There’s some kind of functional connection on the Earth’s original grid system between gorges, waterfalls, rapids, railroads, dams & reservoirs, bridges, canals, star forts, highways…and likely places where there were once giant trees.

The Controllers have also done a lot to destroy the evidence or hide it as much as they can, but the evidence is still there to find if you know where to look and how to interpret it.

The purpose of this blog post is to provide you with compelling evidence to support this assertion.

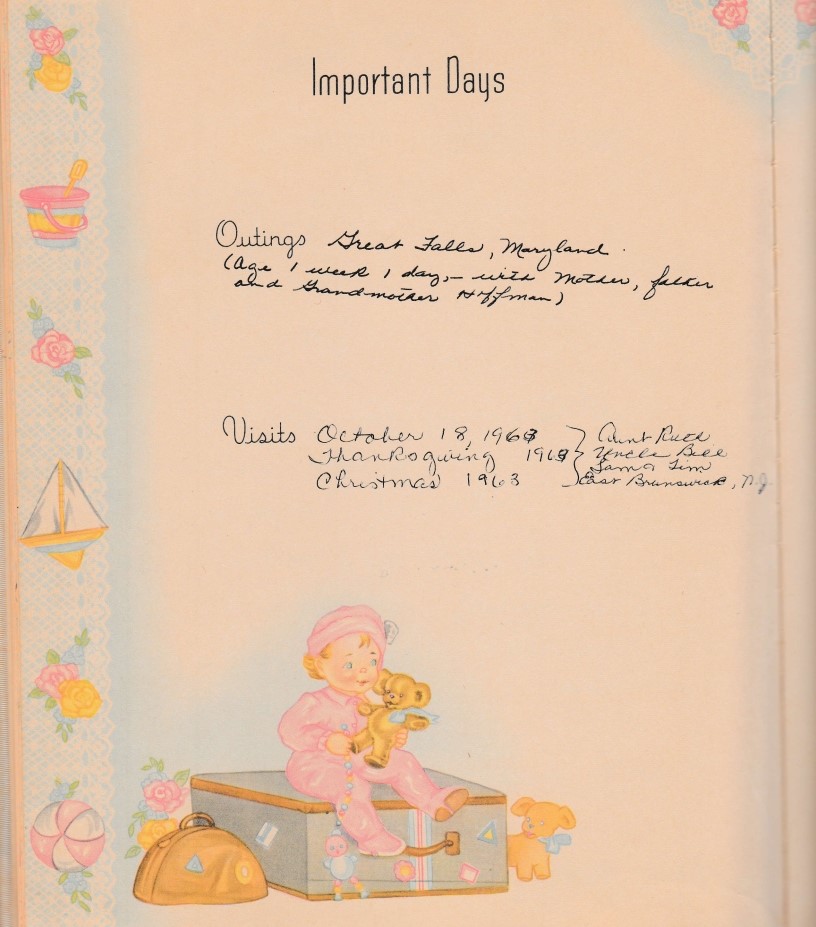

A couple of years ago, in December of 2021 to be exact, when I came across my baby book in a box at my mom’s Assisted Living apartment in Florida, I found out that my first outing at one-week-old was to Great Falls Park in Maryland.

This was an unexpected confirmation for me of a feeling I have had for awhile that I was connected to the information that I am sharing in my work from the very beginning of my life because my whole life I have been collecting pieces to the puzzle long before I was consciously aware of it.

So the Great Falls of the Potomac is the place where I am going to start my journey to provide you with compelling evidence for the connection between gorges, waterfalls, rapids, railroads, bridges, canals and star forts on the Earth’s original grid system.

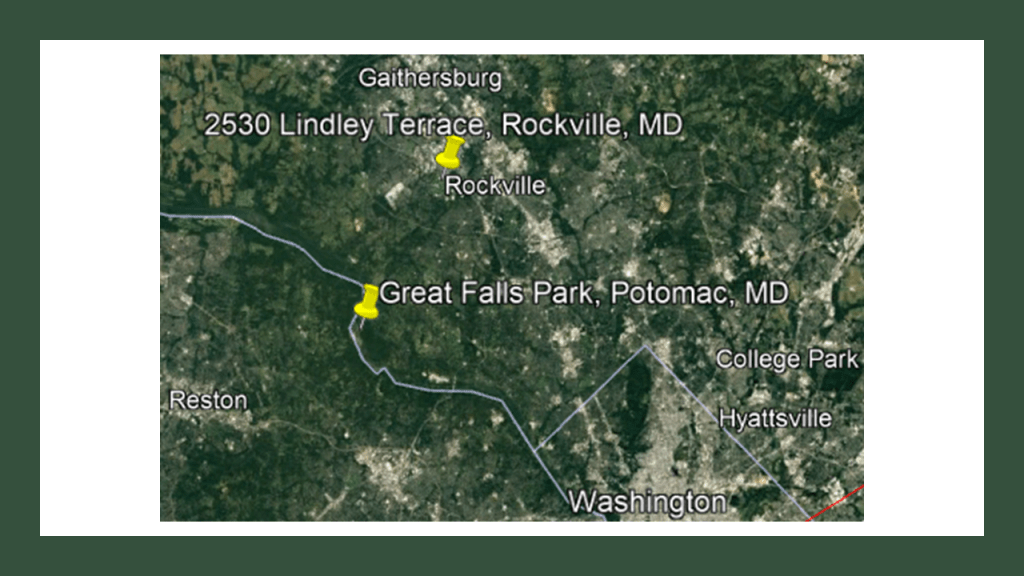

I grew up in Gaithersburg and Rockville in Montgomery County Maryland, outside of Washington, D.C.

In 1974, right after the birth of my youngest brother, when I was ten, we moved to a larger home in Rockville from Gaithersburg. I always tell people we moved as close to the affluent suburb of Potomac, Maryland, as my parents could afford.

This house in Rockville was a short, under 20-mile, or 32-kilometer drive to the Maryland-side of Great Falls Park.

Living so close to the park growing up, I visited there more than a few times.

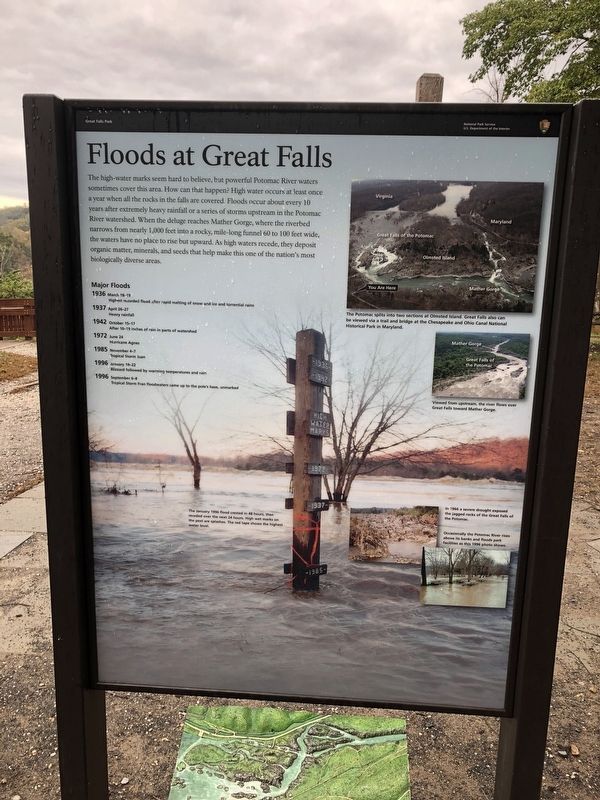

Access to go see the Great Falls themselves, at least when I was young, was cut off after the effects of Hurricane Agnes in 1972 destroyed the bridge going out to where you could view them from the Maryland-side.

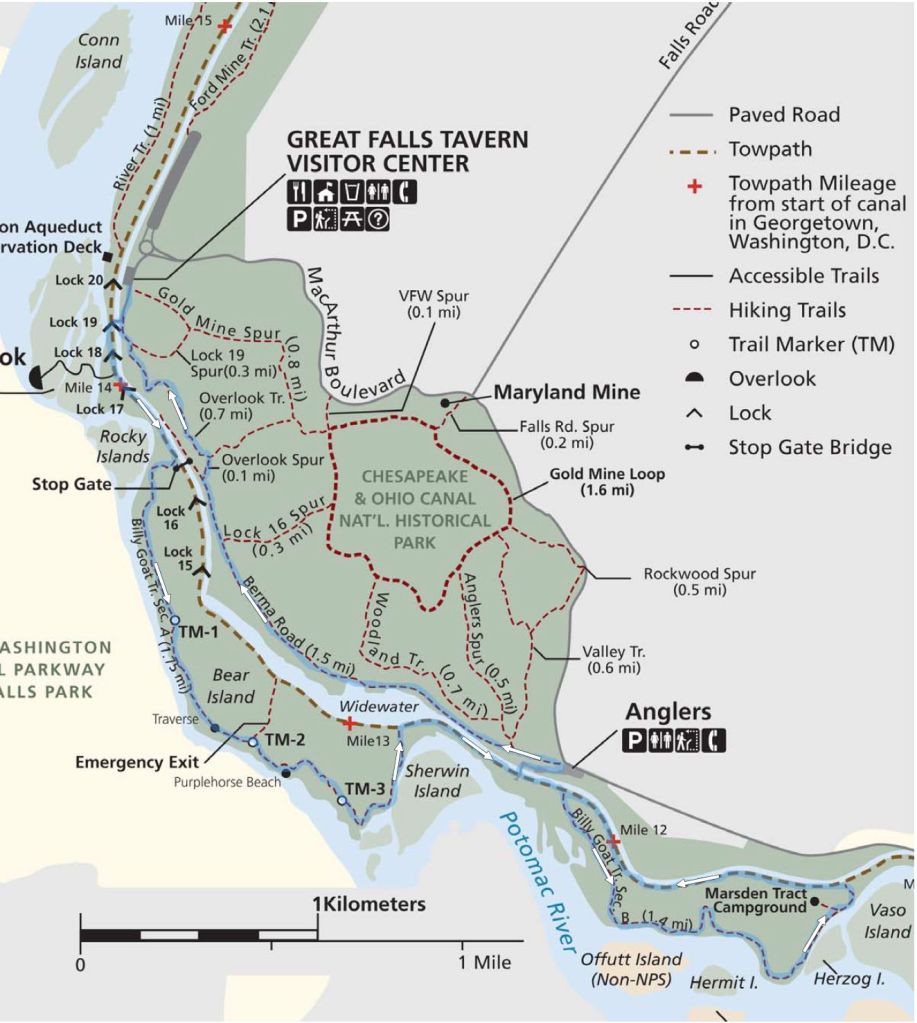

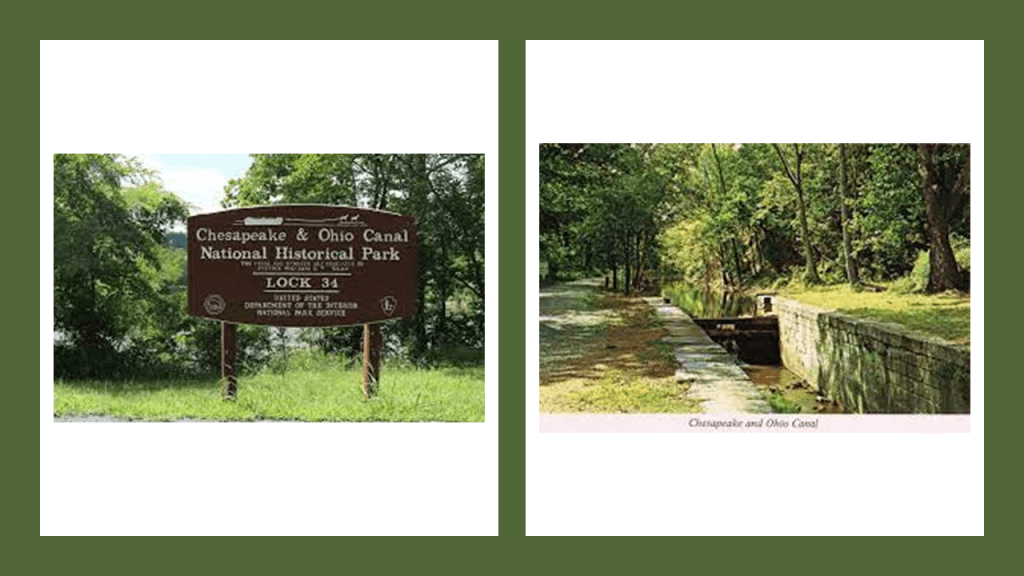

My most vivid memories of Great Falls are of the C & O Canal that runs through the park, complete with canal locks, tavern/museum, and a variety of recreational opportunities to choose from, including hiking trails and canoeing or kayaking on the canal.

And the only time I ever skipped school was Senior Skip Day when I was in high school, and I went with some classmates to Great Falls Park, and I am pretty sure that was the only time I hiked the “Billy Goat Trail” there.

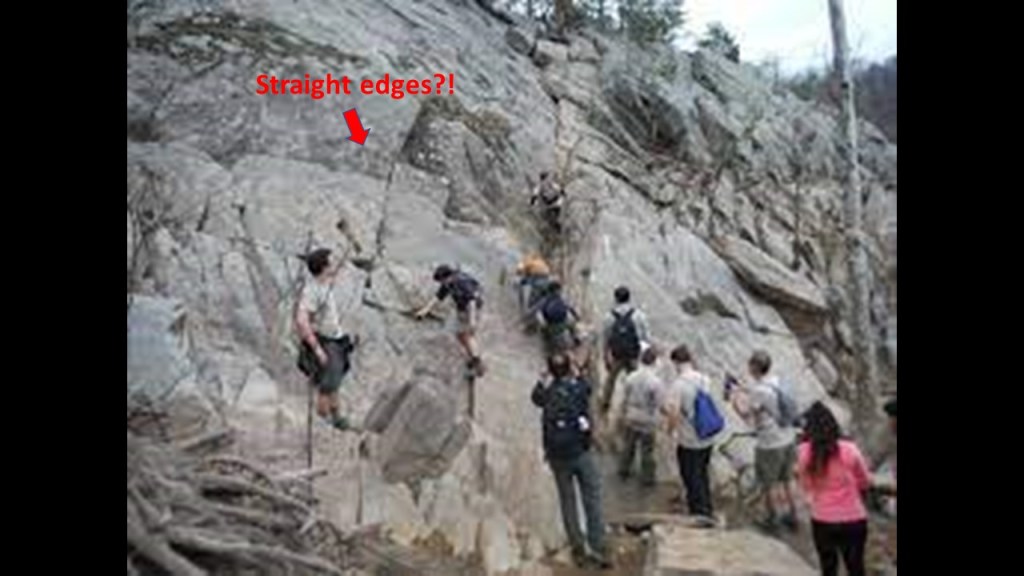

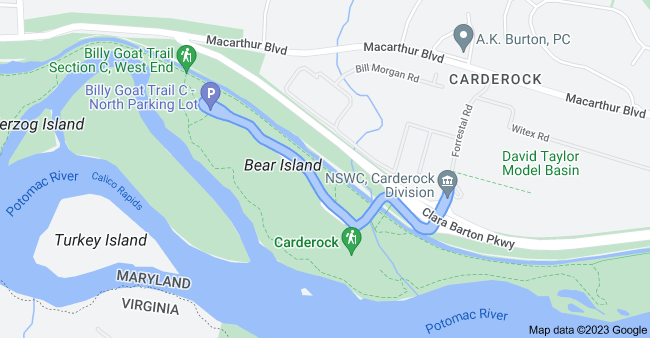

The Billy Goat Trail includes a section along the Mather Gorge, part of the C & O Canal National Historic Park, and named after the National Park Service’s first director, Stephen Mather.

A gorge or canyon are both defined as a deep cleft between escarpments or cliffs resulting from weathering or erosive activity of a river over geologic time scales.

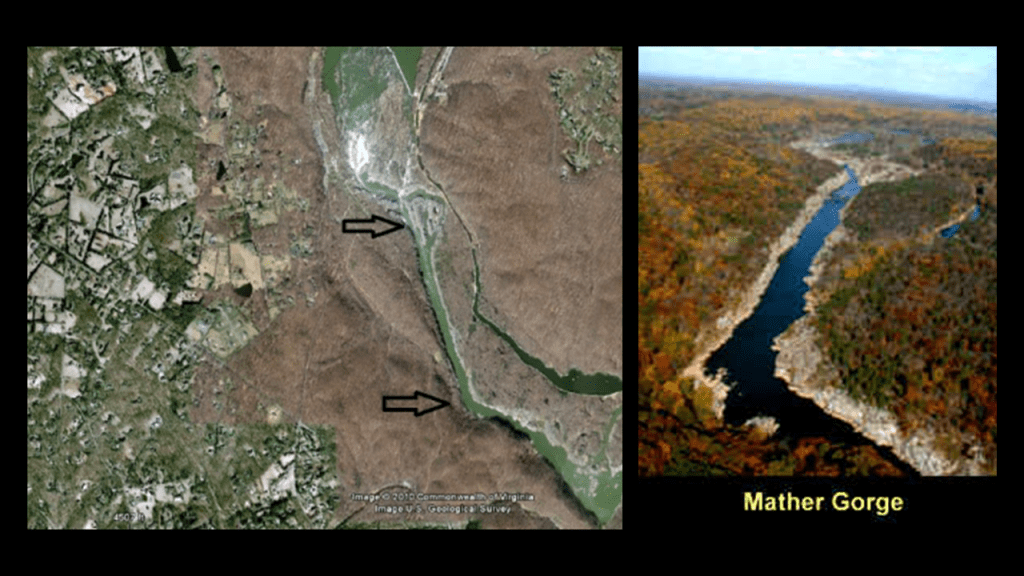

This is an aerial image of Mather Gorge on the left and how it looks closer to earth.

So the spin is that this is completely natural, but the edges of the gorge look to be on the straight-and-angled-side!

The Carderock Recreation Area is part of the C & O Canal National Historic Park.

Carderock itself is a popular rock-climbing location.

Interesting to note that the Carderock Division of the Naval Surface Warfare Center is located in Carderock, Maryland, not far from Carderock rock, and concentrates on engineering, testing, and modelling ship and ship systems for the Navy.

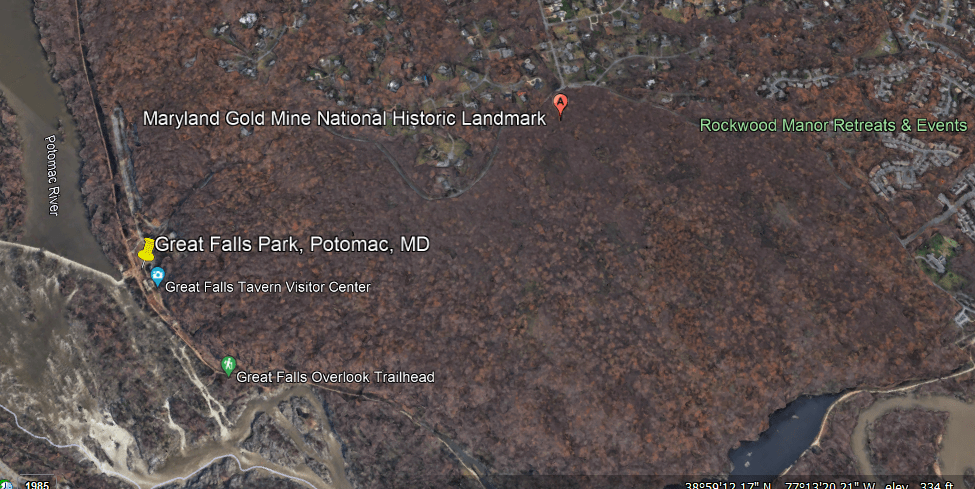

Funny, I don’t remember there being a gold mine here.

Close to Rockwood Manor, too!

I have recently come into awareness of the giant trees that once existed all over the Earth and their likely relationship to the Earth Grid and mine site through the “Deeper Conversations with Chad” YouTube Channel. Chad recently had a conversation with me, and we talked about giant trees among other shared findings coming from different perspectives.

Now I’m wondering if this could this have once been the location of a giant tree?

Now to start bringing in other infrastructure.

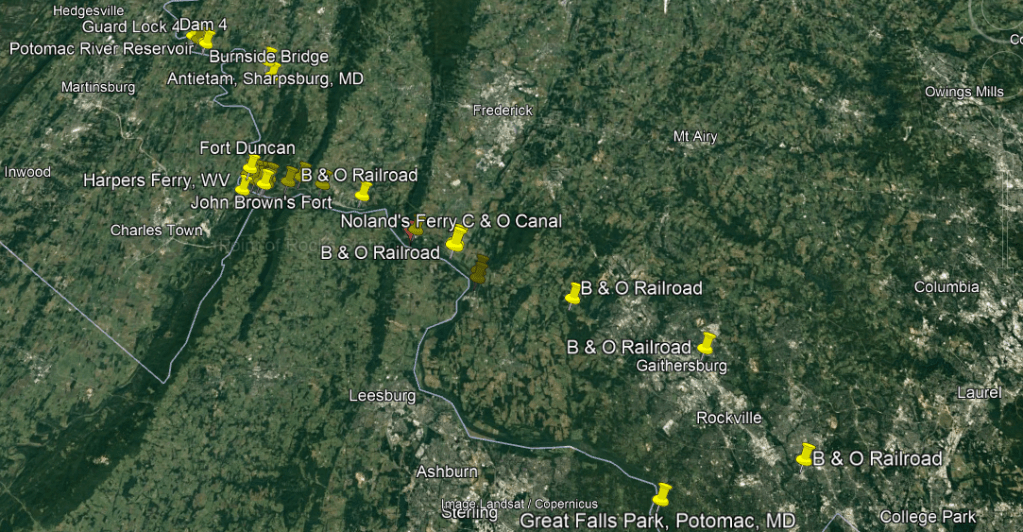

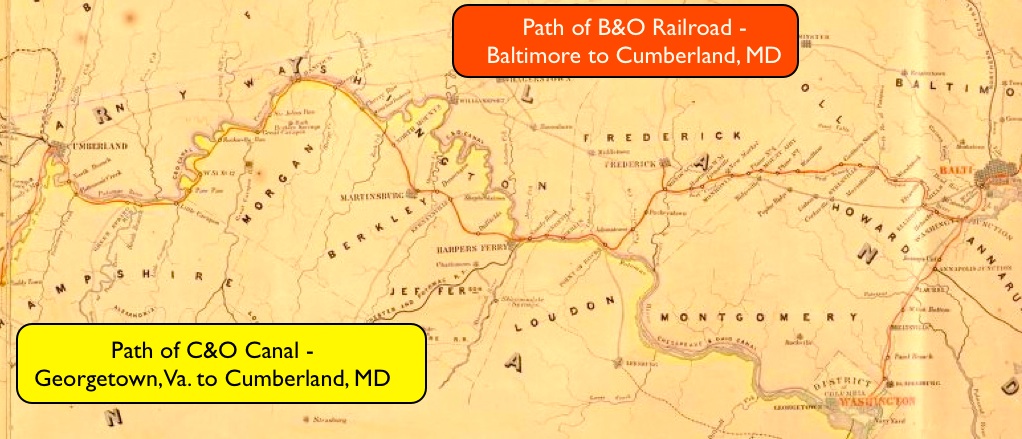

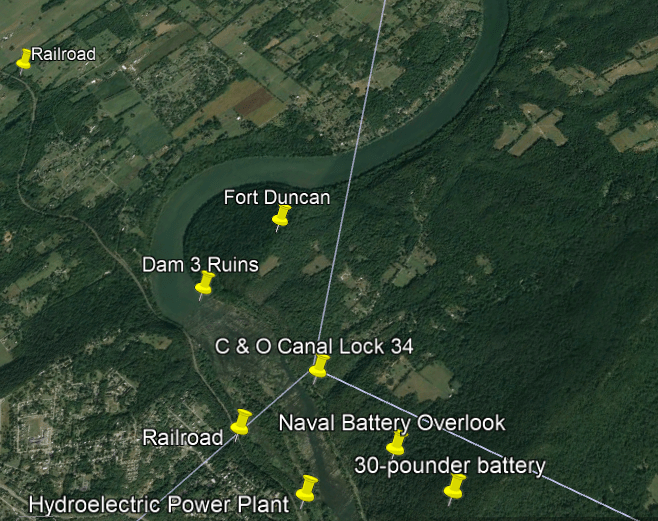

Here is a Google Earth Screenshot along the Potomac River between Great Falls Park in Potomac, Maryland, showing all the infrastructure that is found along here in-between there and the Potomac River Reservoir north going through Harper’s Ferry, including the C & O Canal, the B & O Railroad, bridges, aqueducts, reservoirs, forts and batteries.

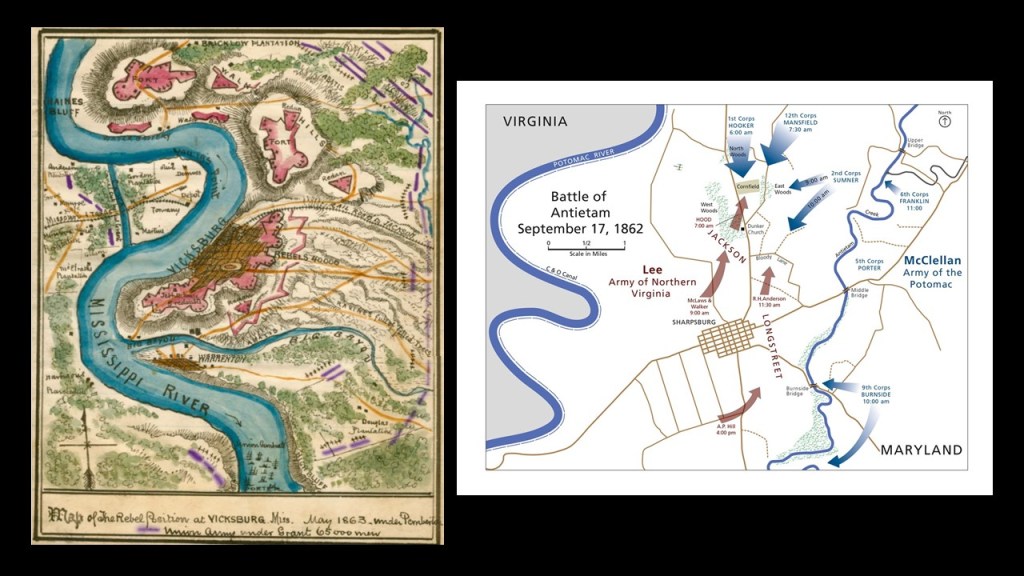

Harper’s Ferry was an infamous location during the American Civil War, and so was the Battle of Antietam in Sharpsburg, Maryland, one of its bloodiest battles.

Again, since I grew up near here, I have been to a number of these places multiple times, particularly Harper’s Ferry and Antietam.

Here’s what our historical narrative tells us.

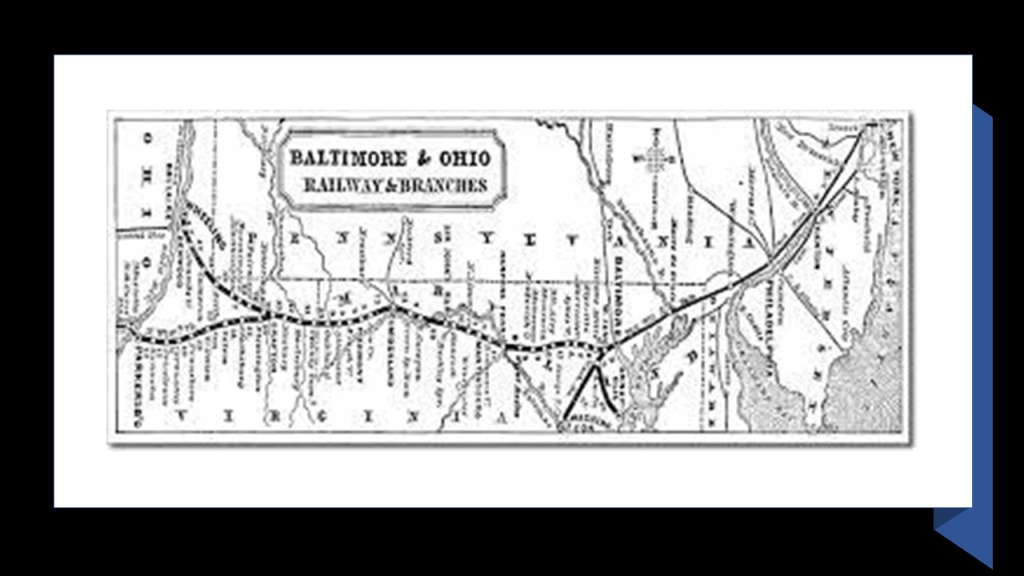

In 1827, the State of Maryland chartered the Baltimore and Ohio (B & O) Railroad, the first common carrier, and the oldest, railroad in the United States.

The first section of the B & O Railroad was said to have opened in 1830, and it was said to have reached the Ohio River in 1852, the first eastern seaboard railroad to do so.

We are told there was an intense rivalry between the B & O Railroad, and the Chesapeake & Ohio (C & O) Canal, with each project choosing the same day to break ground – on July 4th, 1828.

Both projects were said to be vying for the narrow right-of-way where the Potomac River cuts through a mountain ridge not far from Point of Rocks, Maryland, which ended up in court.

Even though after four-years the case was said to have been ruled in favor of the canal, we are told the C & O had to allow the B & O to go through there, so this is a place where the canal and the railroad run side-by-side, and that within a few years the canal was made obsolete because the railroad was so much more efficient.

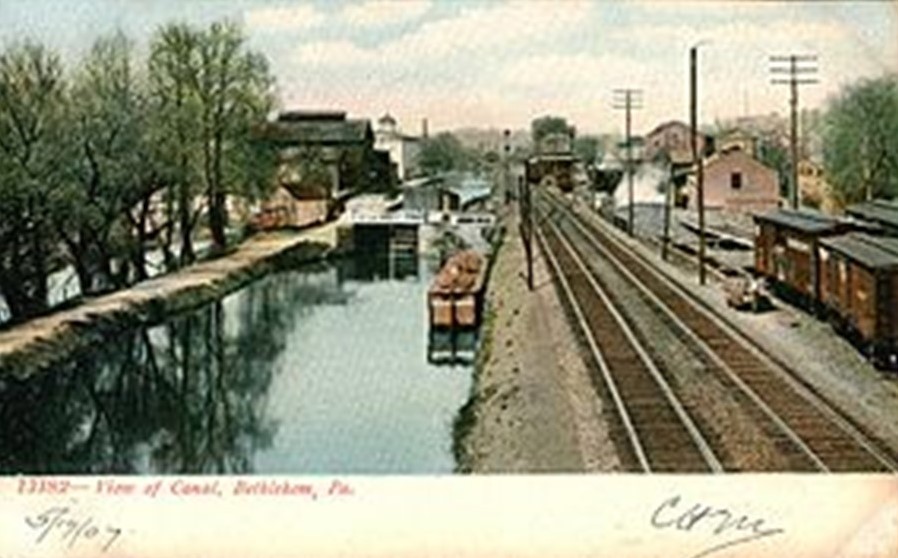

And this incredible engineering feat of canals and railroads running side-by-side is found in countless other places, with examples like this one in Bethlehem, Pennsylvania…

…and this one of the Ship Canal on Michigan’s Keweenaw Peninsula.

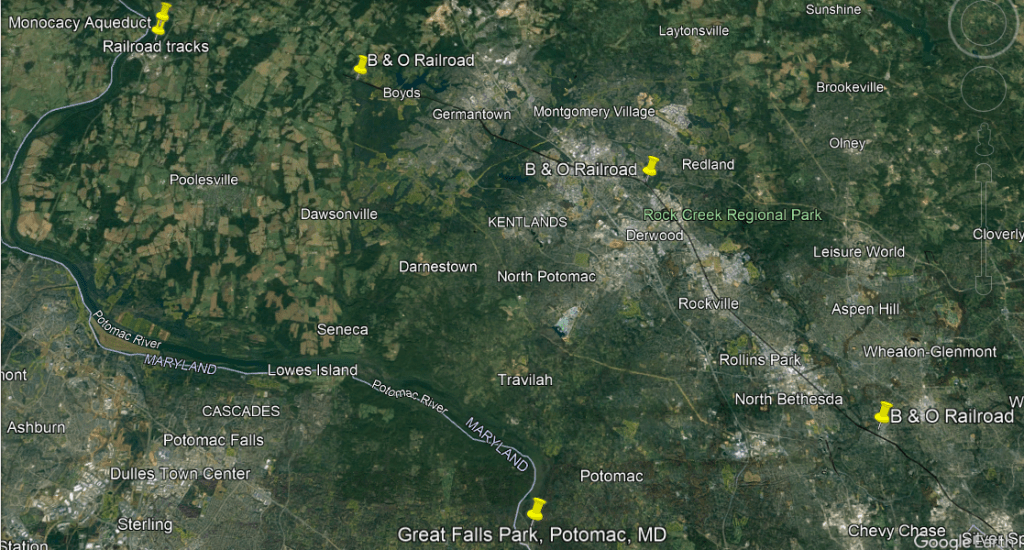

I am going to take a look at the places between Great Falls Park in Maryland and the Potomac River Reservoir in West Virginia section by section on Google Earth.

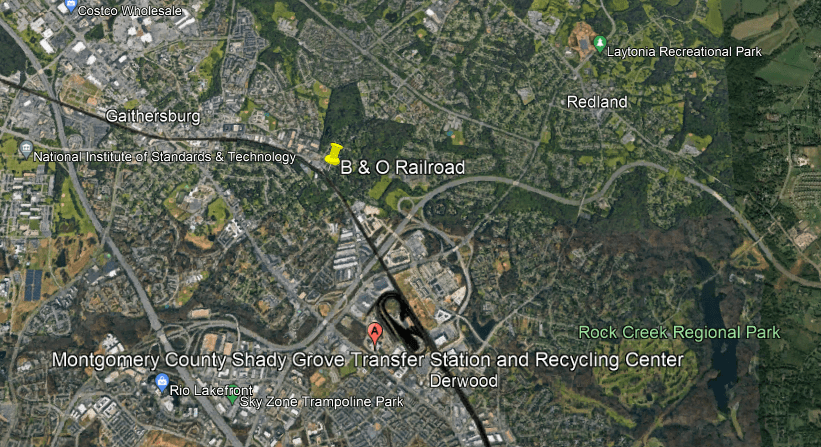

This first section in Montgomery County was totally in my stomping grounds growing up.

The first two pins down at the bottom of the screen show the relationship and distance at the locations between the Potomac River, Great Falls and the C & O canal, and where the B & O Railroad today makes its way through Montgomery county.

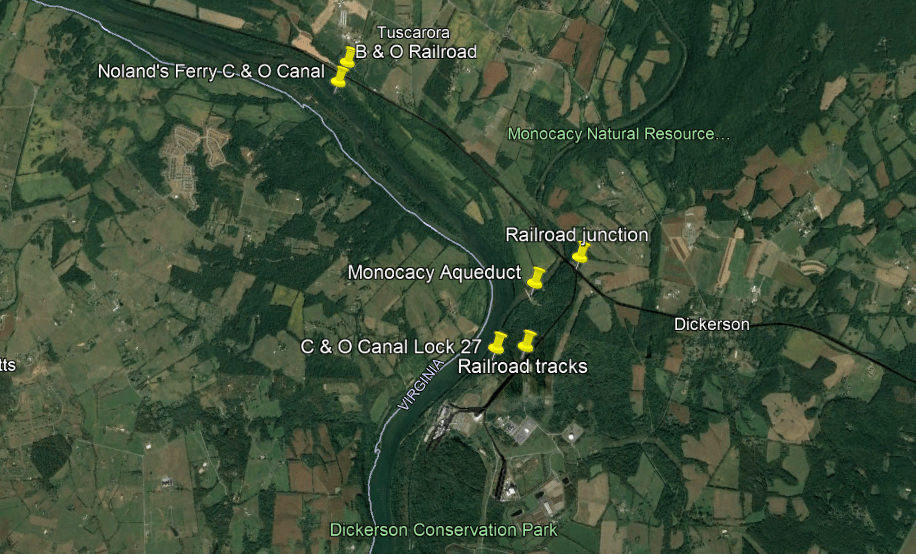

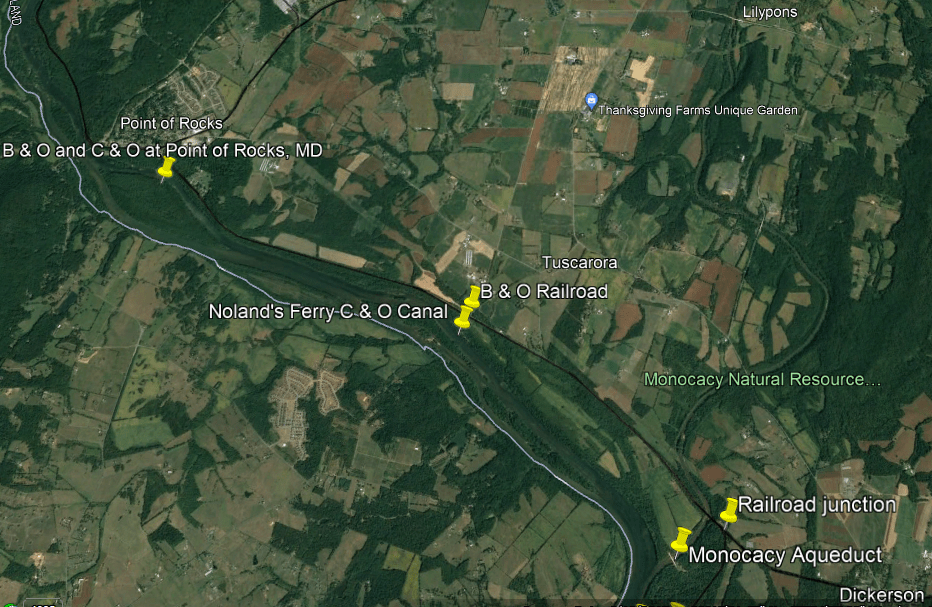

Now I want to bring your attention to what was at the top left of the previous screenshot at the pins of “Monocacy Aqueduct” and “Railroad tracks.”

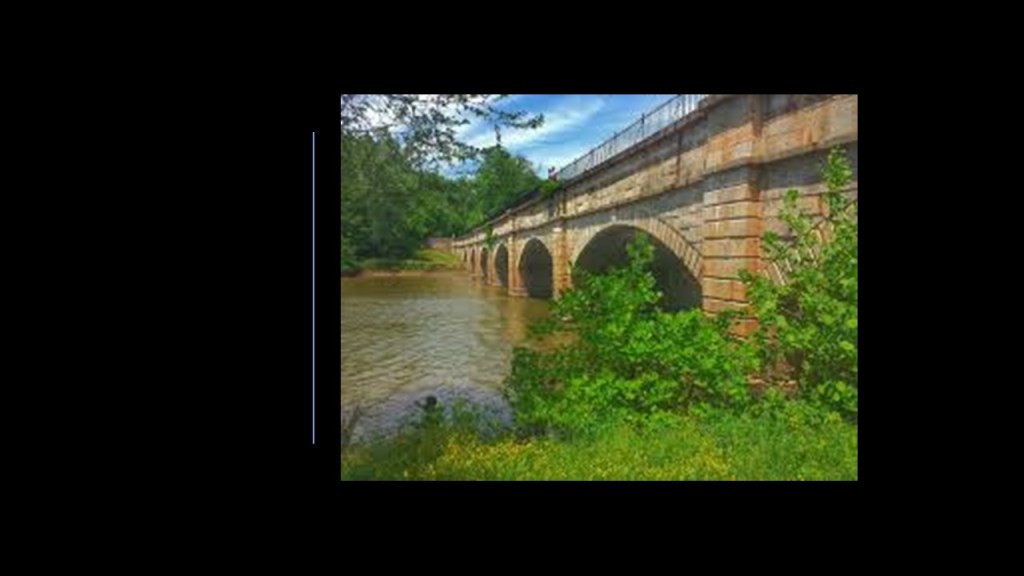

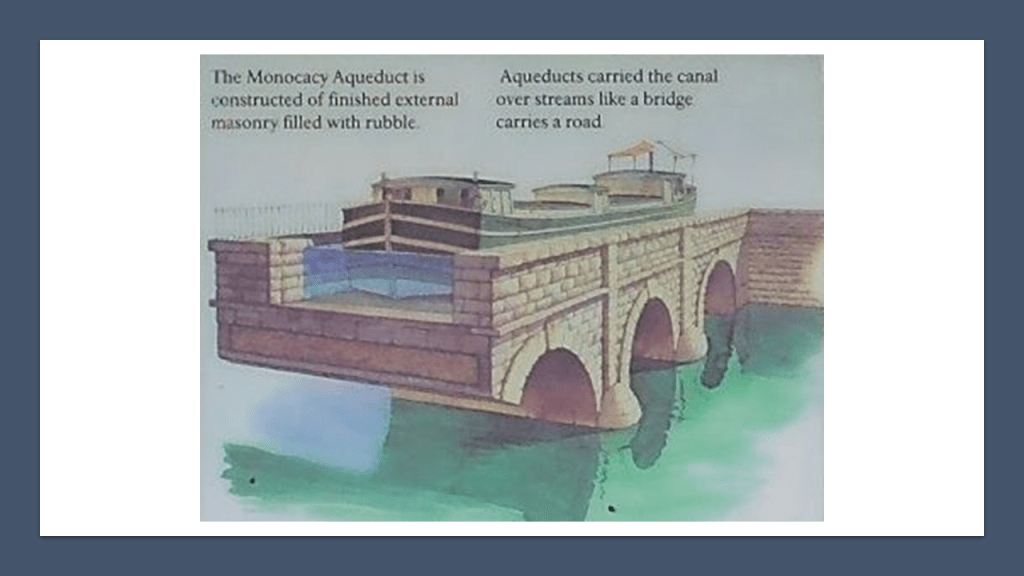

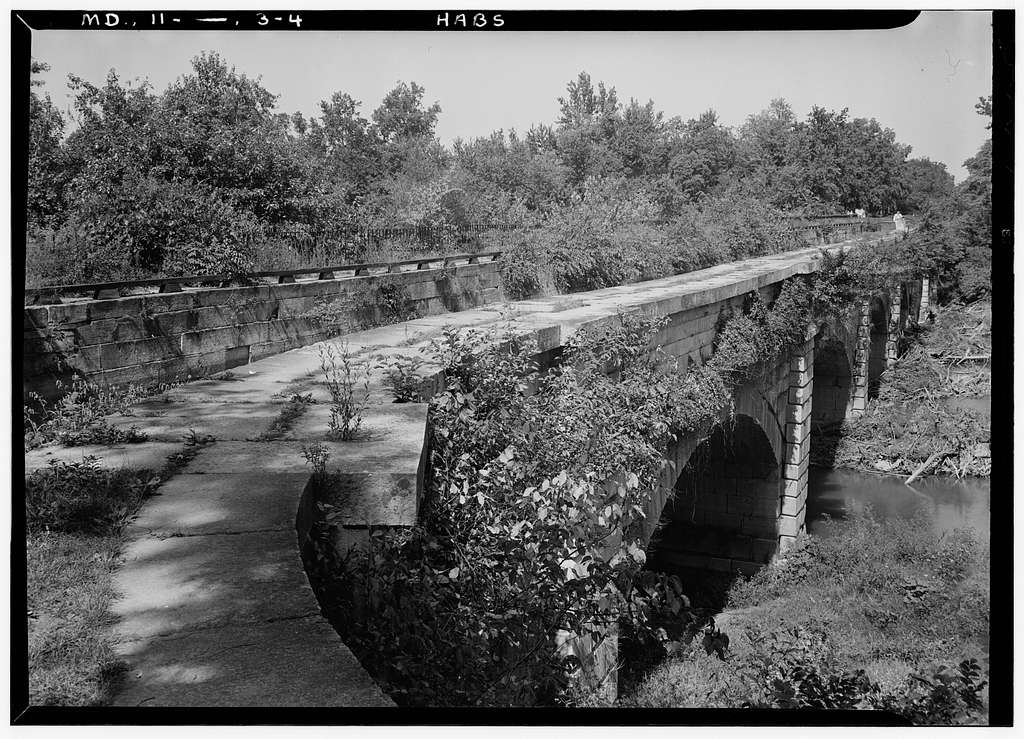

The Monocacy Aqueduct was said to have been built by three different contractors between 1829 and 1833.

It is the longest aqueduct on the C & O Canal, crossing over the Monocacy River before it meets the Potomac River.

This solid, stone-masonry structure has a waterway of 19-feet, or 5.8-meters at the bottom, and 20-feet, or 6.1-meters at the top.

It was used as part of the canal system for canal boat transportation, and said to have been utilized by the Union Army during the Civil War to transport war materials and troops between Maryland, Virginia, and places west.

The story goes that the Confederate Army had plans to blow up the aqueduct but were unsuccessful in doing so for a variety of reasons, from being talked out of it by the keeper of Lock 27, to not being able to drill enough holes to insert the amount of dynamite necessary to blow it up.

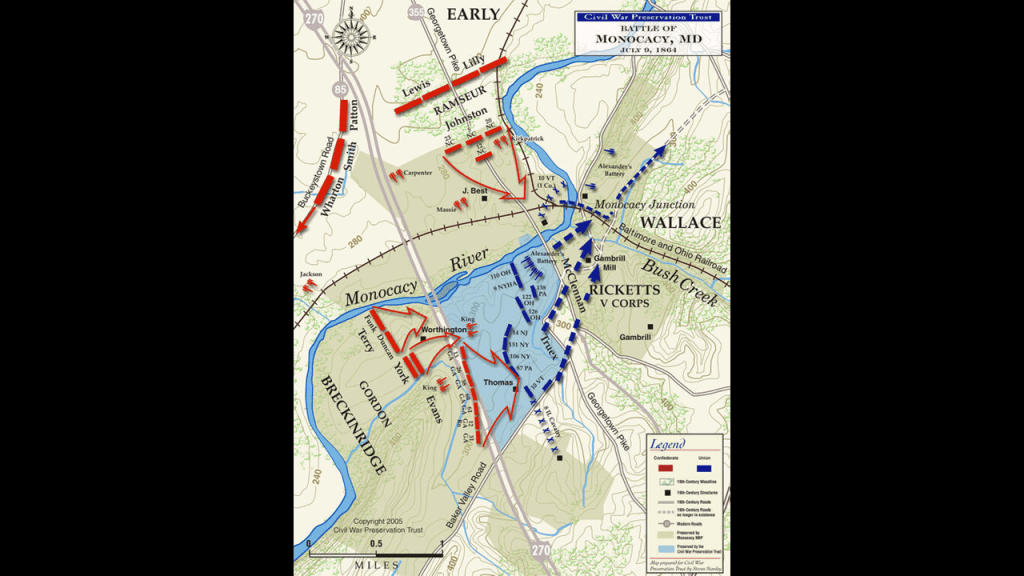

Another is that the Battle of Monocacy took place not far from here in Frederick County in July of 1864, and came about because Union troops were there to protect a railroad bridge at Monocacy Junction, Maryland, where it crossed the Monocacy River, as Confederate troops marched towards Washington.

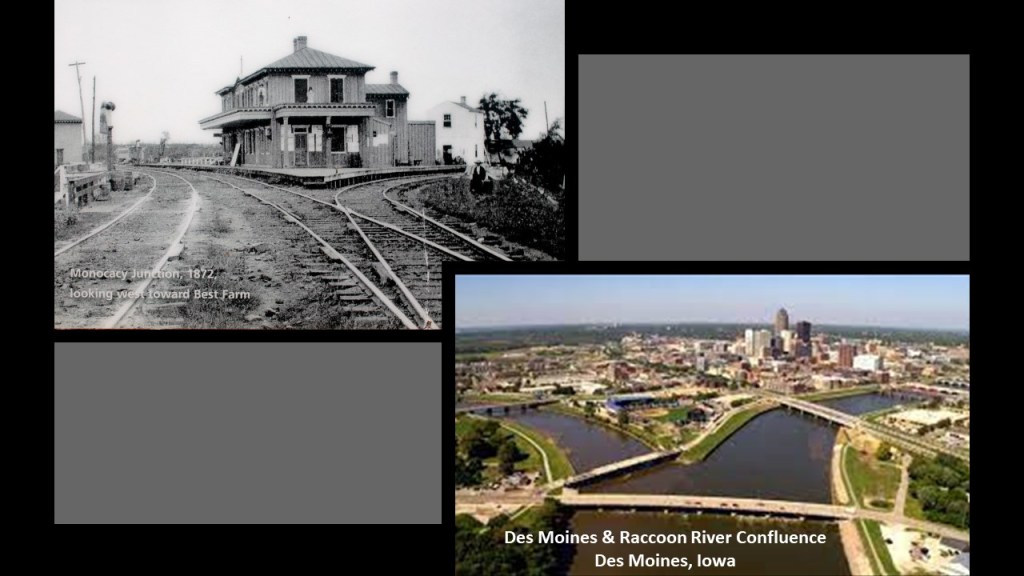

On the top left is a photo of the Monocacy Railroad Junction circa 1873, and on the bottom right is a photo of the confluence of the Des Moines and Raccoon Rivers in Des Moines, Iowa, one of countless examples of so-called river confluences that look exactly like the Monocacy Junction, and were actually canals.

A junction is defined as a “an act of joining or adjoining things,” implying intentionality as opposed to something that just happens randomly.

An electrical junction is defined as a point or area where multiple conductors or semi-conductors make physical contact.

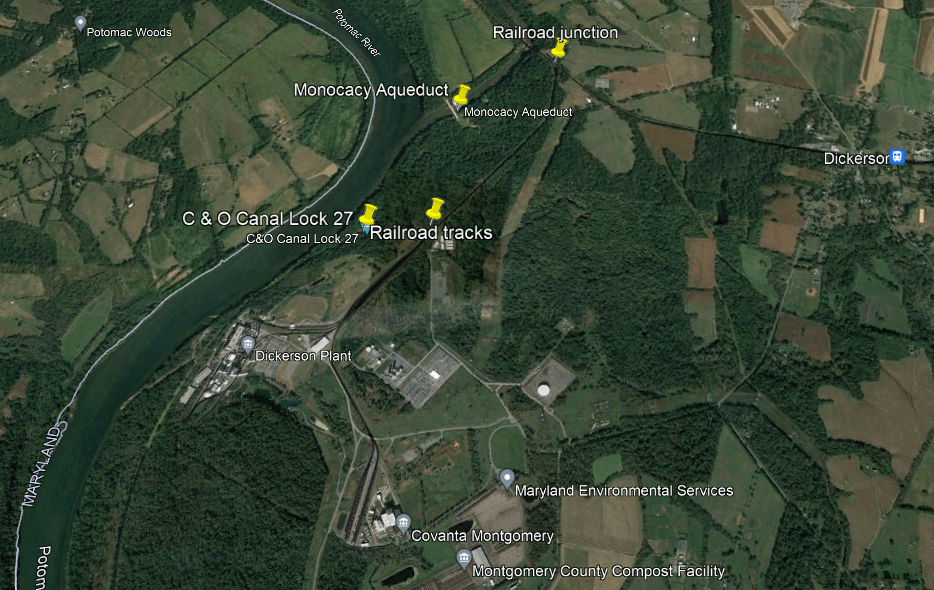

The next point of information here that is noteworthy is that there is another railroad junction near the Monocacy Aqueduct itself, where there is another rail-line branches off from the main B & O rail-line that runs closer to the Potomac River and C & O Canal here.

Also here the C & O Canal is hard to distinguish from the Potomac River through here.

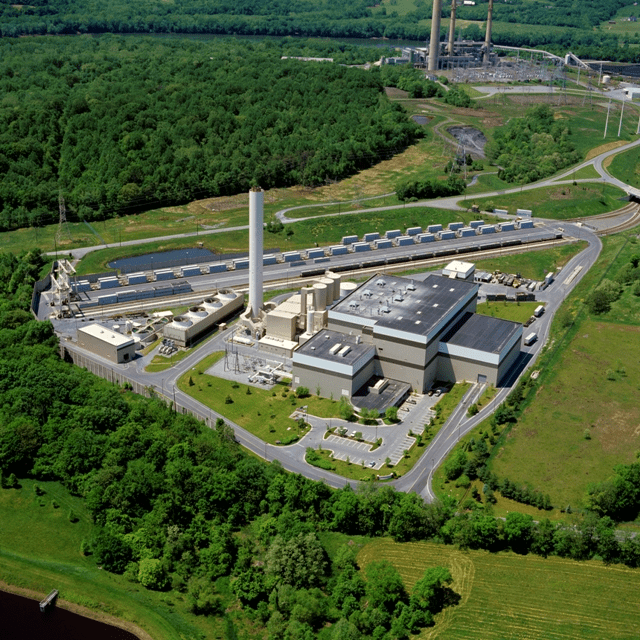

The short Dickerson spur-line runs ends at the facilities for the Dickerson Plant and Covanta Montgomery.

The Dickerson Plant refers to the Dickerson Generating Station, an 853-megawatt electric-generating plant owned by NRG Energy.

It has a history of toxic metal releases into the Potomac River, like arsenic and mercury.

It is located next to the C & O National Historical Park, with C& O Canal Lock 27 being nearby.

Canal Locks are used to raise and lower boats between stretches of water of different levels.

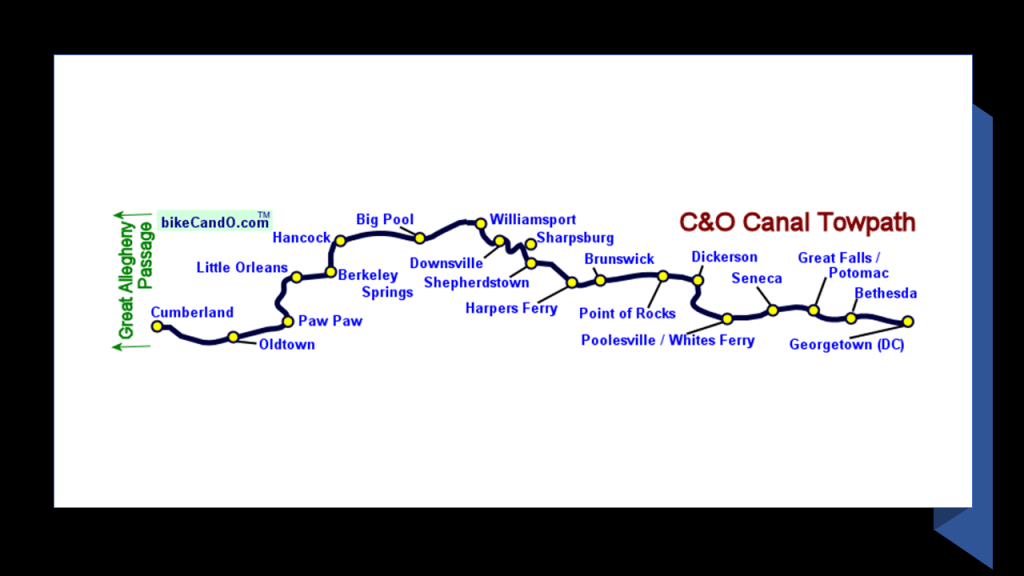

The C & O Canal has 74 locks altogether along its 184.5-mile, or 297-kilometer, length.

Covanta Montgomery is the Montgomery County Resource Recovery Facility, which is a 56-megawatt incineration plant that burns municipal garbage and waste and turns it into energy.

It is served by the CSX railroad line, which brings trash from Montgomery County Central Transfer and Recycling facility in Derwood, Maryland.

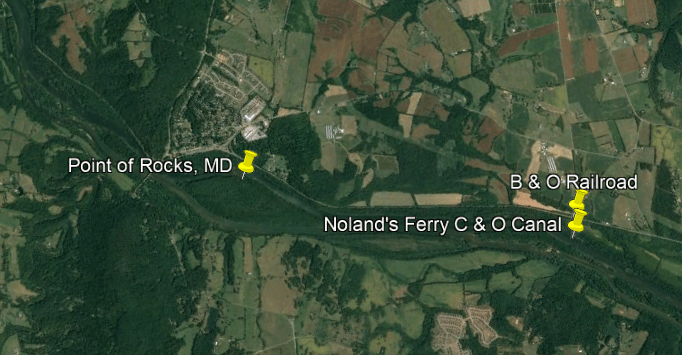

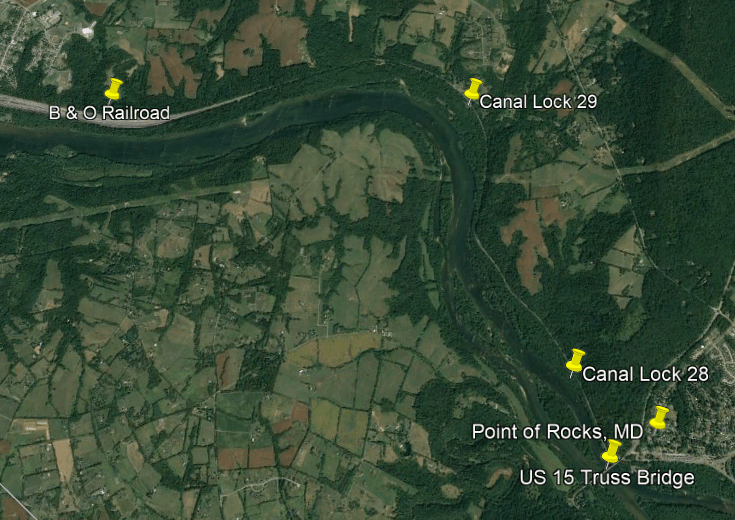

In the next section, from the Monocacy Aqueduct to the train station at Point of Rocks, Maryland, the railroad tracks start to run closer to the the C & O Canal and the Potomac River, and then run side-by-side.

Starting at Noland’s Ferry , the railroad, C & O Canal, and the Potomac River start to run together right next to each other for a long-distance.

Noland’s Ferry started running in the middle of the 1700s, carrying travellers between Loudon County, Virginia, and Frederick County, Maryland.

It was said to have been used for crossing the Potomac River in both the Revolutionary War and Civil War.

This is a stone structure at the entrance to Noland’s Ferry Park…

…and Culvert 71 is located in the park at mile marker 44.04 just before you get to the historical location of Noland’s Ferry at mile marker 44.6.

Both appear to be very old….

Next we come to Point-of-Rocks, Maryland.

So, let’s take a closer look at Point of Rocks.

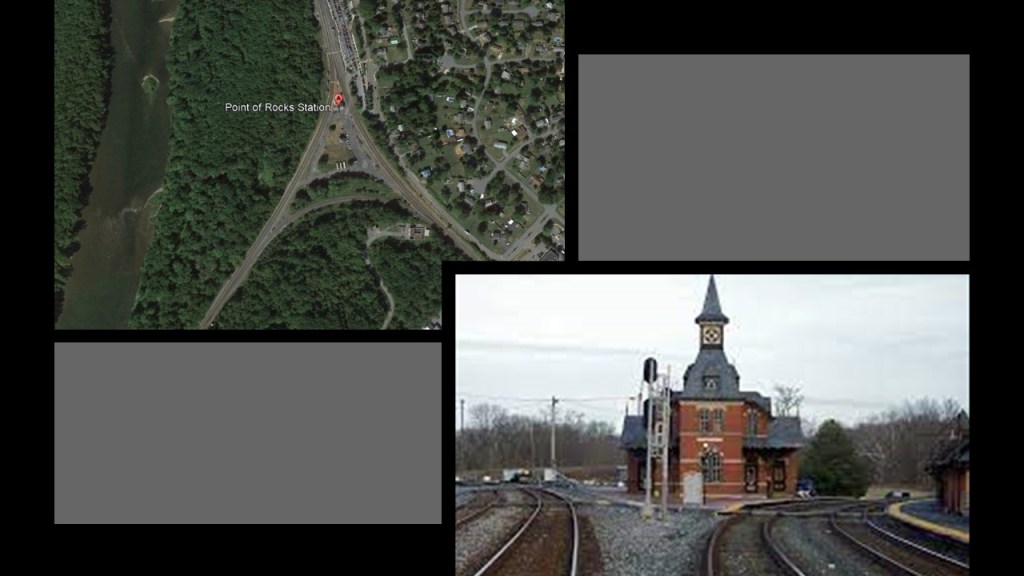

We are told Point of Rocks was the western terminus of the B & O Railroad from 1828 to 1832, while the B & O and C & O awaited the court decision on the hotly-contested right-of-way through here mentioned previously.

The train station here was said to have been built in Gothic Revival-style in 1873 by the B & O Railroad at the junction of the B & O Main-line running to Baltimore and the Metropolitan Branch running to Washington, DC, which had opened for passenger service in 1873.

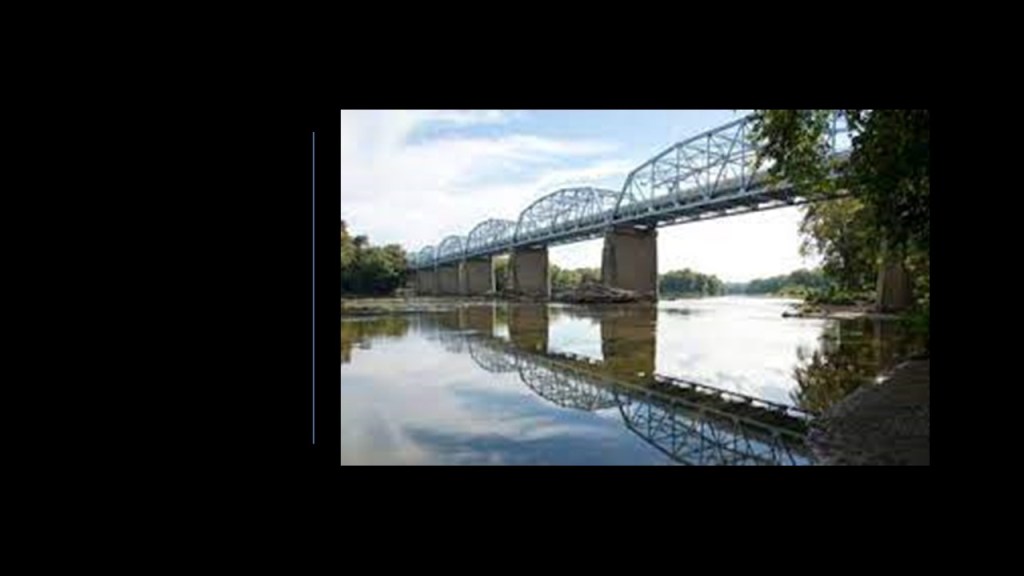

The parking area for the C & O Canal National Historic Park is just south of the U. S. Highway 15 Truss Bridge at Point of Rocks next to the Potomac River.

The two-lane, eight-span Camelback Truss Bridge at this location connects Maryland and Virginia, and was said to have been built in 1937.

U. S. Highway 15 is a United States Numbered Highway that serves New York, Pennsylvania, Maryland, Virginia, North Carolina and South Carolina, and is one of the original numbered highways that was approved in 1926.

It is 792-miles, or 1,274-kilometers, in length.

More on the U. S. Numbered Highway system later in this post.

There are two locks on the C & O Canal near Point of Rocks.

Lock 28 is pictured here…

…and Lock 29 and the Lander Lockhouse are pictured here…

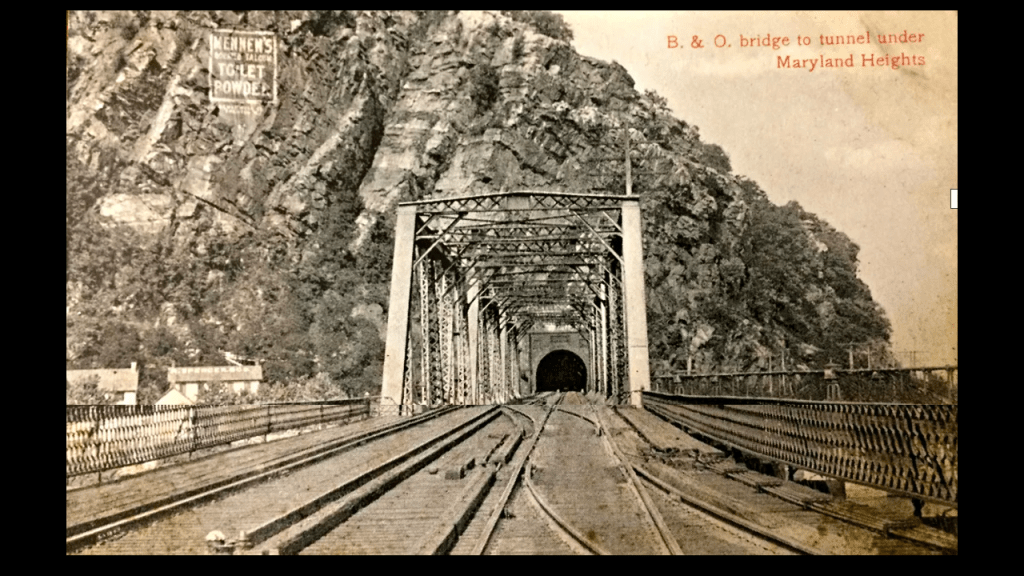

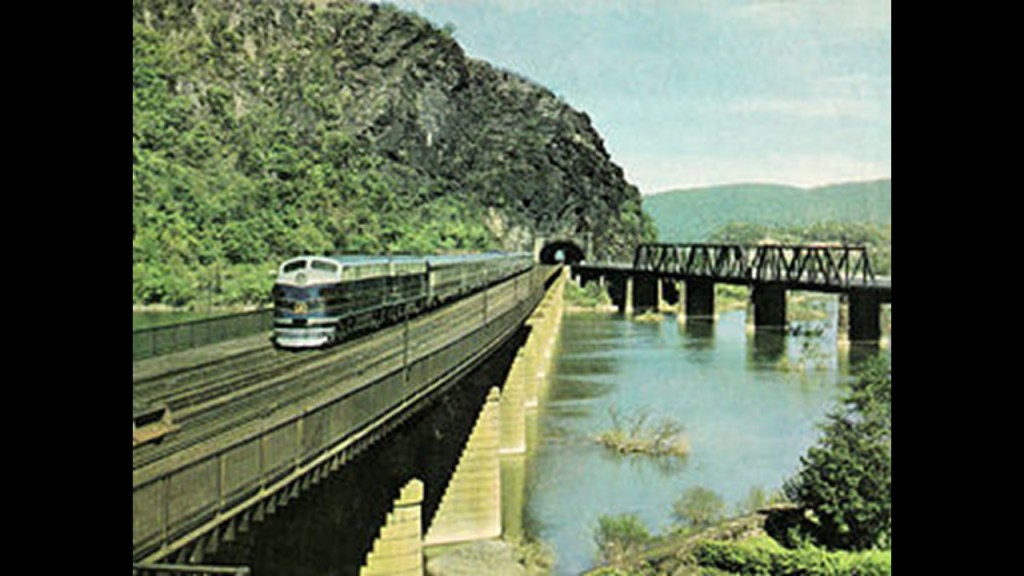

On the railroad’s way to Harper’s Ferry, West Virginia, its tracks run through a tunnel at Maryland Heights

Where the tunnel comes out on the other side, among other things, there is an advertisement for passengers for “Mennen’s Borated Talcum Toilet Powder” high up on the face of Maryland Heights said to date from early 1900s.

The Maryland Heights trail connects to the Appalachian Trail, and I remember being at this location of the tunnel as part of a group hike on the Appalachian Trail through this area when I was a teenager.

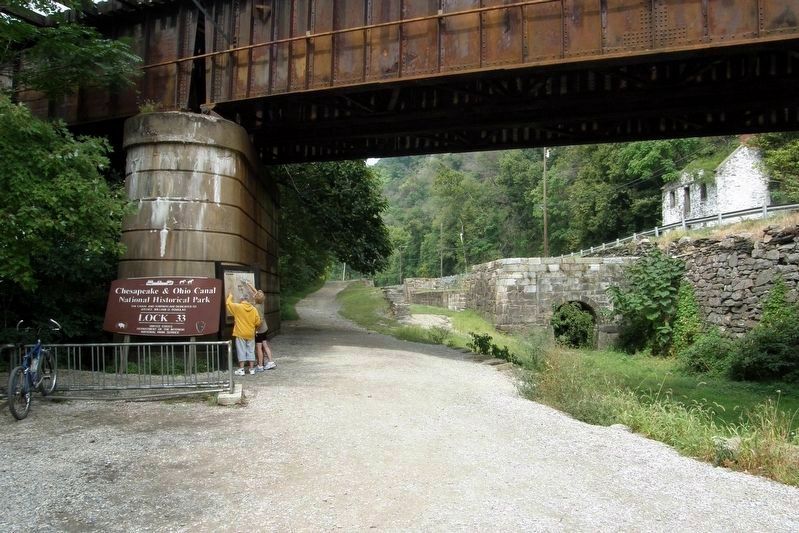

C & O Canal Lock 33 is part of the Maryland Heights Trail.

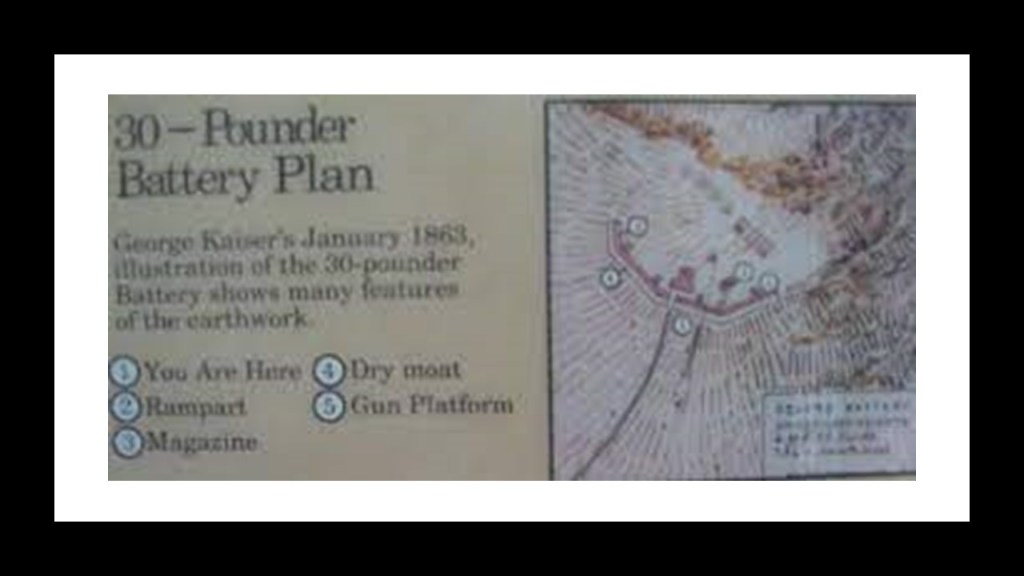

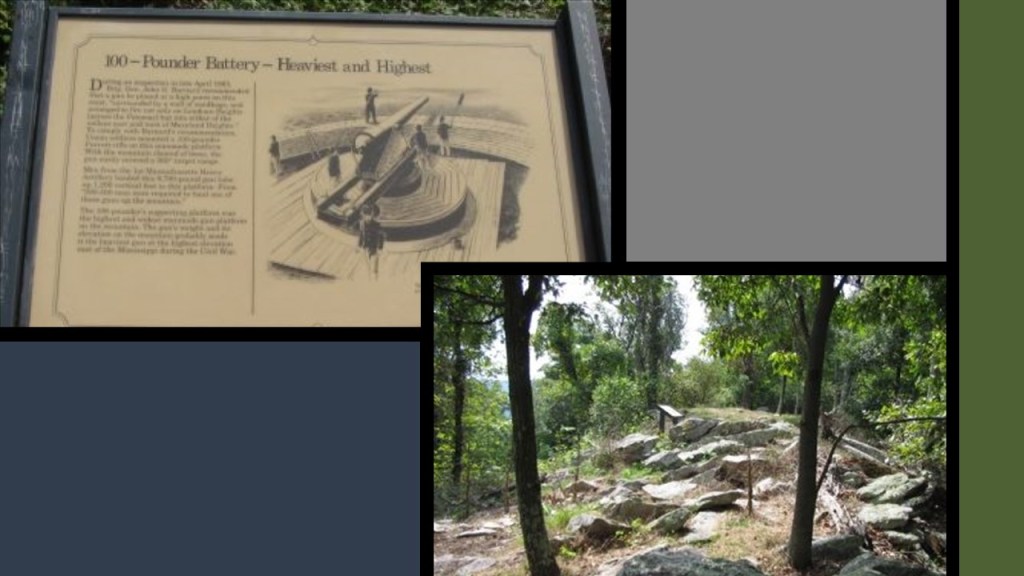

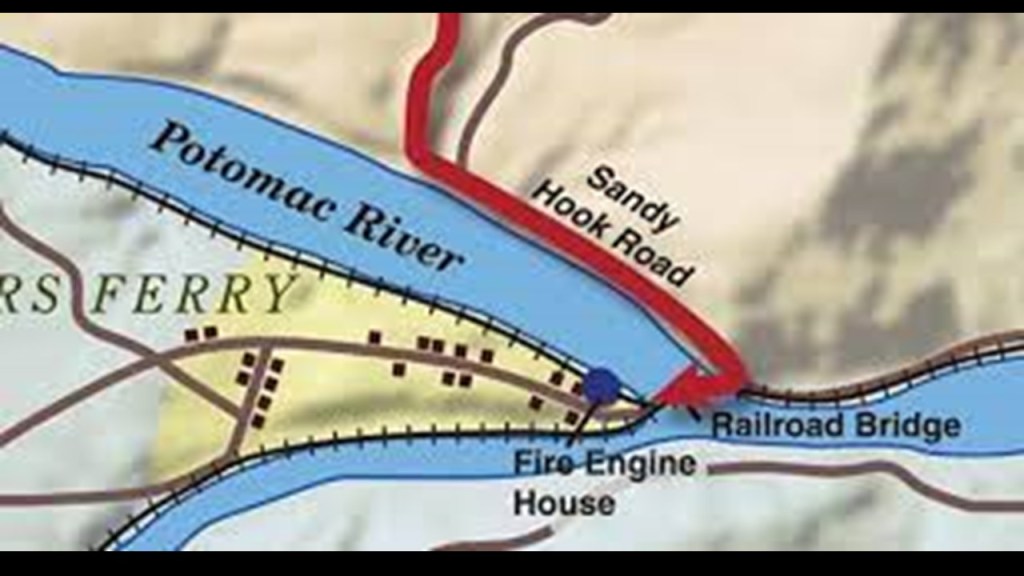

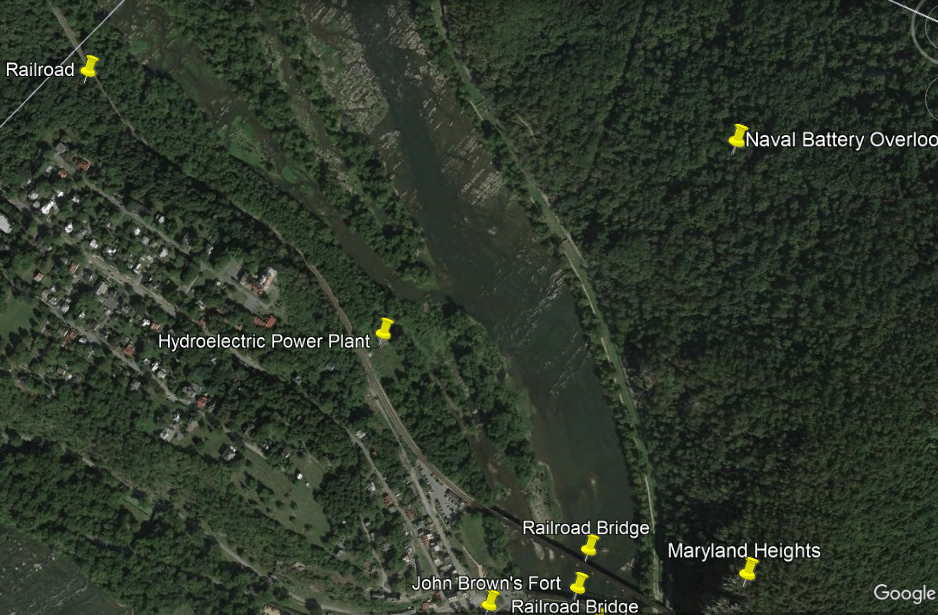

Before crossing over the Railroad bridge here over the Potomac River where the Potomac and Shenandoah Rivers meet, there’s a few places I want to take a look at on this side of the Potomac River here first on Maryland Heights – a 30-pounder battery; a 100-pounder battery; and the Naval Battery Overlook.

On the Stone Fort Loop Trail of the Maryland Heights Trail, the 30-pounder battery was said to have been the first earthen battery built by the federals in the fall of 1862, at the end of a towering plateau that perfectly commanded the summits of Bolivar and Loudoun Heights facing south.

Higher up on Maryland Heights, we come to the 100-pounder battery on the Stone Fort Loop section of the trail.

We are told this battery was recommended by a Union general in the spring of 1863 that could fire a 100-point Parrott rifle 360-degrees in all directions from its lofty location.

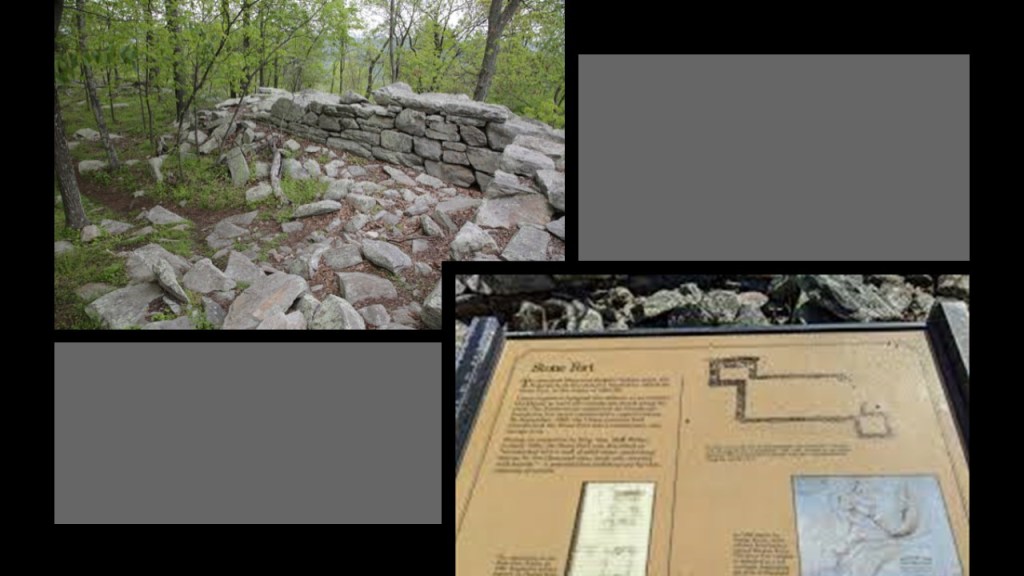

The Stone Fort was said to have been built by the Union Army on top of Maryland Heights during the winter of 1862 and 1863 to ward off Confederate attack along the crest.

The Naval Battery was said to have been the first Union Fortification on Maryland Heights, and quickly built in May of 1862 to protect Harper’s Ferry from Confederate attack during General Stonewall Jackson’s Shenandoah Valley Campaign in the spring of 1862, and where there was a battle with Jackson’s troops in September of 1862.

The Union forces were said to have been forced to retreat and abandon the Naval Battery until they came back to Maryland Heights to build the better fortications we just saw higher up.

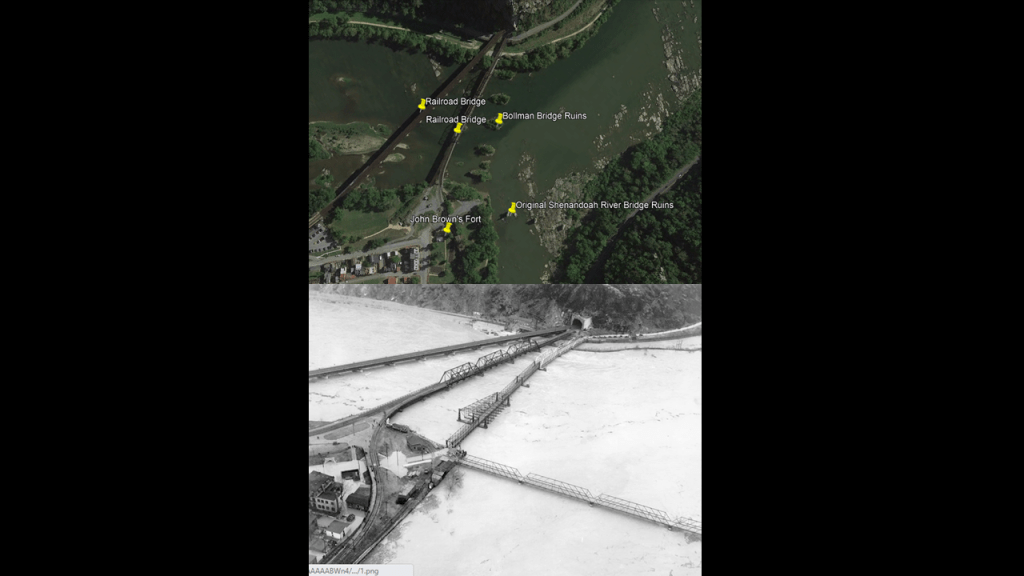

There’s a set of railroad bridges crossing the Potomac River at the confluence of the Potomac and Shenandoah for two different lines.

One continues along the Potomac River and the other is a line that runs next to the Shenandoah River.

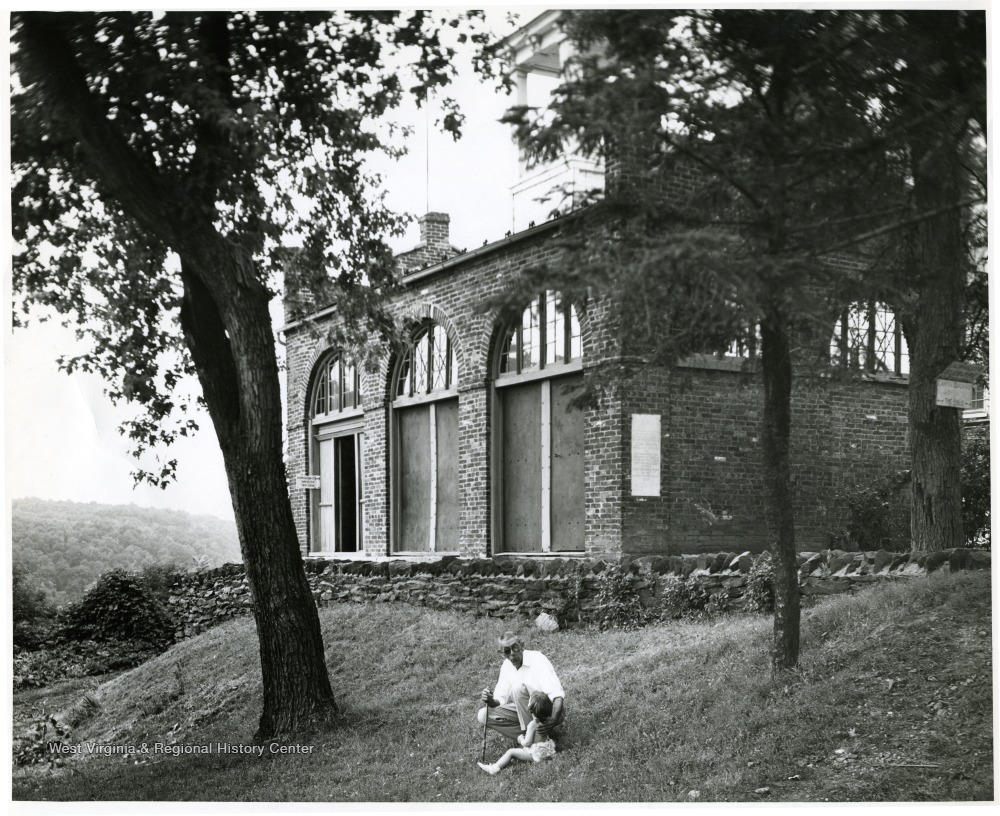

What is known as “John Brown’s Fort” sits at the confluence of the two rivers.

It was said to have been built in 1848 as a guard and fire engine house for the Federal Armory at Harper’s Ferry.

Master Mason John Brown was best known for the Harper’s Ferry raid on October 16th of 1859.

His plan was to raid the Federal Armory and instigate a major slave rebellion in the South, and he had no rations or escape route.

In 36-hours, troops under the command of then Lt. Col. Robert E. Lee had arrested him and his cohorts, who had withdrawn to the engine house after they had been surrounded by local citizens and militia.

While his plan was doomed from the start, John Brown’s Raid did serve to deepen the divide between the North and South in the years leading up to the Civil War.

John Brown was hung on December 2nd of 1859, less than two months after the onset of the Harper’s Ferry Raid.

Interestingly, we are told that many of the bricks of “John Brown’s Fort” were taken and sold as souvenirs…

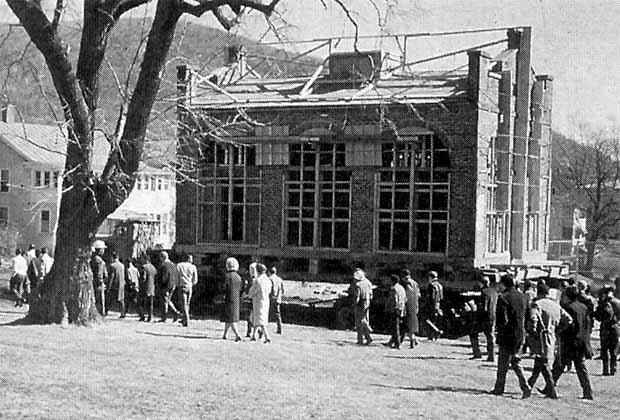

…and that “John Brown’s Fort” was said to have been moved four times.

To Chicago, for an attraction at the 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition; back to Harpers Ferry on the Murphy Farm in 1895; Storers College in Harpers Ferry in 1909; and back to its present, and close to its original location, by the National Park Service in 1968.

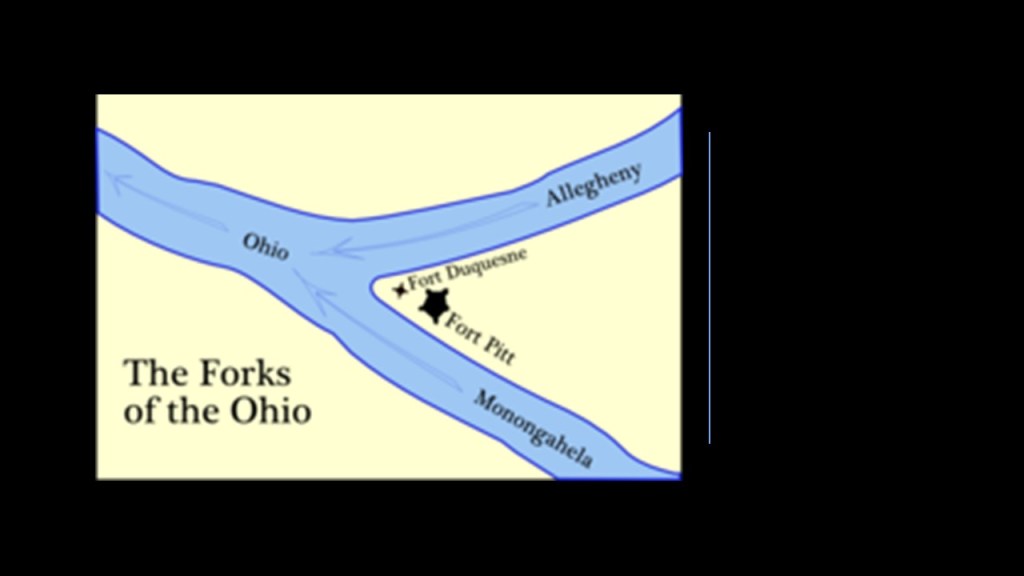

What I find interesting about finding “John Brown’s Fort” at this location is that I typically find either still-existing or historic star forts at the point of river confluences like here in Harper’s Ferry.

Examples include Fort Pitt and Fort Duquesne at the “Forks of the Ohio” in Pittsburgh…

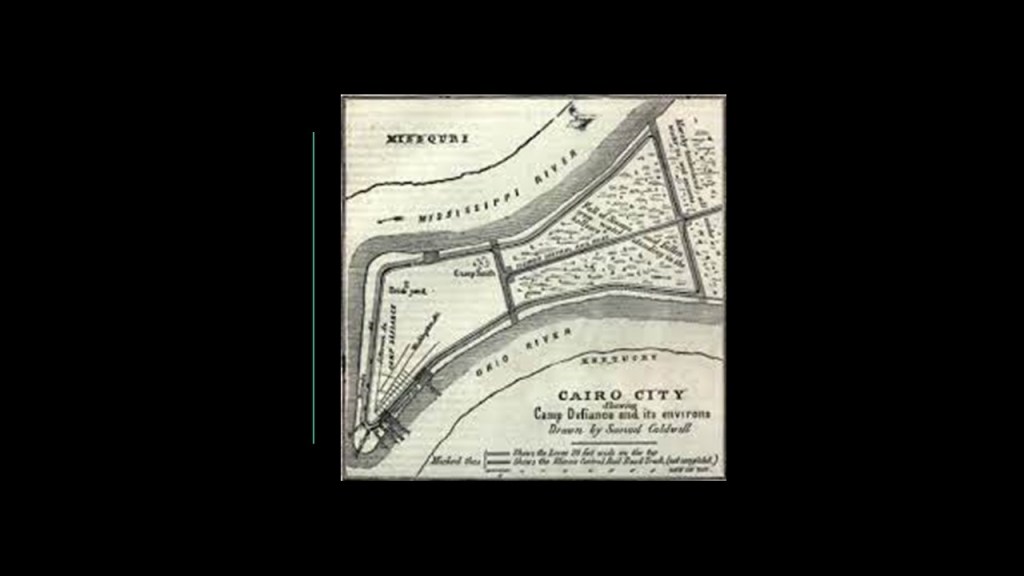

…and the historic first Camp, and later Fort, Defiance at the confluence of the Mississippi and Ohio Rivers in Cairo, Illinois.

Before I follow the C & O Canal and B & O Railroad along the Potomac River, I just want to take a quick look at some places on the Shenandoah River-side.

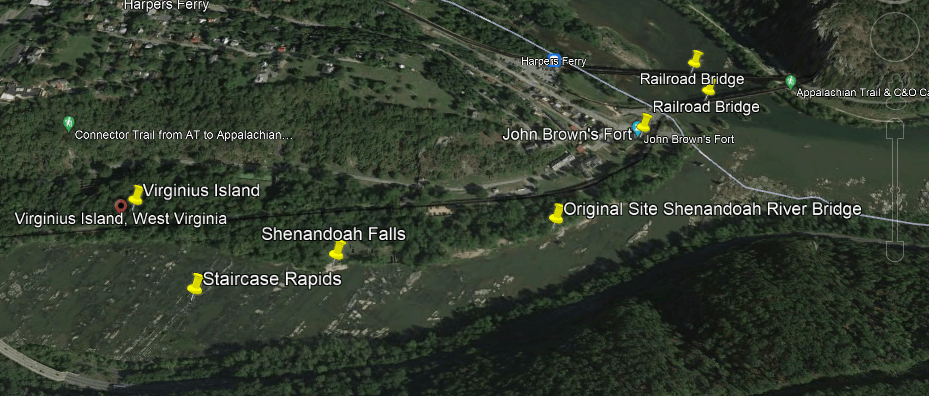

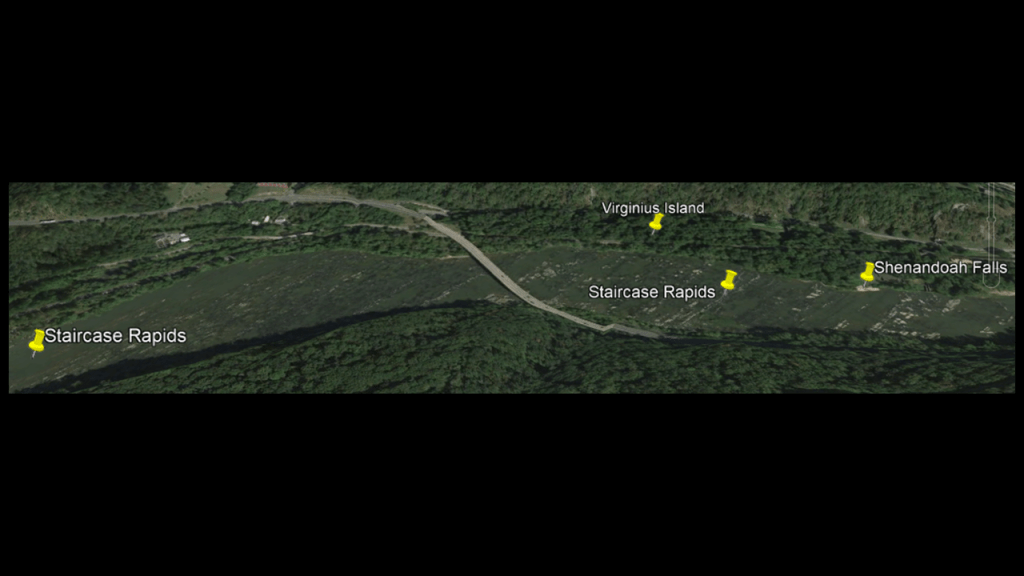

Going from left-to-right along the Shenandoah River in this Google Earth Screenshot, Virginius Island; the Staircase Rapids; Shenandoah Falls, and the original site of the Shenandoah River Bridge.

We are told Virginius Island was a thriving industrial location in the first-half of the 19th-century, after Virginius Island was created by the Patowmack Company when it was constructing the Shenandoah Canal between 1806 and 1807.

Besides the railroad that ran across Virginius Island, other industries that were said to have been here including a wide-range of mills and factories. and that at its peak in 1850, there were 180 people living here in 20 houses.

Here are some of the stone ruins found today on Virginius Island.

Compare the photo on the left taken at Virginius Island in Harpers Ferry identified as “pulp factory ruins;” and on the right, ancient waterwheels found in Faiyum, Egypt.

Next, the “Staircase Rapids.”

What are called the “Staircase Rapids” run along the Shenandoah River a distance through this stretch of the river, consisting of the “Upper Staircase” and the “Lower Staircase,” towards a section of the river classified as “Shenandoah Falls.”

I’m sure I went over these rapids on a group whitewater rafting trip when I was a teenager. I was part of a very active youth group at my church where we went on all of these fun outings together.

Reflecting back on it, these were experiences I would not have otherwise had, and I am grateful that I was able to do them.

Did rapids have a function on the Earth’s grid system too?

More on this thought shortly after I finish looking at what is found around this location, and revisit the subject of rapids on the grid system and look at some other places with a similar set-up as Harpers Ferry with respect to infrastructure at these locations.

There are ruins the ruins of two historic bridges at the confluence of the two rivers – original Shenandoah River Bridge abutments and abutments for the former Bollman Bridge, another railroad bridge that was next to the two existing railroad bridges crossing the Potomac River.

The original Shenandoah River Bridge was said to have first been a wagon-road bridge and later a vehicle bridge that was completely destroyed by one of the 1936 flood, the worst of six known floods starting in 1748.

The 1936 flood crested at 36.5-feet, or 11-meters.

Along with the Shenandoah River Bridge and many businesses in the Lower Town of Harpers Ferry…

…the Bollman Railroad Bridge was completely wiped away in the same flood.

Both ruined bridges were also said to have suffered damage during the Civil War, but rebuilt for use until they were completely wiped out by the floodwaters in 1936.

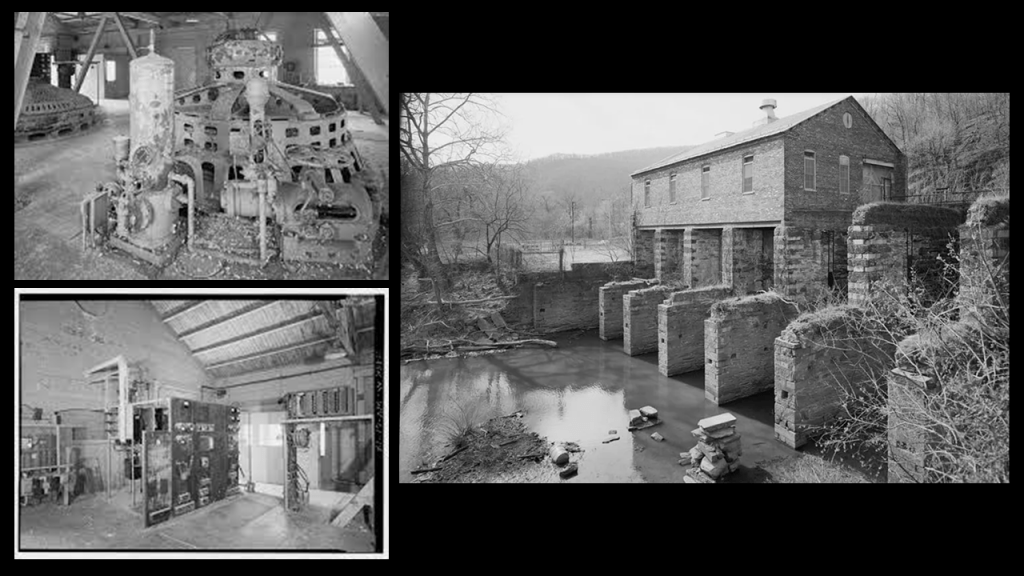

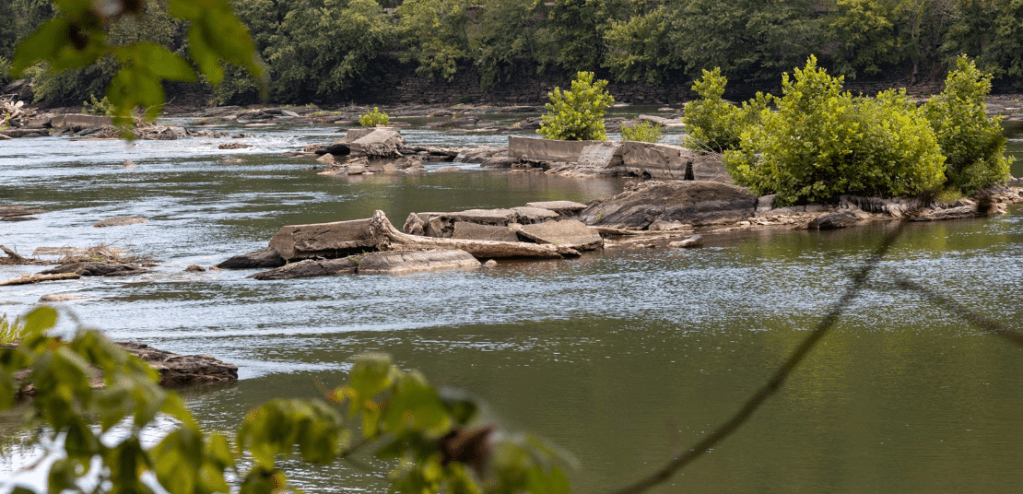

Now heading up the Potomac River from the confluence of the two, the Potomac has rapids through here, as well as a Hydroelectric Power Plant.

It was said to have been built in 1888, and operated from 1899 to 1991, and was originally part of a wood pulp mill, and after a fire in 1925, operated only as a power house.

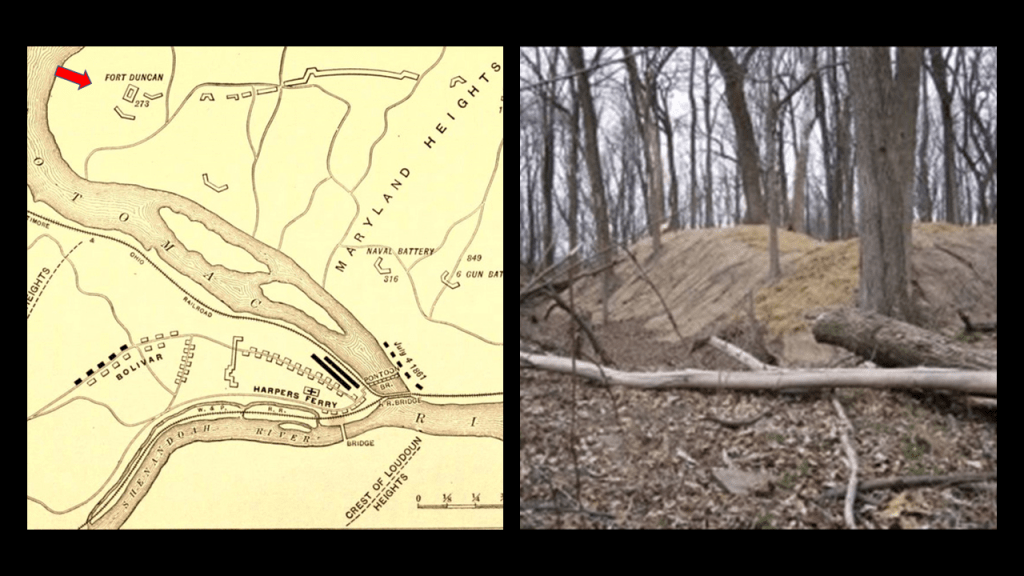

Following the Potomac River from the old power plant ruins, we soon come to Lock 34; Dam 3 ruins; and Fort Duncan.

The railroad tracks follow the Potomac River up until the river bend at the Dam 3 Ruins, and then veer off across the countryside.

The C & O Canal Lock 34 is at mile 61.5 of the canal’s towpath, just north of Harpers Ferry.

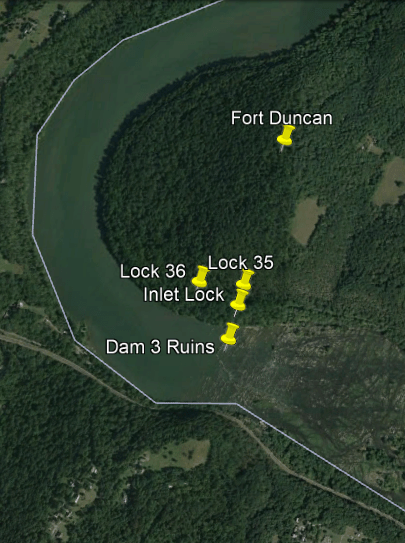

The next place we come to on the Potomac River after Lock 34 are the ruins of Dam 3, an inlet lock, Lock 35, and Lock 36 around mile 62 of the canal towpath.

Dam 3 was said to have been built in 1799 to serve the Armory at Harpers Ferry.

The dam was said to be ineffective; rebuilt once in 1820; and then in 1832, used by the C & O Canal for its purposes.

The Inlet Lock, Lock 35 and Lock 36 are in close proximity to the ruins of Dam 3.

The historical location of Fort Duncan is less than a half-mile north from the location of the Dam 3 ruins and the lock infrastructure, up a steep hill.

It was said to have been constructed by the Union Army in October of 1862 shortly after the Battle of Antietam and the Union surrender of Harper’s Ferry to the Confederate Army under the command of General Stonewall Jackson.

Its stated purpose was to guard the area around Harpers Ferry, the railroad and the canal.

The only action seen there was reported to have been a small demonstration following the Confederate General Jubal Early’s raid on Washington in 1864.

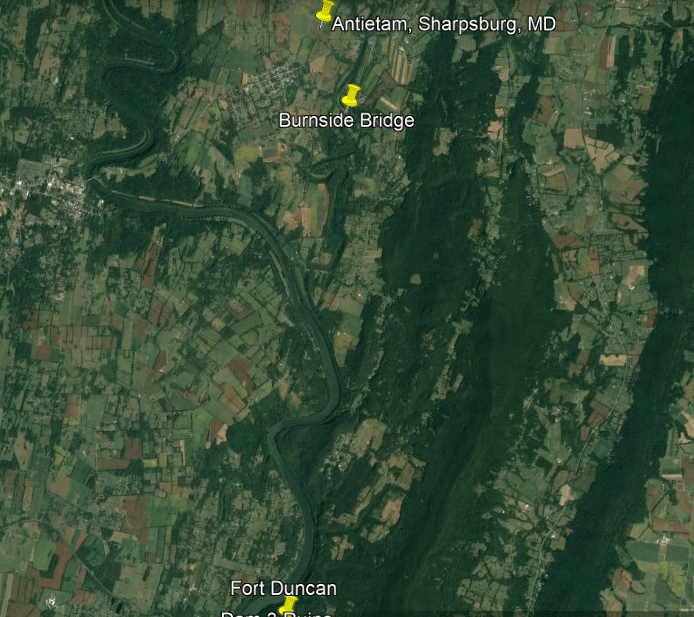

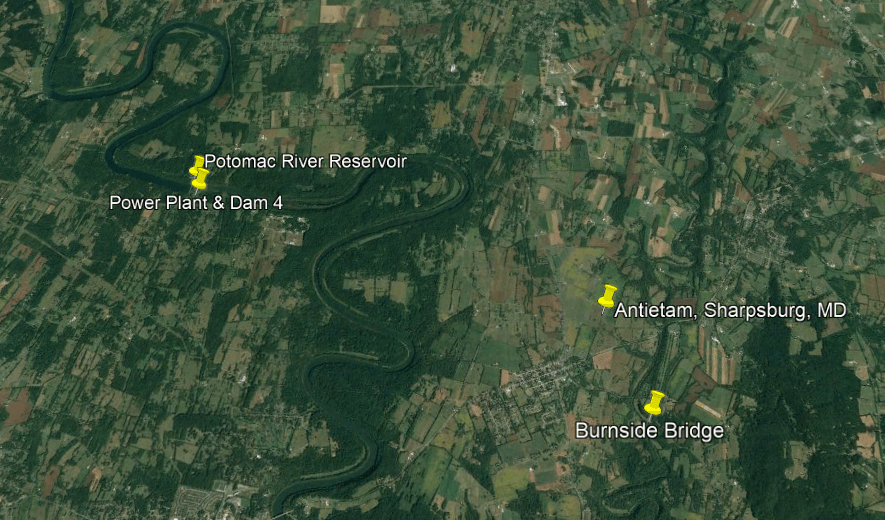

Leaving the historic location of Fort Duncan, we are heading north to the battlefield of Antietam in Sharpsburg, Maryland, and Antietam Creek.

I remember visiting Antietam with my family when I was young, and then went there in 2004 when visiting a friend who lives in the area, and got an up-close and personal with the Burnside Bridge because I photographed it and later painted it.

More on the Burnside Bridge in a moment.

We are told that Antietam was the deadliest one-day battle in American Military History, on September 17th of 1862, with 22,727 dead, wounded, or missing.

The battle was fought between the Confederate troops of General Robert E. Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia and the Union troops of General George McClellan’s Army of the Potomac.

We are told Lee’s Army advanced into Maryland on September 3rd, after their victory on August 30th at the Second Battle of Bull Run in Northern Virginia.

McClellan’s troops were there to intercept them and by September 17th had the Confederate troops in defensive positions behind Antietam Creek.

After a long bloody day of fighting and death, the Union Army succeeded in turning back the Confederate invasion of Maryland, and was considered a major turning point in the war in the Union’s favor.

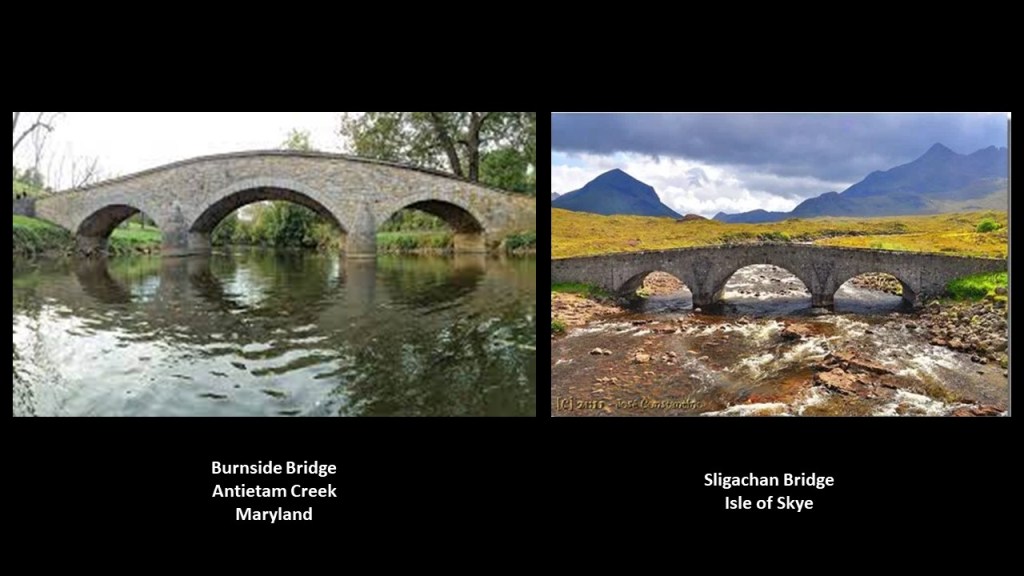

The Battle of Burnside Bridge took place in the afternoon that day to capture the bridge, which was dominated by a wooded bluff on the west bank and strewn with “boulders from an old quarry,” impeding the crossing of the bridge by combatants because this provided good cover.

The attempts of the Union Army troops under the command of Major-General Ambrose Burnside failed to secure the bridge and resulted in a considerable loss of life.

Compare the appearance of the Burnside Bridge on the left with that of the Sligachan Bridge on the Isle of Skye off Scotland’s northwest coast on the right.

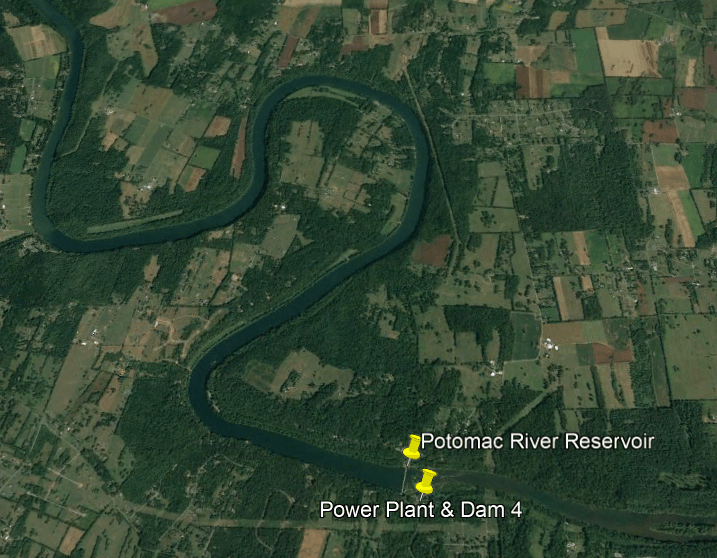

The last section of the Potomac River and C & O Canal I am going to look at is a cluster of Hydroelectric and reservoir infrastructure to the northwest of Sharpsburg and the Antietam battlefield.

There is a series of S-shaped river bends through here that I see all over the Earth and long-believed also have a functional purpose on the Earth’s grid system…

…and you see the same S-Shaped river bends on the Mississippi River where the Battle of Vicksburg in Mississippi was said to have been fought in the Civil War that you have on the Potomac River where the Battle of Antietam was fought.

Coincidental or intentional?

The infrastructure found along the Potomac River and C & O Canal here includes the Power Plant & Dam 4 and the Potomac River Reservoir.

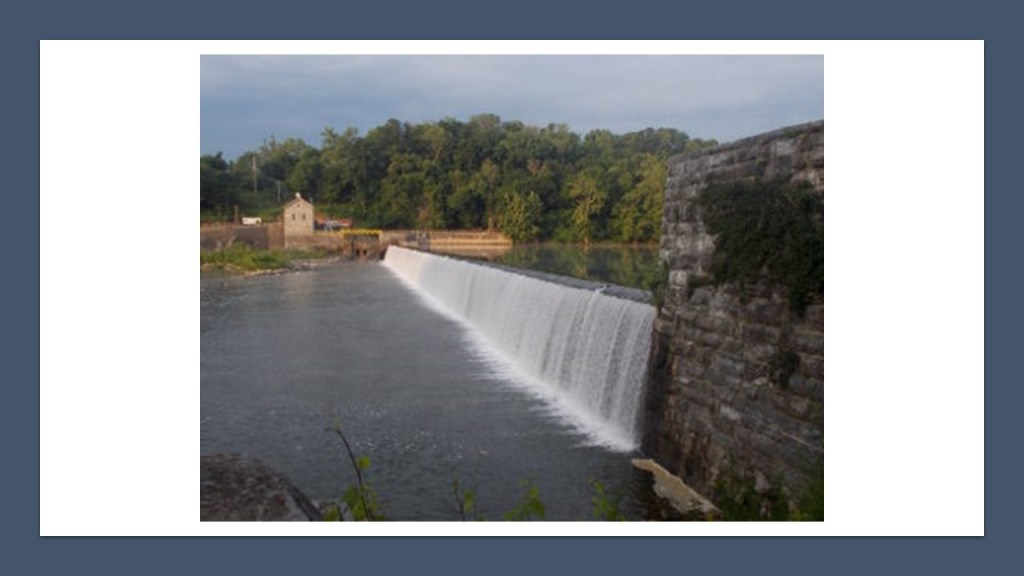

The Power Plant and Dam 4 is an historic hydroelectric power generation station on the Potomac River, and part of the Potomac River Reservoir.

The Power Plant is a limestone building on a high stone foundation built into the hillside. that is five-bays long and a gable-roof said to have been built in 1909.

Dam 4 was said to have originally been built starting in 1832 and completed in 1835 for the C & O Canal, and that it starting supplying hydroelectric power in 1913.

Today it is owned by the National Park Service and leased to the Potomac Edison Electric Company for electric power generation in Washington County, Maryland.

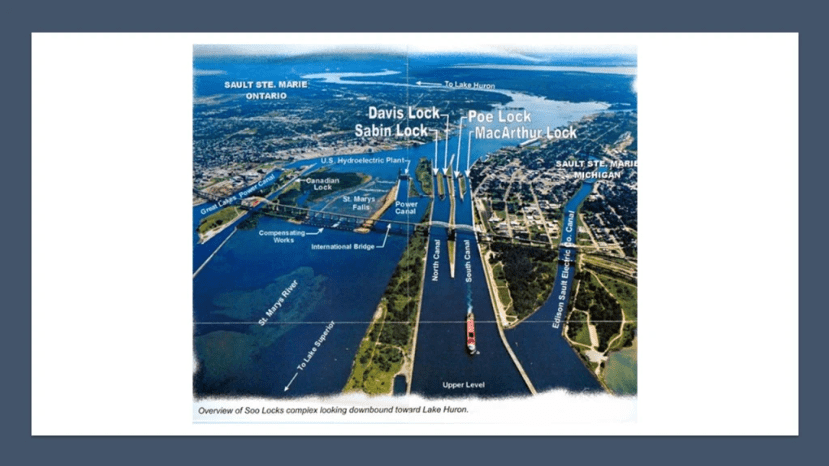

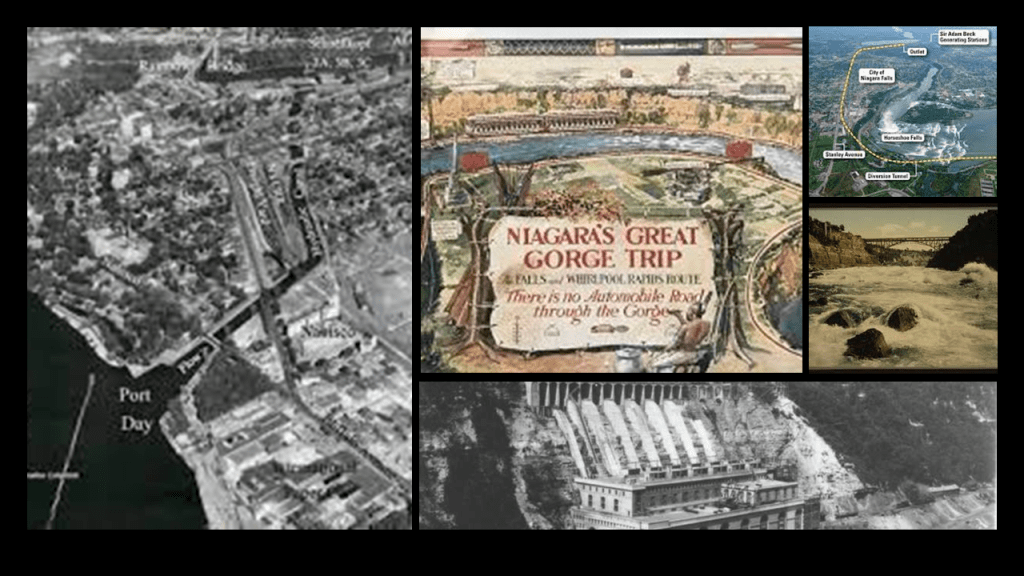

Another example of a place with the same infrastructure found at Harper’s Ferry is”The Soo,” the nickname given to the Sault Stes. Marie of Michigan and Ontario.

The Soo Locks, the largest waterway traffic system on Earth, are called the “Linchpin of the Great Lakes,” allowing ships to travel between Lake Superior and the lower Great Lakes. Lake Superior meets Lake Huron with a 21-foot drop in elevation.

In the two Sault Ste. Maries and in-between them, we find the same infrastructure that is found in and around Harper’s Ferry.

Canals and Locks…

…rapids called the St. Mary’s Falls, two hydroelectric powerhouses, and the Soo Locks all right next to each other…

…bridges, one for cars and one for the railroad…

…other railroad infrastructure…

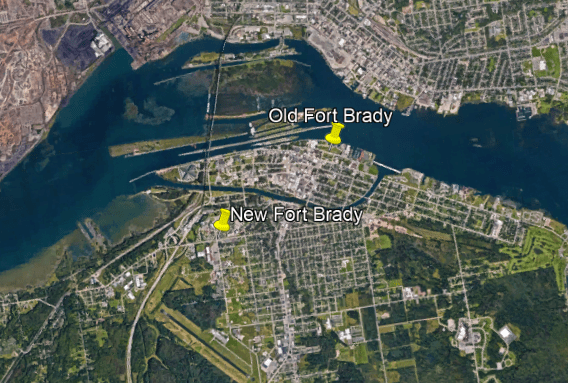

…two historic forts, Old Fort Brady and New Fort Brady, now the campus of Lake Superior State University…

…and things like a historic pulp mill, all examples of infrastructure that is found at Harpers Ferry.

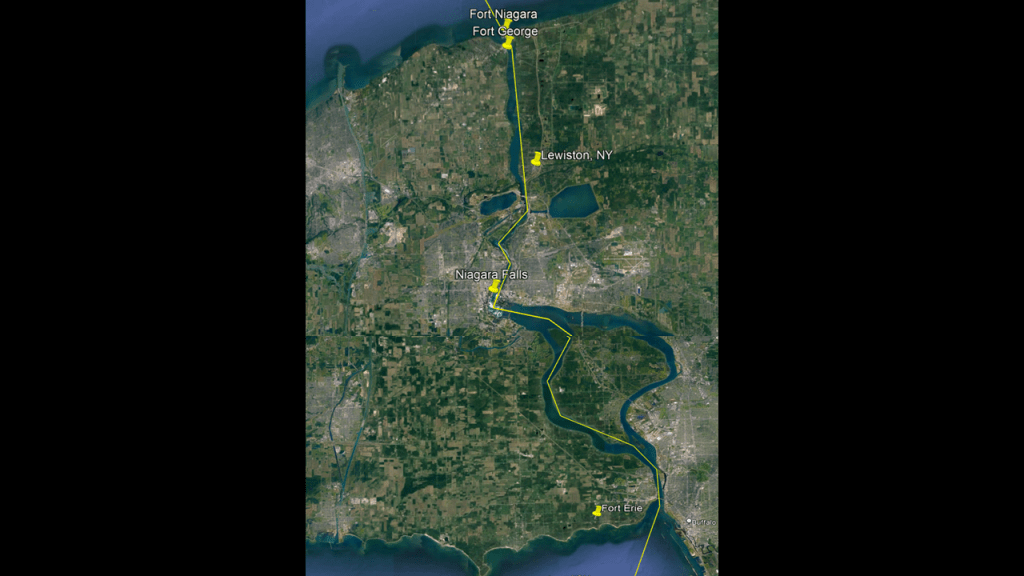

The same infrastructure that is found around Harpers Ferry and The Soo is also found in the Niagara Falls region between New York and Ontario along the Niagara River between Lake Ontario and Lake Erie…

…including historic Fort Niagara in Youngstown, New York, and Fort George in Niagara-on-the-Lake, Ontario, where the Niagara River meets Lake Ontario, and Fort Erie in Ontario is located across the Niagara River from Buffalo, New York, where the river meets Lake Erie.

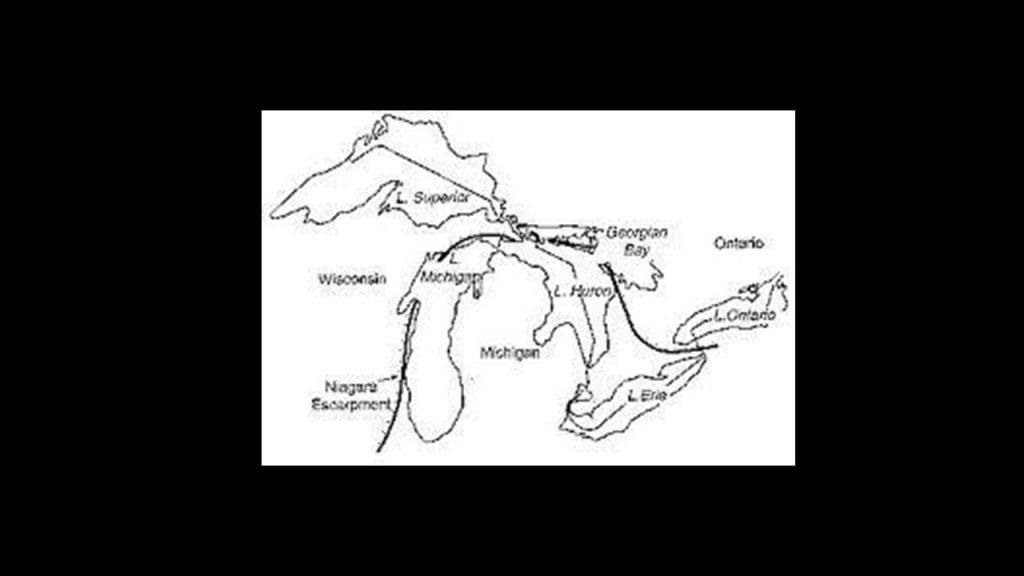

I recently received photos from viewer JW of Inglis Falls on the Niagara Escarpment.

This is what he said in the email:

“I’m in Owen Sound Ontario. Up on Georgian Bay, Lake Huron. I’m on the Niagara Escarpment. I came to a place called Inglis Falls. I took some trails through the forest so I could get to the bottom of the falls rather than the top where the public access leads. I definitely see the evidence of ancient brickwork. It seems to be totally inaccessible. It’s at the bottom of the Cliff face but I can’t cross that River to get there because it is too dangerous.”

Is this first-hand evidence that the Niagara Escarpment was man-made?

It is interesting to note what we are told about the origin of the Niagara Escarpment.

It is the most prominent of several escarpments in the bedrock running from eastern Wisconsin north through Northern Michigan, curving around southern Ontario through the Bruce Peninsula and Manitoulin Island and other islands in northern Lake Huron, before extending eastwards across the Niagara region between Ontario and New York, and formed over millions of years ago through weather and stream erosion through rocks of different hardnesses.

That’s what they tell us, anyway!!

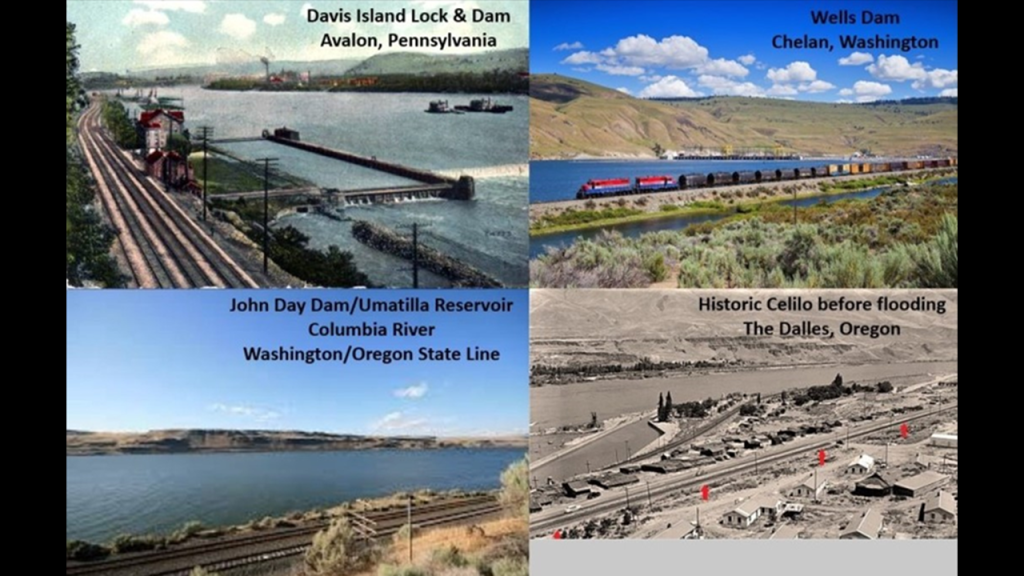

Also with regards to the co-location of railroad lines and hydroelectric projects, I have encountered numerous examples in past research, like the Davis Island Lock and Dam in Avalon Pennsylvania on the top left; the Wells Dam in Chelan, Washington o the top right; the John Day Dam and Umatilla Reservoir on the Columbia River between Washington and Oregon; and the historic site of Celilo which was submerged by rising waters from The Dalles dam in 1957, and prior to that was the economic and cultural hub of Native Americans in the region, and said to be the oldest continuously inhabited settlement in North America.

On to more examples of these connections.

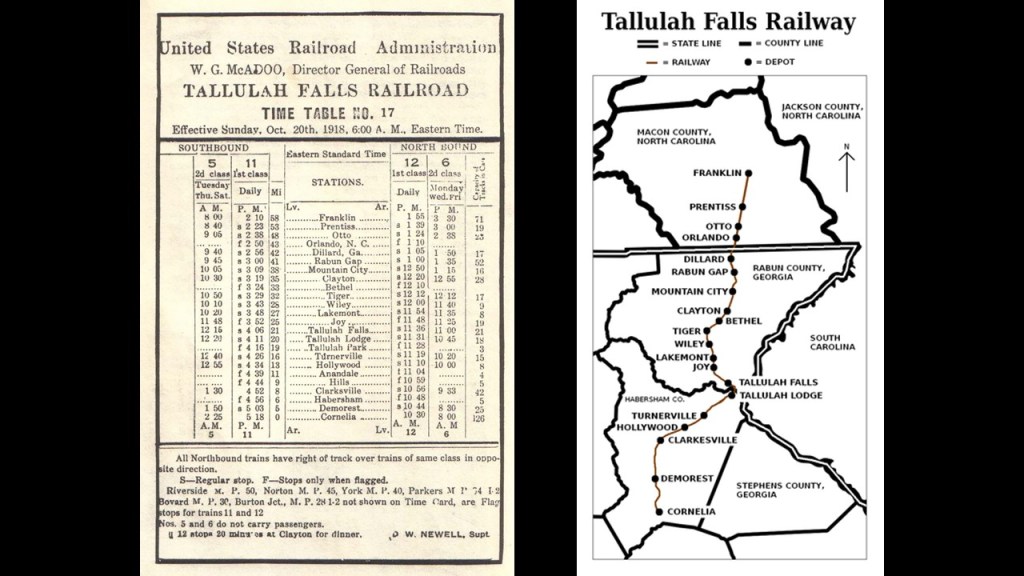

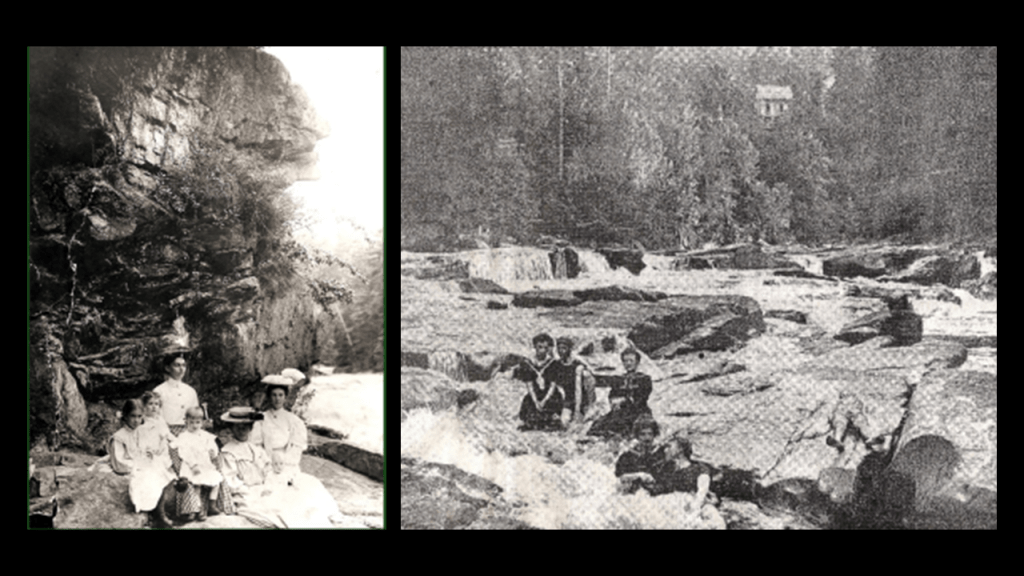

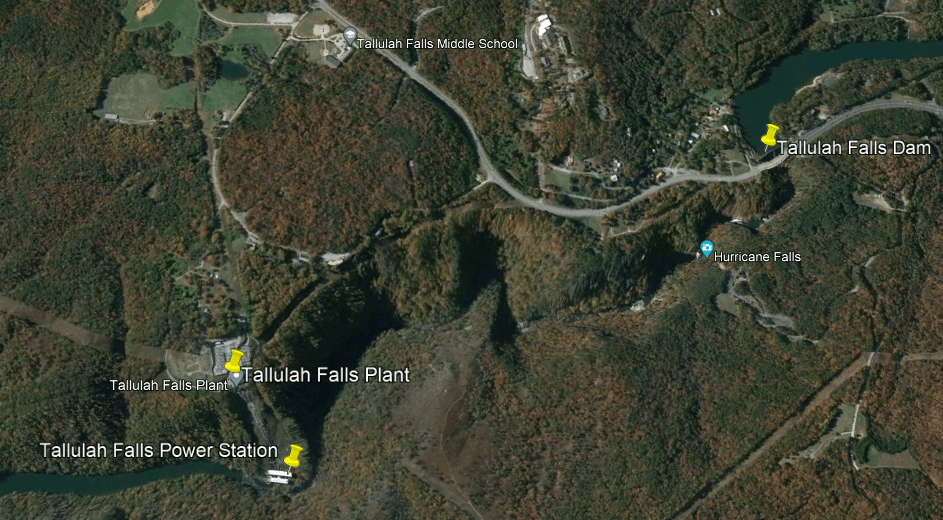

Next, I am going to take a look around the Tallulah Gorge and Tallulah Falls in North Georgia close to where it meets the South Carolina State Line.

A State Park since 1993, the major attractions of the park are the 1,000-foot, or 300-meter, deep Tallulah Gorge; the Tallulah River which runs along the flood of the gorge; and six major waterfalls known as the Tallulah Falls which cause the river to drop 500-feet, or 152-meters, over one-mile, or 1.6-kilometers.

This is what we are told.

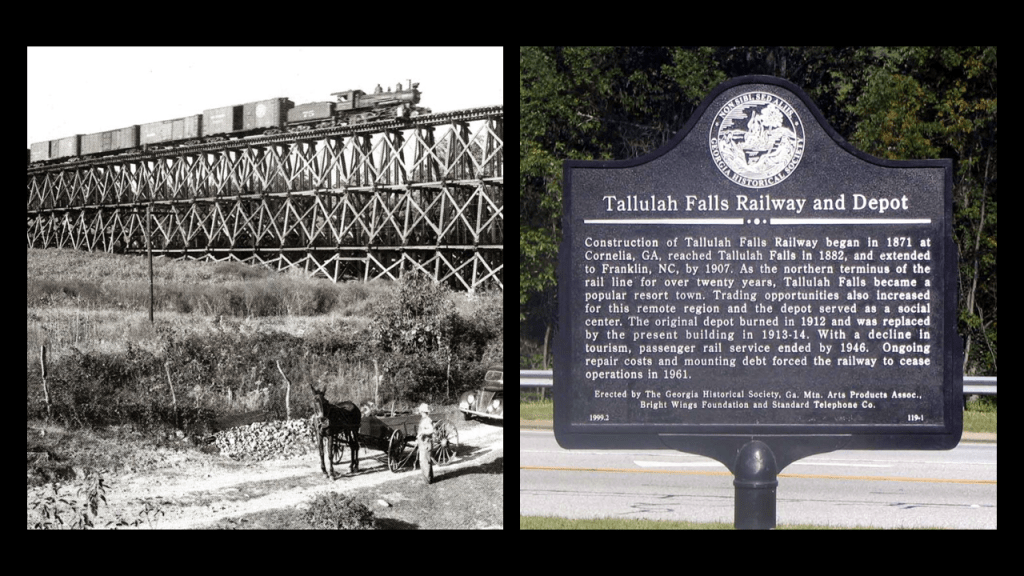

In 1854, The General Assembly of the State of Georgia first enacted legislation for the construction of a railroad linking the towns of Athens and Clayton in North Georgia, and the railroad opened in sections starting in 1870, with construction of the railroad having been delayed with the outbreak of the Civil War between 1861 and 1865.

When the railroad arrived at Tallulah Falls in 1882, tourism to the area intensified, bringing thousands of people a weeks to the area.

At one time, there were seventeen restaurants and boarding houses here catering to wealthy tourists.

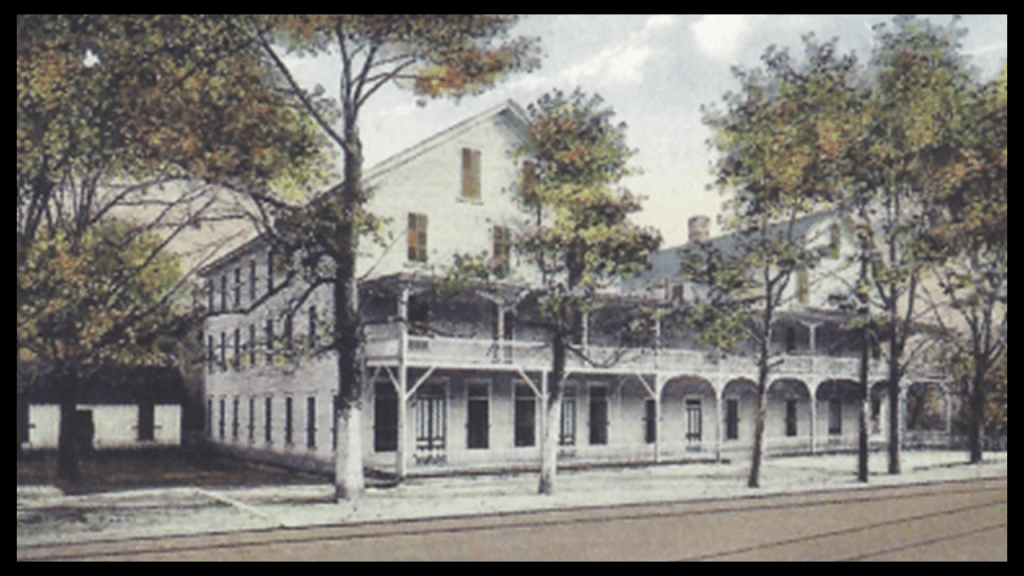

Places like the Tallulah Lodge, said to be the grandest lodge at Tallulah Falls with over 100-rooms and built in the 1890s, and located one-mile, or 1.6-kilometers, south of the depot on the rim of the gorge.

The Tallulah Lodge burned down in 1916.

There was an historical fire in Tallulah Falls in 1921 that wiped out almost the entire town.

The Cliff House boasted 50-rooms and was located on the edge of the gorge across the tracks from the train depot, and was said to have been built in 1882.

When it finally burned down in 1937, all the grand hotels and boarding houses were gone.

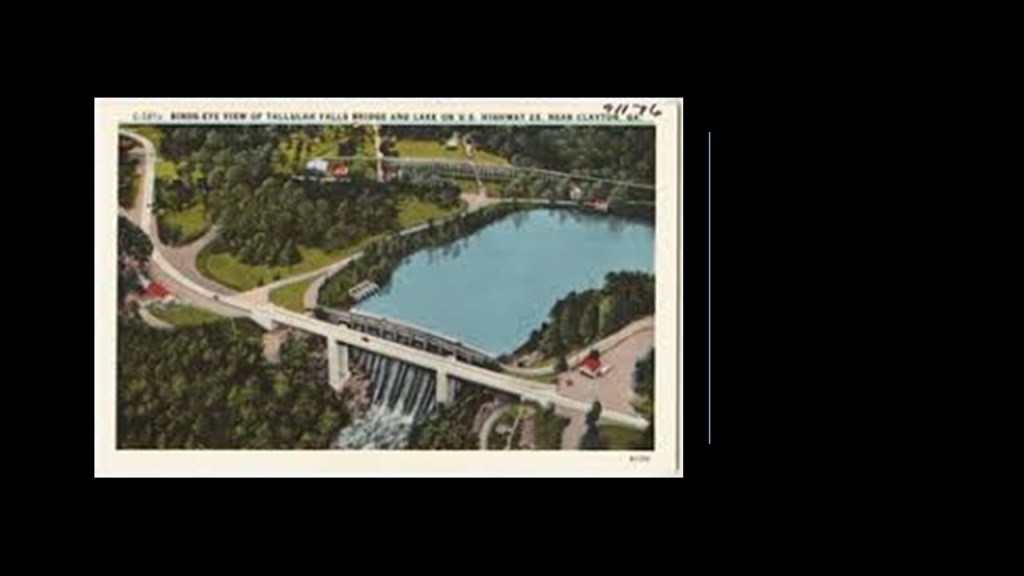

We are told that starting in 1909, the Georgia Railway and Power Company, had scouted the Tallulah River and Gorge with its drop in elevation as the ideal place to construct a dam and hydroelectric plant in order to provide electrical power to Atlanta, and that it ended up being one of six being constructed along a 26-mile, or 42-kilometer, stretch of the Tallulah and Tugaloo Rivers with a 1,200-foot, or 366-meter, drop in elevation, between 1913 and 1927.

The construction of the dam Tallulah Falls was said to have started in 1910 with the purchase of land at the rim of the Tallulah Gorge, and completed in 1914 after the company won a legal battle to halt its activities in the Tallulah Gorge.

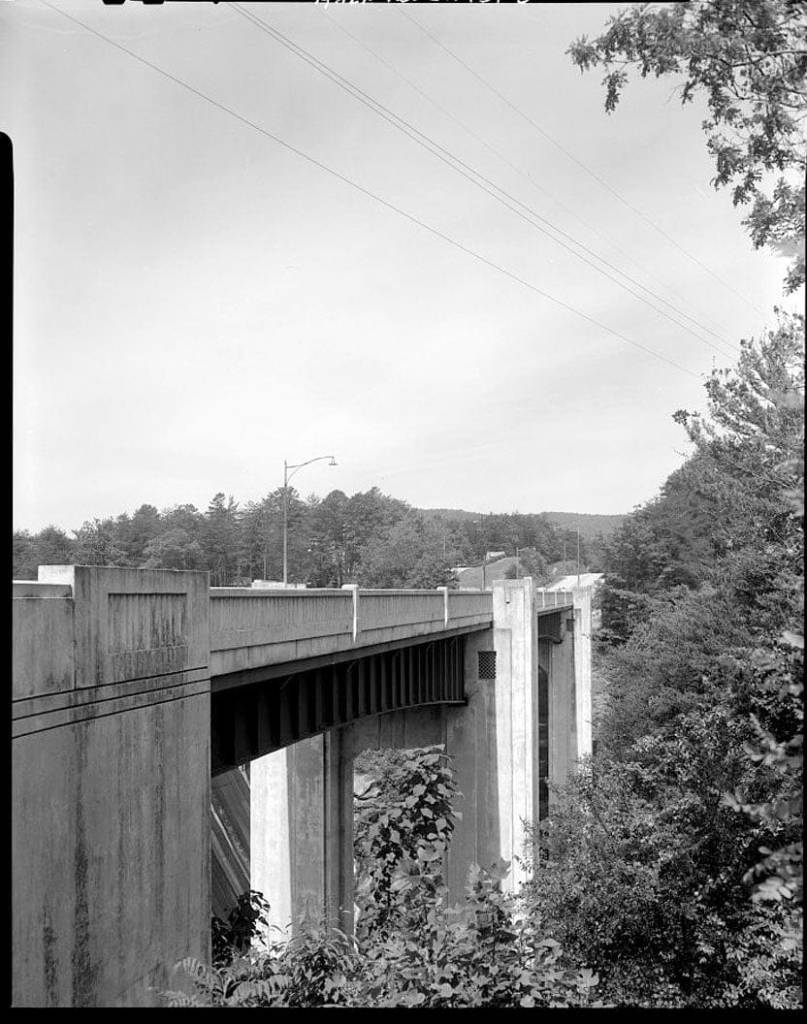

Here is a postcard with the Tallulah Falls Bridge on U. S. Highway 23/State Road 15 crossing right in front of the dam and the Lake Tallulah Reservoir.

The bridge was said to have been built between 1938 and 1939.

The Tallulah Falls Hydroelectric power plant is 685-feet, or 185-meters, lower than the dam.

Water from the Lake Tallulah Reservoir is directed to the power plant by a 6,666-foot, or 2,032-meter, long diversion tunnel that is 11-feet, or 3.4-meters-wide, and 14-feet, or 4.3-meters, high.

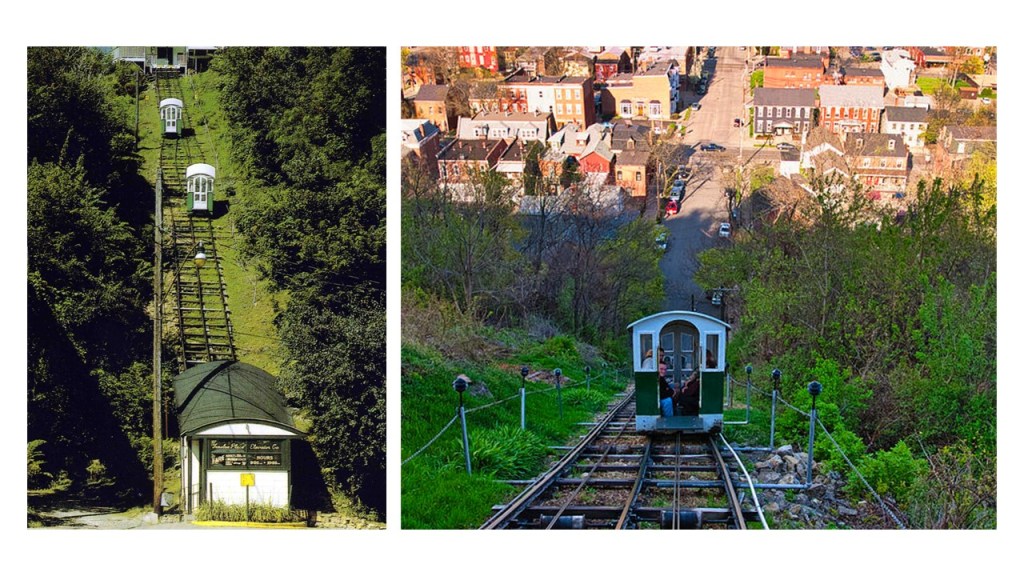

The power station located on the floor of the Tallulah Gorge below the power plant is best accessed for its workers by an incline railway.

I am starting to get curious about the U. S. Highway system, and its relationship to the Earth’s original energy grid system.

As I mentioned previously, the Tallulah Falls Bridge on U. S. Highway 23 crosses right in front of the Lake Tallulah Reservoir and Dam.

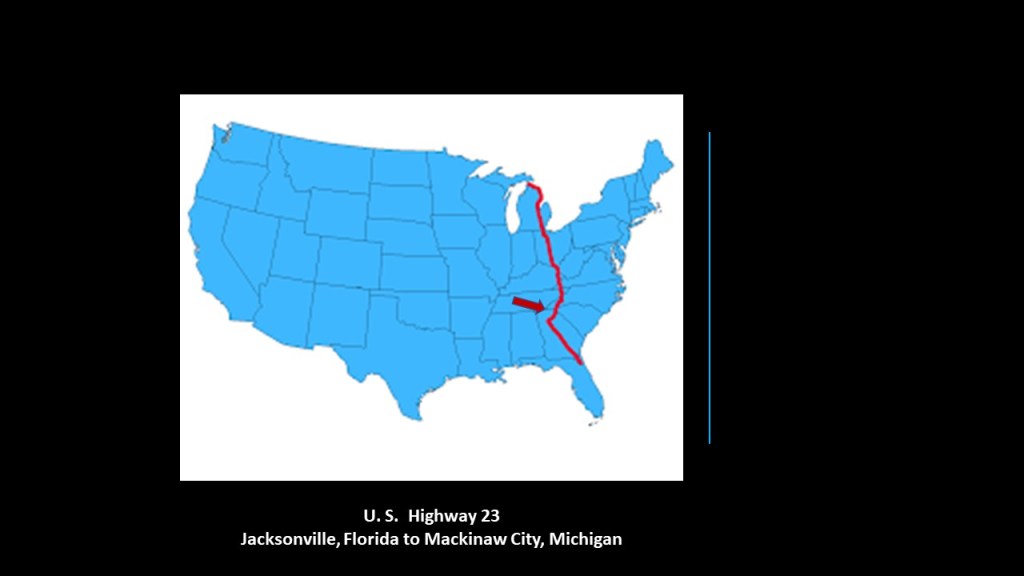

U. S. Highway 23 is a major North – South U. S. Highway between Jacksonville, Florida, and Mackinaw City, Michigan.

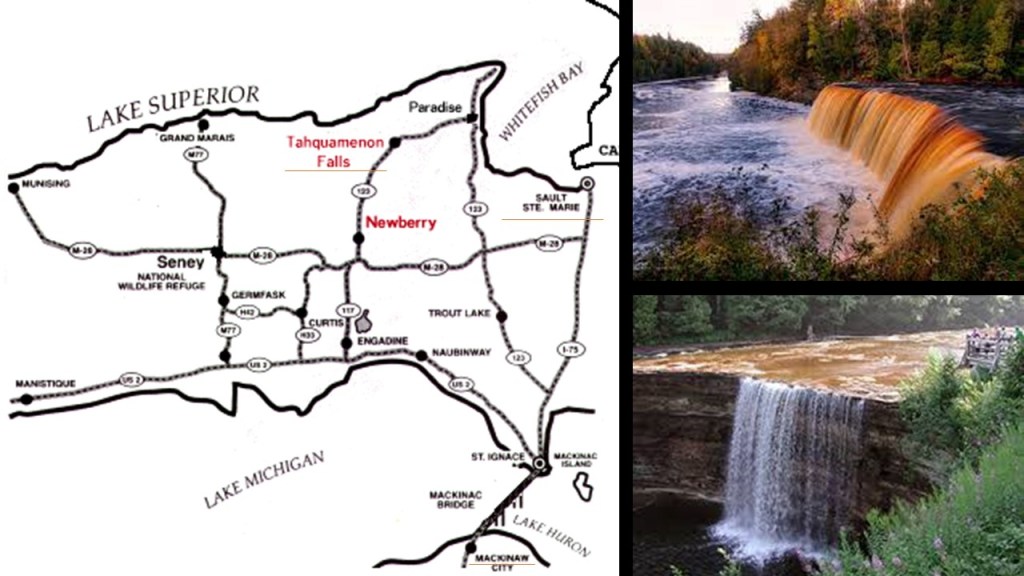

Mackinaw City is not far from the location of the Tahquamenon Falls State Park, where there are a series of waterfalls on the Tahquamenon River before it empties into Lake Superior in the northeastern part of the Upper Peninsula of Michigan, and the Tahquamenon Falls are even closer to “The Soo” region mentioned previously.

Was there an historical rail presence at Tahquamenon Falls?

I searched and what came up was the “Tahquamenon Falls Riverboat Tours & Toonerville Trolley.”

It is a 6 1/2-hour wilderness tour that starts at Soo Junction that includes a narrow-gauge train ride and riverboat cruise to the Falls.

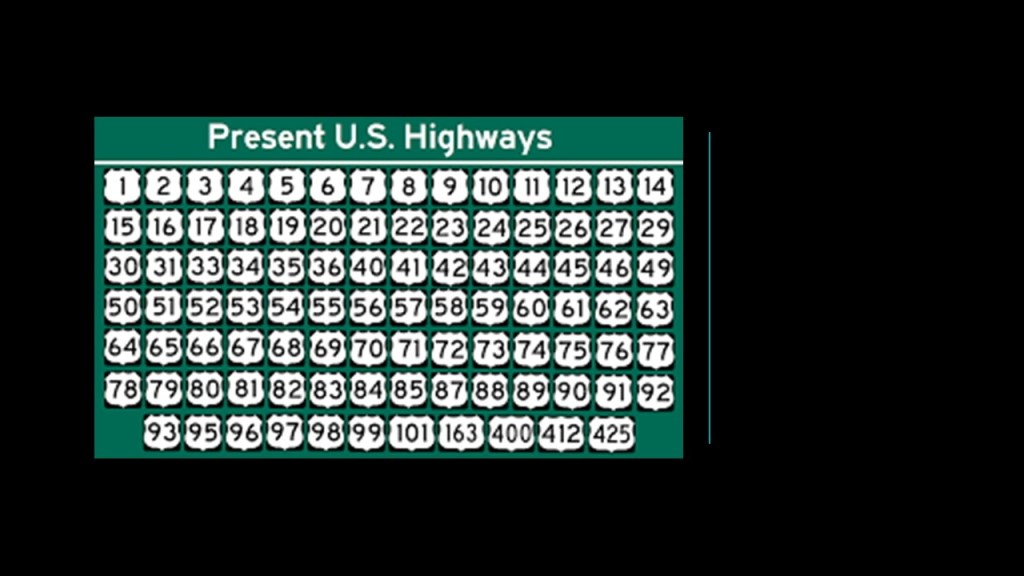

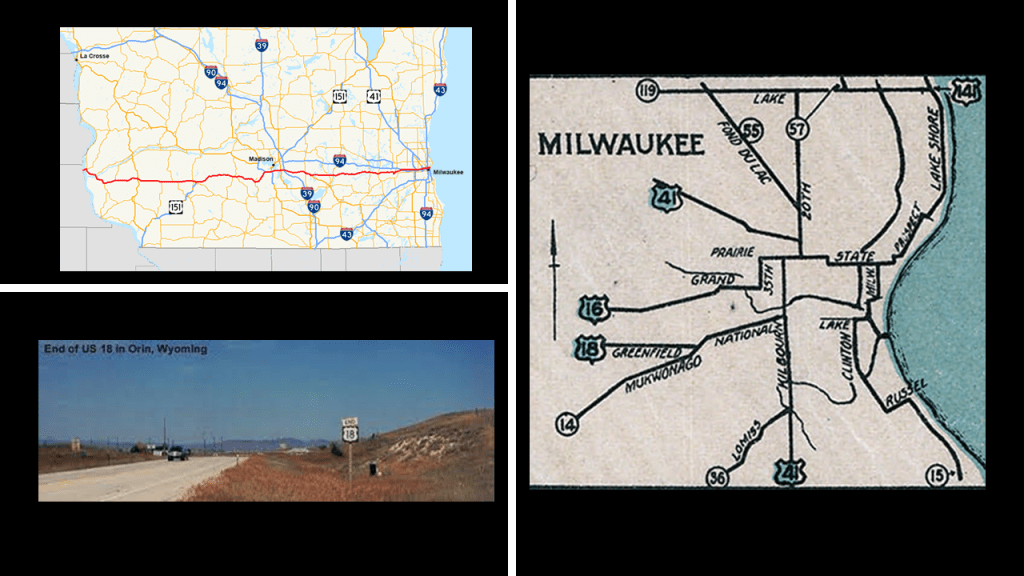

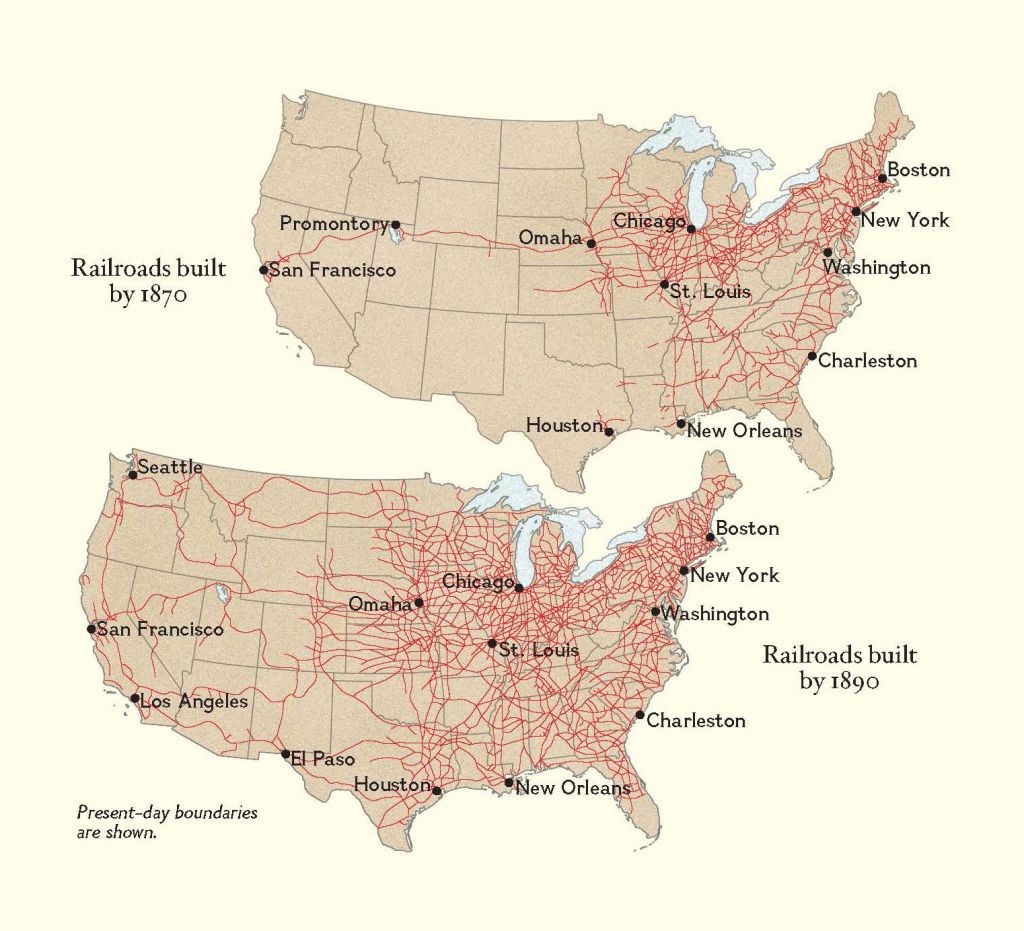

This information about U. S. Highway 23 going from Florida to Michigan connected with at least two major waterfall systems and corresponding historic rail systems led me to look into the United States Numbered Highway System, or the Federal Highway System and am wondering if this was likely a part of the energy grid systemof the original civilization.

It was actually called an integrated network of roads and highways numbered within a nationwide grid across the contiguous United States that was first approved in 1926.

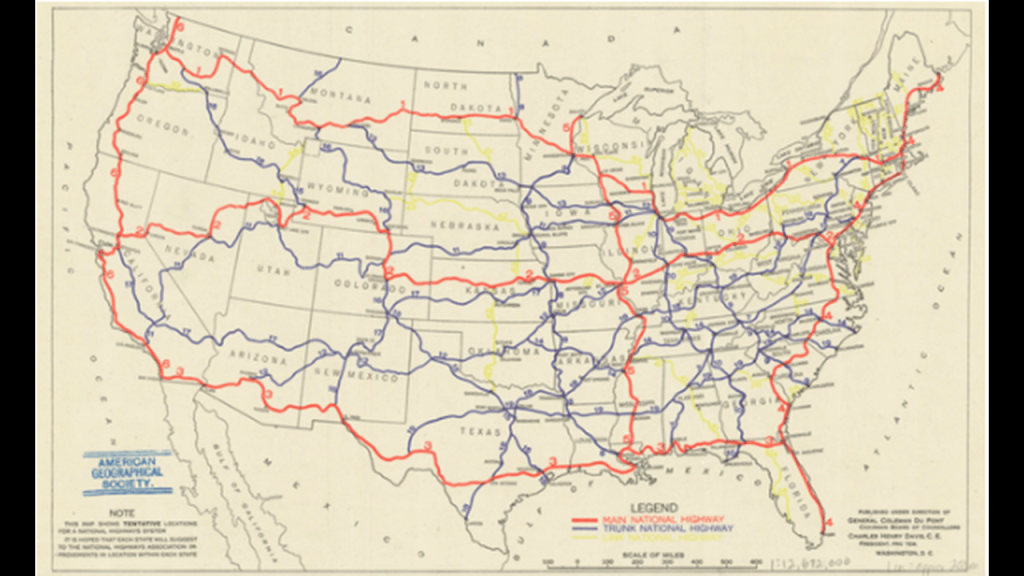

The map was said to be the first proposed U. S. Highway Network map, drawn up by the National Highway Association in 1913.

The red roads were delineating “Main” National Highways; the blue roads “Trunk” National Highways; and the yellow roads were “Link” National Highways to connect all the “Mains” and “Trunks.”

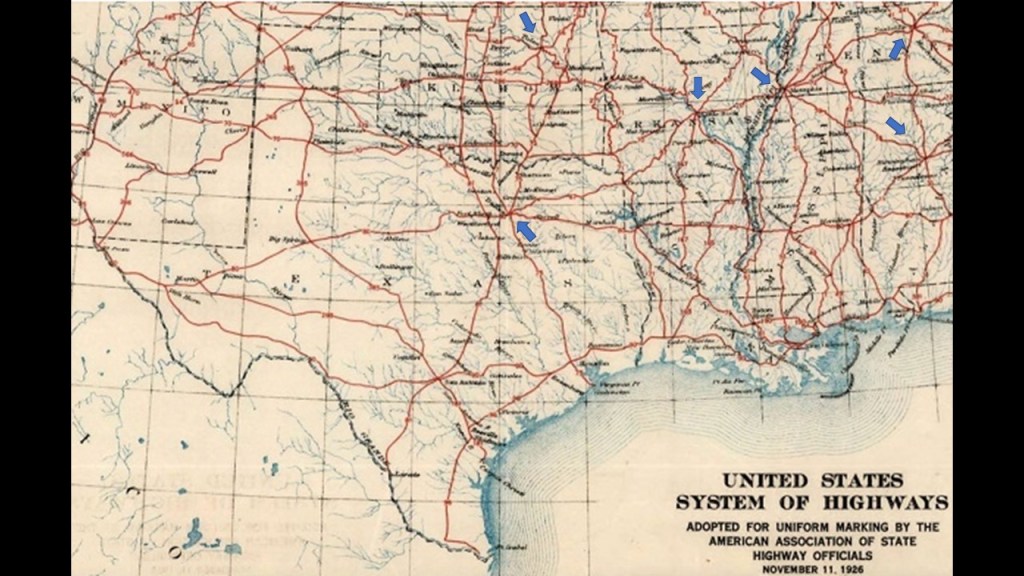

The Nation’s first Federal Highways would not be adopted until 1926, when the American Association of State Highway officials approved the first plans for the numbered highway system, with this section showing Texas, Oklahoma, Tennessee, Arkansas, Louisiana and Mississippi.

I have blue arrows point to major cities that are the central point of at least five highways – Dallas, Texas; Tulsa, Oklahoma; Little Rock, Arkansas; Memphis, Tennessee; Nashville, Tennessee; and Birmingham, Alabama.

Looking just like Petersburg, south of Richmond, Virginia, as the Central point of multiple rail-lines emanating from it in all directions.

Petersburg, Richmond, and points all around here were hot spots during the Civil War.

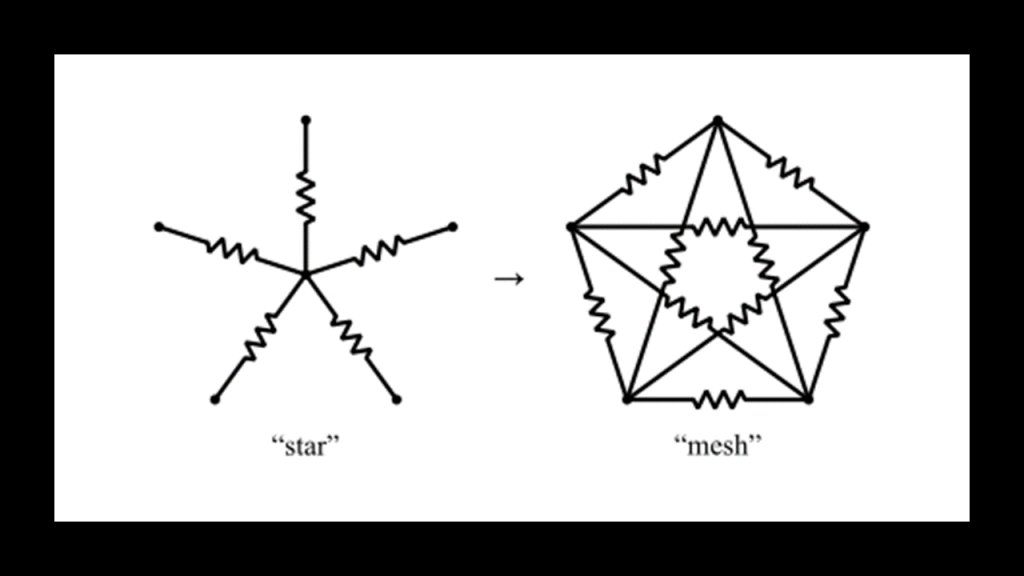

I searched for “star circuit” and the “star-mesh transform” came up.

I don’t know if this is a match for what this was, but I am curious if these large cities as center-points in this configuration of at least five highways or rail-lines have a correlation to a type of circuitry on the Earth’s grid system.

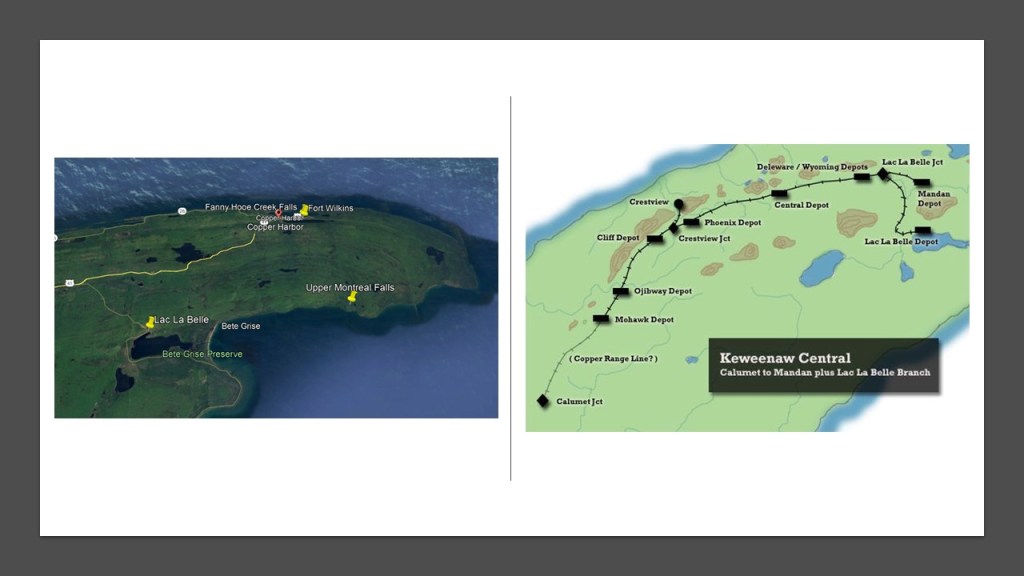

Before I leave the State of Michigan, I am aware from past research of the Upper Montreal Falls on the Keweenaw Peninsula’s Montreal River.

These particular falls are located not far from Lac La Belle, which at one time was a railroad depot on the Keweenaw Central Rail Line, as shown in the map on the right.

On my way out to the last place that I am going to take a look at northern California, I am going to visit past research suggested by JG that I did in “Interesting Comments & Suggestions I have Received from Viewers – Volume 4.”

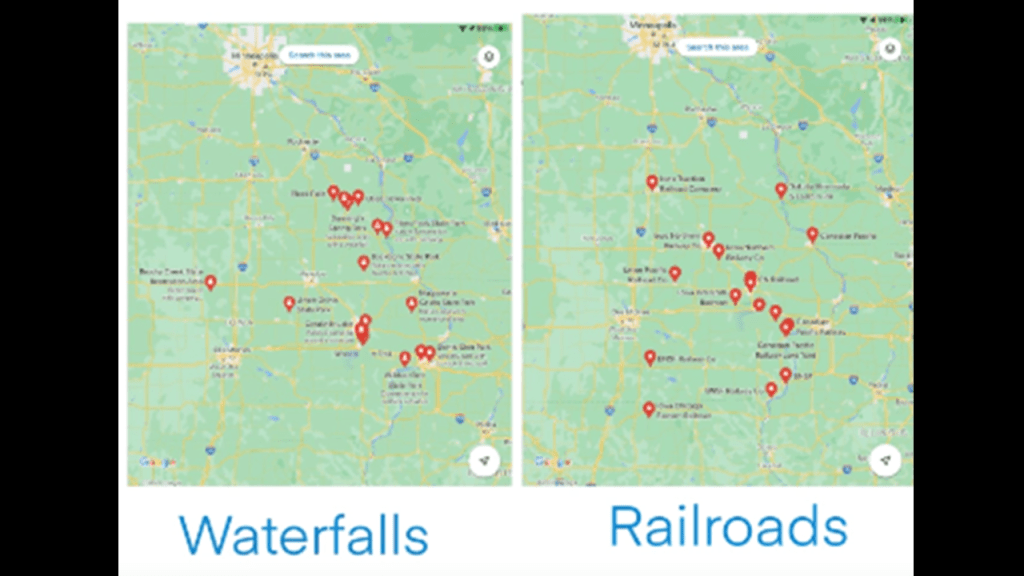

Several years ago, JG connected with me about correlations she had found between railroads and waterfalls in Iowa.

She sent google maps showing the locations of railroads and state parks with waterfalls, and racetracks, as well as another set of maps with more key things like the locations of powerplants, mines and sports stadiums.

I am going to focus in this post on the correlations between railroads and waterfalls that she sent me as a grouping.

Much of the part of Iowa being looked at here is where Iowa, Minnesota, Wisconsin and Illinois meet, and is in part of what is called the “Driftless Area.”

This part of North America is called the “Driftless Area” because it was said to have been by-passed by the last glacier on the continent and lacks glacial drift.

I looked for correlations between the state parks with waterfalls and railroads starting here at the upper section of the previous Google Earth screenshot.

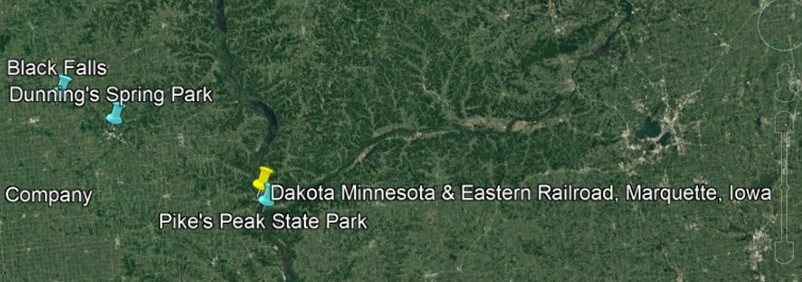

In the top middle, is Black Falls and Dunning’s Spring Park.

Black Falls is near Kendallville, Iowa.

For all of the following waterfalls, I am going to point out with red arrows what looks like an old wall, or old masonry, to me.

There are three waterfalls at Dunning’s Spring just southeast of Black Falls, near Decorah, Iowa…

…one of which is located near the Decorah Ice Cave, a limestone and dolomite cave that has ice on the inside even during the summer…

…as well as the falls at Siewer’s Springs near Decorah, described as “technically a spillway, but a gorgeous staircase formation….”

…and the Malanaphy Spring Falls, northwest of Decorah.

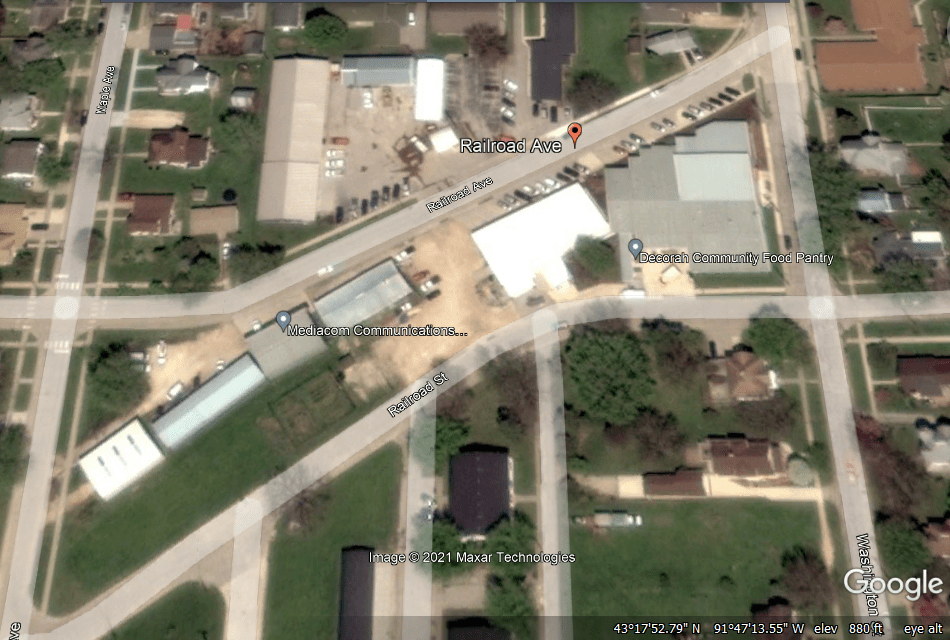

I looked for rail-related infrastructure near Decorah, which now only has Railroad Street and Railroad Avenue, with the Mediacom Communications facility sandwiched between the two…

…and what was the Milwaukee and St. Paul Railway Combination Depot in Decorah is now commercial space, and all the railroad tracks through here were removed in 1971.

From where Black Falls and Dunning’s Spring are at the top of the Google Earth screenshot, next I am going to go southeast of there to “Pike’s Peak State Park.

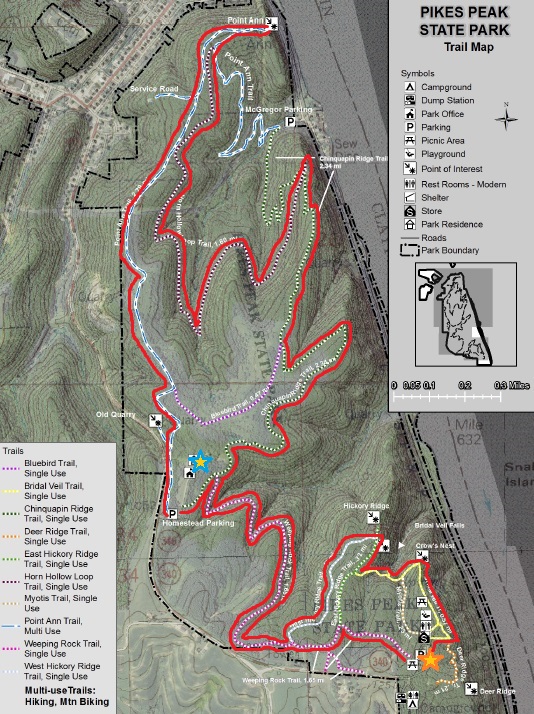

Pike’s Peak State Park in McGregor, Iowa, is situated on a 500-foot, or 150-meter, bluff overlooking the confluence of the Mississippi and Wisconsin Rivers.

It is a recreational area that is considered one of Iowa’s premier nature destinations…

…where one of the places you can hike to is called Bridal Veil Falls.

Bridal Veil Falls is described as “a small natural waterfall that flows gracefully out of a horizontal limestone outcropping.”

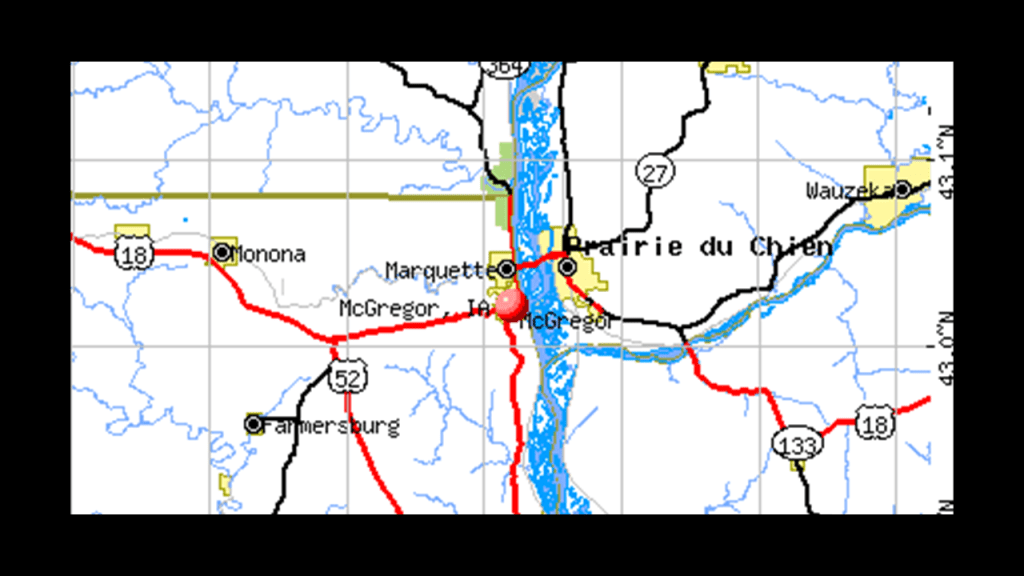

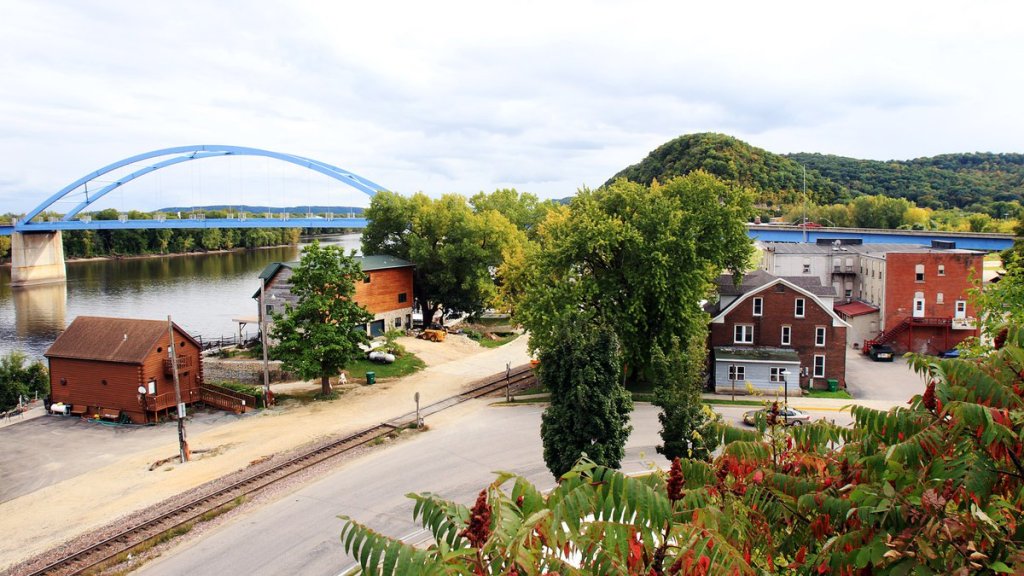

Pike’s Peak State Park and McGregor, Iowa, are right next to Marquette, Iowa, on the Mississippi River, right across from Prairie de Chien, Wisconsin.

Marquette is connected to Prairie du Chien via the Marquette-Joliet Bridge, taking U. S. Route 18 from Iowa to Wisconsin.

It is a cable-supported tiered-arch bridge, with the ends of the arch supported by two abutments in the middle of the river.

U. S. Route 18 is one of the original U. S. Highways of 1926.

Its western terminus is in Orin, Wyoming, and its eastern terminus is in downtown Milwaukee.

Back in Iowa, Marquette earlier in history was known as North McGregor, and served as a railroad terminus, becoming a major railroad hub for the region in its hey-day.

Passenger service ended in 1960, and the Marquette Depot Museum and Information Service in Marquette celebrates the town’s railroad history with exhibits of historic railroad artifacts…

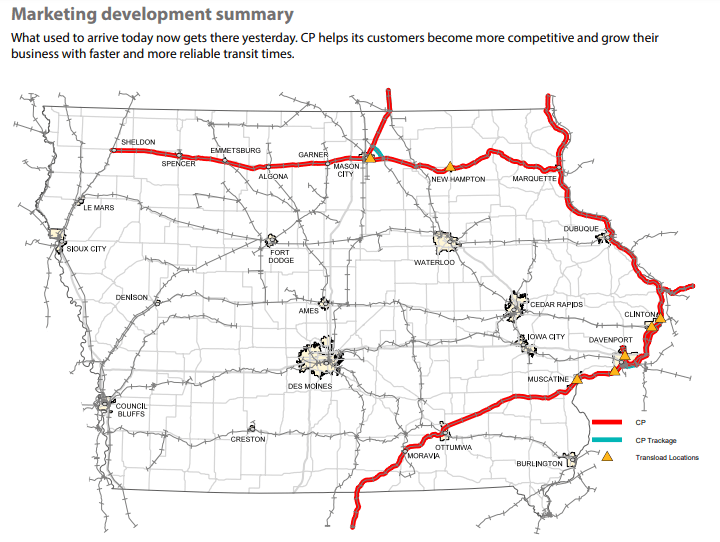

…though the Dakota, Minnesota and Eastern Railroad, a subsidiary of Canadian Pacific Railway, still runs freight on the rail-lines through here.

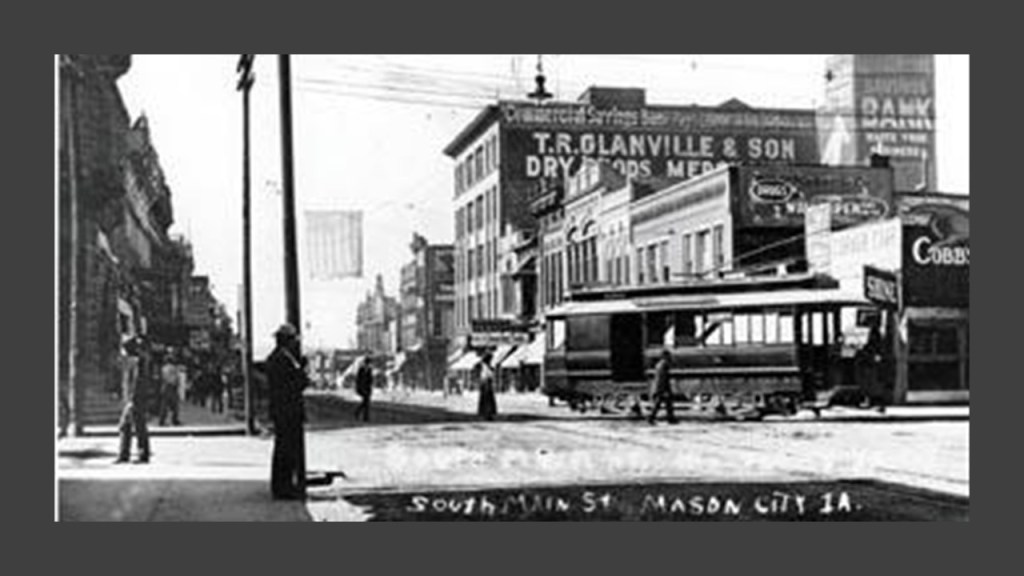

Next, I am going to go due west from Marquette and McGregor over to Mason City, which is connected by the same Canadian Pacific Rail-line to Marquette.

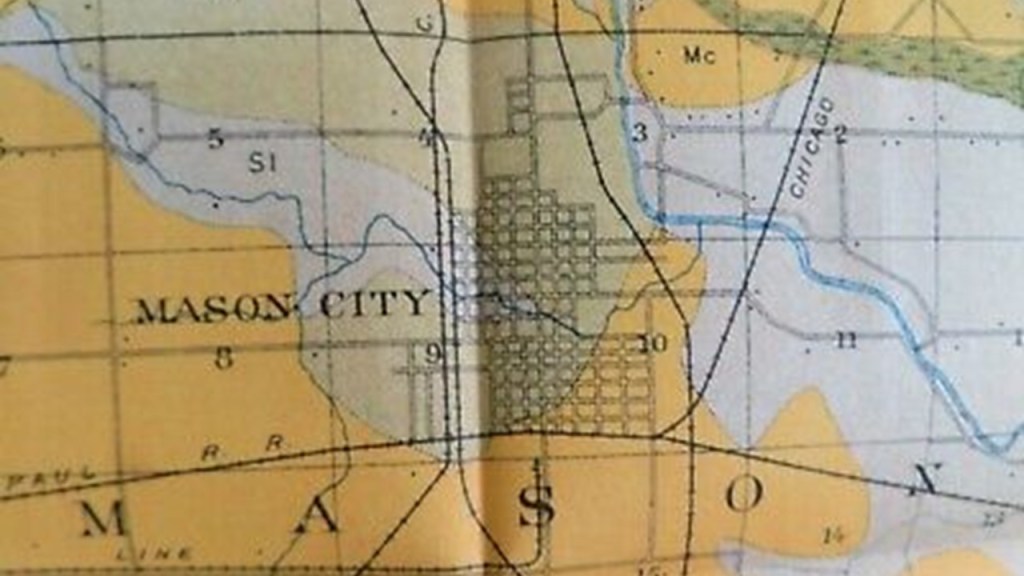

Mason City is located on the Winnebago River, and the name of the original settlementthat was established here in 1853 was “Shibboleth.”

It was also known as Mason Grove and Masonville, until, we are told, Mason City was adopted in 1855, in honor of a founder’s son, Mason Long.

Interesting to note that the original name for the settlement, Shibboleth, is also a Freemasonic password.

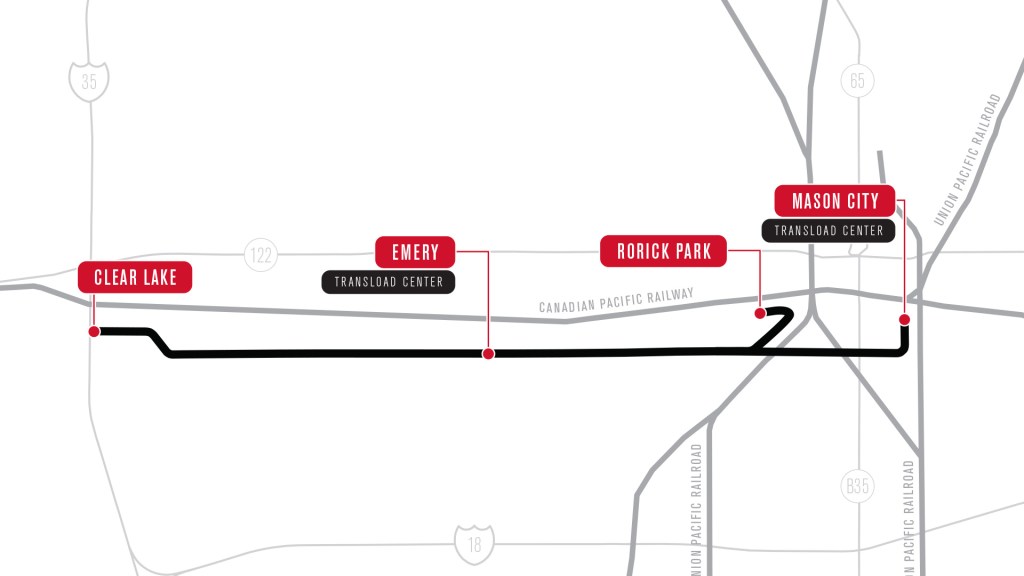

The “Iowa Traction Railroad Company,” headquartered in Emery, west of Mason City, operates a short-line rail-line, that is around 10-miles, or 17-kilometers, -long freight railroad between Mason City and Clear Lake, Iowa, that interchanges in Mason City with the Canadian Pacific Railway and Union Pacific Railway.

It is electrified, which means that an electrification system supplies electric power to the railway, as opposed to an on-board power source or local fuel supply…

…and at one time was part of the electric trolley and interurban system of the region, with the charter for the trolley system expiring in August of 1936, and replaced by passenger bus service the following January.

I did find a waterfall in Mason City, though it is on private property and not in a state park.

Called the “Willow Creek Waterfall,” it can be viewed from the State Street Bridge between 1st Street NE and S. Carolina Avenue in Mason City.

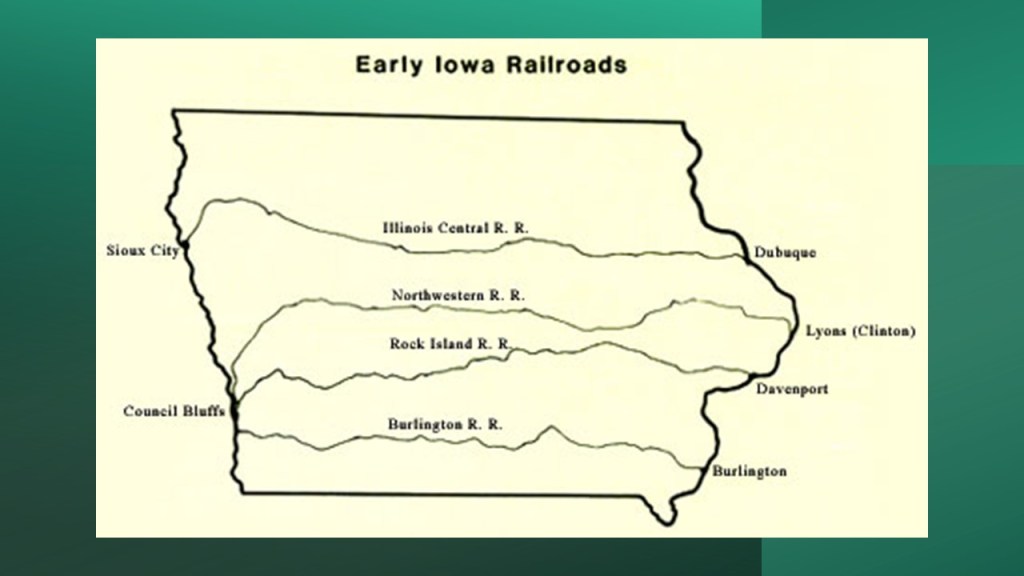

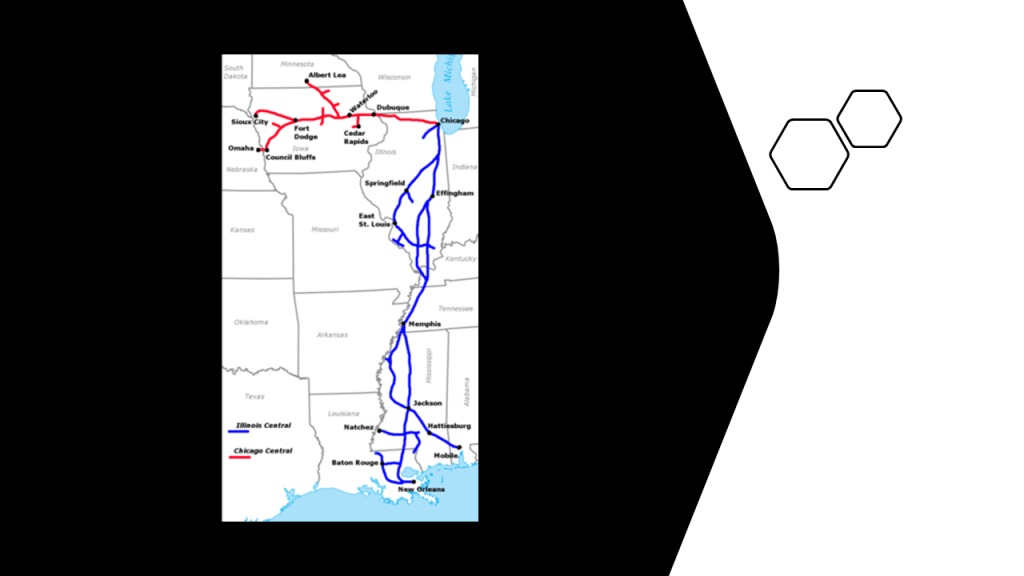

The Illinois Central Railroad ran through Iowa between Sioux City and Dubuque, one of four railroads authorized by Congress via the “Act of 1856…”

…connecting that part of Iowa by rail to Chicago sometime around 1870.

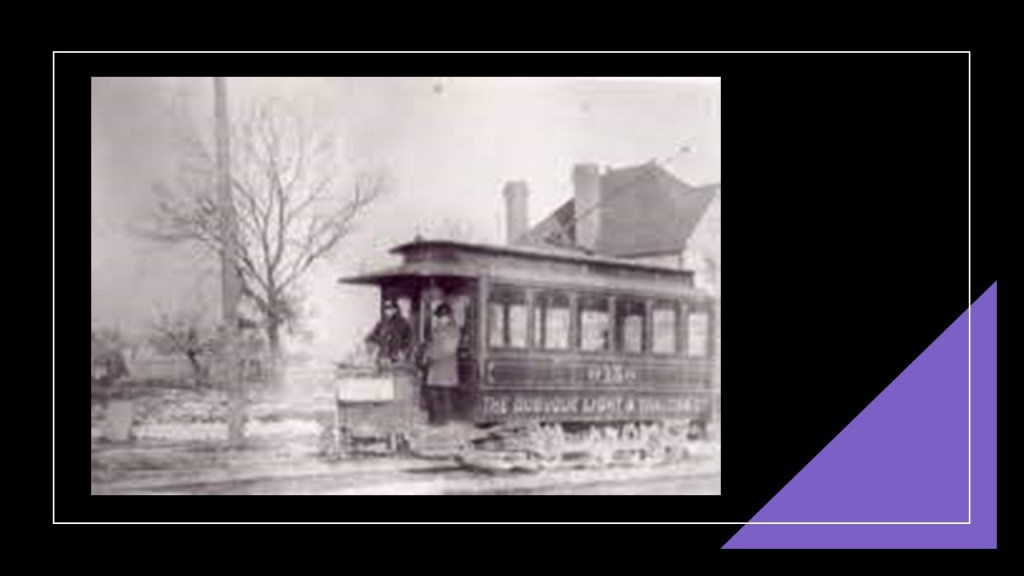

Like Mason City, at one time Dubuque had an electric streetcar system, and which was retired in 1932.

Dubuque still has an operating incline railway.

The Fenelon Place Cable Car is found in Dubuque’s Cathedral Historic District, and is described as the world’s steepest, shortest scenic railway, said to have been built in 1882 for the private-use of J. K. Graves, a local banker and State Senator.

The Dubuque Railroad Bridge is currently operated by the Canadian National Railway, who purchased the Illinois Central Railroad in 1999.

It is a single-track railroad bridge that crosses the Mississippi River between Dubuque Iowa, and East Dubuque, Illinois, that has a swing-span.

The original swing bridge was said to have been built in 1868, and that it was rebuilt in 1898.

Now on to the West Coast, to the last place that I am going to take a look at in northern California, and actually my starting point in this journey of discovery that has taken me in all directions investigating railroads and waterfalls and related infrastructure.

A friend of mine sent me pictures and video of where she was staying in Dunsmuir that got my mind going in this direction and the information she sent was the “A-ha” that pulled all these things together for me in a new way.

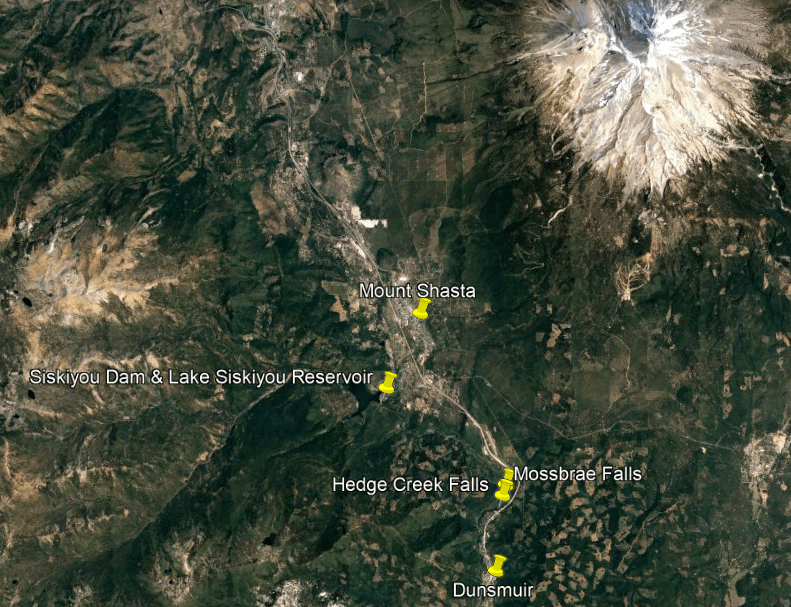

My friend was staying at the Railroad Park Resort in Dunsmuir, at the foot of one of her favorite places, Castle Crags in Siskiyou County near Mount Shasta.

The lodging accommodations consist of 23-renovated cabooses, four cabins, 24 tent campsites…

…and the restaurant is built inside authentic vintage railroad cars.

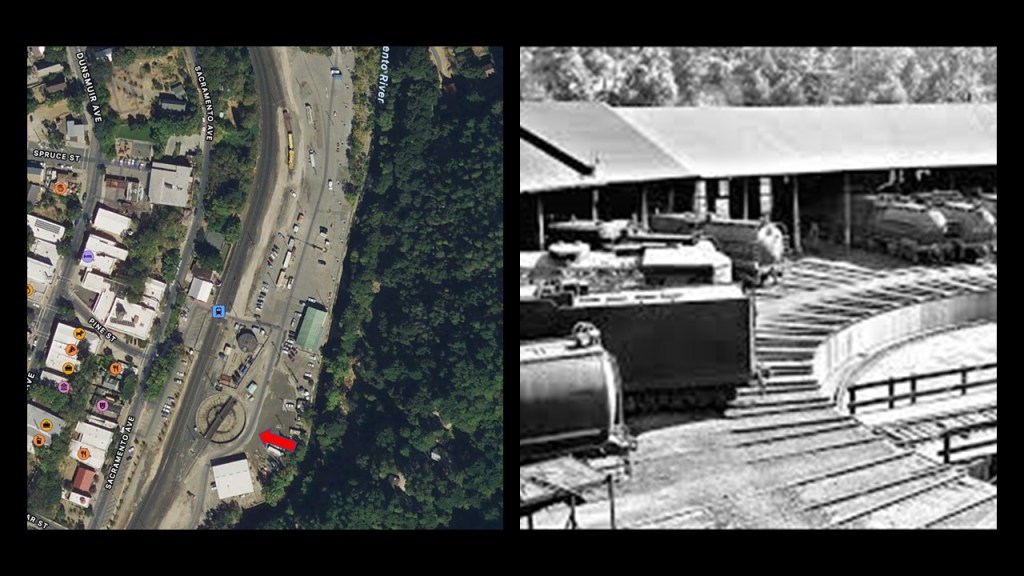

Dunsmuir is a popular tourist destination and important railroad town located on the Upper Sacramento River.

Interstate 5 runs along the Sacramento River Canyon along with the railroad and Upper Sacramento River.

There was an historic roundhouse and turntable here, said to have been built by the Central Pacific Railroad in the 1880s, along with a depot, railyards and machine shops.

By the 1950s, so after only 70-years of existence in the historical narrative, the roundhouse and some of the other rail-related infrastructure was for all intents and purposes torn down.

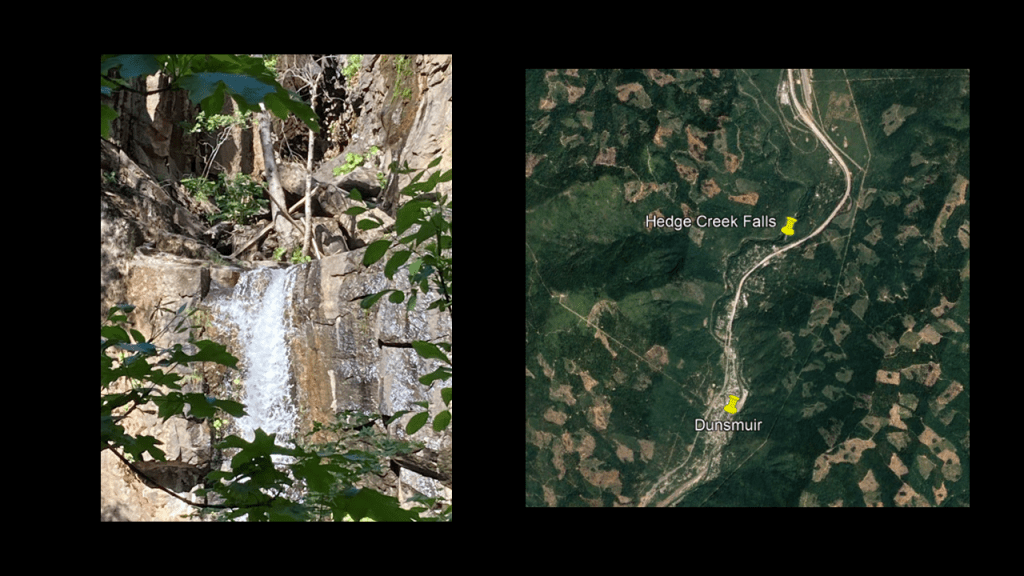

The trip going north from Dunsmuir through the Sacremento River Canyon goes past several waterfalls, and the first one being the Hedge Creek Falls.

The Hedge Creek Falls are a short-walk from I-5 and Dunsmuir Avenue…and the only waterfalls open to the public.

The Mossbrae Falls are next, and not open to the public for the given reasons of 1) They are on Union Pacific Railroad-owned property; and 2) public safety concerns due to the active rail-line that runs alongside the falls.

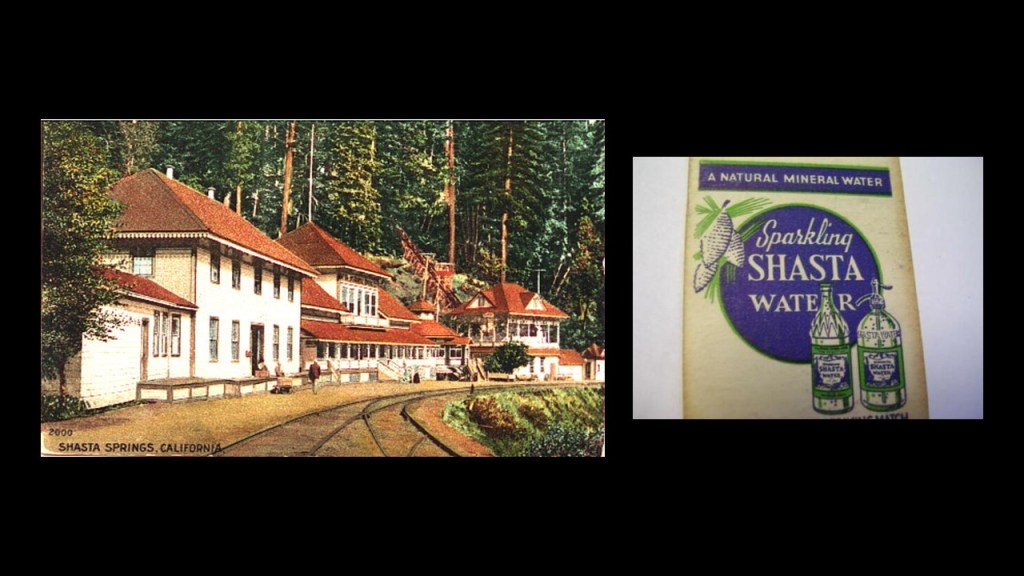

The Mossbrae Falls are just south of the former Shasta Springs Resort, a popular summer resort in the late 19th- and early 20th-centuries, and the springs on the property were the original source of the water and beverages that became known as the Shasta brand of soft-drinks.

The Shasta Springs Resort was sold in the 1950s to the St. Germain Foundation, the current owners of the property and is still in use as use as a major facility by the organization.

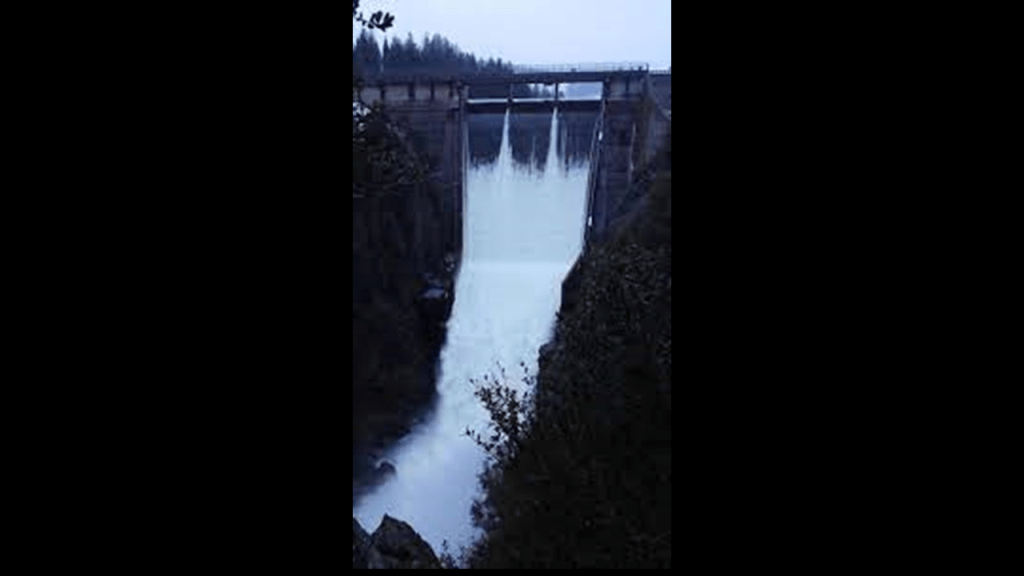

The Siskiyou Dam and Lake Siskiyou Reservoir come next on the way into the city of Mount Shasta.

The Siskiyou Dam, known as the “Box Canyon” Dam, was said to have been completed in 1965 for flood control and a power station installed the same year for hydroelectric power, and that it opened in 1970.

The Lake Siskiyou Reservoir is formed by the Box Canyon Dam, and is 2-miles or 3-kilometers, from Mt. Shasta.

When I see photos of places like this one showing a perfect mirrored reflection of Mount Shasta, I can’t help but wonder if this is an intentional alignment of heaven and earth, and an example of “As above, So below.”

From what I am seeing, the Master Moorish Masons, the builders of the original civilization, were doing exactly that with everything they created.

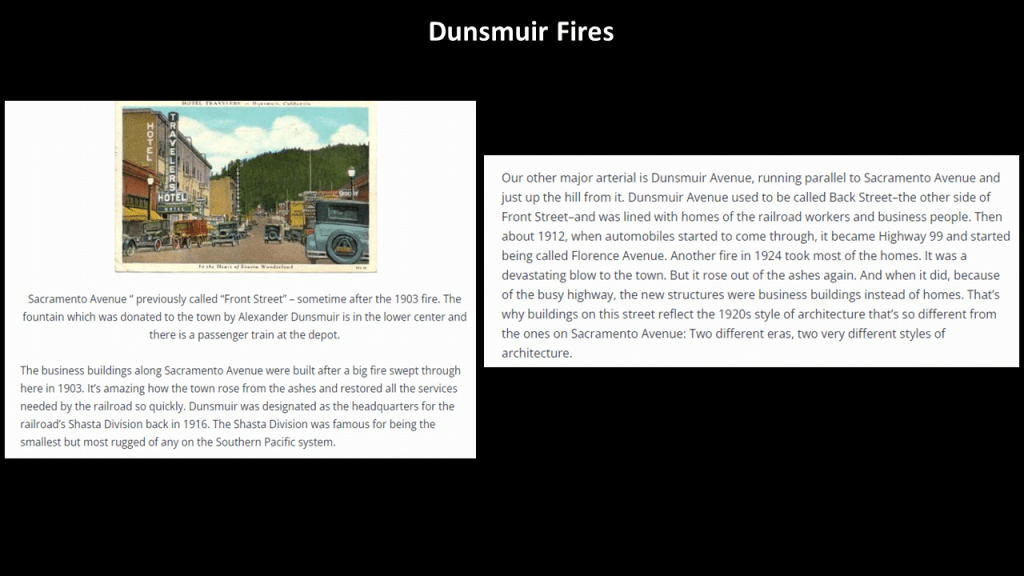

Along with the same kind of infrastructure found at the Tallulah Gorge back in Georgia, Dunsmuir also had a fire problem, with big fires there in both 1903 and 1924.

Bridges in Siskiyou County include:

The Pioneer Bridge and Stone Memorial, said to have been erected in 1931 on Old Highway 99 as a tribute to the stage drivers along this pass in the 1800s.

Until largely replaced by I-5, U. S. Highway 99 was a main North-South United States Numbered Highway on the west coast from 1926 until 1964, running from Calexico, California, on the border with Mexico, to Blaine, Washington, on the Canadian border, and nicknamed among other things “The Main Street of California.”

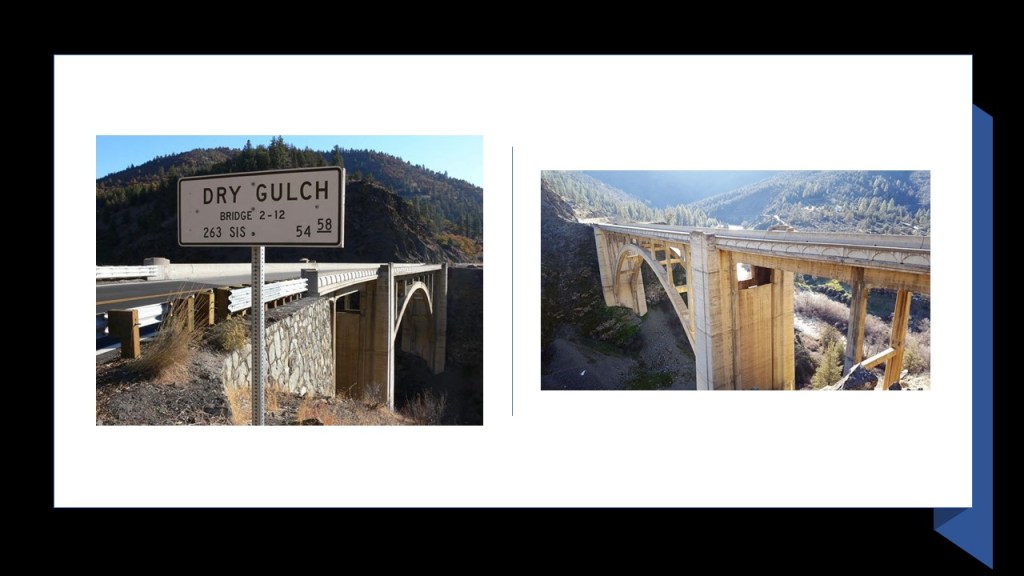

Another historic bridge on Old Highway 99 that is now part of State Road 263 in Siskiyou County is the Dry Gulch Bridge.

I found years of both 1929 and 1930 for the completion of the concrete deck-arch bridge as a realignment and improvement of Old Highway 99 between Yreka to the River Klamath in the Shasta River Canyon.

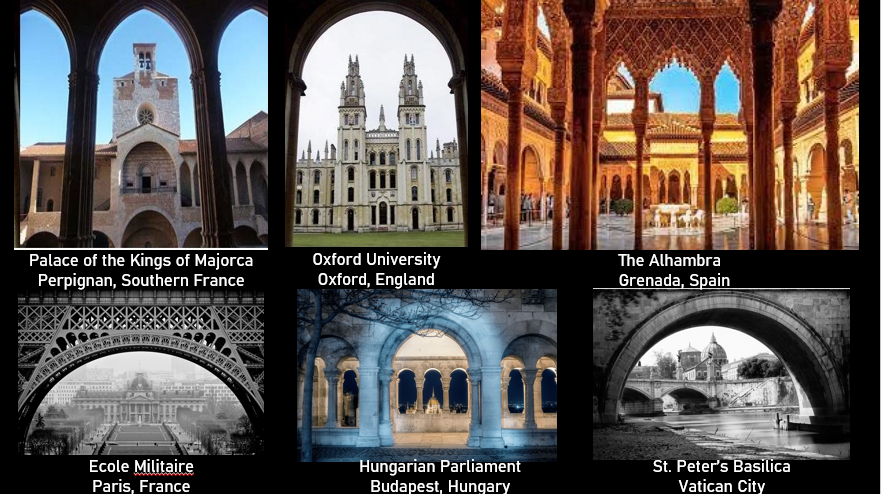

In conclusion, I have provided examples of identical infrastructure and engineering from all across the country.

Railroads and waterfalls in particular are connected to hydroelectric power in gorges and canyons with dams and reservoirs, and the result of sophisticated, impossible-seeming, engineering feats that are totally integrated across vast distances.

How is this even possible according to the history we are taught?

And then, more often than not, this infrastructure was dismantled, abandoned, or destroyed by fire, with an unknown rail history in most places today.

All the railroad junctions I encountered brought to mind “Petticoat Junction” the television sitcom that aired between 1963 and 1970, and I looked it up to see if there might have been disclosure about railroads in the show, where they were telling us something without telling us they were telling us!

Sure enough, the action in the show centers around life at the Shady Rest Hotel, of which many of these original Old World buildings, known to us as Victorian, were converted into…

…and a spur rail line that only connects Hooterville to Pixley because it was cut off from the rest of the railroad 20 years before because a trestle was demolished, and many show plots involved a railroad executive’s attempts to cease operation and scrap the railroad that runs along it.

Sadly telling us the fate of so much railroad infrastructure which has otherwise been hidden from our awareness.

I have a project in mind to fully investigate the lost rail and canal infrastructure of where I live in north-central Arizona, particularly the Verde Valley, but I am really just getting started with it.

I now know where to focus my attention and how to piece it together because of the research in this post

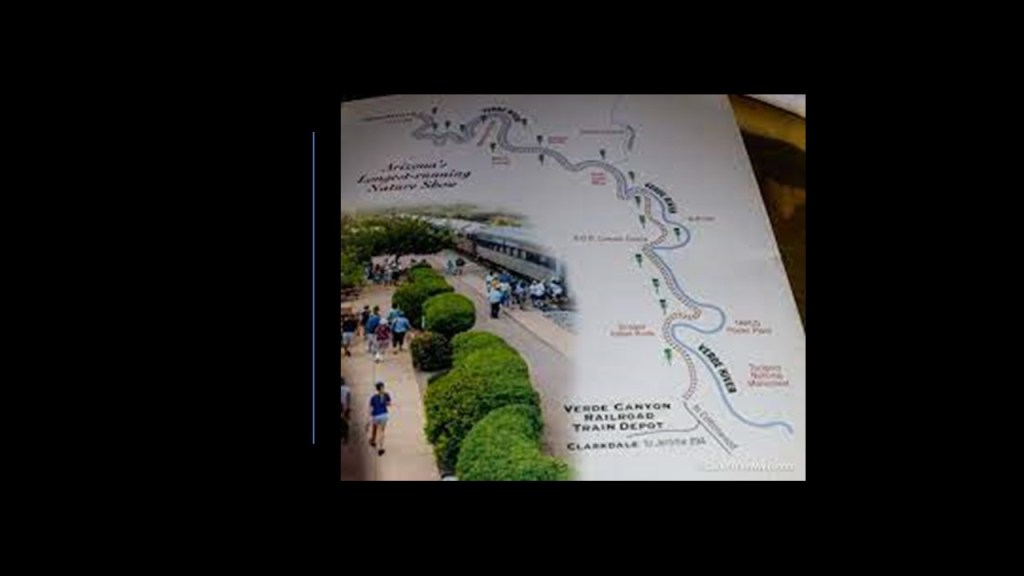

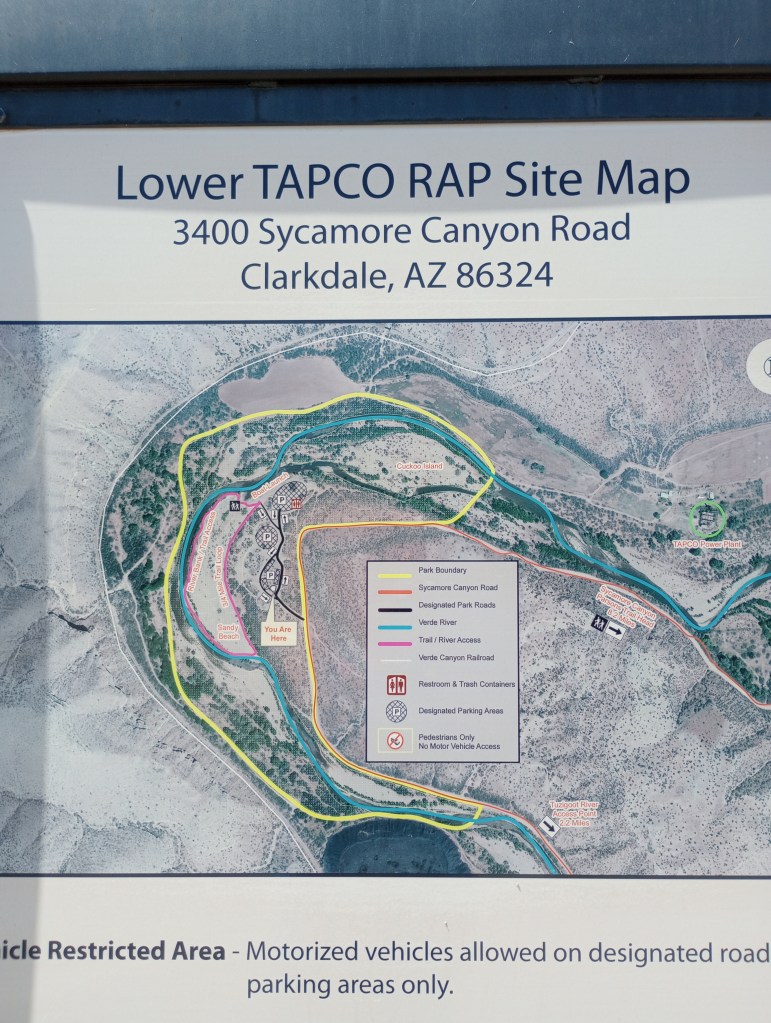

I spent this Memorial Day last week looking at places along the Verde River between Cottonwood and Clarkdale, from where the Verde Canyon Railroad runs a 20-mile, or 32-kilometer, -long trip to Perkinsville as a tourist attraction.

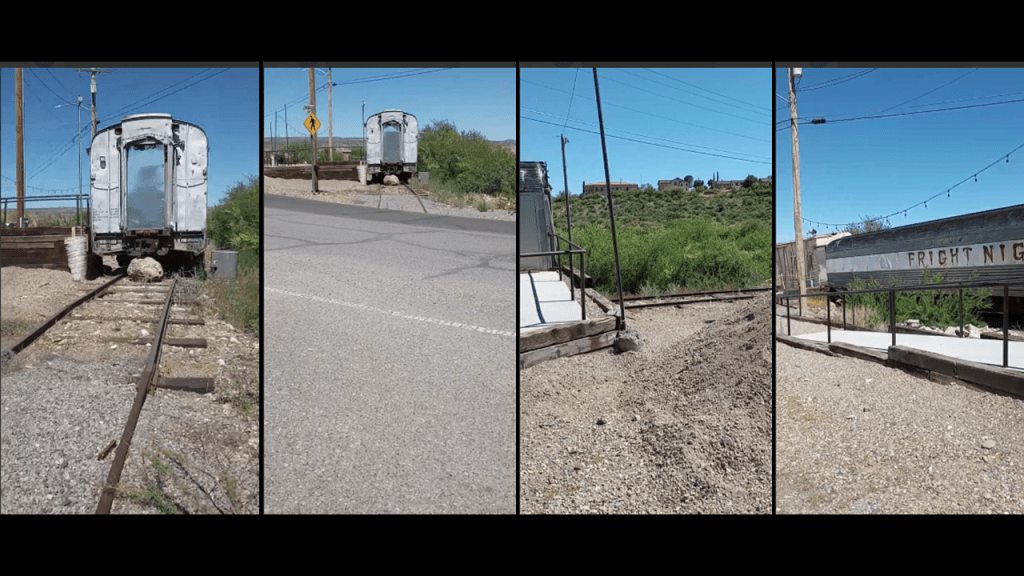

I am bringing this up here and now because I saw an abandoned rail-line and trestle in Clarkdale that branches off from the rail-line used by the Verde Canyon Railroad.

This is the Train Depot and trains used by the tourist attraction.

Facing in the opposite direction, there are some ratty-looking old train cars on an abandoned rail-line in front of the Verde Canyon Railroad Depot in Clarkdale, surrounded by utility poles.

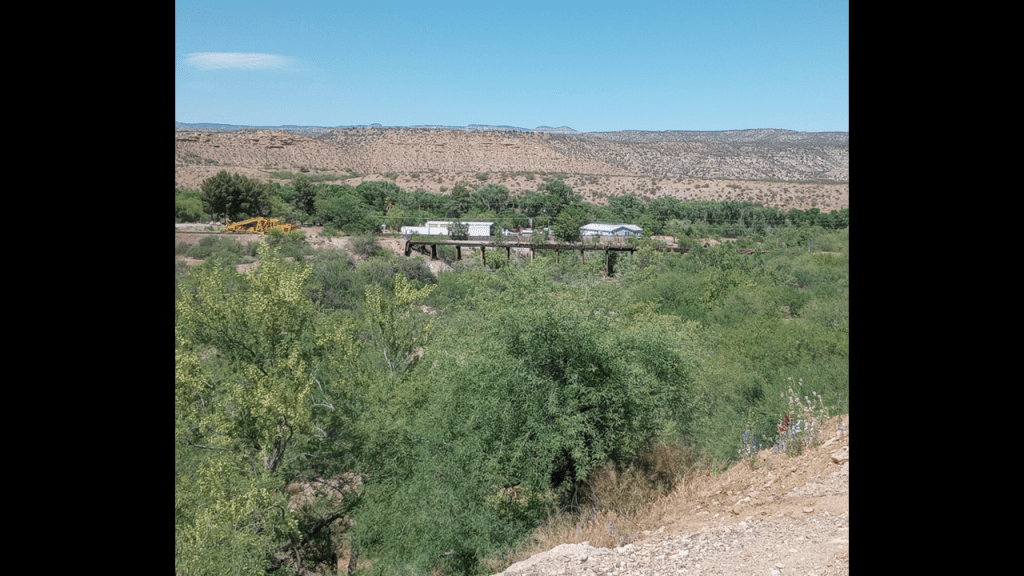

Here’s a view of the train trestle below the train depot in the direction of the where the abandoned train line below the main depot would have gone.

I first spotted the train trestle when I was driving on the other side of this location down towards the “Verde River Access Point TAPCO,” an historic power plant that operated from 1917 to 1958 – apparently in a river bend – in a place called “Sycamore Canyon,” yet another tree reference in a place loaded with tree references.

Not only are there a lot of tree names around here, there was historic copper, gold, and silver mining-related activity in the region in Clarkdale and its neighbor Jerome…

…and there’s even a sign going into Clarkdale displaying two large trees along with the name.

Hmmm!

And the overall appearance of the Verde, meaning “Green,” Valley region definitely does not live up to its name, though there are trees here.

Memories from Mr. Rogers’ Neighborhood popped into my head and the infrastructure of the “Land of Make Believe,” which I would watch on occasion with my younger brothers since I was from the Captain Kangaroo generation of children’s programming.

I now think there were hidden meanings, beyond a clever way to tell a story to young children, behind the sentient Trolley and the infrastructure of the Neighborhood of Make-Believe in this long-running children’s show.

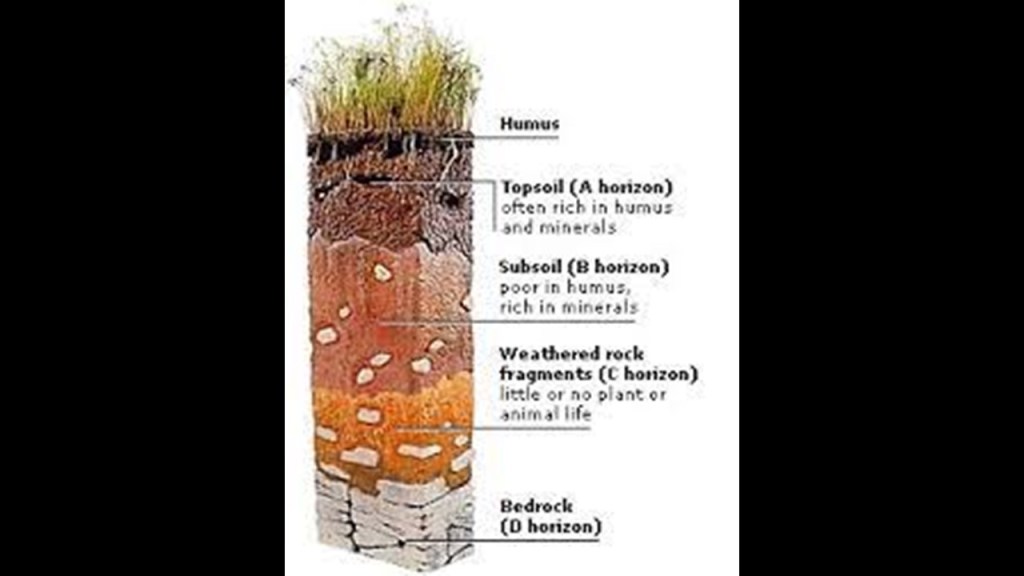

The mention of the Niagara Escarpment as bedrock, a term in geology used to refer to solid rock in the earth’s crust that lies underneath loose material…

…brought to mind the Flintstones and their hometown of Bedrock. The original animated TV show ran for 166 episodes between 1960 and 1966, and was network televisions first animated series.

The graphic of the Flintstones’ Bedrock on the top left brought to mind Cappodocia in Turkey, on the bottom left, and on the bottom right, Holy Land USA, said to be a theme park inspired by passages from the Bible that first opened in 1955, and was closed in 1985.

Just sayin’.

With all the railroads, electric companies and water works, the popular Parker Brothers Game “Monopoly” came to mind, a game about buying and selling properties; developing them; collecting rent; and driving opponents into bankruptcy.

The game is named after the economic concept of a monopoly, in which a single entity dominates a market.

That certainly sounds familiar!

Two more things I would like to leave you with in closing.

One is this bridge with what appears to be a solar alignment and a lot of interesting effects going on as well in the photo.

The other is this spoof from the children’s Electric Company program from the 1970s on “2001: A Space Odyssey” for contemplation about whether or not this was just a fun and creative way to teach kids past-tense verb conjugation…or disclosure about a great civilization that once existed in our past.

10 thoughts on “Of Railroads and Waterfalls and Other Physical Infrastructure of the Earth’s Grid System”