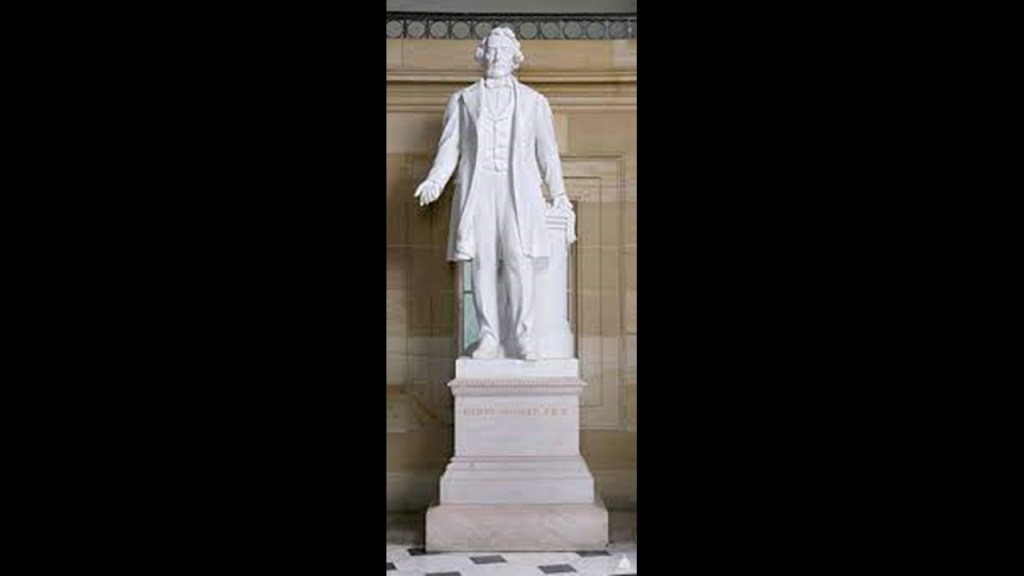

I am currently about half-way through the 50-states of looking at who is represented for each state in the National Statuary Hall at the U. S. Capitol Building in Washington, DC.

There are two statues representing each state.

I am bringing forward unlikely pairs of historical figures represented in the Statuary Hall who have things in common with each other in this separate series called “Snapshots from the National Statuary Hall,” as a way to highlight what I am finding out in the process of doing this research.

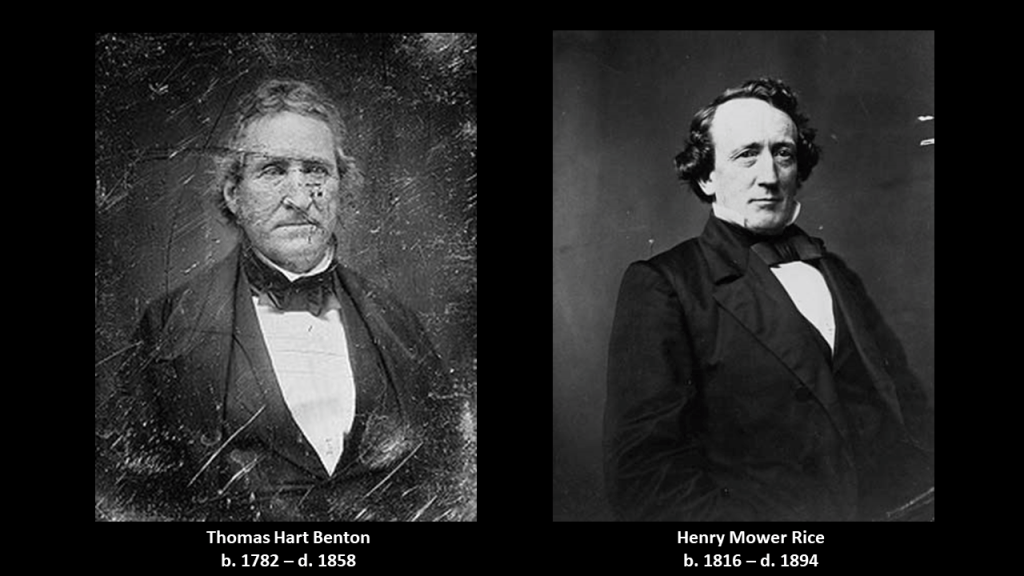

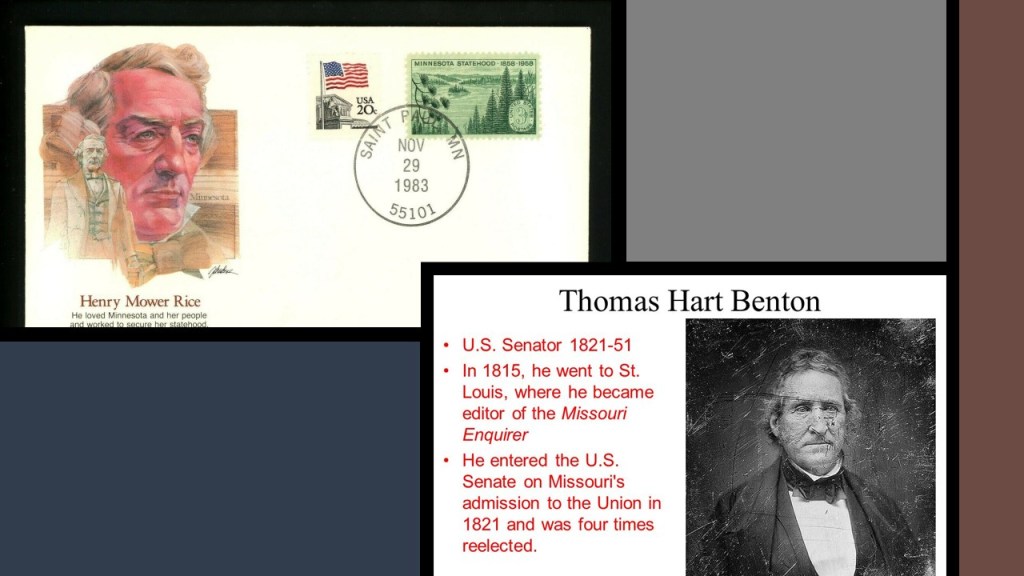

In this “Snapshot,” I am pairing Missouri’s Thomas Hart Benton and Minnesota’s Henry Mower Rice.

I have paired people like Michigan’s Gerald Ford,with Mississippi’s Jefferson Davis; Iowa’s Dr. Norman Borlaug, Ph.D, with Colorado’s Dr. Florence R. Sabin, M.D; and Louisiana’s controversial Governor, Huey P. Long, with Alabama’s Helen Keller; and Kentucky’s Henry Clay with Michigan’s Lewis Cass, among others.

Not only am I finding much in common between the pairs featured in each installment of the “Snaptshots from the Statuary Hall” series, I am finding, regardless of fame or obscurity, that the National Statuary Hall functions more-or-less as a “Who’s Who” for the New World Order and its Agenda.

Thomas Hart Benton was a United States Senator from Missouri, and he was a champion of westward expansion, a cause that became known as “Manifest Destiny.”

He served in the U. S. Senate between 1821 and 1851, becoming the first Senator to serve five-terms.

Thomas Hart Benton was born in March of 1782 near the town of Hillsborough, the county seat Orange County in North Carolina.

His father Jesse was a wealthy landowner and lawyer, and he passed away in 1790.

Apparently Thomas Hart Benton studied law at the University of North Carolina, but was expelled in 1799 for stealing money from other students, after which he managed the family estate for awhile.

The young Benton and his family moved west to a 40,000-acre, or 160-km-squared, holding near Nashville, Tennessee, upon which he was said to have established a plantation with schools, churches, and mills.

It was said that his experience as a pioneer during this time gave him a devotion to Jeffersonian Democracy during his political career.

Benton resumed studying law and was admitted to the Tennessee Bar in 1805, and became a state senator in 1809.

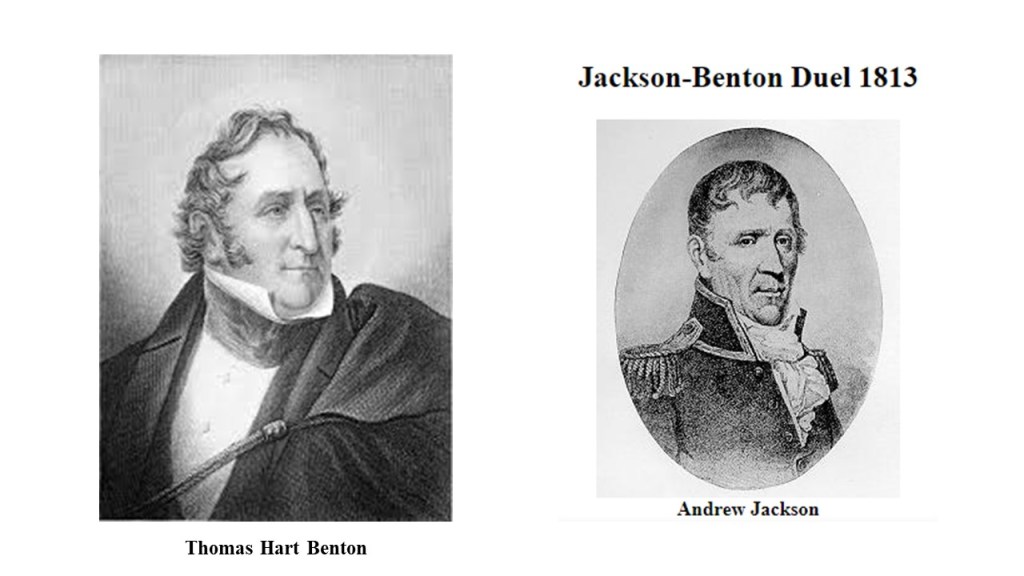

He caught Andrew Jackson’s eye, Tennessee’s First Citizen, and Jackson made Benton his personal assistant with a commission as a Lieutenant Colonel at the outbreak of the War of 1812.

He was assigned to represent Jackson’s military interests in Washington, DC.

But this relationship turned sour somewhere along the way, and in September of 1813, Thomas Hart Benton and his brother Jesse engaged in duel with Jackson in the City Hotel in Nashville, where Jackson was seriously wounded by a gunshot wound in the shoulder.

In 1815, Benton moved to St. Louis, Missouri, where he practiced law and established and became editor of the Missouri Enquirer, the second major newspaper west of the Mississippi River.

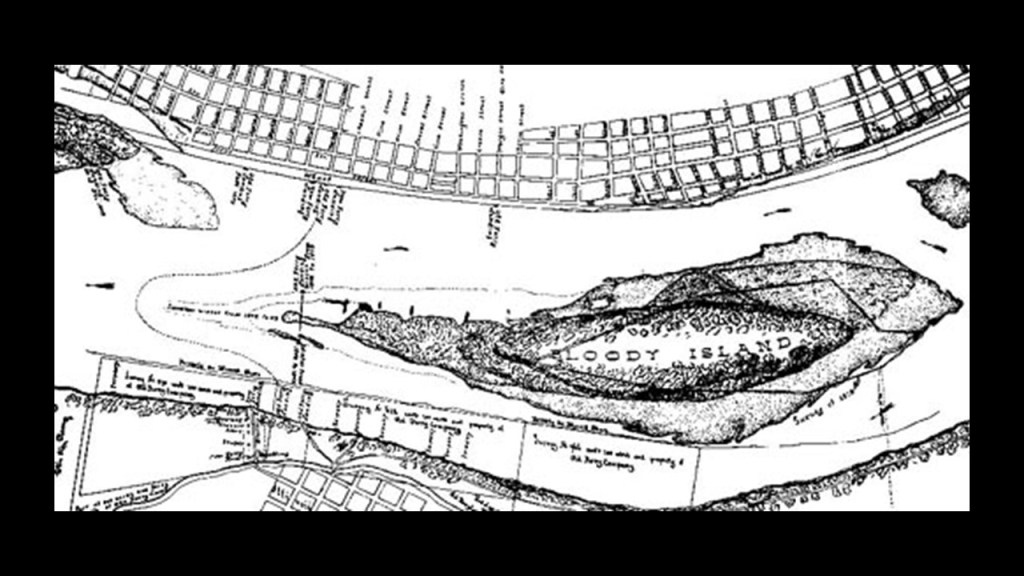

Then, in 1817, Benton and another attorney, Charles Lucas, got cross-wise with each other initially during a court case in which they were opposing each other, and the resulting animosity led to Benton killing Lucas in a duel on a place called “Bloody Island,” a neutral little island in the Mississippi River between Missouri and Illinois where duellists would go because it was not under the control of either state.

We are told that Bloody Island first appeared above-water in 1798, and posed a problem to the St. Louis Harbor.

Then in 1837, Capt. Robert E. Lee, who was then a part of the Army Corps of Engineers, established a system of dikes and dams that washed out the channel and joined the island to the Illinois shore.

The Miami people of the Great Lakes Region stopped on Bloody Island when they were being forcibly removed from their homelands in 1846, where their oral history relates they buried an elder and an infant somewhere in the vicinity.

Interesting to note that the south end of Bloody Island is located at the site of a train-yard.

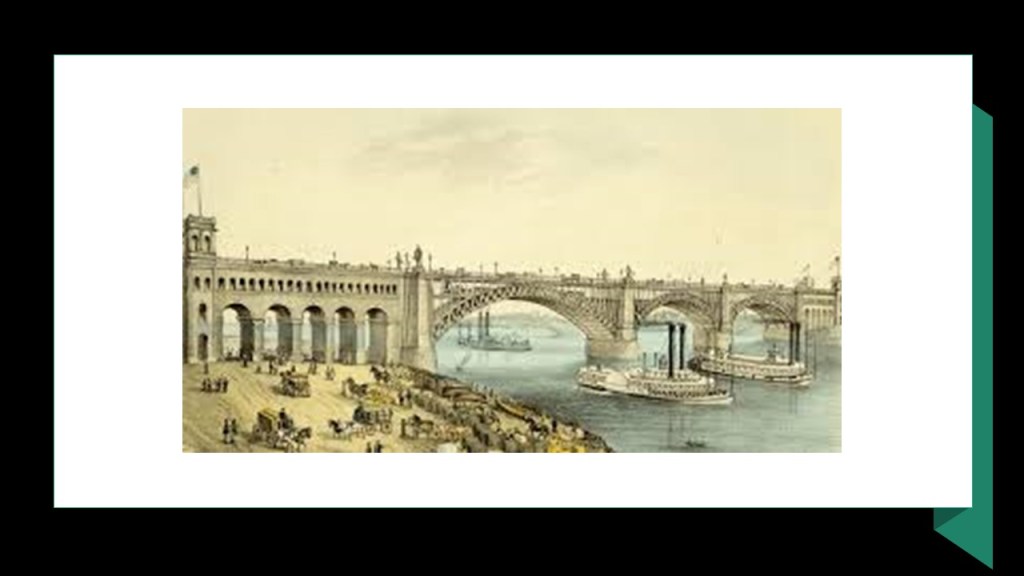

We are told that there was a ferry service that had been developed that operated between East St. Louis and St. Louis starting in the early 1800s that eventually developed the train-yards in the 1870s that carted train cars across the Mississippi River, using an 8-horse-team to power the propulsion, until the Eads Bridge, a combined road-and-railway-bridge opened in 1874, which is located between LaClede’s Landing on the northside, and the grounds of the Gateway Arch on the southside.

Construction of the bridge was said to have started in 1867 (two-years after the end of the American Civil War) and completed in 1874.

Bloody Island was once the site of a huge network of railroad tracks, but with the exception of a few rail-lines in use, the area has largely returned to nature.

And this location is in close proximity not only to the Gateway Arch, but to the Busch Stadium as well, home of the St. Louis Cardinals Major League Baseball team.

Hmmm…I wonder what they are not telling us about our true history and about this place!

When the Missouri Compromise of 1820 resulted in the Missouri Territory becoming a state, Benton was elected as one of its first U. S. Senators.

The Missouri Compromise was federal legislation that balanced the desires of northern states to prevent the expansion of slavery in the country, with those of southern states seeking to expand it.

It admitted Missouri as a slave state, and Maine as a free state, and prohibited slavery in the remaining Louisiana Purchase lands north of the 36.5-degree parallel.

Andrew Jackson was one of four candidates for President, along with Henry Clay and William H. Crawford, in the 1824 Election, with John Quincy Adams ultimately winning the election without a majority of the electoral or popular vote.

Andrew Jackson again ran for the Presidency in 1828, running against sitting-President John Quincy Adams, and this time he was successful, and ended-up serving two presidential terms.

Apparently Thomas Hart Benton and Andrew Jackson set aside their differences and joined forces over the issue of money and banking.

Benton, nicknamed “Old Bullion,” was in favor of “hard money,” like gold coins and/or bullion.

Jackson and Benton were both against the Second Bank of the United States, which was a federally-authorized national bank in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, from when it was chartered in 1816.

It was a private bank with public duties, handling all fiscal transactions for the U. S. Government, accountable to Congress and the Treasury Department.

Four-thousand private investors held 80% of the bank’s capital, of which three-thousand of those investors were European, with a bulk of the stocks held by a few hundred wealthy Americans.

Kinda sounds familiar….

The “Bank War” started in 1832 during the Jackson Presidency, and was a political struggle that occurred over the issue of rechartering the bank, and a conflict that involved the Federal Government over the State Sovereignty in the U. S. political system.

The Second Bank of the United States had the exclusive right to conduct banking on a national scale, with the vision of stabilizing the economy, providing a uniform currency, and strengthening the federal government.

Jackson and Jacksonian Democrats saw the public-private organization of Second Bank as favoring merchants and speculators over the rest of society, and as unconstitutional, with the bank’s charter violating state sovereignty.

In 1832, President Jackson vetoed the bill Congress had passed to reauthorize the Second Bank’s charter, and quickly removed federal deposits from the bank, arranging for their distribution to state banks in 1833.

President Jackson was censured by the Senate in 1834 for cancelling the Second Bank’s Charter, for which Benton successfully led the campaign to remove Jackson’s censure from the official record in 1837.

The Second Bank never secured its recharter, and it was liquidated in 1841.

President Jackson issued an executive order in 1836 known as the “Specie Circular,” which required payment for government land to be made in gold and silver, and a reaction to concerns about excessive speculation of land that took place after the implementation of the 1830 Indian Removal Act, which also took place during President Jackson’s Administration as mentioned previously in this post.

Many at the time, and later historians, blamed the “Specie Circular” for the Panic of 1837, a financial crisis which touched off a major depression lasting until the mid-1840s, where wages, prices and profits went down, unemployment went up, and westward expansion was stalled.

We are told that by 1850, the economy was booming again because of the increased specie flows from the California Gold Rush.

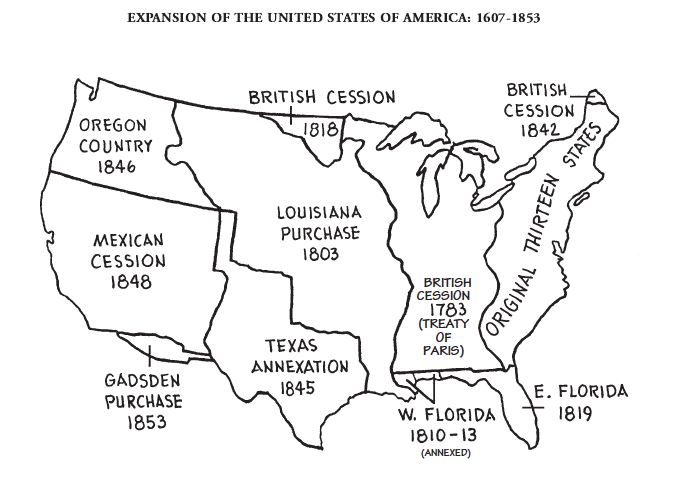

As Senator, Benton’s main concern was westward expansion, or what became known as “Manifest Destiny,” a 19th-century belief that the United States was destined by God to expand its dominion and spread democracy and capitalism across the entire continent.

Benton was the major reason for the sole administration of the Oregon Territory, which had been jointly-occupied by the United States and Great Britain since the Anglo-American Convention of 1818.

Benton chose the current 49th-parallel border Between the U. S. and Canada set by the Oregon Treaty in 1846.

Benton pushed for more exploration of the West, including support for the numerous treks of his son-in-law, explorer and cartographer John C. Fremont…

…to get public support for the transcontinental railroad…

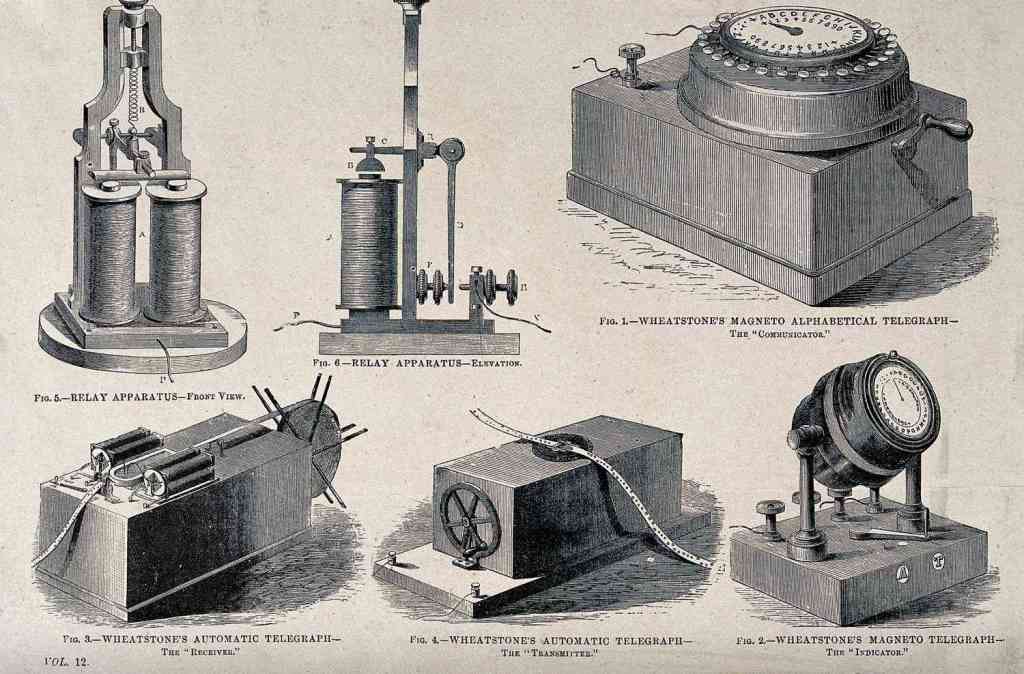

…and for greater use of the telegraph for long-distance communication.

Benton was the Legislative right-hand man for President Andrew Jackson, as well as the next President, Martin van Buren.

His power and influence started to diminish when James Polk became President in 1845, and by 1851, he was denied a sixth-term in the Senate by the Missouri legislature.

The last office he held was in the U. S. House of Representatives for two years, between 1852 and 1854, and he lost elections for both a second term in the House as well as for Governor of Missouri in 1856.

Benton died in April 1858 in Washington, DC, and he was buried in the Bellefontaine Cemetery in St. Louis.

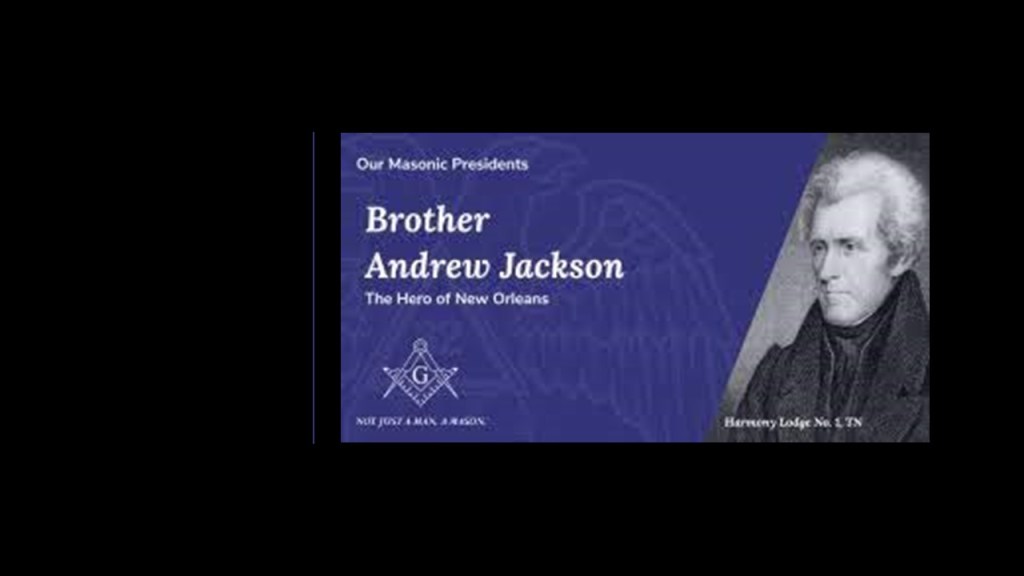

And was Thomas Benton Hart a Freemason too?

This certainly appears to be the case….

For that matter, Andrew Jackson was too!

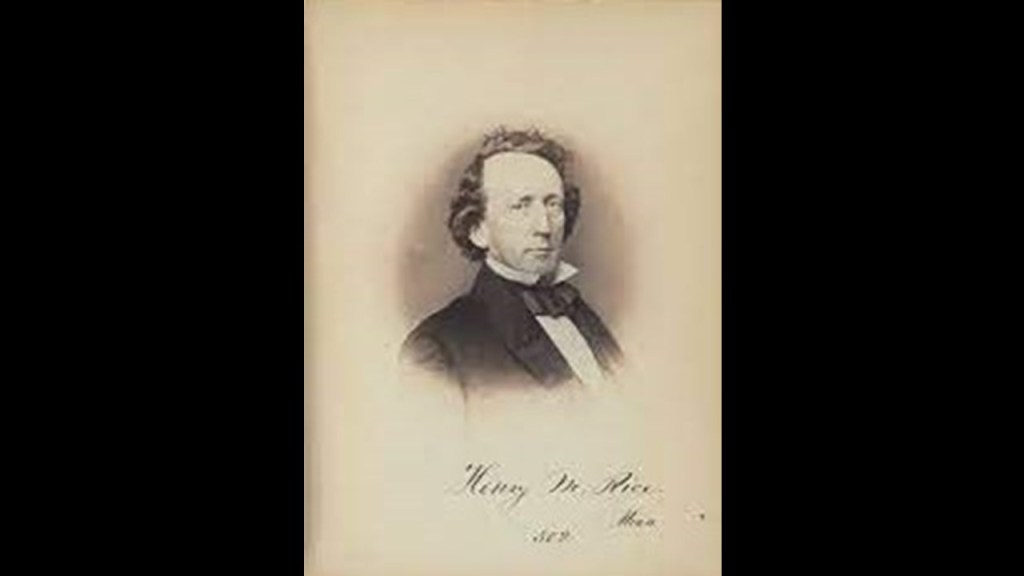

Henry Mower Rice was a fur trader and prominent Minnesota politician involved in Minnesota becoming a state.

Henry Mower Rice was born in Waitsfield, Vermont, on November 29th of 1816, to parents of English ancestry in New England since the 1600s.

His father died when he was young, so he lived with family friends when growing up.

The town of Waitsfield was established by charter in February of 1782, and granted to Revolutionary War Militia Generals Benjamin Wait, Roger Enos, and others.

Rice moved to Detroit, Michigan, when he was 18, and he participated in surveying the canal route around the rapids of Sault Ste. Marie between Lake Superior and Lake Huron.

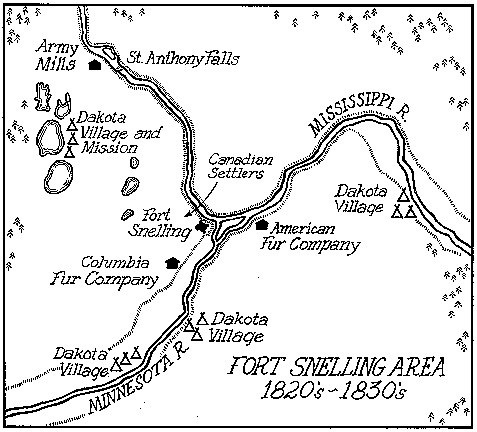

Then in 1839, Rice got a job at Fort Snelling, near Minneapolis, Minnesota, and became a fur trader with the Ojibwe and Winnebago people in the area.

Rice attained a position of trust and influence with them, and he was instrumental in negotiating the 1847 Treaty of Fond du Lac with the Ojibwe, in which they ceded extensive lands to the United States.

Historic Fort Snelling was said to have been constructed in the 1820s.

The Fort served as the main center for U. S. Government forces during the Dakota War of 1862, also known as the Sioux Uprising, an armed conflict between the United States and several tribes of the Eastern Dakota known as the Santee Sioux.

Today what is called the Unorganized Territory of Fort Snelling includes not only the historic fort, but the Coldwater Spring Park, Minneapolis-Saint Paul International Airport, parts of the Mississippi National River and Recreation Area, a National Guard base, a National Cemetery, the Minneapolis VA Medical Center, and several other state government facilities as well.

Rice lobbied for the bill to establish the Minnesota Territory in 1849, and went on to serve as its delegate in the U. S. Congress between March 4th of 1853 and March 4th of 1857.

He facilitated Minnesota becoming a state in 1858 by his work on the Minnesota Enabling Act, which passed Congress in February of 1857.

When Minnesota became a state, Henry Mower Rice and James Shields were elected by the Minnesota Legislature as Democrats to the United States Senate, and Rice served in this capacity from May 11th of 1858 to March 4th of 1863.

The other Minnesota Senator who served with Henry Mower Rice as the State of Minnesota’s first U. S. Senators, James Shields, represents the State of Illinois in the National Statuary Hall.

He was an Irish-American Democratic politician and U. S. Army officer, and the only person in U. S. history to serve as Senator for three different states, and one of only two to represent more than one state.

He represented Illinois from 1849 to 1855; Minnesota from 1858 to 1859; and Missouri in 1879.

In addition to the 1847 Treaty of Fond du Lac with the Ojibwe, Henry Mower Rice was involved in a number of treaties, including the 1846 Winnebago Treaty ratified in Washington, DC.

Originally native to Wisconsin, the Winnebago had been moved to a reservation in northeastern Iowa as a result of Treaties signed in 1832 and 1837 to a reservation in northeastern Iowa called “neutral ground,” an area considered to be a buffer between other native americans.

The Winnebago were unhappy with American settlers who were encroaching on their reservation land in Iowa, and asked to be moved, hence the 1846 Treaty.

So in exchange for their reservation land in the Iowa Territory for land in the Minnesota Territory, they were offered reservation land in Long Prairie, Minnesota.

Long story short, the Winnebago were shuffled around a lot, and Henry Mower Rice was involved in this whole process, both as a negotiator and in 1850 received a contract from the federal government to remove any Winnebago who had not moved to their reservation land in Long Prairie, Minnesota, in which he was paid per person to bring the unaccounted for Winnebago people to the reservation.

Rice was also involved in the 1854 Treaty of LaPointe, Wisconsin, where the Lake Superior Ojibwe ceded all of their land in the Arrowhead Region of northeastern Minnesota in exchange for reservations in Michigan and Minnesota.

All that is said of Henry Mower Rice’s death is that he died in 1894 during a visit to San Antonio, Texas, and was buried in the Oakland Cemetery in St. Paul, Minnesota.

I am bringing forward unlikely pairs of historical figures who are represented in the National Statuary Hall who have things in common with each other, as mentioned at the beginning of this post.

Both of these men were contemporaries and involved in shaping the future United States during their lifetimes.

Both men served as one of the first Senators of their respective states, with Thomas Hart Benton becoming one of the first Senators of Missouri in 1821 after Missouri became a State with the 1820 Missouri Compromise, and Henry Mower Rice becoming one of the first Senators of Minnesota in 1858 after the Minnesota Enabling Act he had worked on passed Congress in 1857.

And while I couldn’t find a direct confirmation that Henry Mower Rice was a Freemason, like I did for Thomas Hart Benton, I did find this photo of Rice on the left with his right-hand tucked into his coat, which is a recognizeable masonic sign of the “Hidden Hand,” signifying “Master of the Second Veil.”

These two men fall into the category of obscure key players in the historical narrative in shaping and forming what became the United States.

I had never had heard of either man prior to looking into the National Statuary Hall.

I keep finding these obscure historical figures like these two represented here, whose lives and times tell a different kind of story than what we normally hear about.

Really have to wonder about why they were chosen to be so-honored, given things like Benton’s history of duels and Rice’s direct personal involvement in the removal of indigenous people from their traditional lands.

As always, more questions than answers!