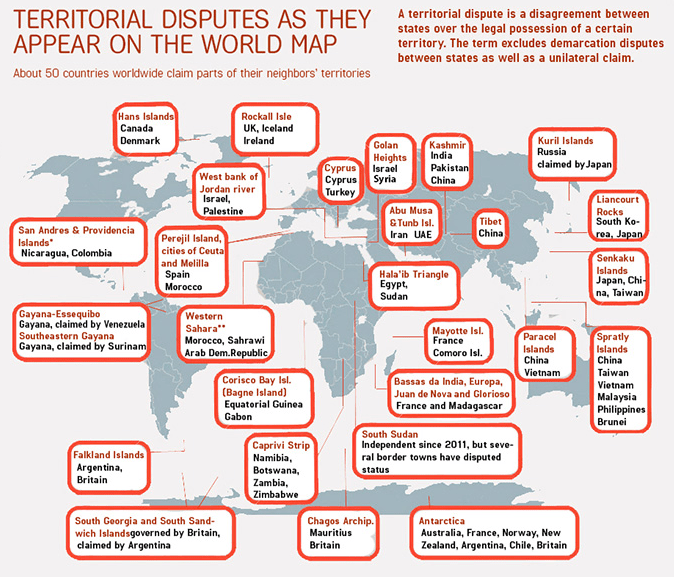

In my journey tracking cities and places in aligment with each other around the world, I kept coming across obscure, seemingly insignificant islands and island groups that are the subjects of territorial disputes between countries, many of which are still on-going in the present day.

I first published this post in October of 2019.

So I have been wondering about this for a very long time.

Now that I understand about the existence of Giant Trees with the help of Chad Williams of the “Deeper Conversations with Chad” YouTube channel, and their importance on the Earth’s grid system, I have a likely answer to the question posed in the title of this video…”What is it Exactly About the World’s Disputed Islands!”

In my latest conversation with Chad, “Giant Trees, the Earth’s Grid, and the New World Order,” among many other things, we talked about how the European Colonizers were going after tiny remote islands to claim for their countries.

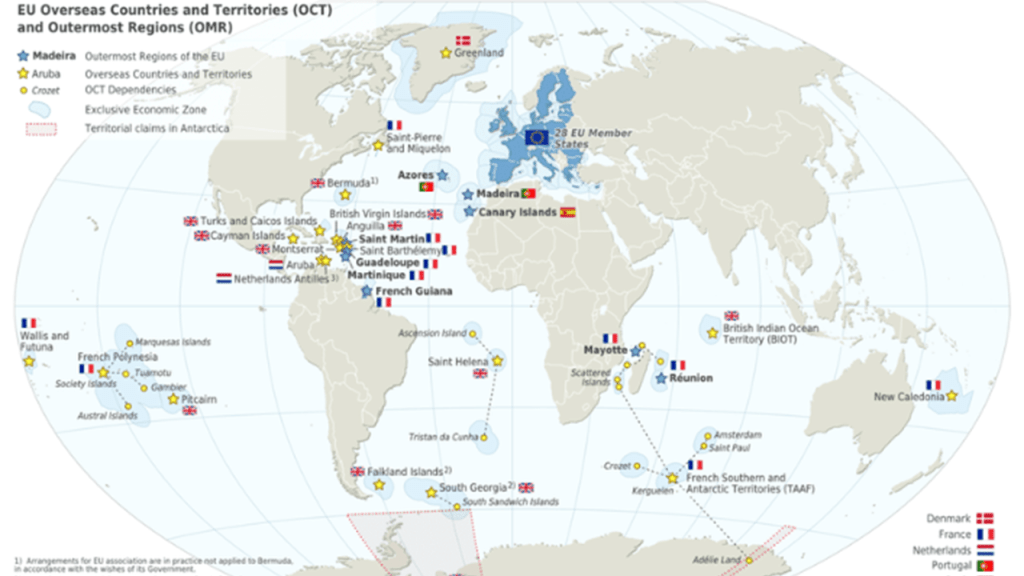

We discussed a number of these remote islands from the perspective that they were former giant tree locations, as I had come across many of these islands when tracking alignments that were claimed by different European Countries as “Overseas Countries, Territories and Outermost Regions.”

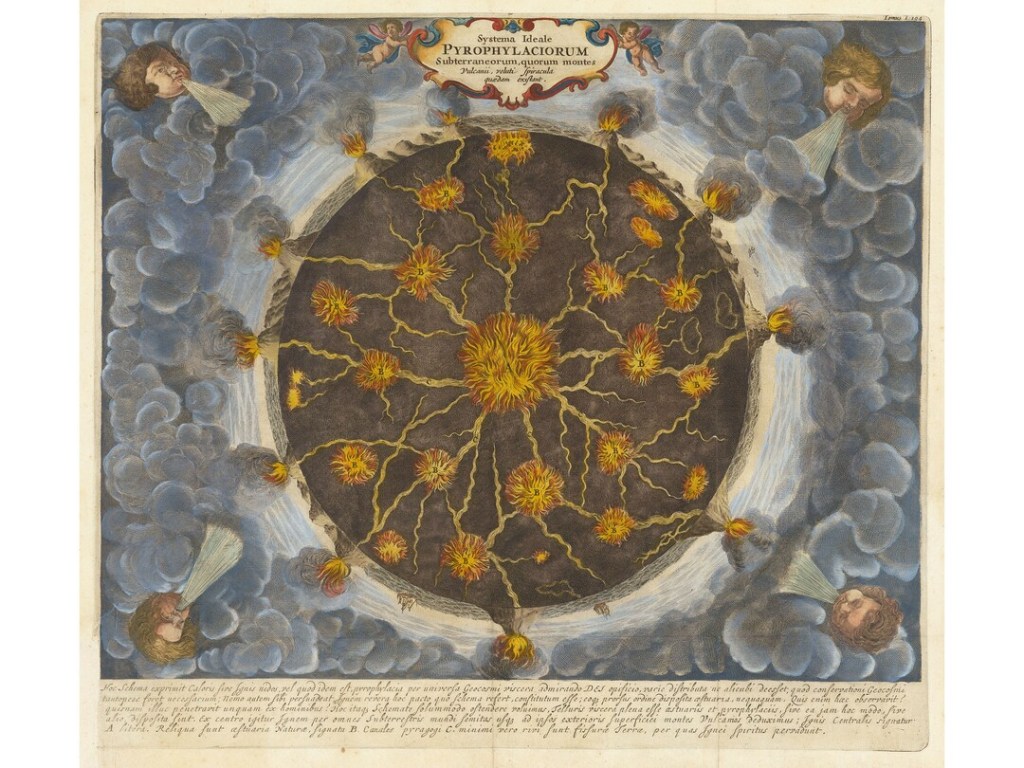

We also discussed this illustration that Chad found in his research that appears to depict volcanoes connected by a root system exploding simultaneously all over the Earth.

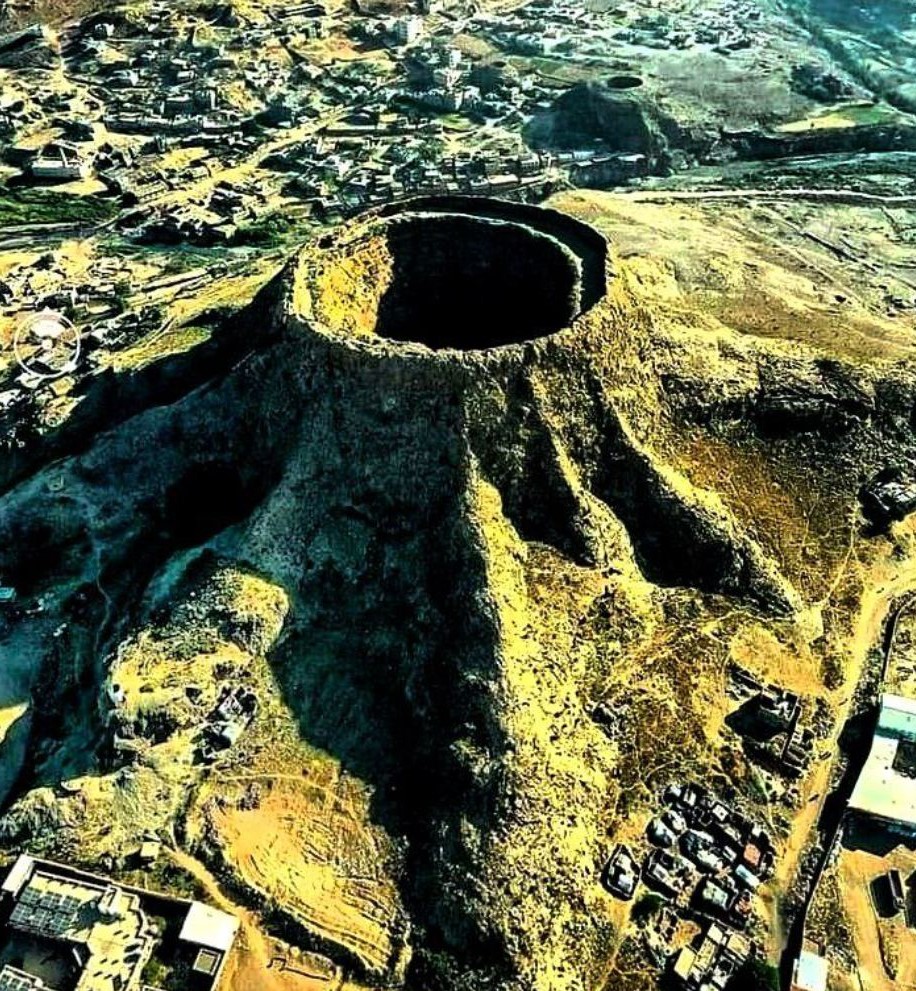

This could provide an explanation as to why the giant trees don’t look like trees any more, and are called by all manner of names, including “volcano.”

There apparently is a connection to volcanism with these giant trees that has been completely left out of our awareness, as seen in this photo of the tree-trunk-looking Harra of Arhab volcano in Yemen.

As I said at the beginning of this post, I also kept coming across obscure, seemingly insignificant islands and island groups that are the subjects of territorial disputes between countries, many of which are still on-going in the present day, in my journey tracking cities and places in alignment with each other around the world, and in many cases, the odd stories associated with these disputed islands.

I will start with the Spratley Islands.

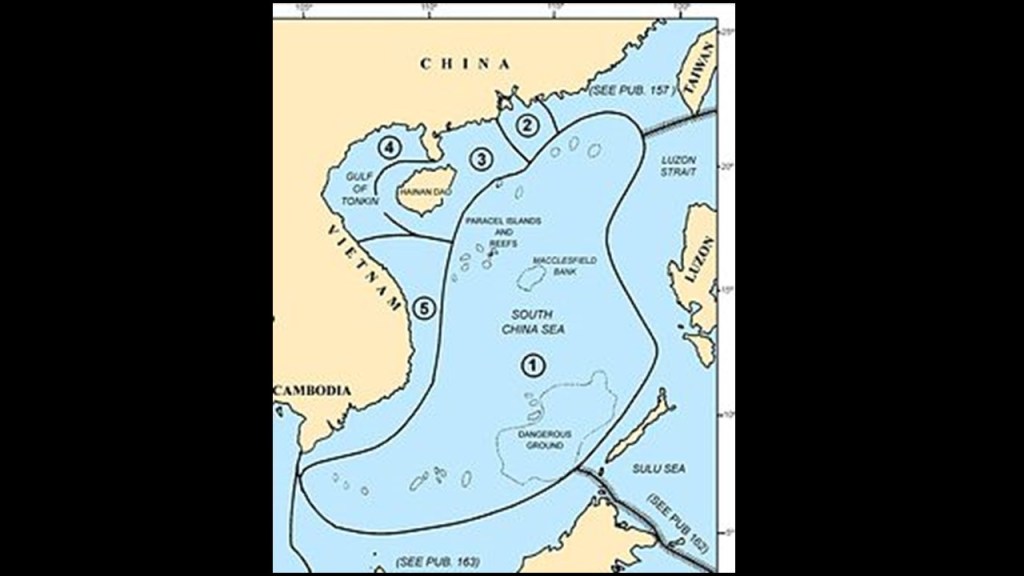

I found the Spratley Islands in the South China Sea when I was following one of the alignments that emanate off of the North American Star Tetrahedron at Merida, Mexico.

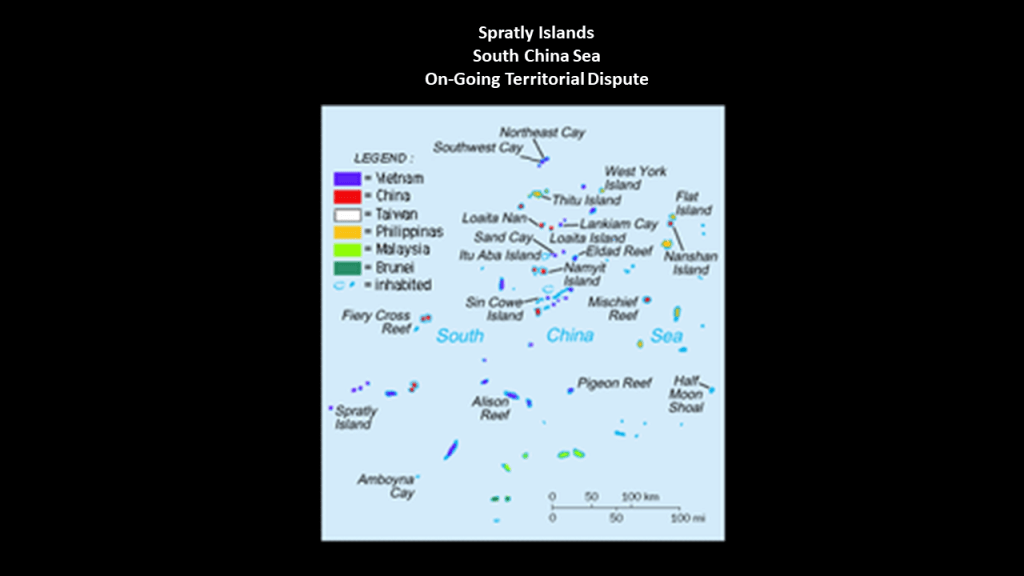

They consist of 14 islands or islets; 6 banks; 113 submerged reefs; 35 underwater banks; and 21 underwater shoals.

The northeast part of the Spratlys is known as dangerous ground due to low islands; sunken reefs; and degraded sunken atolls.

They are located on the alignment just northwest of Palawan Island…

…and Palawan, in the Philippines, is considered by many to be the most beautiful island in the world.

There is a star fort located in Taytay on the island of Palawan called the Fuerza de Santa Isabel.

From my extensive research on the physical lay-out of earth-grid alignments, and the frequent occurrence of star forts situated along the Earth grid system worldwide, I believe that star forts functioned as batteries on the Earth’s grid system, and were not originally military in nature as we have been led to believe in our historical narrative.

Back to the Spratley Islands.

The Spratly Islands dispute is an on-going territorial dispute between China, Taiwan, Malaysia, the Philippines, Brunei and Viet Nam concerning “ownership” of the Spratly Islands.

What is it about these islands?

Well, we are told they are of economic and strategic importance; hold reserves of natural gas and oil; productive fisheries; and is a busy area for commercial shipping traffic.

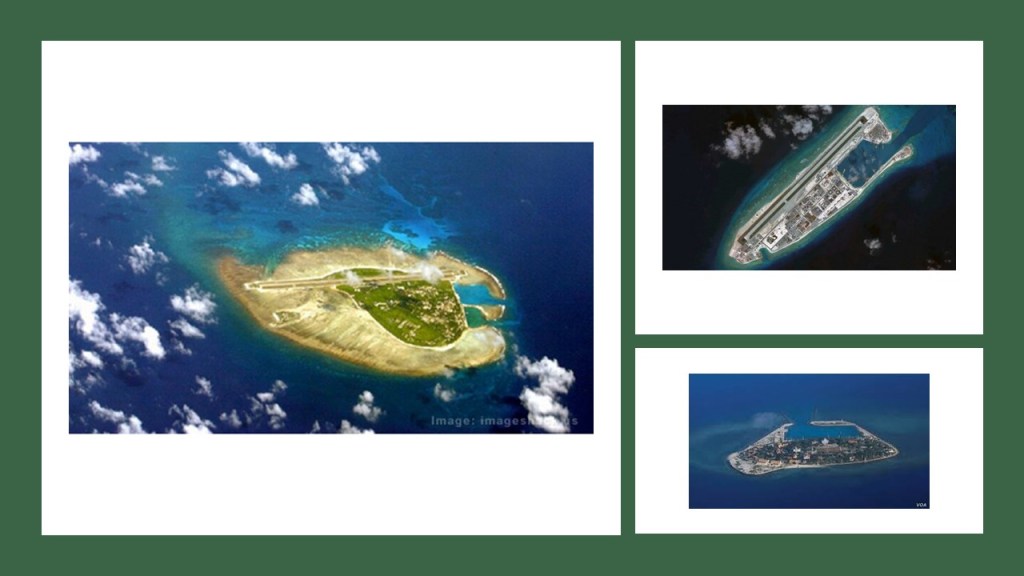

At the time I originally did the research for this post, I speculated that there is a powerful energy component here–whether placement, production, or something else–related to the Earth’s grid lines, and it is becoming clearer and clearer that the giant trees of the Earth were powerful components of the Earth’s grid system.

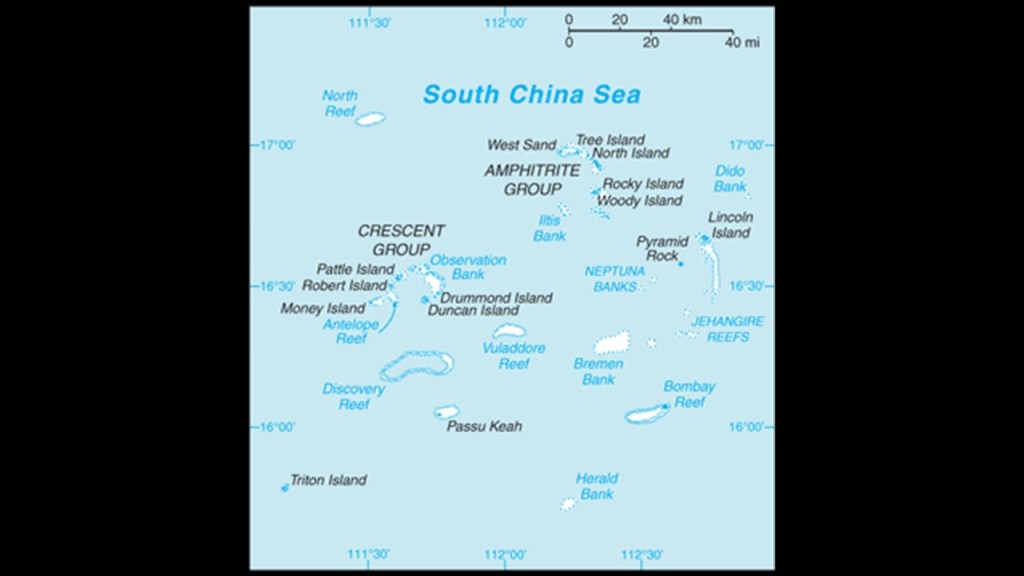

So, for another example of this in the South China Sea, just northwest of the Spratly Islands on the same alignment’s way through Hainan in China, the Paracel Islands are a similar group of islands, reefs, and banks that are strategically located; productive fishing grounds; and which also hold reserves of natural gas and oil.

While they are controlled and operated by China, they are also claimed by Taiwan and Viet Nam.

The archipelago consists of 130 small coral islands and reefs, most grouped into the northeast Amphitrite Group or the western Crescent Group.

Island names suggestively include: Tree Island; Woody Island; Pyramid Rock; and Money Island.

In ancient Greek mythology, Amphitrite was a sea goddess; the wife of Poseidon; and the Queen of the Sea.

The Paracel Islands are also the location of the Dragon Hole, or Sasha Yongle Blue Hole, the world’s deepest known blue hole at 987-feet, or 301-meters, deep.

Former giant tree location perhaps?

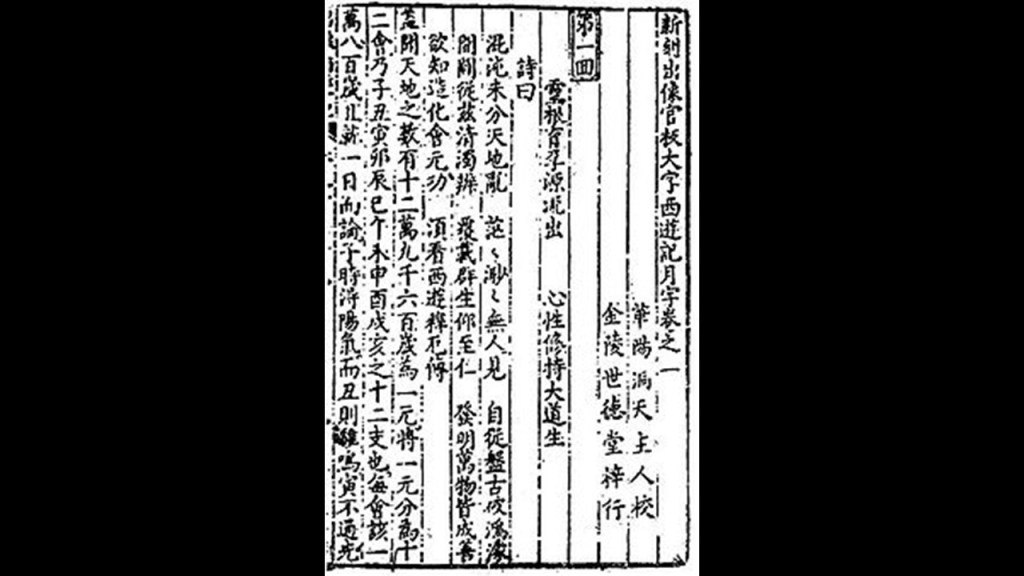

Dragon Hole is called the “Eye of the South China Sea,” and is where the Monkey King found his golden cudgel in the 16th-century Chinese classic of Literature “Journey to the West,” with authorship attributed to Wu Cheng’en.

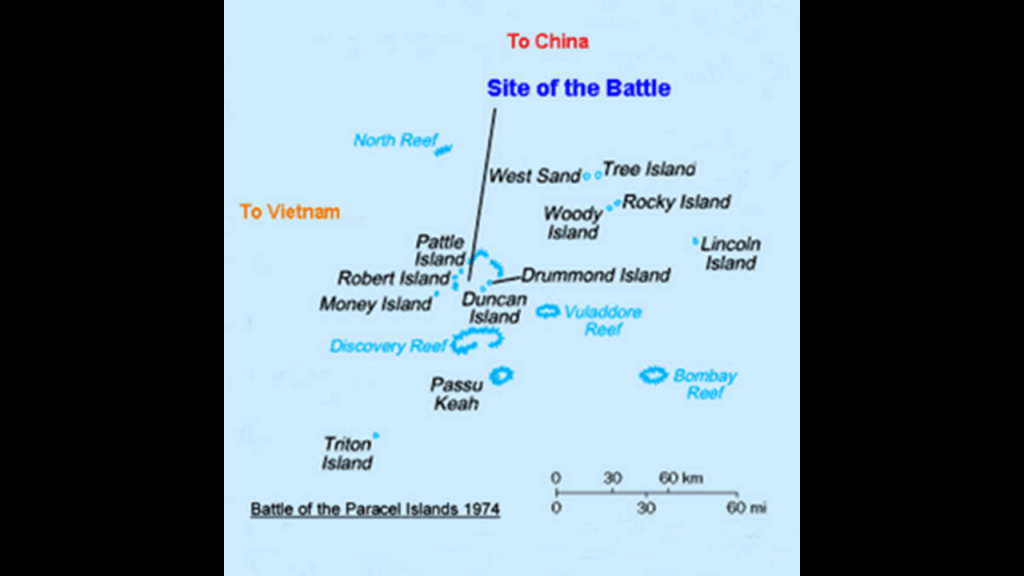

The Battle of the Paracel Islands was a military engagement between the naval forces of South Vietnam and China in 1974, and was an attempt by the South Vietnamese navy to expel the Chinese navy from the vicinity.

As a result of the battle, China established de facto control over the Paracel Islands.

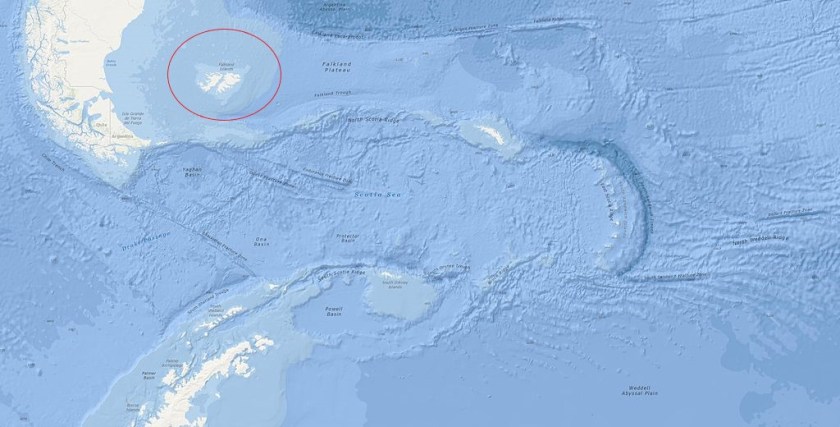

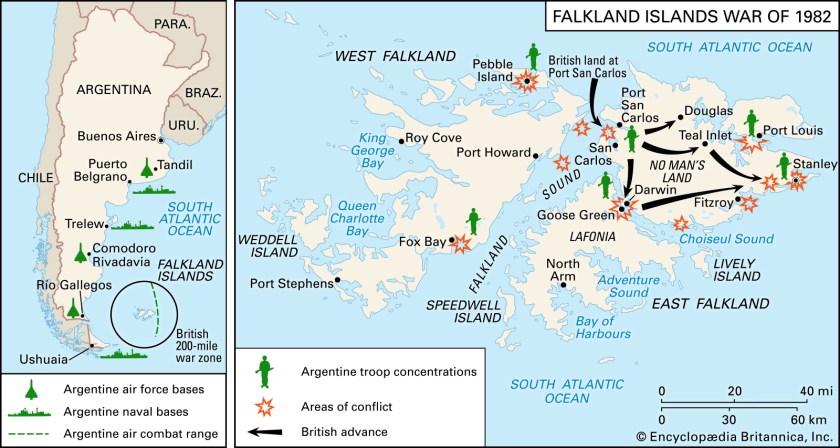

The next place that I am going to look at are the Falkland Islands, an archipelago in the South Atlantic Ocean on the Patagonian Shelf.

They are 300-miles, or 483-kilometers, east of South America’s southern Patagonian coast, and 752-miles, or 1,210-kilometers, from the northern tip of the Antarctic Peninsula, at a latitude of 52-degrees south.

It is a British overseas territory, and consists of two large islands – East Falkland and West Falkland – and 776 smaller islands.

The population of less than 4,000 people are British citizens.

Britain reasserted its rule over the Falklands in 1833, with a colonial presence also including French, Spanish, and Argentine settlements.

Argentina maintains its claim to the islands.

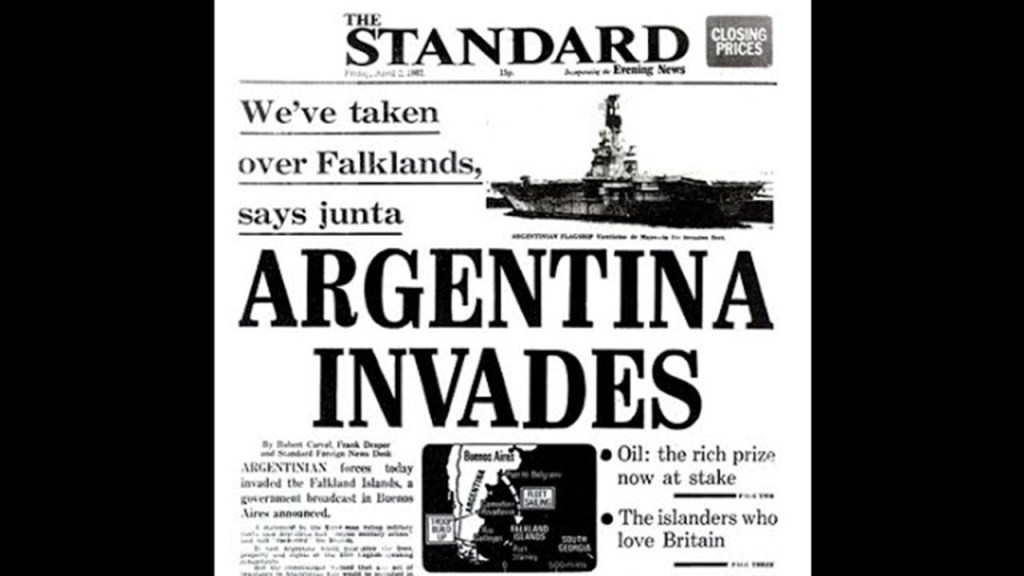

On April 2nd, 1982, Argentine forces occupied the Falkland islands.

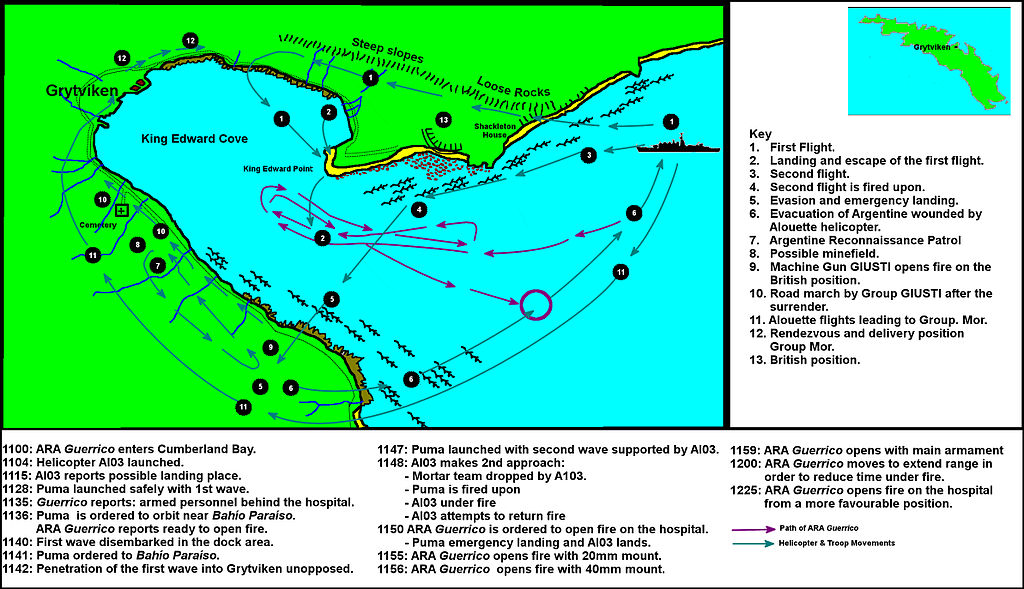

On April 3rd, 1982, Argentine forces seized control of the east coast of South Georgia Island in the Battle of Grytviken, part of the South Sandwich Islands, and another British Overseas Territory near the Falkland Islands that is claimed by Argentina.

On April 5th, 1982, the Falklands War between Argentina and Great Britain started. While not officially declared a war, it was declared a war-zone.

The conflict lasted 74-days, and ended with Argentina’s surrender on June 14th, 1982, returning the islands to British control.

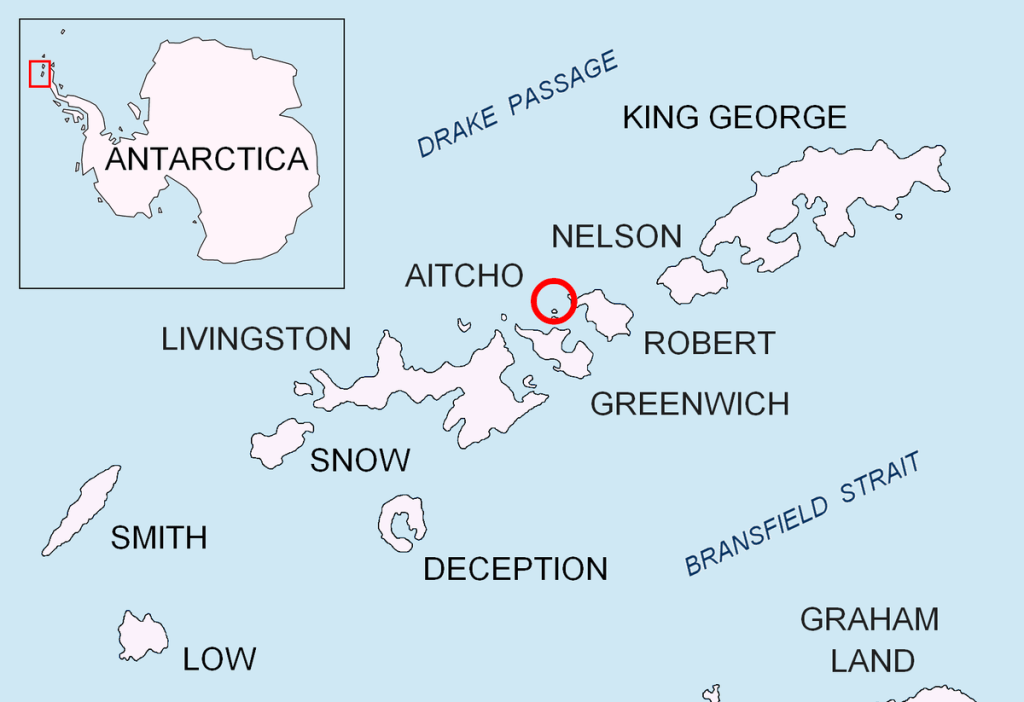

The South Shetland Islands shown here in this map are in the neighborhood of all these little island groups off the southernmost tip of South America, and are a group of Antarctic islands with a total area of 1,424 square-miles, or 3,687 square-kilometers.

By the Antarctic Treaty of December 1st, 1959, the islands’ sovereignty is neither recognized nor disputed by the treaty’s 12 signatories – Argentina, Australia, Belgium, Chile, France, Japan, New Zealand, Norway, South Africa, the Soviet Union, the United Kingdom, and the United States – and they are free for use by any signatory for non-military purposes.

However, the islands have been claimed by Great Britain since 1908, and as part of the British Antarctic Territory since 1962.

They have also been claimed by Chile and Argentina since the 1940s.

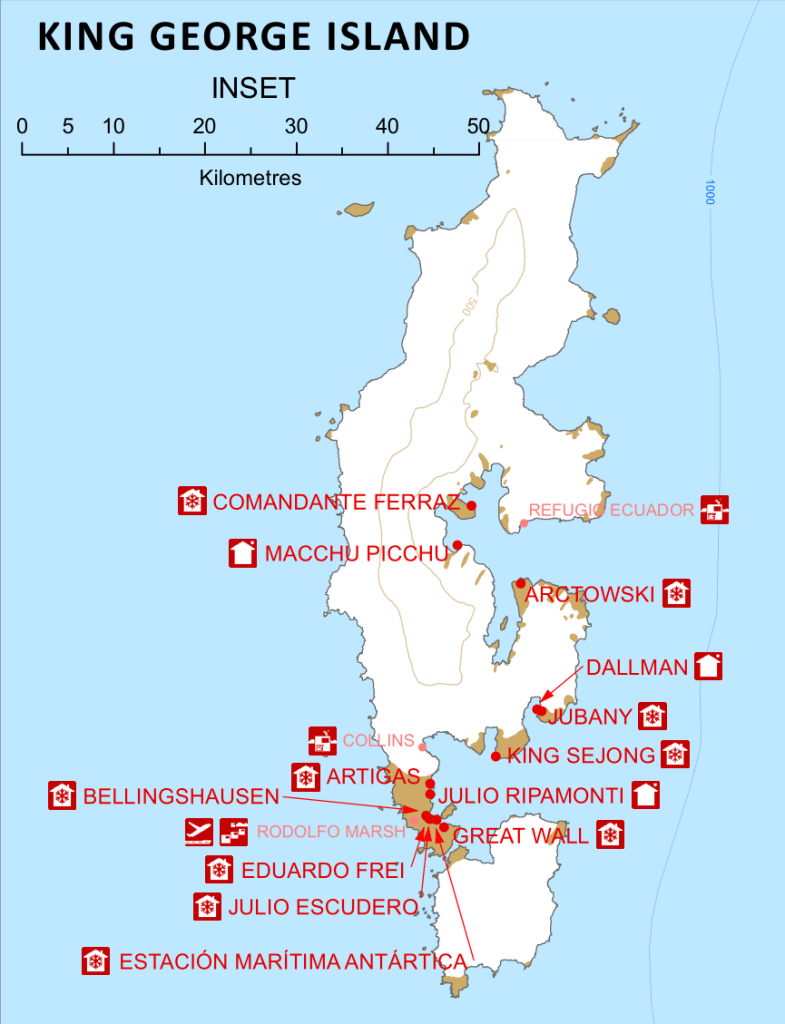

The Chileans have the largest number of research stations on the islands, as well having the Eduardo Frei airbase on King George Island, where the largest number of international research stations are located.

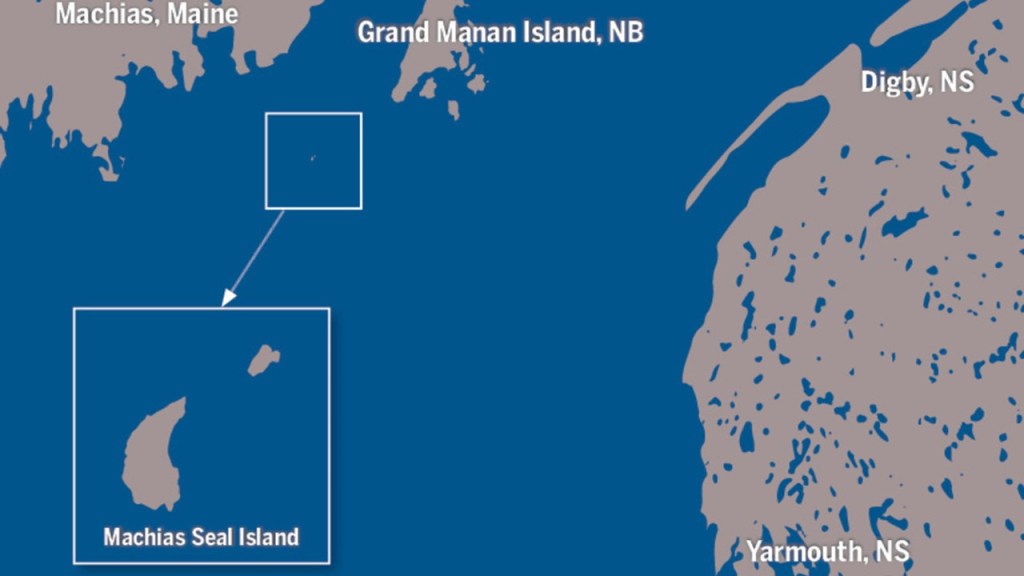

Moving to North America in the northern hemisphere, Machias Seal Island, which has a lighthouse in the center of it manned by the Canadian Coast Guard, is part of an on-going territorial boundary dispute between the United States and Canada.

Machias Seal Island is located on the border of the Gulf of Maine in the United States, and the Bay of Fundy in Canada.

Other boundary disputes, not limited to islands, between the United States and Canada include:

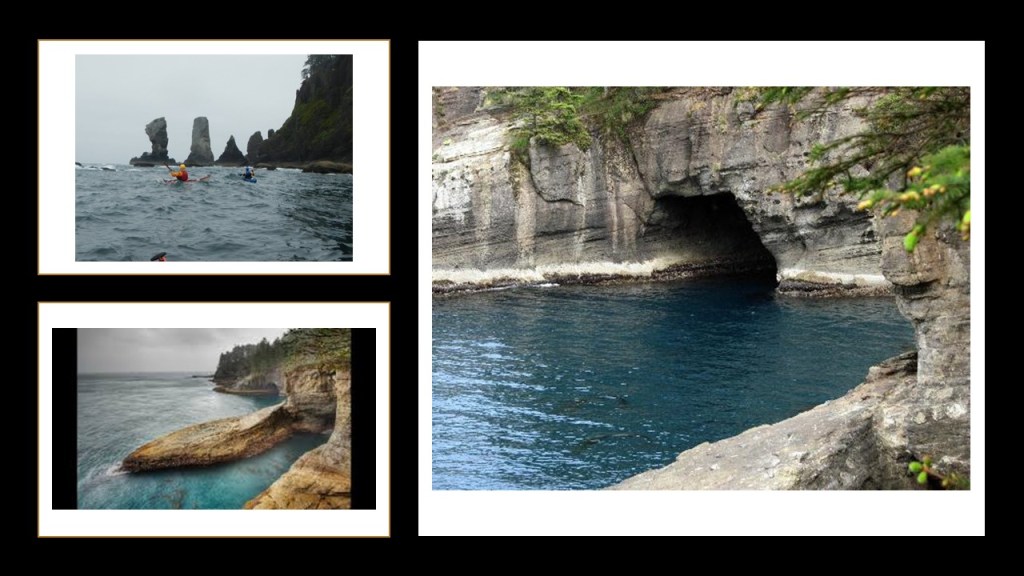

A fishing zone dispute at the mouth of the Juan de Fuca Strait between Washington State and British Columbia, and within which the International boundary between the two countries lies in the middle of the strait.

Here are photographs of what Cape Flattery looks like at the mouth of the Juan de Fuca Strait on Washington’s Olympic Peninsula.

Another area of dispute between the two countries is the Northwest Passage, which Canada claims as part of its internal waters, and the United States regards as an international strait, open to international traffic.

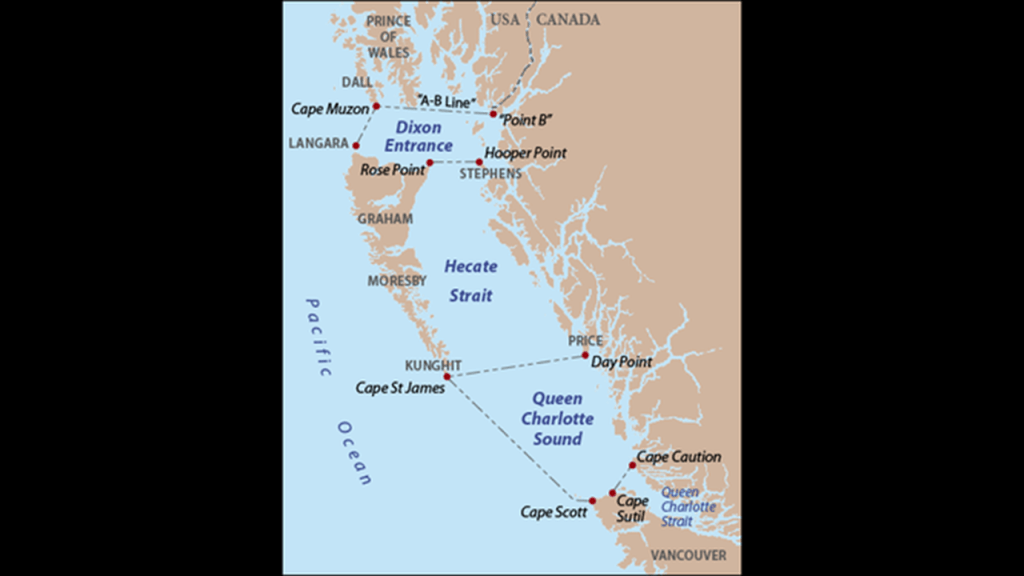

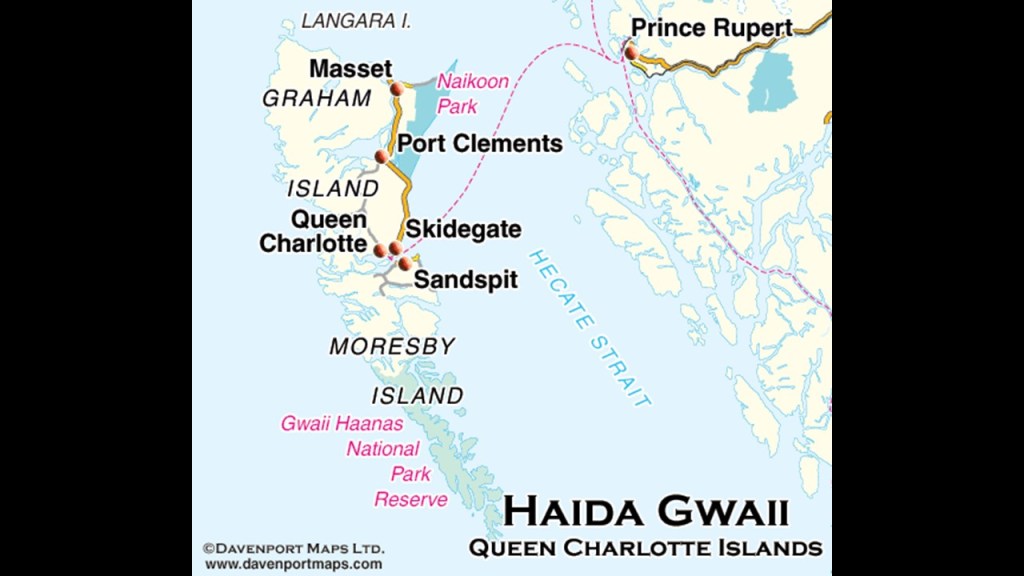

The Dixon Entrance, a strait about 50-miles, or 80-kilometers, long, between Alaska in the United States and British Columbia in Canada is also mutually claimed by both countries.

It is part of the Inside Passage shipping route.

It lies between the Clarence Strait in the Alexander Archipelago, a 300-mile, or 480-kilometer, long group of islands in Alaska to the North…

…and the Hecate Strait and the islands known as the Haida Gwaii (or Queen Charlotte Islands) in British Columbia to the South.

Members of the Haida Nation maintain free access across the strait, in the Haida Gwaii and islands in the Alaskan Panhandle where they have said to have lived for 14,000 years.

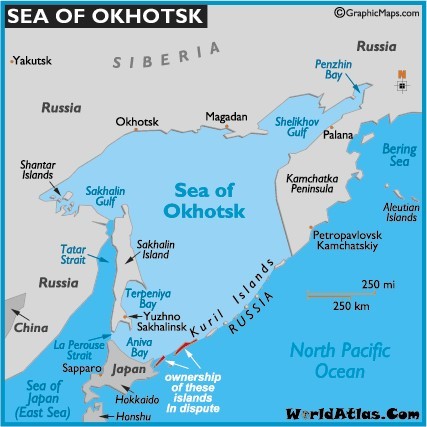

Next, the Kuril Islands dispute is a disagreement between Japan and Russia over the sovereignty of the four southernmost Kuril Islands.

They are a chain of islands stretching between the Japanese Island of Hokkaido at the southern end, and the Kamchatka Peninsula at the northern end.

While the San Francisco Peace Treaty of 1951, signed between the Allies and Japan in 1951, stated that it must give up all right, title and claim to the Kuril Islands, Japan does not recognize Russia’s sovereignty over them, and this territorial dispute has not been resolved.

The original inhabitants of the Kuril Islands, and northern Japan for that matter, are the Ainu, as seen here in 1904…

…and today.

Other disputed islands around the world include:

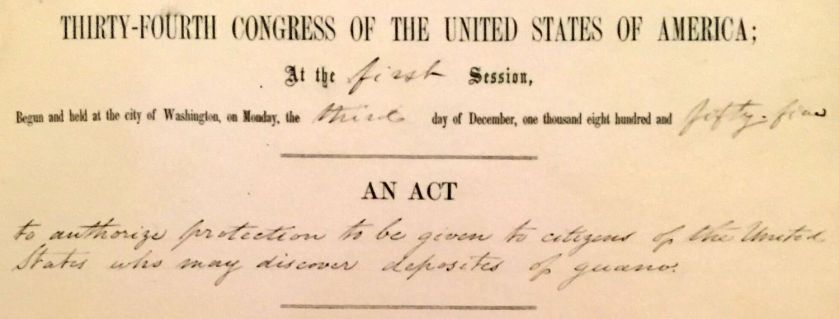

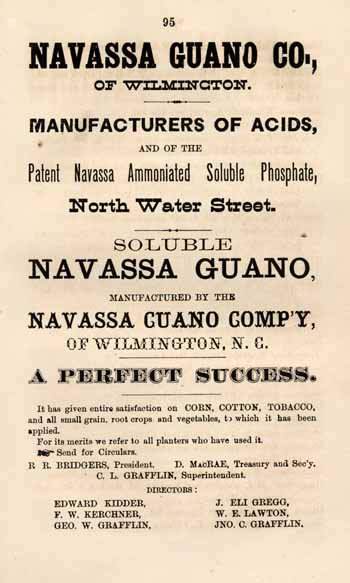

Navassa Island, an uninhabited island in the Caribbean Sea.

This small island is subject to an on-going territorial dispute between the United States and Haiti.

The United States claimed the island since 1857, based on the Guano Islands Act of 1856.

The legislation essentially said that an American could claim an uninhabited, unclaimed island, if it contained guano, or bird droppings, which was an effective early fertilizer.

Haiti’s claims over Navassa go back to the Treaty of Ryswick in 1697, which established French possessions in mainland Hispaniola that were transferred from Spain by the treaty.

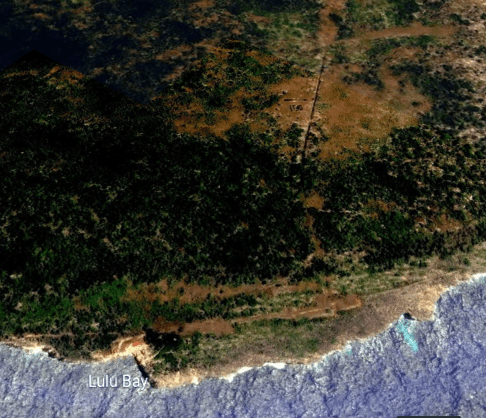

This is the deactivated lighthouse on Navassa. This is the only building left of what was previously on Navassa Island…

…possibly including this star fort identified as being in Lulu Town on Navassa, but I can’t confirm this finding because whatever was there isn’t there any more.

Lulu Town was previously situated around Lulu Bay on Navassa Island.

Abu Musa is a 5-square-mile, or 13-square-kilometer, island in the eastern Persian Gulf near the entrance to the Strait of Hormuz.

Abu Musa is administered by Iran as a part of its Hormozgan Province, but it is also claimed by the United Arab Emirates as a territory of the Emirate of Sharjah.

I found the island of Abu Musa, one of the islands of the Strait of Hormuz, when I was tracking the Amsterdam Island Circle Alignment.

On to Cyprus, an island country in the eastern Mediterranean, located south of Turkey, and west of Syria and Lebanon, northwest of Israel and Palestine, north of Egypt, and southeast of Greece.

Based on the Cyprus Convention in 1878, Cyprus was placed under the United Kingdom’s administration, and formally annexed by the United Kingdom in 1914 (which would have been around the time of the start of World War 1).

While Turkish Cypriots made up 18% of the population, the partition of Cyprus and creation of a Turkish state in the north became a policy of Turkish Cypriot leaders and Turkey in the 1950s.

Turkish leaders for a period advocated the annexation of Cyprus to Turkey as Cyprus was considered an “extension of Anatolia” by them; while, since the 19th century, the majority population of Greeks on Cyprus and its Orthodox Church had been pursuing union with Greece, which became a Greek national policy in the 1950s.

After nationalist violence in the 1950s, Cyprus was granted independence in 1960 via the London and Zurich Agreements of 1959.

At any rate, conflict in one form or another between Greeks and Turks has existed on the island for awhile, with the island partitioned between the two.

Regardless, Cyprus is a major tourist destination in the Mediterranean today.

It’s important to note that the island of Cyprus shares the name of a tree, pronounced phonetically the same, though spelled differently.

So while we are told, no, they are not the same, there are in fact, cypress trees on Cyprus, and they are native to Cyprus.

The “Frank Cypress” in Nisou, is said to be 500-years-old, in existence since the time of Frankish rule there, is one of the tallest cypress trees on the island today, at 28-meters-, or 92-feet, -tall, and 4.5-meters, or 15-feet, -wide.

Also important to note that Cypress wood was used in the building of Solomon’s Temple.

There seems to be a lot more to find here about ancient giant trees in general on Cyprus, but let’s just say they are revered here.

Just a couple of more places to look at.

Tromelin Island is a low, flat island in the Indian Ocean.

Besides being a seabird and sea tortoise sanctuary, the only structure here is a meteorological station used to gather data in order to forecast hurricanes and cyclones.

It is located 310-miles north, or 500-kilometers, north of Reunion Island, and 280-miles, or 450-kilometers, east of Madagascar.

It is administered as part of the French Southern and Antarctic Lands as a French overseas territory, however, the island nation of Mauritius claims sovereignty over the island.

I found both Mauritius and Tromelin Island on earth-grid alignments.

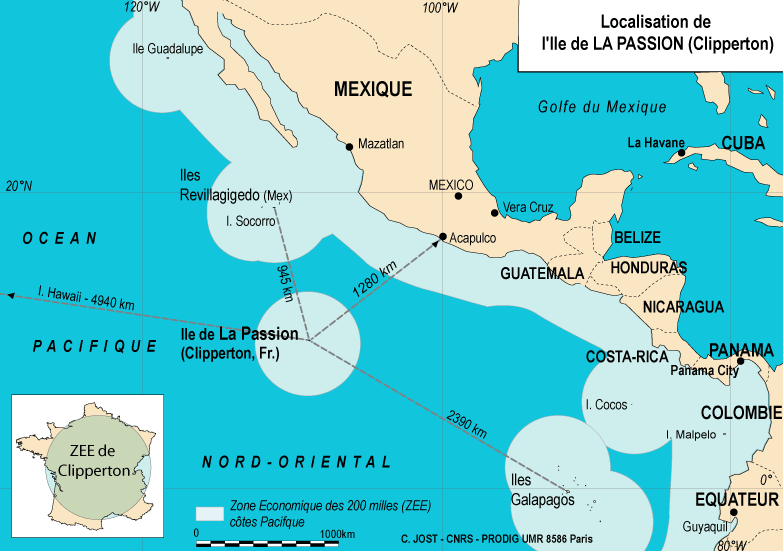

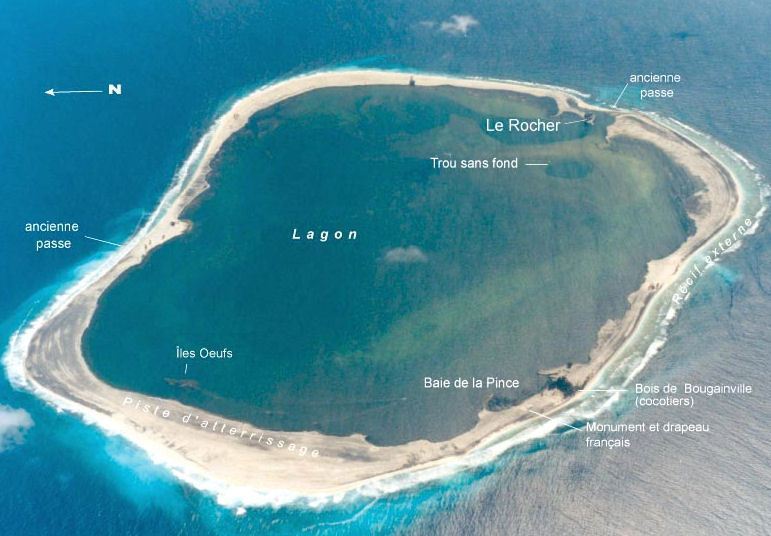

The last place I want to include in this post is Clipperton Island, an uninhabitated 2-square-mile, or 6 kilometer-squared island, in the eastern Pacific Ocean off the coast of Central America.

While it is not disputed now, it has been in the past.

It is an overseas minor territory of France, and administered under the direct authority of the Minister of Overseas France.

It has not been inhabited since 1945, though it is occasionally visited by fisherman, French Navy patrols, scientific researchers, film crews, and ham radio operators.

It is low-lying, and largely barren.

The surrounding reef is exposed at low tide.

Two Frenchmen first claimed the island for France in 1711, and named it “Ile de la Passion.”

In 1858, during France’s Second Empire, Emperor Napoleon III annexed Clipperton island as part of the French colony of Tahiti, even though it is the considerable distance of 3,400 miles, or 5,400 kilometers, from Tahiti.

It was named Clipperton for English pirate and privateer John Clipperton who fought for the Spanish in the early 18th-century who may have used it as a base for his raids on shipping.

Other claimants included the United States, whose American Guano Company claimed it, like Navassa Island, under the Guano Islands Act of 1856…

…and Mexico due to its activities there as early as 1848 and 1849.

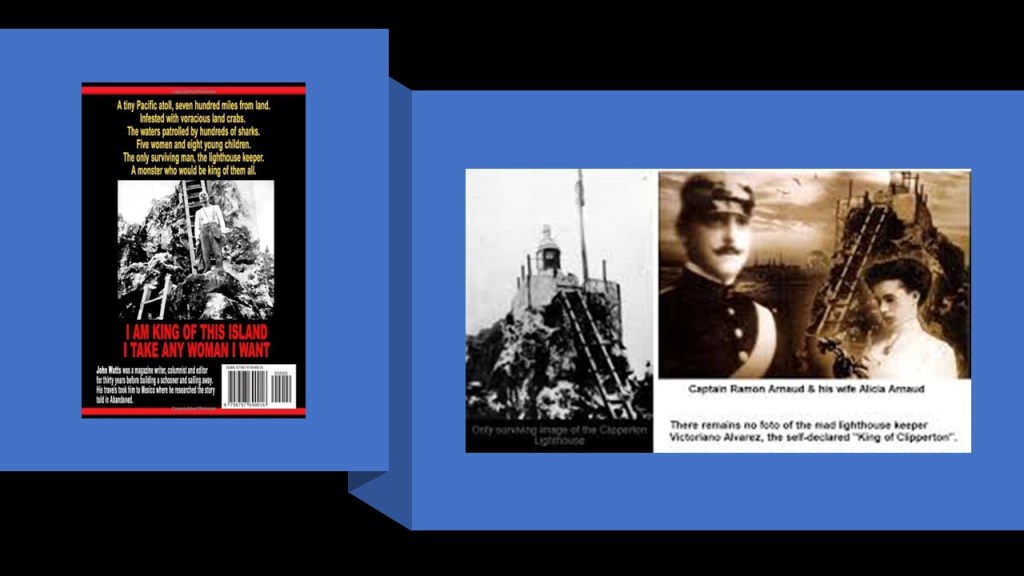

It also has a lurid and bizarre history of its own from its days as part of Mexico.

In 1909, France and Mexico agreed to submit the dispute over sovereignty to binding international arbitration, and 22-years later, in 1931, the King of Italy, Victor Emmanuel III, issued the final decision, declaring Clipperton Island to be a French possession.

However, after all of this territorial interest, Clipperton Island has been more or less abandoned since the end of World War II.

So, as expressed in the title of this post, there is something about the world’s disputed islands that make them desirable possessions worth fighting over.

As you can see from the locations mentioned in this post, these are mostly obscure, seemingly insignificant islands and island groups that are the subjects of territorial disputes between countries, most of which are still on-going in the present day.

There are many other examples of territorial disputes, but these are enough to give you the idea with regards to disputed islands.

I definitely think it’s significant that these little islands and island groups figure prominently on the Earth’s gridlines, and that there is much more to the story we are not being told, especially with regards to the once-existence of giant trees on Earth that were integral to the Earth’s grid system.

All of these islands are viewed as highly-coveted prizes, and as a critical part to nation-building plans.

The reason has been deliberately hidden from our view as to “What is it Exactly About the World’s Disputed Islands?”

10/24/23

Your work is excellent and I would like to donate. I want to send a check. Can you provide a mailing address for me. Thank you, Margaret

LikeLike

Hi Margaret ~ I really appreciate your feedback and support! My mailing address is: P. O. Box 4772, Sedona, AZ, 86340. In gratitude, Michelle

LikeLike

Thank you for responding, Michelle. I made the request a year ago, also and when I didn’t receive a response I felt sad. Your work is so profound that I want to express my gratitude. I don’t donate on sites that inhibit free speech.

LikeLike

Thank you, Margaret! I try to stay on top of everything, but am not always able to do that! I get busy and things get away from me sometimes. Peace and many blessings to you! Michelle

LikeLike

Would continental drift have an affect on such a grid. Places slowly moving out of alignment disturbing the field.

LikeLike

I am sure many factors affect the grid. It is electromagnetic nature.

LikeLike