I am going to be bringing forward research I have done in the past, as well as new research, in this series on the Great Lakes region of North America.

So far I have looked in-depth at cities and places all around the shores of Lake Superior and Lake Michigan, paying particular attention to lighthouses; railroad and streetcar history; waterfalls, wetlands and dunes; interstates and highways; major corporate players; mines and mining; labor relations; and many other things.

I am going to be taking a close look at the Michigan-side of Lake Huron in the third-part of this series, and where I expect to see more of exactly the same kinds of things seen thus far.

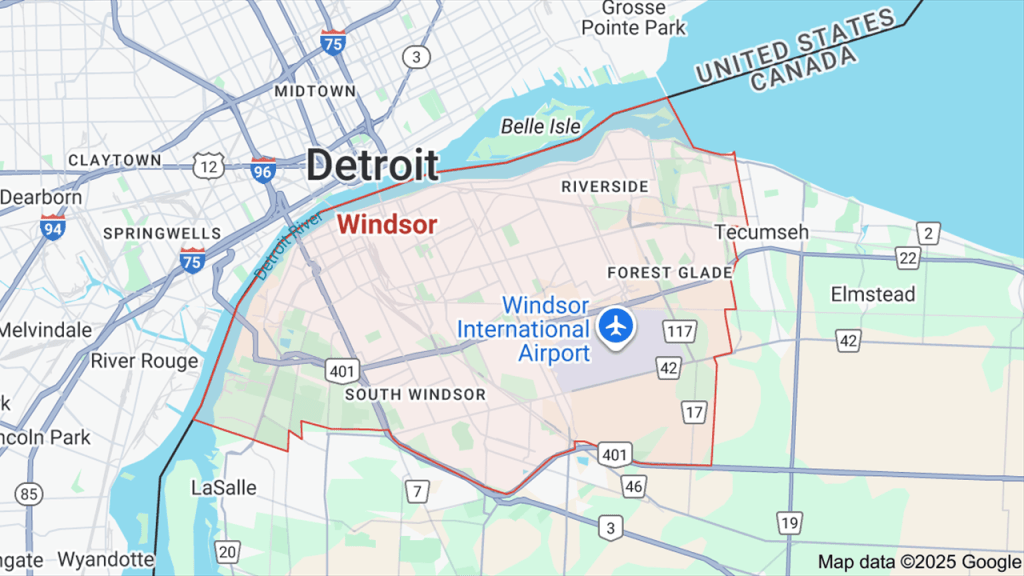

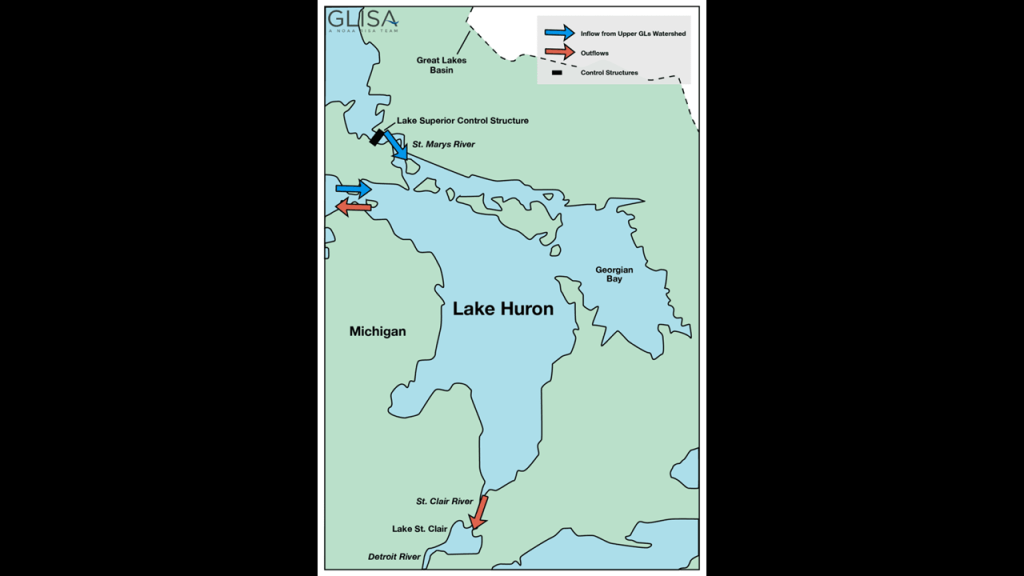

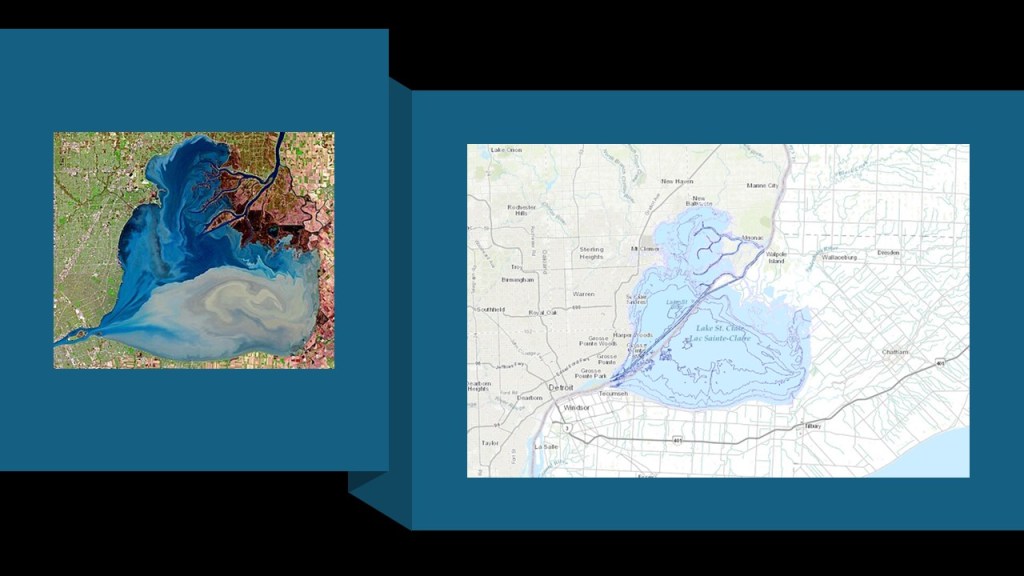

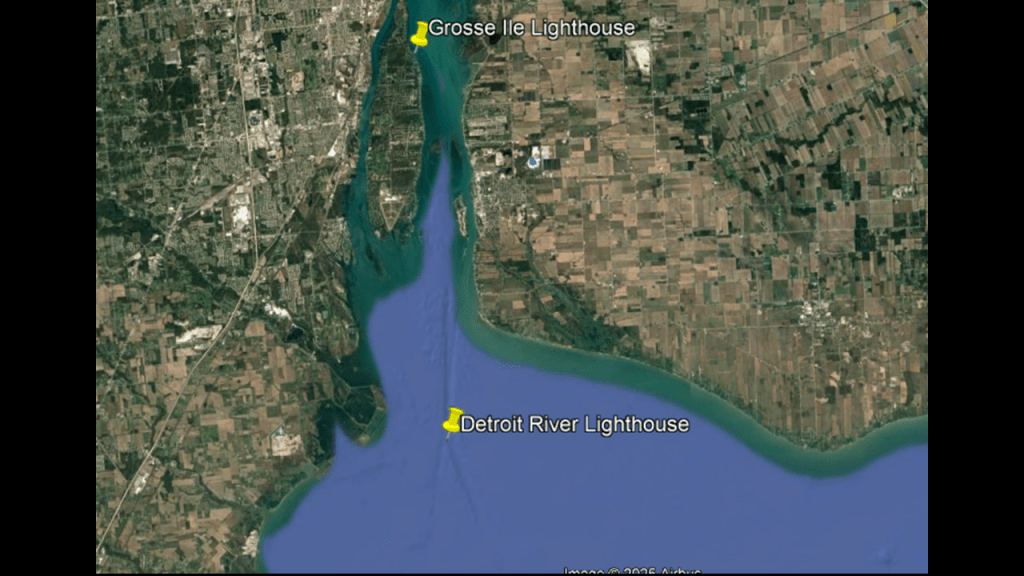

Lake Huron is connected to Lake Michigan by the Straits of Mackinac; to Lake Superior by the St. Mary’s River; and to Lake Erie via the St. Clair River, Lake St. Clair and the Detroit River, where the city of Detroit is located on land situated between Lake Huron and Lake Erie the two lakes.

It is shared on the north and east by the Province of Ontario and to the south and west by the State of Michigan.

We are told that Lake Huron is considered to be hydrologically a single lake with Lake Michigan because the flow of water between the Straits of Mackinac keeps their water levels in overall equilibrium.

Lake Huron has the greatest shoreline length of the Great Lakes, at 3,827-miles, or 6,157-kilometers, including 30,000 islands, and has not experienced heavy industrialization like the other Great Lakes.

Georgian Bay is a large bay of Lake Huron, and sometimes called “the sixth Great Lake” because of it’s size and distinctiveness.

It is 5,792-square-miles, or 15,000-square-kilometers, in size.

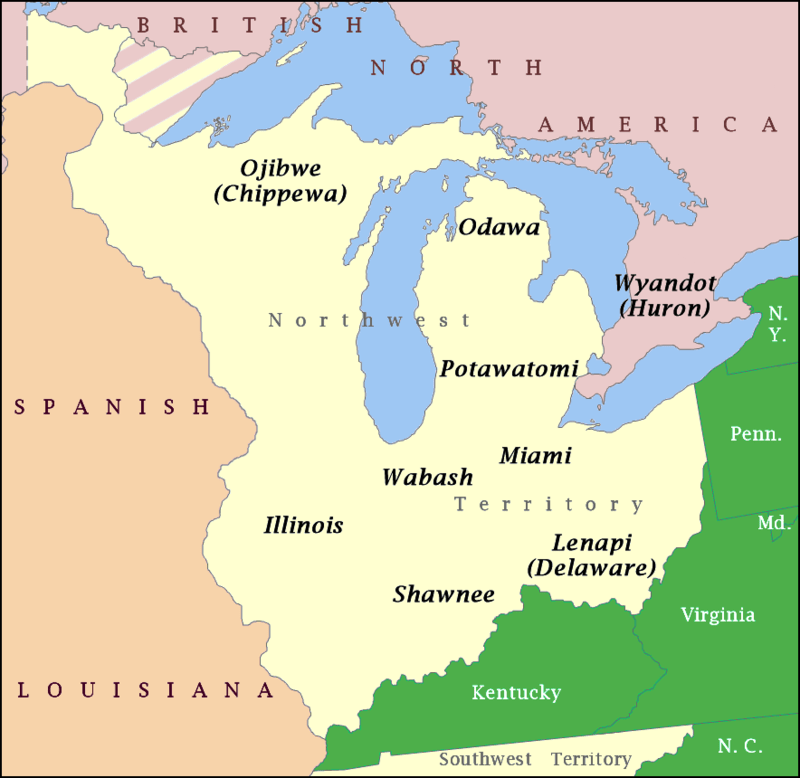

The name of the lake is derived from the indigenous Huron people of the region, also known as the Wyandot.

Their traditional lands extended to Lake Huron’s Georgian Bay and Lake Simcoe in Ontario.

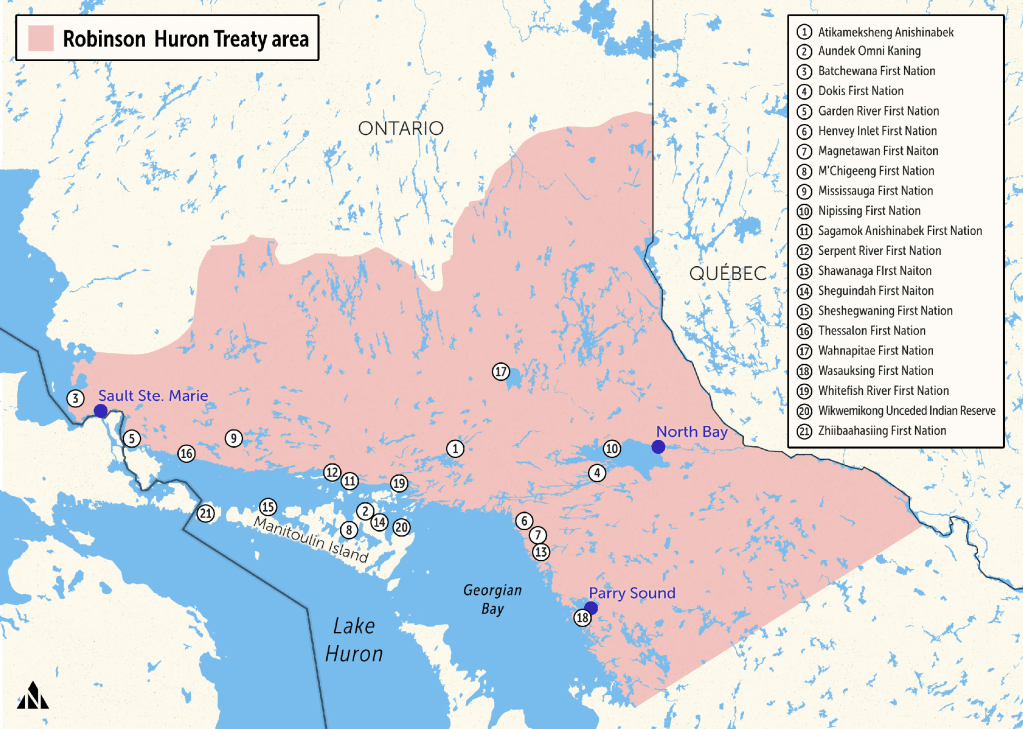

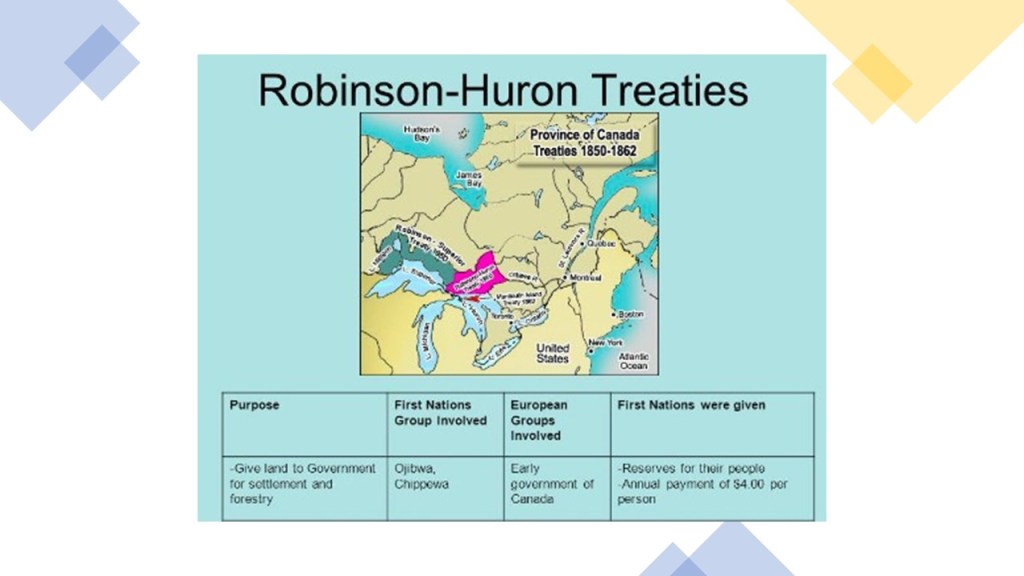

We are told a large tract of Huron land in Canada was signed over to the British Crown in 1850, by the local chiefs, as part of the Robinson-Huron Treaty.

In return, the Crown pledged to pay an annuity to these First Nations people, originally set at $1.60 per treaty member, and it was last increased to $4 in 1874, where it is fixed to this day.

Reservations were also established as a result of this Treaty.

This is what we are told about the Huron or Wyandot people.

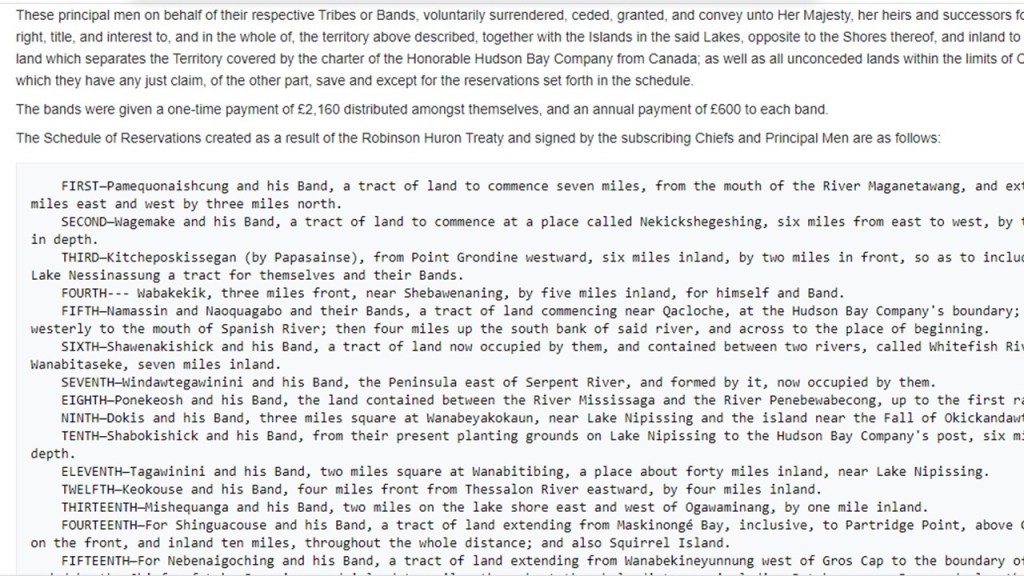

Their language is Iroquoian, with this map reflecting where Iroquoian was spoken.

Almost all of the surviving Iroquoian languages are severely endangered, with some languages only having a few elderly speakers remaining.

The two languages with the most speakers are Mohawk and Cherokee, though spoken by less than 10% of their respective people.

Thus far in the series, I have found that there was a pervasive Jesuit presence all over Lake Superior and Lake Michigan in our historical narrative.

When I was looking for information on the Huron people, I found out that they were mentioned in the chronicles of Jesuit Missions in New France from 1632 to 1673 called “The Jesuit Relations,” which were said to be reports from missionaries in the field to update their superiors on their progress in converting them.

This report was said to be from Gabriel Sagard in 1632 with regards to the country of the Hurons.

Sagard was a French Franciscan lay brother known for being one of the earliest missionaries to New France.

Along with the Jesuits, the Franciscans were quite active in the Great Lakes region early on in our historical narrative.

This passage from 1639 in the “Jesuit Relations” describes the Hurons as robust and tall, and wearing beaver skins, necklaces and bracelets of porcelain, and grease their hair and paint their faces.

It is my conclusion that publications like these and many others I have come across in my research were setting the stage in seeding the new historical narrative into our consciousness by those responsible for the hijack of the original positive civilization that built all of Earth’s infrastructure that the indigenous people were primitive tribal hunter-gatherers instead of being the actual builders of a highly advanced, ancient worldwide civilization.

Since this is not in our historical narrative, we don’t even question what we are told about it being built by other cultures or civilizations.

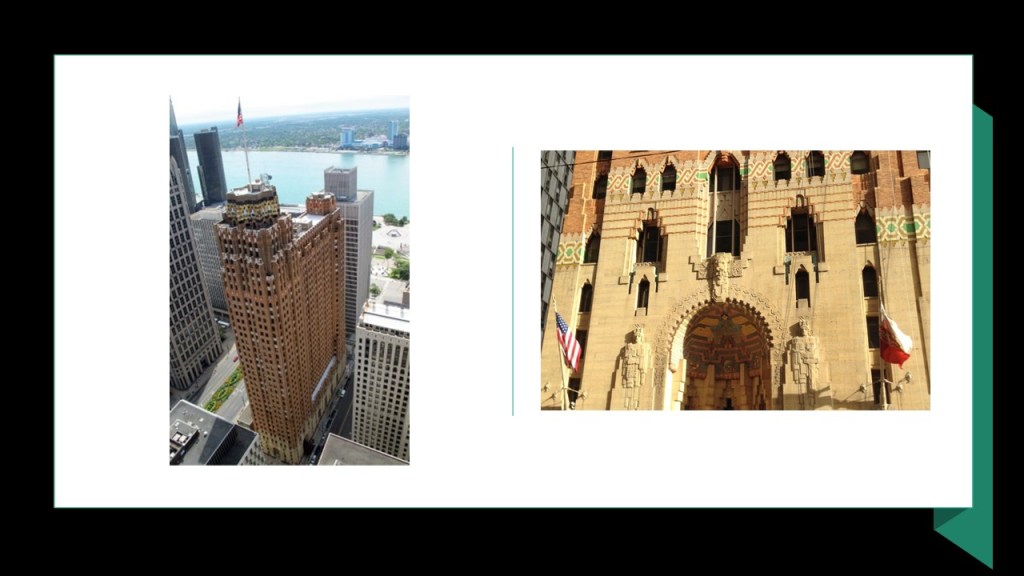

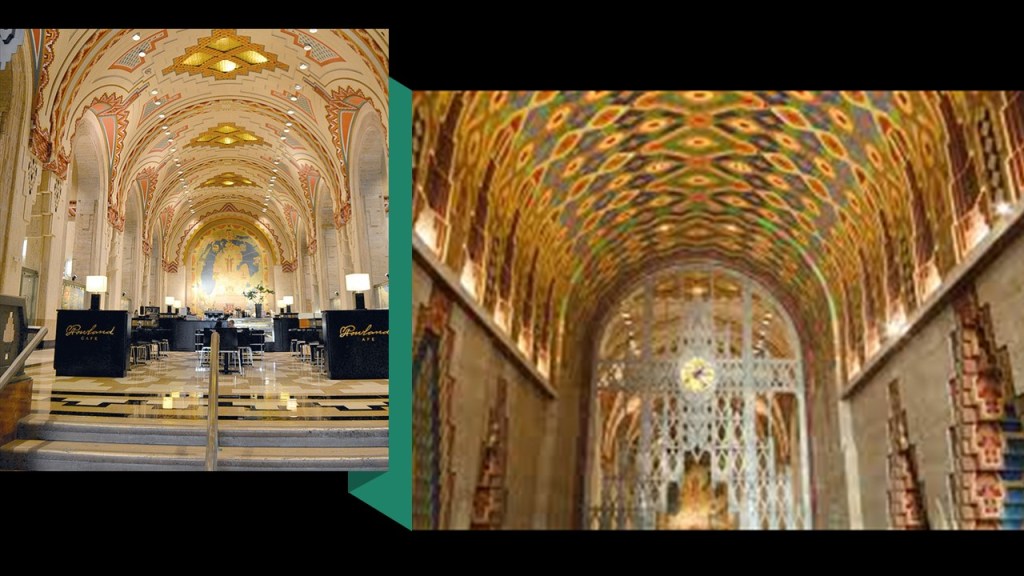

Moorish Masons of the Ancient Ones were the Master Builders of Civilization, and their handiwork is all over the planet, from ancient to modern.

All of their Moorish Science symbolism was taken over by other groups claiming to be them, falsely claiming their works, or piggy-backing on their legacy.

Or given a darker meaning by association with certain things that were not the original meaning.

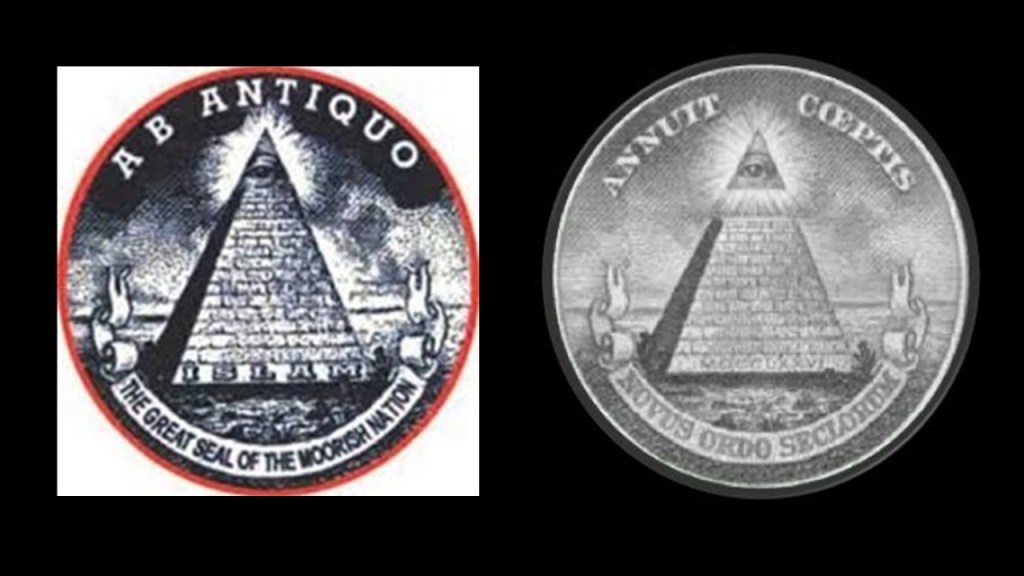

For example, this is the Great Seal of the Moors on the left, compared to the symbol on the back of the U. S. Federal Reserve Note, commonly known as the One-dollar-bill.

You can see that their symbols were co-opted from the original, and have come to have certain negative associations, like associating the pyramid with the eye on top of it with Big Brother, the New World Order, and the Illuminati instead of the Pineal Gland, also known as the third-eye, and our direct connection with Our Creator.

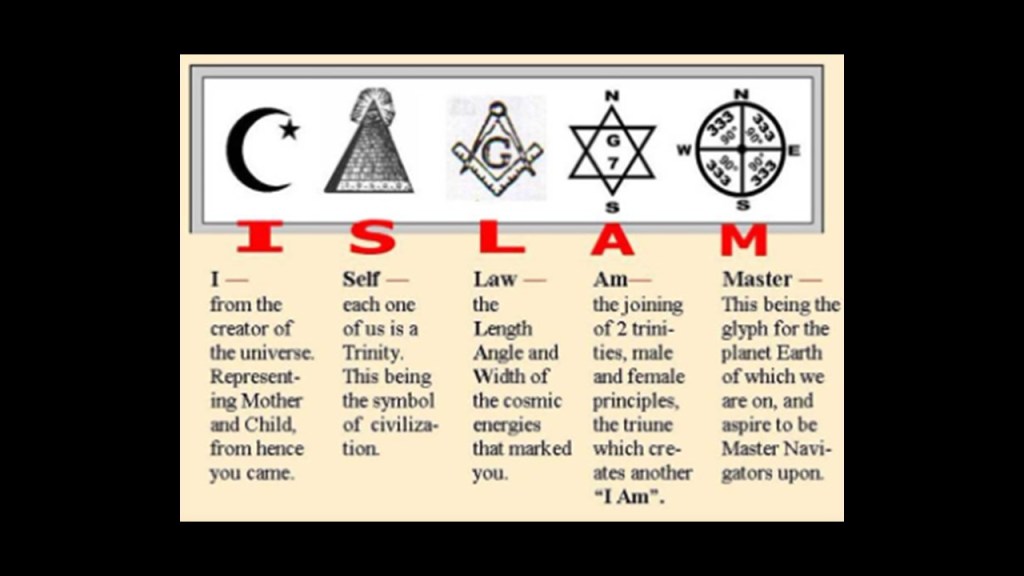

Islam in its original form is about applied Sacred Geometry and Universal Laws, and was nothing like the weaponized form of radical Islam we see today that is playing a divisive and destructive role in the world that is not in accordance with Humanity’s best interests.

I also believe that the Moors and the Tribes of Israel were one and the same, and that this identity was also hijacked as well by those responsible for the hijack of the original positive civilization.

Many years ago, before I started doing my own research in 2018, and when I was learning about these kinds of things, I watched a Megalithomania presentation by Christine Rhone on “Twelve Tribe Nations – Sacred Number and the Golden Age.”

She co-authored a book with John Michel of the same name.

Among other things, they followed the Apollo – St. Michael alignment across countries and continents all the way to Jerusalem in Israel.

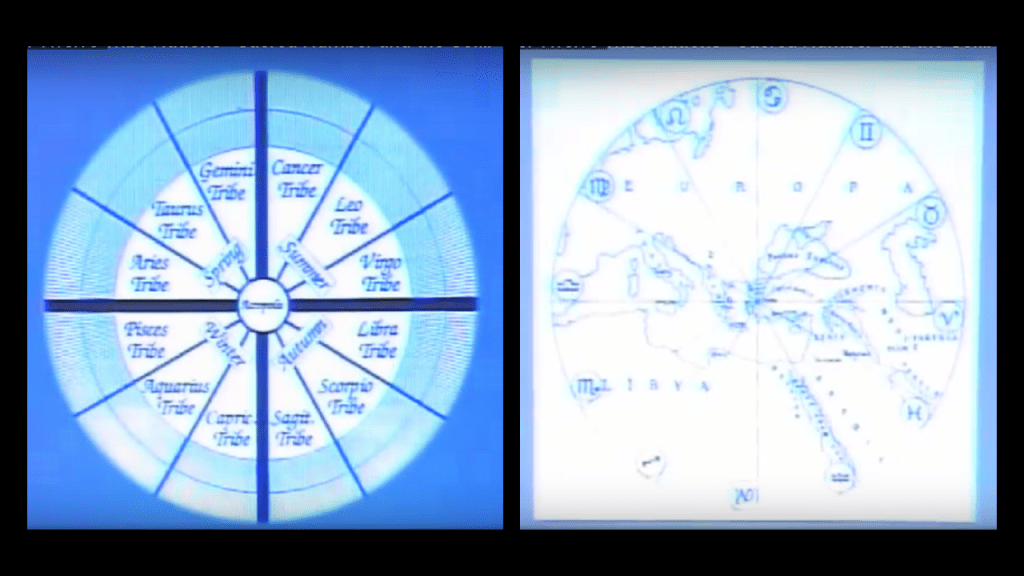

They discuss records and traditions of whole nations being divided into twelve tribes and twelve regions, each corresponding to one of the twelve signs of the zodiac and to one of the twelve months of the year. All formed around a sacred center.

It stands to reason that these people would apply the same concepts of Harmony, Balance, Beauty, Sacred Geometry, and aligning heaven and earth, to building their communities and themselves that they applied to building all of the infrastructure of the Earth.

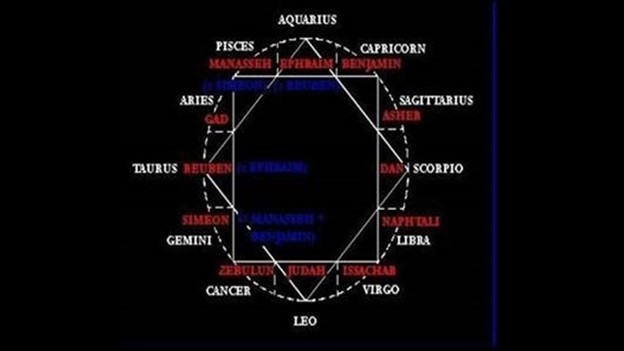

There is an 8-pointed star visible in this graphic of the twelve Tribes of Israel as they correspond to the twelve constellations of the Zodiac.

I have found this same 8-pointed star symbol all over the Earth.

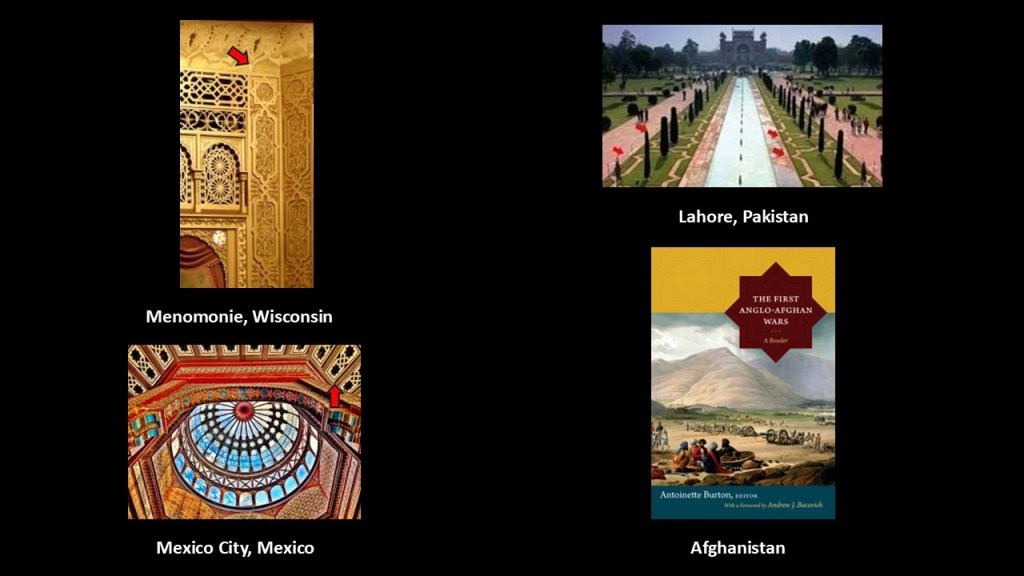

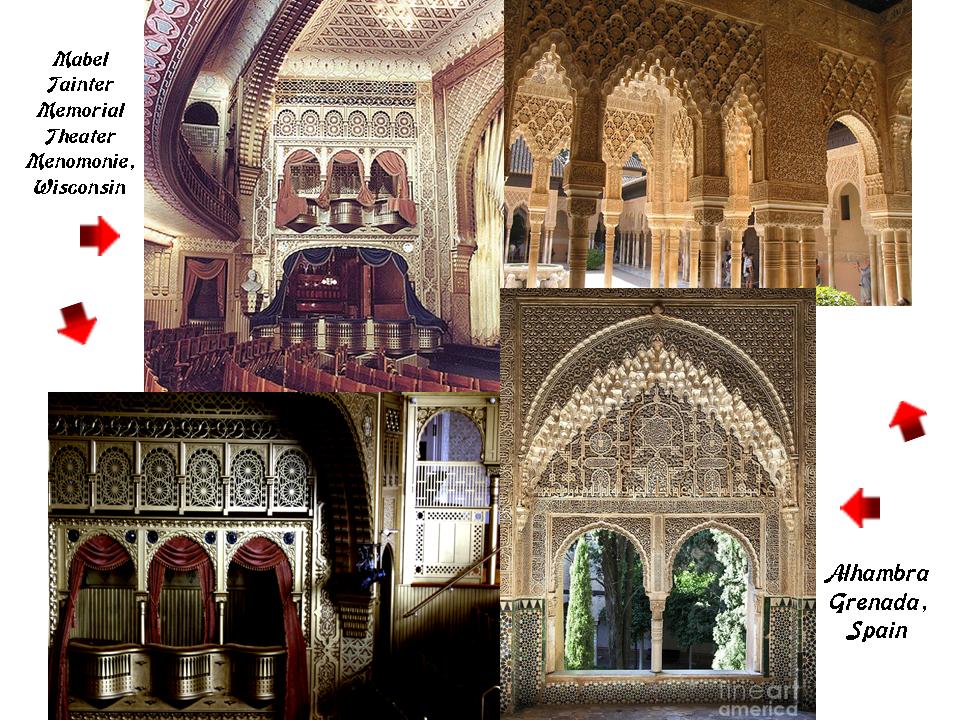

It can be found in the Mabel Tainter Memorial Theater in Menomonie, Wisconsin on the top left; in the Mughal Garden Complex in Lahore Pakistan, on the top right; on the Moorish Kiosk in Mexico City on the bottom left; and on the cover of this book about the First Anglo-Afghan War on the bottom right, among countless examples I have found all over the Earth.

The Mabel Tainter Memorial Theater here in Menomonie, Wisconsin, said to have been built in 1889 in the Richardsonian Romanesque architectural-style to honor the late daughter of Lumber Baron Captain and Mrs. Andrew Tainter…

…looks on the inside like the acknowledged Moorish architecture of the Alhambra in Grenada, Spain.

Yet, again, we are taught that the indigenous people of this land were uncivilized tribes of hunter-gatherers.

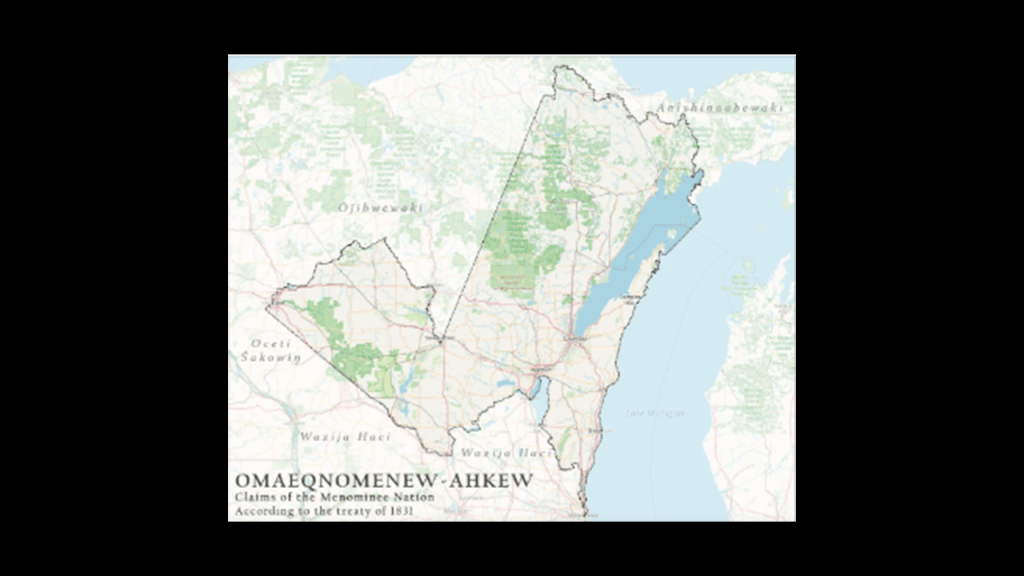

This painting is by an artist named Paul Kane, who died in 1871, called “Fishing by Torchlight,” of the Menominee spearfishing at night by torchlight and canoe on the Fox River.

The traditional land of the Menominee People was on the western shore of the Lake Michigan, particularly around the Green Bay region.

This region was also a location where the Jesuits set up shop early on as well.

What I am also seeing from tracking leylines all over the Earth, looking from place-to-place at cities in alignment over long-distances, are the consistent presence of swamps, marshes, bogs, deserts, dunes, and places where it appears land masses sheared-off and submerged under the bodies of water we see today.

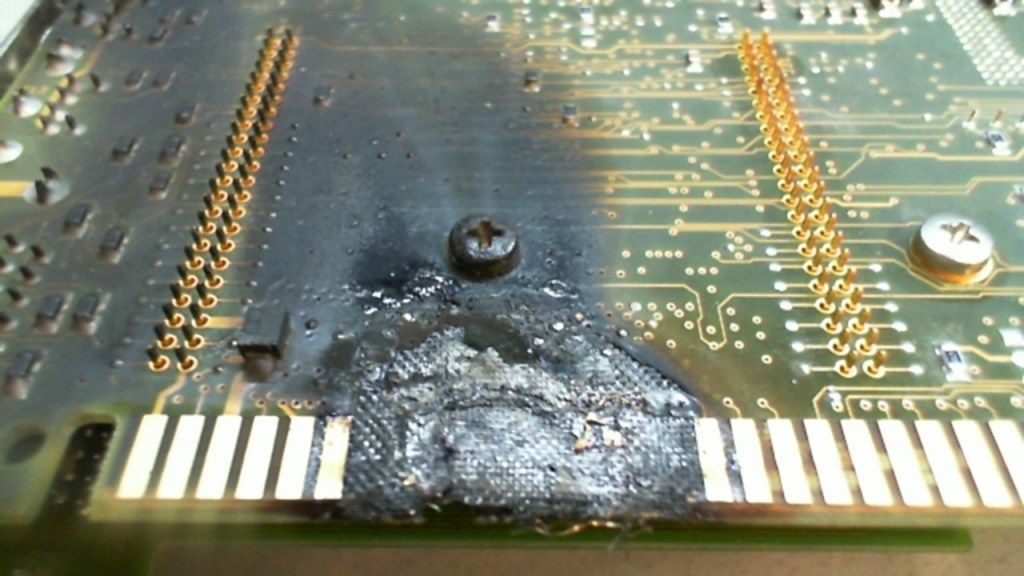

My working hypothesis is that the circuit board of the Earth’s original energy grid system was deliberately blown out by one or more forms of directed frequency or energy of some kind into different places on the Earth’s energy grid, causing the surface of the Earth to undulate and buckle.

I believe the beings behind the cataclysm were shovel-ready to dig enough of the original infrastructure out of the ruined Earth so they could be used and civilization restarted, which I think started in earnest in the mid-to-late 1700s and early 1800s.

Then they only used the pre-existing infrastructure until they found replacement fuel sources that could be monetized and controlled by them for what had originally been a free-energy power grid and transportation system worldwide, and when what remained of the original infrastructure was no longer useful to them, or inconvenient to their agenda, they had it destroyed, discontinued, or abandoned, typically in a very short time after it was said to have been constructed.

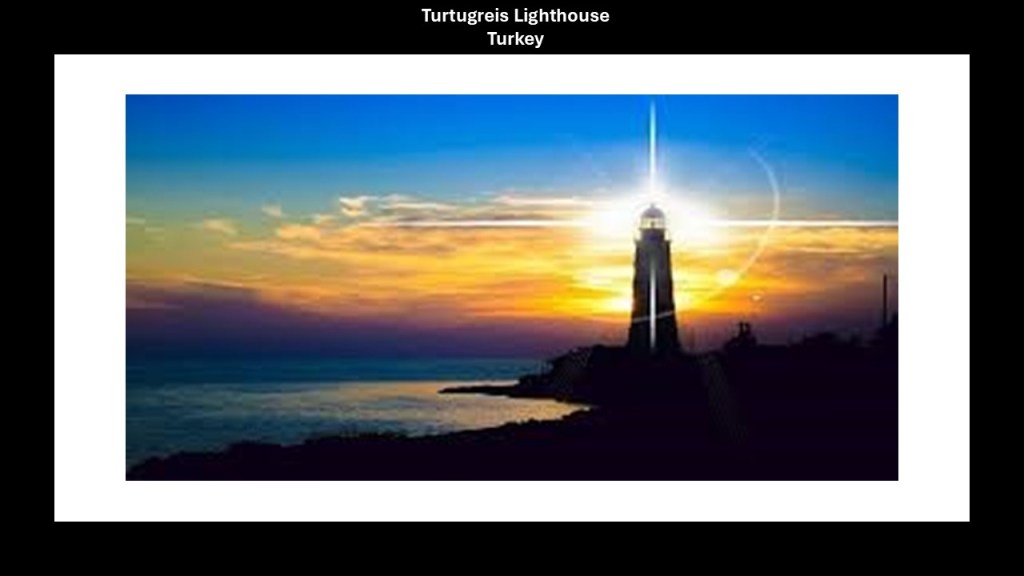

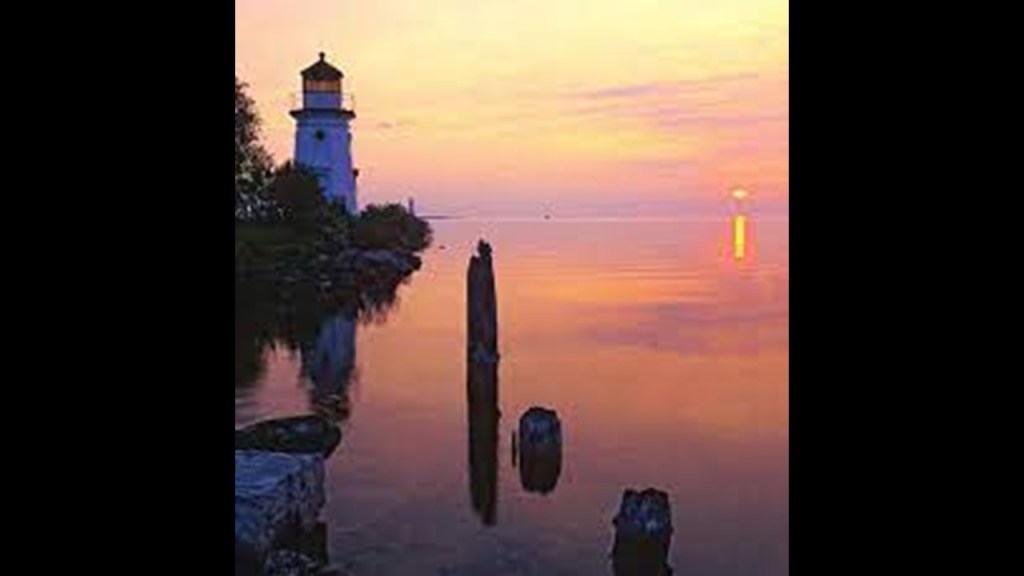

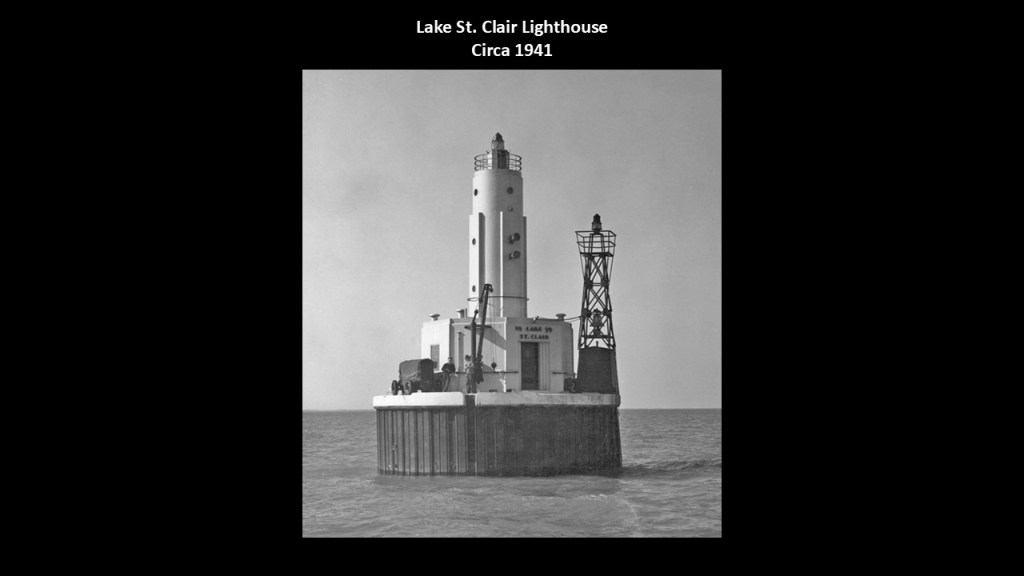

Like everything else we have been told to explain what is in existence in our world, I really don’t believe lighthouses were built to guide ships by whom they were said to have built them when they were said to have been built.

What I am seeing is that they ended up next to the edge of water when the land around them sank, and were repurposed into navigational aids in the New World to guide ships through the now sunken and broken landmasses in the surrounding waters.

I have come to believe “lighthouses” were literally “houses for light” for the purpose of precisely distributing light energy generated by this gigantic integrated system that existed all over the Earth that was in perfect alignment with everything on Earth and in heaven.

So two of the many points of comparison between the Great Lakes in this series will include lighthouses, and the bathymetry of the lakes, which is the measurement of the depth of water in the lakes.

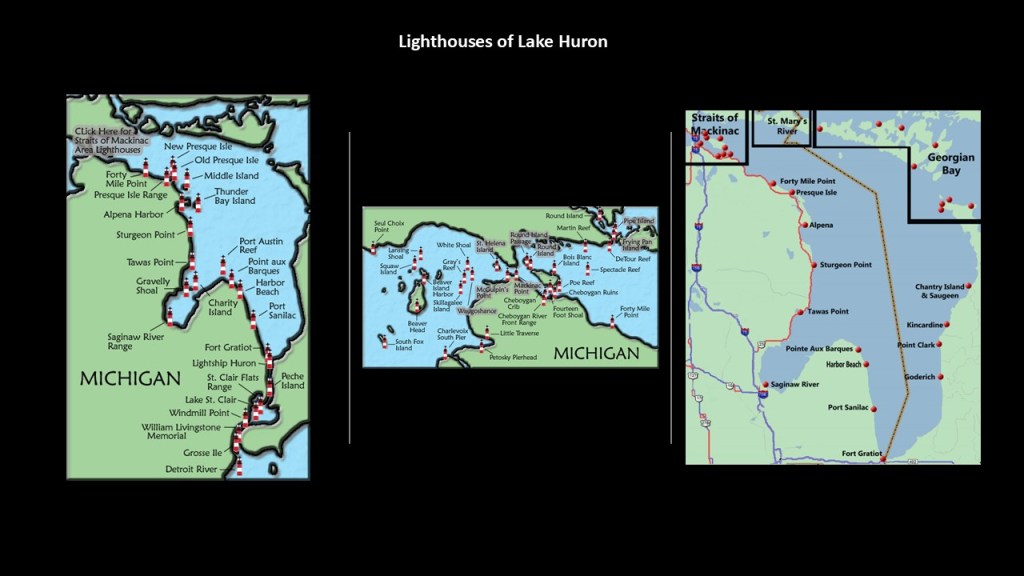

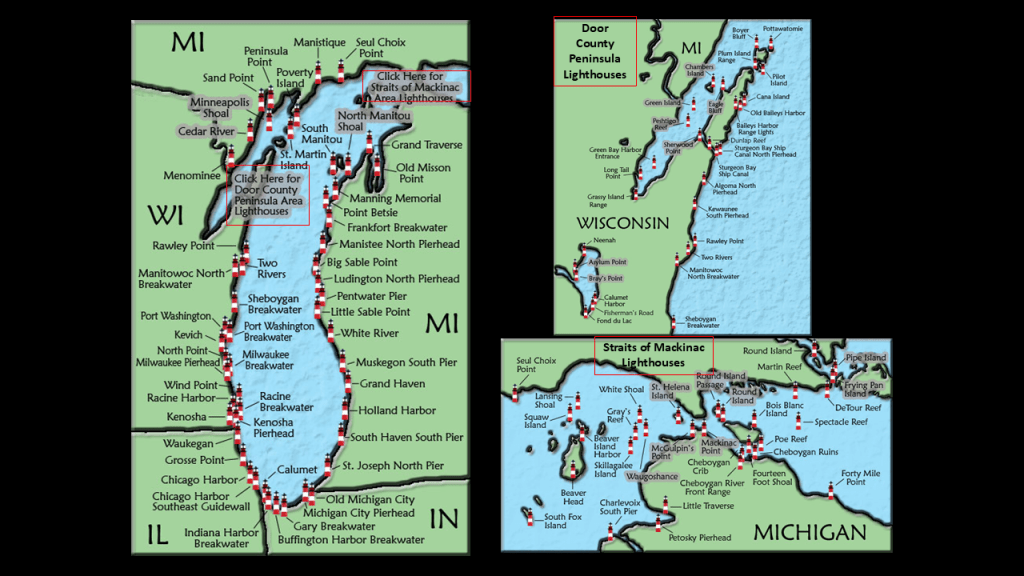

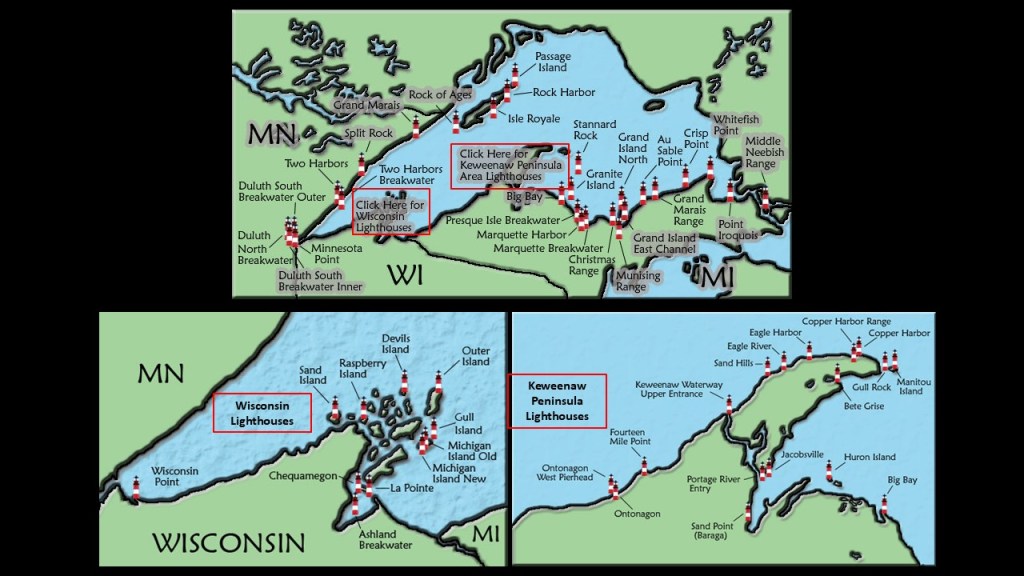

First, the lighthouses of Lake Huron.

From what I could find out in a search, the Great Lakes have been home to approximately 379 lighthouses, with 200 of them still active, and that Lake Huron has seventy lighthouses around its shores.

There are approximately 88 lighthouses along the shore of Lake Michigan, which has more lighthouses than any of the Great Lakes.

There are approximately 78 lighthouses around Lake Superior, with 42 of them being in Michigan.

One of Michigan’s nicknames is “The Lighthouse State,” as it has more lighthouses than any other state.

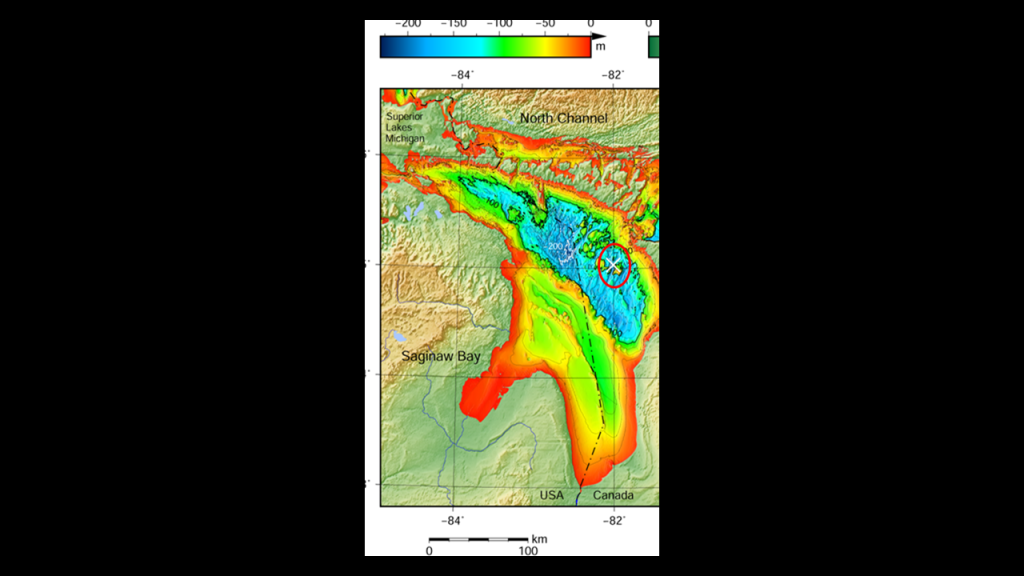

Next, the bathymetry of the Straits of Mackinac and Lake Huron.

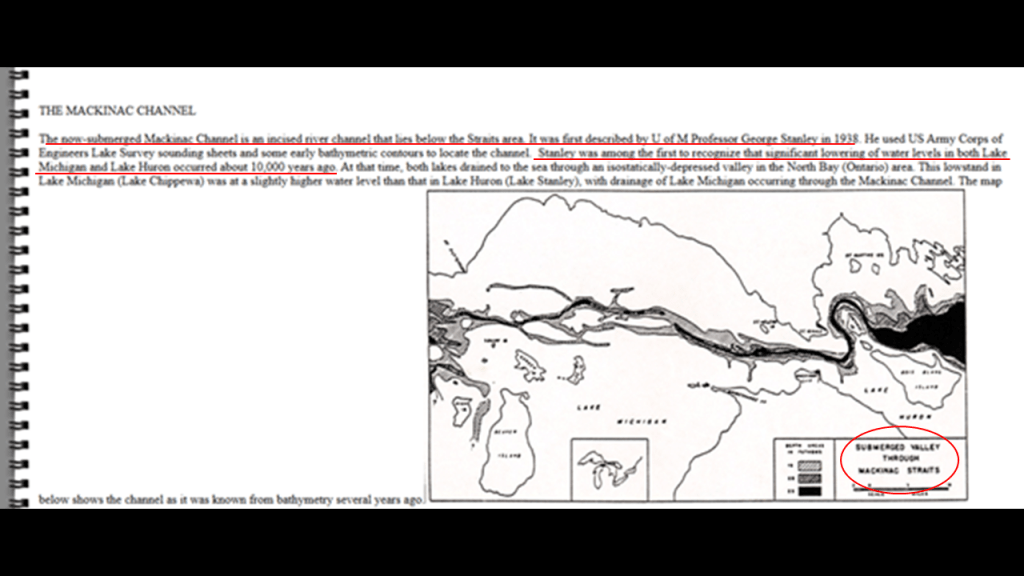

The bathymetry of the Straits of Mackinac and the Mackinac Channel in between Lake Michigan and Lake Huron shows the depth of the water to be quite shallow, ranging in depth from primarily 0- to 50-meters, or 164-feet.

The Straits of Mackinac are described as a submerged valley in the legend in the lower right-hand corner, and the Mackinac channel as a now-submerged, incised river channel that lies below the straits area.

As mentioned in the top paragraph, these features have been ascribed to a significant lowering of the water levels in Lake Michigan and Lake Huron that occurred 10,000-years-ago.

Interesting to note the S-shaped bends of the Mackinac Channel, and particularly the one going around Mackinac Island in Lake Huron.

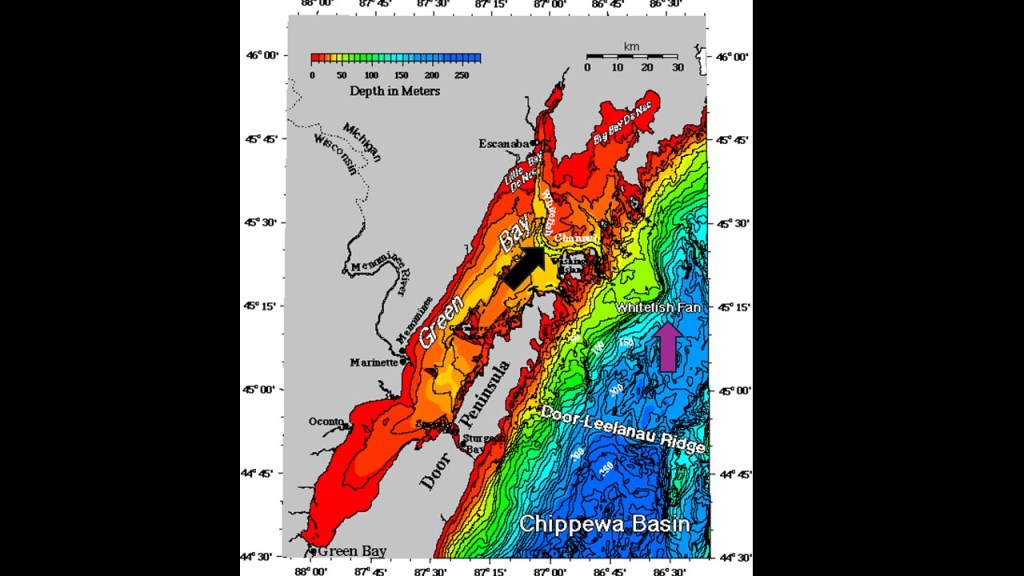

I found the same thing in the Au Train-Whitefish Channel of the Green Bay region of Lake Michigan.

The Au Train – Whitefish Channel is a large, submerged channel beginning in Little Bay de Noc and extends across the floor of Green Bay and around Washington Island.

Washington Island is one of a string of islands which are an outcropping of the Niagara Escarpment that stretch across the entrance of Green Bay from the Door Peninsula in Wisconsin to the Garden Peninsula in Michigan.

The strait separating Washington Island and the Door Peninsula is a treacherous waterway littered with shipwrecks.

I will be talking a great deal more about the Niagara Escarpment where it enters Lake Huron on the Ontario-side as it is the landform between Lake Huron and Georgian Bay.

The Niagara Escarpment runs predominantly east-to-west, from New York, through Ontario, Michigan, Illinois, and Wisconsin, with a nice, half-circle shape, attached to a straight-line, when drawn on a map.

Similar to the Mackinac Channel, I found an explanation given for the continuation of the underwater channel that when Lake Michigan was in a low stage, the Au Train Whitefish River cut a deep channel in the basin of Lake Michigan.

But what if these channels are actually submerged man-made waterways, and part of a sophisticated canal and hydrological system?

S-shaped bends are found in what are called rivers all over the surface of the Earth.

These are just a few of countless examples.

As we are seeing here in the bathymetry of Lake Michigan and Lake Huron, these same S-shapes are found underwater.

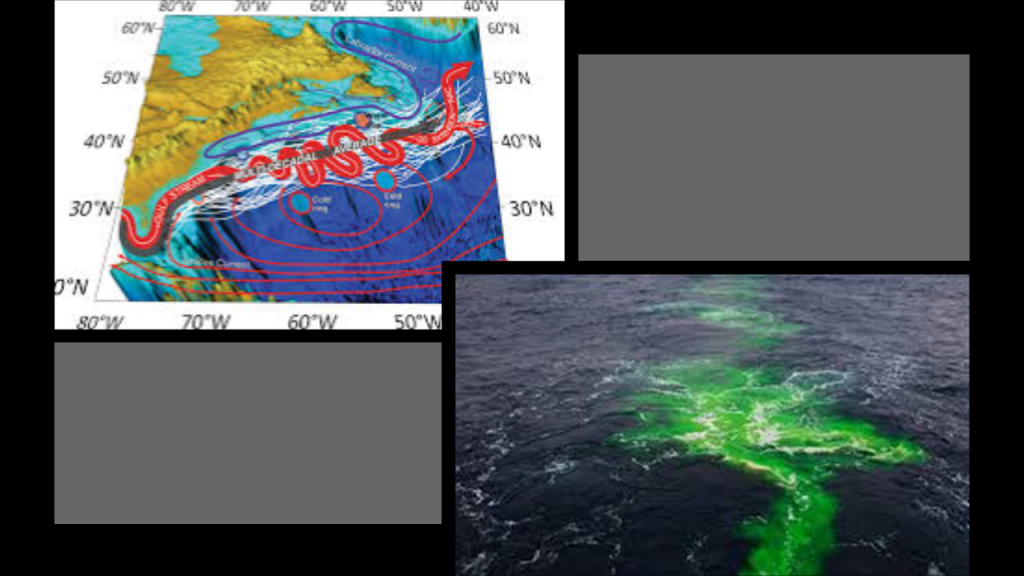

The same can be said for the Gulf Stream in the Atlantic Ocean.

I found on the official USGS.gov website that “The Gulf Stream can be thought of as a “river” in the ocean.”

For example in this slide, there is a graphic showing the Gulf Stream with snaky, S-shaped bends on the top left, and on the bottom right, a photograph of the Gulf Stream, looking like a river in the ocean.

Another examples of this same finding is seen a photo taken in the waters of the Great Barrier Reef, looking very much like a river in shallow water.

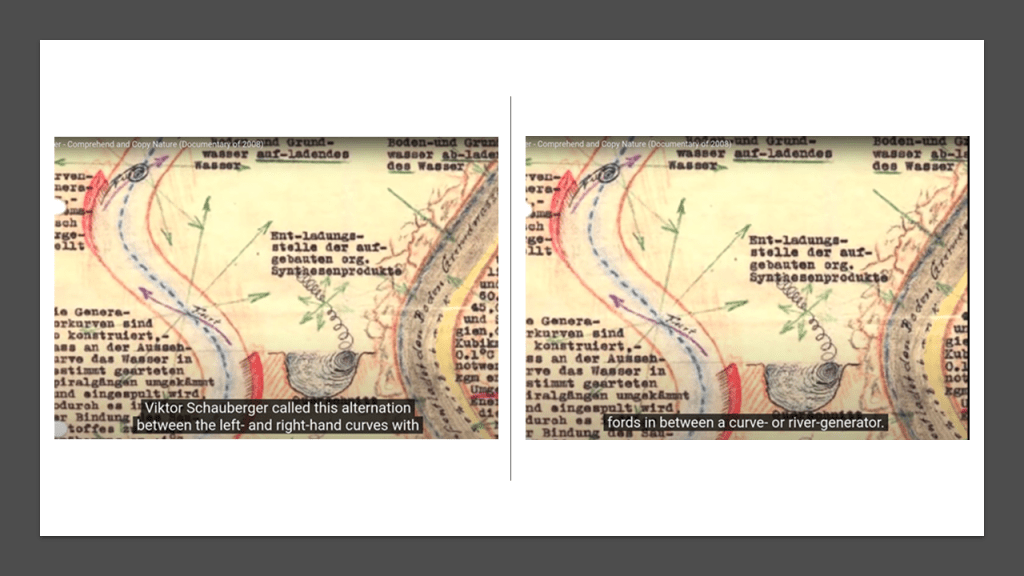

As described in Viktor Schauberger’s work on the hydrodynamics of S-shapes, the motions of this water flow energizes water, and I would surmise it is highly likely that is what these S-shaped water courses were doing in the original energy grid system.

Schauberger was a pioneer in the field of water and energy research in the early 20th-century, and was working on developing a device for the production of living water, water with an enhanced structure and necessary minerals.

Conversely, he believed that modern industries destroy healthy water, including the processes of municipal water treatment plants, which decompose healthy water.

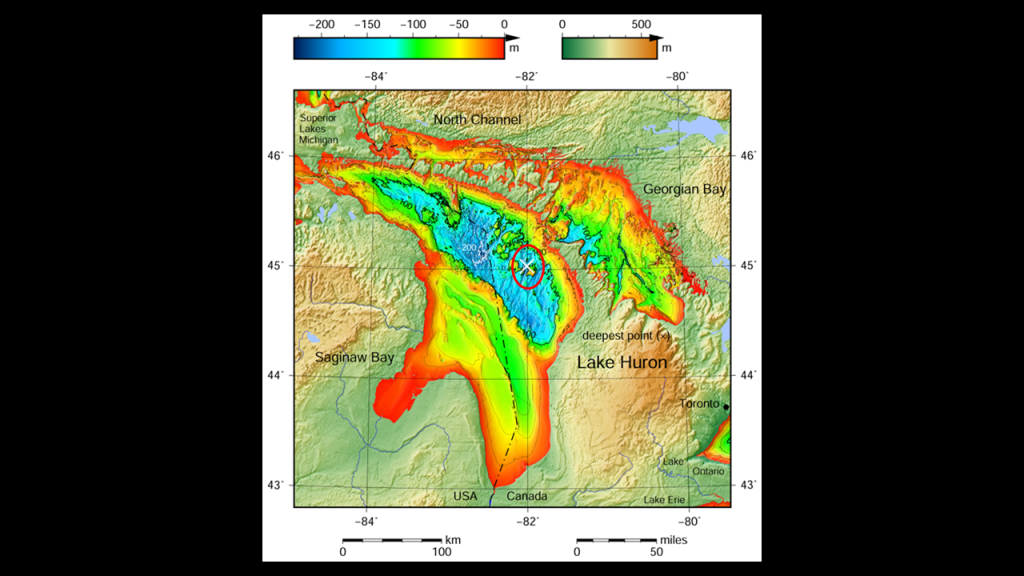

With regards to the bathymetry of Lake Huron and its Georgian Bay, the water- depth ranges from 0 to 100-meters, or 328-feet, for the most part throughout both of them, with the deepest part of Lake Huron being in the middle at 229-meters, or 750-feet in depth where the “x” is circled in red.

The average depth of what constitutes Lake Huron is 59-meters, or 195-feet.

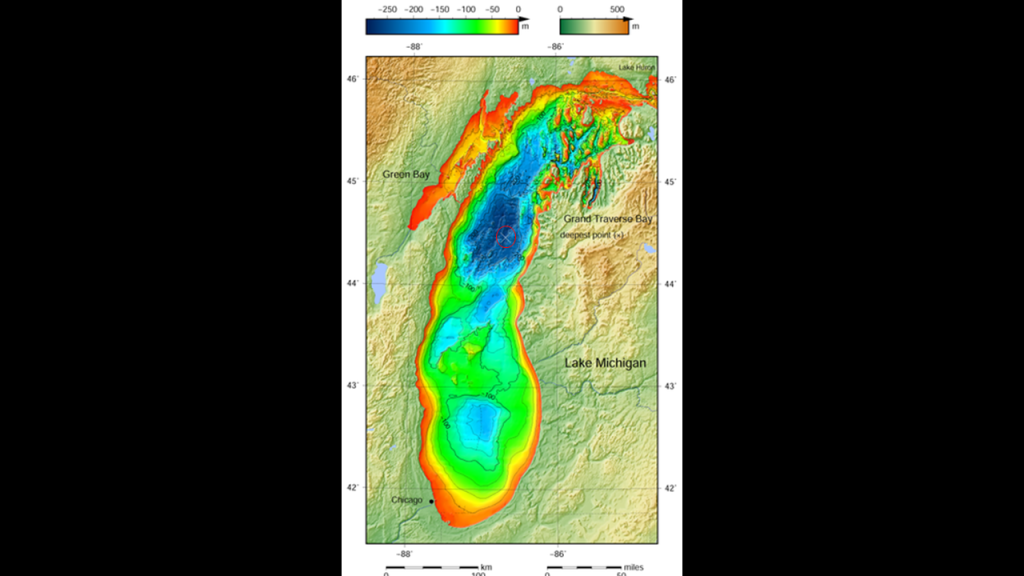

The bathymetry of Lake Michigan shows shallows around the edges ranging from 0 to around 100-meters, or 0- to around 328-feet, with an uneven lake-floor towards the middle ranging in depth from 100-meters, to its deepest point at 282-meters, or 925-feet, which is marked by the “x” circled in red.

The average depth of Lake Michigan is 85-meters, or 279-feet.

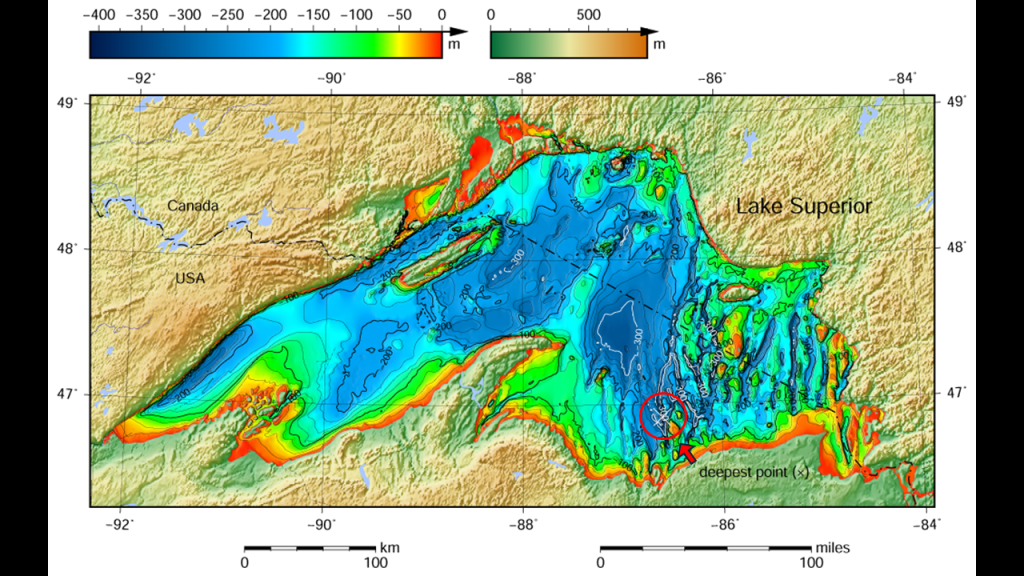

The bathymetry of Lake Superior also shows its shallows around the edges, which range from 0 to around 100-meters, or 0- to around 328-feet, with an uneven lake-floor ranging in depth from 100-meters, to its deepest point at 406-meters, or 1,333-feet.

Lake Superior’s average depth is 147-meters, or 483-feet.

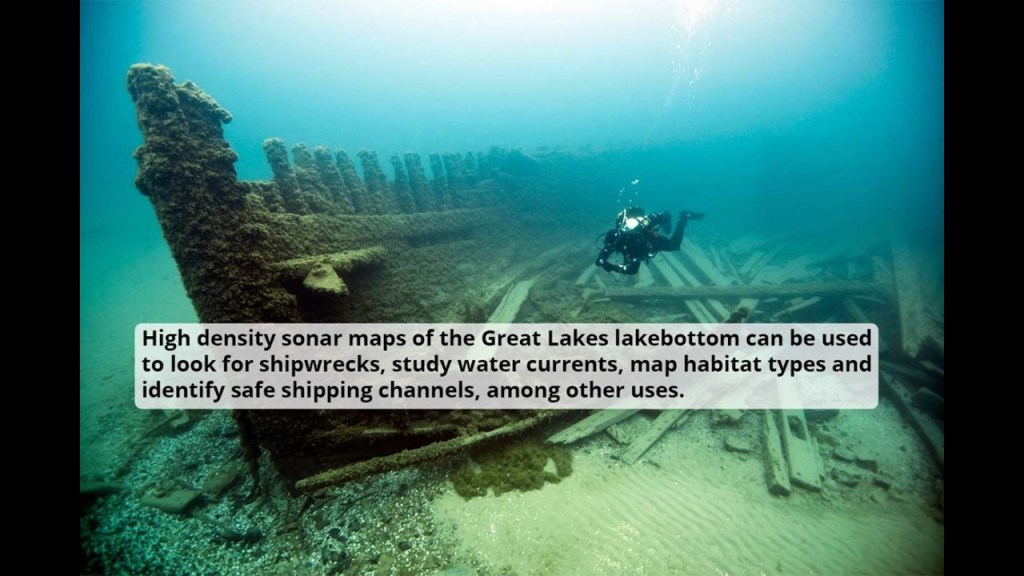

The Great Lakes Region is notorious for its shipwrecks, with an estimated somewhere between 6,000 to 10,000 ships and somewhere around 30,000 lives lost.

The reasons given for the high number of shipwrecks consist of things like severe weather, heavy cargo and navigational challenges.

There are estimates of over 1,000 shipwrecks in Lake Huron…

…with reasons given of storms, islands, and shallow areas.

The Thunder Bay National Marine Sanctuary alone, also known as “Shipwreck Alley,” is estimated to have 116 known shipwrecks.

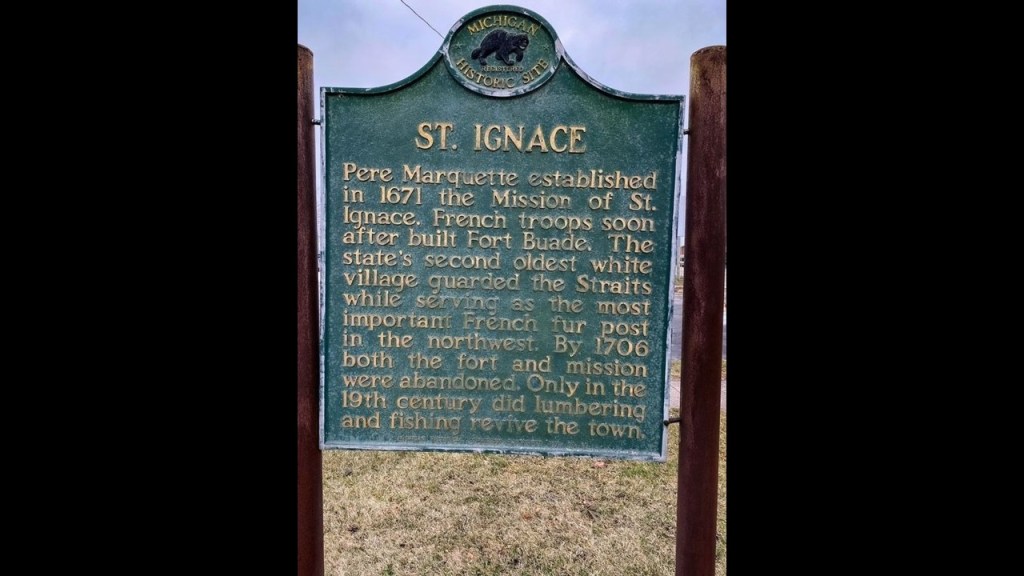

I am going to start at St. Ignace, which is where I ended the Lake Michigan part of this series as it is on Lake Huron on the other end of the Mackinac Bridge from Mackinaw City, where Lakes Michigan and Huron meet.

Mackinaw City is at the tip of the Lower Peninsula of Michigan, and St. Ignace is at the bottom of Michigan’s Upper Peninsula, with the Straits of Mackinac separating the two places.

There are a few things I am going to bring forward from the last post about St. Ignace, and a few things I am going to add here.

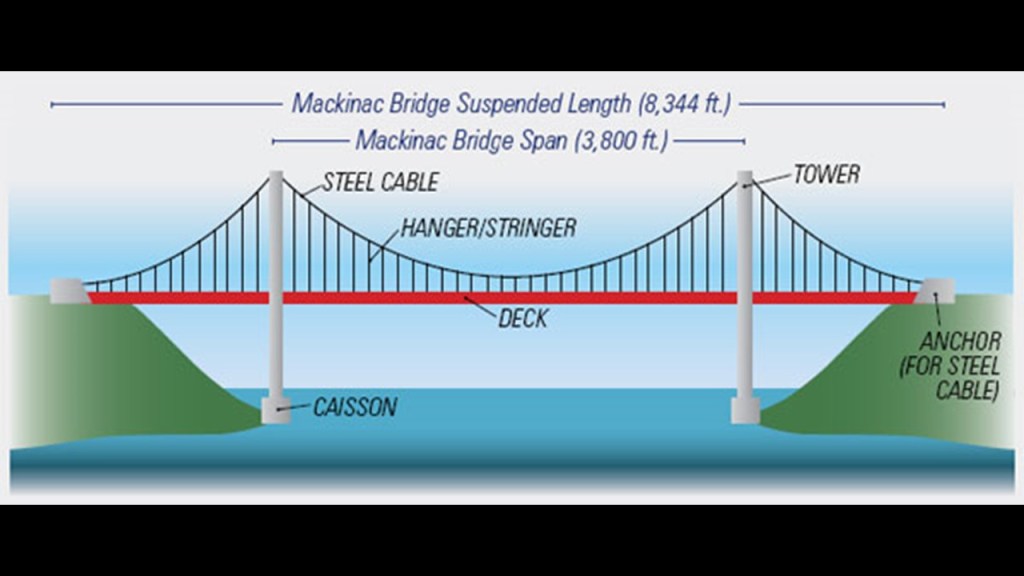

The Straits of Mackinac are crossed by the Mackinac Bridge, which was said to have first opened in 1957.

The Mackinac Bridge carries Interstate 75 across the longest suspension bridge between anchorages in the western hemisphere between Mackinaw City at its southern end, and St. Ignace at the northern end.

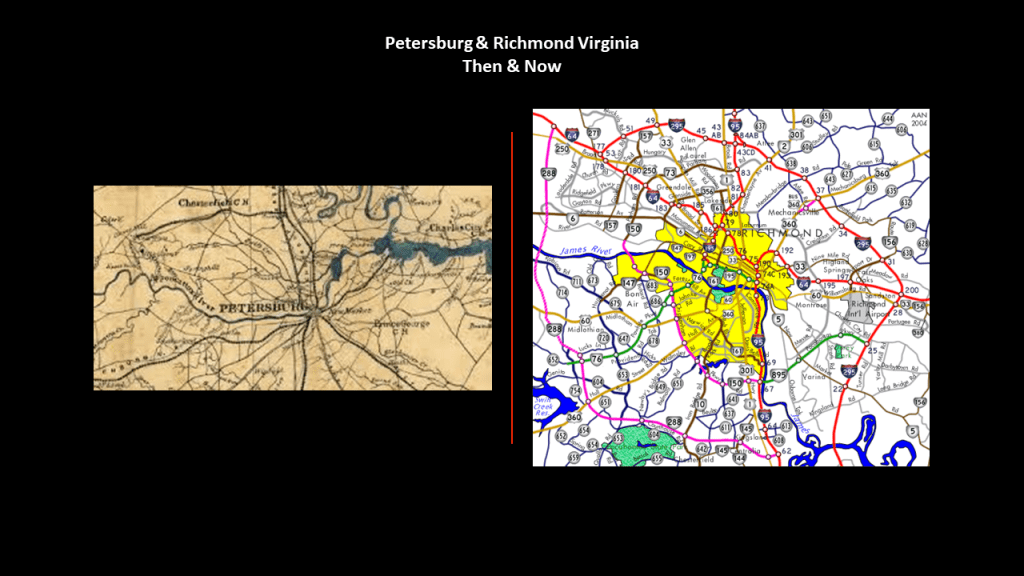

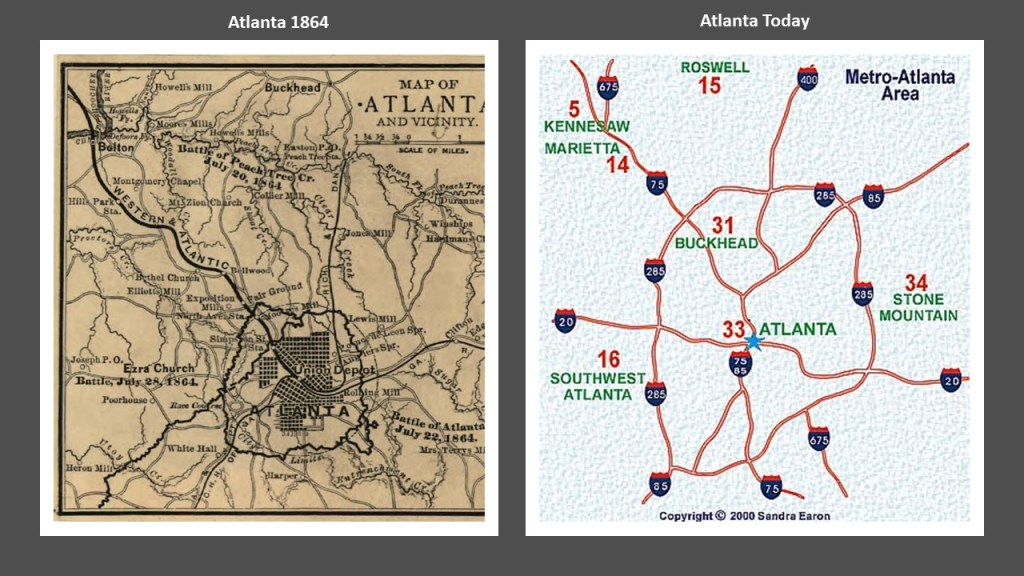

The northern terminus of Interstate-75 is Sault Ste. Marie in Michigan north of St. Ignace, and the southern terminus is in Miami, Florida, and it crosses through a whole lot of major cities in-between on its 1,786-mile, or 2,875-kilometer, length, including, but not limited to Saginaw, Bay City, and Detroit adjacent to Lake Huron in Michigan; Toledo, Dayton, and Cincinnati in Ohio, Richmond in Virginia, and Atlanta in Georgia.

The European history of St. Ignace began when Father Jacques Marquette founded the St. Ignace Mission here in 1671, and named it after the founder of the Jesuits, St. Ignatius of Loyola.

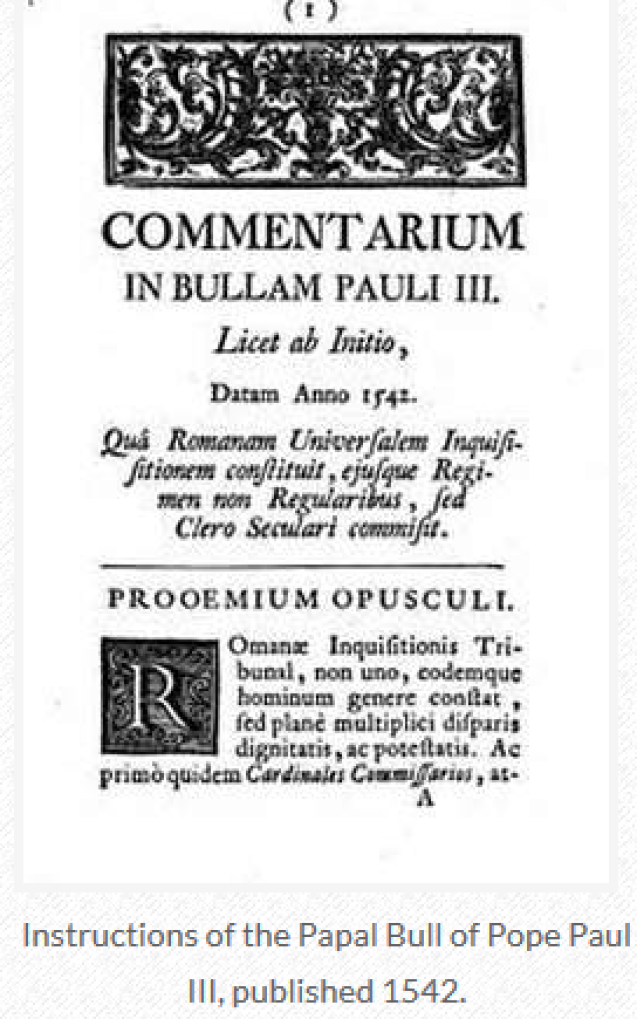

In our historical narrative, Pope Paul III issued a papal bull forming the Jesuit Order in 1540, under the leadership of Ignatius of Loyola, a Basque nobleman from the Pyrenees in Northern Spain.

The Jesuit Order included a special vow of obedience to the Pope in matters of mission direction and assignment.

Whoever the Jesuits and the Freemasons were are at the top of my list of suspects for who was primarily responsible for giving us our new, fabricated historical narrative.

Two years later, in the year of 1542, we are told Pope Paul III established the Holy Office, also known as the Inquisition and the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith.

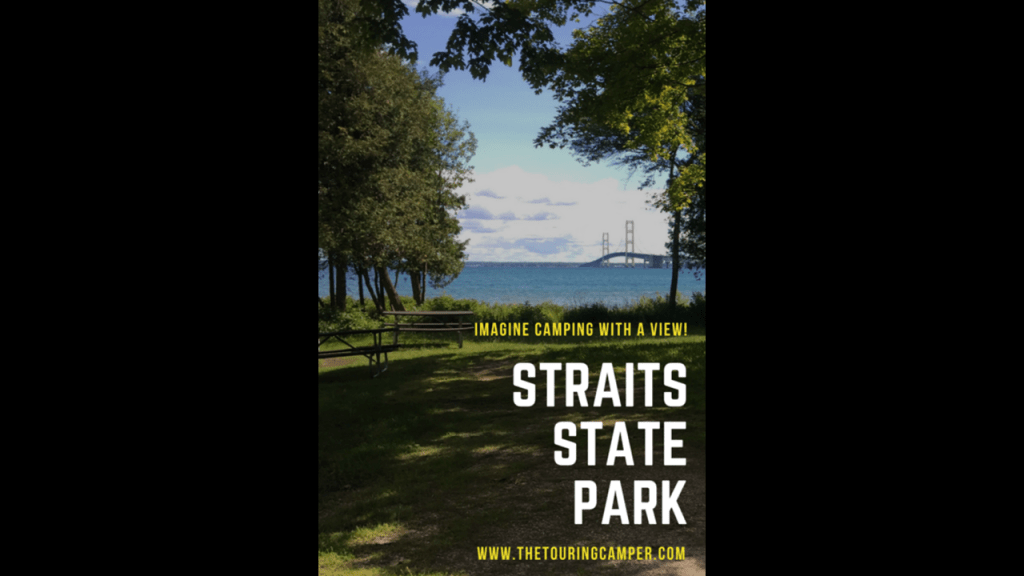

The Straits State Park on the northern shores of the Straits of Mackinac is a popular camping spot.

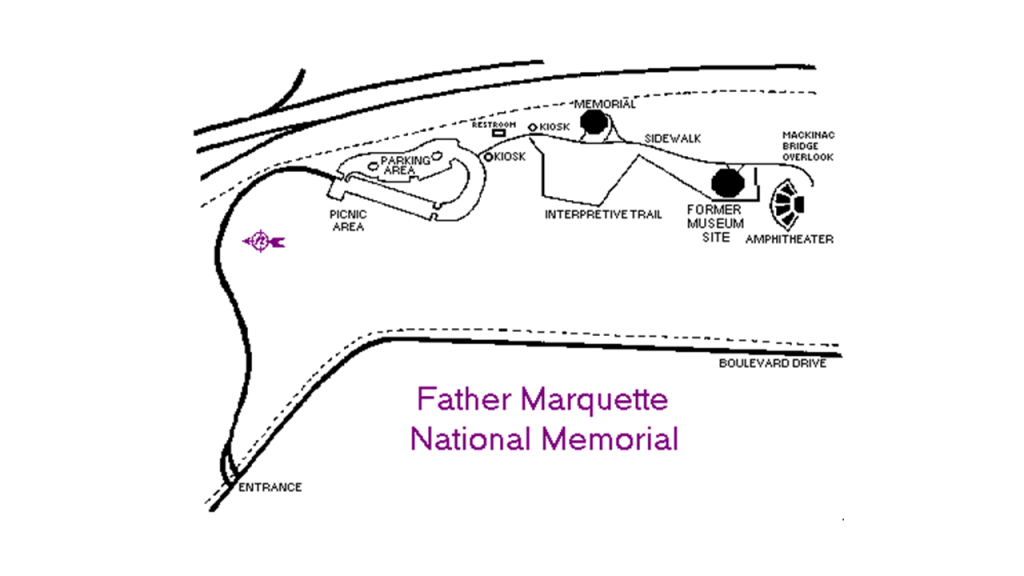

It is also the location of the Father Marquette National Memorial, which was established in December of 1975 to pay tribute to his life and work.

The Father Marquette Museum building at the Memorial was destroyed by fire in March of 2000.

The main building today houses exhibits, and there is a fifteen-station interpretative trail.

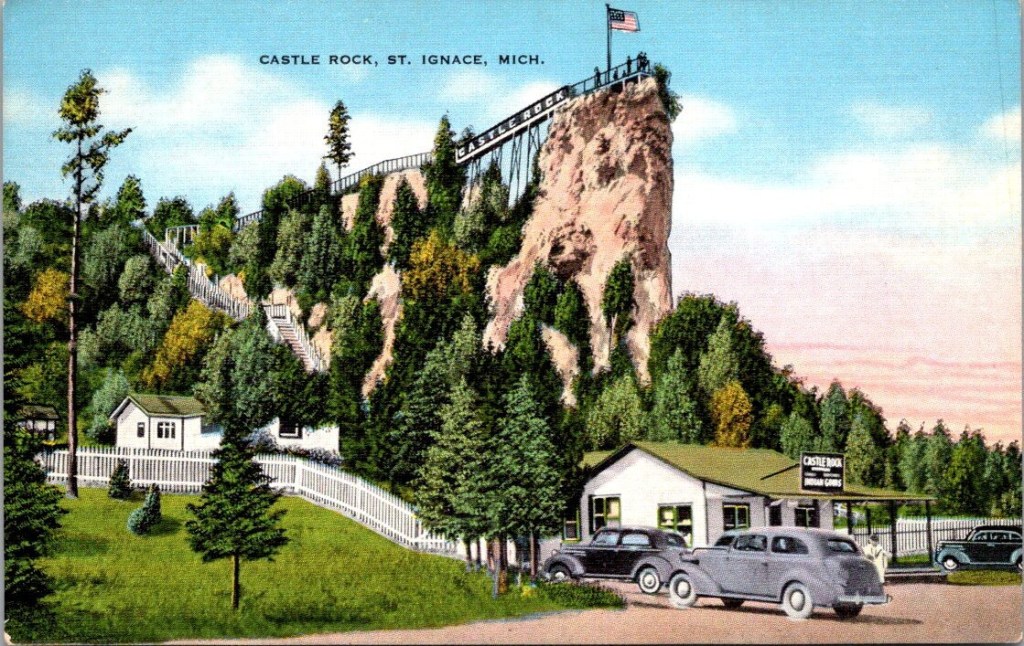

One of the popular places to visit in St. Ignace is Castle Rock.

It is described as a limestone stack that rises 196-feet, or 59-meters, above Lake Huron, and we are told was created by the erosion of surrounding land from the melting of Ice Age glaciers after the Wisconsinan Glaciation, called the most recent glacial period of the North American ice-sheet complex that peaked more than 20,000-years ago.

It is three-miles north of St. Ignace on I-75.

Just a short-distance further up the road from Castle Rock is another limestone formation called “Rabbit’s Back.”

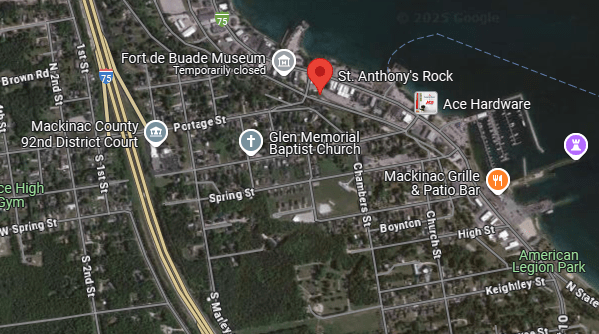

St. Anthony’s Rock is found in the town of St. Ignace, between the Fort de Buade Museum and the Wawatam Lighthouse.

St. Anthony’s Rock is yet another one of what is called a limestone seastack and tourist attraction in St. Ignace.

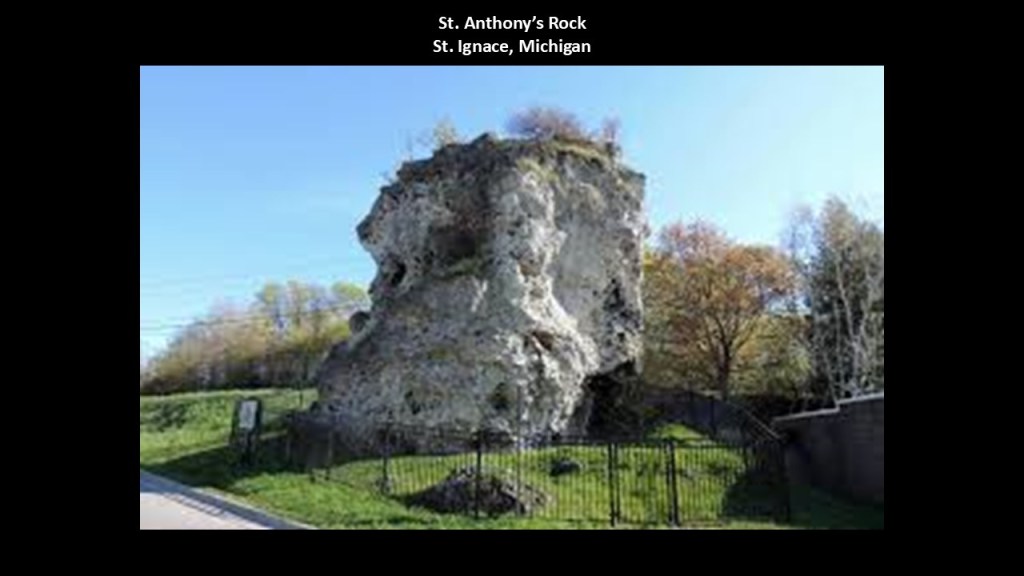

Limestone was a common building material in the ancient world, and used in constructions like the Pyramids of Giza…

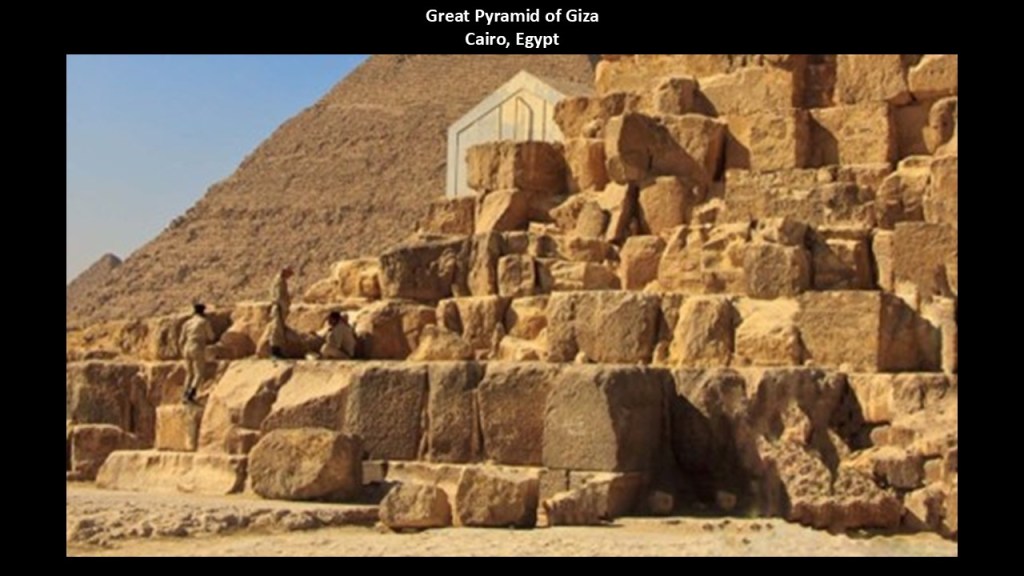

…and the Western Wall, also known as the “Wailing Wall,” an ancient limestone wall in the old city of Jerusalem.

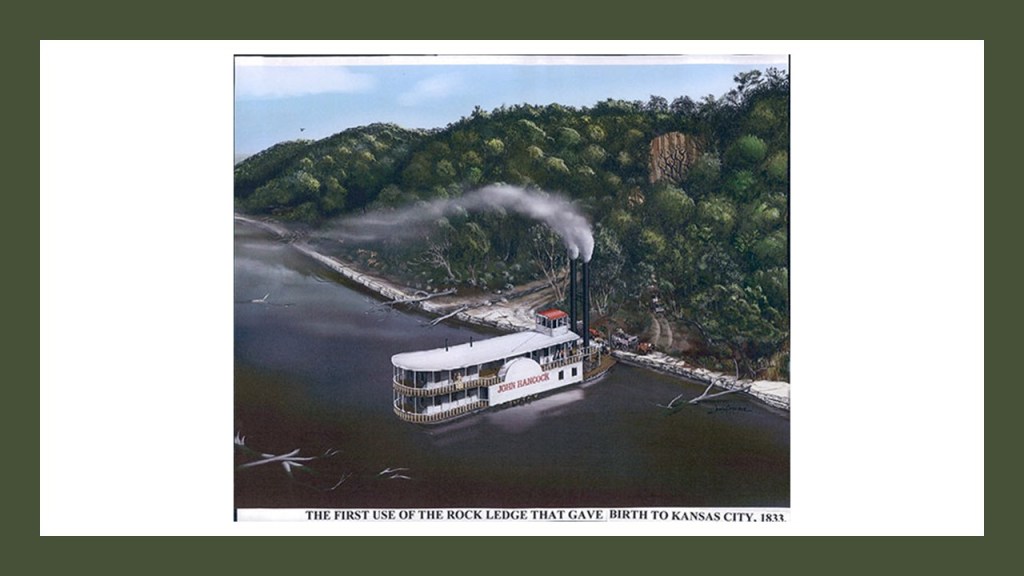

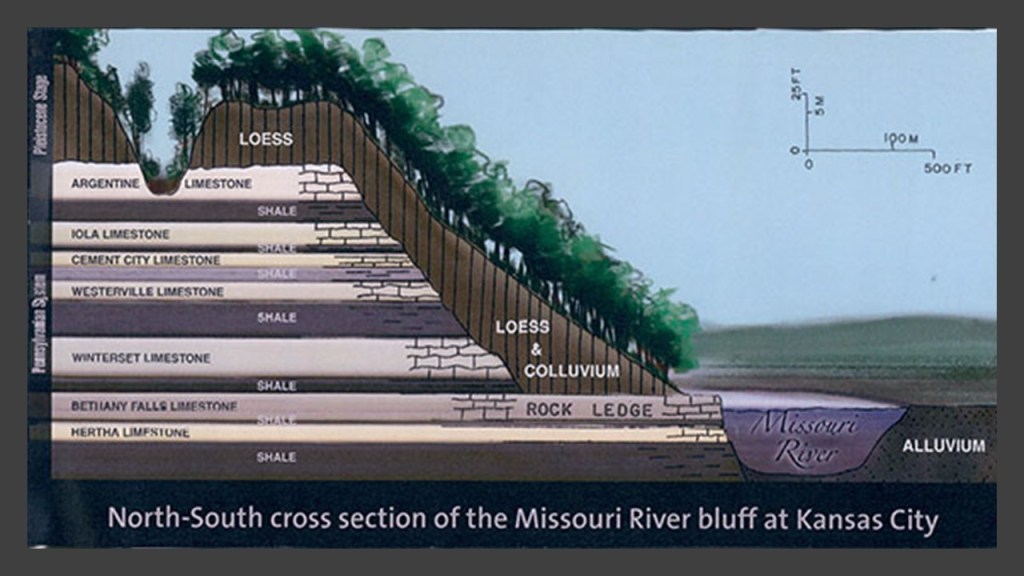

In other places in the early history of the United States, we are told that a rock ledge became the landing place for riverboats and wagon trains starting in 1833, on the southside of the Missouri River at what became Kansas City, Missouri.

And all of these strata of limestone underneath the surface were identified where this particular rock ledge was located.

Keep all this in mind as we go around the shores of Lake Huron and its Georgian Bay in this post.

Next, the Wawatam Lighthouse on the other side of St. Anthony’s Rock in St. Ignace is located at the far end of the former railroad ferry pier used by the Chief Wawatam railroad and passenger ferry in the marina.

I would like to mention more about the Wawatam Lighthouse and the Chief Wawatam ferry here.

Firstly, what we are told about the Wawatam Lighthouse in our historical narrative is that it was built as an architectural folly for the Michigan Department of Transportation (DOT) in 1998 as a non-functional lighthouse as an element of the tourist heritage of the state for the Welcome Center on I-75 at Monroe, Michigan, but that in 2004, the Michigan DOT slated the lighthouse for demolition when it was deemed obsolete when the Welcome Center was renovated.

The state government agreed to move the structure to another location when concerns were raised about this decision, and when St. Ignace officials learned of this, they applied for it, and got it moved there.

Anyway, that is what they tell us about it, but I have my doubts.

Secondly I would like to mention the Chief Wawatam railroad ferry.

It was a coal-fired steel ship primarily based in St. Ignace that operated year-round in the Straits of Mackinac between St. Ignace and Mackinaw City between 1911 and 1984 serving in its storied career as a train and passenger ferry and as an icebreaker.

The first part of the Chief Wawatam’s history is that it’s main purpose was as a train service to carry railroad cars, though it also operated as a passenger and car ferry over the years.

It served as an icebreaker during the winter months until that function was replaced by the U. S. Coast Guard Icebreaker Mackinaw in 1944, and that the ship’s passenger service also dropped off after World War II.

Passenger service ended after the Mackinac Bridge opened in 1957, and it was used exclusively as a railroad ferry until 1985.

The Chief Wawatam railroad ferry was the only railroad connection between the two peninsulas of Michigan, and in the 1950s, transported 30,000 railroad cars per year across the Straits of Mackinac.

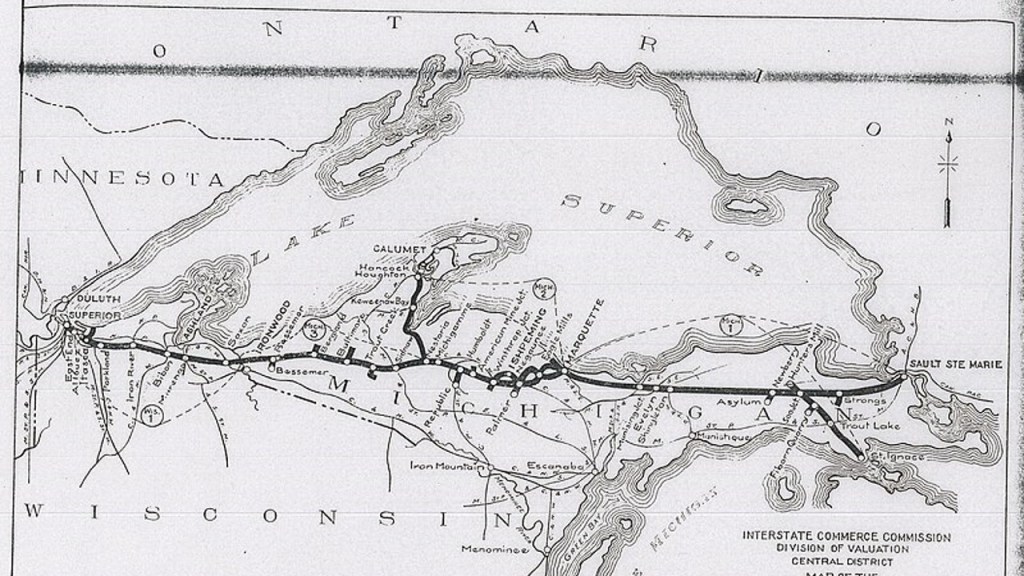

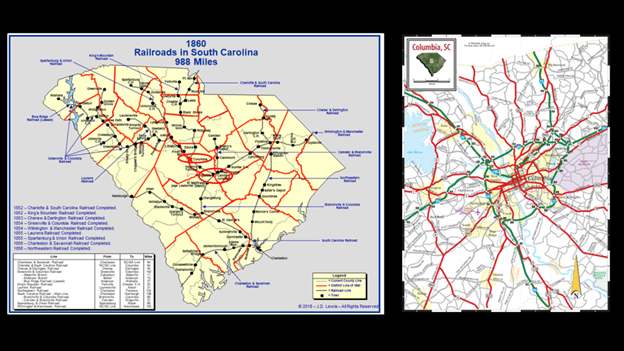

It started servicing the Mackinac Transportation Company in 1911, a joint-venture of the Duluth, South Shore, and Atlantic Railway; the Grand Rapids and Indiana Railway; and the Michigan Central Railroad since all three railroads crossed back and forth at the Straits of Mackinac.

The Duluth, South Shore, and Atlantic Railway was American railroad that served the Upper Peninsula of Michigan, and the Lake Superior shoreline of Wisconsin, providing service from Sault Ste. Marie, Michigan, and St. Ignace, Michigan, westward through Marquette to Superior, Wisconsin, and Duluth, Minnesota.

The first of this railway line started operating in 1855; then came under the control of the Canadian Pacific Railway in 1888; and was in operation all together from 1855 to 1960 as an independently-named subsidirary of the Canadian Pacific Railway.

What’s left of it was merged to the Soo Line in 1961.

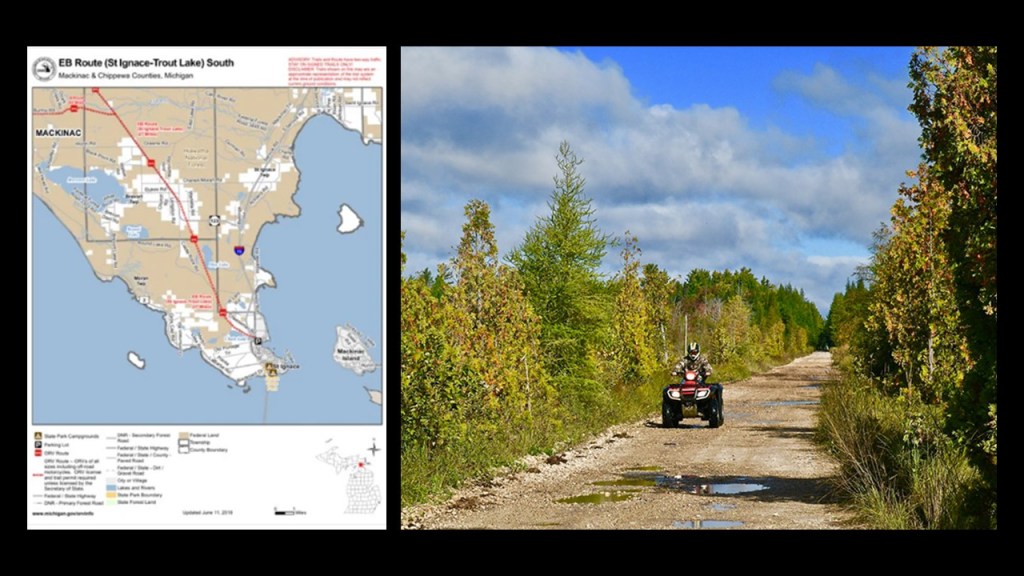

Parts of the Duluth, South Shore, and Atlantic Railway were converted to rail-trails, like the St. Ignace – Trout Lake Trail, which is 26-miles, or 42-kilometers, of multi-use recreational trail in its former railbed.

With regards to railroad lines to Mackinaw City on the other side of the Straits of Mackinac, we are told that the Michigan Central Railroad came to Mackinaw City from Detroit in 1881, and the Grand Rapids and Indiana Railroad in 1882 connecting Mackinaw City to Traverse City; Grand Rapids; and Fort Wayne in Indiana.

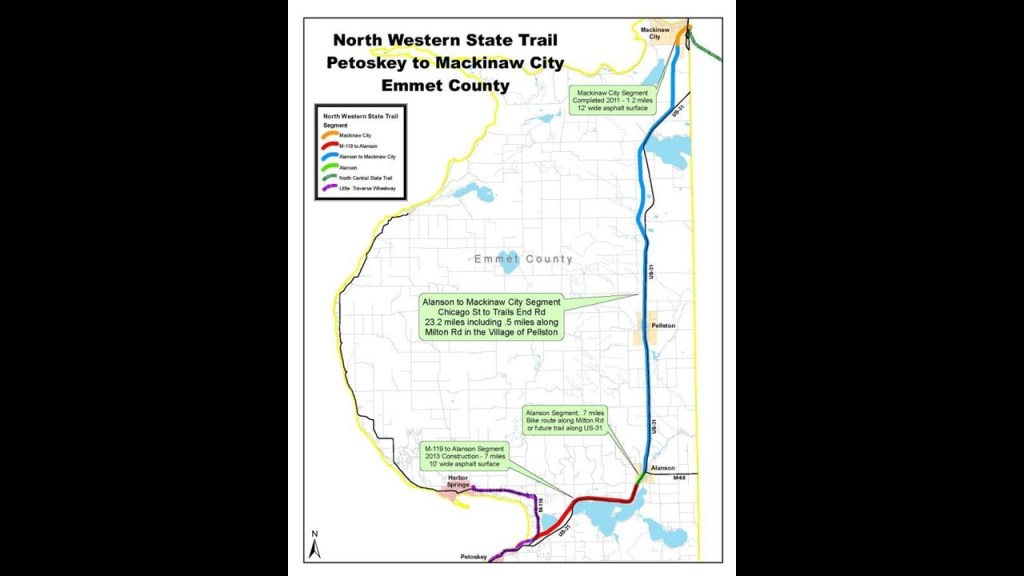

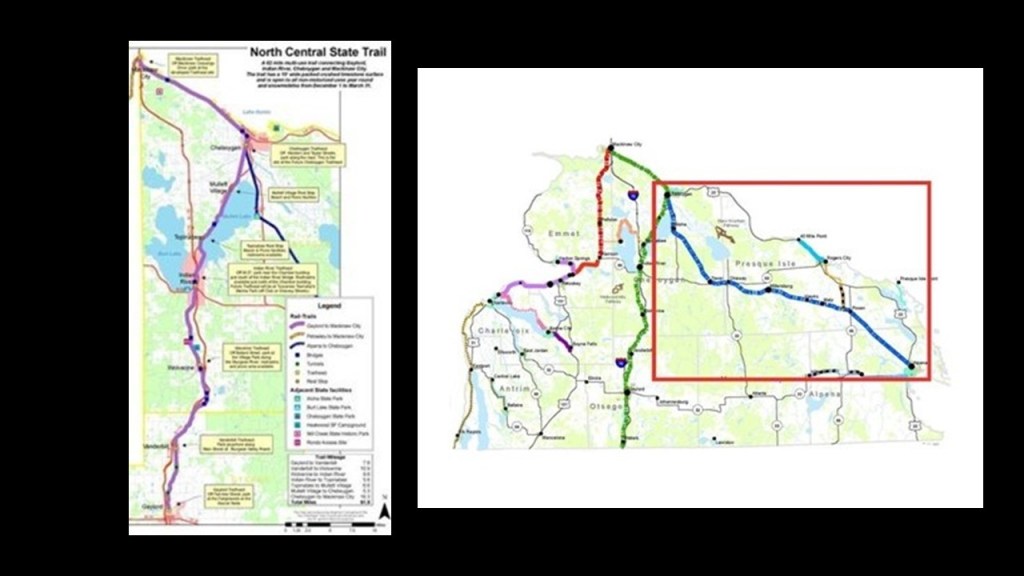

The former rail-lines have been repurposed into Rail-trails, like the North West State Trail from Petoskey…

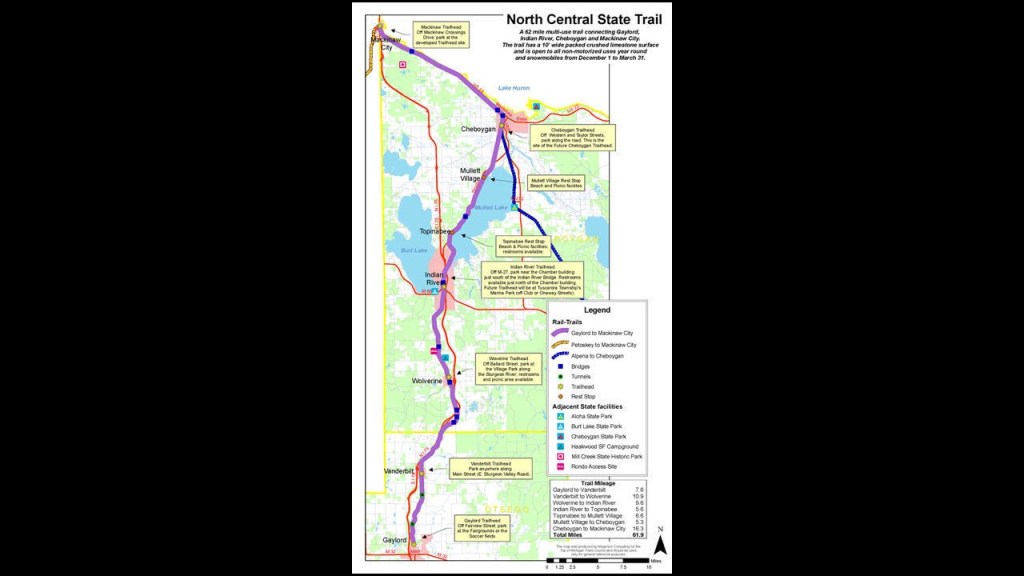

…the North Central State Trail from Gaylord…

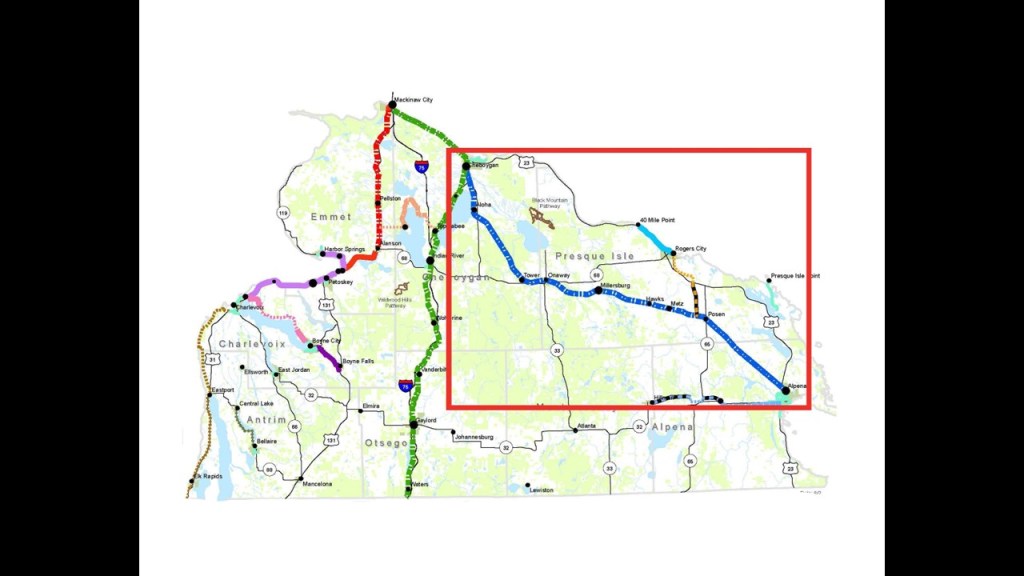

…and the North Eastern State Trail from Alpena.

There were two historic roundhouses in Mackinaw City, one for each of the railroads serving the area.

They were both demolished after the rail-lines leading to Mackinaw City were scrapped sometime in the 1980s.

The location of the former Michigan Central Roundhouse is now a Burger King, and the Grand Rapids and Indiana Railroad is a parking lot west of the Mackinac Bridge; and the former railyards a shopping mall.

Like the lighthouses, I believe that all the rail infrastructure was part of the original energy grid, and as I’ve said many times, I believe the energy grid was deliberately destroyed, and that it’s destruction created everything we see in the world today that we are told is natural, including, but not limited to, the Great Lakes, and I will continue to show you evidence for why I believe this is the case throughout this post and this series on the Great Lakes.

I think the Controllers’ removed the rail-lines that were original part of the energy grid when they were no longer needed for mining and/or their agenda, and they only kept what was needed for freight, with keeping some for public transportation where it was critical infrastructure and scaled passenger service way-back from what it once was.

They were instead turned into interstates, highways, roadways, and recreational rail-trails. used for harvesting our energy for the benefit of a few from what was the original free-energy grid system for the benefit of all.

Now I am going to turn my attention to what’s found in the Straits of Mackinac and Lake Huron to the east of the Mackinac Bridge, Starting with Mackinac Island.

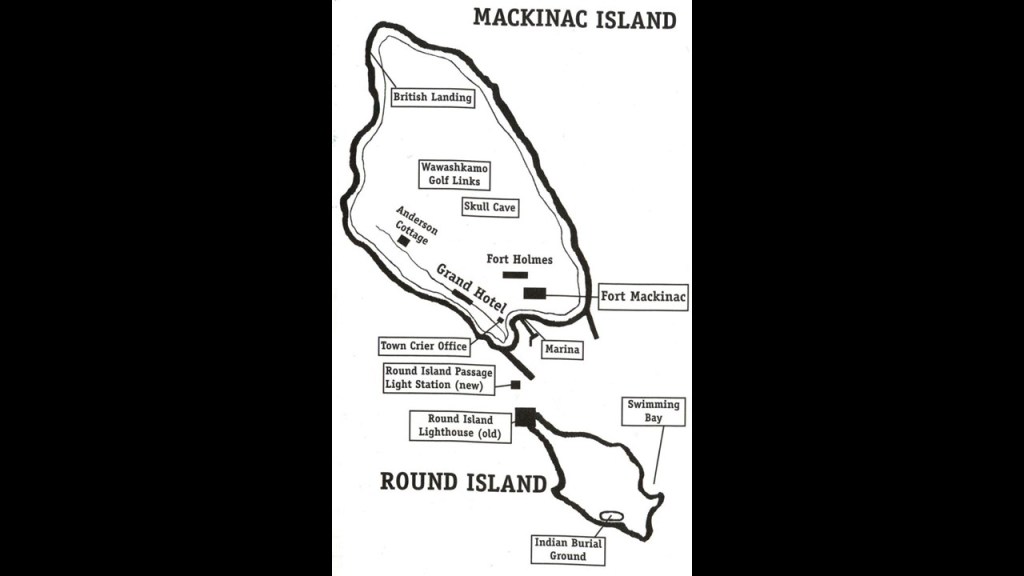

This is what we are told about Mackinac Island.

It was long home to an Ottawa settlement and previous indigenous civilizations before European colonization in the 1600s, and became a strategic center of the fur trade in the Great Lakes region.

We are told that the British built a limestone fort known as Fort Mackinac during the American Revolutionary War in 1781 to control the Straits of Mackinac, and by extension, the Great Lakes’ fur trade.

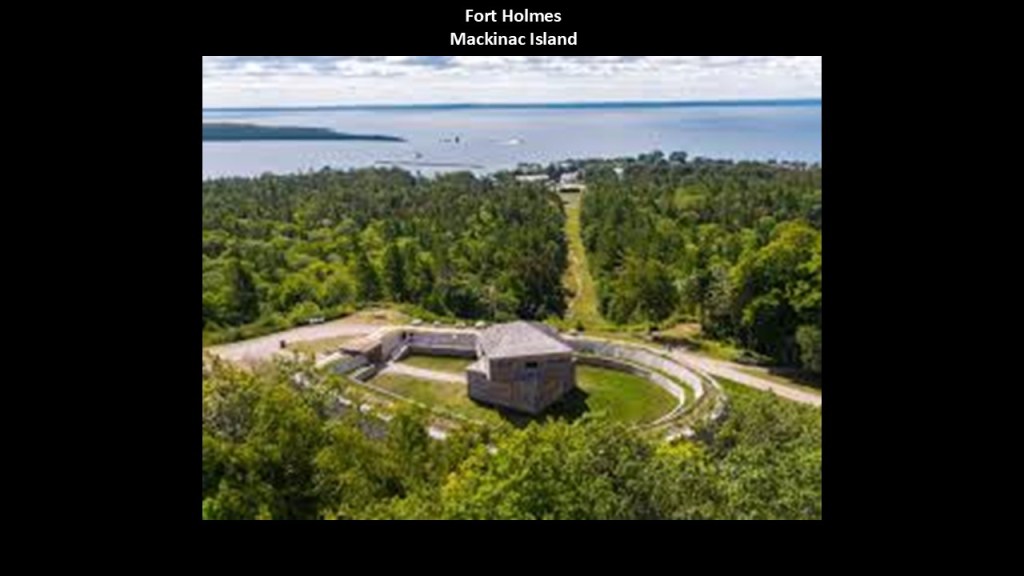

Still for control of the Great Lakes, we are told the 4.35-square-mile or 11.3-kilometer-squared, in size Mackinac Island was the location of two battles during the War of 1812, which took place at the location on the island identified as the “British Landing,” and in which the British took control of the island for a few years.

We are told that Fort Holmes was built on the highest point of Mackinac Island by the British in 1814, and was taken possession of by United States Armed Forces as part of the Treaty of Ghent in 1815, which was the peace treaty that ended the War of 1812.

The Grand Hotel on Mackinac Island was said to have been constructed in the late 19th-century.

We are told in our historical narrative that in 1886, the Michigan Central Railroad, the Grand Rapids and Indiana Railroad, and the Detroit and Cleveland Steamship Navigation Company formed the Mackinac Island Hotel Company.

We are told they purchased the land and construction of the hotel began based on a design by Detroit architects Mason and Rice, and it first opened in 1887, a year later.

Still operating as a resort today, in its history it has been a destination for Presidents and famous people in our narrative.

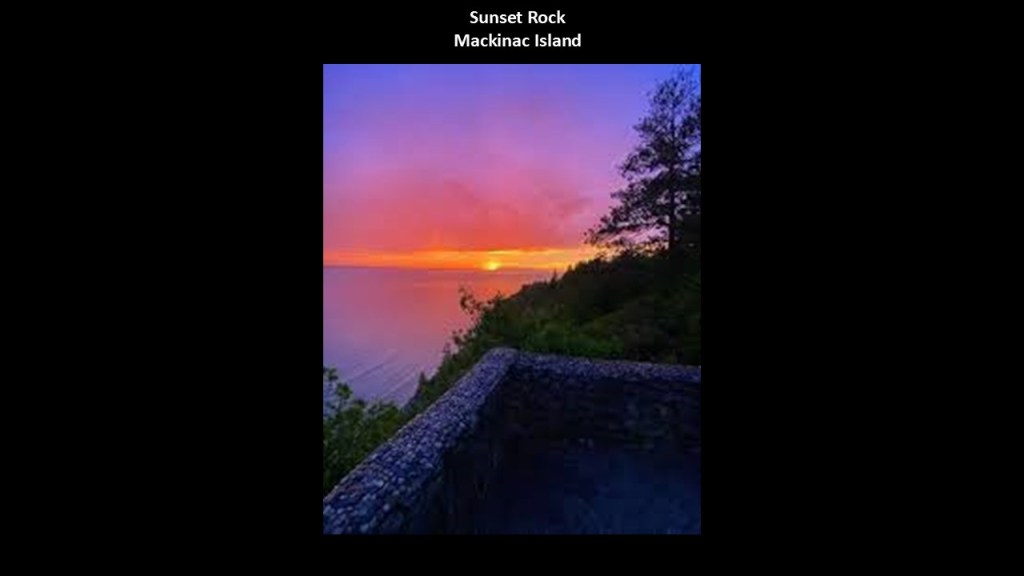

Sunset Rock is a stone look-out on Mackinac Island with great views of the Straits of Mackinac, the bridge, and the sunset.

Interesting to note the shores of Mackinac Island lined with megalithic stone blocks.

Arch Rock is the most famous of the rock formations and is described as a natural geological formation that is 50-feet, or 15-meters, -wide, and towers above the water.

Here is a photo showing Arch Rock in alignment with the Milky Way.

Round Island is a little island in-between Mackinac Island and Bois Blanc Island.

The most noteworthy thing about the uninhabited Round Island are its lighthouses – the Round Island Passage Light Station and the Old Round Island Lighthouse.

The Round Island Passage Lighthouse was said to have been constructed starting in 1947 and operational in 1948.

The Round Island Channel that it is located in is a navigable waterway in Lake Huron and a key link in the lake freighter route between Lake Michigan and Lake Superior on which millions of tons of taconite iron ore are shipped annually, and has been an essential element in shipping the iron ores from northern Minnesota since the late 1800s.

The Old Round Island Lighthouse is located on the west shore of Round Island in the shipping lanes of the Straits of Mackinac, and was said to have been constructed in 1895.

It was seen in the 1980 movie “Somewhere in Time” which was filmed primarily on Mackinac Island.

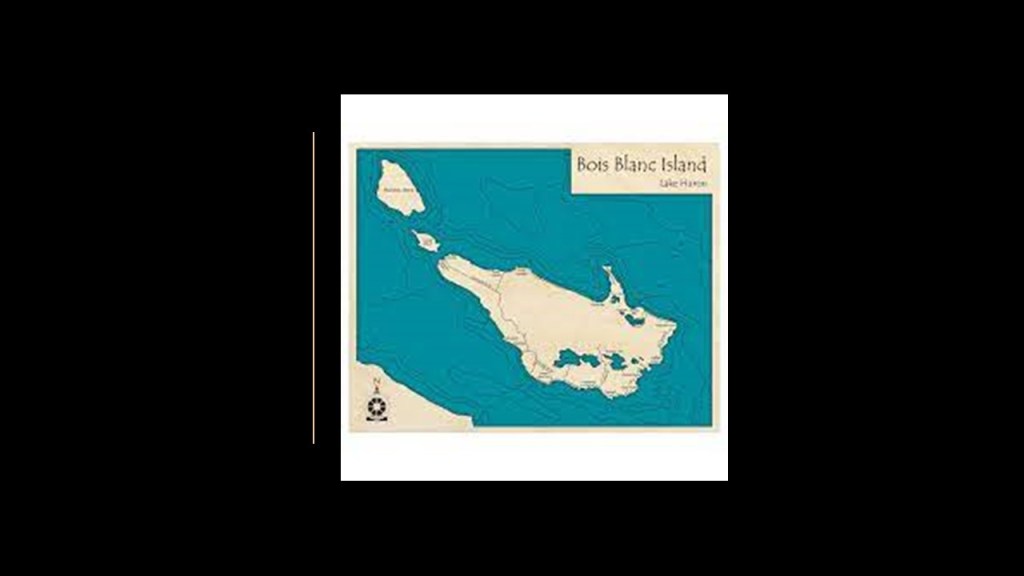

Bois Blanc Island is on the other side of Round Island from Mackinac Island.

“Bois Blanc,” or “white wood,” is believed to be a reference either to the paper birch tree or basswood, which is called “bois blanc” in other contexts.

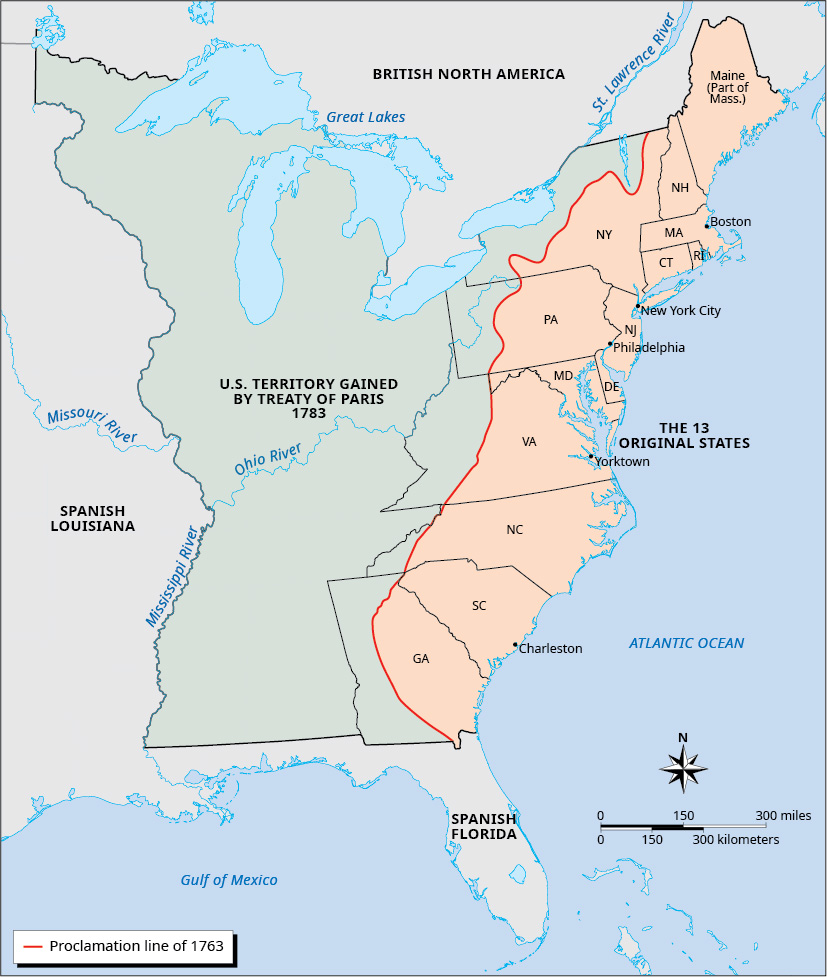

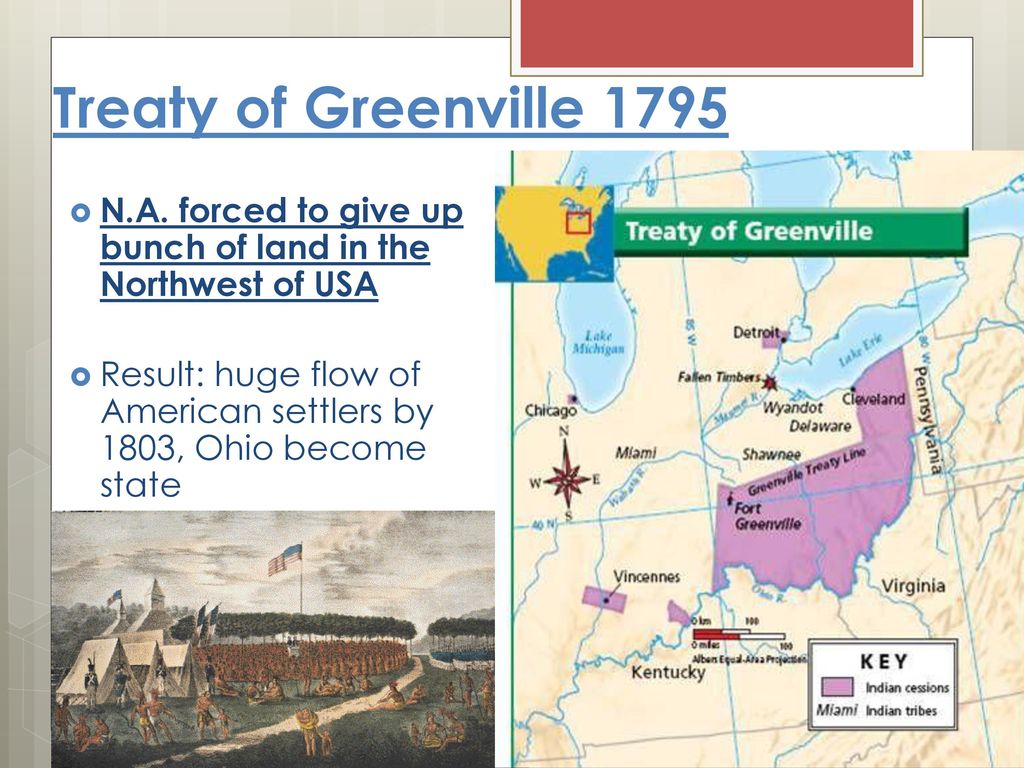

We are told in our historical narrative that Bois Blanc Island was ceded by the Chippewa “as an extra and voluntary gift” to the United States government in the 1795 Treaty of Greenville between the United States and the indigenous nations of the Northwest Territory for their lands for settlement after their defeat in the Battle of Fallen Timbers in August of 1794, ending what we are told was the Northwest Indian War took place in this region between 1786 and 1795 between the United States and the Northwestern Confederacy, consisting of the indigenous people of the Great Lakes area.

The Territory had been granted to the United States by Great Britain as part of the Treaty of Paris at the end of the Revolutionary War.

The area had previously been prohibited to new settlements, and was inhabited by numerous indigenous peoples, even though the British maintained a military presence in the region.

The 1795 Greenville Treaty forced the displacement of the indigenous people from most of Ohio, in return for cash and promises of fair treatment.

The community of Bois Blanc Township is on the island with a population of 100 in the 2020 Census, and has the smallest school district in terms of student enrollment in the nation, with three students in 2024 – 2025.

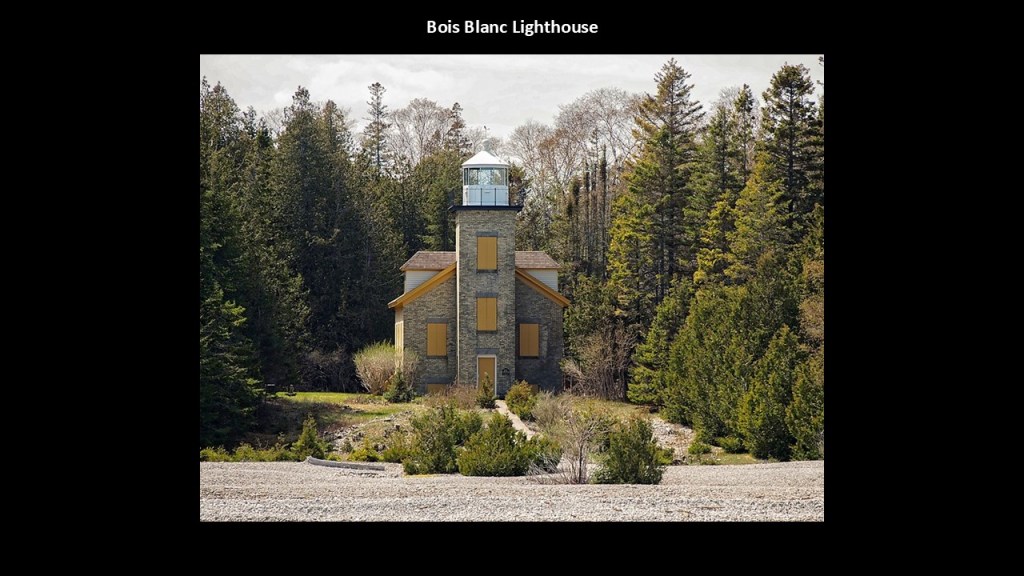

The Bois Blanc Lighthouse was said to have been constructed in 1867, two years after the end of the American Civil War.

It is on the northern end of the island is not in use and is privately-owned.

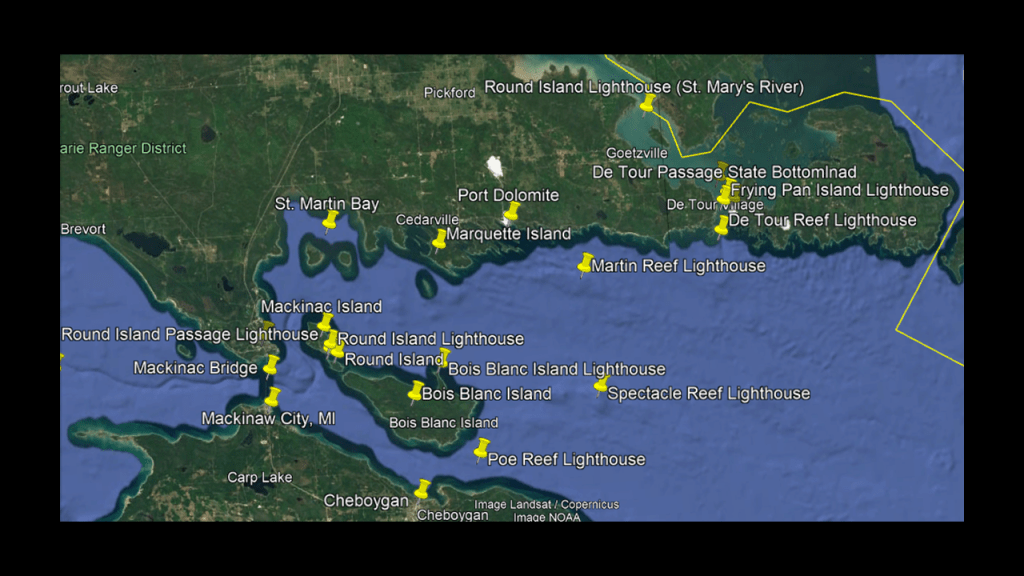

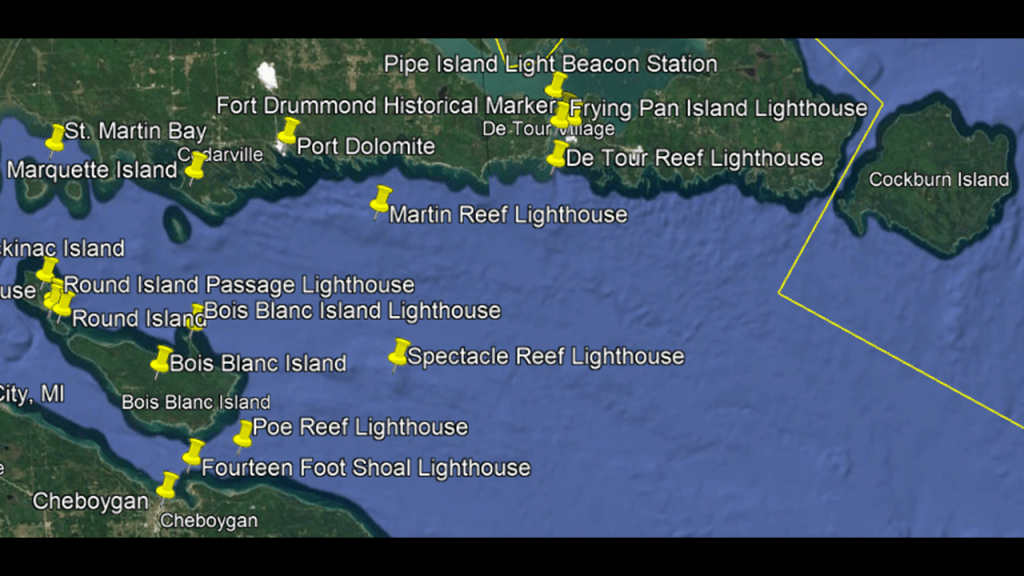

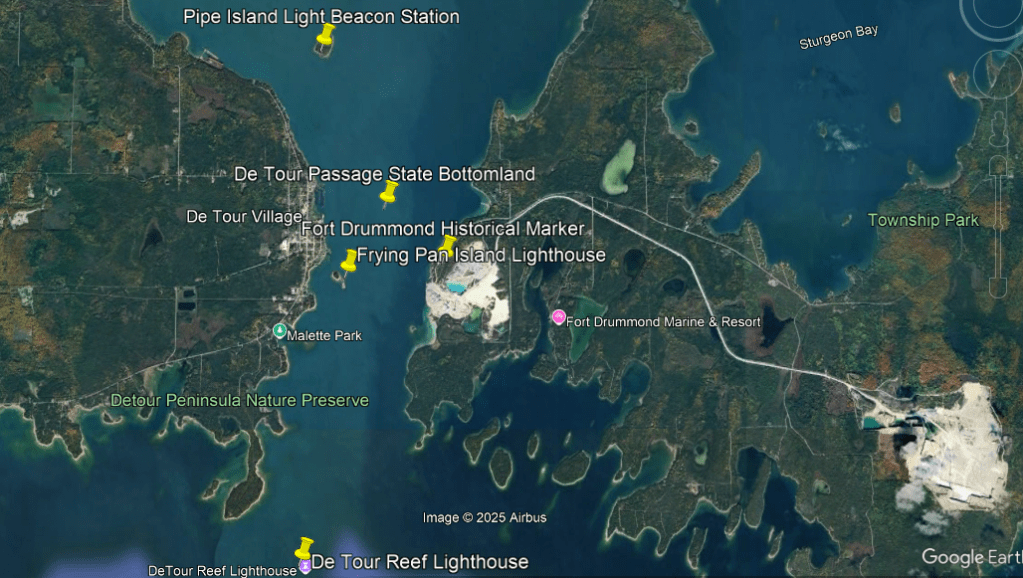

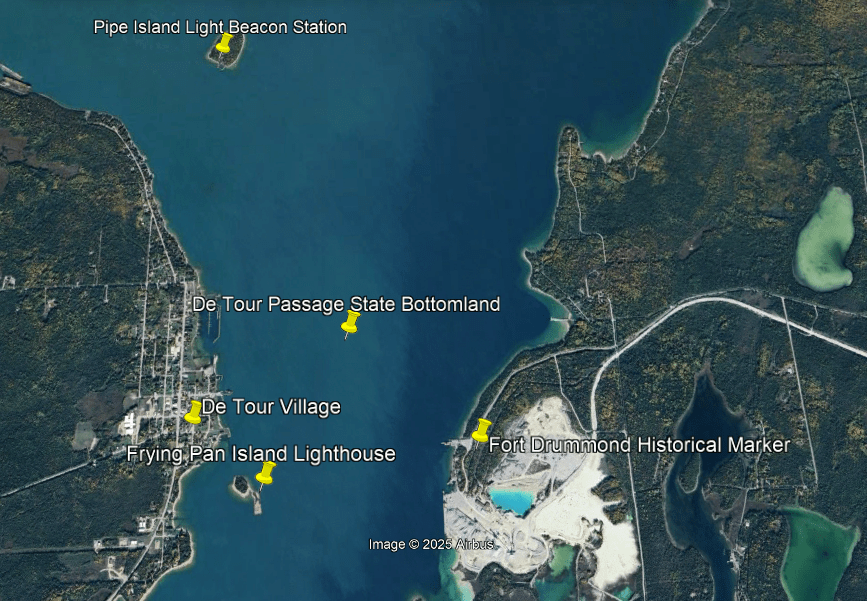

In the part of Lake Huron surrounding these three islands, we find Poe Reef Lighthouse; the Fourteen Foot Lighthouse; the Spectacle Reef Lighthouse; the Martin Reef Lighthouse, and more lighthouses in what is called the De Tour Passage – De Tour Reef Lighthouse; Frying Pan Island; the historical location of Fort Drummond; and the Pipe Island Light Beacon Station.

The Poe Reef Lighthouse is between Bois Blanc Island and the mainland of the Lower Peninsula, 6-miles, or 9.7-kilometers, east of Cheboygan.

Poe Reef is a problem for shipping, lying 8-feet, or almost 2.5-meters, below the surface of the water.

The Poe Reef Lighthouse was said to have been built in 1929, and sits on the northern-side of the South Channel, where the water is too shallow for Lake freighters.

Same story with the Fourteen Foot Shoal Lighthouse on the southern-side of the South Channel, and 3 1/2-miles, or 5.6-kilomters, from the Poe Reef Lighthouse.

It was also said to have been built in 1929 where there was a significant navigational hazard, with the water here being only 14-feet, or almost 4 1/2-meters, -deep.

The Spectacle Reef Lighthouse is on the other side of Bois Blanc Island from the Poe Reef and Fourteen Foot Reef Lighthouses.

The Spectacle Reef Lighthouse is 11-miles, or 18-kilometers, east of the Straits of Mackinac.

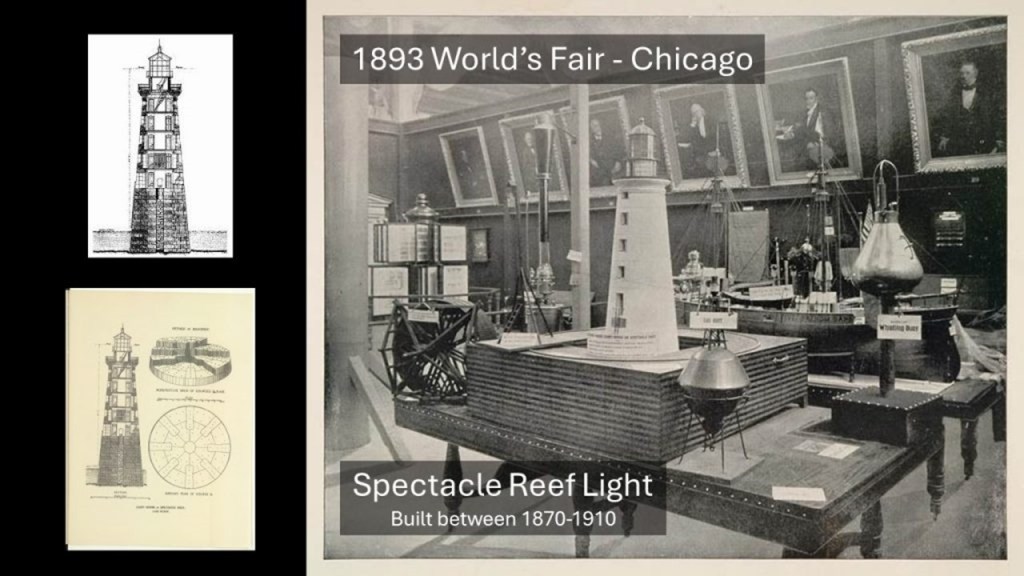

It was said to have been constructed at great expense between 1870 and 1874, and made of interlocking, hand-cut limestone blocks, and is 86-feet, or 26-kilometers, in height.

The Spectacle Reef Lighthouse is at a location where there are two limestone shoals that resemble a pair of eyeglasses, which constituted the most dreaded navigational hazard on the Great Lakes.

What we are told in our historical narrative is that there was an effort between 1870 and 1910 to build lighthouses where there were isolated reefs, shoals, and islands that were significant navigational hazards.

The Martin Reef Lighthouse is at a location where the water of Lake Huron is only a few inches deep in its shallowest area, and another significant hazard.

This lighthouse was said to have been constructed in the summer of 1927.

We are heading in the direction of the De Tour Passage, where we find things like several more lighthouses – De Tour Reef Lighthouse; Frying Pan Island; ; and the Pipe Island Light Beacon Station.

There are some other noteworthy things here as well, like the historical location of Fort Drummond and the De Tour Passage State Bottomlands.

This is where the St. Mary’s River starting at Lake Superior connects to Lake Huron, and where the International border between the United States and Canada winds its way through here.

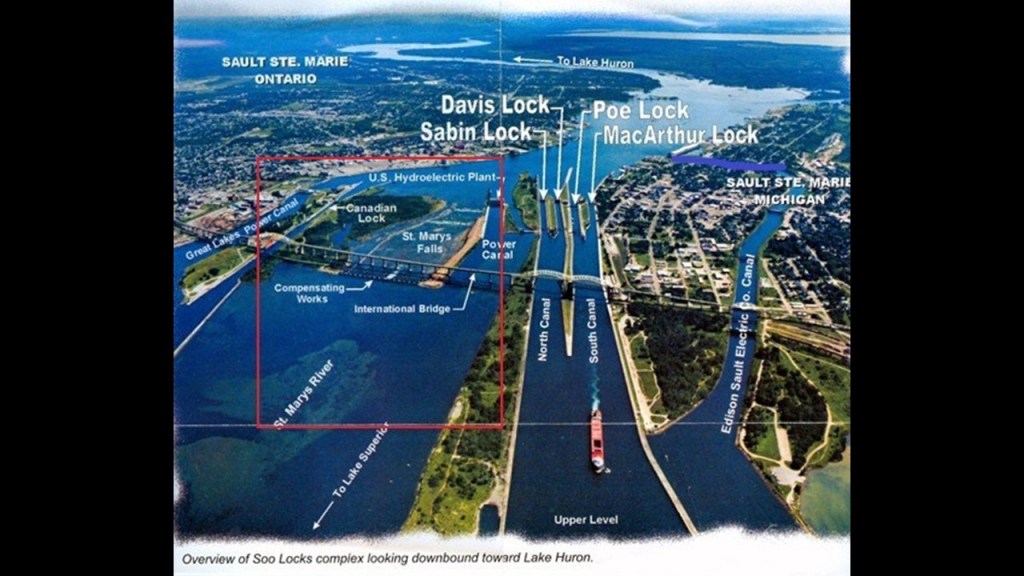

The St. Mary’s River goes through the hydrological powerhouse that is the canal and hydroelectric dam system at Sault St. Marie in Michigan on one-side and in Ontario on the other.

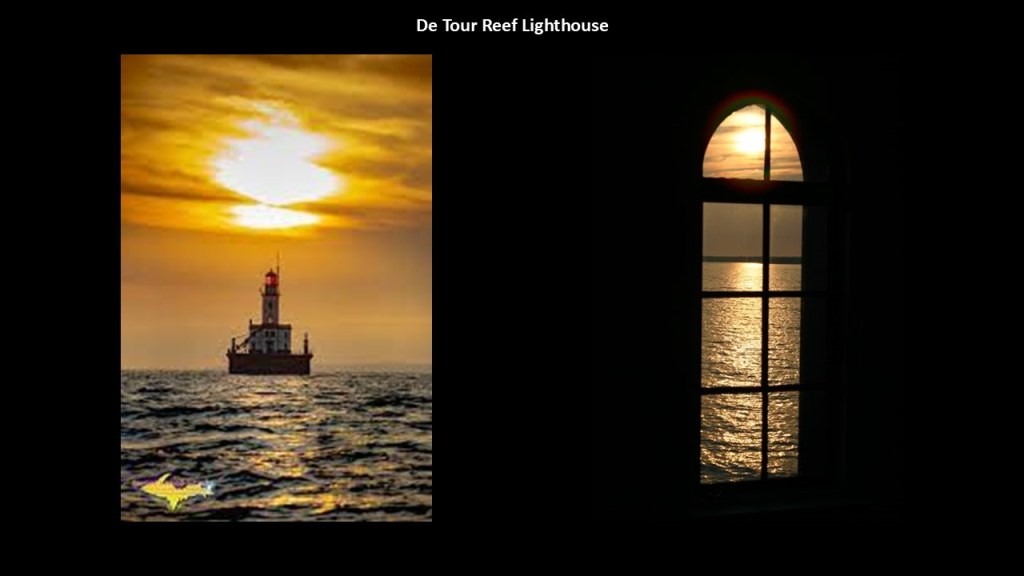

The De Tour Reef Lighthouse is at the entrance of the De Tour Passage on the Lake Huron-side of it.

It is a non-profit-operated lighthouse that it is an important aid to navigation for lake freighters on their way back-and-forth between Lake Huron and Lake Superior.

This lighthouse was said to have been built in 1937, which would have been during the Great Depression, at the location of the De Tour Reef, a dangerous shoal, where vessels must thread there way past a shallow area that is no more than 23-feet, or 7-meters, -deep

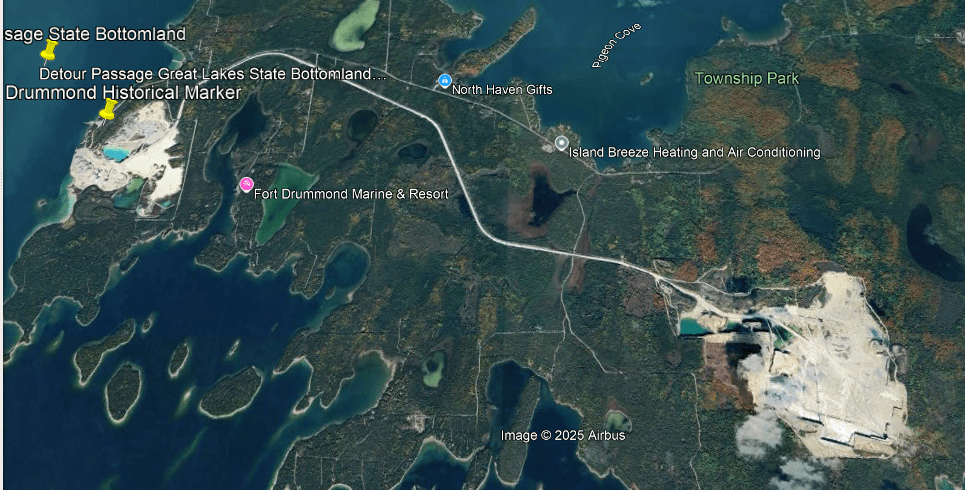

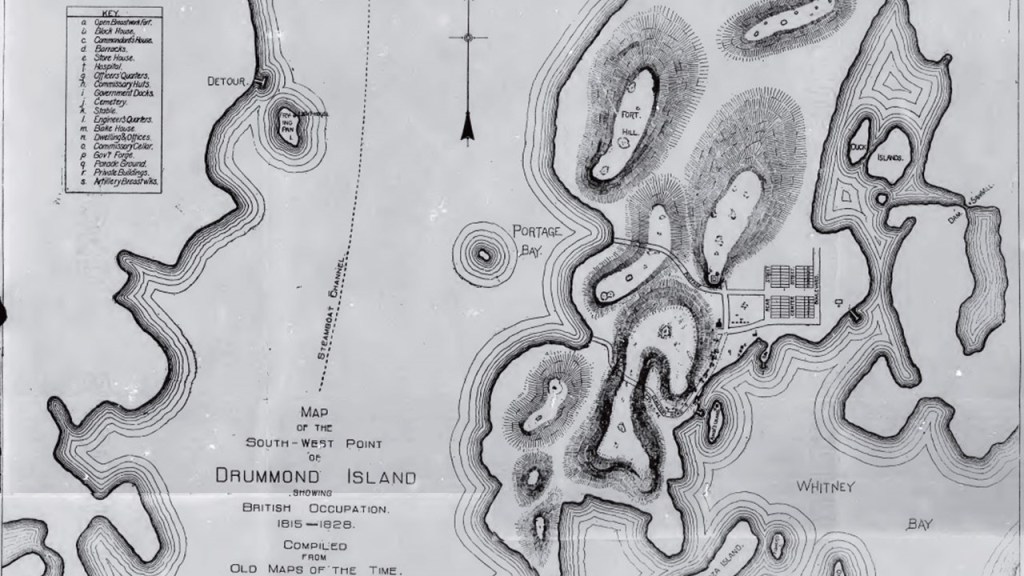

Besides the lighthouses, the De Tour Passage has some interesting activity going on in the vicinity of historic Fort Drummond, and the De Tour Passage State Bottomland.

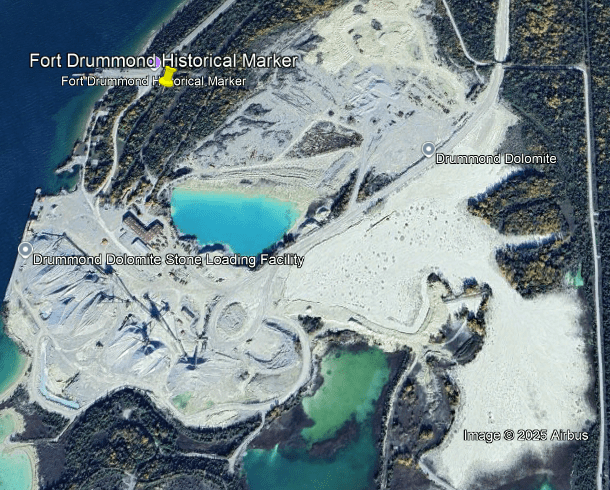

There are two big mining areas showing up in the historical location of Fort Drummond.

A close-up on the mine next to the Fort Drummond Historical Marker shows “Drummond Dolomite.”

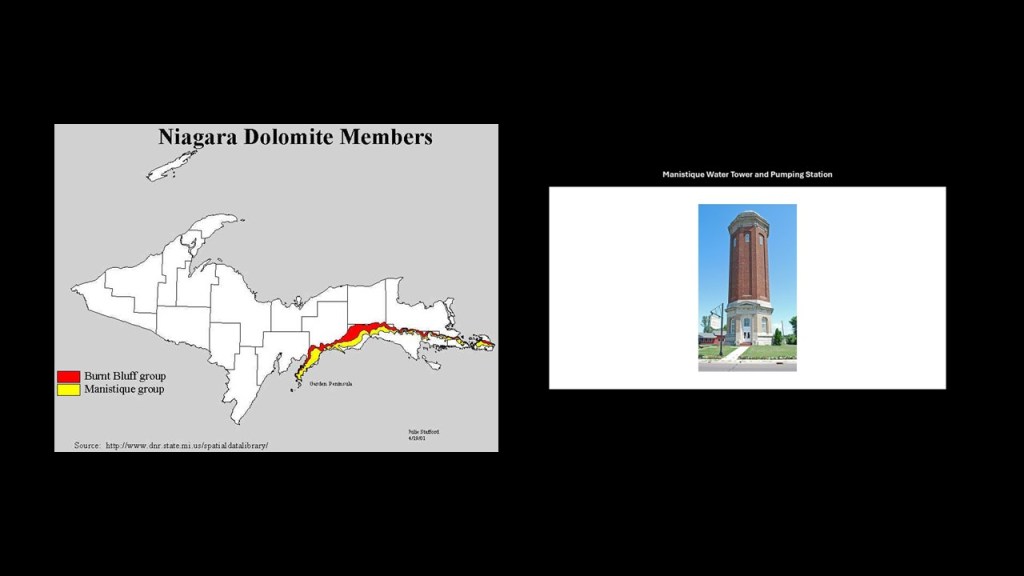

Come to find out that Drummond Island here is part of a vast formation of dolomite on the Niagara Escarpment called the “Engadine Corona,” originating on the eastern tip of Manitoulin Island and extending to Manistique in Michigan’s Upper Peninsula, a place that I talked about towards the end of the first part of the series on Lake Superior.

I will be revisiting Lake Huron and its connection to the Niagara Escarpment later in this post because from the De Tour Passage, I will be making my way down the western shore of the Lower Peninsula of Michigan on Lake Huron and working my way back up to this area when I travel up the eastern side of it in Ontario because the Niagara Escarpment is what separates Lake Huron and Georgian Bay.

The historic Fort Drummond was said to be the only known military and civilian site established by British forces on American soil during the War of 1812.

According to our historical narrative, the United States government demanded that the British abandon the fort in 1828, which they did, and the American forces that took possession of the fort never did anything with it.

This mining of a star fort location got my attention because I have seen it before.

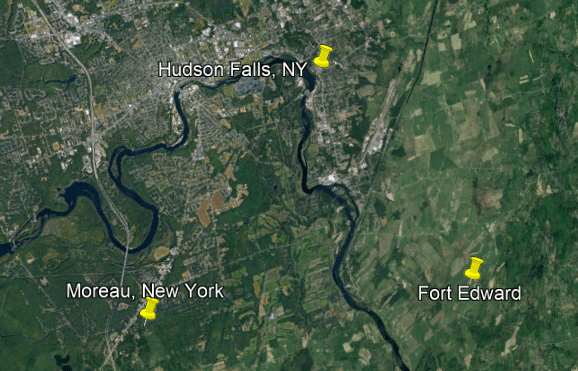

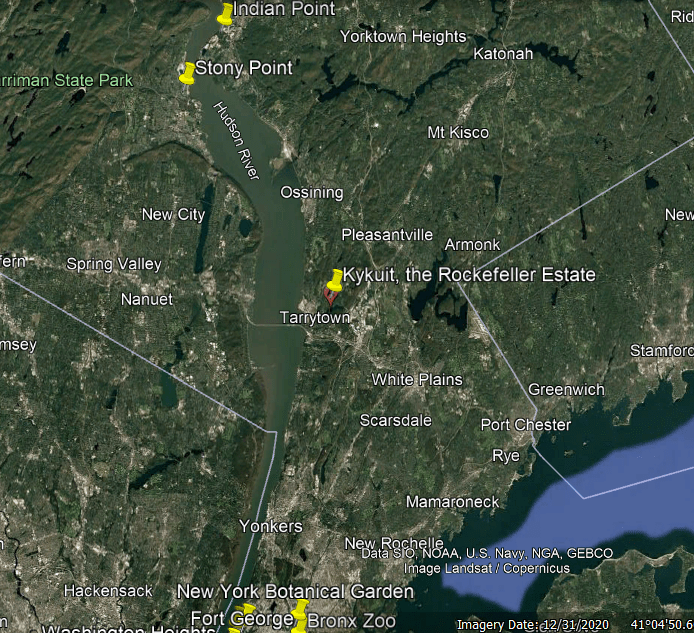

When I was doing the research for “Star Forts, Gone-Bye Trolley Parks and Lighthouses of New York’s Hudson River Valley & New York Bays” back in November of 2022, I encountered several places like this along the way.

One was in Moreau, New York, along the S-shaped bends of the Hudson River, near Hudson Falls and Fort Edwards.

I will be talking more in-depth about the waterfalls of the Great Lakes region in this post as I go around the shores of Lake Huron.

The nearby town of Moreau appears to be an interesting place by just glancing at the Google Earth screenshot.

Moreau has a mined structure next to the Hudson River and the Historical Society that looks like was a star fort at one time.

The towns of Moreau and Hudson Falls are connected by the Fenimore Bridge, which was said to have been constructed in 1906 by the Union Paper and Bag Company as the company had plants in both places.

With fifteen arch spans, roadway, sidewalk and a standard gauge railway track, at one time, it was considered the longest, multiple-span, reinforced concrete arch bridge in the world.

It was closed to traffic in 1989 after it was deemed to be structurally-deficient, and a replacement bridge was built next to it.

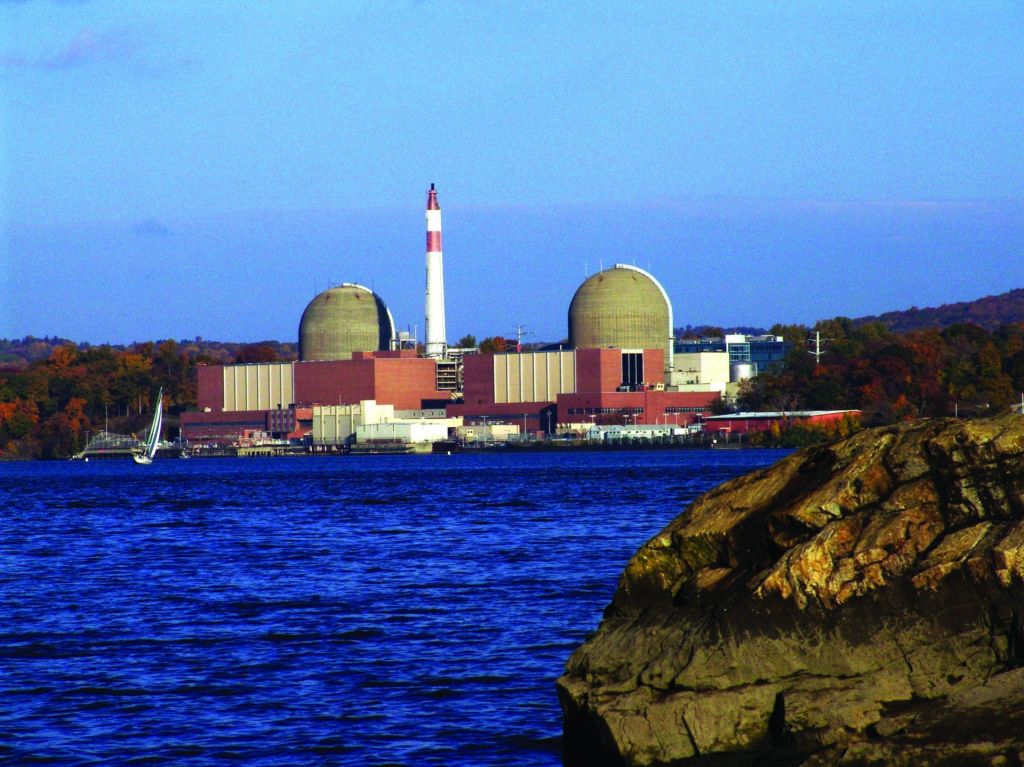

I found another place that was being mined further down the Hudson River that looked like it was a star fort at Tompkins Cove, which is directly across the river from the former Indian Point Park/Nuclear Power Plant and is directly adjacent to the Stony Point Lighthouse.

This is a close-up view of the mining of what appears to have been a star fort at Tompkins Cove, like what is seen in Moreau and Fort Drummond/Drummond Island

Indian Point is directly across from Tompkins Cove.

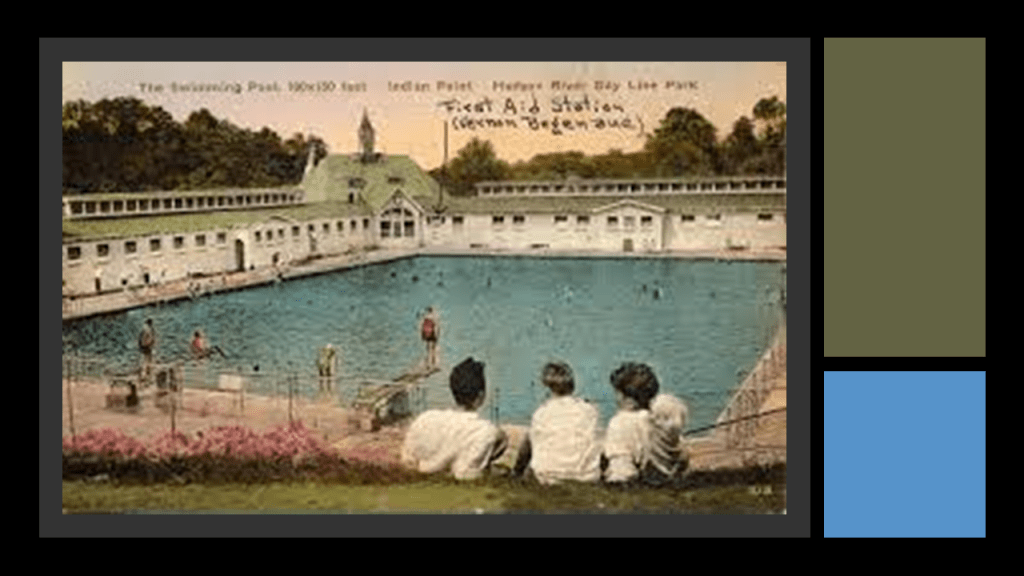

Indian Point Amusement Park was said to have been created in 1923 on a former farm by the Hudson Day Line, the premier steamboat line on the Hudson River from the 1860s through the 1940s, as a recreational park for its passengers.

The Indian Point Park had a cafeteria, picnic facilities, baseball diamonds, rides and games, dance hall, beer hall, miniature golf, swimming pool and speedboat rides.

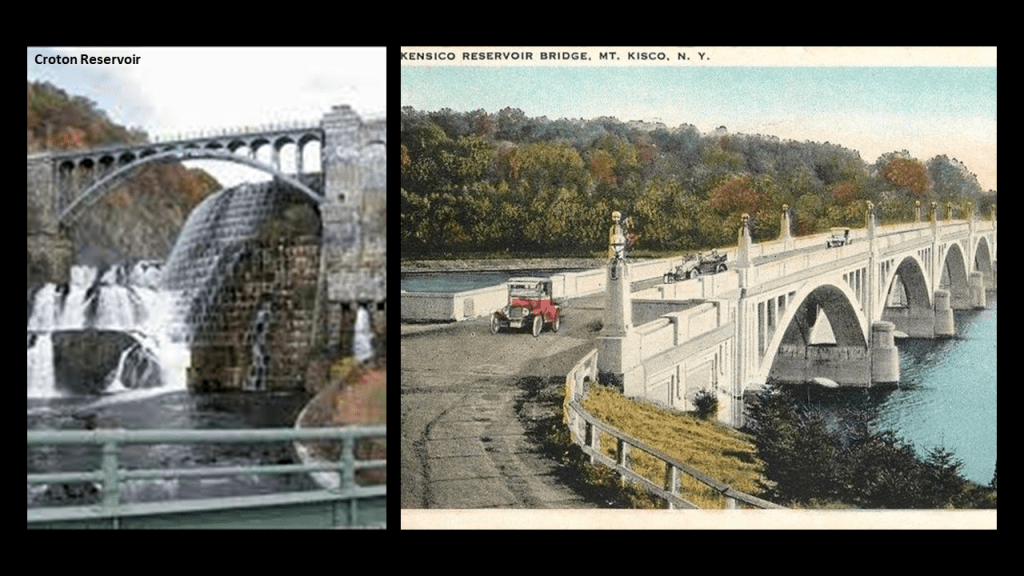

The property backed up to the Croton and Mt. Kisco Reservoirs that provided water to New York City.

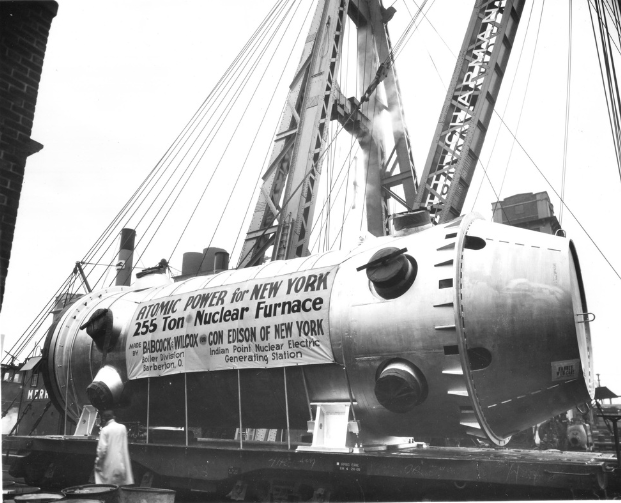

It reopened in 1950 under new management and operated for a few more years until it closed in the mid-1950s and the property was purchased by Consolidated Edison Gas and Electric Company for the Nuclear Power Plant which opened in 1962…

…and which was in operation until April 30th of 2021 when Indian Point Energy Center was permanently closed.

Before its closure, the two reactors there provided an estimated 25% of New York City’s electrical power usage.

The Stony Point Lighthouse is on the same side of the Hudson River as Tompkins Cove, and just below it.

Before leaving the town of Stony Point, there is a light house here to show you.

Like we are seeing with places associated with the War of 1812 taking place at several locations on Lake Huron at the Straits of Mackinac, the Stony Point Lighthouse stands on the grounds of the Stony Point State Historic Site, said to be the location of the 1779 Battle of Stony Point during the American Revolutionary War.

We are told the Stony Point Lighthouse is the oldest lighthouse on the Hudson River, having been built in 1826 to warn ships away from the rocks of the Stony Point peninsula.

It was decommissioned in 1925; acquired by the Parks Commission in 1941, and added to the National Register of Historic Places in 1979; restored starting in 1986, and reactivated in 1995.

Doesn’t this lighthouse look rather strange?

Short and squat…and crooked?

Like maybe this is the top of a much larger structure, the rest of which has been encased in earth?

There is one more thing I would like to mention before I return to Lake Huron and the De Tour Passage from the Hudson River.

There was a massive Rockefeller presence in our historical narrative up-and-down the Hudson River, as well as the New York City area.

The John D. Rockefeller Estate known as “Kykuit” is just down the Hudson River in-between Stony Point and New York City, a word which looks like “Circuit.”

Situated on the highest point in the Pocantino Hills, the Rockefeller Estate was said to have been built in 1913.

I know I digress but I believe these are significant findings with regards to how the original energy grid was constructed, and then it was deliberately destroyed, and reverse-engineered into an energy-harvesting system, and who was behind it all.

In the process of the destruction of the energy grid, the surface of the Earth was destroyed.

Then the components of the energy grid were harvested by those responsible for what has taken place here on Earth without our knowledge or consent, and we find the same kinds of being stories told to cover all of this up, and the same kinds of things are found along the Hudson River in New York that are found in the Great Lakes region…

…including finding John D. Rockefeller in Duluth on Lake Superior.

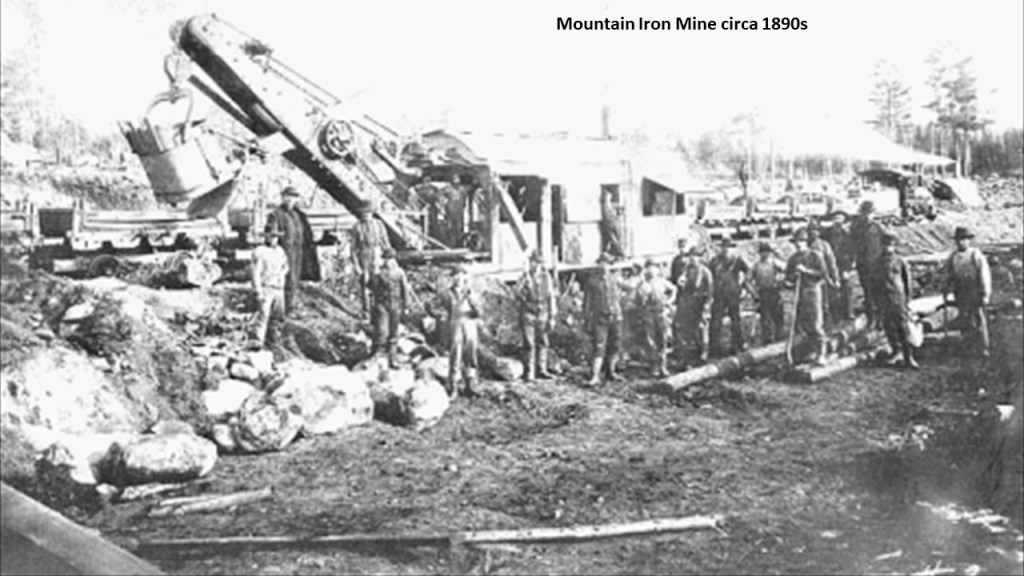

in the 1890s, the Merritt Brothers, also known as the “Seven Iron Brothers” owned the largest iron mine in the world in the 1890s.

We are told that in 1891, the Merritt family incorporated the Duluth, Missabe, and Northern Railway Company to build a 70-mile, or 113-kilometer-long, railroad from the mine to the port at Superior, Wisconsin, which was just to the south of Duluth, raising the money needed in exchange for bonds from the railroad company.

Their success attracted the attention of John D. Rockefeller, who wanted to expand into the iron ore business, and the Merritts put their company stock up as collateral to borrow money from Rockefeller in order to fund the railroad.

Long story short, the Merritts ended up being financially ruined, and Rockefeller came to own both the mine and the railroad.

After Rockefeller assumed ownership in 1894, he leased his iron ore properties and the railroad to the Carnegie Steel Company in 1896.

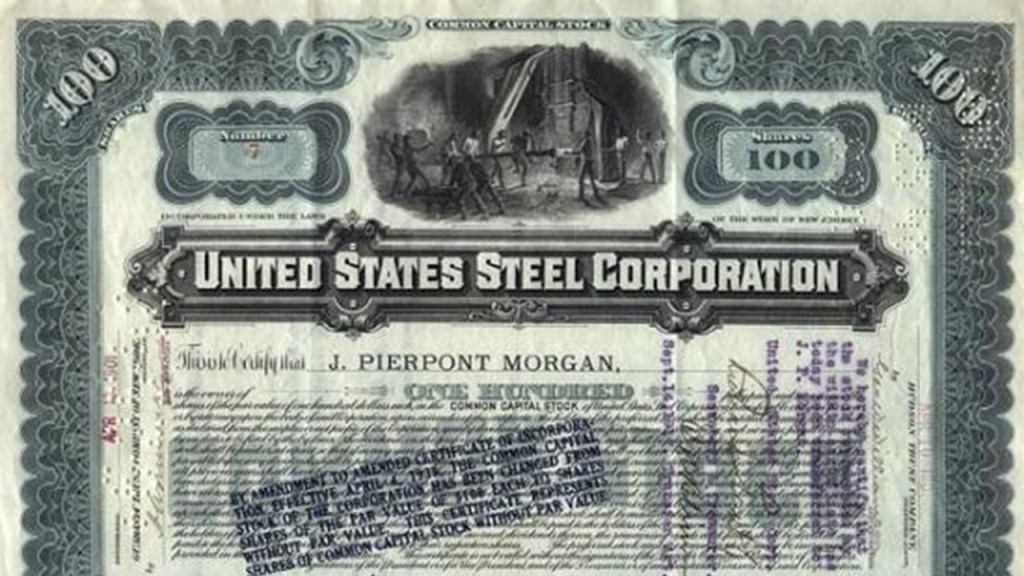

John D. Rockefeller sold the railway to United States Steel in 1901, after it had been formed by the merger of Andrew Carnegie’s Carnegie Steel Company, Elbert Gary’s Federal Steel Company, and William Henry Moore’s National Steel Company in 1901, which was financed by J. P. Morgan.

J. P. Morgan was an American financier and banker who dominated corporate finance on Wall Street throughout the period of time called the “Gilded Age,” between the years of 1870 and 1900.

He was a driving force behind the wave of industrial consolidation in the United States in the late 19th- and early 20th-centuries.

Besides his involvement in the formation of the U. S. Steel Corporation, he was also behind the formation of General Electric and International Harvester, among many other mergers.

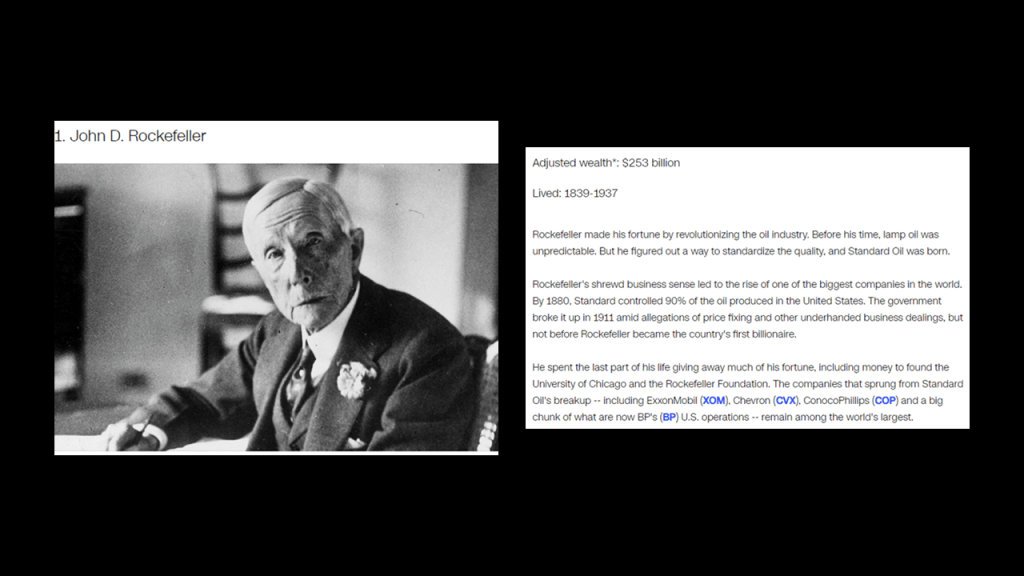

John D. Rockefeller, the progenitor of the wealthy Rockefeller family, is at the top of the list of the Robber Barons behind the reset of our history.

He was considered to be the wealthiest American of all time, as seen in this ranking by CNN Business, with an adjusted wealth of $253-billion.

Rockefeller’s wealth soared as kerosene and gasoline grew in importance.

At his peak, he controlled 90% of all oil.

It is my belief from all my research that as quickly as possible, a way was found to replace what remained of the free-energy system with their own coal- and oil-based system, and in the process make money hand over fist from the total control of the new system.

Now back to the De Tour Passage on the St. Mary’s River where it connects to Lake Huron.

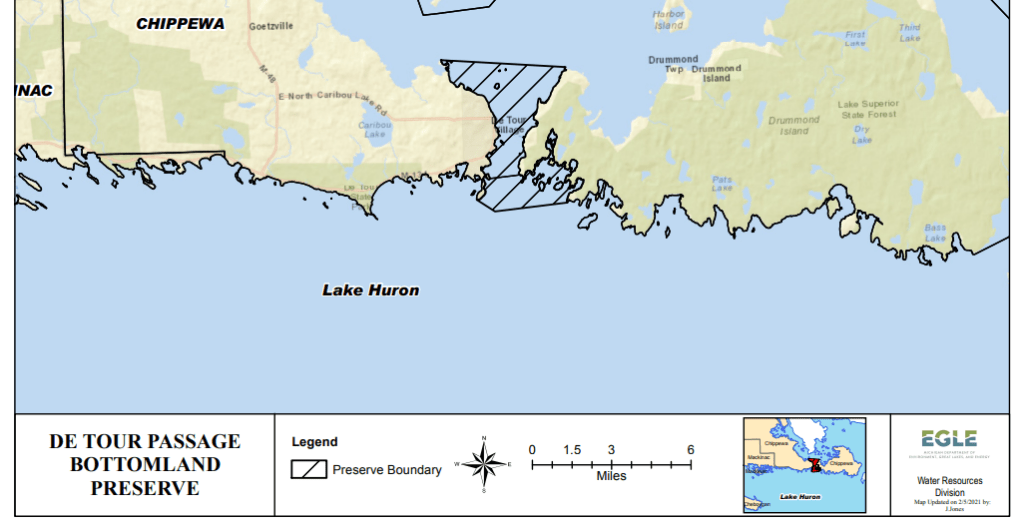

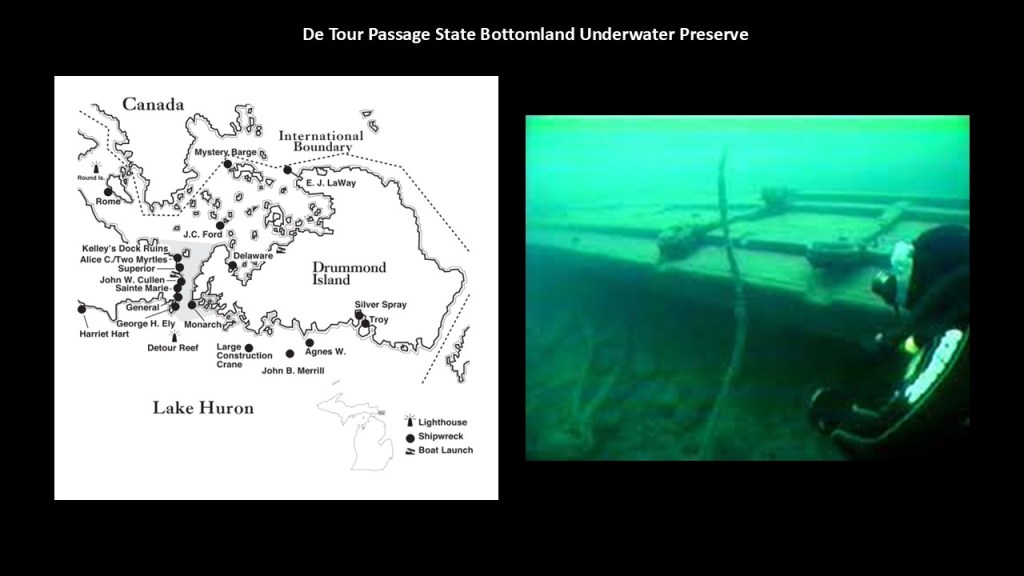

Today’s Pipe Island Light Beacon Station is at the north entrance of the De Tour Passage, and in-between it and the Frying Pan Island Lighthouse is the “De Tour Passage State Bottomland.”

This is what we are told about this location.

The Pipe Island Lighthouse was said to have been established and first lit in 1888 to aid shipping entering into the St. Mary’s River from Lake Huron.

While still an active aid to navigation today, we are told that in 1937, the lantern room was deactivated, and a daymarker added in place of the lantern.

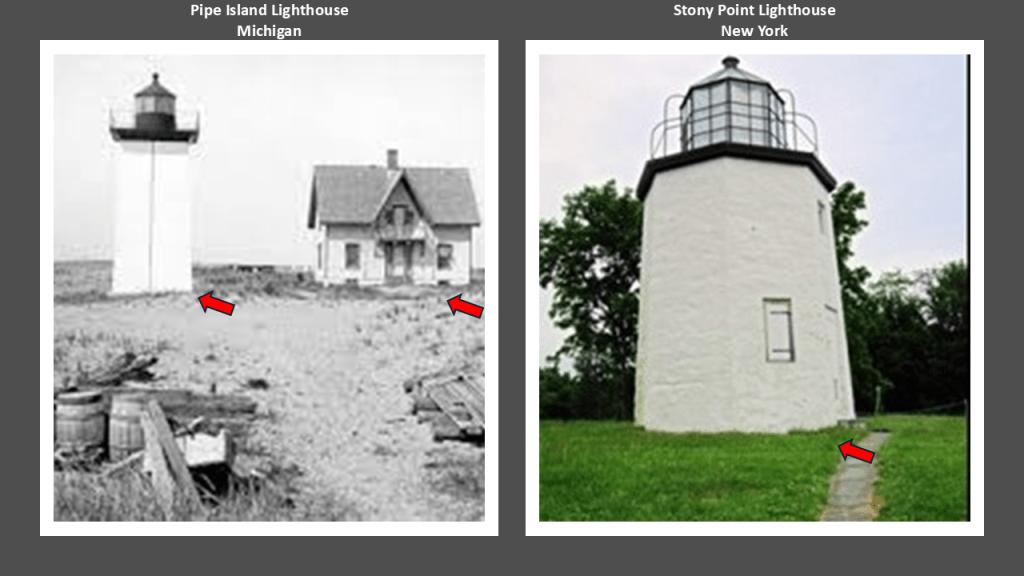

And for comparison of similarity of appearance, here is the same photo of the Pipe Island Lighthouse and a building next to it on the left, and the just shown Stony Point Lighthouse on the Hudson River in New York with both places looking like there is more below the earth’s surface.

The “De Tour Passage State Bottomland” is an underwater preserve located throughout the De Tour Passage.

The shallow waters there contain the remains of lost ships that are accessible to divers.

This is what we are told about the Frying Pan Island Lighthouse.

It was first lit in 1882, and built on Frying Pan Island to warn of the Frying Pan Shoal on the St. Mary’s River.

It was said to be a front range light with the light on Pipe Island.

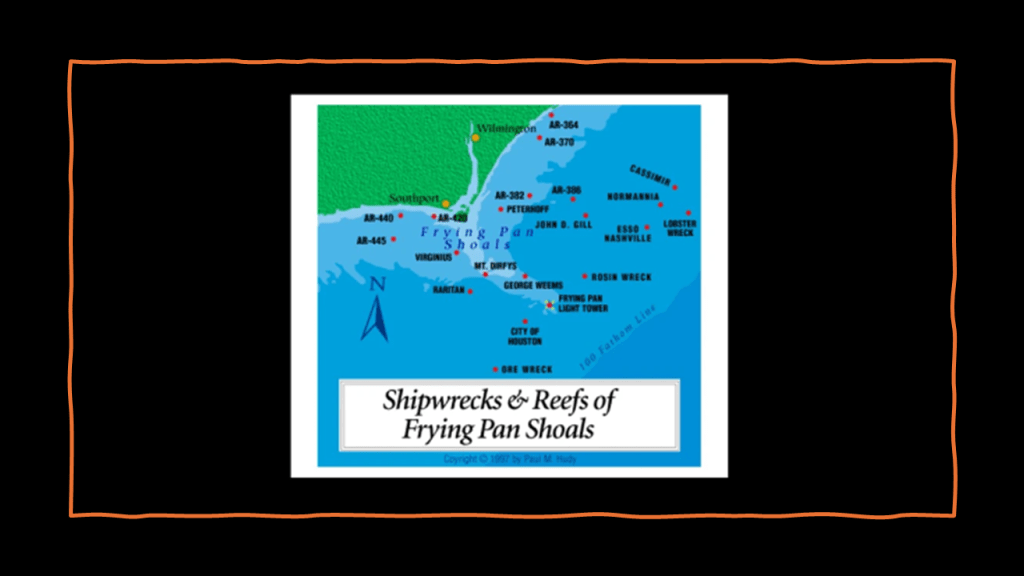

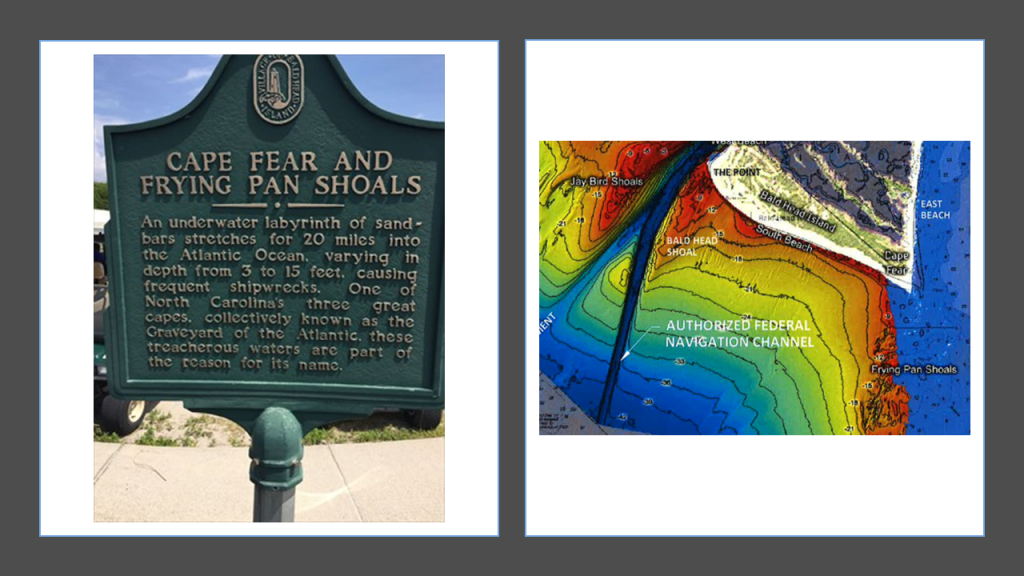

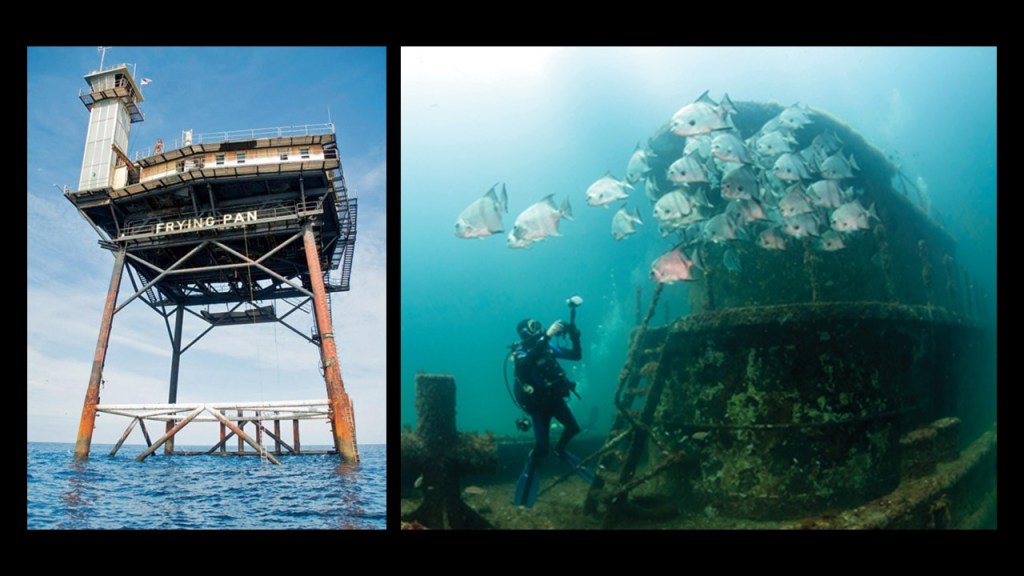

The Frying Pan Island Lighthouse and Shoal in the De Tour Passage brought to my mind the Frying Pan Lighthouse and Shoals in the Cape Fear region of North Carolina, which I found when I was “Trekking the Serpent Ley” from the Bermuda Triangle to Lake Itasca in Minnesota back in August of 2023.

Cape Fear is 5- miles, or 8-kilometers, south at Bald Head Island, and Frying Pan Shoals is the location of many historical shipwrecks.

Frying Pan Shoals is described as a labyrinth of sandbars that extend 20-miles, or 32-kilometers, into the Atlantic Ocean, and is known as the “Graveyard of the Atlantic.”

Frying Pan Tower & Light Station is also now a Bed & Breakfast, and also a popular destination for scuba divers to check out the wrecks.

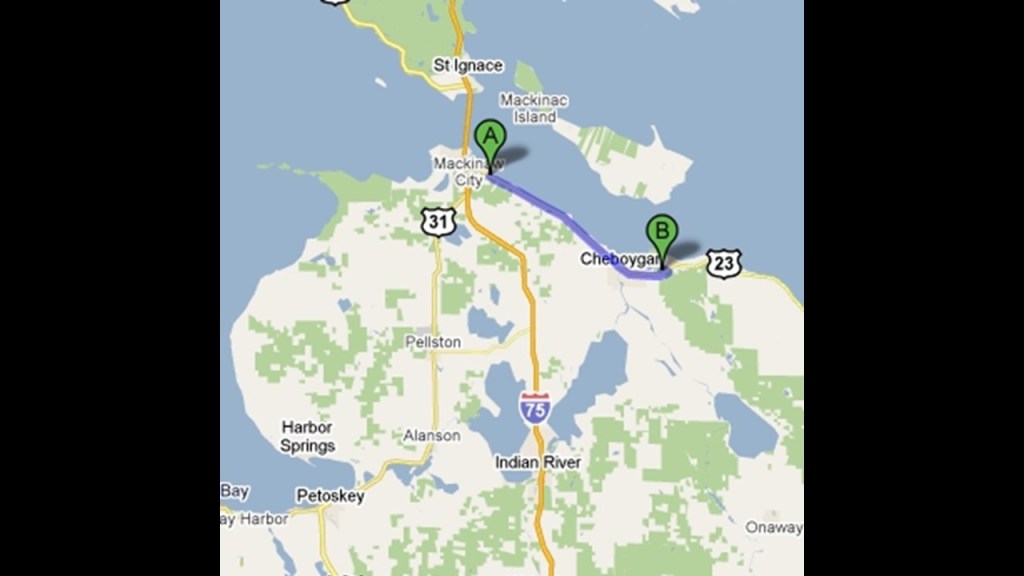

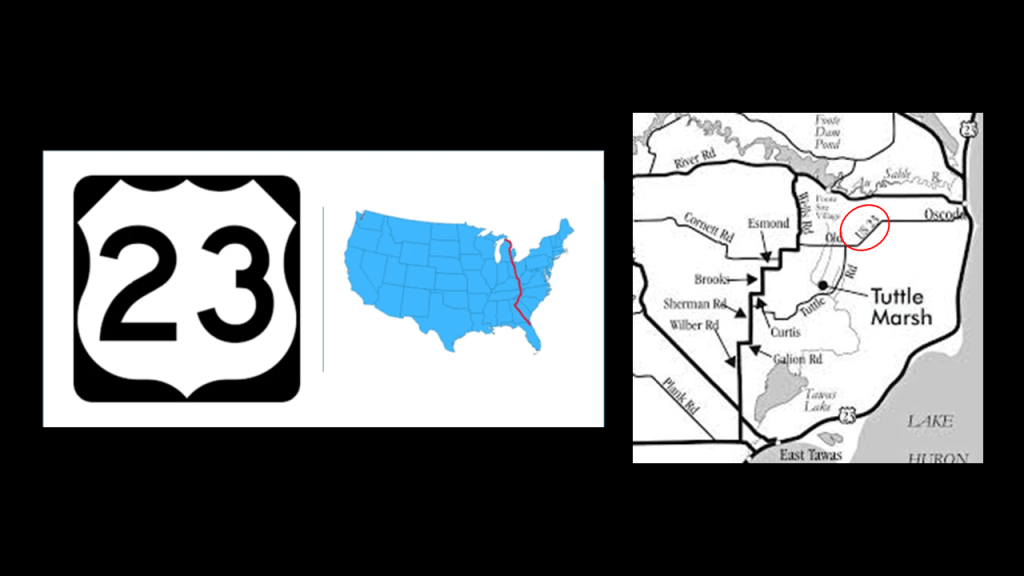

Now I am going to turn my attention to Cheboygan located a short-distance to the southeast of Mackinaw City on US Highway Route 23, and start the journey from the top of the mitten of Michigan’s Lower Peninsula down the western-side of Lake Huron.

Before I look around to see what’s available to find in Cheboygan, upon seeing the presence of US Highway Route 23 here it’s important for me to take a moment to highlight some of the different aspects about US-23, a subject I brought up in the first part of this series on Lake Superior, and its going to lead me to making a bigger picture connection between highways, waterfalls, railroads, and the original energy grid that will continue to be highlighted in this journey around Lake Huron.

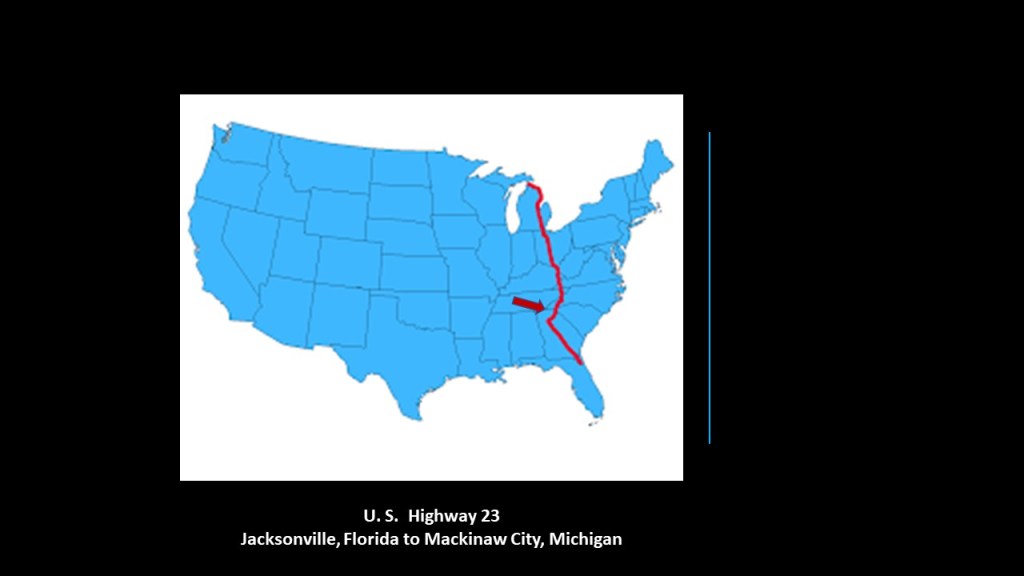

Firstly, US -23 runs for a distance of 1,453-miles, or 2,310-kilometers, between Mackinaw City in Michigan at its northern terminus at I-75, and the southern terminus at the Junction of US-1 and US-17 in Jacksonville in Florida.

Mackinaw City is just a short-distance south on I-75 from St. Ignace across the Mackinac Bridge, which is the northern terminus of I-75.

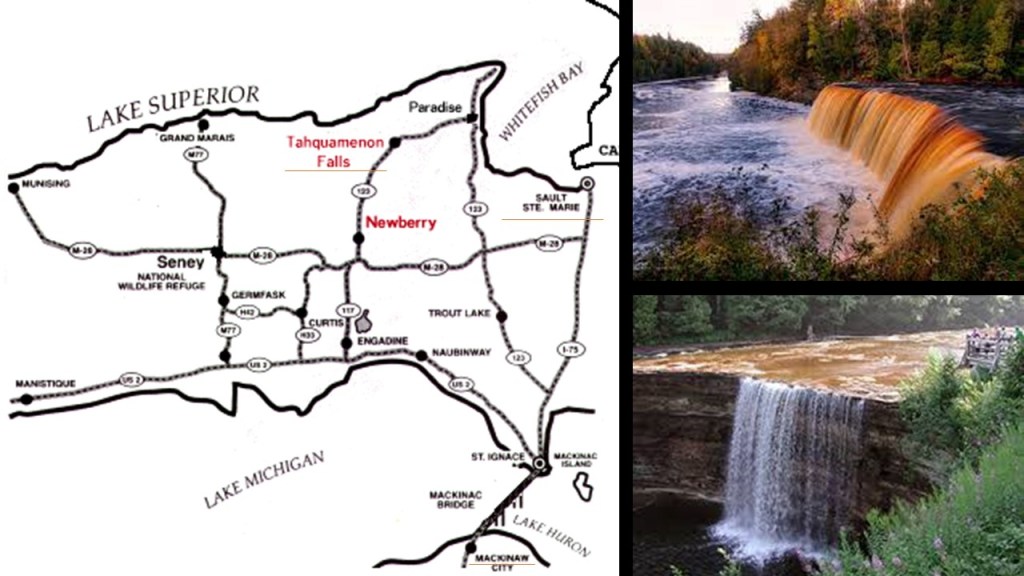

Mackinaw City is not far from the location of the Tahquamenon Falls State Park, where there are a series of waterfalls on the Tahquamenon River before it empties into Lake Superior in the northeastern part of the Upper Peninsula of Michigan, and the Tahquamenon Falls.

The Tahquamenon Falls are on Michigan State Highway 123, and are accessible from Michigan Highway 28.

I was able to find an historical rail presence at Tahquamenon Falls when I searched and what came up was the “Tahquamenon Falls Riverboat Tours & Toonerville Trolley.”

It is a 6 1/2-hour wilderness tour that starts at Soo Junction that includes a narrow-gauge train ride and riverboat cruise to the Falls.

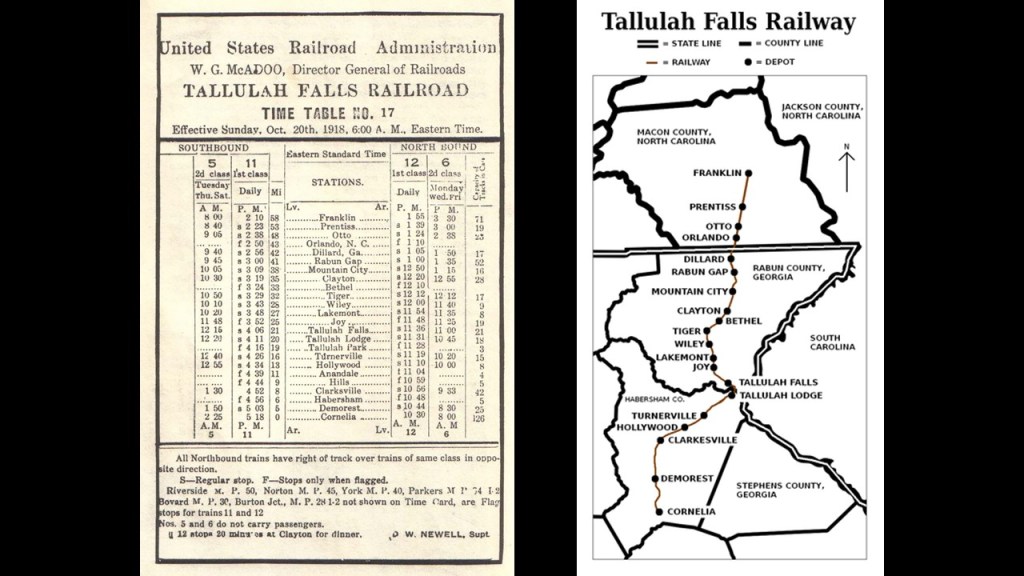

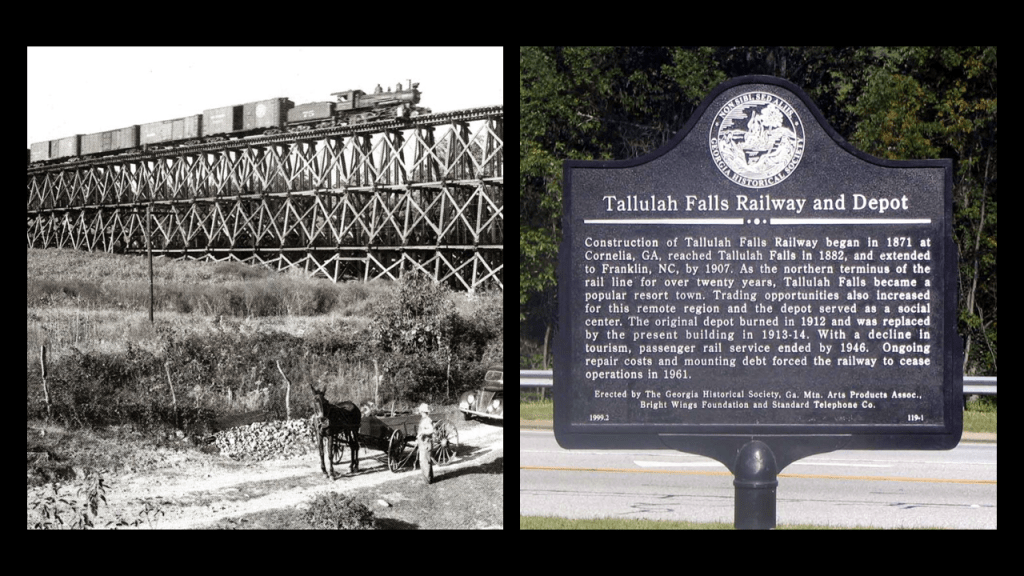

I found this information from past research about the Tahquamenon Falls and Toonerville Trolley because I was looking at the Tallulah Gorge and Falls in Georgia, which are also on US-23.

This was when I was doing the research for “Of Railroads and Waterfalls, and Other Physical Infrastructure of the Earth’s Grid System” back in June of 2023.

The Tallulah Gorge and Tallulah Falls in North Georgia are close to the South Carolina State Line.

A State Park since 1993, the major attractions of the park are the 1,000-foot, or 300-meter, deep Tallulah Gorge; the Tallulah River which runs through the gorge; and six major waterfalls known as the Tallulah Falls which cause the river to drop 500-feet, or 152-meters, over one-mile, or 1.6-kilometers.

This is what we are told.

In 1854, The General Assembly of the State of Georgia first enacted legislation for the construction of a railroad linking the towns of Athens and Clayton in North Georgia, and the railroad opened in sections starting in 1870, with construction of the railroad having been delayed with the outbreak of the Civil War between 1861 and 1865.

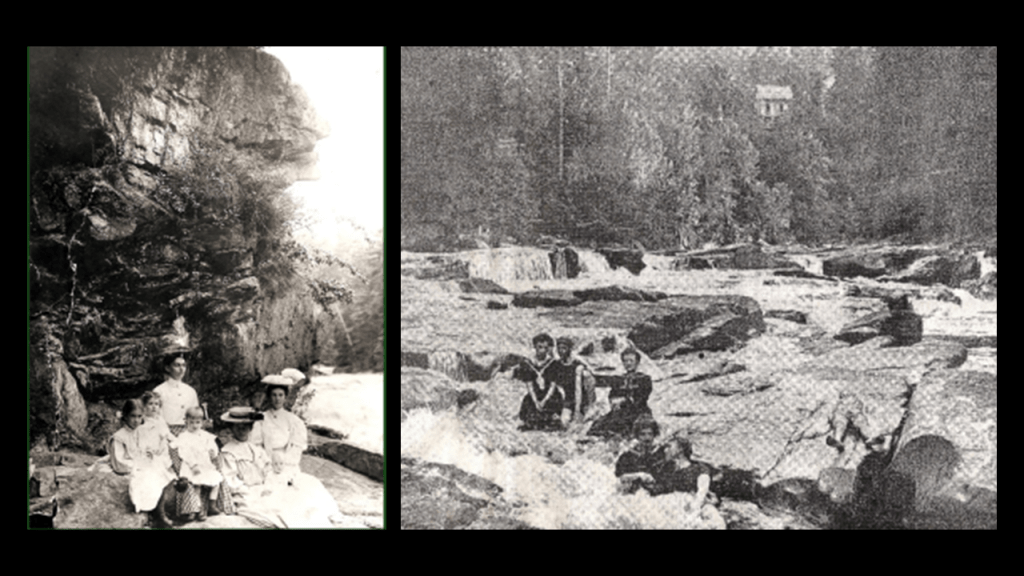

When the railroad arrived at Tallulah Falls in 1882, tourism to the area intensified, bringing thousands of people a week to the area.

At one time, there were seventeen restaurants and boarding houses here catering to wealthy tourists.

Places like the Tallulah Lodge, said to be the grandest lodge at Tallulah Falls with over 100-rooms and built in the 1890s, and located one-mile, or 1.6-kilometers, south of the depot on the rim of the gorge.

The Tallulah Lodge burned down in 1916.

Then there was an historical fire in Tallulah Falls in 1921 that wiped out almost the entire town.

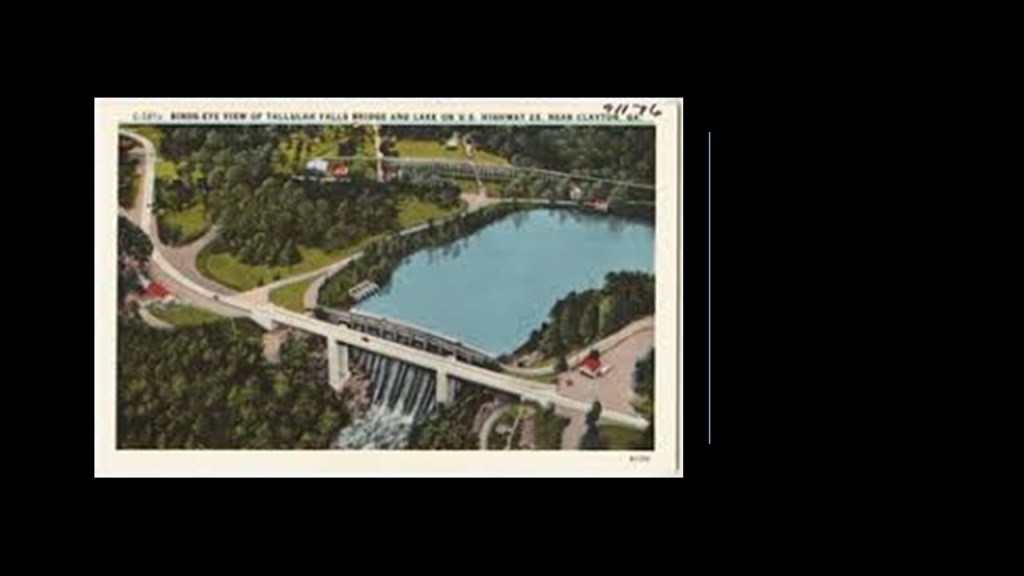

We are told that starting in 1909, the Georgia Railway and Power Company, had scouted the Tallulah River and Gorge with its drop in elevation as the ideal place to construct a dam and hydroelectric plant in order to provide electrical power to Atlanta, and that it ended up being one of six being constructed along a 26-mile, or 42-kilometer, stretch of the Tallulah and Tugaloo Rivers with a 1,200-foot, or 366-meter, drop in elevation, between 1913 and 1927.

The construction of the dam at Tallulah Falls was said to have started in 1910 with the purchase of land at the rim of the Tallulah Gorge, and completed in 1914 after the company won a legal battle to halt its activities in the Tallulah Gorge.

Here is a postcard with the Tallulah Falls Bridge on U. S. Highway 23/State Road 15 crossing right in front of the dam and the Lake Tallulah Reservoir.

The bridge was said to have been built between 1938 and 1939.

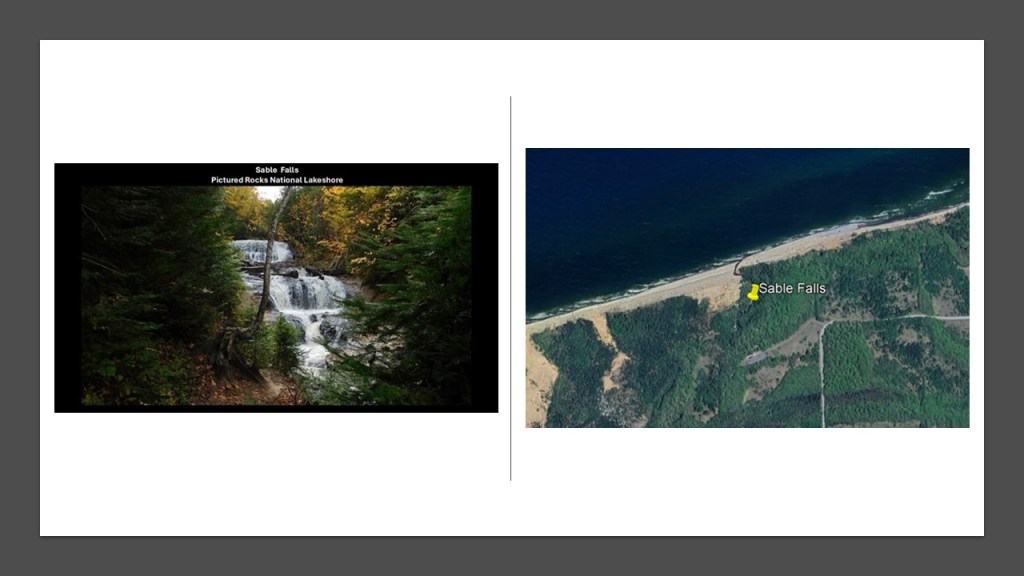

When I was looking at the shores of Lake Superior in the first part of this series, I found the Sable Falls at the northeastern end of the Pictured Rocks National Lakeshore in Michigan.

Sable Falls flow 75-feet, or 23-meters, over what is called Munising and Jacobsville sandstone formations, directly into Lake Superior.

As we go through the information available to find along the way, I will show you exactly why I believe the outflow of the waterfalls of the Great Lakes Region, which were components of a highly-sophisticated hydrological and electrical system throughout the region, as pointed out by the example of the hydrological powerhouse that is the canal and hydrolectric dam system at Sault St. Marie on the St. Mary’s River that connects Lake Superior and Lake Huron, formed the Great Lakes after a deliberately caused cataclysm destroyed the original energy grid and subsequently destroyed the surface of the Earth.

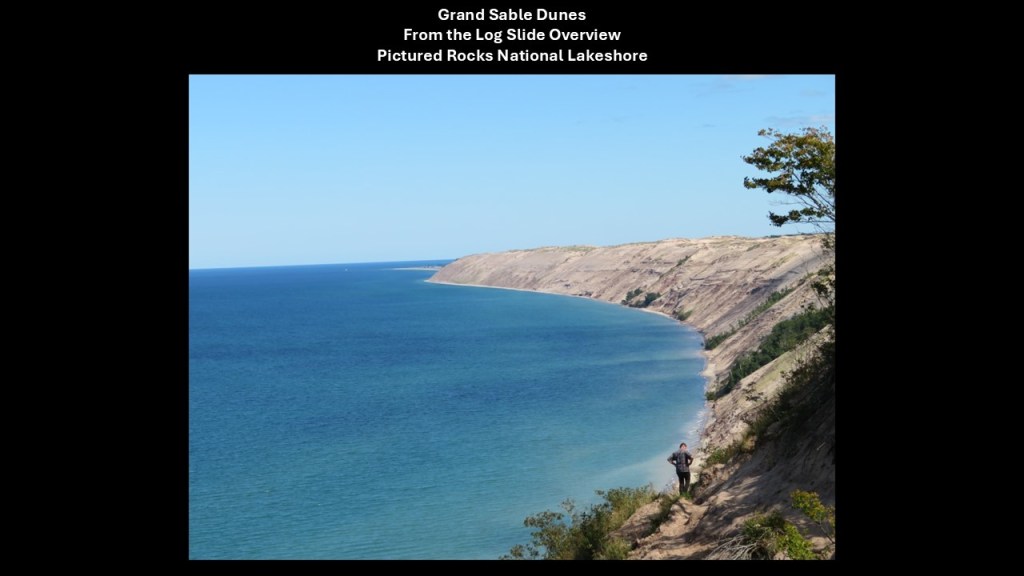

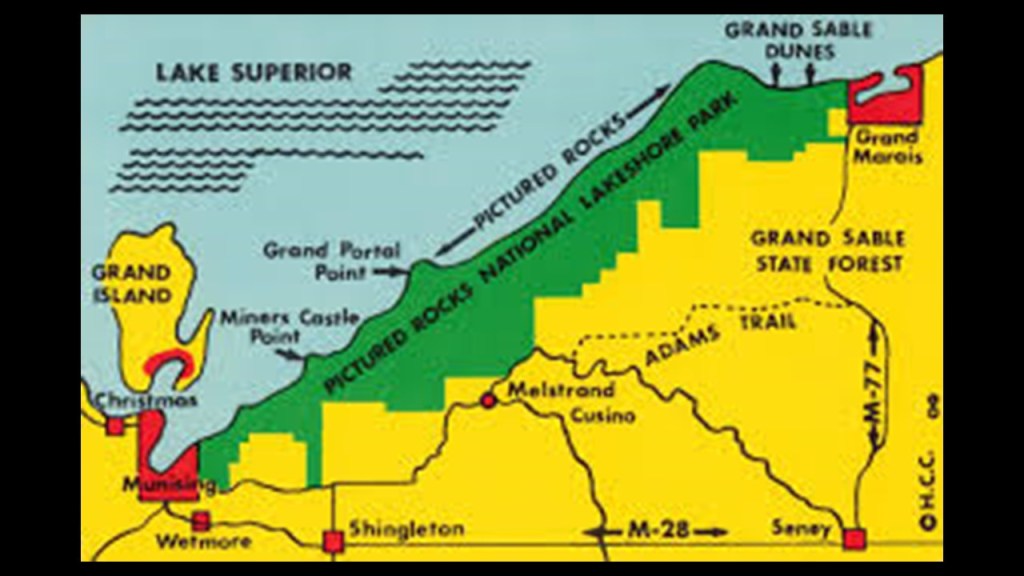

Also in the location of Sable Falls, we find the Grand Sable Dunes running along the northeast end of the Pictured Rocks Lakeshore for 6-miles, or 10-kilometers.

This is the view of them from what is called the “Log Slide Overview,” where in the 19th-century, loggers used them to slide logs from the top of the dunes to the shoreline so they could be transported out.

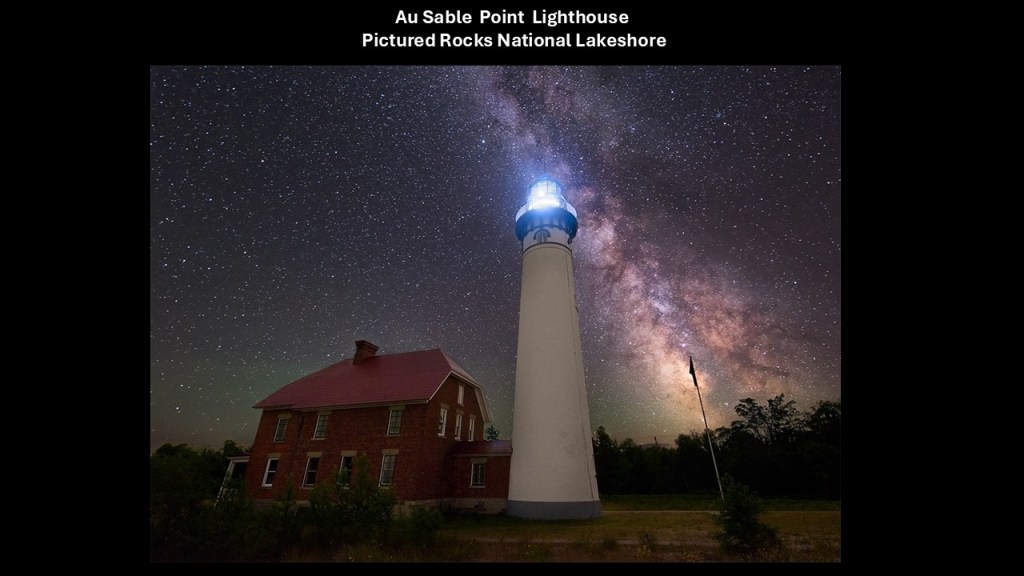

The Au Sable Point Lighthouse is located in the area of the Grand Sable Dunes and Sable Falls, and it is nicknamed the “Beacon of the Shipwreck Coast.”

The lighthouse here was said to have been built between 1873 and 1874.

Munising at the southwestern end of the Pictured Rocks National Lakeshore Park.

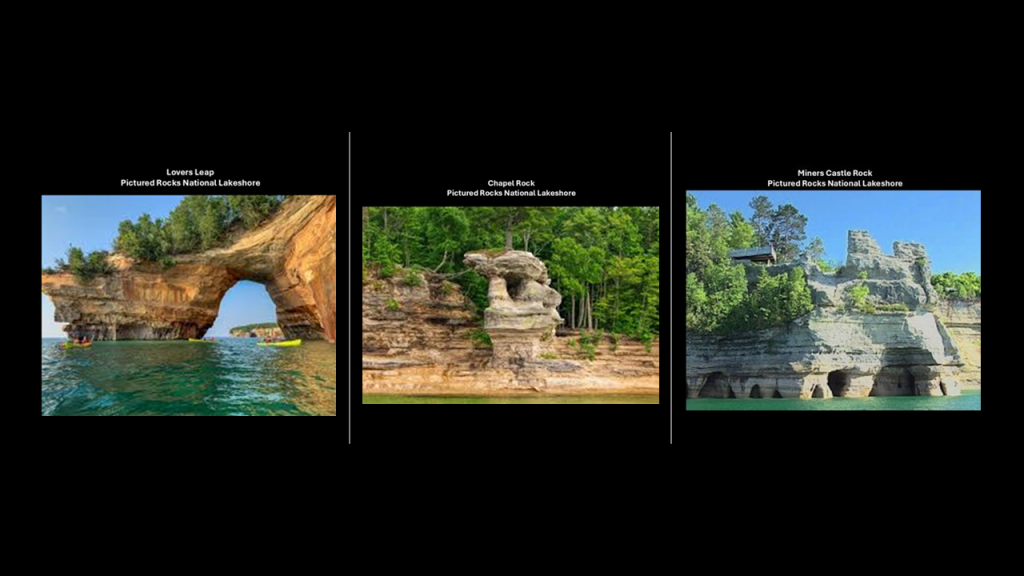

The “Pictured Rocks” are described as dramatic, multicolored cliffs with unusual sandstone formations, but look strangely like melted or ruined infrastructure.

Formations like what are called natural archways all along the lakeshore, like the one called “Lovers Leap” on the left; and unusual formations like the one named “Chapel Rock” in the middle; and Miners Castle Rock” on the right.

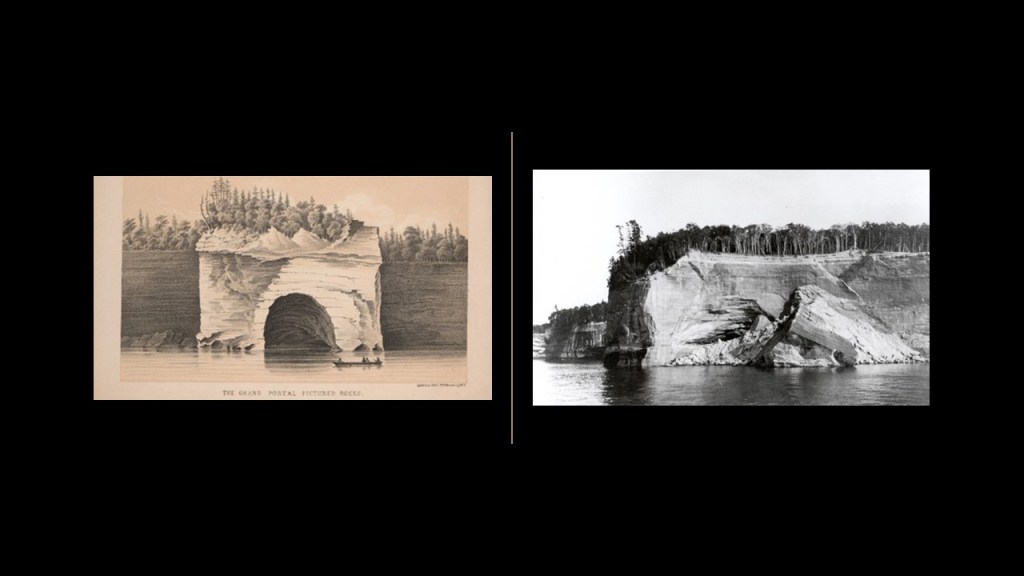

This was Grand Portal Rock as seen in this lithograph from 1851,which mysteriously collapsed in the early 1900s, from the believed cause of erosion but, as the story goes, no one really knows what might have caused it.

Besides Sable Falls, the general area around Munising has many waterfalls.

Others waterfalls in the area include: Alger Falls; Horseshoe Falls; Memorial Falls; Munising Falls; Miners Falls; Scott Falls; Tannery Falls; and Wagner Falls.

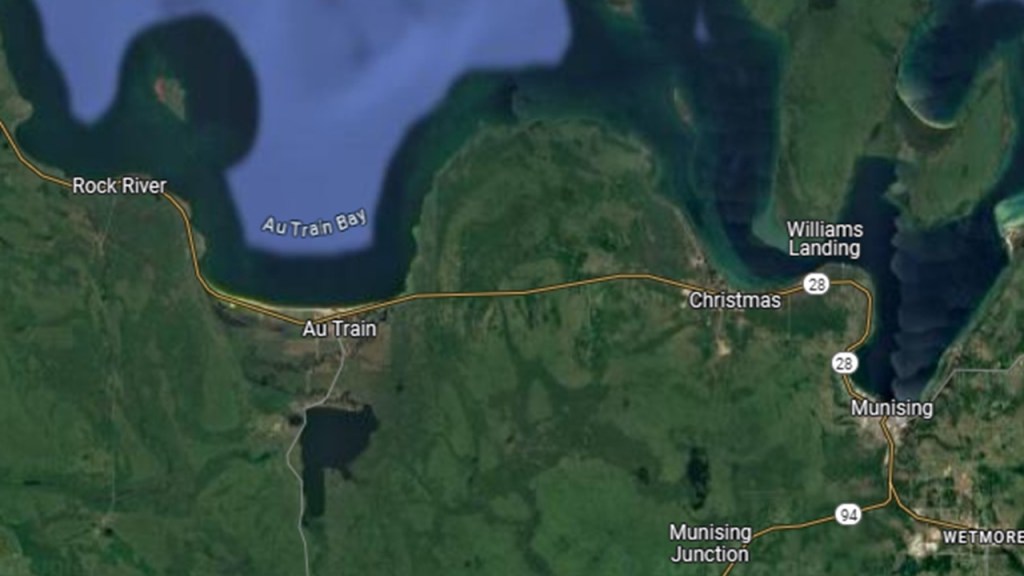

The Munising area is also where Au Train is located.

This information connects back to the Au Train – Whitefish Channel in the Little Bay de Noc of Green Bay I mentioned previously in this post that appears to be an underwater canal.

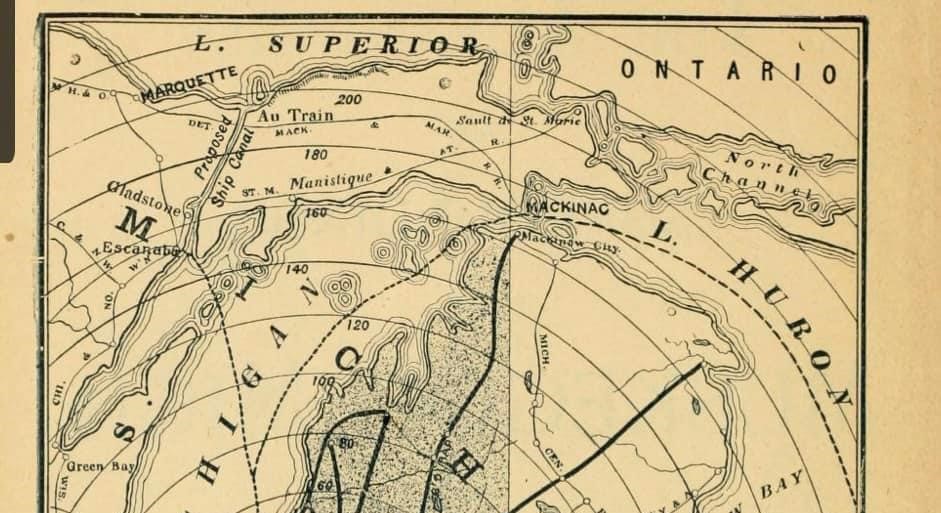

I was able to find a map and reference on-line about there being a proposed ship canal on land in Michigan historically between at Au Train Bay near Munising, and Escanaba at Little Bay de Noc, and we are told that even as recently as the 1980s has been looked into as a possible project for excavation but has been rejected because of projected costs.

Now back to Cheboygan.

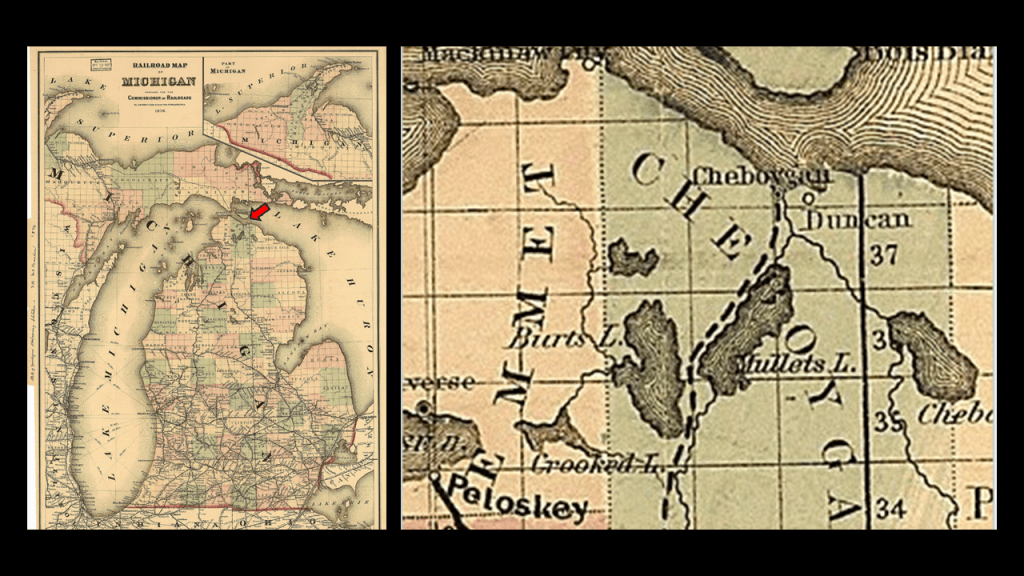

We are told Cheboygan was originally an Ojibwe settlement, and that in 1844 a barrel-maker from Fort Mackinac named Jacob Sammons chose the old native camping ground as a site for his cabin.

He started a settlement here with others and it was named Duncan, sawmills were established in a region known for its lumber, and by 1853, Duncan was the county seat, and by 1870, Duncan was included in the expanded boundaries of Cheboygan, which became the county seat of Cheboygan County.

The City of Cheboygan was incorporated in 1889.

In our historical narrative, the railroad finally came to Cheboygan in 1881 when the Jackson, Lansing and Saginaw Branch of the Michigan Central Railroad extended a railroad line from Gaylord to Cheboygan, which was extended to Mackinaw City the following year.

Then in 1904, the Detroit and Mackinac Railway extended its line to Cheboygan.

As time went on, the lumber industry no longer dominated the economy, though there was a Proctor and Gamble plant here, but when it closed in the 1990s, we are told the need for rail service was eliminated, and today, the former railroads of northern Michigan are considered one of the finest recreational trail systems in the United States, with Cheboygan at the junction of the previously-mentioned North Central State Trail from Gaylord, and the North Eastern State Trail from Alpena.

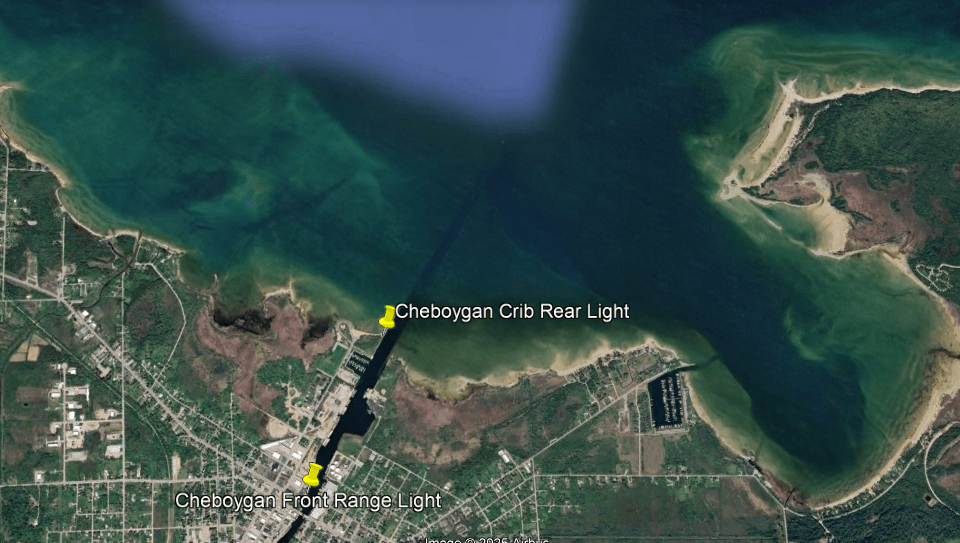

There are two lighthouses in Cheboygan – the Cheboygan Crib Rear Lighthouse and the Cheboygan River Front Range Lighthouse.

The Cheboygan Crib Rear Lighthouse marks the west pier head of the mouth of the Cheboygan River

We are told it was originally constructed in 1884 on what was called a “crib,” which was an artificial-island landfill located more than 2,000-feet, or 610-meters, from the Cheboygan shore, but that in 1984 it was moved to the pier after it was deemed “surplus” property by the Coast Guard

With regards to the Cheboygan River Front Range Lighthouse in our historical narrative, we are told that in 1871, an improvement project to improve the Cheboygan Harbor began by dredging the Cheboygan River, and that by 1883, the portion of the river between the steamboat landing and the railroad dock had been dredged to a width of 200-feet, or 61-meters, and a depth of not less than 14-feet, or 4-meters.

Prior to this, the water over the bar at the mouth of the river had a depth of 7-feet, or 2-meters.

We are told that by 1880, two range lighthouses were operational, one of them being Cheboygan River Front Range Lighthouse, which still stands today.

The other range light was said to have been replaced by a 75-foot, or 23-meter, tall iron tower in 1900.

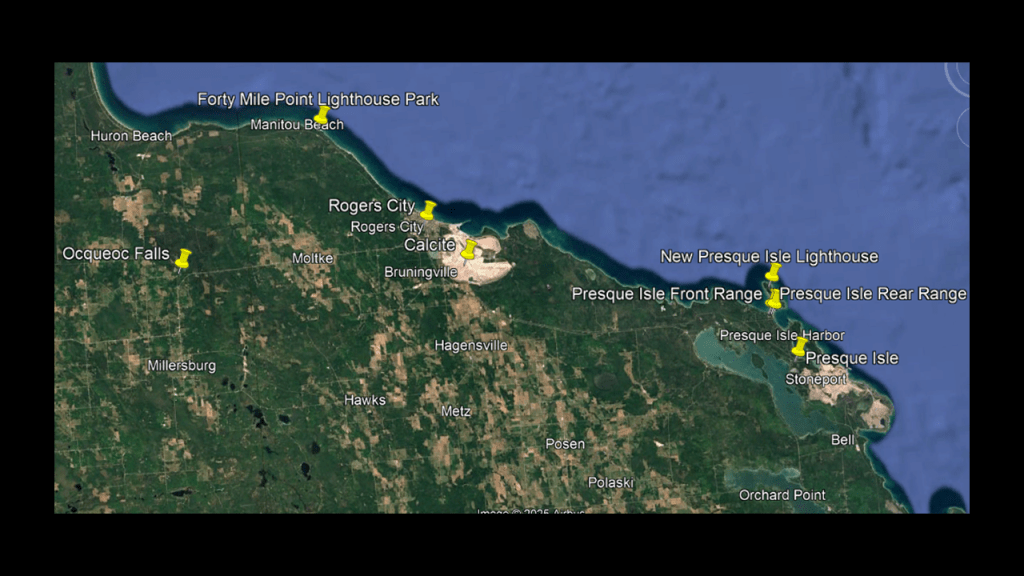

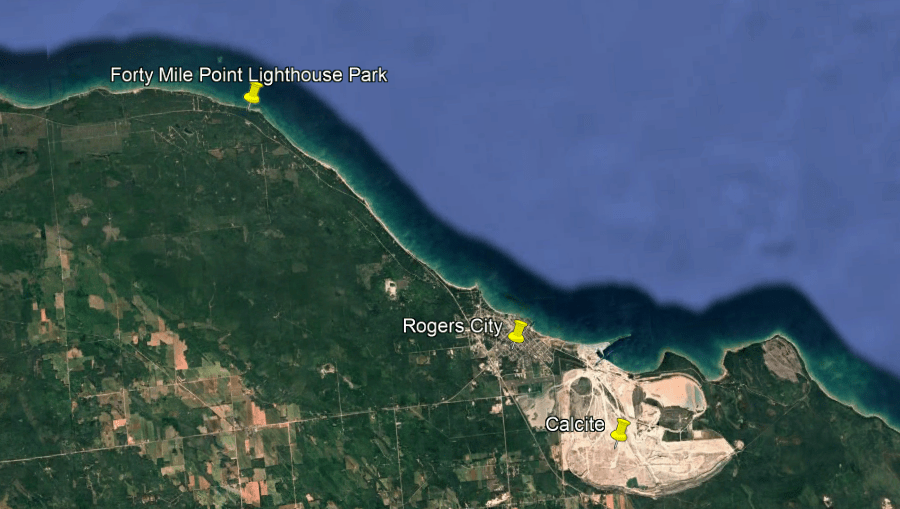

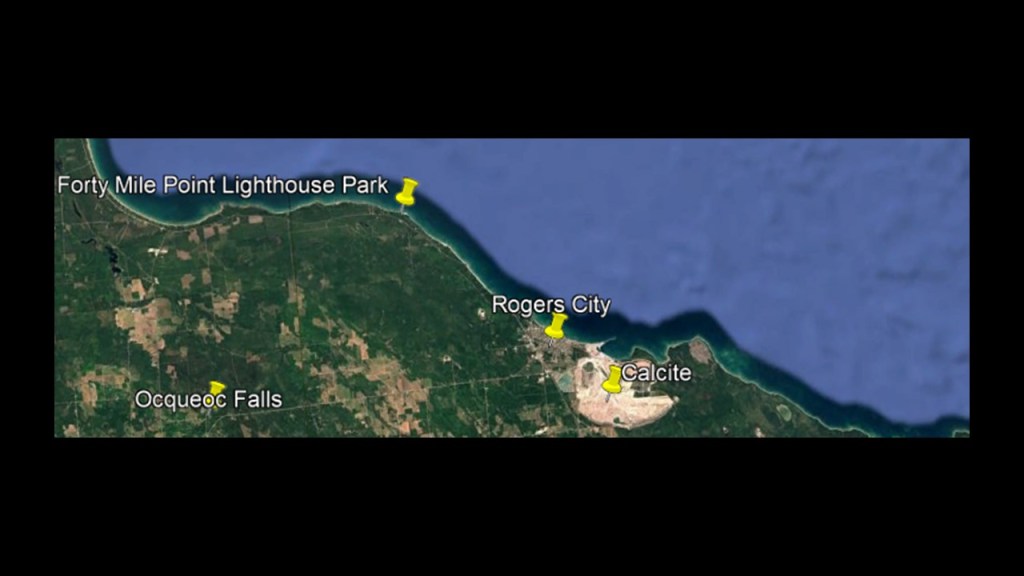

Rogers City is just a little ways down the coast from Cheboygan, where we find in the surrounding area the Forty Mile Point Lighthouse; Presque Isle and its Lighthouses; and the Ocqueoc Falls.

In our historical narrative, Rogers City was established in 1868 when William Rogers and several other people came to survey the area and for logging purposes in 1868, and that in 1870, post office was opened here.

It changed names and status several times over the years, but was eventually incorporated as a city in 1944.

Rogers City, the largest city in Presque Isle County, only had a population of 2,850 in the 2020 census.

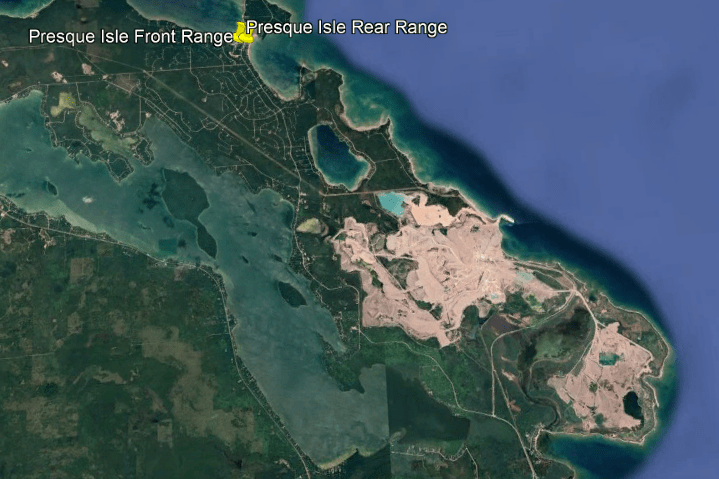

Yet, the world’s largest open-pit limestone Quarry happens to be within the Rogers City limits at the Port of Calcite, which is one of the largest shipping ports on the Great Lakes.

The Forty Mile Point Lighthouse Park is located just to the north of Rogers City.

This is what we are told about it.

It received its name from being a distance of 40-miles, or 64-kilometers, from the Old Mackinaw Point Lighthouse in Mackinaw City.

It was constructed with the intent that as one sailed from Mackinaw Point to the St. Clair River, one would never be without viewing range of a light house.

It’s construction was said to have been completed by 1896, and it was first lit in 1897.

The appearance of the Forty Mile Point Lighthouse on the top left brings the architectural style and building orientation I have seen in many places all over the Earth, including but not limited to, what is seen in Atchison, Kansas, on the top right; Santa Cruz de Tenerife on the bottom left; and the ancient city of Ouarzazate in Morocco, on the bottom right.

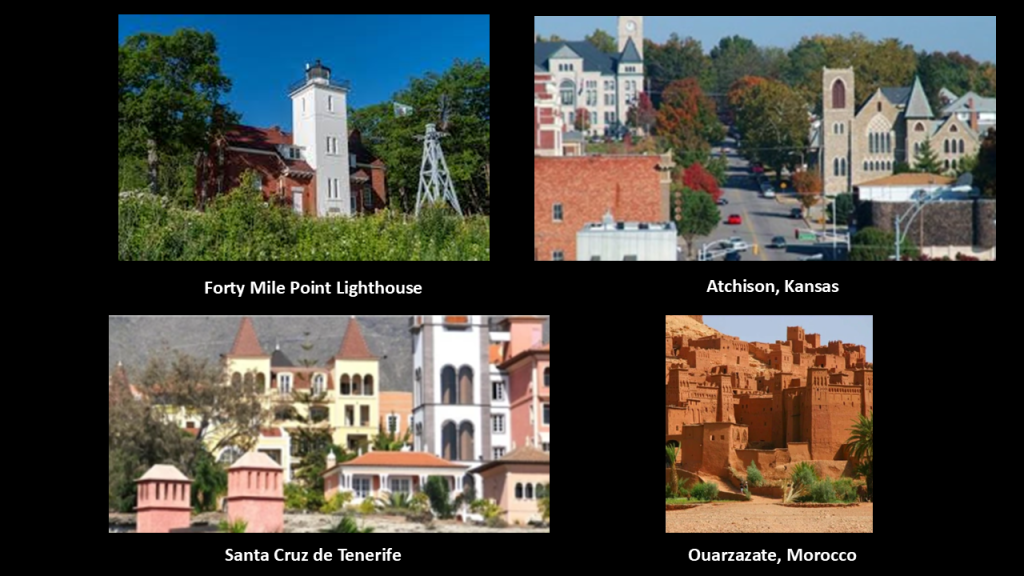

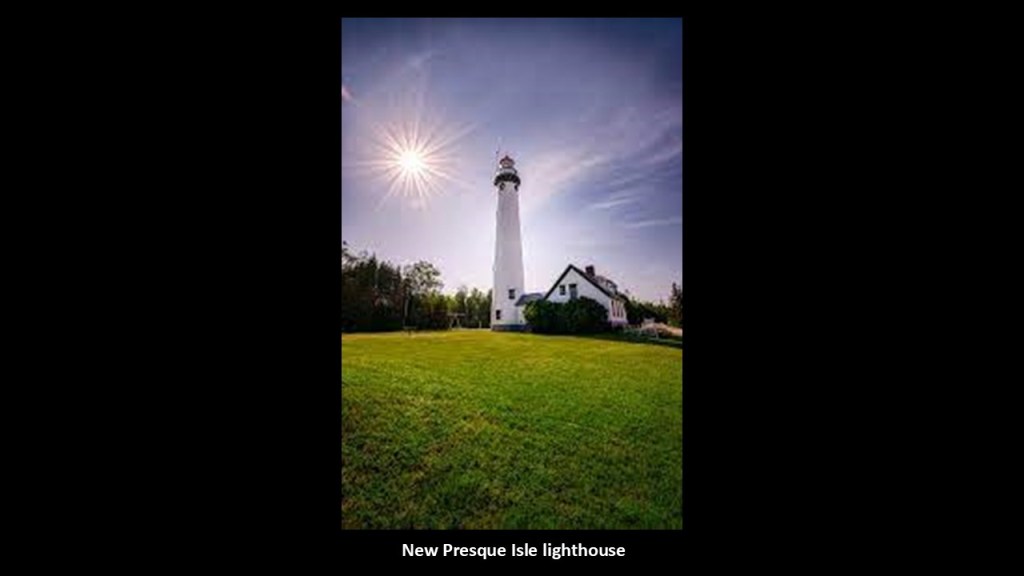

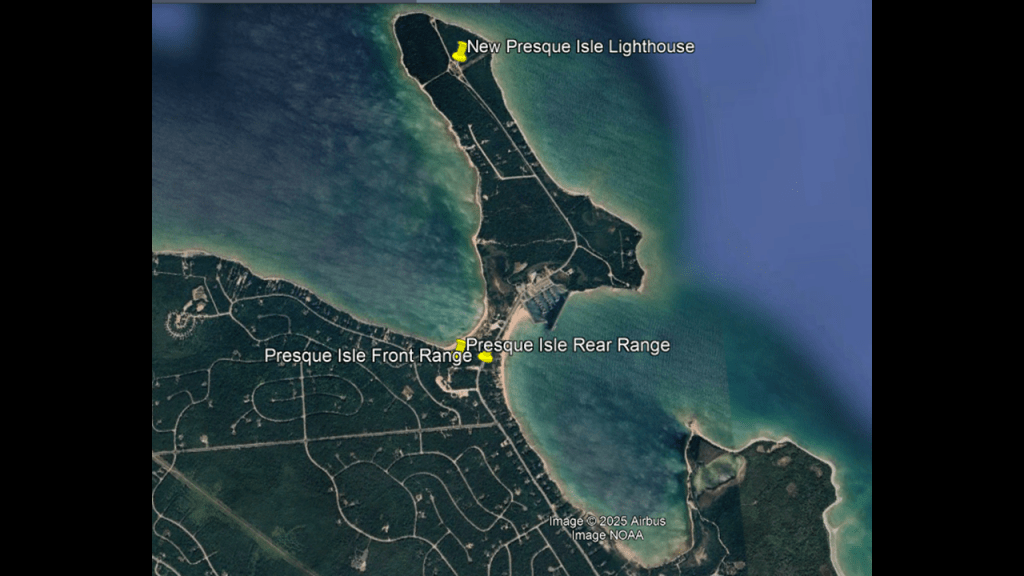

What we find in the area of the Presque Isle Harbor on the other side of Rogers City from the Forty Mile Point Lighthouse is the New Presque Isle lighthouse, the Front and Rear Range Lights, and the Presque Isle Quarry.

The New Presque Isle lighthouse was said to have been built in 1870, and is still an active aid to navigation.

It was said to have been built to replace the Old Presque Isle Lighthouse, which is not operational and a museum today.

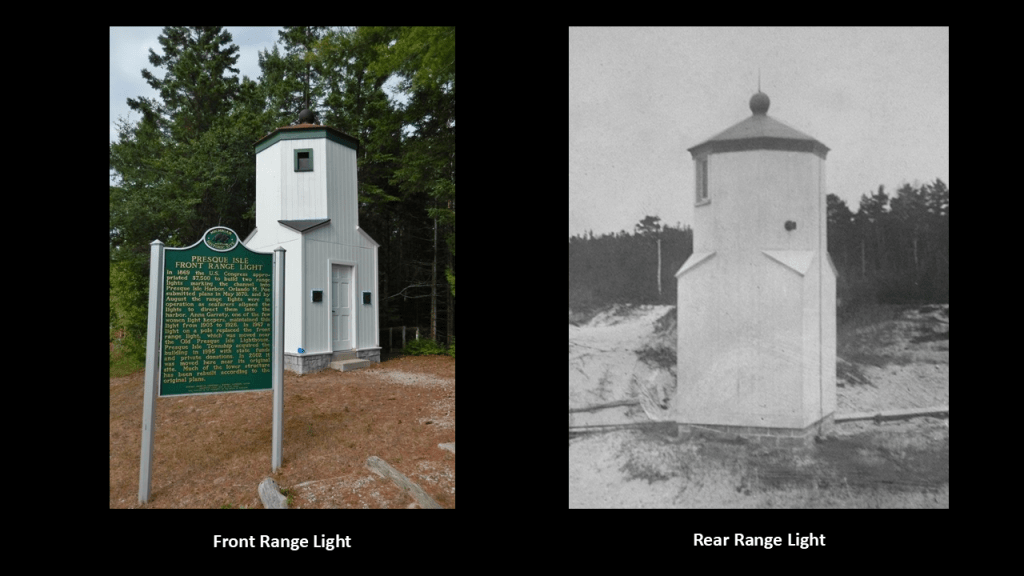

Like the New Presque Isle lighthouse, the Presque Isle Front and Rear Range Lights were also said to have been built in 1870.

They were said to have been built in the channel leading into the harbor to help mariners avoid the shallows on either side, and they are still active today.

They are right next to the Presque Island Quarry, one of the largest limestone quarries in the nation with two adjacent pits that extend for 5-miles, or 8-kilometers, along the shore of Lake Huron.

The Ocqueoc Falls are directly to the west of the Forty Mile Point Lighthouse; Rogers City; and Presque Isle.

The Ocqueoc Falls on the Ocqueoc River are one of the many waterfalls surrounding Lake Huron.

It is a popular recreational destination in the Lower Peninsula with hiking, biking, and camping opportunities.

It is the largest and only-named waterfall in the region, and the only universally-accessible one.

Similar to the previously-mentioned Tallulah Gorge and Falls in Georgia, at the falls, the Ocqueoc River drops 5-feet, or 1.5-meters, before entering a small gorge with rocky walls, and below the gorge flows into Lake Huron’s Hammond Bay.

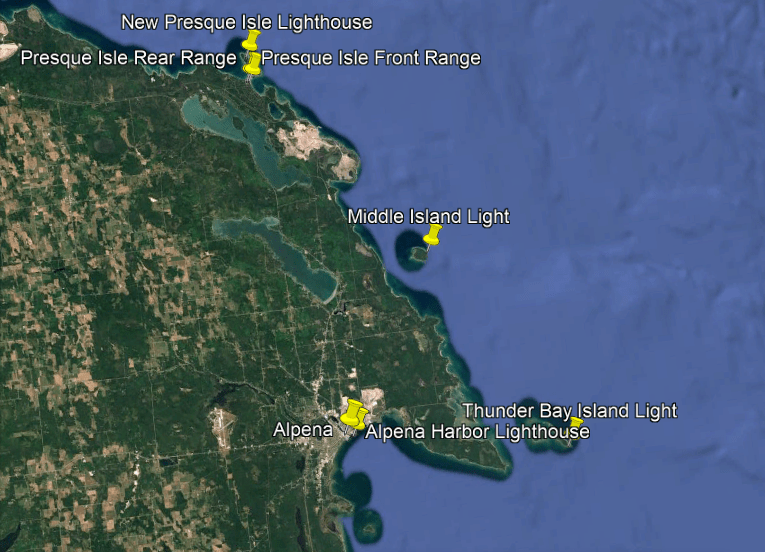

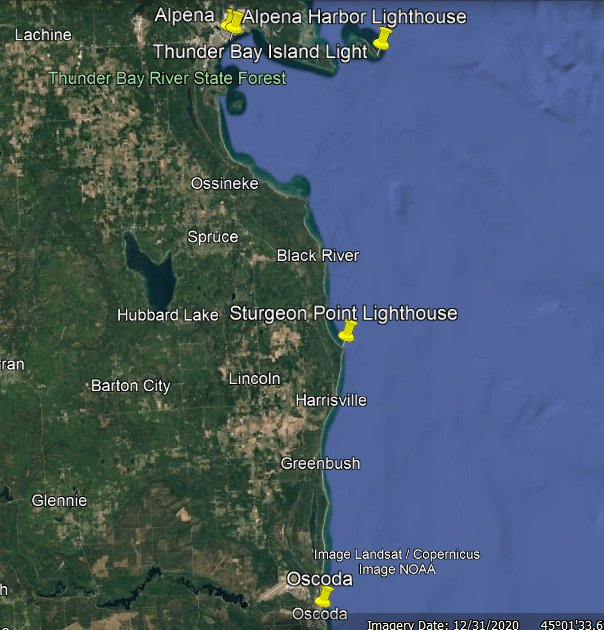

The next place we come to going down along the coast is Alpena.

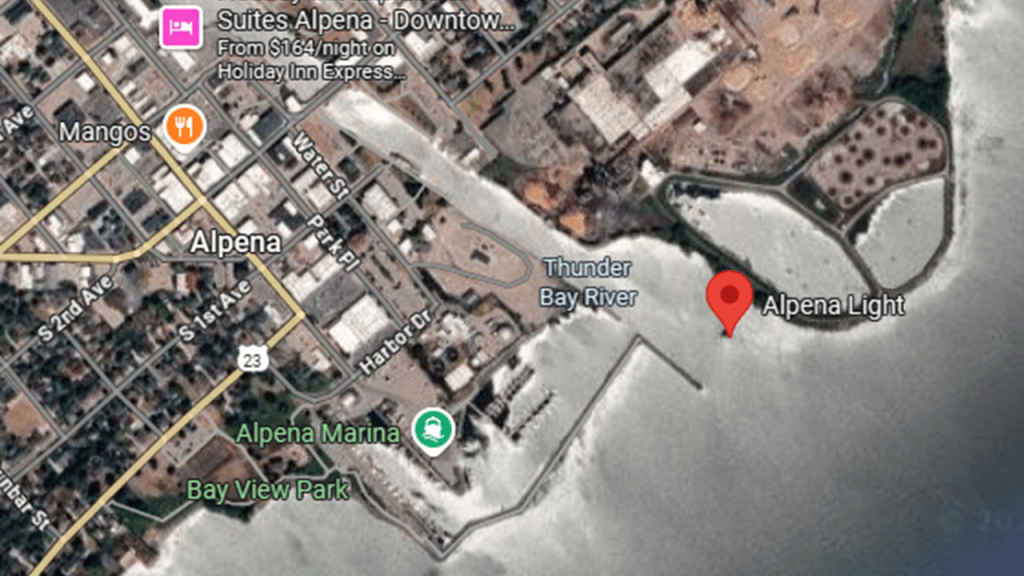

Besides being the location of Thunder Bay and the previously-mentioned Thunder Bay National Marine Sanctuary where approximately 100 shipwrecks are protected, there are three lighthouses here – Middle Island; Thunder Bay Island; and Alpena Harbor.

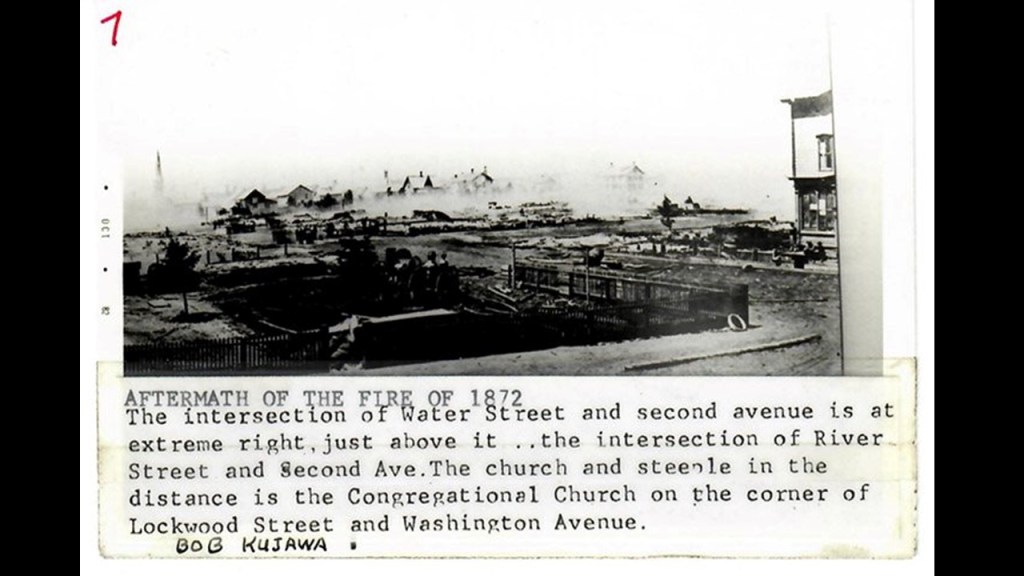

European settlement started in 1835, and Alpena was officially incorporated by the Michigan State Legislature on March 29th of 1871, which is interesting because on October 8th of 1871, we are told most of the city was lost in the Manistee Fire, one of three fires in Michigan on that same day known collectively as the Great Michigan Fire, which also took place on the same day as the Great Chicago Fire and the Peshtigo Fire in Wisconsin on Lake Michigan.

Then there was another fire less than a year later, on July 12th of 1872, which destroyed an additional 65-or-so homes and businesses, and then we are told yet another disastrous fire for Alpena happened again in 1888.

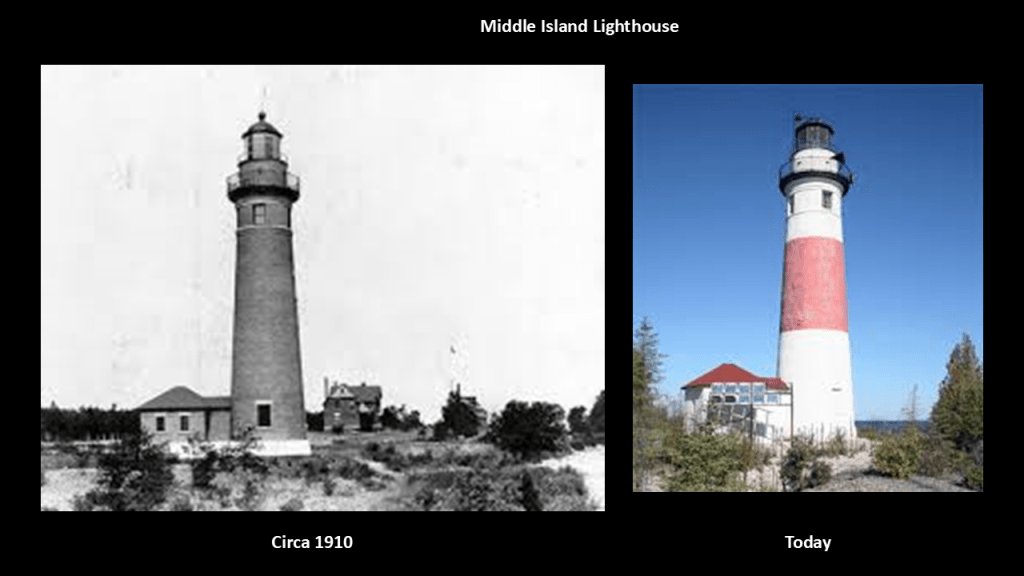

The Middle Island Lighthouse is 10-miles, or 16-kilometers, north of Alpena, Michigan.

We are told that it was a midway point between Presque Isle Harbor to the north and Thunder Bay to the south, and that one side of the island offered safe harbor, and the other side guarded by shoals and considered a particularly dangerous spot for ships.

We are told the construction of the brick lighthouse there today started in June of 1904 and was completed and operational by June of 1905.

The Thunder Bay Island Lighthouse is said to be one of the oldest operating lighthouses in Michigan.

Our historical narrative tells us the one standing today was said to have been built in 1857, with two others having been built there, one in 1831 that disintegrated almost immediately, and another in 1832 out of local limestone.

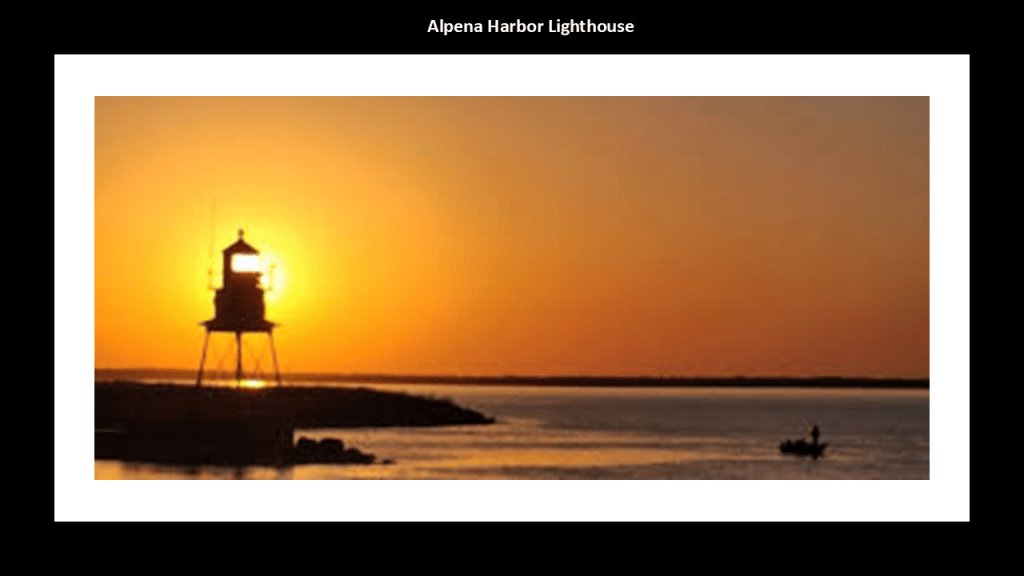

The Alpena Harbor Lighthouse stands on the north breakwater of the Alpena, which marks the entrance to the Thunder Bay River from the Thunder Bay.

The current lighthouse was said to have been there since 1914, replacing earlier wooden structures in use between 1877 and 1888.

The history of the city of Alpena is closely connected with the lumber industry.

Founded during the 19th-century lumber boom, it became a major lumber harvesting and processing center.

Leaving the Alpena area and heading down the coast we come next to the Sturgeon Point Lighthouse and unincorporated community of Oscoda.

The Sturgeon Point Lighthouse in today’s Sturgeon Point State Park was said to have been built in the “Cape Cod Style Great Lakes Lighthouse” in 1869 in order to ward ships off a reef that extends 1.5-miles, or 2.4-kilometers, lakeward from Sturgeon Point which was responsible for a large number of lost ships and men.

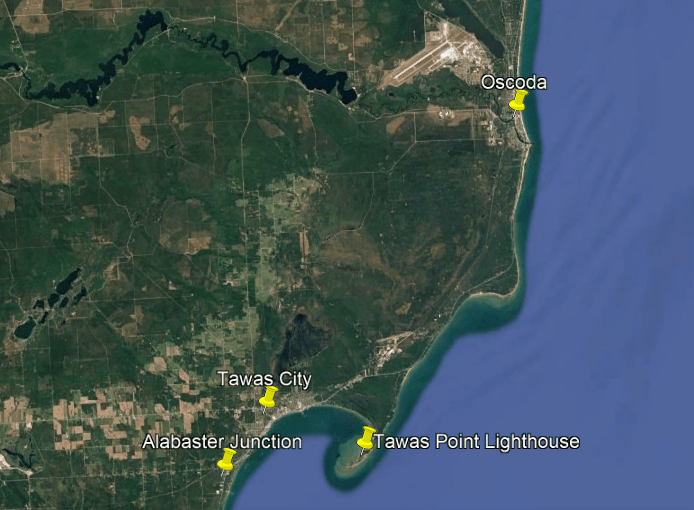

Oscoda is located at the mouth of the Au Sable River where it enters Lake Huron.

We are told the area was first settled in 1867 when a law firm purchased land and platted a community, with the Oscoda Post Office established on July 1st of 1875.

There’s a Lumberman’s Monument in the area that was dedicated in 1932 to the lumbermen that first settled here.

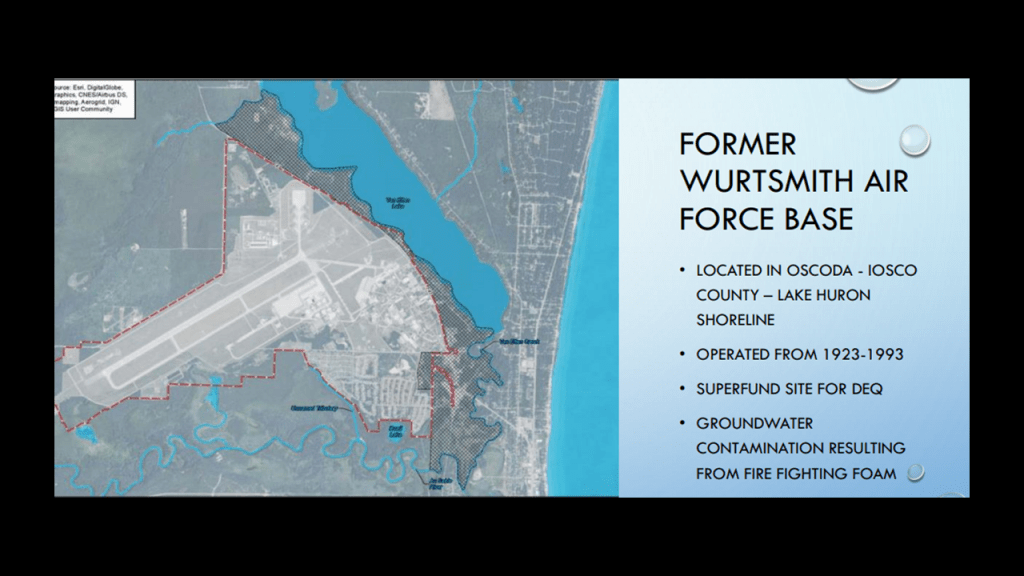

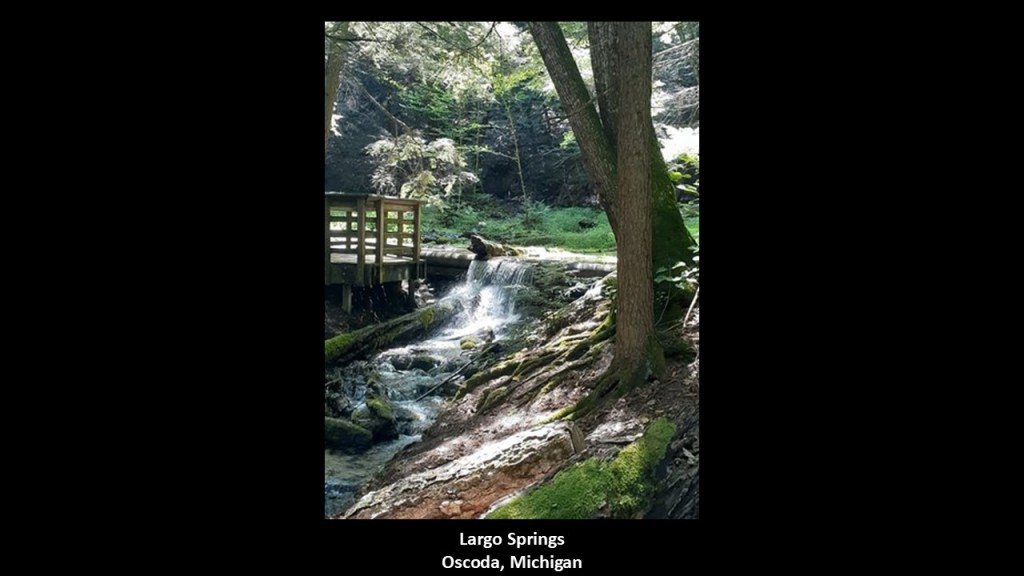

Noteworthy places include the former Wurtsmith Air Force Base, Largo Springs, and the Tuttle Marsh Wildlife Area.

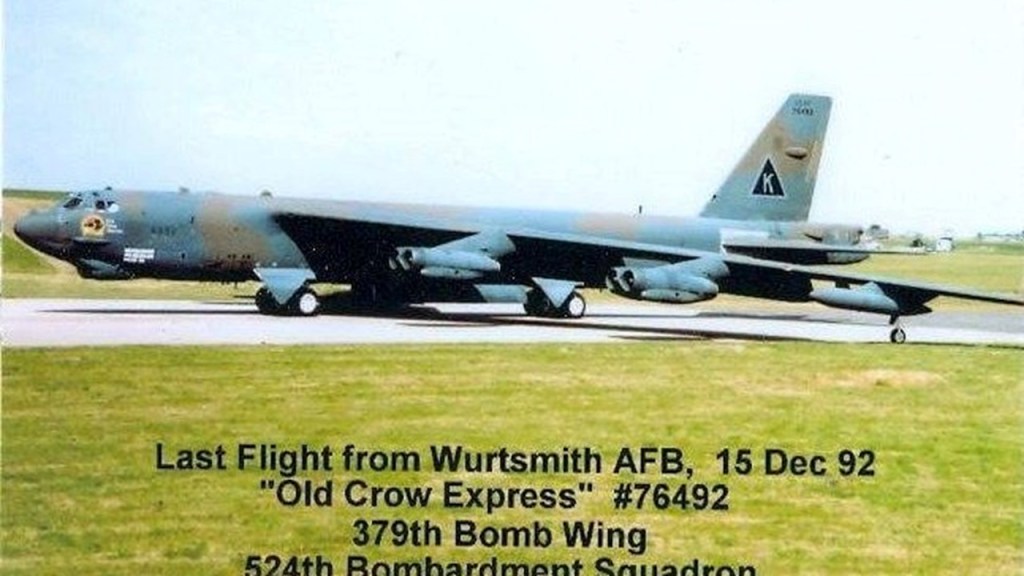

Wurtsmith Air Force Base was commissioned here in 1923, and was one of three Strategic Air Command bases that housed B-52 bombers.

The base was decommissioned in 1993, and the area is now an on-going Superfund site due to extensive groundwater contamination.

A part of the former airbase is still used as a public-use airport.

Largo Springs in Oscoda has several viewing docks and a boardwalk through natural springs.

Largo Springs was a CCC site in 1934, like other places we have seen so far in this series.

There is no doubt in my mind that the CCC, and the other alphabet programs of FDR’s New Deal during the Great Depression, like the WPA and TVA, were being used to cover-up the ancient advanced civilization.

The entrance to the Tuttle Marsh Wildlife Area is approximately 5-miles, or 8-kilometers, west of Oscoda on Old US Highway 23, the same US-23 I mentioned earlier in this post that goes from Jacksonville in Florida to Mackinaw City in Michigan, and has connections both to the Tallulah Falls and Gorge in Georgia, and the Tahquemenon Falls in the Upper Peninsula of Michigan by way of Michigan State Highway 123, and are accessible from Michigan Highway 28, and both these places have historic railroad connections.

As I have been saying in this series and in other work I have done, I consistently find the presence of swamps, marshes, deserts and dunes along the leylines I have been tracking over a long-distances for a long time, from place-to-place-to-place.

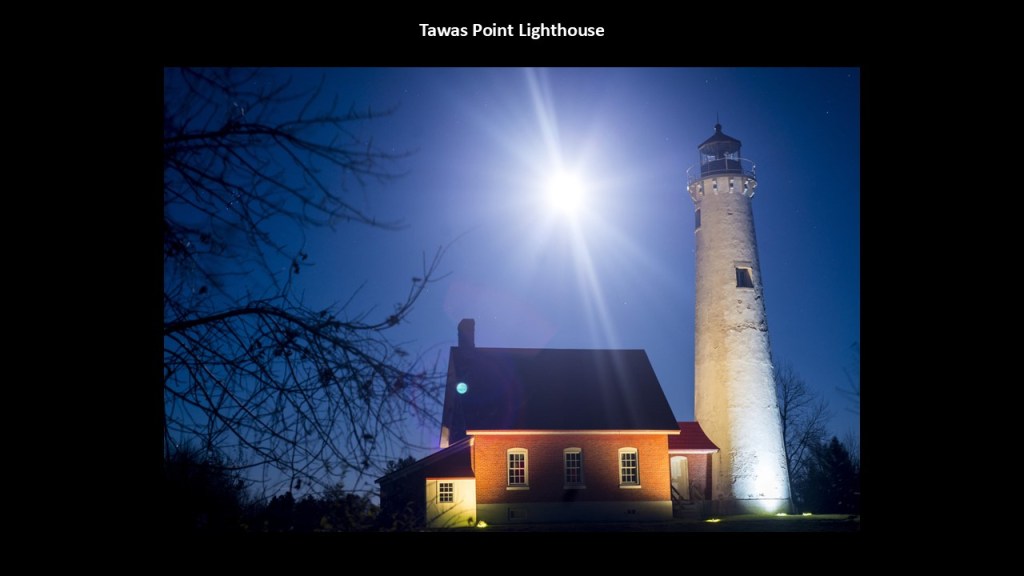

The next places I would like to bring your attention to down the coast is what is found in the vicinity of the Tawas Point Lighthouse, which also includes Tawas City and Alabaster Junction.

The Tawas Point Lighthouse is contained within the Tawas Point State Park, a public recreation area.

This is the second lighthouse said to have been built at this location between 1876 and 1877, with the first one said to have been constructed between 1852 and 1853, with Tawas point itself being a serious hazard to navigation with shifting sands.

We are told it was originally named “Ottawa Point,” and the name changed to “Tawas Point” in 1902.

Here is the Tawas Point Lighthouse with a full moon known as a “Supermoon” rising directly behind it back in November of 2016.

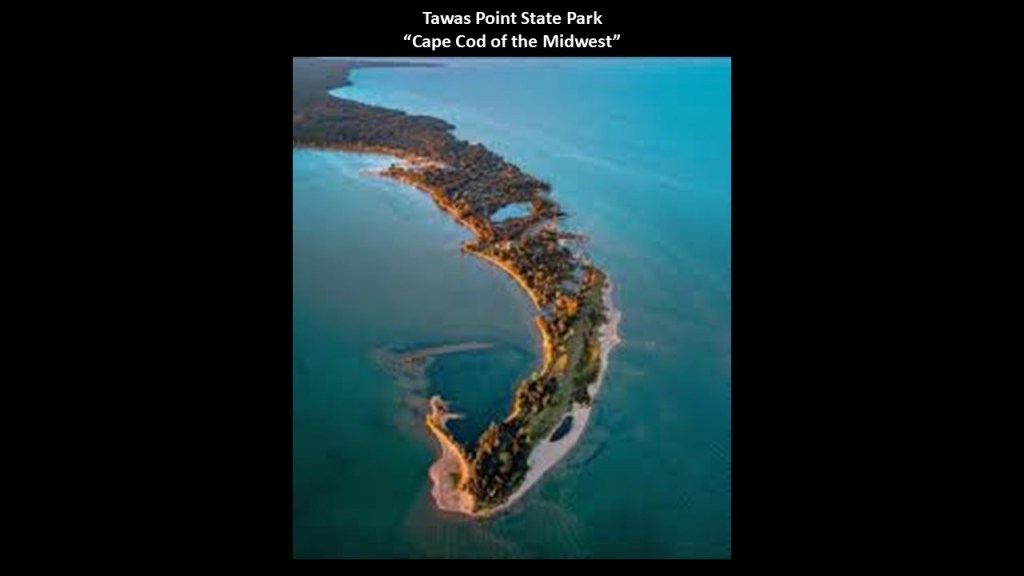

The Tawas Point State Park is located on 183-acres, or 74-hectares, at the end of a sand-spit that forms Tawas Bay.

This location in Michigan has been referred to as the “Cape Cod of the Midwest.”

This is an interesting reference to make because not only does Tawas Point have the same curving appearance as Cape Cod, the location of Cape Cod in Massachusetts has the same features that we have seen in the Great Lakes, like extreme weather, shipwrecks, and shallow bathymetry…

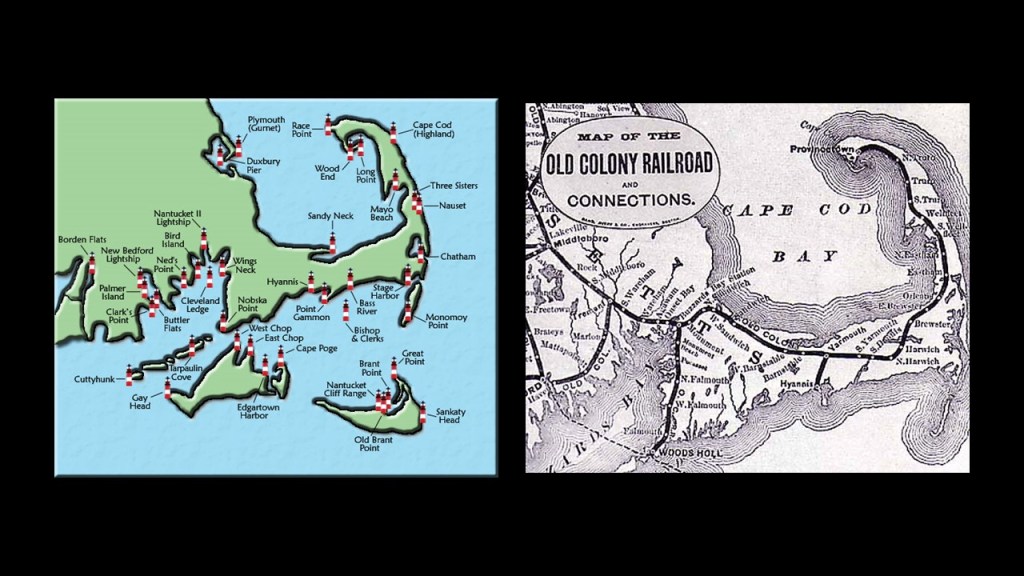

…as well as lighthouses and historic railroad beside the coastal areas.

Here is the map showing fourteen lighthouses on Cape Cod alone, as well as other lighthouses of this part of New England, on the left, as well as the historic Old Colony Railroad that traversed the length of the narrow Cape Cod.

Again, it is my working premise the lighthouses and railroad, and star forts for that matter, were once working components of the Earth’s original energy grid, and that land masses sank around them when the energy grid was deliberately targeted for destruction by the Dark Forces directly responsible for the world we live in today, and the destruction of the energy grid is what brought us the bodies of water we see today that weren’t there prior to this event.

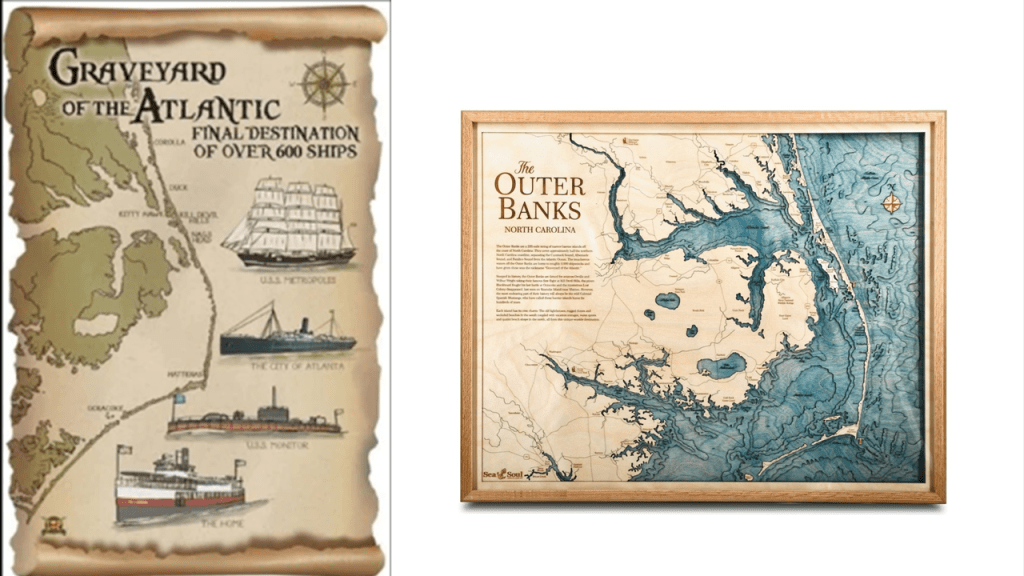

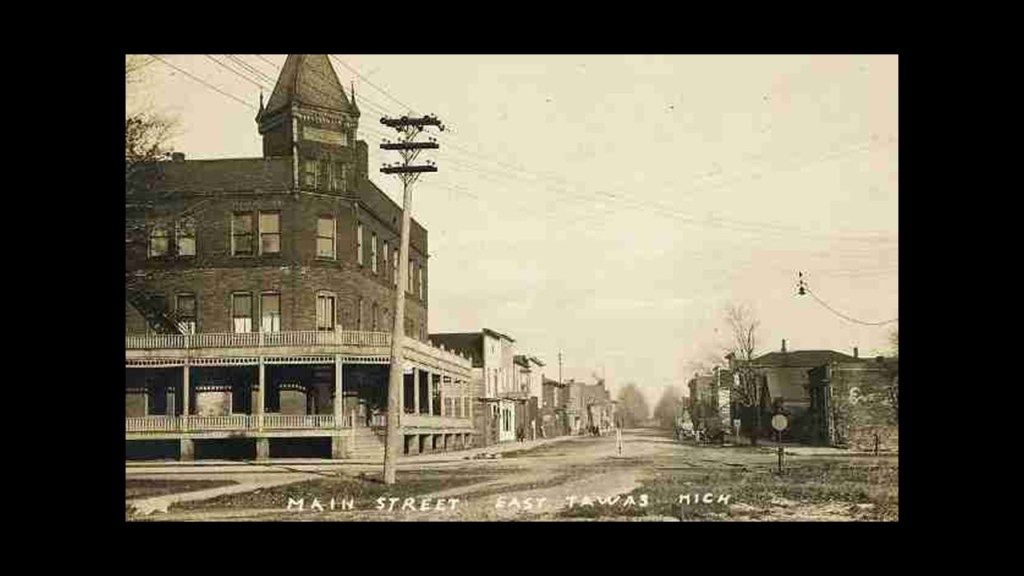

Like the Great Lakes and Cape Cod in Massachusetts, the treacherous waters of the Outer Banks in North Carolina have also given it the nickname of “Graveyard of the Atlantic” because of the numerous shipwrecks that have occurred here because of its treacherous waters consisting of things like shallows, shifting sands, and strong currents.

We are told the nearby Tawas City was founded in 1854, and was the first city located on the shores of Saginaw Bay and Lake Huron north of Bay City.

The forest lands of the area supported a lumber and sawmill industry early in its history like so many of the other places we have seen along the way.

It is interesting to note that this photo was notated as the Main Street of East Tawas City in 1910.

Tawas City is on US-23.

US-23 has been designated the “Sunrise Side Coastal Highway” as it runs along the Lake Huron Shoreline.

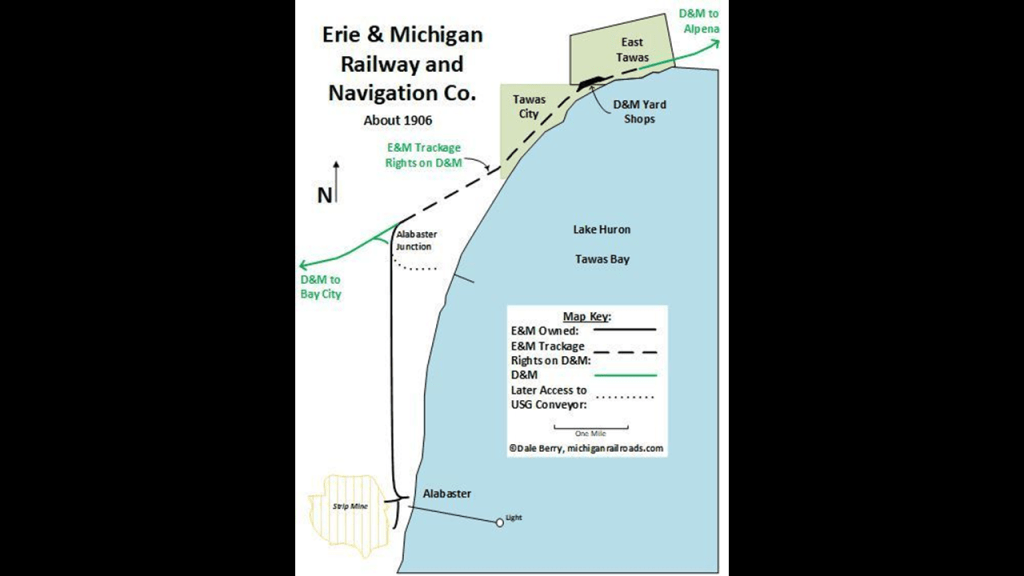

Alabaster Junction is a short-distance south of Tawas City on US-23.

It was formerly a location on the Detroit, Bay City & Alpena Railroad, later known as the D & M, Lake States Railroad.

A branch known as the Erie & Michigan Railway & Navigation company left the mainline here, and served the Alabaster gypsum quarry along the Lake Huron shoreline.

It held the world’s record for equipment per mile of track, from Alabaster on the shore of Tawas Bay to East Tawas, which is a distance of 11-miles, or 18-kilometers.

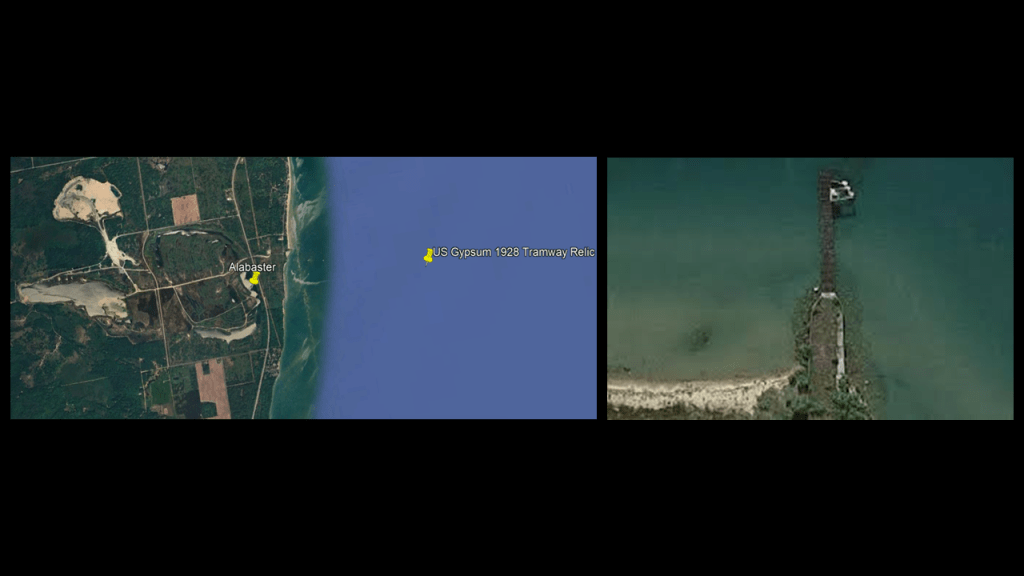

These days, Alabaster is an abandoned mining complex that consists of an open-pit gypsum mine, and the remains of processing buildings, shops, and offices, an abandoned railroad and what we are told was an elevated marine tramway that that spanned 1.5-miles, or 2.4-kilometers, into Saginaw Bay.

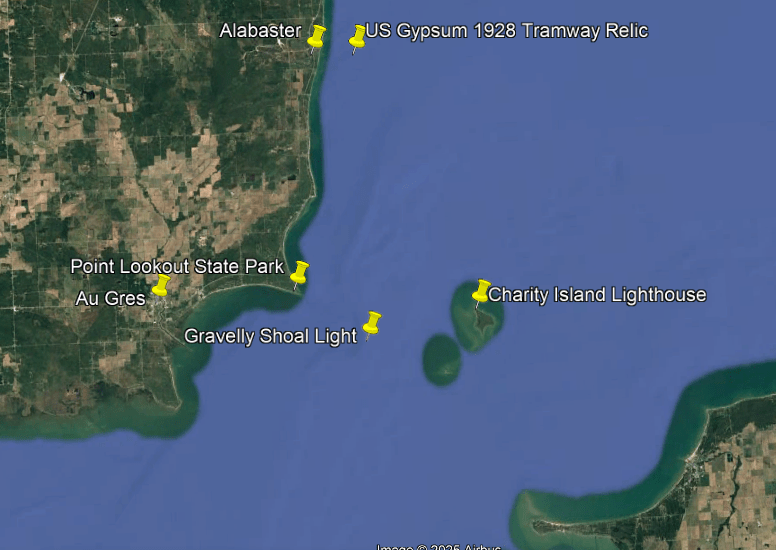

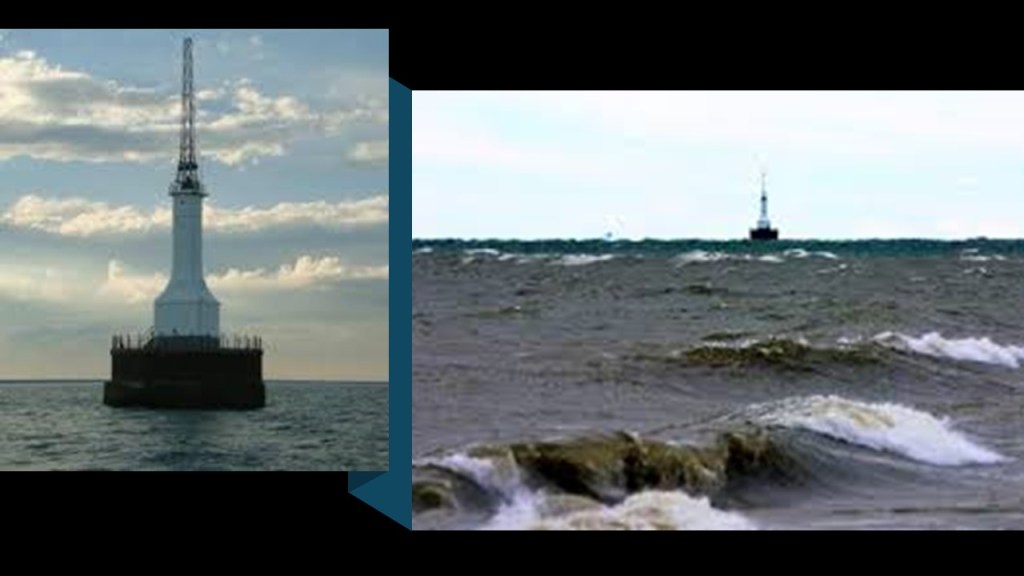

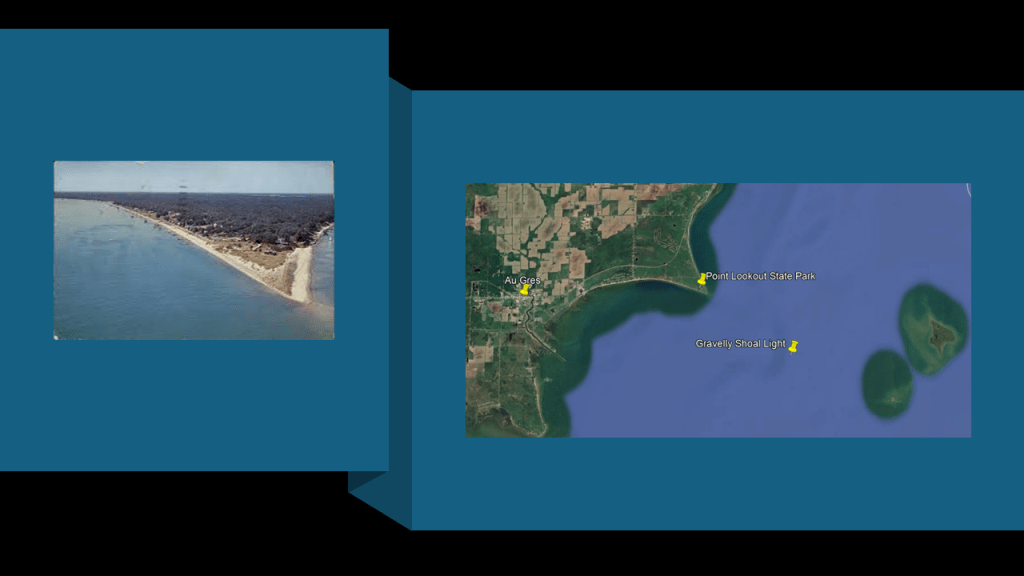

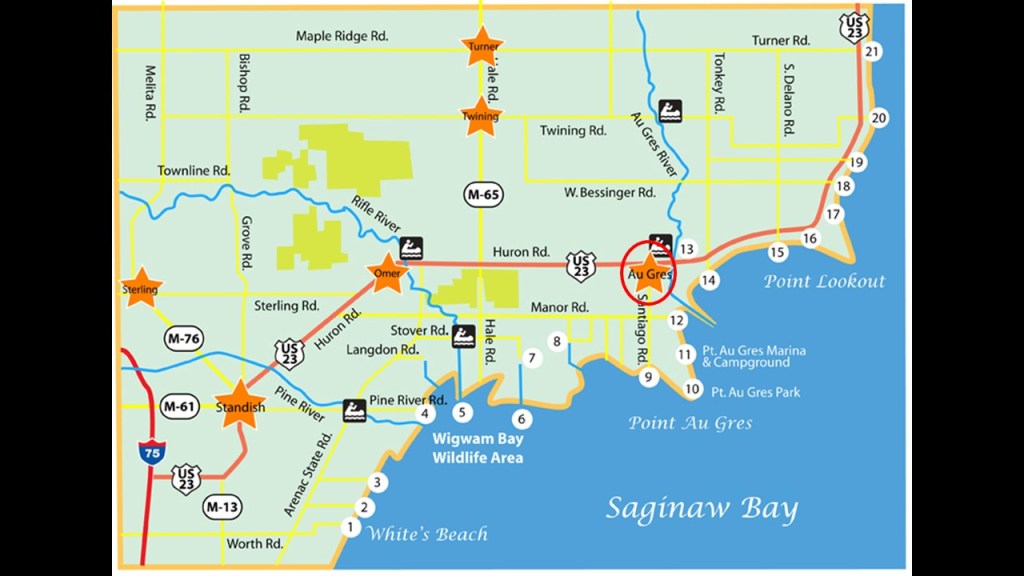

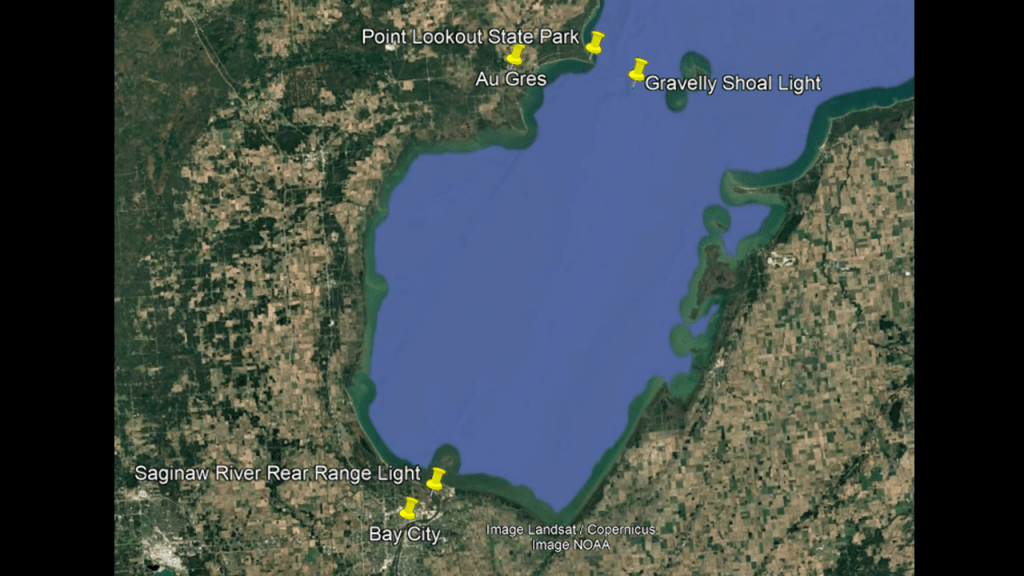

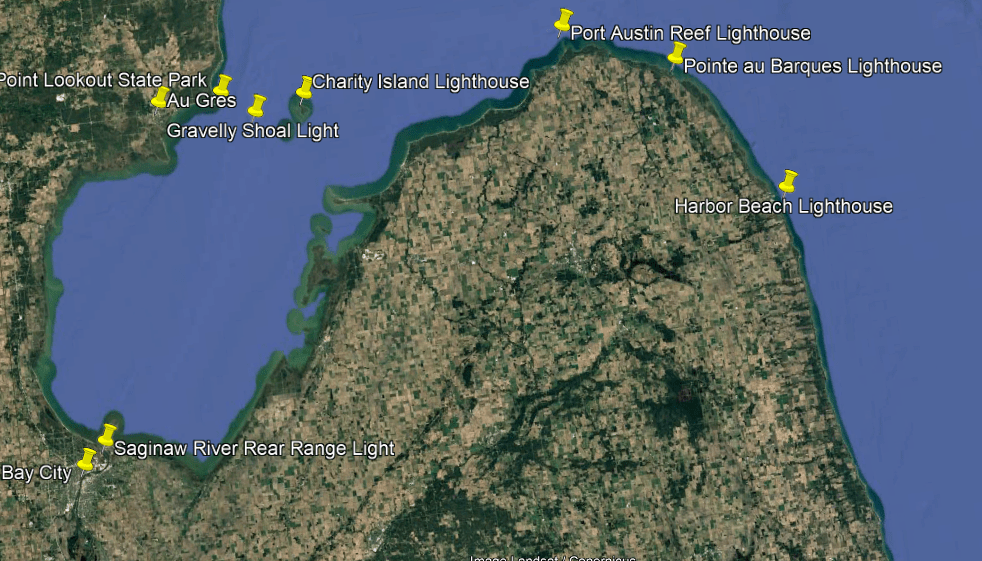

The next community we come to with a lighthouse nearby is Au Gres, and the Gravelly Shoal and Charity Island Lighthouses southeast of Point Lookout on the western-side of Saginaw Bay.

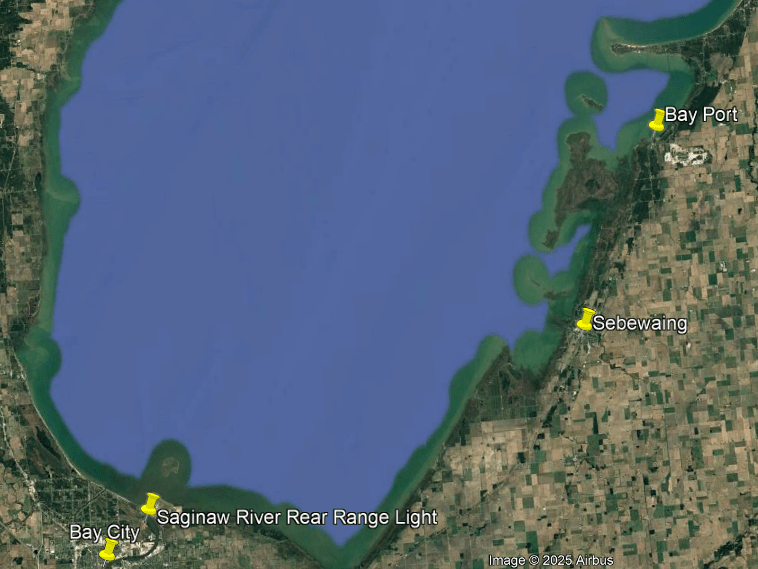

Like we saw towards the beginning of this post, the Saginaw Bay is quite shallow, ranging in depth from 0 – 100-meters or 328-feet.

The Gravelly Shoal Lighthouse is an active aid to navigation on the shallow shoals extending to the southeast from Point Lookout.

It was said to have been constructed in 1939 as part of FDRs New Deal and its program to “Put America Back to Work.”

The Charity Island Lighthouse was said to have been constructed in 1857 and abandoned in 1939 when the Gravelly Shoal Lighthouse became operational.

Today the former Lighthouse Keepers quarters have been renovated and it is an active VRBO accommodation.

Point Lookout State Park is approximately half-way between Tawas City and the mouth of the Saginaw River in Bay City.

The nearby Au Gres was first settled in 1862 by construction workers on the Saginaw – Au Sable State Road, and Au Gres incorporated as a city in 1905.

Its population was 945 in the 2020 census.

It is also located on US-23.

Next I am going to head on down to Bay City area at the mouth of the Saginaw River where it enters Saginaw Bay.

Saginaw Bay forms the space between Michigan’s Thumb Region and the rest of the Lower Peninsula.

Bay City is the principal city of the Bay City metropolitan area, and the county seat of Bay County.

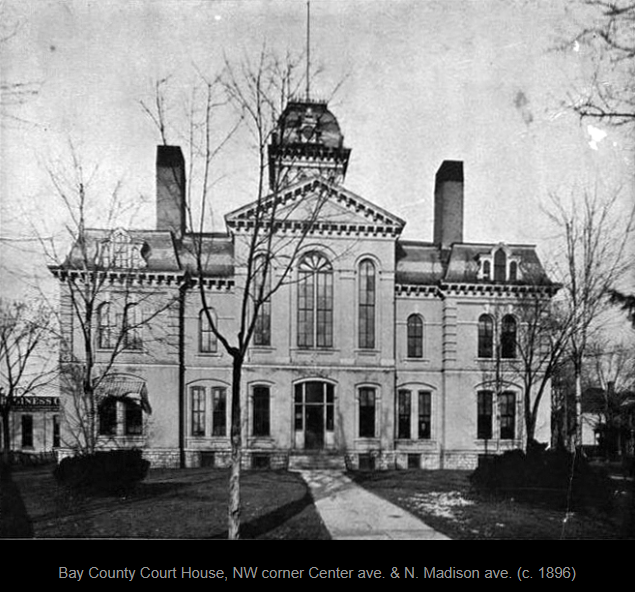

Here are some photos I found of historical buildings in Bay City, like the Bay County Courthouse circa 1896…

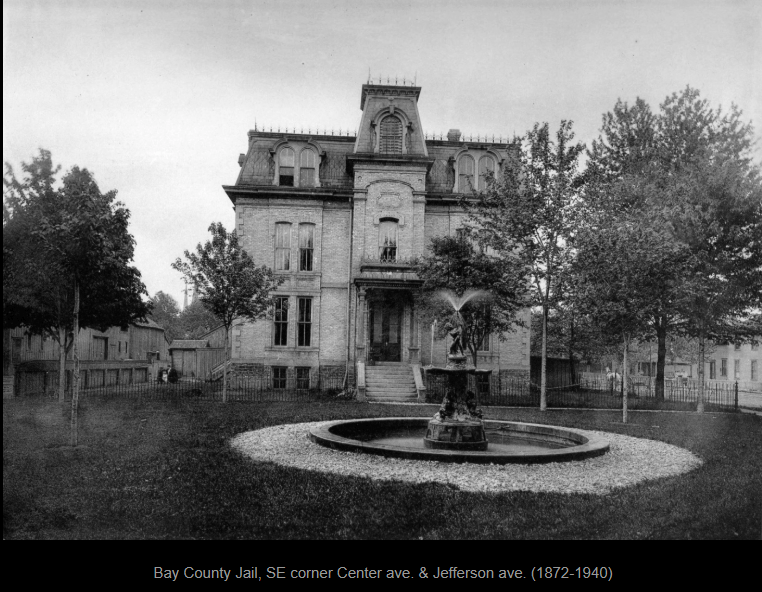

…the Bay County Jail that we are told existed from 1870 to 1940…

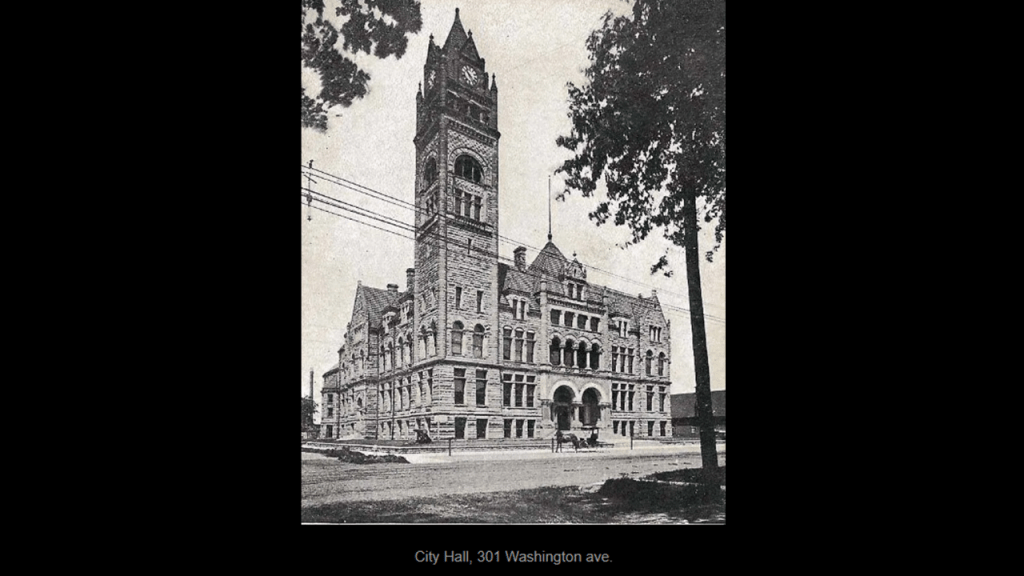

…the historic Bay City Hall…

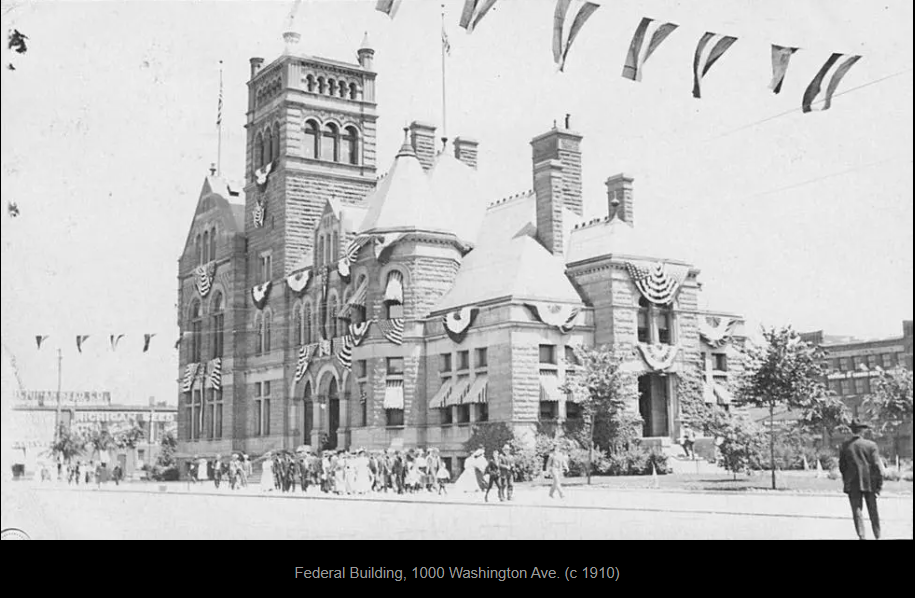

…and the Federal Building in Bay City circa 1910.

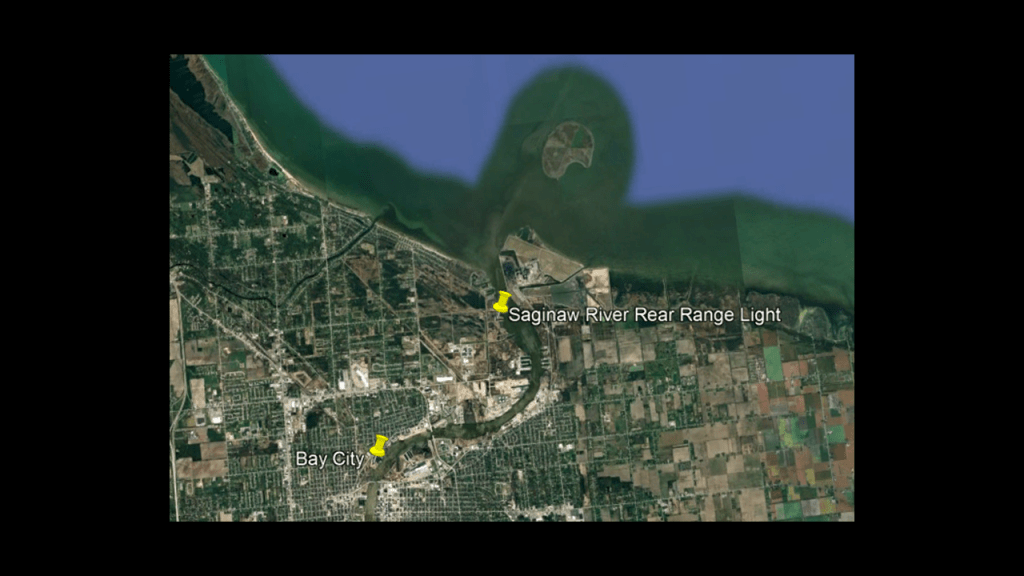

The Saginaw River Rear Range Light is in Bay City at the entrance of the Saginaw River into Saginaw Bay.

We are told in our historical narrative that the U. S. Army Corps of Engineers dredged the Saginaw River to allow larger ships to travel upriver, and that this change required the placement of lighthouses, and that in 1876 a pair of range lights had been erected.

The first lighthouse, the “front range light,” was completely removed by the 1960s.

The Saginaw River Rear Range Light is still there but deactivated in 1960.

Interestingly, the Dow Chemical Company, which already owned the land surrounding the Rear Range Light, purchased the lighthouse in 1986, and then proceeded to board it up until 1999, when the Saginaw River Marine Historical Society approached Dow about renovating it and opening to the public, though all these years later it is not permanently open to the public, seemingly just for special occasions like the Tall Ship Celebration in Bay City in 2019, which was the last time it was open to the public.

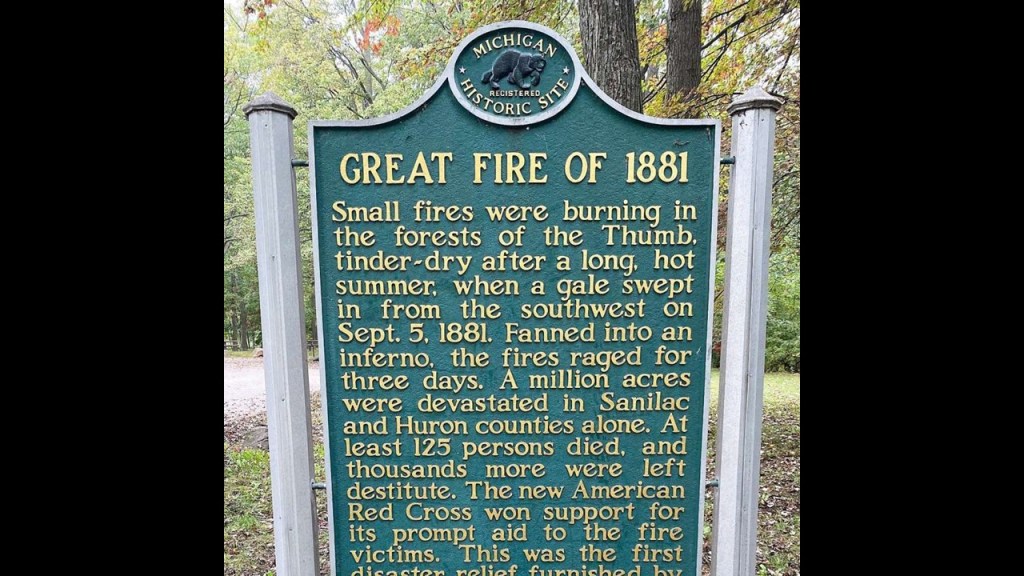

Now we are offically heading into the region known as “The Thumb,” travelling along what is known as “The Thumb Coast.”

It is noteworthy that the Huron Fire took place on October 8th of 1871, which burned a total of 1.2-million-acres, of Michigan’s Thumb region.

This was the exact same day as the Great Chicago Fire and the Peshtigo Fire in Wisconsin, as well as two other fires in Michigan – in Manistee and Holland.

Then, almost ten-years later to the day, on on September 5th of 1881, the Michigan Thumb Fire started, with hurricane-force winds and hot and dry conditions.

Interesting to note the following descriptions that accompanied the 1881 Michigan Thumb Fire.

Soot and ash from the fire caused sunlight to be obscured in places on the U. S. East Coast and in New England, the sky had a yellow appearance, and which caused a strange luminosity in and on buildings and vegetation, and Tuesday, September 6th of 1881, became known as “Yellow Tuesday” because of this unsettling event.

The first official disaster relief operation of the American Red Cross was responding to the Thumb Fire less than four months after the establishment of the American Red Cross.

The American Red Cross was founded in 1881 by Clara Barton as a non-profit humanitarian organization that provides emergency assistance, as well as disaster relief and disaster preparedness education.

Clara Barton had been a hospital nurse during the American Civil War.

She had connections in upstate New York, and the American Red Cross was established on May 21st of 1881 in Dansville, New York, and the first local chapter was at the English Evangelical Lutheran Church of Dansville.

Other names involved in the establishment of the American Red Cross included Senator Omar D. Conger, who had a home in Dansville where its founders met…

….even though he was one of the Senator’s for Michigan and had lived and worked in Port Huron, in Michigan’s region known as “The Thumb.”

An early example of Problem – Reaction – Solution?

Did they actually create the disasters, and then provide the response to the disasters?

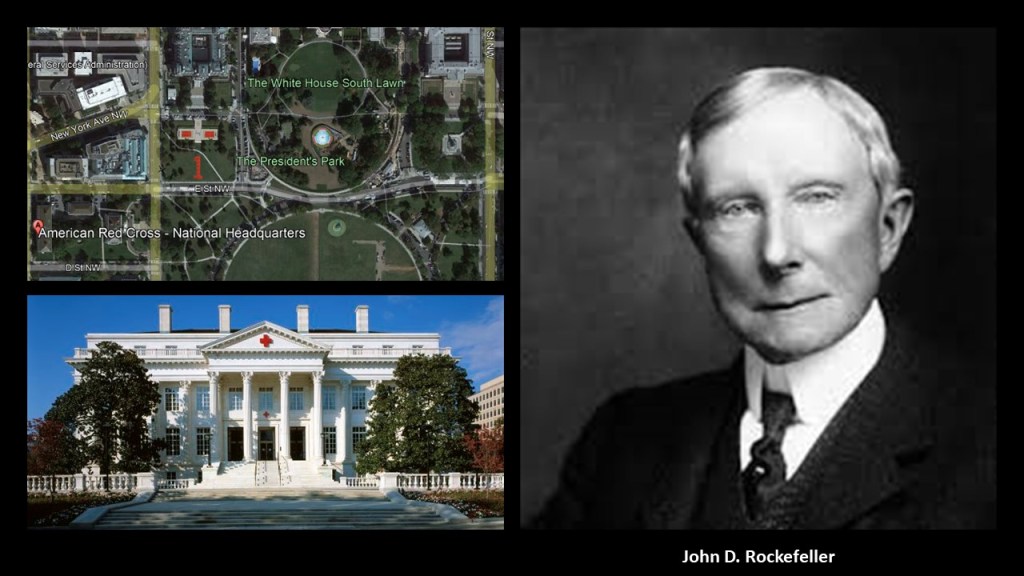

John D. Rockefeller was amongst several that donated to create a national headquarters near the White House in Washington, DC, said to have been built between 1915 and 1917.

So as we make our way up the Thumb Coast from Bay City, we come to places like Sebewaing and Bay Port, along what appears to be a continuing ruined shore-line.

I have documented similar findings along shore-lines in multiple places, including, but not limited to, when I was doing the research for “Recovering Lost History from the Estuaries, Pine Barrens & Elite Enclaves off the Atlantic Northeast Coast of the United States,” in January of 2023.

My research findings of many included the ruined-looking appearance of the shoreline from the South Jersey Shore on up through the Southshore of Long Island.

Here’s a closer a look at the South Jersey shoreline up to the New York-New Jersey Estuary System, so you can get a better view of what I am referring to on the left, and then what the shoreline looks like going from the New York – New Jersey Estuary System across Long Island to Montauk Point on the right.

And in spite of the marshy and wetland quality of the landscape hereabouts, this whole area is prime and valuable real estate that is, among other things, coveted by the very wealthy in our society.

This part of the world is highly prized by those of wealth and prestige.

So Sebewaing in Michigan for example, is notable for being the “Sugar Beet Capital,” in a region and state known for being major sugar beet producers.

The next place we come to up the Thumb Coast that I would like to mention is Bay Port.

While today Bay Port had a population of a little under 600 people in the 2020 Census, in 1886. the railroad came through here, and commercial fishing became a viable economic industry in the area.

The Bay Port Fish Company was established by investors in 1895, and Lake Herring, Walleye, and Whitefish were shipped via ice-filled rail cars to customers throughout the eastern United States.

Bay Port was considered the largest freshwater fishing port in the world by the 1920s and 1930s.

Then in 1945, a fire destroyed much of the Fish Company’s buildings and eventually over a period of decades, the large-scale commercial fishing industry went away.

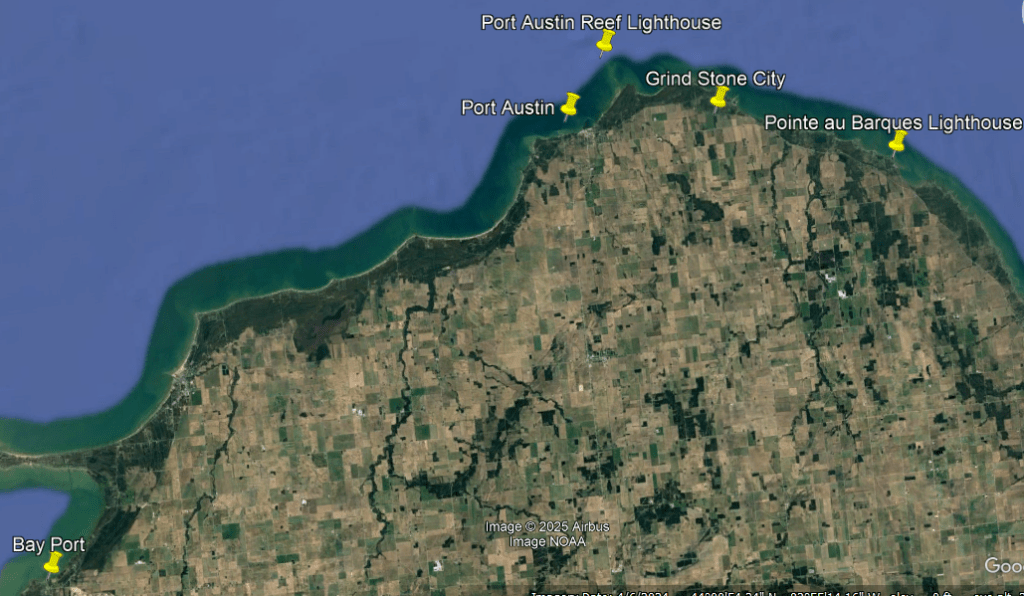

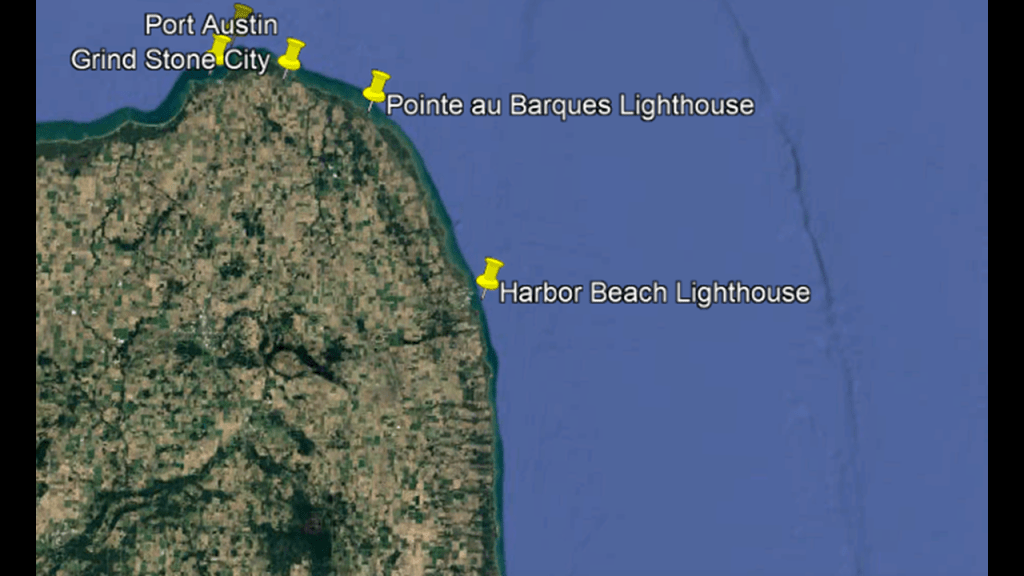

Further up the Thumb Coast at the top of the mitten we come to Port Austin; the Port Austin Reef Lighthouse; Grind Stone City; and the Pointe au Barques Lighthouse.

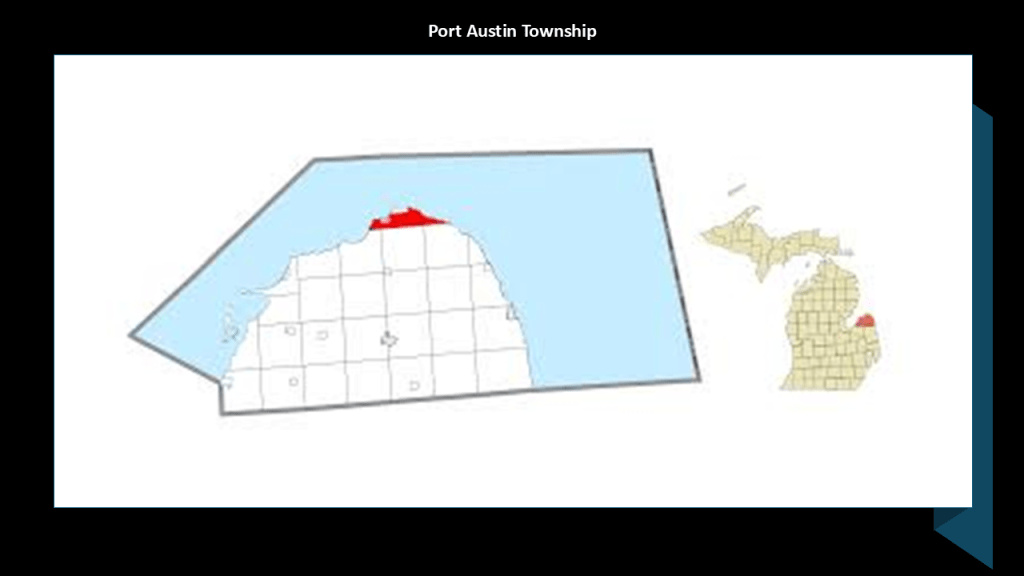

Port Austin was a village of 664 people in the 2010 census.

It is on the western end of the larger Port Austin Township in Huron County, with a population of 1,384 in the 2020 census.

Port Austin is the northern terminus of Michigan Highway 53, of which Detroit is the southern terminus.

Port Austin is the location of “Turnip Rock,” described as a geological formation classified as a stack in shallow water a very short distance offshore, we will continue to see these as we make our way around the shores of Lake Huron.

I think “formations” like these are remnants of sunken infrastructure and land.

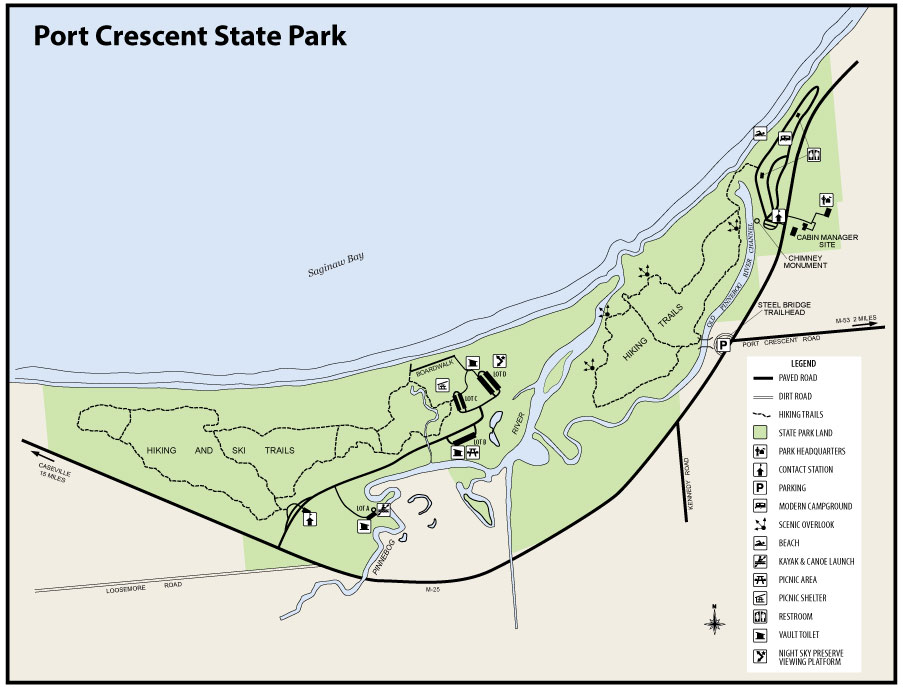

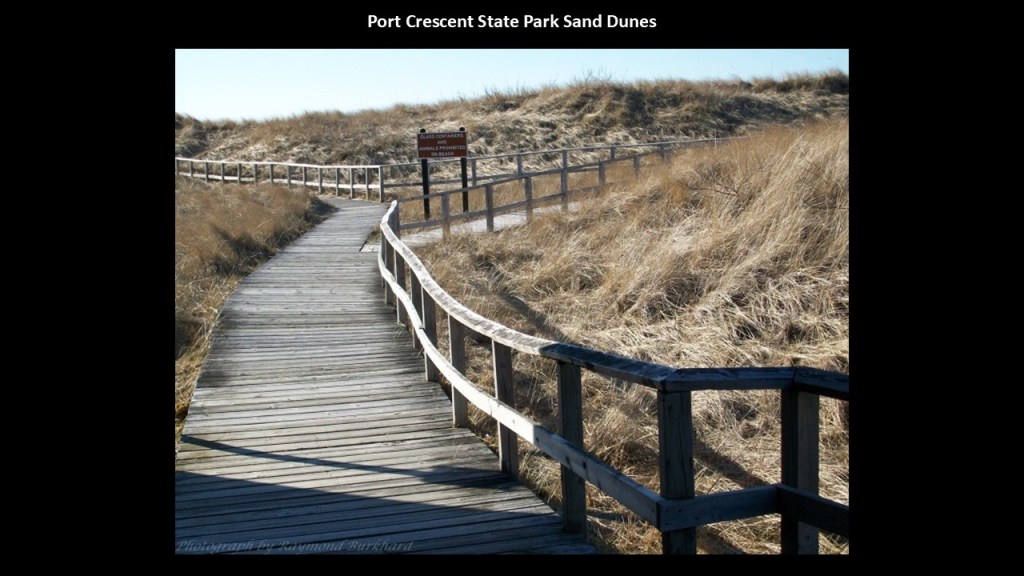

Port Crescent State Park is a public recreation area near Port Austin that occupeis the site of the former Port Crescent, ghost town which stood at the mouth of the Pinnebog River.

In 1961, the Pack & Woods Sawmill Chimney, one of the last visible remnants of Port Crescent, was demolished in spite of the objections of local residents.

Also, like the state parks we saw all around the shores of Lake Michigan, there are dunes here, and no, I don’t think these are natural either, as I believe a deliberate attack on the original free-energy grid system destroyed the surface of the Earth.

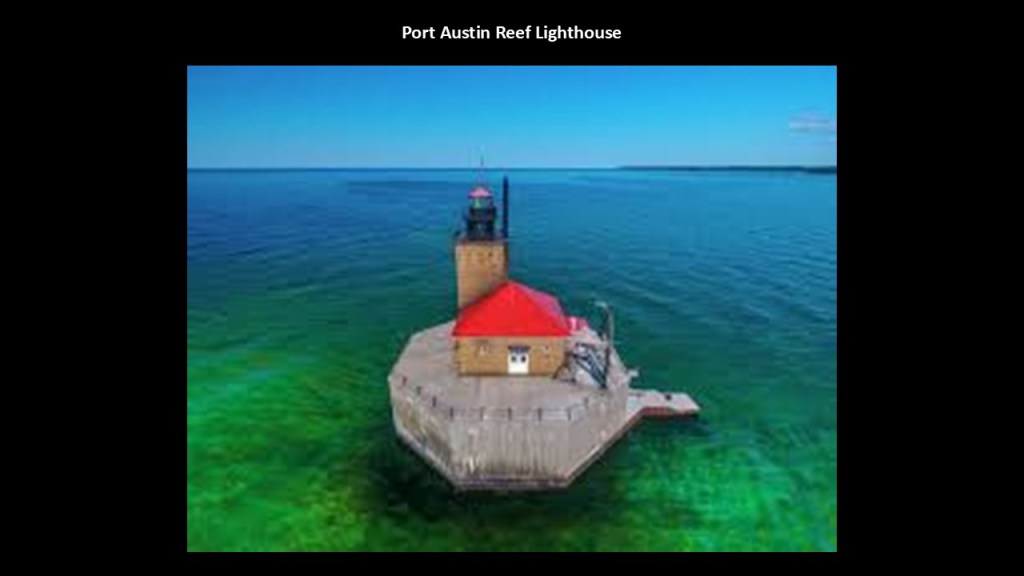

There are two lighthouses in close proximity to each other at the top of “The Thumb” – the Port Austin Reef Lighthouse and the Pointe au Barques Lighthouse.

The Port Austin Reef Lighthouse is located 2.5-miles, or 4-kilometers, north of Port Austin.

It is on a rocky shoal and considered a significant hazard to navigation.

The Port Austin Reef Lighthouse was said to have been constructed in 1878.

While there is an automated light in the lighthouse that is still operational, the lighthouse itself ihas been undergoing restoration for quite some time and is not open to the public.

Here is an historic photo of the Port Austin Reef Lighthouse on the left in comparison with the previously seen Forty Mile Point Lighthouse near Rogers City, and with which I also showed photos of other locations with the same architectural style, building orientation, and placement of the windows in Kansas; Tenerife in the Canary Islands; and Morocco.

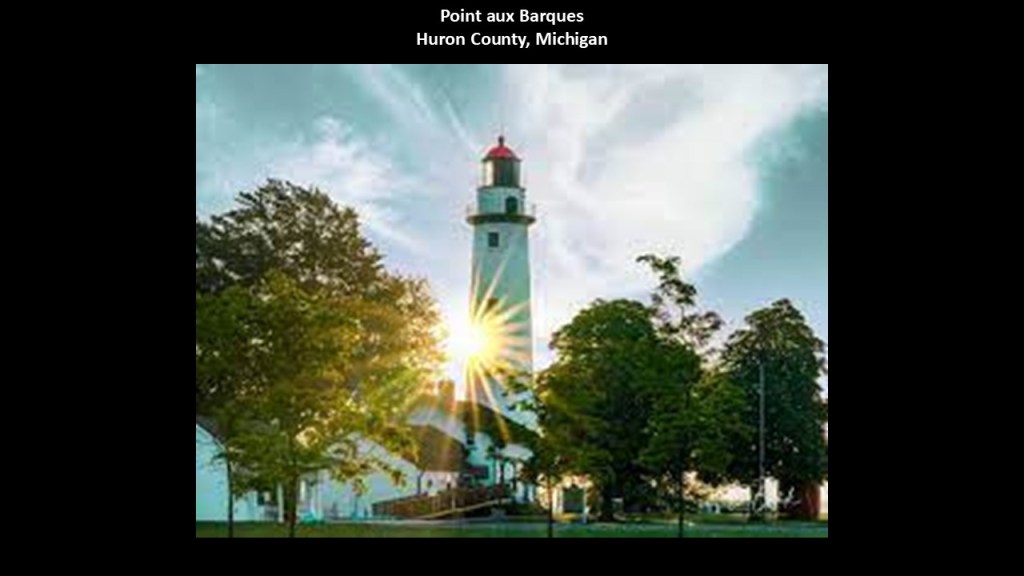

The Pointe au Barques Lighthouse today is an active lighthouse and maritime museum along the shores of Lake Huron on the northeastern tip of the Thumb.

The current structure was said to have been built in 1857.

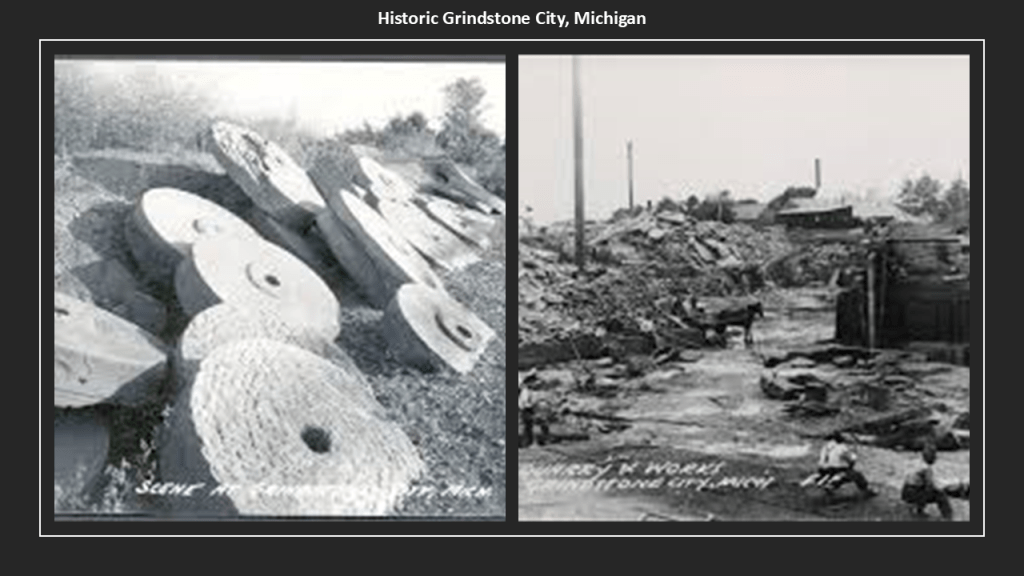

The last place I went to mention here before I move on down the Lake Huron coast is the interestingly-named Grind Stone City southeast of the Point aux Barques Lighthouse.

Grind Stone City is an unincorporated community in the eastern end of the Port Austin Township that was established in 1834.

It is the location of the Grind Stone City Historic District, which was listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1971.

In our historical narrative, we are told Grind Stone City was notable for a grindstone quarry that was established here sometime around 1833 by Captain Aaron G. Peer, who along with his brother, built a schooner for the Lake Transport business at the tip of Michigan’s “Thumb,” and by 1850, was selling $3,000 worth of grindstones a year.

The Lake Huron Stone Company and Cleveland Stone Company took over all operations in the area after a second quarry was opened.

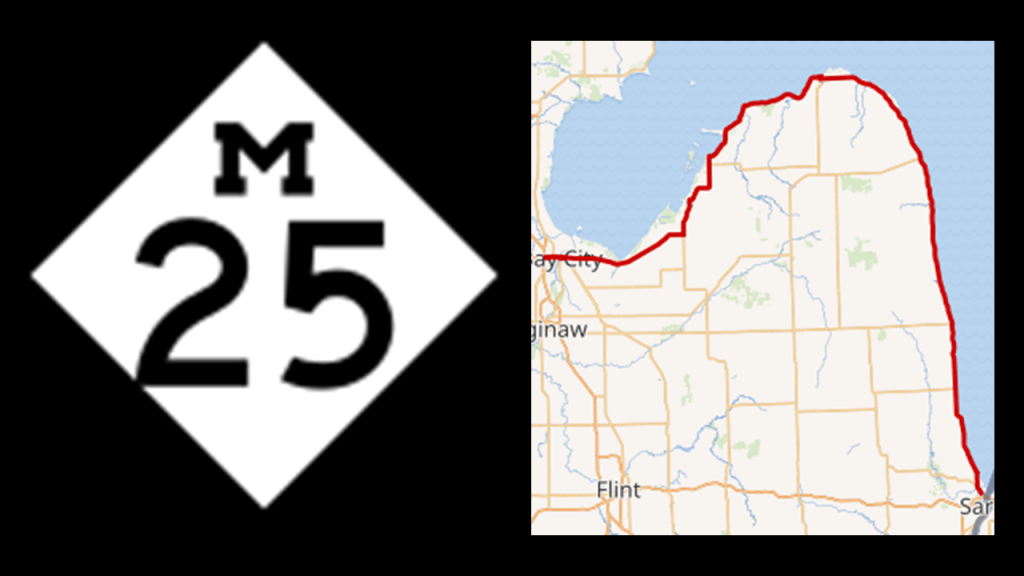

The Grind Stone City Historic District is located on Michigan State Trunkline Highway 25, which follows the arc-like shape closely along the Lake Huron shore of the Thumb between Port Huron and Bay City.

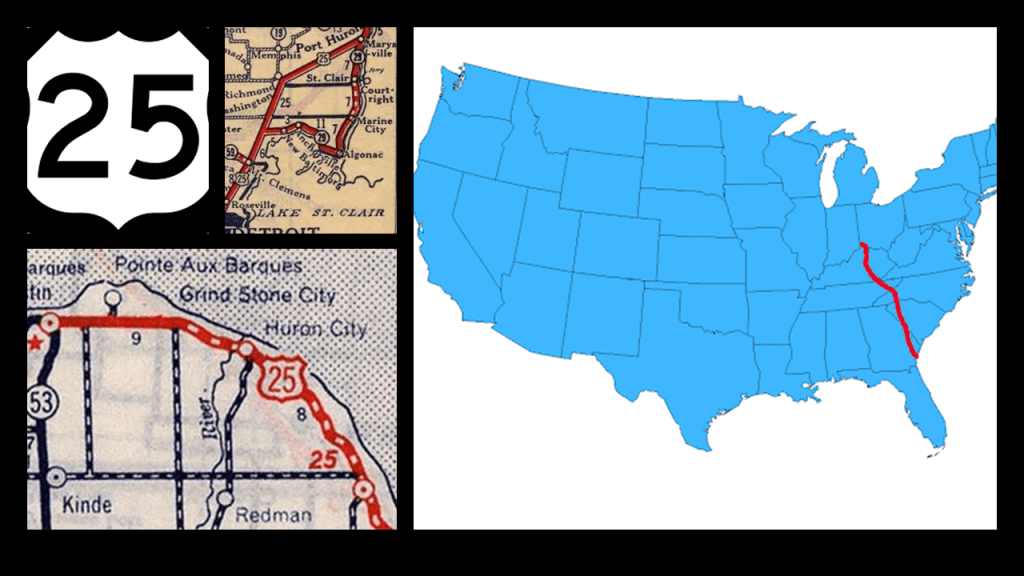

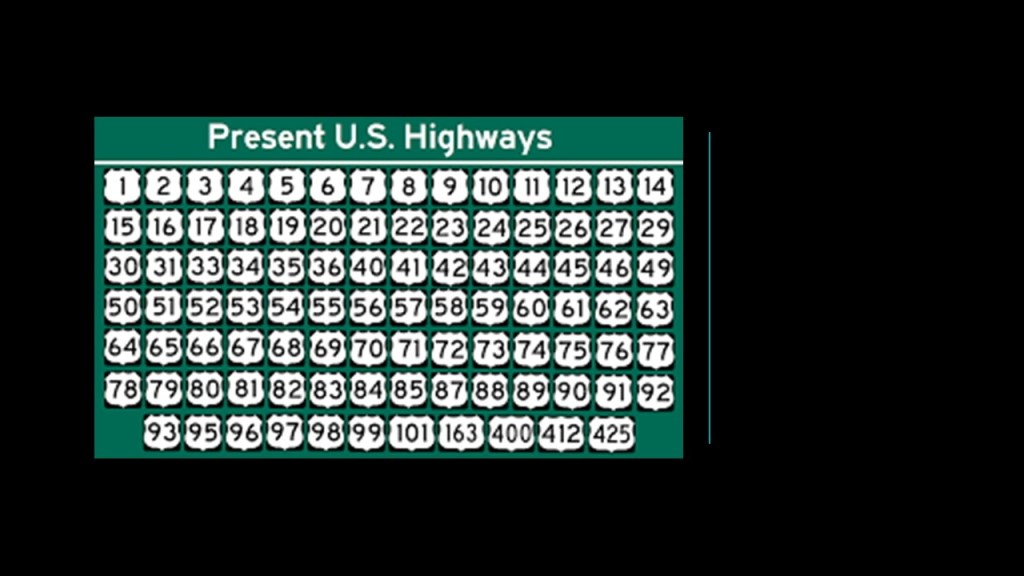

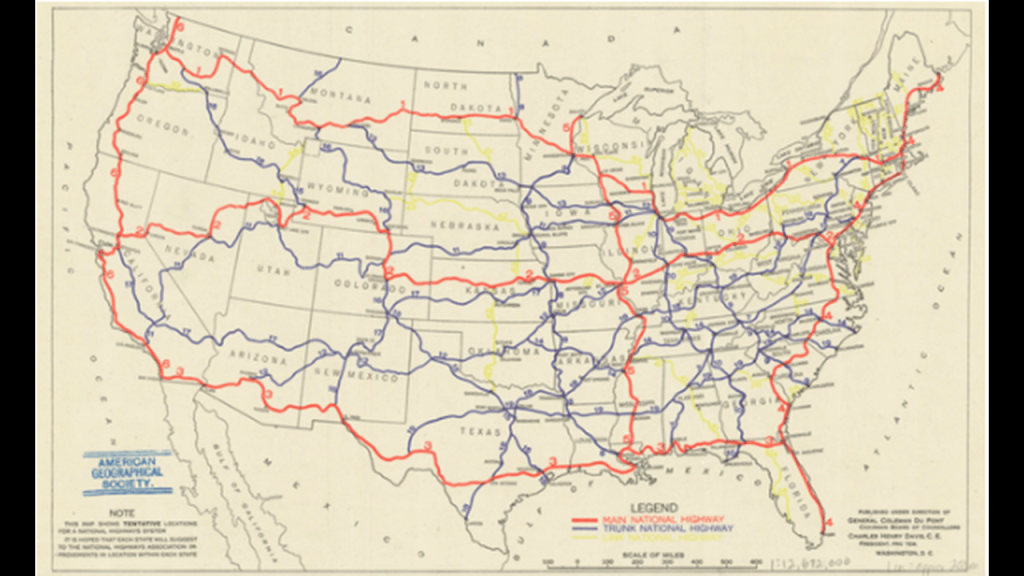

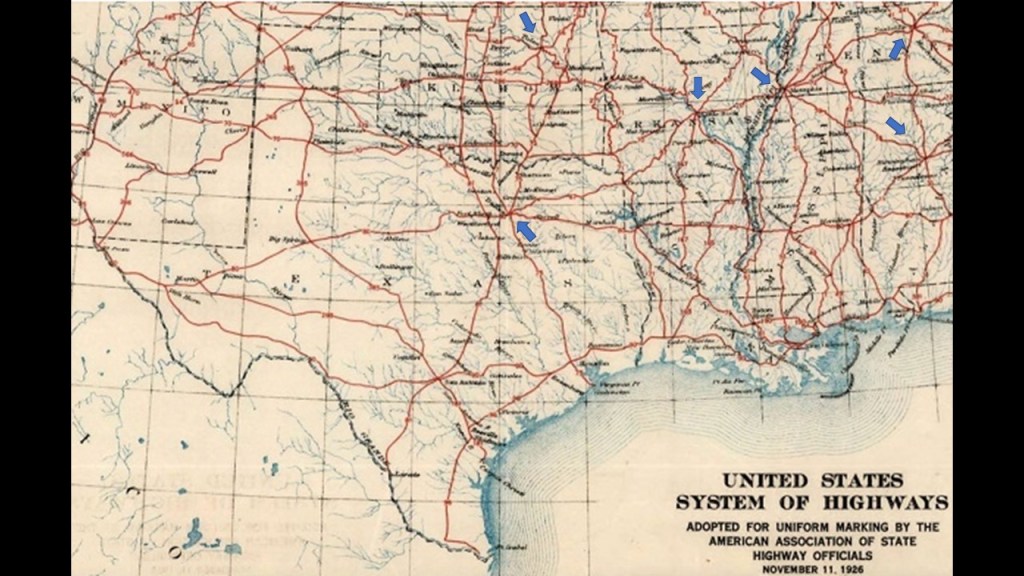

Michigan State Highway 25 was once part of the longer US Highway Route 25, when it was first established with the United States Numbered Highway System in 1926.

The original US-25 began at US Highway 17 in Brunswick, Georgia, and ended at Port Huron in Michigan, and was extended to Port Austin in 1933.