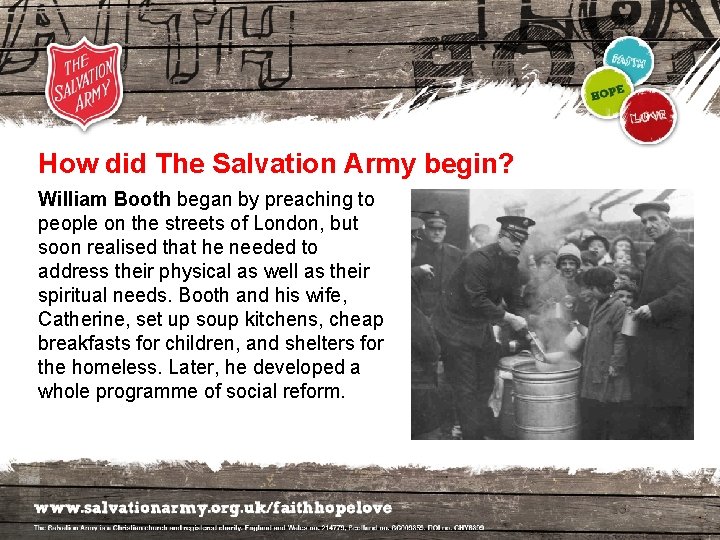

The Salvation Army was one of the earliest NGOs, along with “Anti-Slavery International,” the “YMCA,” and the “American Red Cross,” and was first established as a protestant church in 1865.

It is interesting that when you delve into specific Non-Governmental Organizations, invariably there are more questions than answers as the perception of NGOs by the general public is that they are benevolent and philanthropic organizations with a stated purpose of helping Humanity in a particular area or time of need, particularly since they are formed independently from government.

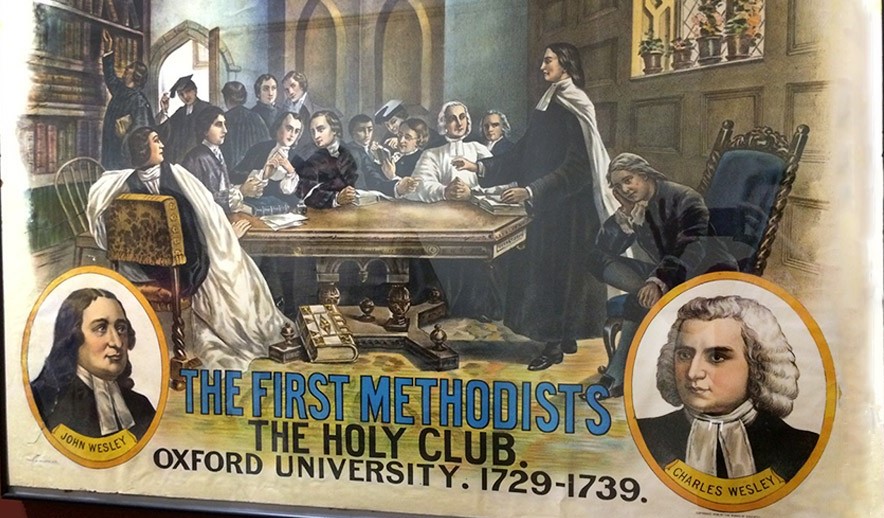

The theology of the Salvation Army comes from Methodism, a revival movement within the Church of England which started in the 18th-century and was based on the teachings of John and Charles Wesley & George Whitefield.

The Salvation Army is distinctive in its practices.

One is its use of designating its ministers as “officers” by using military ranks, beginning with Lieutenant and going all the way up to General.

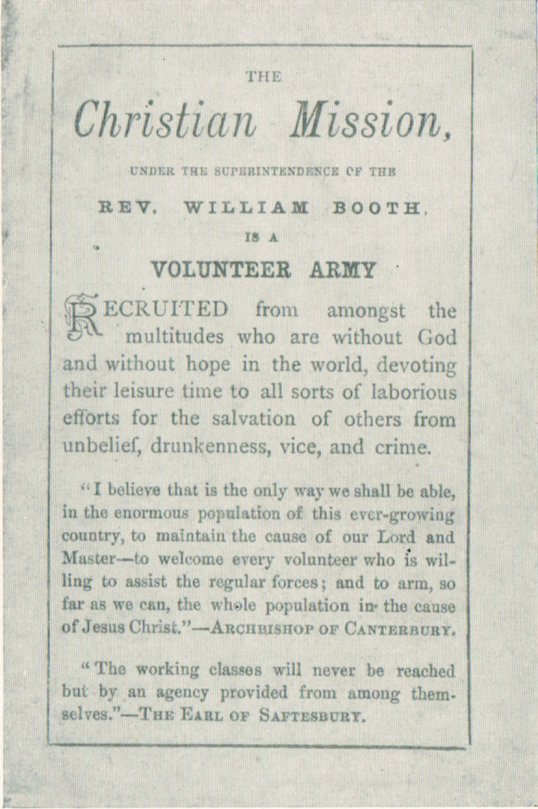

This is what we are told about the origins of the Salvation Army.

It was founded in 1865 by Methodist-Reform Church Minister William Booth and his wife Catherine Booth as the “East London Christian Mission.”

This name was used until 1878, when the mission became known as the “Salvation Army” and officially modelled after the army, with William Booth becoming the “General,” and his wife Catherine became known as the “Mother of the Salvation Army.”

William focused on converting poor Londoners, including prostitutes, gamblers, and alcoholics to Christianity, who were its main converts.

Catherine focused on speaking to wealthy people to gain financial support for their work, as well as acting as a minister.

William Booth described the Salvation Army’s work with the down-and-out as the three S’s: soup; soap; and salvation.

In 1880, the Salvation Army started its work in three other countries – the United States; Ireland; and Australia.

We are told the Salvation Army’s reputation improved in the United States as a result of its disaster relief efforts following the 1900 Galveston Hurricane…

…and the 1906 San Francisco earthquake and fire.

Today, the Salvation Army is in administered primarily in 5 regional zones, encompassing 128 countries, and is one of the world’s largest providers of social and humanitarian aid.

All this sounds really great, and I, among many others, have admired and supported the Salvation Army in my life.

I am going to dig around the personal histories of the founders William Booth and Catherine Booth, and see what turns up.

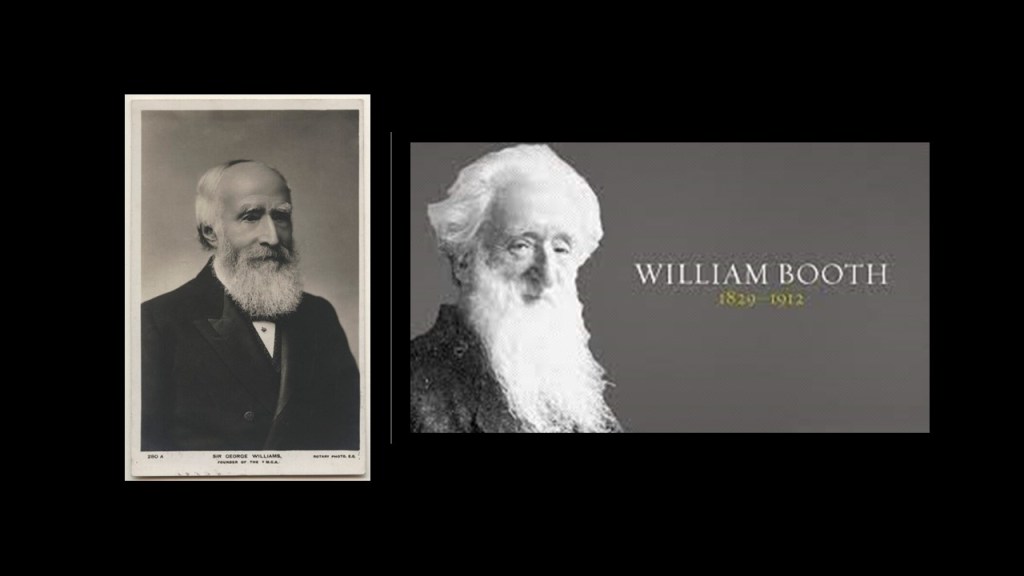

First, William.

William Booth was born in April of 1829 in Nottingham, England, to a family that went from relative wealth to poverty, and in 1842, William was apprenticed to a pawnbroker at the age of 13.

Bear in mind that George Williams was apprenticed to a draper in 1841, three-years before he founded the YMCA, as mentioned previously.

They even bore a resemblance to each other in their later years.

Also, like George Williams, who converted to Congregationalism from Anglicanism after becoming an apprentice, William Booth converted to Methodism after becoming one.

Booth proceeded to train himself in writing and speech in order to become a Methodist preacher, and from there became an evangelist, and along with his friend Will Sansom, preached to the poor and sinners of Nottingham in the 1840s, and he continued to preach in the open-air when he moved to London in 1849.

In 1851, Booth became a full-time preacher for the Methodist Reform Church.

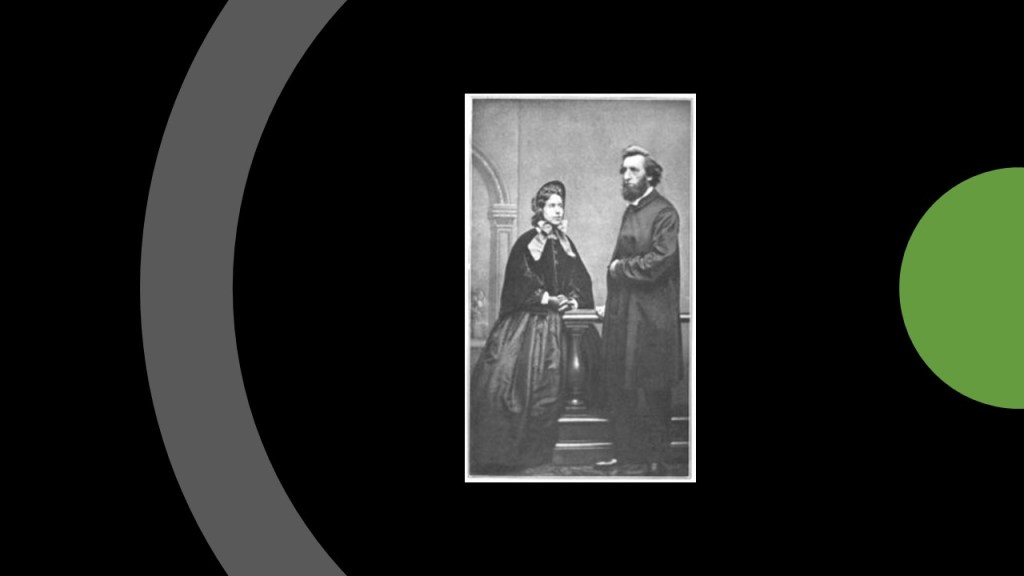

He and Catherine Mumford became engaged in 1852, and were married three-years later.

Like her husband, Catherine Mumford Booth was born in 1829, though she was born to Methodist parents and had a strong Christian upbringing.

She was particularly concerned about the problems of alcoholism and was secretary of a Juvenile Temperance Society.

She was also a member of the Band of Hope, a Christian charity in the UK which educates children and young people about drug and alcohol abuse.

Band of Hope meetings started in 1847, and in 1855 it became a formal organization.

In 1850, when Catherine refused to condemn the Methodist Reformers, the Wesleyan Methodists expelled her.

She met William Booth, who had also been expelled by the Wesleyans for reform sympathies, at the home of Edward Rabbits in 1851, and they married in 1855.

Rabbits was a Methodist Reformer who also established one of the largest shoe factories in the world, and his financial backing helped William Booth establish the Salvation Army.

Within Methodism, William Booth preferred evangelism to pastoring, and he became an independent evangelist when he was barred from evangelical campaigning in Methodist congregations.

By 1865, William and Catherine Booth had opened the “Christian Revival Society” in London’s East End, which was subsequently renamed the “Christian Mission,” then the “East End Christian Mission.”

Among other things, they created homeless shelters and soup kitchens during this time.

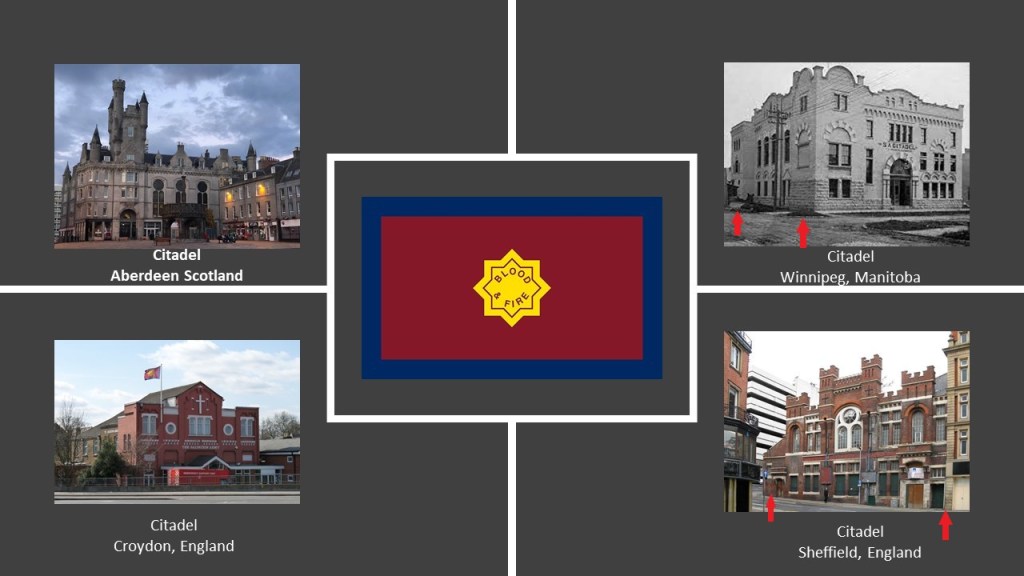

In addition to the Salvation Army’s churches around the world, known as “Corps,” or “Barracks” or “Temples” or “Citadels,” of which I have included several examples of citadels here, showing lovely old Castle or Cathedral-like buildings, two of which show classic evidence of mud-flood, with the slanting road and un-level windows…

…the Salvation Army is known for things like its Thrift Stores…

…Adult Rehabilitation Centers…

…homeless shelters…

…children’s homes for orphans…

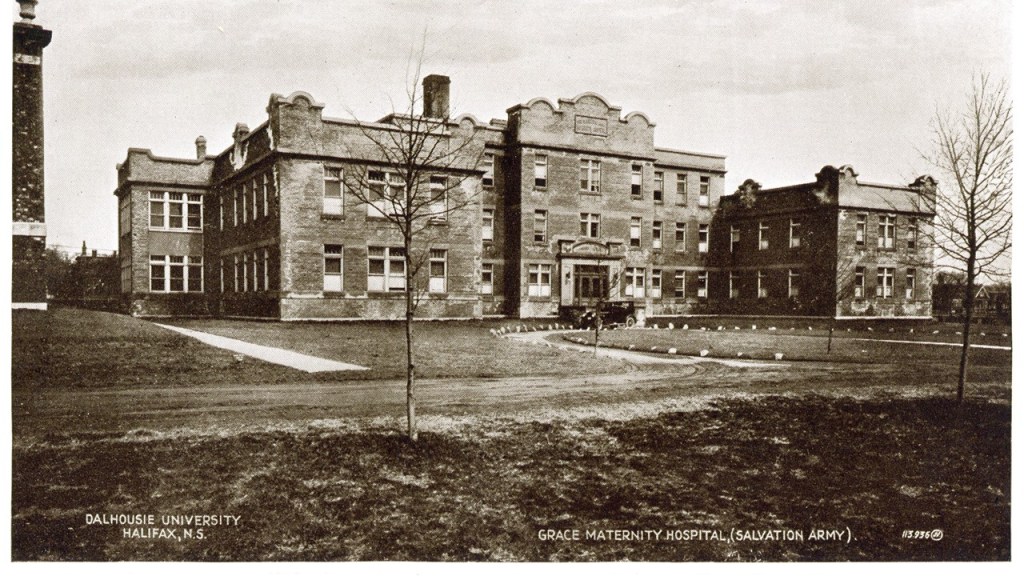

…Mother and Baby homes…

…and Maternity hospitals, to name a few of their human and social services.

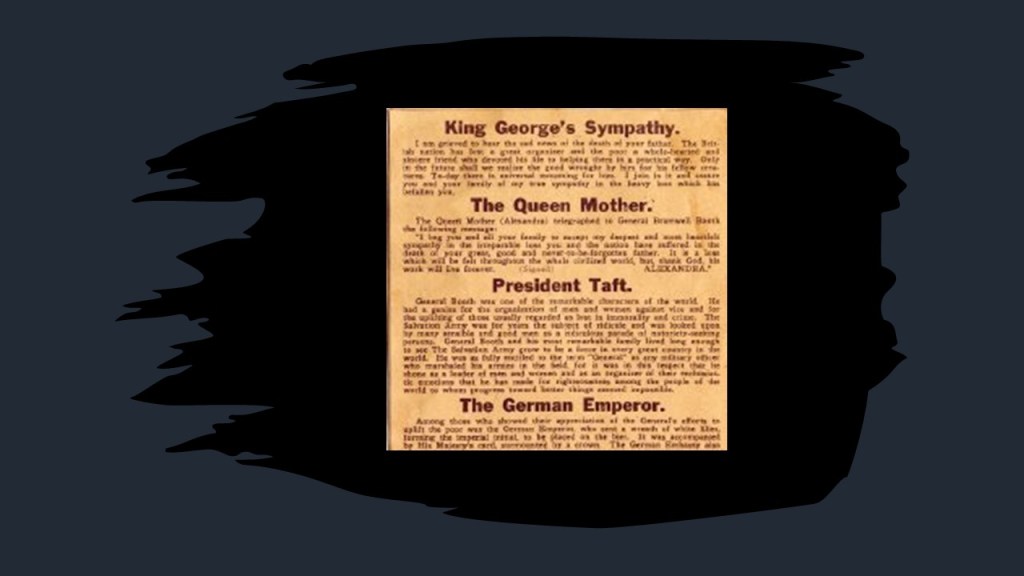

While William Booth and the Salvation Army had its detractors, towards the end of his life, he was received and admired by kings, emperors, and presidents.

When William Booth died in August of 1912, his body lay-in-state for three-days at Clapton Congress Hall, where 150,000 people were reported filing by his casket…

…and his funeral service was held at London’s Olympia, attended by 40,000 people, including Queen Mary…

…and Catherine Booth received a similar send-off when she died before her husband, in October of 1890.

William and Catherine were buried together at the Abney Park Cemetery in London, which was the main burial ground for the non-conformist ministers of the 19th-century.

So this is the conventional version of what we are told about the Booths, and their popularity and reach.

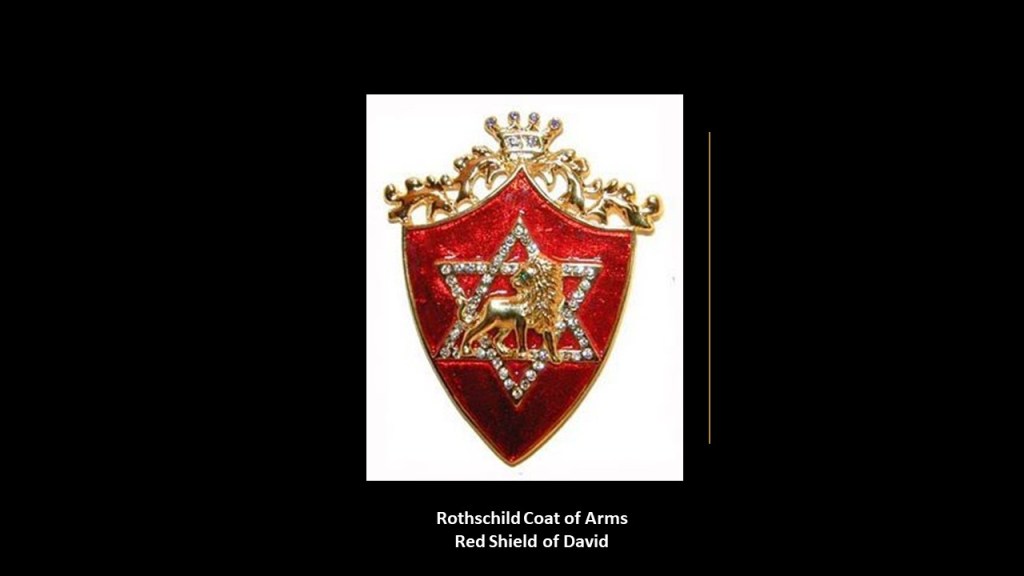

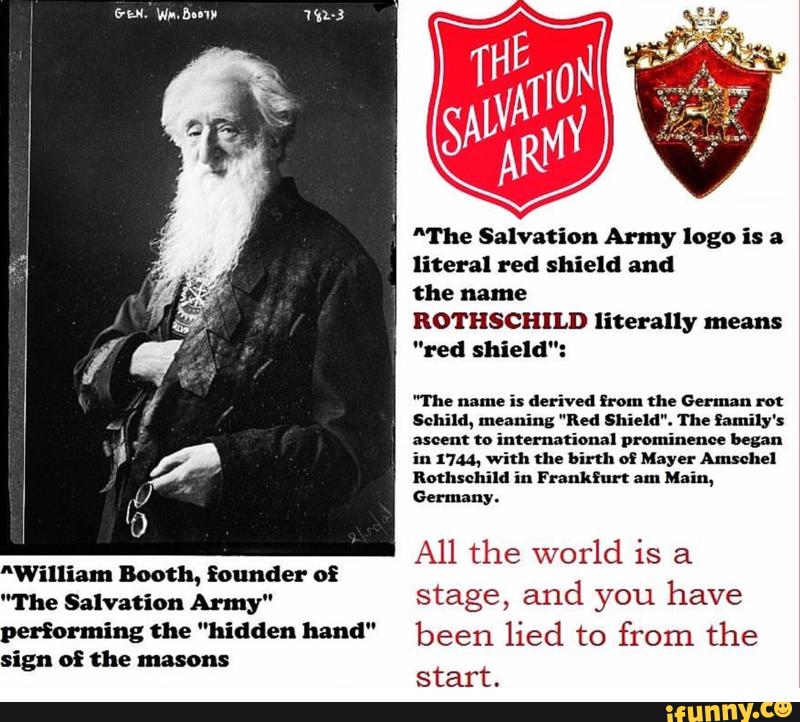

Let’s start with the Salvation Army shield seen at their gravesite.

The red shield is an internationally-recognized symbol of Salvation Army front-line service to those in need.

This is the Rothschild Coat of Arms.

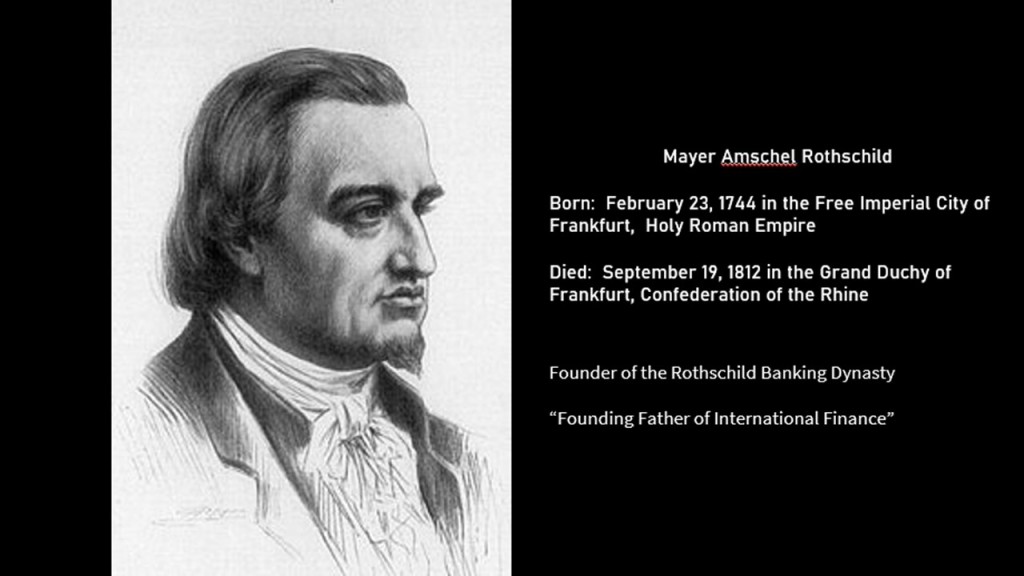

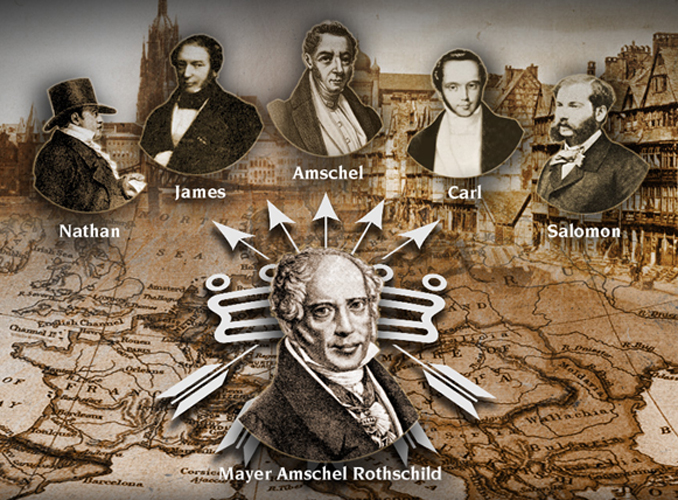

The Rothschilds were an Ashkenazi Jewish family from Frankfurt that gained prominence through Mayer Amschel Rothschild, who was born in Frankfurt in 1744 when it was part of the Holy Roman Empire, and died there in 1812, when it was part of the Confederation of the Rhine.

The family was said to have gotten its name from the house lived in by an ancestor of Mayer Amschel Rothschild, who lived at “the House of the Red Shield” in what was called the Frankfurt Judengasse, or the Jewish ghetto of Frankfurt.

Mayer Amschel Rothschild established an international banking family empire through his five sons:

His son Nathan, for example, settled in Manchester, England in 1798.

Nathan established a business in textile trading and finance, and made a fortune in a banking enterprise he began in London in 1805 that dealt in foreign bills and government securities.

Nathan had become a freemason in London of the “Emulation Lodge, No. 12, of the Premier Grand Lodge of England” in October of 1802.

By the time of his death in 1836, Nathan Mayer Rothschild had secured the position of the Rothschilds as the preeminent investment bankers in Britain and Europe, and his own personal net worth was over 60% of the British national income.

So was the emblem of the red shield of the Salvation Army a random choice, or was there a connection to the Rothschilds?

I had heard about this potential connection awhile back, but this is the first time I have looked into it myself, and was how I knew to look for it.

Some people certainly believe there was a connection.

I even found this reference alluding to the possibility that William Booth was himself a Freemason.

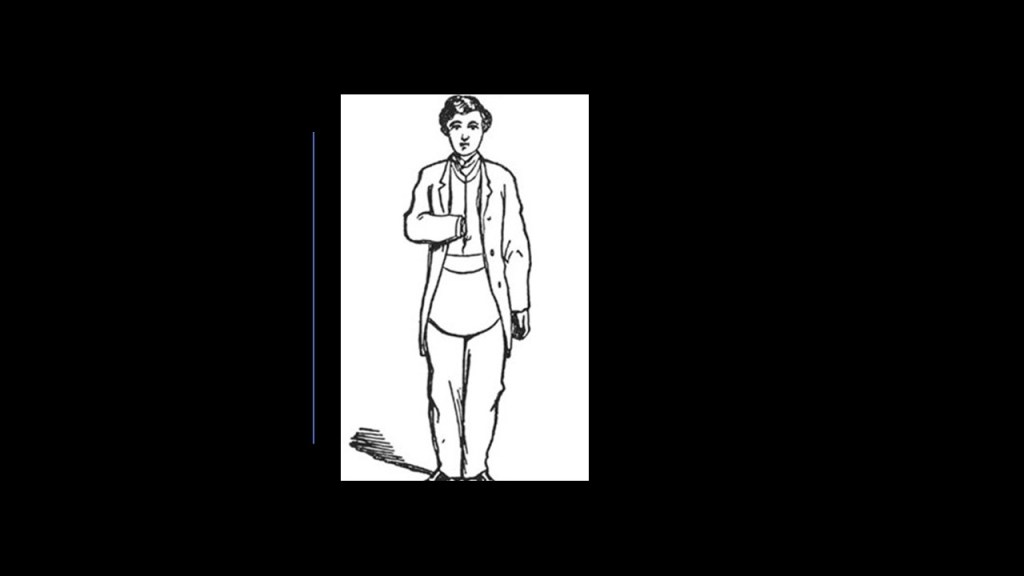

The Hidden Hand refers to the Freemasonic pose in this illustration, signifying “Master of the Second Veil.”

Here’s another possible masonic connection worth mentioning, that I thought about when I was looking into Catherine Mumford Booth and her interest in the temperance movement from a young age.

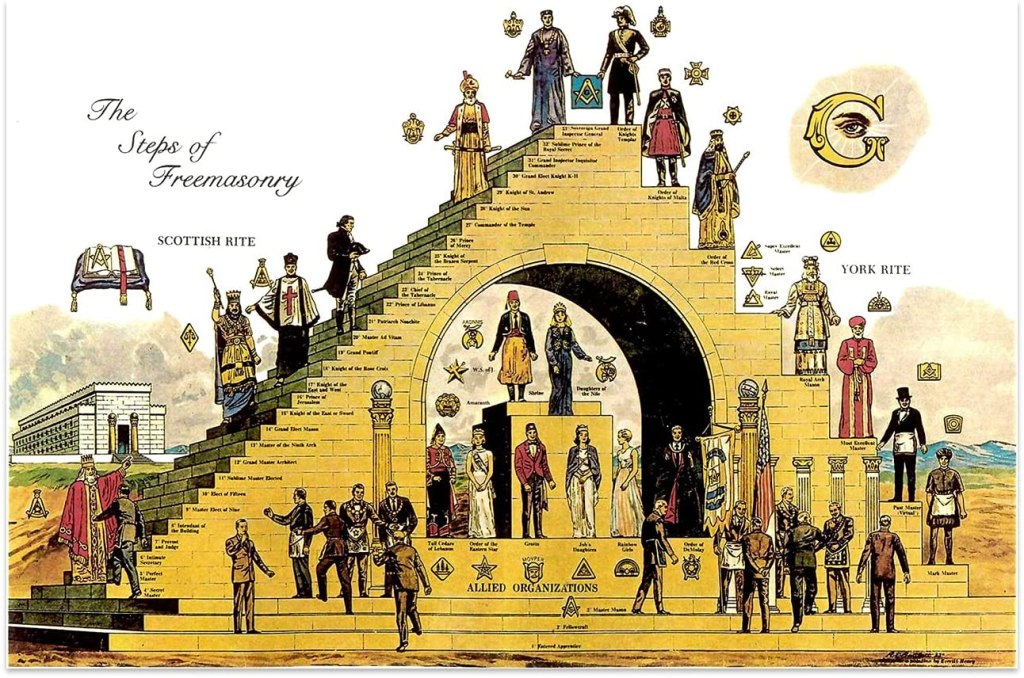

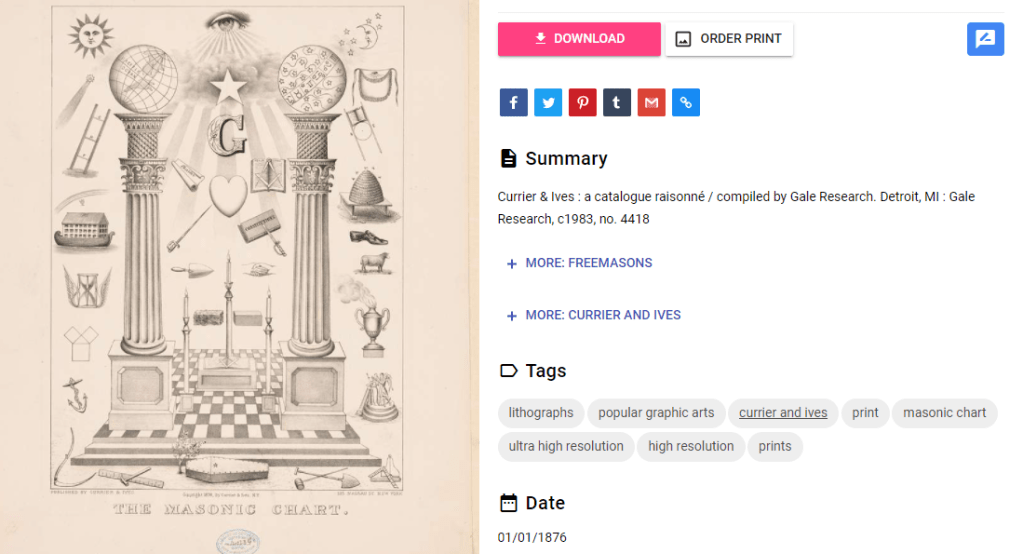

This is a common illustration depicting “The Steps of Freemasonry.”

In western freemasonry, a mason’s first step involves becoming an “entered apprentice,” which goes to the third step.

The “entered apprentice” can either stay there, which is what most freemasons do, or if he decides to go into the hierarchy, would either enter the Scottish Rite or the York Rite.

In the Scottish Rite, there are 30-steps, or degrees, and in the York Rite, 10-steps or degrees.

The highest degree in the Scottish Rite is the 33rd-degree, and in the York Rite, it is the order of the Knight Templar.

The Temperance Movement was a social movement against the consumption of alcohol that gained momentum starting in the 1820s.

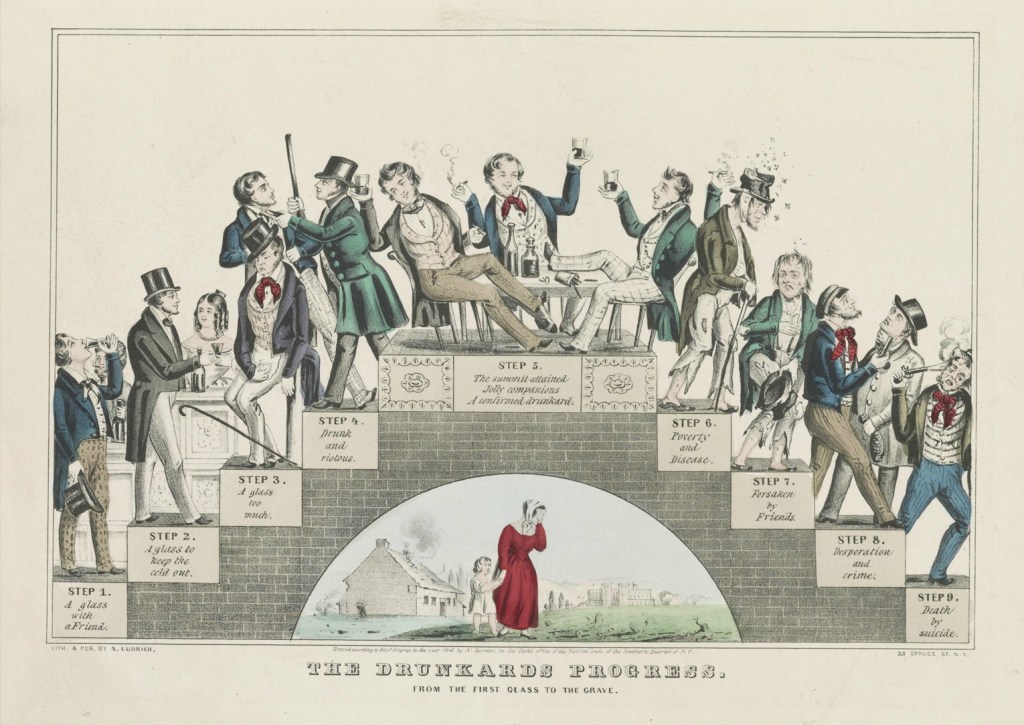

This was Nathaniel Currier’s depiction showing how moderate drinking leads to disaster step-by-step called “The Drunkard’s Progress,” looking a lot like the depiction of “The Steps of Freemasonry.”

Even recovery programs like Alcoholics Anonymous refer to “steps.”

I can’t seem to find out directly if Nathaniel Currier, an American lithographer who headed the company of Currier and Ives, was a freemason, but judging from this Currier and Ives lithograph called “The Masonic Chart” there seems to be more than a passing familiarity with freemasonry within the lithography firm

What I find interesting about all this interest in temperance was that the establishment was pumping out alcoholic beverages to the people in vast quantities during this same period of time.

Distilleries and breweries were going up literally everywhere.

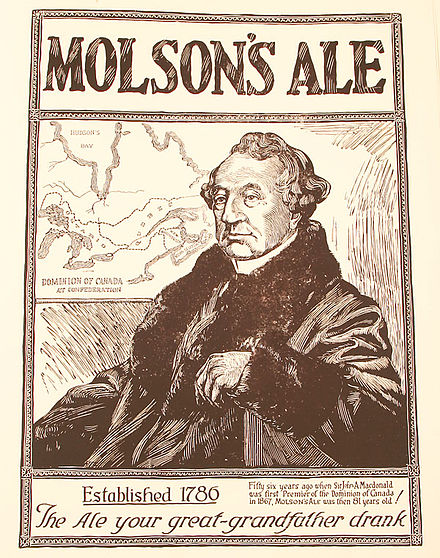

Just a couple of countless examples include Molson’s brewery in Montreal.

Between 1788 and 1800, John Molson’s business quickly grew into one of the larger ones in Lower Canada, having sold 30,000 gallons, or 113,500-liters, of beer by 1791.

John Molson was a freemason, and appointed the Provincial Grand Master of the District Freemasonic Lodge of Montreal in 1826, a position he held for five years before resigning in 1831.

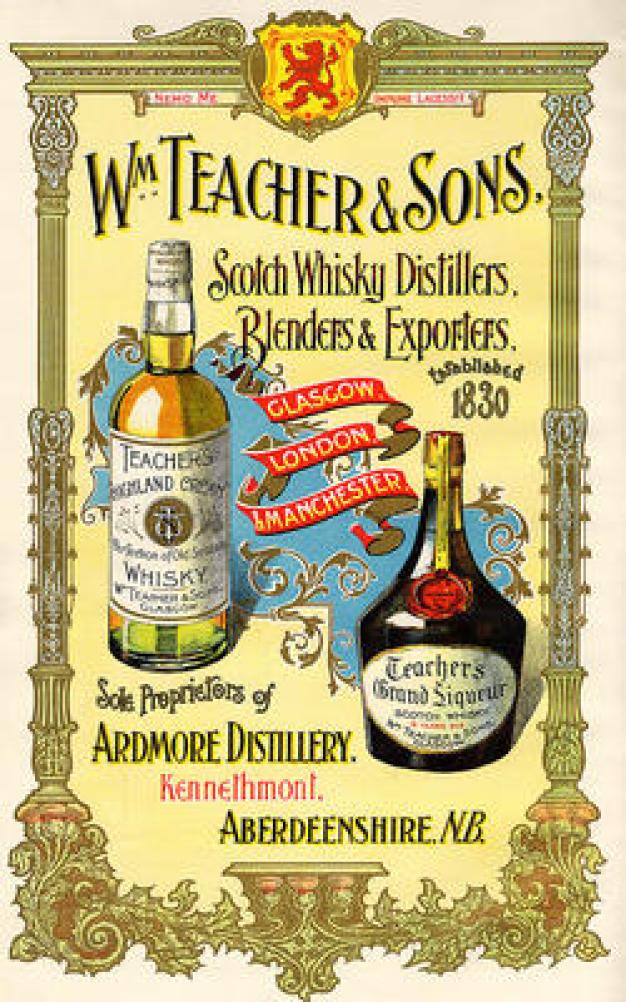

Another was Teacher’s Scotch Whiskey was established in Glasgow in 1830.

William Teacher established his whiskey product in 1830, and by the 1850s, began to open public houses known as “dram shops,” in which customers could drink whiskey.

The main attraction of the “dram shops” was their reputation for providing customers with high quality whiskey.

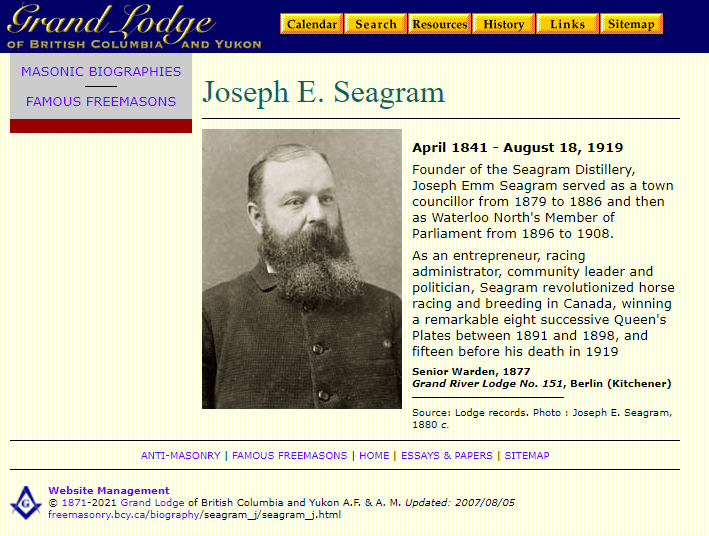

I can’t find a reference to William Teacher being a freemason, but Joseph Seagram, the founder of Seagram’s Distillery in Ontario, was one.

I have definitely come to believe that addictions like alcoholism were created and promoted intentionally to keep Humanity stuck in a diminished-level of consciousness.

This created the juxtaposition of a culture on one hand that encouraged the profuse consumption of alcohol, and at the same time a counterforce within that same culture that not only criticized alcohol consumption, but that got involved in “charitable institutions” with a stated mission of guiding the poor out of impoverishment supposedly caused by the character-weakness of alcoholism in many cases.

Just more food for thought.