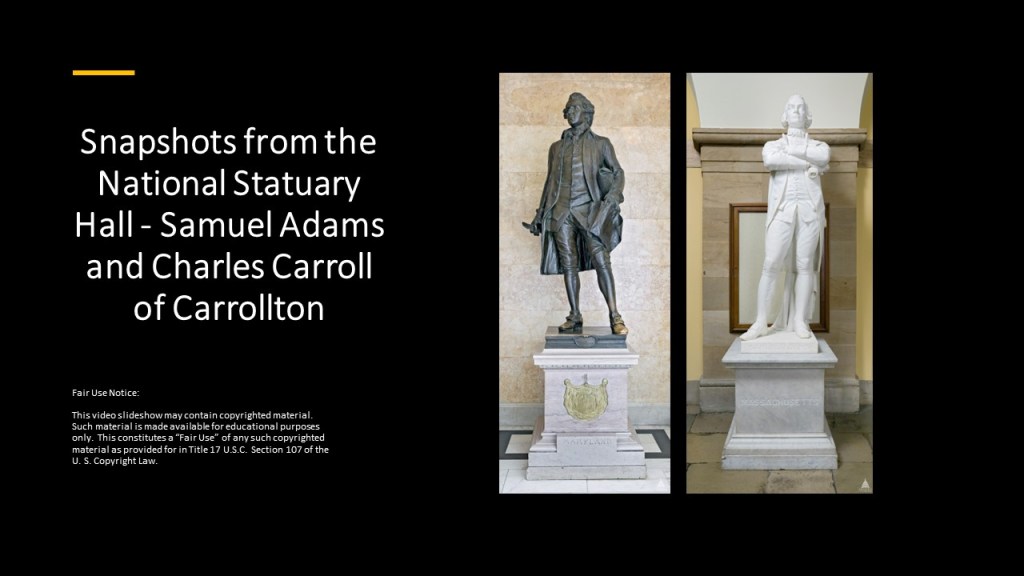

In this series called “Snapshots from the National Statuary Hall,” I am bringing forward unlikely pairs of historical figures represented in the National Statuary Hall at the U. S. Capitol who have things in common with each other .

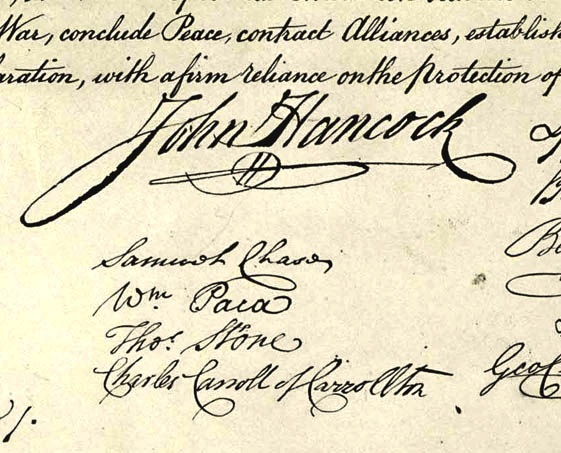

In this post, I am pairing Samuel Adams, who is in the National Statuary Hall for Massachusetts, who was an American statesman, politician, Founding Father of the United States, and Charles Carroll of Carrollton, who represents the State of Maryland, and was an Irish-American politician, planter, the only Catholic signer of the Declaration of Independence, and also considered a Founding Father.

So far in this series, I have paired Michigan’s Gerald Ford, a former President of the United States, and Mississippi’s Jefferson Davis, the former President of the Confederate States of America, and both men featured on the cover of the “Knight Templar” Magazine,; Dr. Norman Borlaug, Ph.D, often called the “Father of the Green Revolution; and Colorado’s Dr. Florence R. Sabin, M.D, a pioneer for women in science, both of whom worked for the Rockefeller Foundations; Louisiana’s controversial Socialist Governor, Huey P. Long, and Alabama’s Helen Keller, a deaf-blind woman who gained prominence as an author, lecturer, Socialist activist; Henry Clay, attorney, plantation owner, and statesman from Kentucky, and Lewis Cass, a military officer who was directly behind Native American Removals, politician and statesman from Michigan, contemporaries who were both Freemasons and unsuccessful candidates for U. S. President.; John Gorrie for Florida, a physician and inventor of mechanical refrigeration and William King for Maine, a merchant and Maine’s first governor, both Freemasons; and Dwight D. Eisenhower, Supreme Commander of the Allied Expeditionary Force in Europe during World War II and former President representing the State of Kansas, and Lew Wallace, Union General and former Governor of New Mexico Territory, representing the State of Indiana, both of whom were involved in the entirety of their major wars, and in the events concerning crimes in the aftermath of their wars; and Francis Preston Blair, Jr, representing Missouri, and Edmund Kirby Smith for Florida, both major players in events of the Mexican-American War and the American Civil War; and John Winthrop, a leader in establishing the Massachusetts Bay Colony in 1630, with St. Junipero Serra, a notorious Franciscan missionary and Roman Catholic priest who established early missions in California.

First, Samuel Adams.

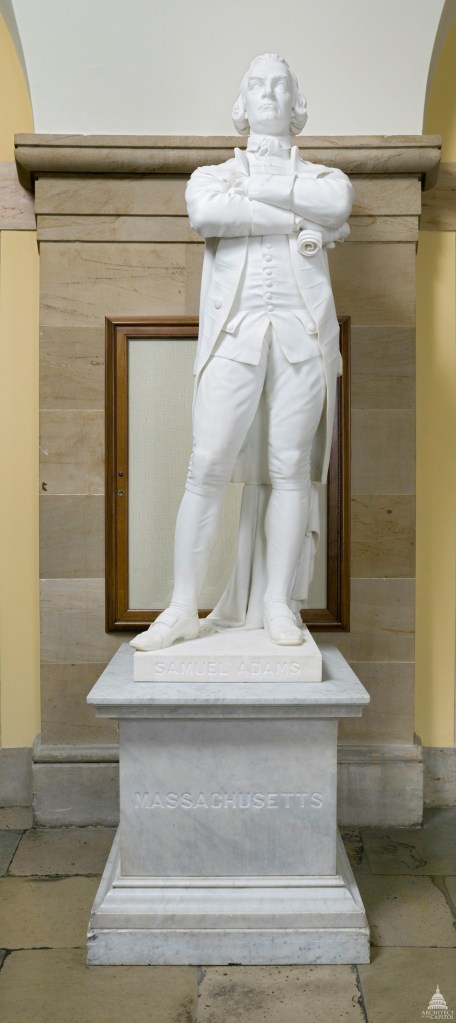

Samuel Adams represents the State of Massachusetts in the National Statuary Hall.

Samuel Adams was an American statesman, politician, Founding Father of the United States, and one of the architects of the principles of American Republicanism that shaped the political culture of the United States.

Samuel Adams was born in Boston in the British Colony of Massachusetts in September of 1722, one of three children who survived out of 12 born to his parents, brewer Samuel Adams Sr. and Mary Fifield Adams.

They were Puritans, and members of the Old South Congregational Church, which is famous as the place where the Boston Tea Party was organized.

This is a photo of the original Old South Meeting House circa 1900…

…which still stands today at the corner of Milk and Washington Streets in Boston’s Downtown Crossing area.

We are told that the present building of the Old South Congregational Church was completed in 1873 after the Old South Meeting House was almost destroyed in the Great Boston Fire of 1872.

Is it just me, or does the Old South Church’s cornerstone look a little strange?

It looks plastered over, and is not the same material as the stone surrounding it.

And the “16” of the “1670” date sure looks like it was worked with more than once.

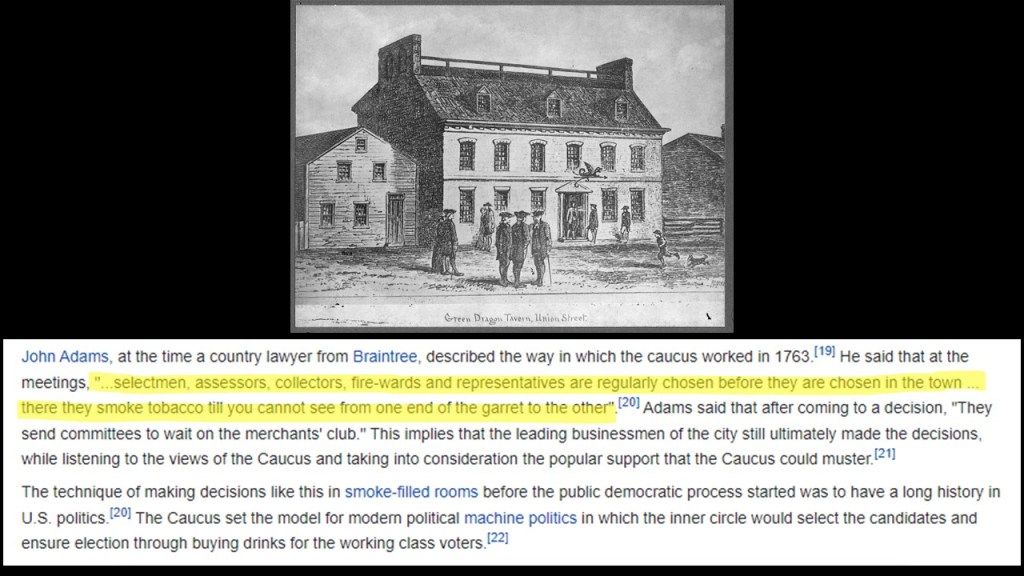

The elder Samuel Adams, a Deacon of the church, entered politics through an informal political organization known to history as the “Boston Caucus,” which he was one of the founders of.

The “Boston Caucus” promoted candidates who supported popular causes in the years before and after the American Revolution, typically meeting in the smoke-filled rooms of taverns or pubs.

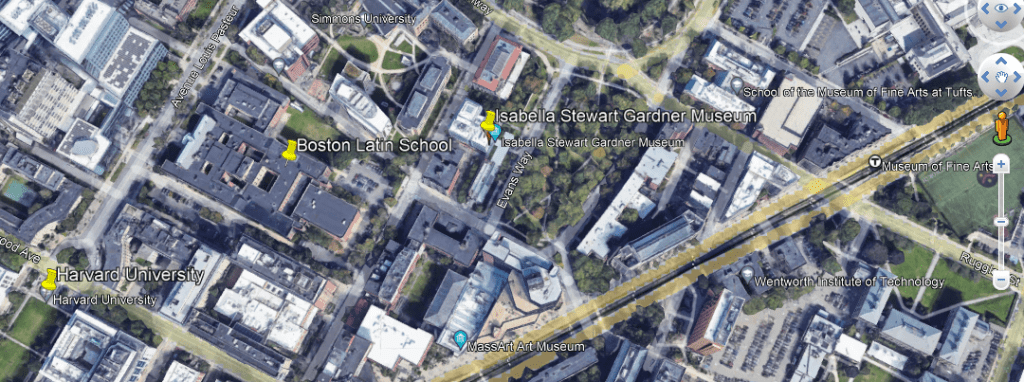

The younger Samuel Adams attended the Boston Latin School, which was established in 1635, and the oldest public school in British America and the oldest existing school in the United States.

Adams entered Harvard College in 1736 and graduated in 1740.

He continued in his studies, earning a Master’s Degree in 1743.

He was particularly interested in politics and colonial rights.

Founded in 1636, Harvard College, the original school of Harvard University, is the oldest institution of higher learning in the United States.

Harvard University is located right across the street from the Boston Latin School, and among many other universities and museums, the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum is only a short-walking-distance from the Boston Latin School.

The largest art theft in U. S. history took place on March 18th of 1990, at which time twelve paintings and a Chinese Shang Dynasty vase, all together worth $100 to $300 million, were stolen from Boston’s Isabella Stewart Gardner Art Museum.

There is still a $10 million reward in place today for information leading to the recovery of the art work.

The museum was said to have been built between 1898 and 1901, with the design heavily influenced by art-collector and philanthropist Isabella Stewart Gardner herself on the left, in the style of a 15th-century Venetian Palace, of which the 15th-century Palazzo Santa Sofia in Venice on the right is an example of this type of architecture.

The art museum is located near the Back Bay Fens, one of the areas of Boston that was reclaimed between 1820 and 1900, and said to have been designed by Frederick Law Olmsted as part of Boston’s Emerald Necklace system of parks.

Back to Samuel Adams.

Adams considered going into law after leaving Harvard in 1743, but ended up going into business, working at a counting house until he was let go after a few months because he was too preoccupied with politics.

His father subsequently made him a partner in the family’s malthouse, where the malt necessary for brewing beer was produced.

He was first elected into political office in 1747 as one of the clerks of the Boston Market, and in 1756, he was elected to the position of Tax Collector by the Boston Town Meeting.

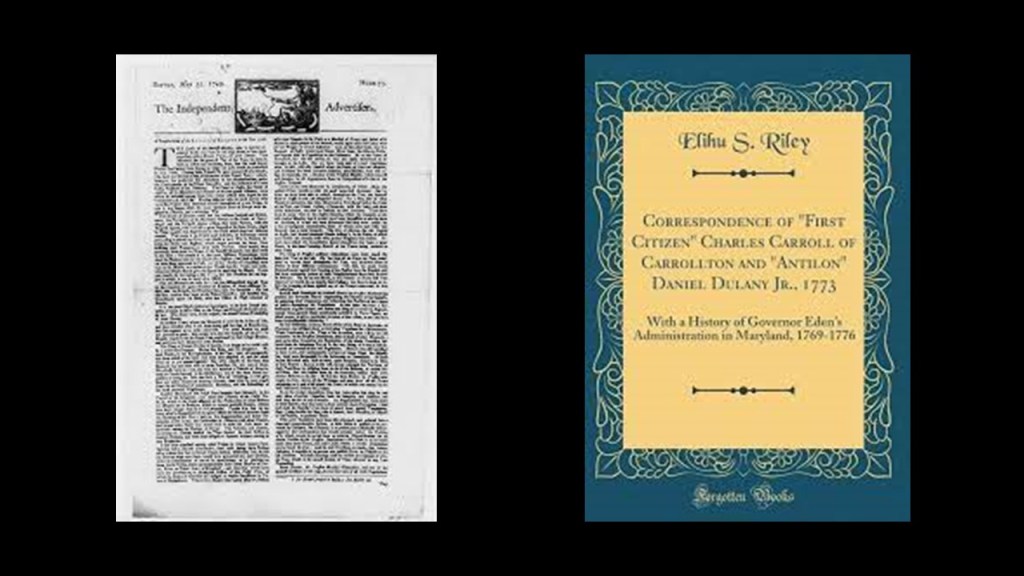

In January of 1748, Samuel Adams and some friends launched “The Independent Advertiser,” which advocated republicanism, liberty and independence from Great Britain, after he and his friends became inflamed by British impressment, where men were forcibly taken into military or naval service.

He went into what can best be described as full-on political activism against Great Britain.

The 1764 Sugar Act passed by the British Parliament was a revenue-raising act for goods which could only be exported to Britain.

It was protested in the colonies for its economic impact, as well as the issue of taxation without representation, by merchants boycotting British goods and Samuel Adams drafted a report on the Sugar Act for the Massachusetts Assembly, in which he called the Sugar Act an infringement of the rights of the colonists as British subjects.

The Sugar Act was repealed in 1766 and replaced with the Revenue Act that same year, which reduced the tax to one penny per gallon on molasses imports.

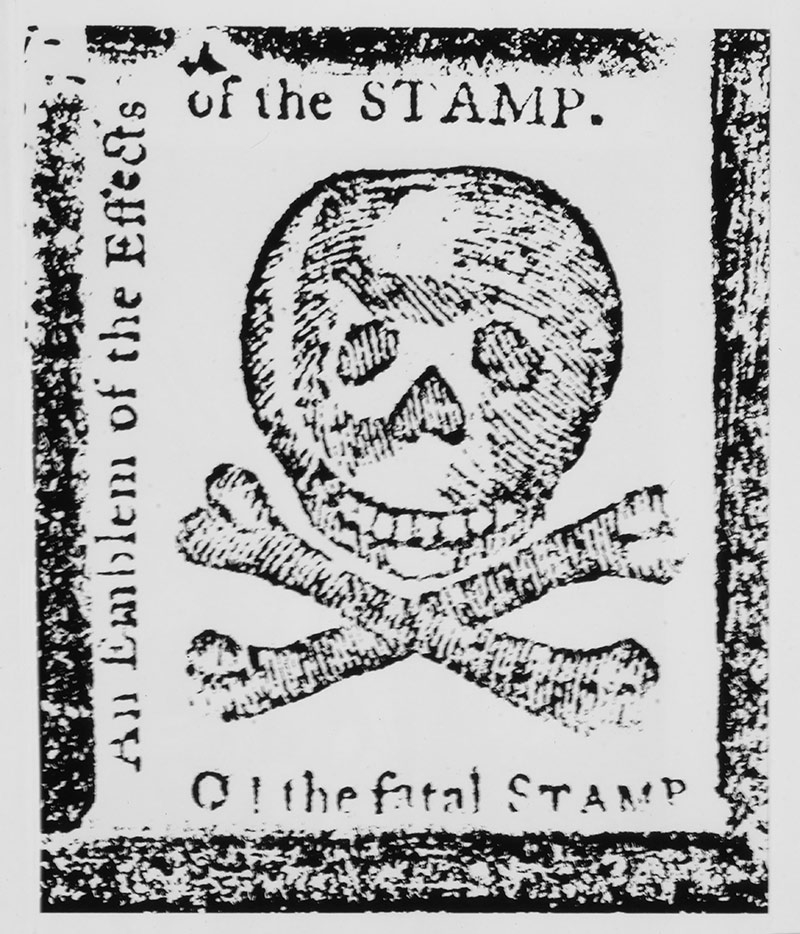

The British Parliament passed the Stamp Act in 1765, which required colonists to pay a new tax on most printed materials.

Adams supported the calls for a boycott of British goods to pressure Parliament to repeal the tax.

Riots from groups like the Loyal Nine, a precursor to the Sons of Liberty, during this time resulted in some homes and businesses being destroyed, and the jury is out on whether or not Adams was directly involved in directing violent agitators in protest.

Adams was appointed to the Boston Town Meeting in September of 1765 to write the instructions for Boston’s delegation to the Massachusetts House of Representatives, and he was selected to become a Representative for Boston later that same month.

Adams was the main author of several House resolutions against the Stamp Act, and he was also said to be one of the first colonial leaders to argue that mankind possessed certain natural rights that governments could not violate.

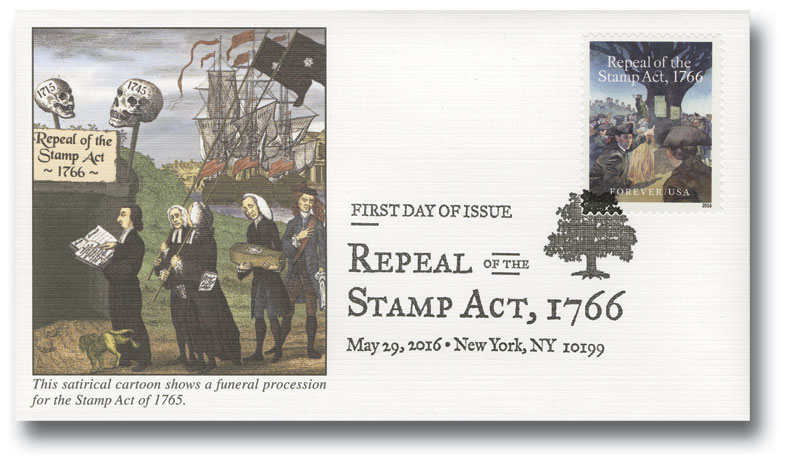

The Stamp Act did not go into effect when it was supposed on November 1st of 1765 because protestors throughout the colonies had forced stamp distributors to resign and the tax was subsequently repealed in March of 1766.

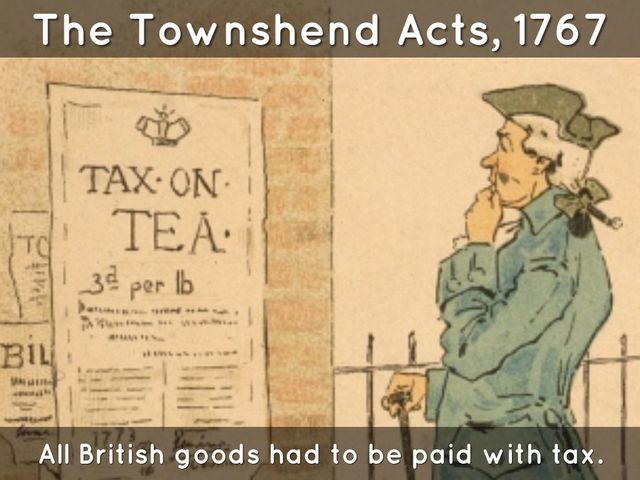

Next came the Townshend Acts.

The Townshend Acts were established by the British Parliament in 1767, establishing new duties on goods imported to the colonies to help pay for the costs of governing the American colonies.

The revenues generated from this were to be used to pay for governors and judges independent of colonial control and compliance enforced by the newly created American Board of Custom Commissioners, headquartered in Boston.

Resistance grew to the Townshend Acts and Samuel Adams organized an economic boycott through the Boston Town Meeting, and called for other towns and colonies to join the boycott.

Samuel Adams wrote what became known as the “Massachusetts Circular Letter,” calling on the colonies to join Massachusetts in resisting the Townshend Acts, which was approved by the Massachusetts House on February 11th of 1768, after having not been approved at first.

Lord Hillsborough, the British Colonial Secretary, instructed colonial governors to dissolve their assemblies if they responded to the letter, and directed the Massachusetts Governor, Francis Bernard, to have the Massachusetts House rescind the letter, which the House refused to do.

Governor Bernard dissolved the legislature after Samuel Adams presented another petition to remove the Governor from office.

The Commissioners of the Customs Board requested military assistance from Great Britain when they found they could not enforce trade regulations in Boston, and a 50-gun warship arrived in Boston Harbor in May of 1768, the HMS Romney.

Tensions escalated when the captain of the Romney began to forcibly impress local sailors to serve on the HMS Romney.

This led to Customs officials seizing a ship belonging to John Hancock named “Liberty” for alleged customs’ violations, and a riot broke out when sailors from the HMS Romney came to tow the “Liberty.”

This in turn led to Massachusetts Governor Bernard writing to London in response to this incident and requesting that troops be sent to Boston to restore order, and Lord Hillsborough ordered four regiments of the British Army there, with the first troops arriving in October of 1768.

In September of 1768, When Governor Bernard refused the request of the Boston Town Meeting to convene the General Court upon learning about the incoming British troops, the Boston Town Meeting called on other Massachusetts towns to send representatives to meet at Faneuil Hall starting on September 22nd, and one-hundred towns sent delegates to the convention, which issued a letter stating that Boston was a lawful town, and that the pending military occupation would violate the natural, constitutional, and charter rights of the citizens of Boston.

The British occupation of Boston was said to have been a turning point for Samuel Adams according to some accounts, who started working towards American independence and gave up hope for reconciliation with Great Britain.

He wrote a number of letters and essays against the occupation, considering it a violation of the 1689 Bill of Rights, which was an act of Parliament seen as a landmark in English Constitutional Law that laid out basic civil rights.

The “Journal of Occurrences” publicized the occupation of Boston throughout the colonies in a series of unsigned articles that may or may not have been written by Adams.

The articles were claimed to be a factual daily account of events in Boston under British occupation, depicting unruly British soldiers assaulting citizens on a regular basis with no consequences to them.

Publication of the “Journal of Occurrences” ended on August 1st of 1769, when Governor Bernard permanently left Massachusetts.

Two British regiments were removed from Boston in 1769, and two remained.

The Boston Massacre took place in March of 1770.

Five civilians were killed by British soldiers in a crowd of several hundred who were said to have been taunting the soldiers.

The incident was well-publicized by Samuel Adams and Paul Revere, and was depicted in Revere’s 1770 engraving pictured here.

The situation quieted down somewhat after the Boston Massacre, with Parliament repealing the Townshend Acts in April 1770, with the exception of the tax on tea.

Samuel Adams continued to urge the colonists to boycott British goods, but the boycott faltered because of the improvement of economic conditions.

Adams and his associates came up with a system of “Committees of Correspondence” between towns in Massachusetts in November of 1775, where they would consult with each other on political matters by way of messages sent through these committees that recorded British activities and protested British policies.

These committees of correspondence soon formed in other colonies as well.

The new Massachusetts Governor, businessman and Loyalist politician, Thomas Hutchinson, became concerned that the Committees of Correspondence System was becoming an independence movement.

The Governor addressed the Massachusetts legislature and argued that denying the supremacy of Parliament came dangerously close to rebellion.

Adams and the House responded to him by saying that the Massachusetts Charter did not establish Parliament’s supremacy over the province, so Parliament could not claim that authority.

This exchange was published and publicized in the widely distributed “Boston Pamphlet.”

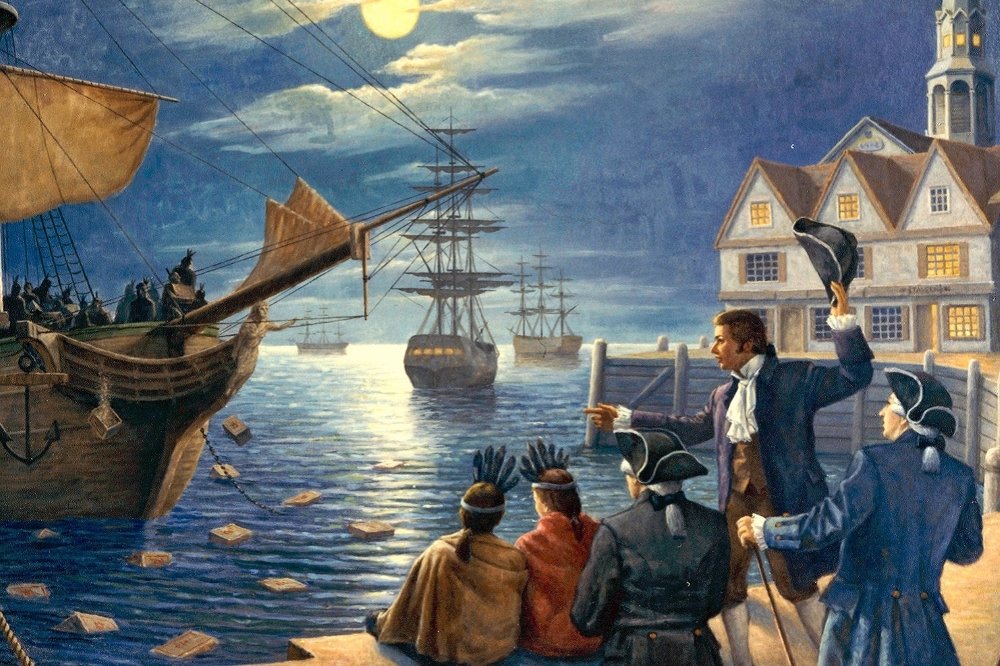

Samuel Adams was said to have been a leader in the events leading up to the Boston Tea Party that took place in December of 1773 in our historical narrative.

The British Parliament had passed the Tea Act in May of 1773 to help the British East India Company, who had amassed a surplus of tea that it could not sell.

The Tea Act allowed the East India Company to sell the tea directly to the colonies , granting them significant cost advantage over local merchants and reduction in their taxes paid in Great Britain while at the same time keeping the Townshend duty on tea imported in the colonies.

In late 1773, seven ships were sent to the colonies carrying the surplus tea, with four bound for Boston Harbor.

Adams and the Committees of Correspondence promoted opposition to the Tea Act, and with the exception of Massachusetts, every colony was successful in not having the tea delivered.

Governor Hutchinson was determined to hold his ground and have the tea delivered to those designated to receive it.

All other efforts to prevent the tea from being unloaded having failed, on the night of December 16th of 1773, approximately 342 chests of tea were dumped overboard in the course of three-hours by a large group of men known as the “Sons of Liberty.”

Samuel Adams publicized the event and defended it, arguing that the Boston Tea Party was not the act of a lawless mob, but the only remaining option left to people to defend their rights.

Great Britain’s response to the Boston Tea Party was the introduction of the Coercive, also known as Intolerable, Acts, of which the first was the Boston Port Act, enacted in March of 1774, and effective June 1st, which closed Boston’s commerce until the British East India Company had been repaid for the destroyed tea.

The May of 1774 Massachusetts Government Act rewrote the Massachusetts Charter, making numerous officials royally-appointed as opposed to elected.

Also passed by the British Parliament in May of 1774, the Administration of Justice Act allowed colonists charged with crimes to be transported to another colony or to Great Britain for trial.

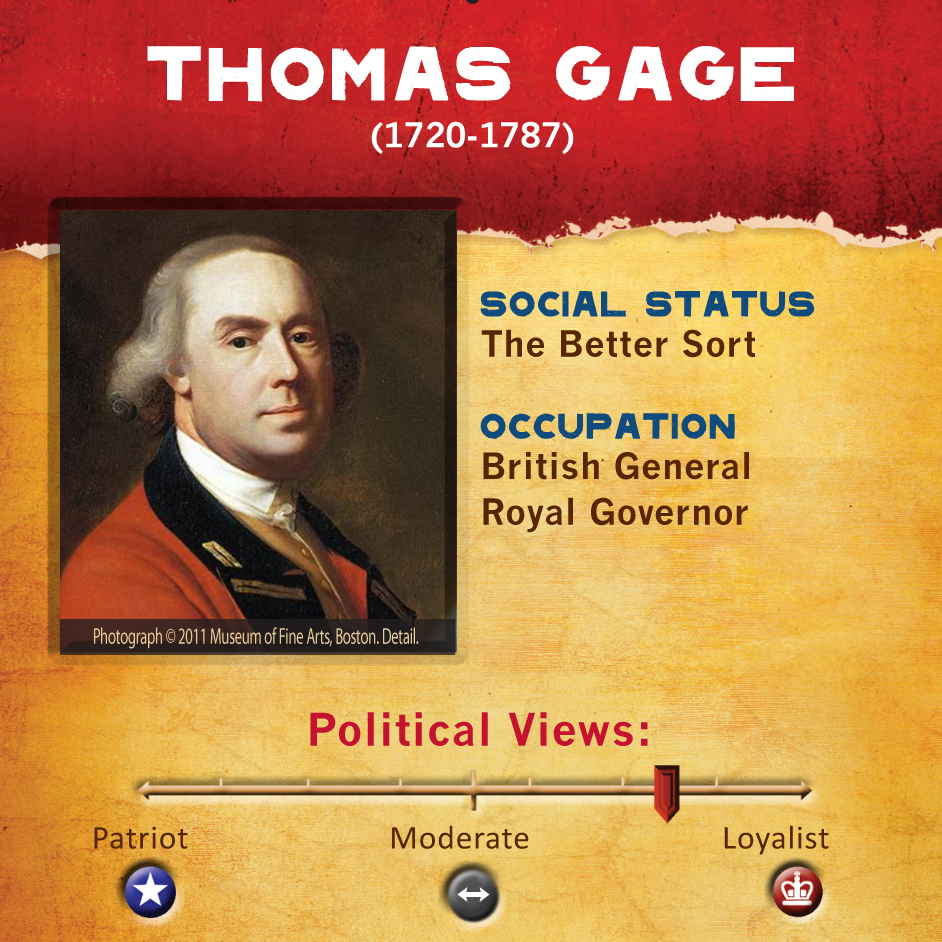

General Thomas Gage was the new Royal Governor of Massachusetts appointed to enforce the Coercive Acts, and he was also the commander of British Military forces in North America.

Samuel Adams worked to coordinate resistance to the Coercive Acts.

In May of 1774, with Adams moderating, the Boston Town Meeting organized a boycott of British goods.

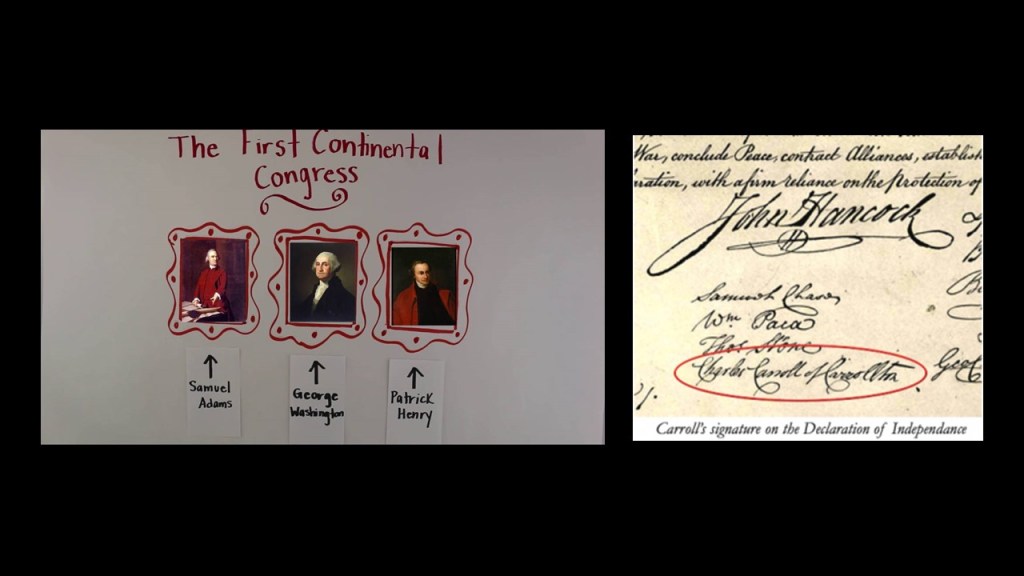

In June of 1774, he chaired a committee in the Massachusetts House behind locked doors which proposed what became the First Continental Congress in Philadelphia, and to which Samuel Adams became one of five delegates from Massachusetts.

The First Continental Congress took place at Carpenters’ Hall in Philadelphia between September 5th and October 26th of 1774.

Delegates from twelve of the thirteen colonies discussed how the colonies could work together in response to the British government’s coercive reactions in Massachusetts.

They agreed on a “Declaration and Resolves,” a statement that outlined colonial objections to the Coercive Acts, and concluded with the plan of the First Continental Congress to enter a boycott of British trade until the grievances were resolved.

They sent a petition to King George III pleading for resolution of their grievances and repeal of the Coercive Acts, which had no effect.

In November of 1774, Adams returned to Massachusetts and served in the Massachusetts Provincial Congress, which created the first Minutemen companies – militia ready to act on a moment’s notice.

Both selected as delegates to the Second Continental Congress in Philadelphia, which was scheduled to start meeting in May of 1775, Samuel Adams and John Hancock attended the Massachusetts Provincial Congress in Concord, Massachusetts, in April of 1775, and then decided to stay in Hancock’s childhood home in Lexington before heading to Philadelphia after deciding it wasn’t safe to return to Boston.

After having received a letter from Lord Dartmouth, British Secretary of State for the Colonies, on April 14th of 1775 advising arrest of the principal people of the Massachusetts Provincial Congress, General Gage, the Massachusetts Governor and commander of British Military forces in North America sent out a detachment of soldiers a few days later, on April 18th, to seize and destroy military supplies that the colonists had stored in Concord, and possibly to arrest Adams and Hancock, though this order is in dispute historically because it wasn’t in his written orders.

Regardless, the Patriots believed otherwise, and Paul Revere was dispatched on horseback from Boston on his famous midnight ride, to both alert the colonial militia that the “British are coming,” and warn Hancock and Adams about their potential arrest.

As Hancock and Adams made their escape, the American Revolutionary War began in Lexington and Concord on April 19th of 1775.

The exact role of Samuel Adams in the proceedings of the Second Continental Congress was not known because of its secrecy rule, but he was believed to have been a major influence in steering the Congress toward independence.

He served on numerous committees, including ones dealing with military matters, and it was he who nominated George Washington to be Commander-in-Chief of the Continental Army.

On June 7th of 1776, Samuel Adams’ ally, Richard Henry Lee from Virginia, introduced a three-part resolution calling for the Second Continental Congress to declare independence, create a colonial confederation, and seek foreign aid.

This resulted in the Continental Congress approving the language of the Declaration of Independence and its signing on July 4th of 1776.

Adams remained active in the Second Continental Congress, also having a hand in drafting the Articles of Confederation in 1777, the plan for colonial confederation, and he continued to serve on various military committees.

He retired completely from the Continental Congress in 1781.

Not bad for a guy who started out his career in the beer-making business!

Adams had returned to Boston in 1779 to attend a state constitutional convention, at which time he was appointed to a three-man committee to draft a new state constitution.

The new Massachusetts Constitution was amended by the convention approved by voters in 1780, and is among the oldest functioning constitutions in continuous effect in the world.

Adams continued to remain active in politics after his return to Massachusetts, putting his focus on the promotion of virtue.

He occasionally serving as moderator of the Boston Town Meeting, and he was elected to the State Senate.

Shays’ Rebellion took place in rural western Massachusetts from August of 1786 to February of 1787, in response to a debt crisis among the people and in opposition to the state government’s increased efforts to collect taxes on individuals and their trades.

Residents in these areas had few assets beyond their land, and bartered with each other for goods and services, as opposed to the market economy of the developed areas of Massachusetts Bay and Connecticut River Valley.

It was led by Revolutionary War veteran Daniel Shays who led 4,000 rebels in protest against economic and civil rights’ injustices.

Interestingly, where Samuel Adams approved of rebellion against an unrepresentative government, he opposed the taking up of arms against a Republican form of government, where problems should be remedied through elections.

He urged the Governor, James Bowdoin, to put down the uprising using military force, so he sent 4,000 militiamen to quell the uprising.

Shay’s Rebellion led to the creation of the United State Constitution, which started at the 1787 Philadelphia Convention, because it contributed to the belief that the 1777 Articles of Confederation needed to be revised.

The United States Constitution came into force in 1789 as the supreme law of the United States.

The original Constitution is comprised of seven articles.

Its first three articles embody the doctrine of “Separation of Powers;” its next three articles embody the concepts of “Federalism,” and the rights and responsibilities of state governments; and its last article established the procedure used to by the thirteen original states to ratify it.

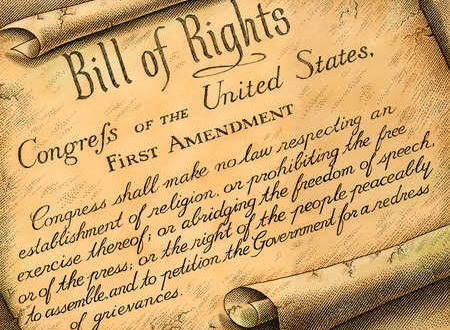

The first ten amendments to the Constitution are known as the “Bill of Rights,” which were ratified by the first U. S. Congress, on December 15th of 1791, offer specific protection for individual liberty and justice, and place restrictions on the power of government.

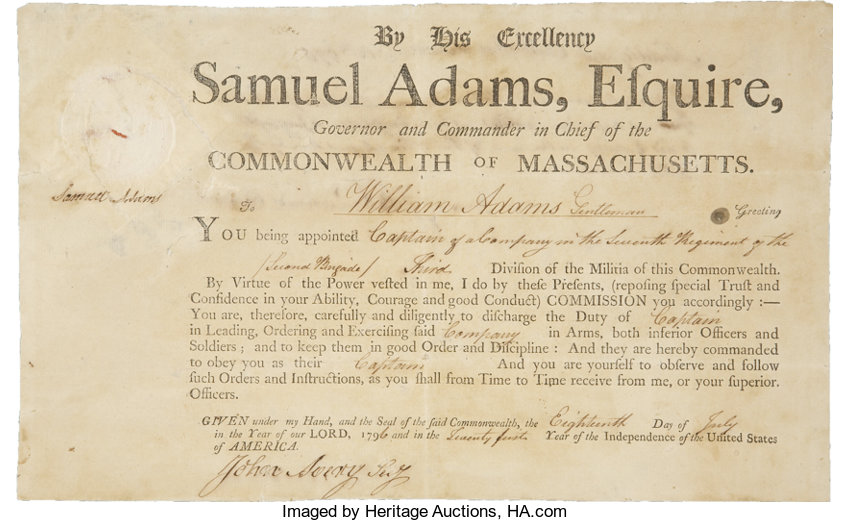

Samuel Adams was elected Lt. Governor of Massachusetts in 1789, a position in which he served until Governor John Hancock’s death in 1793, at which time he became acting governor.

The following year, Adams was elected as the Massachusetts Governor, a position in which he served between October of 1794 and June of 1797.

In Massachusetts, Samuel Adams was considered a leader of the Jeffersonian Republicans, also known as the Democratic-Republican Party, a political party founded by Thomas Jefferson and James Madison in the early 1790s that championed things like Republicanism, agrarianism, political equality and expansionism.

This was in opposition to the Federalist Party, a conservative party that was founded in 1789, and the first political party in the United States.

It was led by people like Alexander Hamilton and Samuel’s cousin John Adams, and favored centralization, federalism, modernization, industrialization, and protectionism.

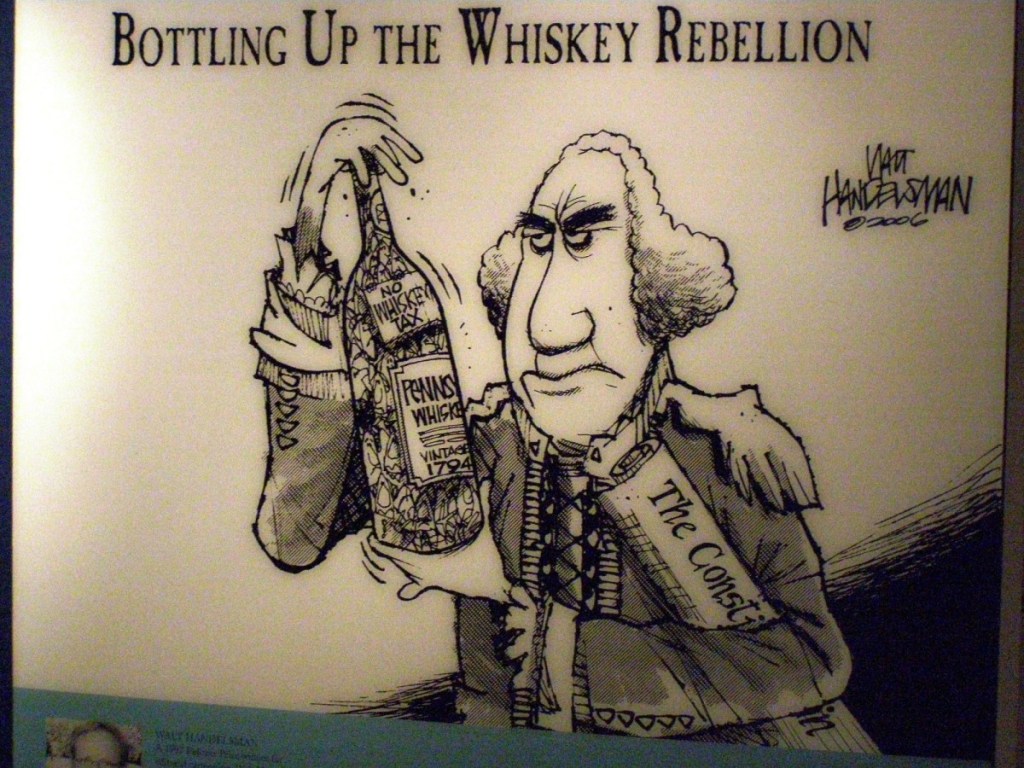

Samuel Adams supported the suppression of the Whiskey Rebellion for the the same reasons he supported the suppression of Shay’s Rebellion.

The Whiskey Tax was the first tax imposed on a domestic product by the newly formed federal government, and was intended to generate revenue for the war debt brought about by the Revolutionary War, and primarily affected people living in rural areas, like farmers in the new country’s western frontier who turned surplus grains into alcohol and where whiskey was used for bartering.

The Whiskey Rebellion was a violent tax protest in the United States that started in 1791 and ended in 1794 during George Washington’s Presidency, and when George Washington himself led 13,000 militiamen provided by Virginia, Maryland, New Jersey, and Pennsylvania, to put down the insurgency, however, all the insurgents left before the army arrived, effectively ending the rebellion, and resulting in a handful of arrests of individuals that were later acquitted or pardoned.

The Whiskey Rebellion demonstrated that the new national government had the will and ability to suppress violent resistance to its laws.

The Whiskey Tax was very difficult to collect, and was finally repealed in the early 1800s under President Thomas Jefferson.

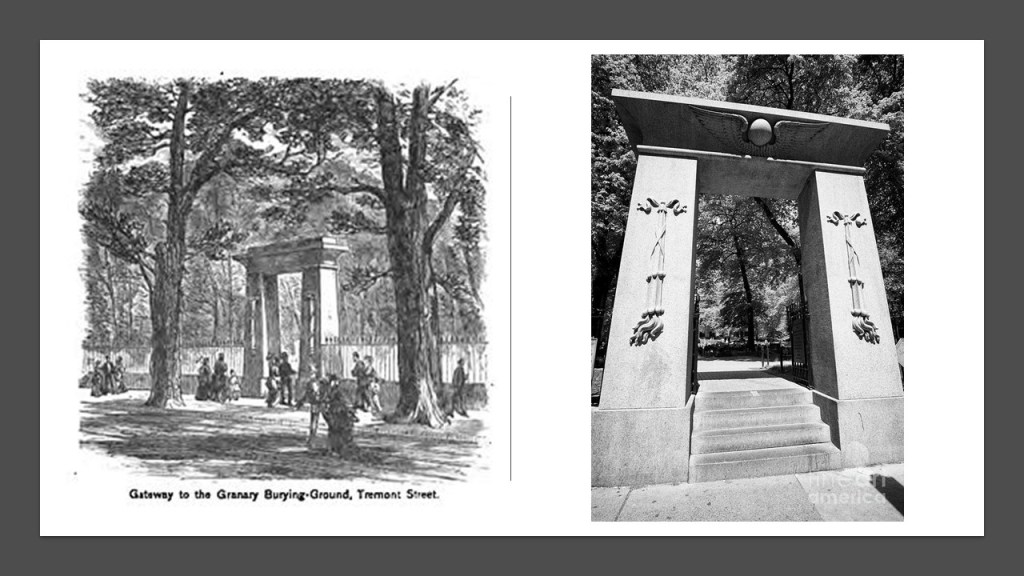

Adams retired from politics after his term as Governor ended in 1797, and he died on October 2nd of 1803, at the age of 81, and was buried in Boston’s Granary Burying Ground…

…and also where Paul Revere was laid to rest.

No mention of his famous midnight ride, or much of anything on his grave-marker.

Paul Revere’s grave-marker reminded me of the simple grave-markers at Boot Hill in Tombstone, Arizona, famous for the “Gunfight at O. K. Corral” between the Earps and the cowboy outlaws.

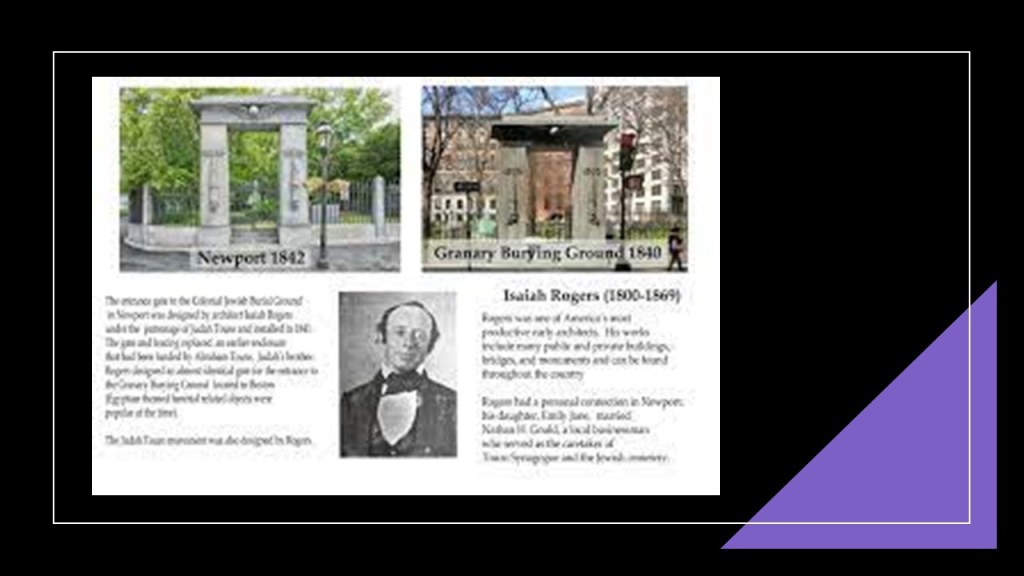

The Granary Burying Ground’s Gate and fence was said to have been designed in Egyptian-Revival-style by Isaiah Rogers in 1840…

…and Isaiah Rogers was said to have designed an identical gateway for Newport, Rhode Island’s Touro Synogogue Cemetery in 1842.

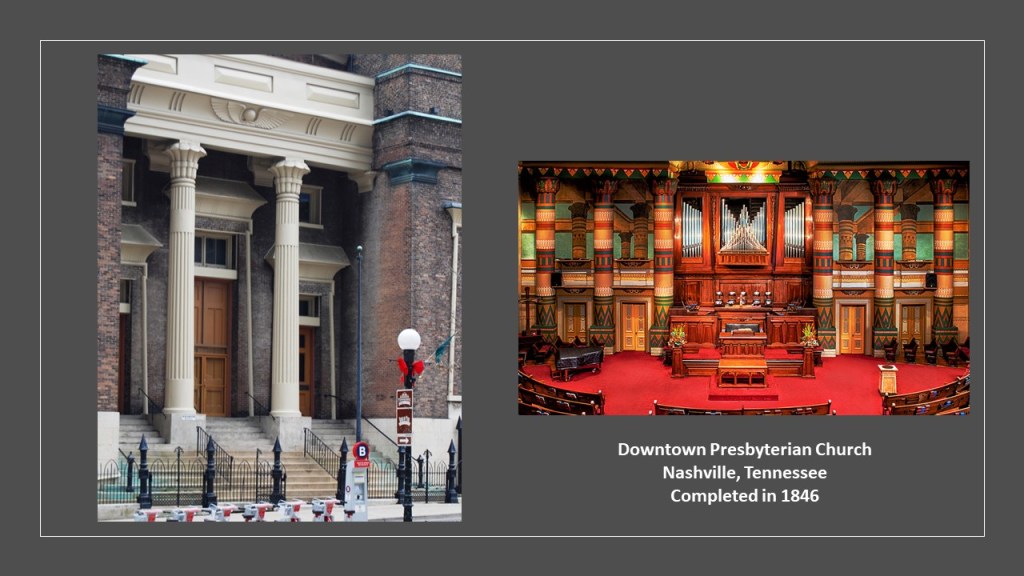

Speaking of Egyptian Revival Style architecture, there’s a stunning example of it at the Downtown Presbyterian Church in Nashville, Tennessee, said to have been designed by architect William Strickland, and completed in 1846.

One more thing before I move on.

This is what came up when I searched for “Was Samuel Adams a Freemason?”

I found Samuel Adams mentioned as a Freemason in an article from June of 2009 on the antiquesandthearts.com website about the Grand Lodge of Masons in Massachusetts celebrating 275 years of brotherhood.

The article mentioned things like the Green Dragon Tavern in Boston being the unofficial Headquarters of the American Revolution…

…as well as the meeting place for the Grand Lodge of Massachusetts, which had purchased the Green Dragon Tavern in 1764, and used it as a meeting place until 1818.

Also mentioned in this article is that it was the origin point for the Boston Tea Party participants and Paul Revere’s midnight Ride, as well as mentioning that there were Freemasons among the British soldiers occupying Boston, which are called “Brethren.”

So, who’s their loyalty to? Their countries or each other?

Samuel Adams was mentioned as a Freemason in this article…

…and I wonder if he belonged to the York Rite of Freemasonry, since there is what appears to be a Templar cross next to his gravestone, and “Knights Templar,” the final order joined in the York Rite…

…because Samuel Adams was not mentioned on the “Northern Masonic Jurisdiction of the Scottish Rite” website, but the following men were listed as Freemasons of the Independence.

George Washington.

Well, no surprise there. I knew that about him a long time ago, and it even says in the description that he was one of the most famous Founding Fathers and Freemasons in American History.

Benjamin Franklin.

No surprise there either, though I don’t think he was as well known to the general public as a Freemason as George Washington was.

The last two mentioned as Freemason on this website page were John Hancock…

…and Paul Revere.

Again, not surprising to find out these men were Freemasons, but it is very interesting to me in terms of what this might represent in the bigger picture of what has been actually been taking place on Earth, especially in light of the role played by other Freemasons in our historical narrative.

Next, Charles Carroll of Carrollton.

Charles Carroll of Carrollton represents the State of Maryland in the National Statuary Hall.

He was an Irish-American politician, planter, and the only Catholic signer of the Declaration of Independence.

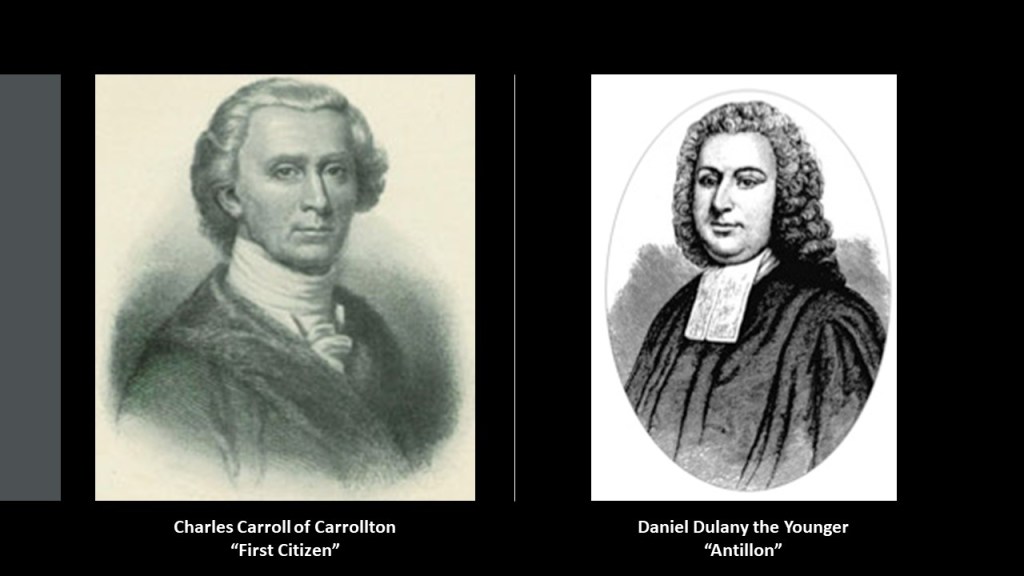

He was considered one of the Founding Fathers of the United States, and was known as the “First Citizen” of the American Colonies.

He received the “First Citizen” designation for the given reason this was his pen name for his articles in the “Maryland Gazette.”

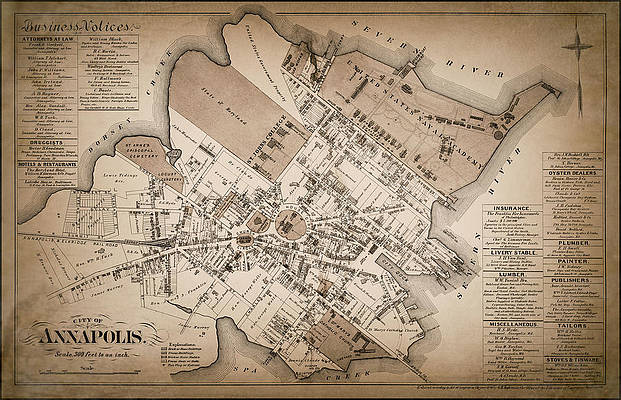

Charles Carroll of Carrollton was born in September of 1737 in Annapolis, Maryland, the son of Charles Carroll of Annapolis, a wealthy Maryland planter and lawyer, and the grandson of Charles Carroll the Settler, an Irishman who secured the position of Attorney General of the young colony of Maryland from George Calvert, First Baron Baltimore and immigrated there in October of 1688.

The Colony of Maryland was established in the 1630s on land granted by a hereditary charter to the Calvert family, and intended as a haven for English Catholics and other religious minorities.

The young Charles Carroll received a Jesuit education, starting at the Jesuit preparatory school at Bohemia Manor in Cecil County on Maryland’s Eastern Shore of the Chesapeake Bay…

…and then starting at the age of 11 was sent to Jesuit schools in France, including the College of St. Omer in northern France…

…and later the Lycee Louis-le-Grand in Paris, from which he graduated in 1755.

For the next 10 years, Carroll studied in Europe, and read law in London before returning to Annapolis in 1765.

He was granted Carrollton Manor, known as D0ughoregan Manor, by his father, which was why he received the name “Charles Carroll of Carrollton.”

Doughoregan Manor is located west of Ellicott City, Maryland, and was designated a National Historic Landmark in 1971.

As a Catholic, Charles Carroll of Carrollton was barred by Maryland Statute from entering politics, practicing law and voting.

This did not stop him from becoming not only one of the wealthiest men in Maryland, but of anywhere in the British Colonies, with his extensive agricultural estates, which besides Doughoregan, included Hockley Forge and Mill, called a collection of colonial-era industrial buildings along the Patapsco River near what is now Elkridge, Maryland, and Carroll provided the capital to finance new enterprises on the Western Shore of the Chesapeake Bay.

In the early 1770s, when the dispute between Great Britain and her colonies in America became more intense, Carroll engaged in a debate via letters that were written anonymously and published in the Maryland Gazette.

Carroll under the pen name of “First Citizen” argued for maintaining the right of the colonies to control their own taxation, becoming a prominent spokesman against the Governor’s proclamation increasing legal fees to state officers and Protestant clergy.

Daniel Dulany the Younger, a noted lawyer and British loyalist politician in Maryland, opposed Carroll in these written debates, writing as “Antillon.”

Carroll’s fame and notoriety began to grow as the identity of the two anonymous debaters became known, and following these written debates, Carroll became a leading opponent of British rule and served on various committees of correspondence, and believed that only the violence of war could break the impasse with Great Britain.

He was a delegate to the Annapolis Convention, the revolutionary government of Maryland before the Declaration of Independence was signed.

Charles Carroll was elected to the Second Continental Congress on July 4th of 1776, arriving too late to vote on it, but he was there to sign it.

At the time, he was the richest man in America.

He remained a delegate of the Second Continental Congress until 1778, and during his term, he served on the War Board and gave considerable financial support to the Revolutionary War.

Carroll returned to Maryland in 1778 to help form the state government there.

He declined re-election to the Continental Congress in 1780, but was elected to the Maryland Senate in 1781, and served there until 1800.

I guess by that time, Catholics were no longer barred y statute from hold political office.

He was also elected to the U. S. Senate during this time by the State Legislature, in which he served from March of 1789 to November of 1792.

He had to resign his U. S. Senate seat, however, because Maryland passed a law barring anyone from serving in state and federal office simultaneously, and he preferred his State Senate job.

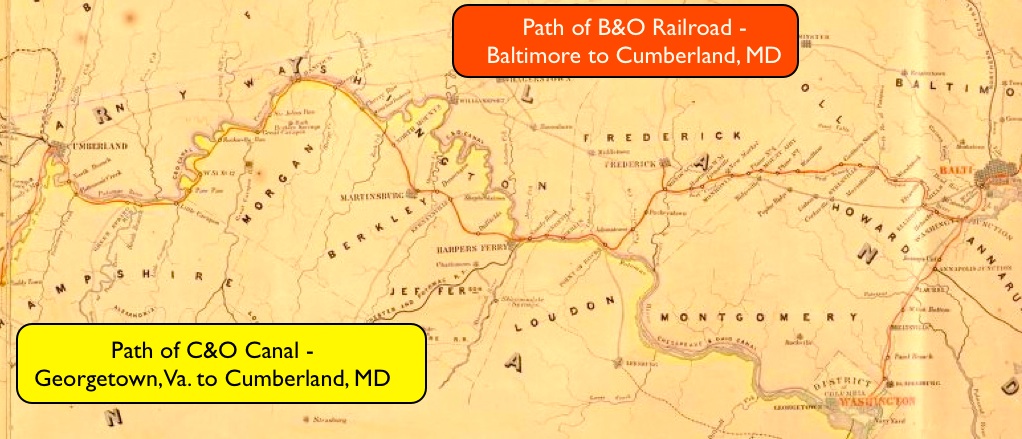

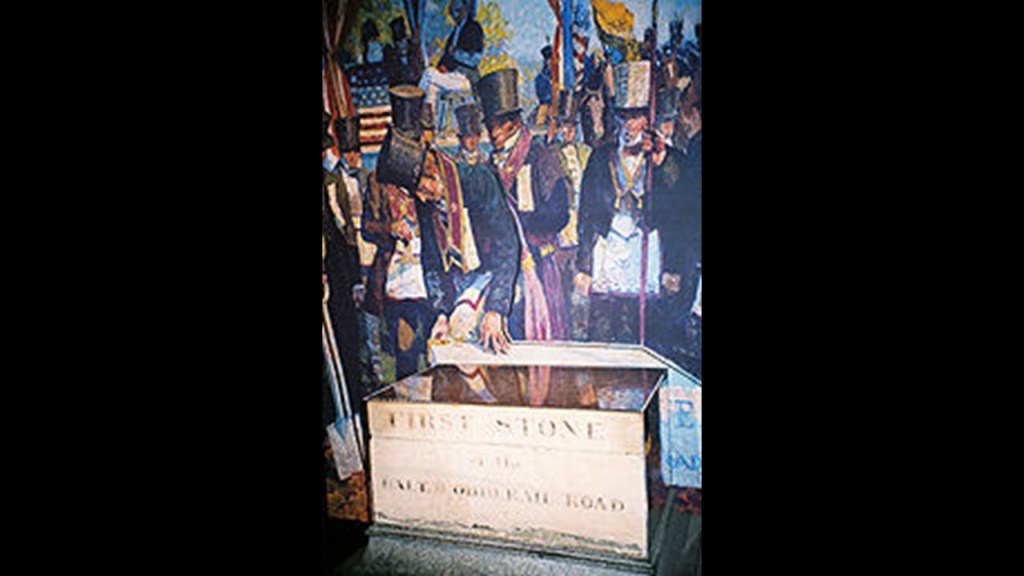

After retiring from public life in 1801, Carroll helped established the Baltimore & Ohio Railroad, which was founded in 1827 and broke ground for the construction of its headquarters and America’s first commercial railroad tracks on July 4th of 1828.

This is where aspects of the influential Carroll family of Maryland and Charles Carroll’s life and the history of the B & O Railroad intersect.

Mount Clare is called the oldest Colonial-era structure in Baltimore, Maryland, and was built on a Carroll-family plantation starting in 1763 by Charles Carroll the Barrister, a distant cousin of Charles Carroll of Carrollton.

This is what we are told.

The street grid of the city of Baltimore near Mount Clare began to grow and inch towards the southwest, with the dense development of streets and alleys of different styles of brick row-houses by the 1820s, and there was competitive economic pressure with the opening of the Erie Canal to develop the Port of Baltimore and the accompanying transportation systems like the Baltimore & Ohio Railroad with this new transportation technology from Great Britain and the proposed Chesapeake & Ohio Canal, of which both projects broke ground on the same day – July 4th of 1828 – and that there was an intense rivalry between the two.

The Baltimore & Ohio Railroad Company was formed in 1827, of which Charles Carroll of Carrollton was one of its Directors, and he was the one that had the honor of laying the first stone for the railroad at the ceremony after the celebratory festivities at the July 4th ground-breaking in 1828, near the Mount Clare Mansion.

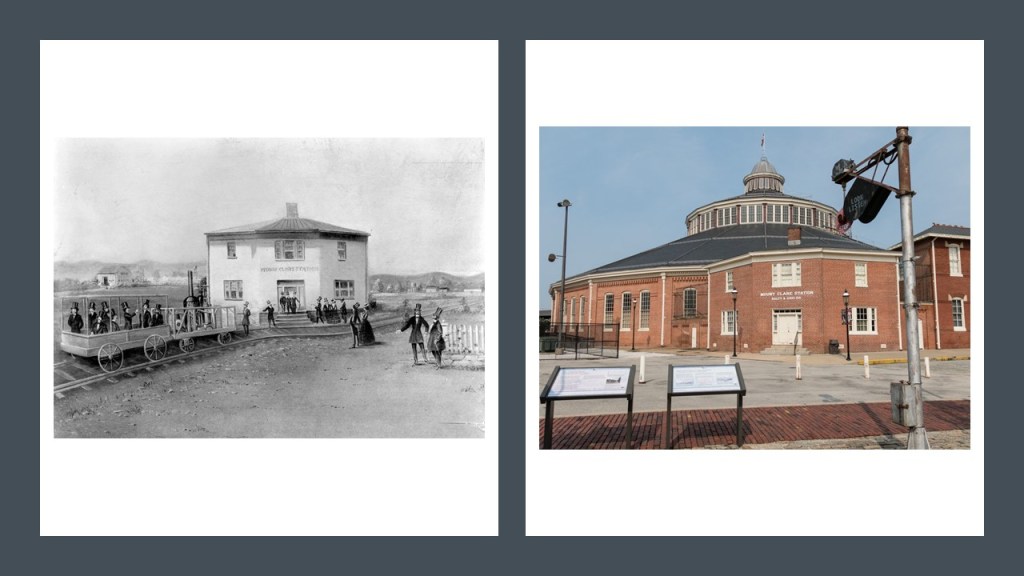

The Mount Clare Shops, of which this aerial photo is circa 1971, is the oldest railroad manufacturing complex in the United States, located on a portion of the Carroll family’s Mount Clare Estate, and the mansion left the family’s ownership in 1840.

Mount Clare Station was first said to have been erected in the 1830s and the Roundhouse in 1884, with the current Mount Clare Station building having been constructed in 1851.

Today the Baltimore & Ohio Railroad Museum, we are told the original Mount Clare passenger station, the first in the nation, was abandoned, and was located where the parking lot is for the museum is today.

Carroll was elected into the American Antiquarian Society in 1815, a national research library of pre-20th-century American history and culture, and the oldest historical society with a national focus, having been founded in 1812.

Its mission is to collect, preserve, and make available for study all printed records of what is known as the United States of America.

The seal of the American Antiquarian Society translates from the Latin of Ovid’s Metamorphoses, Book 15, Line 872: “Now I have completed my work, which neither sword nor devouring Time will be able to destroy.”

The written word can be manipulated to put out the narrative you want for posterity.

Architecture not so much.

This is the American Antiquarian Society building in Worcester, Massachusetts, said to have been designed by the arciectural firm of Winslow, Bigelow & Wadsworth in Georgian or Colonial-Revival style and completed in 1910.

Carroll died at the age of 95 in November of 1832, the oldest-lived Founding Father.

His funeral took place at the cathedral in Baltimore…

…and he was buried in the Manor Chapel on his estate at Doughoregan.

I am bringing forward unlikely pairs of historical figures who are represented in the National Statuary Hall who have things in common with each other, as mentioned at the beginning of this post.

The main thing that jumps out in this pairing is that both Samuel Adams and Charles Carroll of Carrollton are considered Founding Fathers of the United States.

Both men were well-educated for their day, with Samuel Adams earning a Master’s Degree at Harvard University in 1743, and Charles Carroll attending several prestigious Jesuit schools in France, graduating from the Lycee Louis-le-Grand in Paris, in 1755.

Both men were highly involved in using the written word in their political activism against the British, with the examples of Samuel Adams starting in 1748 in writing articles against British colonial policies for the Independent Advertiser and Charles Carroll’s role as the “First Citizen” in the written debate in the Maryland Gazette with Daniel Dulany the Younger as “Antillon.”

And both men were highly involved on both the local and Continental Congress-levels with events leading up to and during the American Revolutionary War.

These two men in particular fall into the category of key players in the historical narrative in shaping and forming what became the United States moreso than some of the rather obscure historical figures that are also honored there,

But regardless of fame or obscurity, I finding that the National Statuary Hall functions more-or-less as a “Who’s Who” for the New World Order and its Agenda, with the details of their lives and times taht are findable in a search telling a completely different kind of story than what we normally hear about our history.