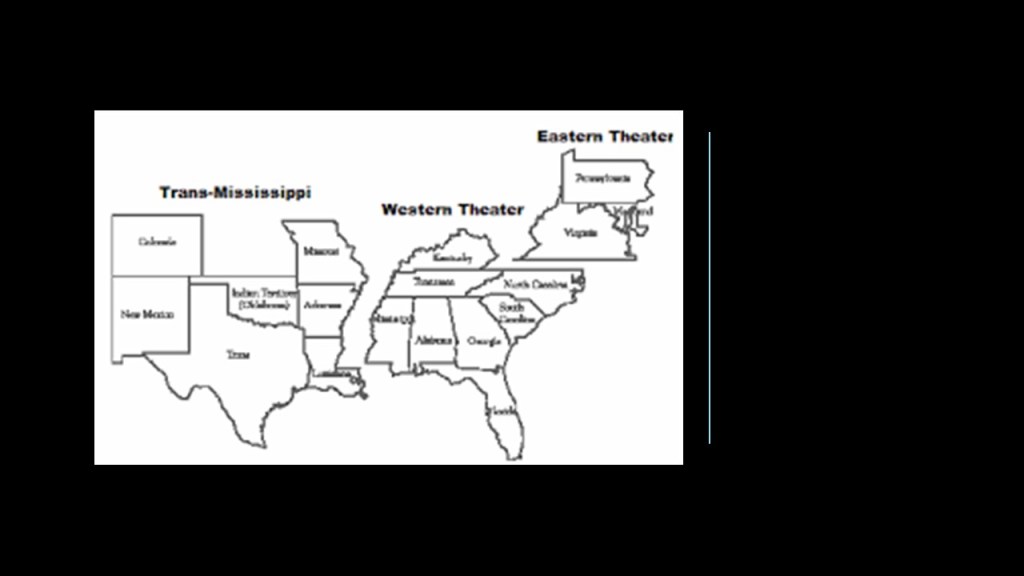

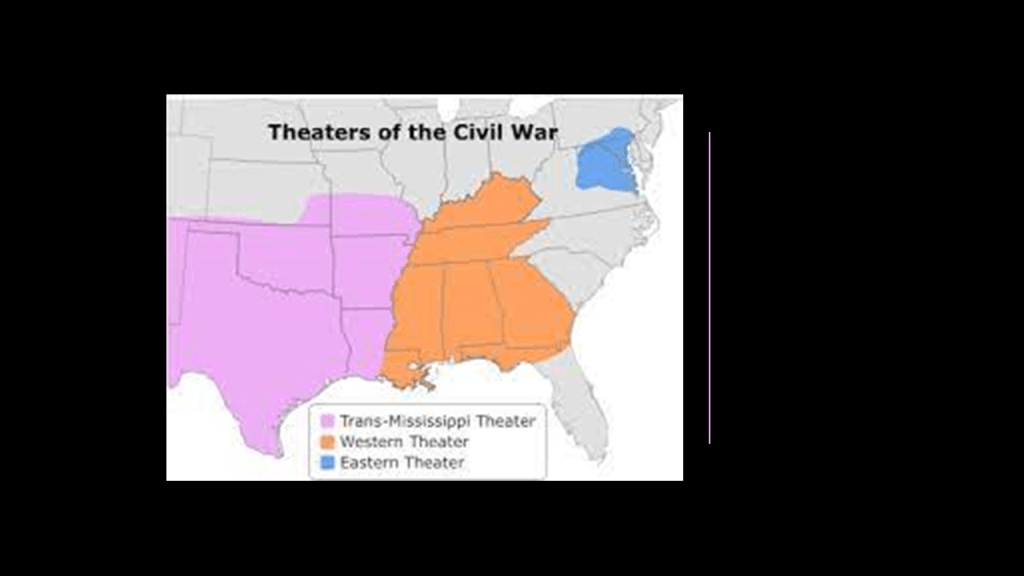

Missouri’s position at the geographic center of the country and at the edge of the American frontier made it divisive battleground, and when the American Civil War started in 1861, the state became a strategic territory in the Trans-Mississippi Theater, with both sides vying for control of the Mississippi River, and the importance of St. Louis as economic hub.

And…apparently Francis P. Blair Jr was in the thick of it in Missouri.

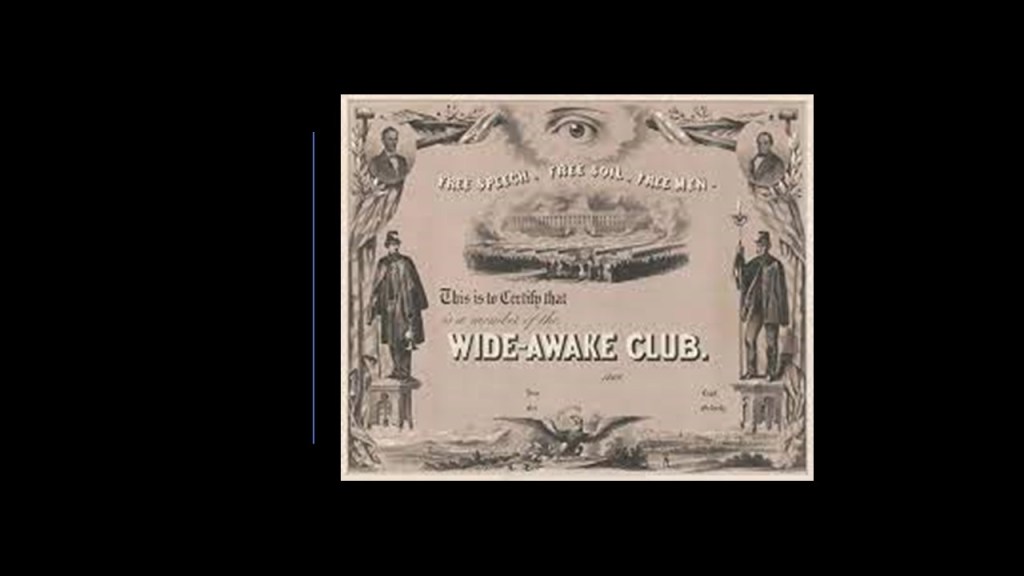

So, for example, right after South Carolina seceded from the Union in December of 1860, Blair anticipated southern leaders trying to lead Missouri into the secession movement, so he personally organized and equipped a Home Guard of several thousand members from a group called the “Wide Awakes,” a paramilitary youth organization cultivated by the Republican Party during the 1860 election year.

By the middle of the 1860 election campaign, Republicans estimated there were “Wide Awake” Chapters in every northern (free) state, and that there were 500,000 members by President Lincoln’s election.

The groups held social events, promoted comic books, and introduced many young people to political participation.

The standard “Wide Awake” uniform was a full robe or cape; a black-glazed cap; and a torch that was six-feet in length, with a whale-oil container mounted to it.

The “Wide Awakes” also adopted a large eyeball as their standard bearer.

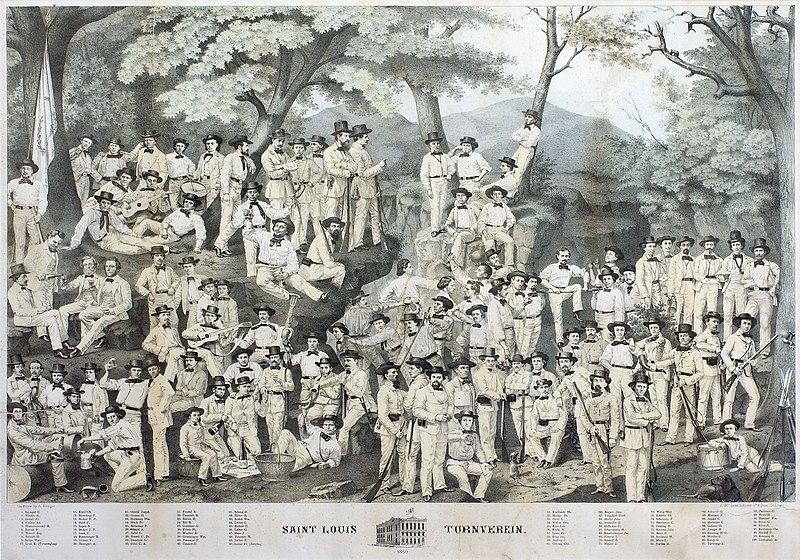

Blair also recruited members of the German gymnastic movement in St. Louis for his Missouri Home Guard.

Called “Turners,” they were members of German-American gymnastic clubs called “Turnvereins.”

They promoted German culture, physical culture, and liberal politics.

The Turner Movement in Germany was started was started by nationalist Friedrich Ludwig Jahn in 1811 when Germany was occupied by Napoleon.

The politically-liberal Turner Movement in Germany was suppressed after the Revolutions of 1848, in which many Turners took part, so many Turners left Germany for the United States, in particular the Ohio Valley Region, Missouri, Wisconsin, and Texas.

Several of these “Forty-Eighters” went on to become Union soldiers and Republican politicians.

Turners were also active in public education and labor movements.

All I can say is “What is this?”

What was really going on here?

So anyway, Blair, and Captain Nathaniel Lyon transferred the arms in the U. S. Arsenal in St. Louis to Alton, Illinois, located across the Mississippi River from St. Louis.

Then, on May 10th of 1861, Lyon, Blair’s Home Guard, and a U. S. Army Company, captured hundreds of secessionist state militia at Camp Jackson who had been positioned to take over the arsenal in an event known as the Camp Jackson Affair…or the Camp Jackson Massacre.

The Massacre took place when the captives were marched into town, and hostile secessionist crowds gathered. From a single gunshot, described as accidental, Lyon’s men fired into the crowd, killing 28 civilians and injuring dozens more.

Several days of rioting followed, which was only stopped with the imposition of martial law.

While Lyon’s actions gave the Union control of St. Louis and the rest of Missouri for the remainder of the Civil War, it deepened the ideological divisions in the state.

After this incident, open warfare between Union troops and followers of the pro-Southern Governor of Missouri, Claiborne Jackson, was about to break-out.

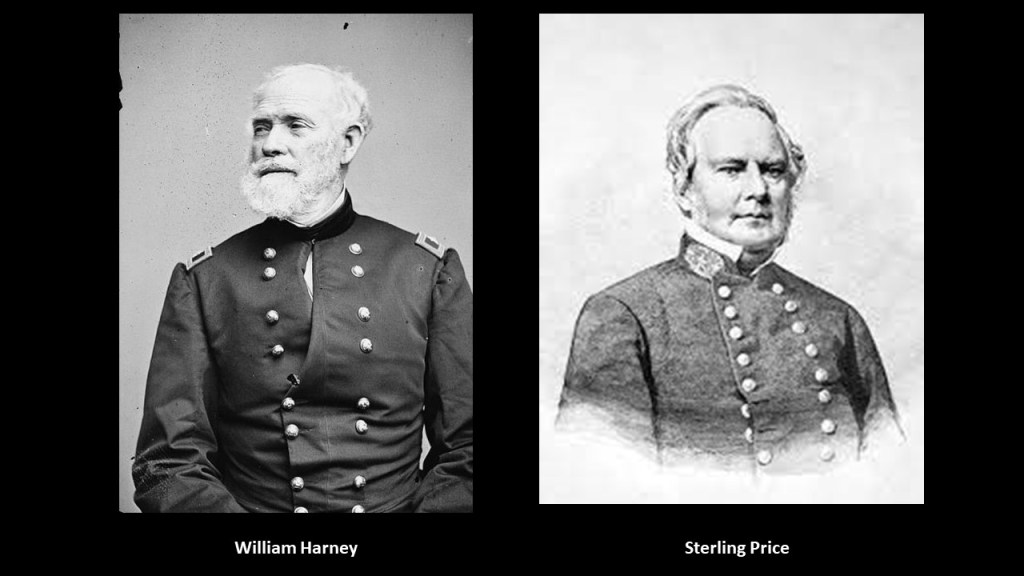

On May 21st, the Union General William S. Harney, Commander of the U. S. Army of the West, agreed to the Price-Harney Agreement with the Missouri State Guard Commander Sterling Price to avoid hostilities.

The Agreement left the Union in control of the arsenal and St. Louis, and left the secessionist, Price, in charge of the Missouri State Guard and most of the rest of the state.

Blair objected to the Harney-Price Agreement, and contacted Republican leaders in Washington, DC.

President Lincoln relieved Harney of command, and Nathaniel Lyon became the Commander of the Department of the West on May 30th of 1861, with an order to keep Missouri in the Union.

Lyon drove Sterling Price and Governor Jackson to the southwestern corner of the state, where Lyon was killed near Springfield, Missouri, in the “Battle of Wilson’s Creek,” the first major battle of the Trans-Mississippi Theater of the American Civil War, and resulted in a Confederate victory.

Though the state stayed in the Union for the remainder of the war, the battle gave Confederates control of southwestern Missouri.

Blair helped organize a new pro-Union state government and John C. Fremont took over command of the U. S. Army Western Department.

Fremont’s mission was to organize, equip, and lead the Union Army down the Mississippi River, reopen commerce, and cut-off the western part of the Confederacy, and his main goal as the Commander of the Western Army was to protect Cairo, Illinois, at all costs.

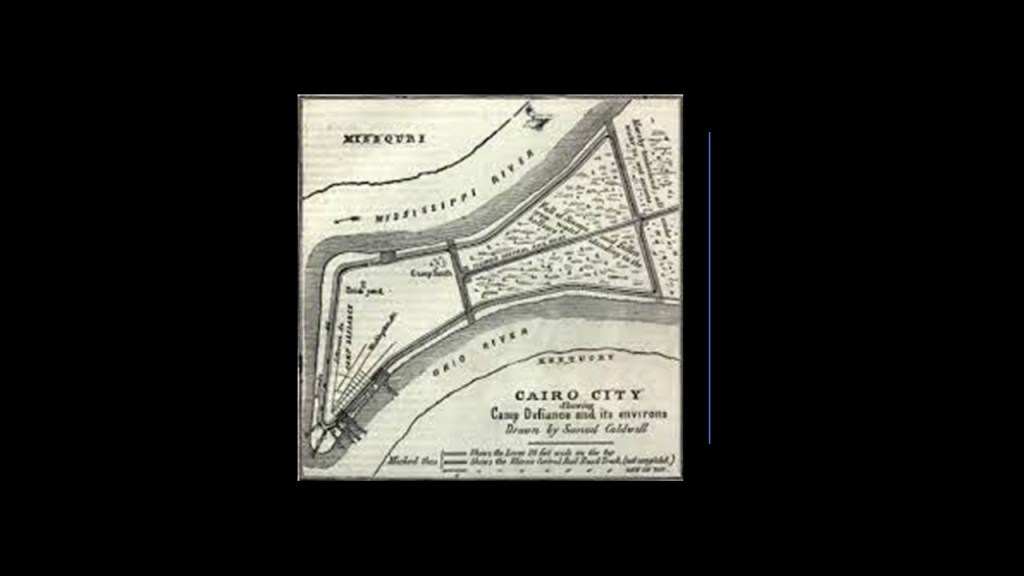

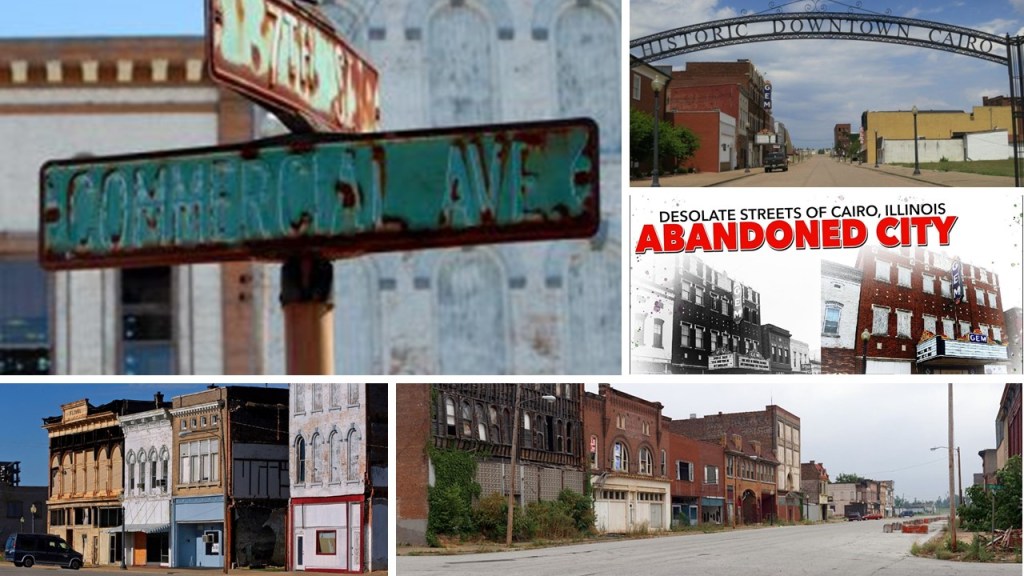

The city of Cairo, Illinois, was located at the southernmost point in Illinois, at the confluence of the Mississippi and Ohio Rivers.

Southern Illinois where Cairo is referred to as “Little Egypt.”

I say was because today, Cairo is empty and deserted, and considered a ghost town.

In its heyday, Cairo was an important city along the steamboat routes and railway lines.

Blair and Fremont, however, clashed over Fremont’s military operations in Missouri, particularly how money was being spent.

Apparently, Fremont was spending money on equipment and supplies, and that Blair expected money to go to his allies in the business community of St. Louis.

Fremont was discredited in part because of Blair’s influence, and replaced as commander in November of 1861.

In July of 1862, Blair was appointed as a colonel of Missouri Volunteers; promoted to Brigadier General of Volunteers in August of 1862; and Major-General in November of 1862.

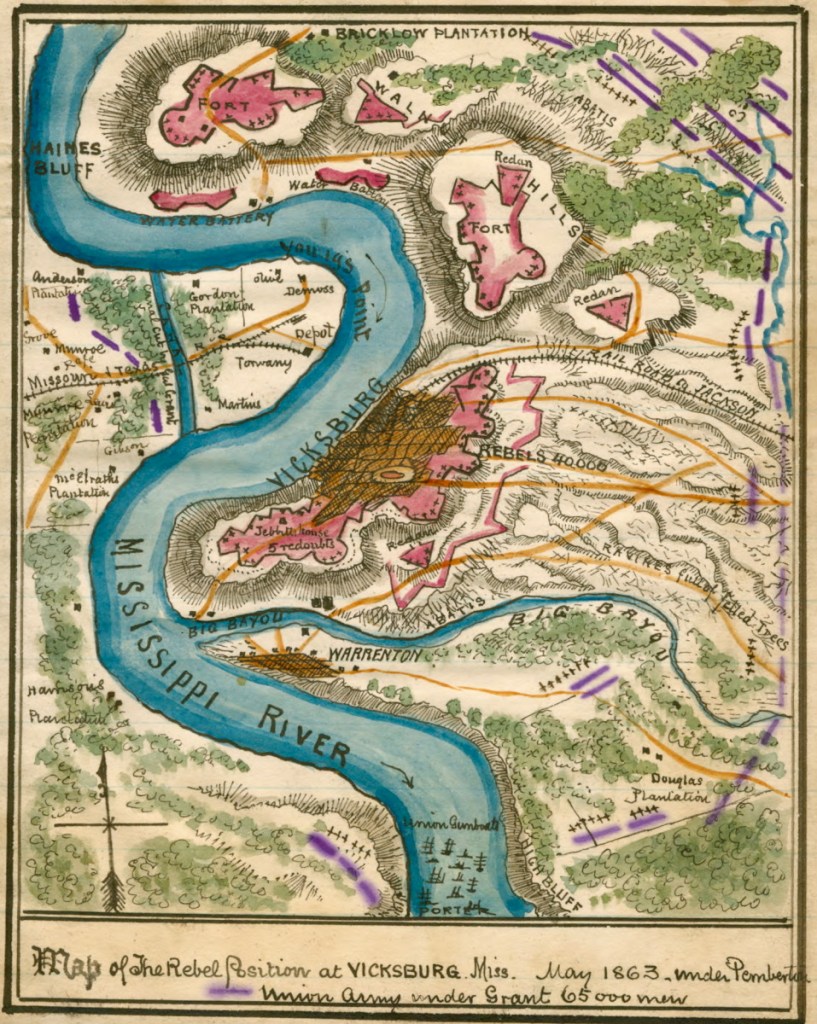

His military service during the Civil War consisted of: commanding a brigade consisting of companies from Missouri, Illinois, and Ohio; commanding divisions in Vicksburg, Chattanooga, and protecting rear armies of Sherman’s “March to the Sea.”

After the Civil War, not only was Blair financially ruined because he spent so much of his private fortune in support of the Union, he also became disgruntled with the Republican Party and left it, along with his father and brother, because the Blair family did not like the Congressional Reconstruction policy.

By this time, for the remainder of Blair’s life, his political career was pretty much over for all intents and purposes.

He died on July 8th of 1875 from head injuries he sustained after a fall at the age of 54, while serving as Missouri’s State Superintendent of Insurance, and was buried at Bellefontaine Cemetery in St. Louis.

Next, I am going to feature Edmund Kirby Smith, who represents the State of Florida in the National Statuary Hall.

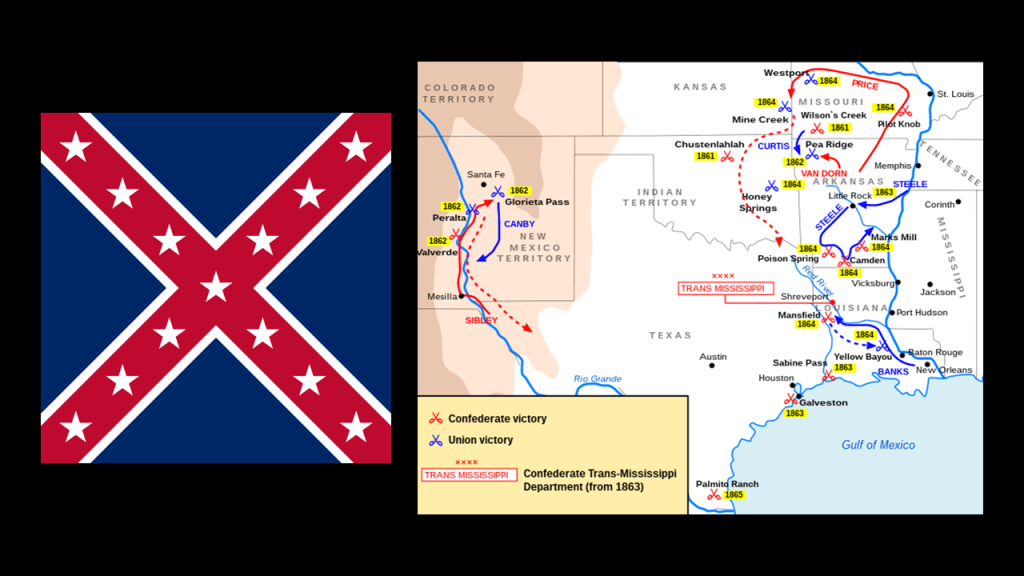

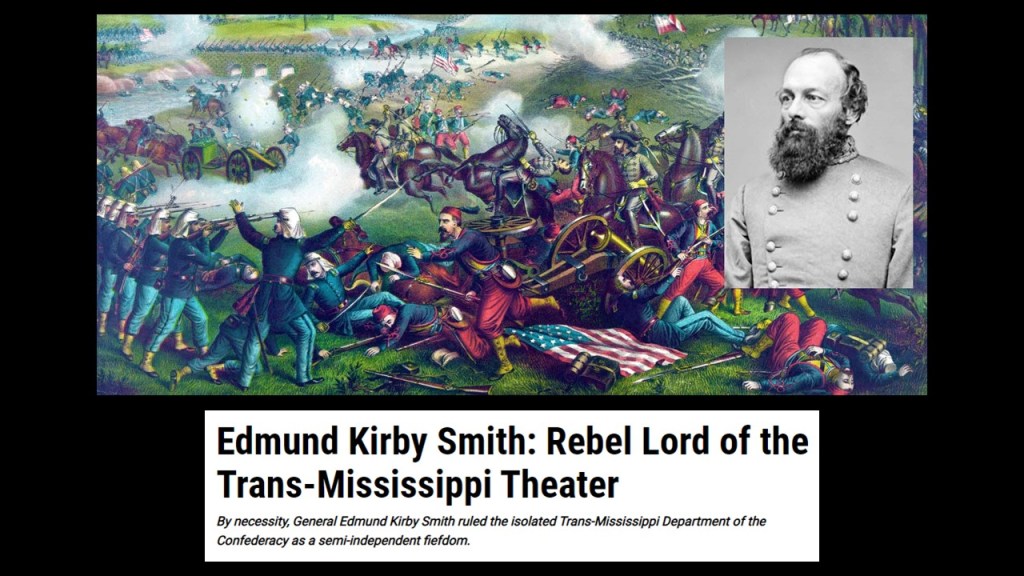

Edmund Kirby Smith was a senior officer of the Confederate States Army who commanded its Trans-Mississippi Department between 1863 and 1865.

The Trans-Mississippi Department of the Confederate States Army was comprised of Arkansas, Texas, Missouri, western Louisiania, Arizona Territory and Indian Territory.

Edmund Kirby Smith was born in St. Augustine, Florida, in 1834, the youngest child of attorney Joseph Lee and his wife Francis.

Both of his parents were natives of Litchfield, Connecticut before moving to St. Augustine in 1821, where his father was appointed as a Superior Court Judge in the new Florida Territory, of which St. Augustine was the capital between 1822 and 1824.

Litchfield, Connecticut was the location of the Litchfield Law School, the first independent law school established in America for reading law, founded by lawyer, educator and judge Tapping Reeve in the 1770s, and it was a proprietary school that was unaffiliated with any college or university.

I looked up meanings for the unusual name of “Tapping Reeve,” and here is what I found as some possibilities:

Tapping – To exploit or draw a supply from a resource.

Reeve – Administrator, attendant; curator; agent; director; foreman; and the list goes on.

Something to think about.

Edmund Kirby Smith entered West Point in 1841 and graduated in 1845, and by August of 1846 was serving in the 7th U. S. Infantry as a Second Lieutenant.

He served in several battles of the Mexican-American War, which took place between 1846 and 1848 after the United States annexed Texas in 1845, and had obtained the rank of captain by the end of it.

After the Mexican-American War and before the American Civil War, Smith taught mathematics at West Point between 1849 and 1852, as well as pursuing his scientific interest in botany, and was credited with collecting and describing species of plants native to Florida and Tennessee.

Then, he returned to leading troops in 1859 in the Southwest.

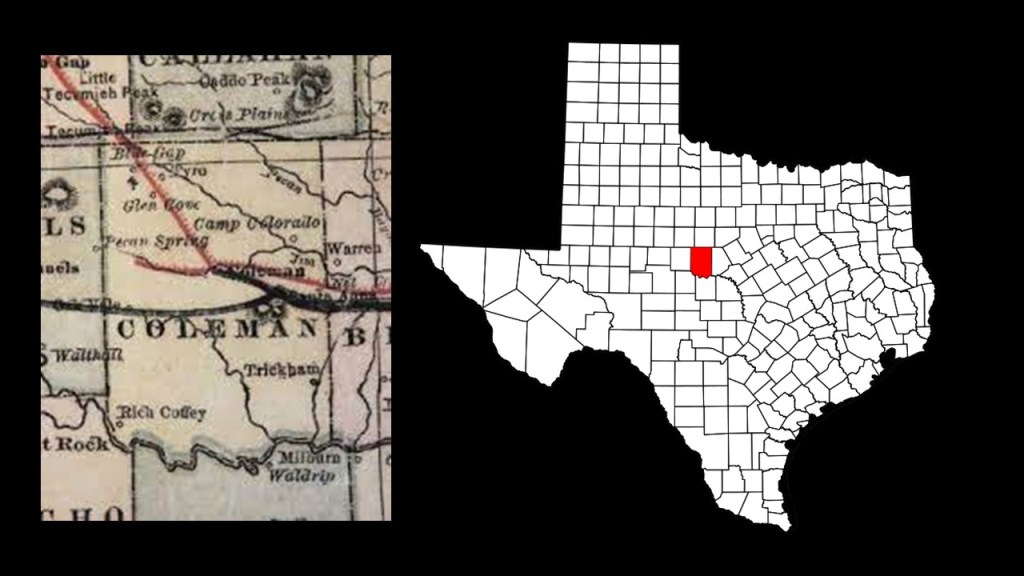

Smith was promoted to Major in January of 1861 when Texas seceded from the Union, and he refused to surrender his command at Camp Colorado in what is now Coleman to the Texas State Troops.

Within just a few months, Smith had resigned his commission in the United States Army to join the Confederacy.

He had been promoted to the rank of Brigadier-General in June of 1861, and given a command of a brigade in the Army of the Shenandoah, which he led in the First Battle of Bull Run on July 21st of 1861, the first major battle of the civil war, in which he was severely wounded.

Smith recovered from his injuries, and returned to duty in October of 1861 as a Major-General and division commander of the Army of Northern Virginia for awhile, the primary military force of the Confederate States in the Eastern Theater of the Civil War.

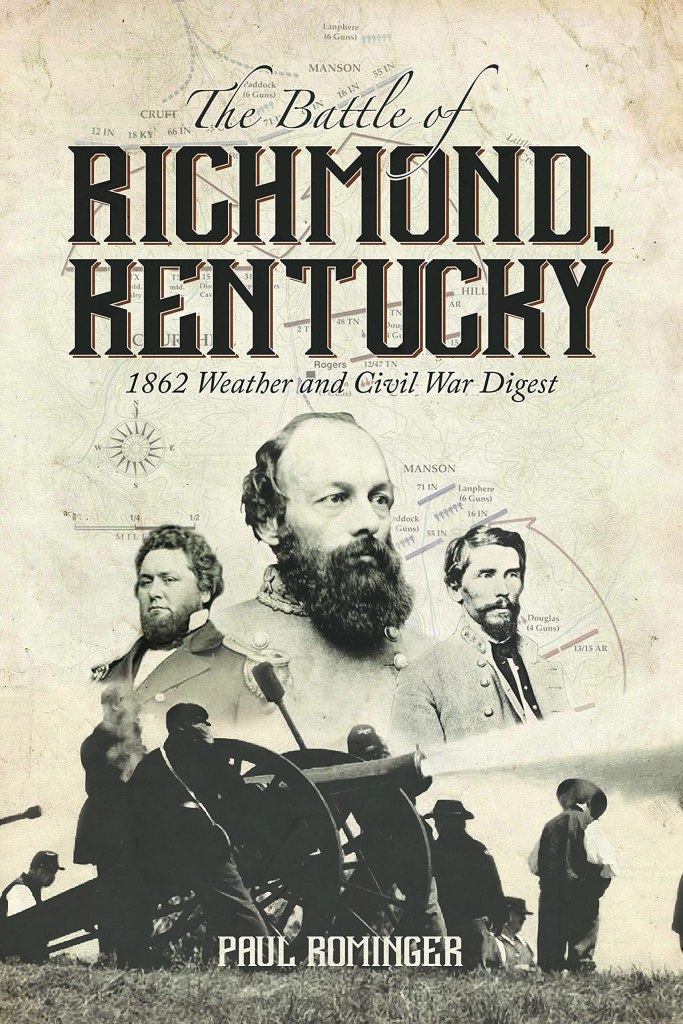

Then in February of 1862, he was sent west to command the eastern division of the Army of Mississippi, cooperating with General Braxton Bragg in what was called the “Invasion of Kentucky,” during which time he was victorious in the Battle of Richmond in Kentucky, called one of the most complete confederate victories in the war, and the first major battle in the Kentucky Campaign.

By October of 1862, Smith was promoted to Lieutenant-General, commanding the 3rd Corps, Army of Tennessee.

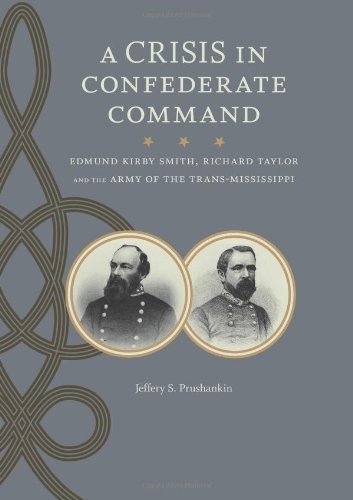

Then in January of 1863, Edmund Kirby Smith was transferred to command the Trans-Mississippi Department, and for the rest of the Civil War he remained west of the Mississippi River.

His Trans-Mississippi Department never had more than 30,000 men stationed over a large area and he wasn’t able to concentrate his forces enough to challenge the Union Army or Navy.

After the Union forces captured Vicksburg, Mississippi on July 4th of 1863…

…and Port Hudson in Louisiana, on July 9th of 1863…

…Edmund Kirby Smith’s forces were cut off from the Confederate Capital of Richmond, Virginia.

As a result of being cut-off from Richmond, Smith commanded and administered a nearly independent area of the Confederacy, and the whole region became known as “Kirby Smithdom.”

Ultimately, the Confederate General Edmund Kirby Smith surrendered the Trans-Mississippi Department on May 26th of 1865 on board the U. S. S. Fort Jackson on Galveston Bay in Texas to the Union Major General Edward Canby, approximately eight-weeks after General Robert E. Lee’s surrender to General Ulysses S. Grant in Virginia.

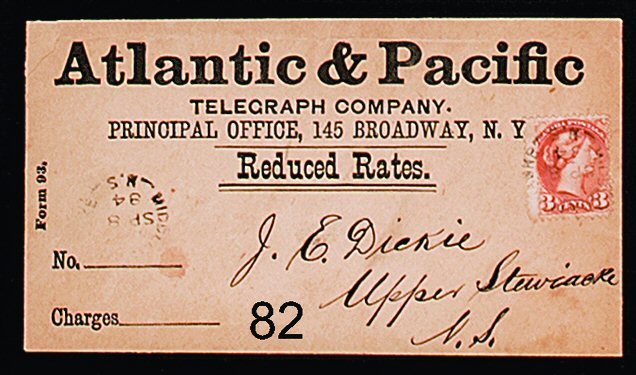

Edmund Kirby Smith was active in the telegraph business as the President of the Atlantic and Pacific Telegraph Company following the Civil War, from 1866 to 1868…

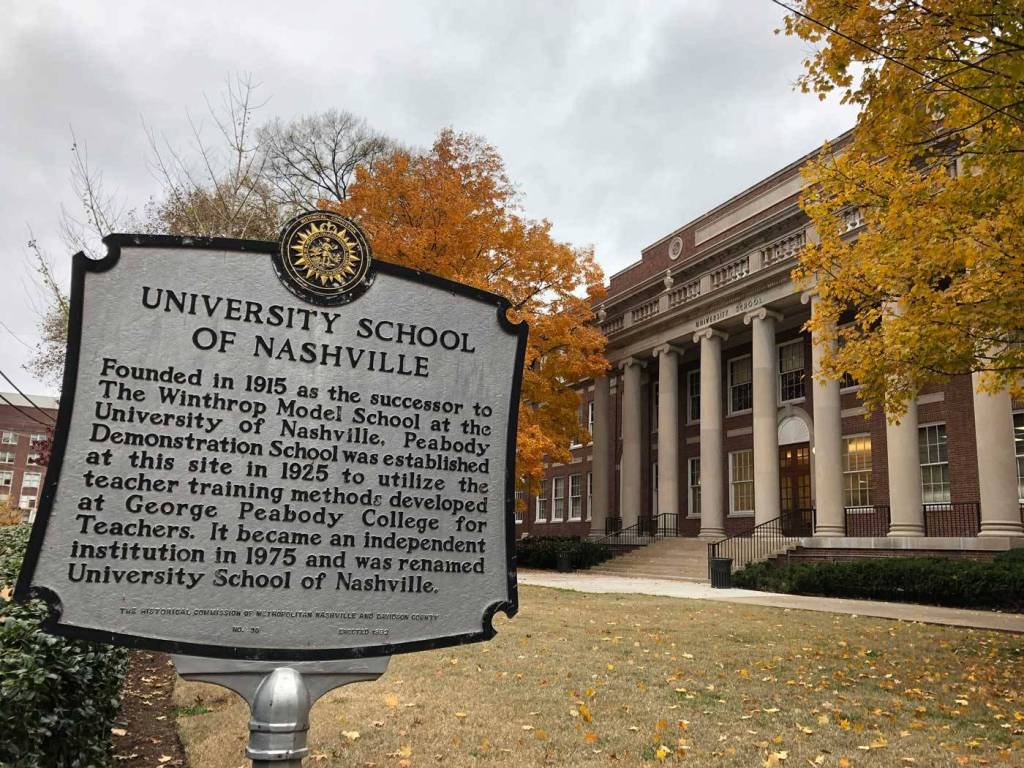

…served as the Chancellor of the University of Nashville from 1870 and 1875…

…and taught mathematics and botany at the University of the South in Sewanee, Tennessee…

…in whose cemetery he was buried after his death from pneumonia in 1893.

I am bringing forward unlikely pairs of historical figures who are represented in the National Statuary Hall who have things in common with each other, as mentioned at the beginning of this post.

In this pairing for things in common with each other, both men were out in what became the western United States, after Texas was annexed in 1845, and heavily involved in the events and activities of the Mexican-American War, which lasted from 1846 to 1848.

Both Blair and Kirby Smith served as General-grade officers during the Civil War, with Blair commanding Union troops, and Kirby Smith commanding Confederate troops.

And both men were closely connected with the Trans-Mississippi Department, with Blair’s home state of Missouri being part of it, and from July of 1863 to May of 1865, Kirby Smith was the commander and administrator of this pretty much independent area of the Confederacy.

Shreveport in Louisiana was the location of one of the two headquarters of the Trans-Mississippi Department of the Confederate Army, the other being in Marshall, Texas.

I first learned about the Trans-Mississippi Department when I was doing some research around Albert Pike, an influential 33rd-degree freemason who was a senior officer of the Confederate Army who commanded the District of Indian Territory in the Trans-Mississippi Theater of the American Civil War, otherwise known as Oklahoma.

Around this same time period, Albert Pike was the Sovereign Grand Commander of the Supreme Council of Scottish Rite’s Southern Jurisdiction, a position which he held from 1859 to 1891.

As a matter of fact, there is an interesting similarity between the decoration for the Trans-Mississippi Department, with the motto of the Confederacy – “Deo Vindice” or something along the lines of “With God, our Defender” – and the decoration of the Order of the Sovereign Grand Inspectors General of the Scottish Rite, which has the Masonic Motto of the 33rd-Degree – “Ordo Ab Chao” and “Deus Meumque Jus” – inscribed on it, which translates to “Order out of Chaos” and “God and My Right.”

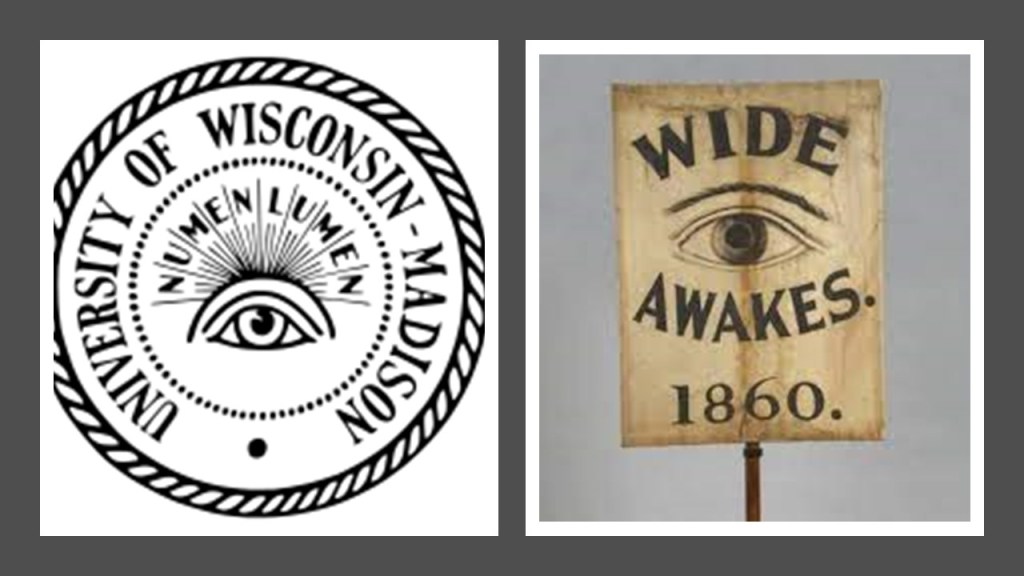

These sound a lot like the motto for the University of Wisconsin-Madison – “Numen Lumen” – which can be translated from the Latin as “God, Our Light,” and like “Heaven’s Light Our Guide” that was found on the flags of the various Presidencies in India, like that of the “Madras Presidency,” of the British East India Company.

And the University of Wisconsin-Madison seal looks like the standard of Blair’s “Wide Awake” movement seen earlier in this post.

At any rate, we are told that over 200,000 men were engaged in the Trans-Mississippi Theater of War, and there were all together 7 battles in Arkansas, New Mexico, Missouri and Louisiana between 1862 and 1864.

This was also the heart of the ancient Washitaw Empire, with Monroe, Louisiana being the Imperial Seat.

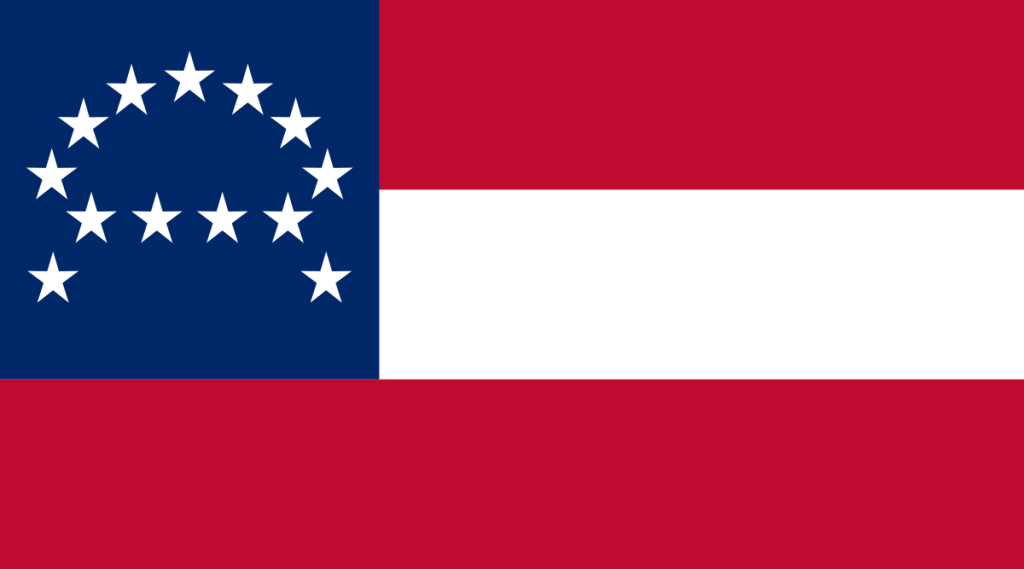

This was the battle flag of the “Army of the West,” another name for the Trans-Mississippi District of the Confederacy’s Army of the Mississippi.

What would stars and a crescent be doing on a Confederate Army’s battle flag?

The star and crescent symbolism has been identified with Islam, and what we are told is that this happened primarily with the emergence of the Ottoman Turks, and for one example of several national flags, are depicted on the modern Turkish flag.

I also read where the Egyptian hieroglyphs of a star and the crescent moon denote the Venus Cycle from morning star to evening star.

And why is theater, defined as a collaborative form of performing art that uses live performers, usually actors or actresses, to present the experience of a real or imagined event before a live audience in a specific place, like a stage, the word choice for an area or place in which important military events occur or are progressing?

A theater can include the entirety of the air space, land and sea area that is or that may potentially become involved in war operations.

As is so often the case, I am left with more questions than answers about the gaps, no…gaping holes, in our historical narrative about what was really going on here during this period of time.

The National Statuary Hall at the U. S. Capitol building consistently provides us with tantalizing clues in the lives of the historical characters chosen to represent their respective states, almost like a “Who’s Who” of the New World Order’s historical reset activities, many of whom are obscure individuals like Francis Preston Blair, Jr, and Edmund Kirby Smith.

Please contact me at your convenience. After reading your section, we have much in common, and I know a lot about who has been keeping me from my real family lineage, but I have no one to help me in my need for answers because my “family” will not and cannot, in fact, help shed light. Primarily on my dad’s side of the family, similar to yours, deep south roots and Belgium/Scotland/France, is the most concise I can be at the moment. Mother’s side is a deception as well and guarded by intelligence community and my “uncle”. Stonewalled by government FOIA’s, family in intelligence, and my lost history entirely before mid 1800. I am also a gifted and licensed psychic, thanks be to the Creator. But in my devotional time I cannot get the answers I need. Thank you so much for all of your work, it’s my path as well, all of this awakening, and I now know it is to share with all who can hear me a warning with a sense of urgency on a more spiritually ordained or Ethereal level.

LikeLike