This is the fourth part of an on-going series called “All Over the Place Via Your Suggestions” where I continue follow the many clues you all provide with your suggestions that helps to uncover our hidden history.

In Part 4 of this series, I looked into suggestions from viewers that took me primarily to Peoria, Illinois; Wabash & Fort Wayne, Indiana; and some water towers thereabouts; as well as many among other unexpected findings in my research of these places that are very telling, like the swamp between Fort Wayne and Lake Erie, and the sand dunes in Indiana between Fort Wayne and Lake Michigan.

What is interesting about doing this work following up on viewer suggestions is that more often than not, unplanned themes and correlations emerge that are unique to each part. I start out by selecting places people have suggested, and then I start looking to see what is there. I continue to find intriguing correlations and similarities in different places as you will see.

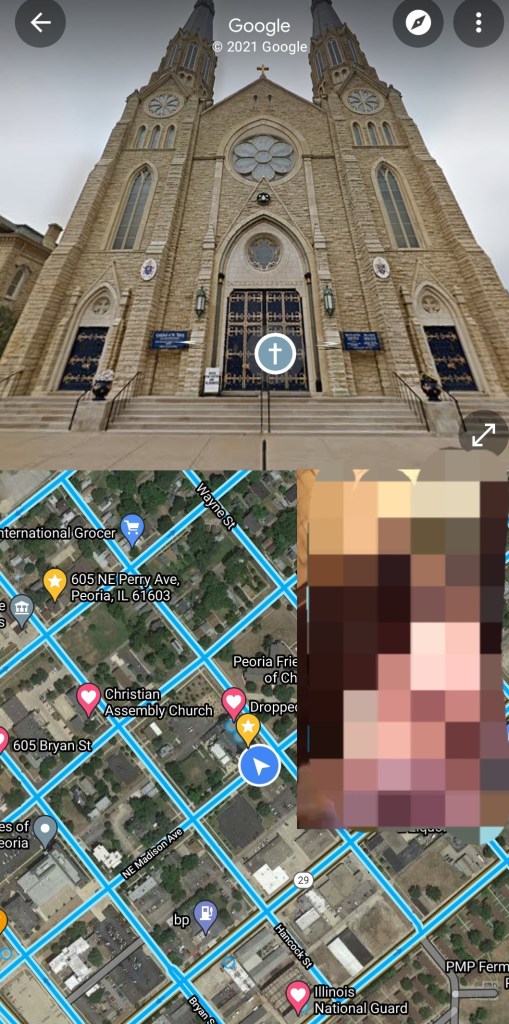

LR sent me screen captures on Google Maps of amazing structures she found in her new hometown of Peoria, Illinois, on a recent walkabout.

This is the Cathedral of St. Mary of the Immaculate Conception in Peoria.

It is the seat of the Diocese of Peoria.

The present Cathedral was said to have been constructed between 1885 and 1889, and designed by Chicago architect Casper Mehler in the style of St. Patrick’s Cathedral in New York City.

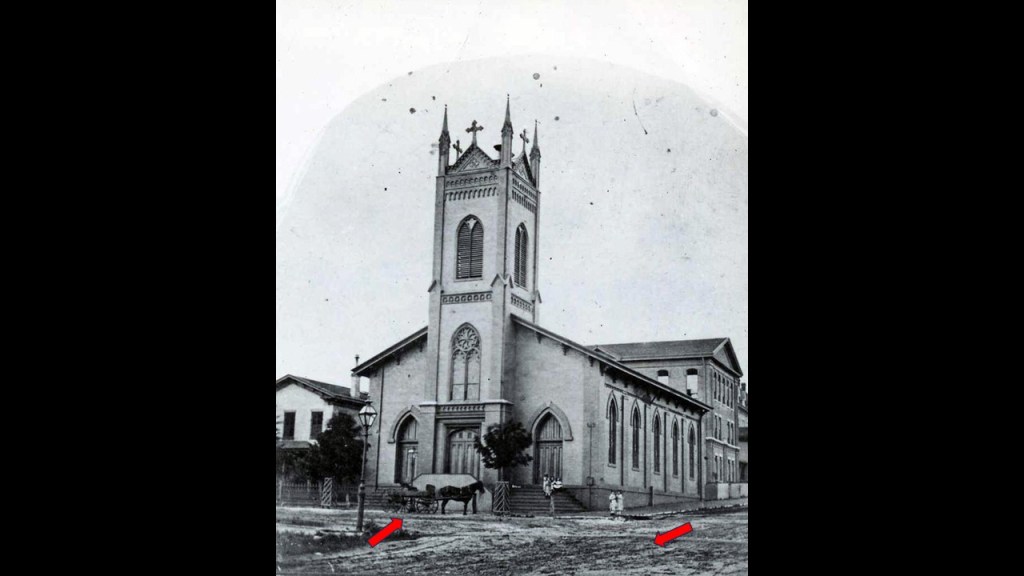

We are told that this is the church that was the first Cathedral of St. Mary’s, and was built in 1851.

This was said to be an 1858 photo of the first St. Mary’s showing one horse-and-buggy, and the streets beside it covered in dirt.

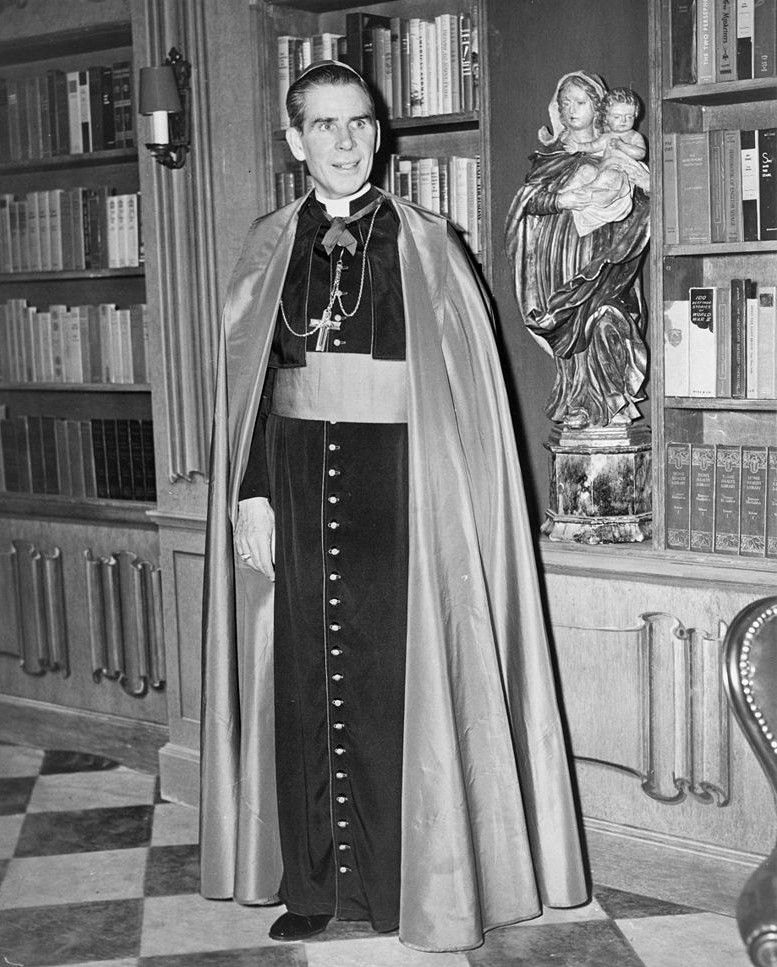

The Cathedral of St. Mary is also where Catholic televangelist Archbishop Fulton Sheen was ordained as a priest in 1919, and where his remains were interred in 2019 in the side altar of the Cathedral dedicated to Mary as “Our Lady of Perpetual Help,” from where he had been originally interred in St. Patrick’s Cathedral in New York City.

As “Father Sheen,” he hosted programs like “The Catholic Hour” on NBC radio from 1930 to 1950, and “Life is Worth Living” on television from 1952 – 1957.

He has been a candidate for sainthood since 2002, and while he has made it to the “Venerable” phase, he has not yet been beatified because of concern that his handling of a 1963 sexual misconduct case when he was the Bishop of Rochester might be cited unfavorably.

He left his position of Bishop of Rochester in 1969 and was made Archbishop of the Titular See of Newport, Wales.

A Titular See is a diocese that no longer functions, sometimes called a “dead diocese.”

It is interesting to note that when following up another commenter’s suggestion awhile back about Fulton, Missouri, I unexpectedly found Westminster College, where Winston Churchill’s Iron Curtain Speech was delivered in March of 1946 and the America’s National Churchill Museum is located.

America’s National Churchill Museum which was said to have been constructed from the deconstructed remains of St. Mary, Aldermanbury, a church in London that was attributed to Sir Christopher Wren between 1672 and 1679 after the Great Fire of London in 1666.

We are told that St. Mary, Aldermanbury, was ruined when it was hit by an incendiary bomb by the German Luftwaffe on December 29th of 1940, and was ultimately selected to be reconstructed in honor of Sir Winston Churchill at Fulton’s Westminster College, with 700 tons of stone being shipped to Fulton from London via boat and rail starting in 1965, and that the museum was finished and dedicated by May of 1969.

Two Fultons and two houses of worship named St. Mary’s coming up by following viewers’ places suggestions randomly?

Hmmm.

Here is the derelict Harrison School LR passed by on her walk.

Said to have been built in 1901, it has been abandoned for over ten-years, and on the list of buildings to be demolished.

It has become a dumping ground in the years since then.

Here is the Illinois National Guard Armory in Peoria that she shared a photo of from her walk.

Like the Harrison School, it is an abandoned building today.

This is what we are told about how this building came to be.

The Central City Railway Company won the contract from Peoria to handle the city’s streetcar business after offering to build a civic center-type building for the city and just give it to them, and of course the city couldn’t refuse their generous offer and awarded them the contract in 1901, and lo-and-behold, the city’s new Coliseum opened that same year with a nice ceremony and gala event!

Tragically, this Coliseum burned to the ground in 1920.

The Armory was said to have been built in the same place as the Coliseum as a place for the Illinois National Guard to train, and Peoria had a grand sports arena and convention hall.

But the Army National Guard stopped using it completely in 1995, after another installation was built in another location, and the building was abandoned, though there has been talk about it being brought back-to-life.

LR said while not included in the screen captures she sent, also of interest in the city is the Peoria High School, which was established in 1856 and said to be the second oldest continually operating high school west of the Allegheny Mountains after Evansville Central High School in Indiana.

The next place that I am going to visit from a viewer’s suggestion is Wabash, Indiana.

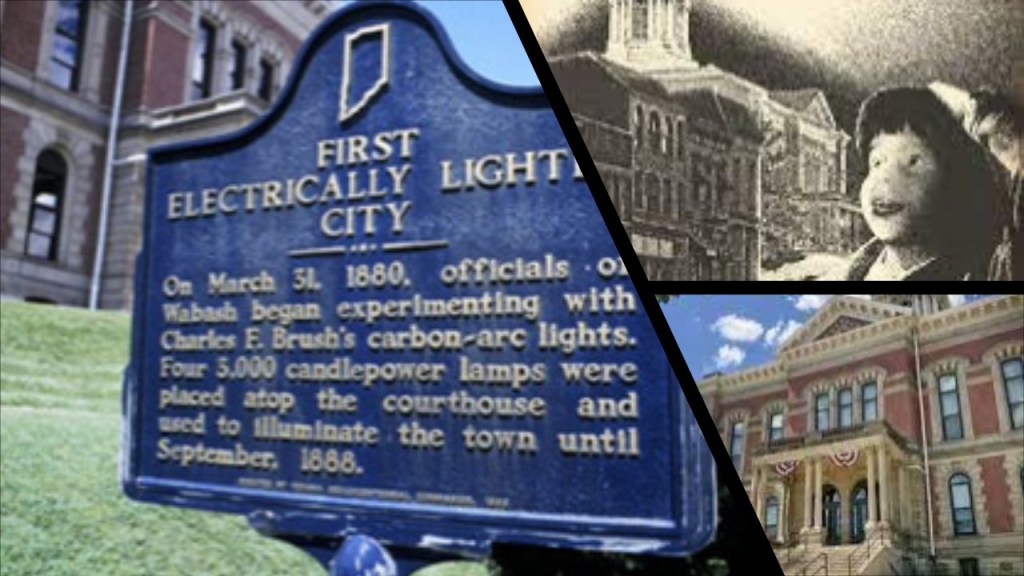

One of Wabash’s claims-to-fame is that it was the first electrically-lighted city in the world, when apparently the courthouse grounds were lit-up on March 31st of 1880.

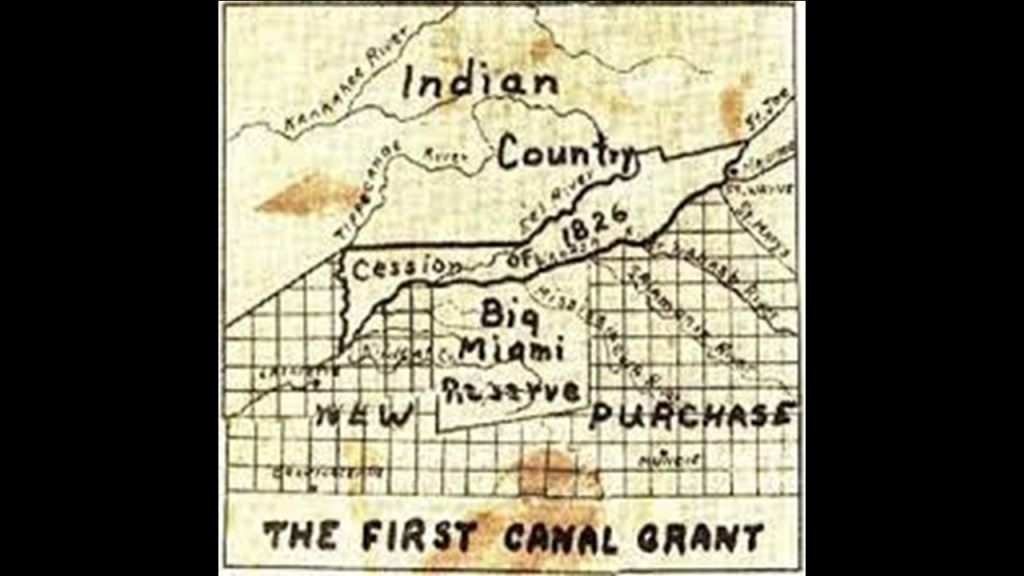

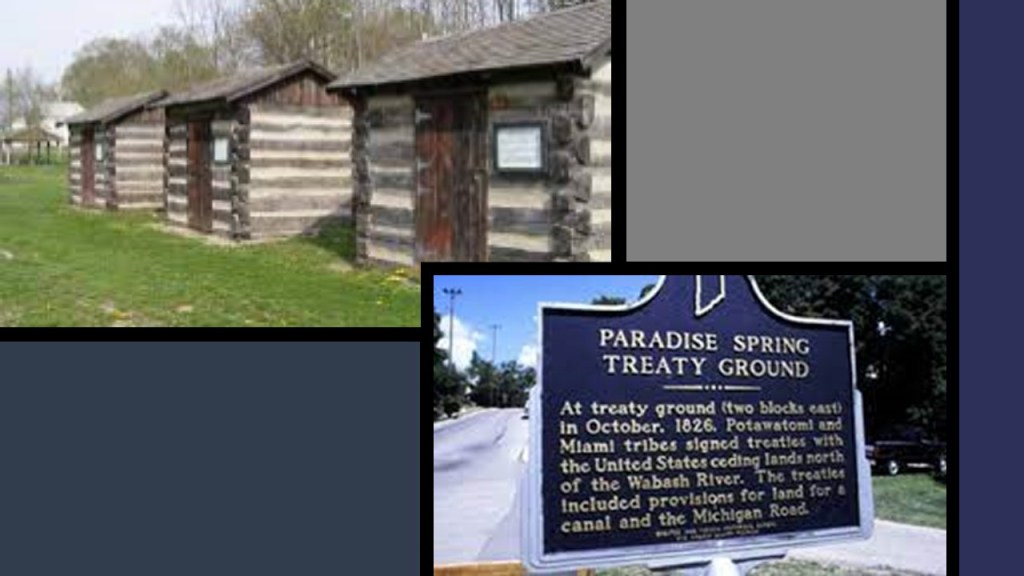

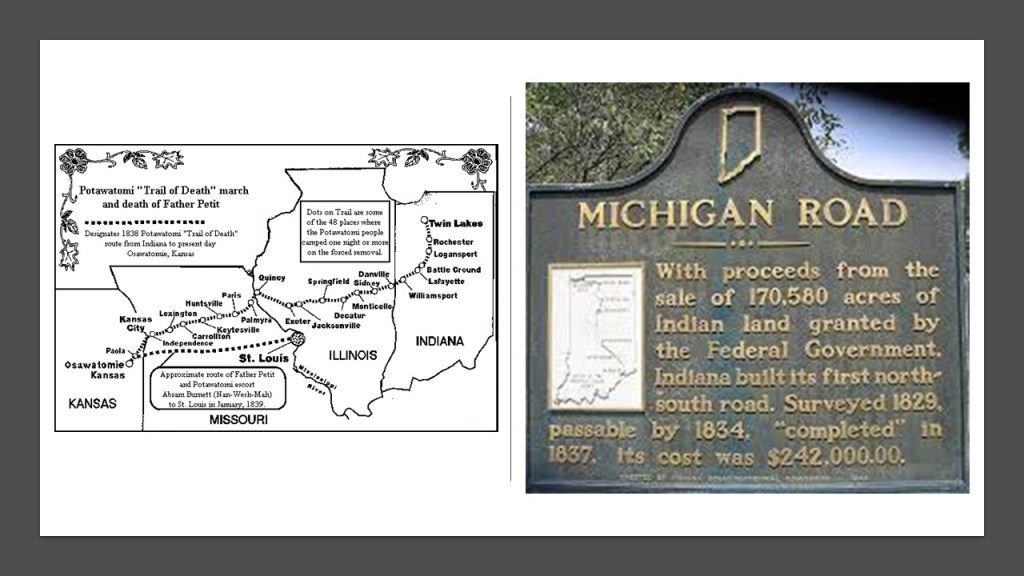

The 1826 Paradise Spring Treaty was signed by the Algonquin-speaking Miami and Potawatomi people with the United States, in which they ceded lands north of the Wabash River, with provisions for land for further white settlement including a canal and the Michigan Road.

These wooden shacks were erected in 1992 by the Indiana Historical Bureau and Wabash County Tourism at the Paradise Spring Treaty Grounds and Historical Park.

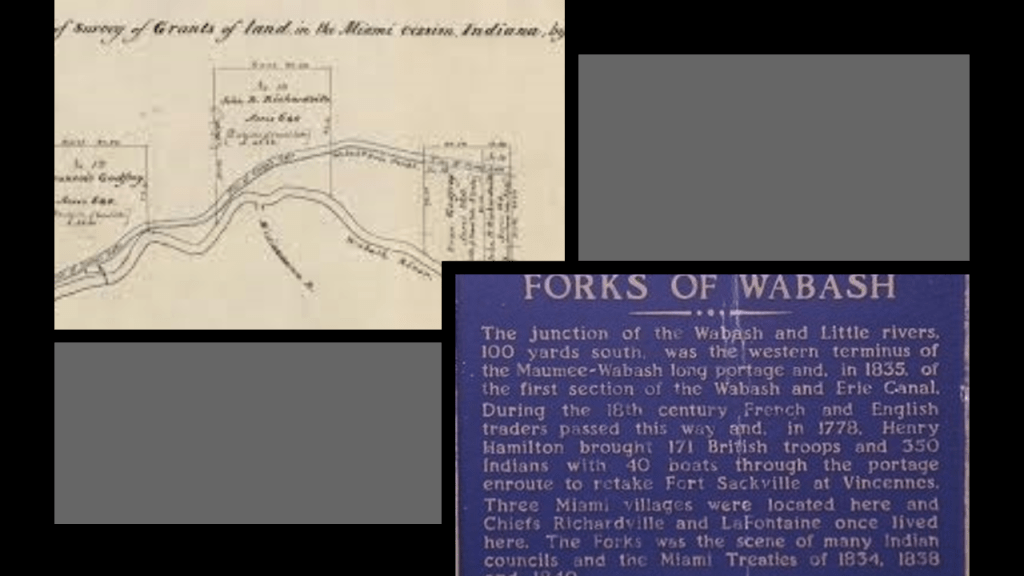

In 1834, the Treaty at the Forks of the Wabash was signed by the Miami people and others living in the Big Miami Reserve of north-central Indiana , in which they ceded certain land to the United States government in return for $280,000 and land-grants to certain Miami people, and a miller to run the mill for the Miami people’s use.

Wabash was first platted in 1834.

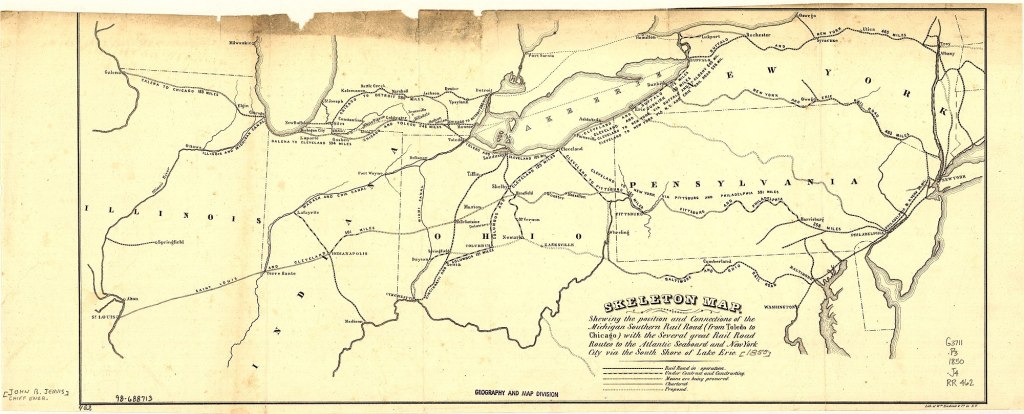

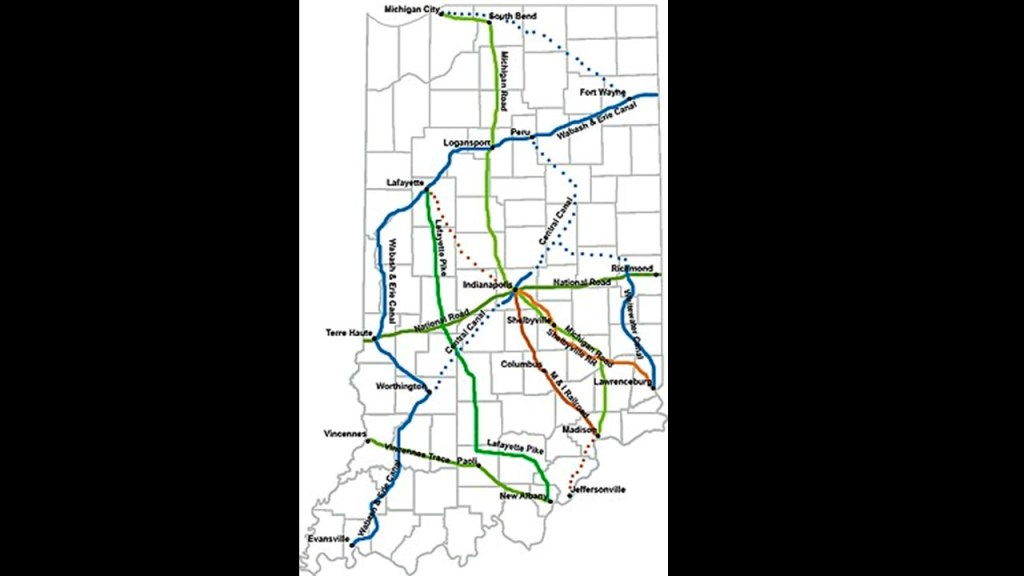

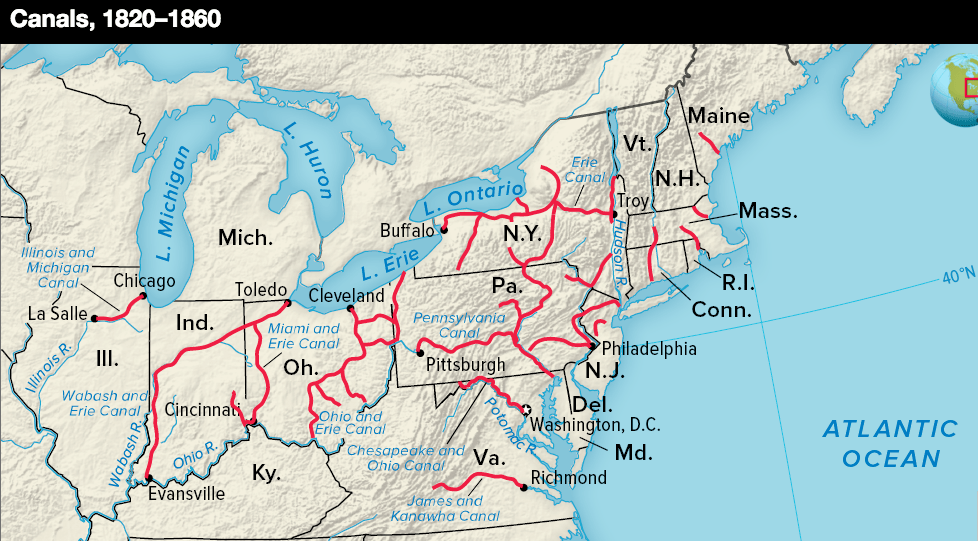

Said to have been built starting in 1832, the Wabash and Erie Canal ran from the eastern state line near Fort Wayne to Evansville on the Ohio River.

It connected with canals in northern Ohio which joined with the Erie Canal in Buffalo, New York.

At 468-miles, or 753-kilometers, from Toledo, Ohio, to Evansville, Indiana, the Wabash & Erie Canal was the second-longest canal in the world.

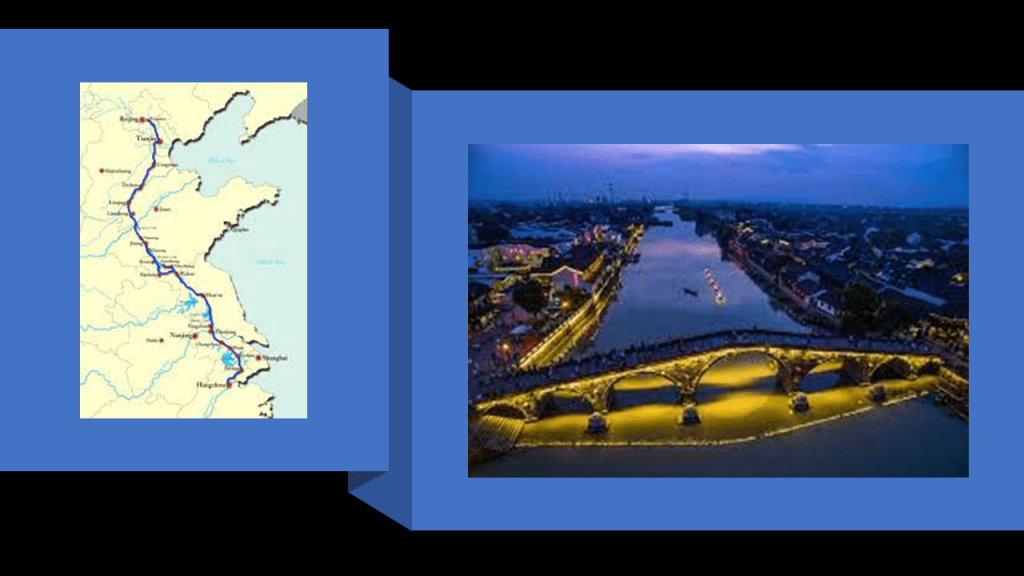

The Grand Canal in China is the longest canal in the world at 1,104-miles, or 1,776-kilometers, and the construction of sections of it are said to go way far back time to years given like 486 BC for the Han Canal section as an example.

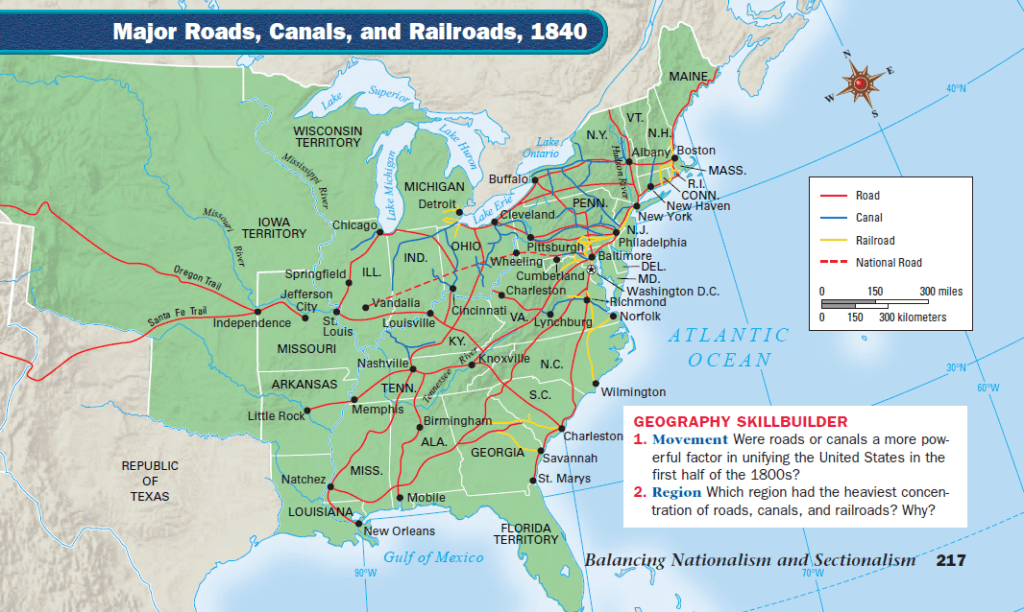

The Michigan Road was Indiana’s first “super-highway,” and said to have been constructed in the 1830s and 1840s between Madison, Indiana, and Michigan City, Indiana, by way of Indianapolis.

We are told that one of the things that made what became the Michigan Road possible was the concession of land by the Potawatomi in the 1826 Treaty, allowing for a ribbon of land that was 100-feet, or 30-meters, wide, stretching between Madison at the Ohio River and Michigan City on Lake Michigan.

Then, between September and November of 1838, the Potawatomi of Twin Lakes left the region by that same road when they were forcibly removed from their land by militia and relocated to Osawatomie, Kansas, in what became known as the “Potawatomi Trail of Death.”

We are told there were more than 40 deaths out of the 859 Potawatomie on the 660-miles, or 1,060-kilometers, forced march, with most of that number being children.

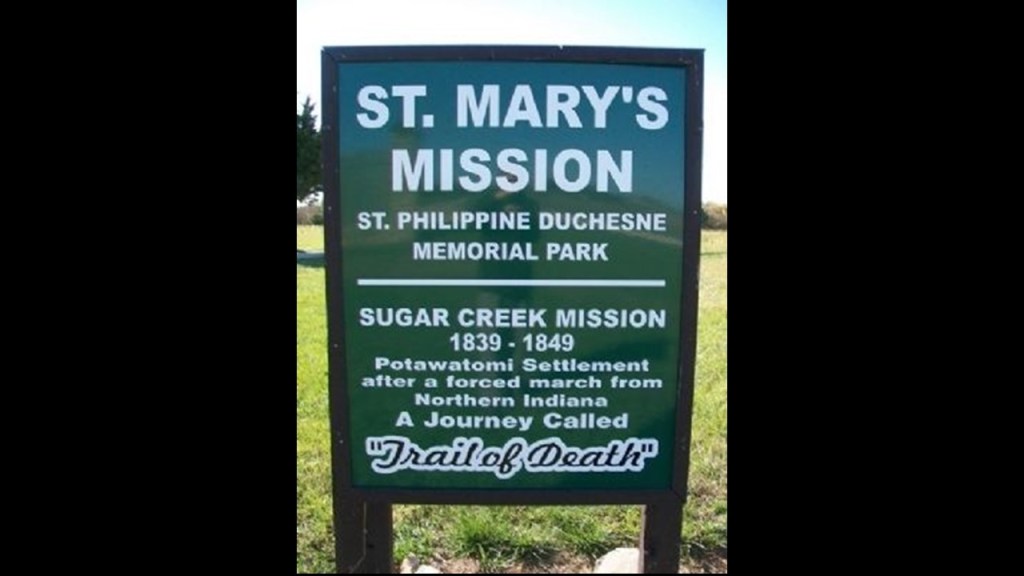

When they arrived in east Kansas, they ended up under the supervision of the Jesuit Father Christian Hoecken at what became the Saint Mary’s Sugar Creek Mission.

As seen in this map, Indianapolis is the central point of multiple transportation arteries emanating from it in a star-shaped pattern in all directions.

The ones that are named are: the Michigan Road; the Central Canal; the National Road, the first major improved highway in the United States built between 1811 and 1837 between Cumberland, Maryland, and Vandalia, Illinois; the Madison & Indianapolis (M & I) Railroad; and the Shelbyville Railroad.

The Central Canal was supposed to connect the Wabash & Erie Canal to the Ohio River.

We are told that this canal-building project was initially funded by the 1836 Indiana Mammoth Internal Improvement Act that added $10-million to spending on trasnportation -related projects, of which the Central Canal project received $3.5-million.

The following year, the Panic of 1837 adversely affected the state’s economy, and the building of the canal stopped completely in 1839, with only 8-miles, or 13-kilometers, completed and an additional 80-miles, or 130-kilometers, partially-built between Anderson and Martinsville.

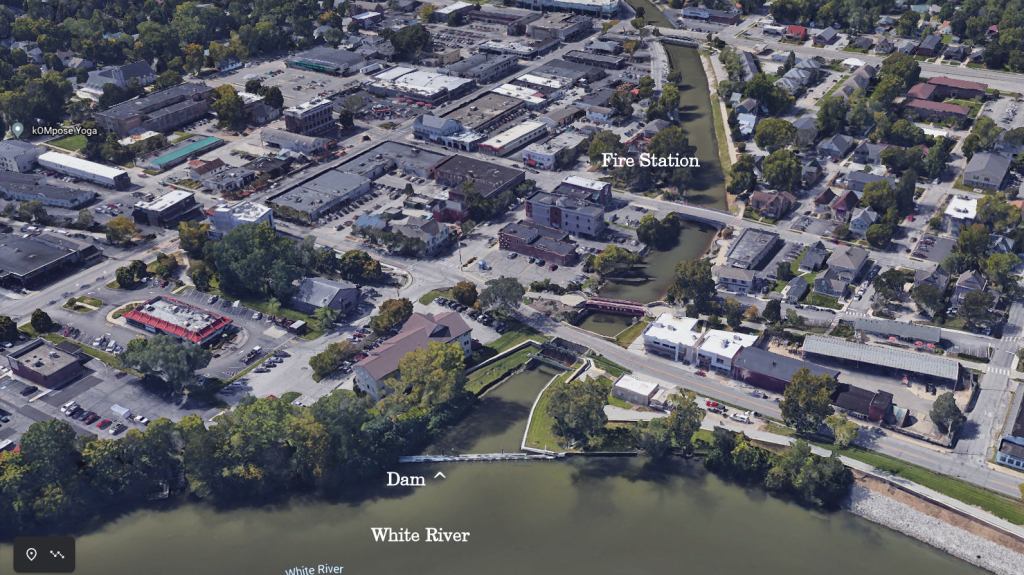

We are told the 8-fully completed miles were entirely within the Indianapolis section of the canal and paralleled the White River.

We are told that water was first drawn into the Central Canal by the feeder dam on the White River in Broad Ripple starting in 1839.

Keep in mind that on the one-hand, we are told that life in America in the 1830s was largely rustic and full of social ills in need of reform…

…and on the other hand, we are told the North American Canal Age of canal-building was dated from 1790 to the mid-1800s.

We are also told that the construction of the railroads started in the same period, and simultaneously the railroads were already starting to make the canals they were constructing obsolete because they were so much faster and more efficient!

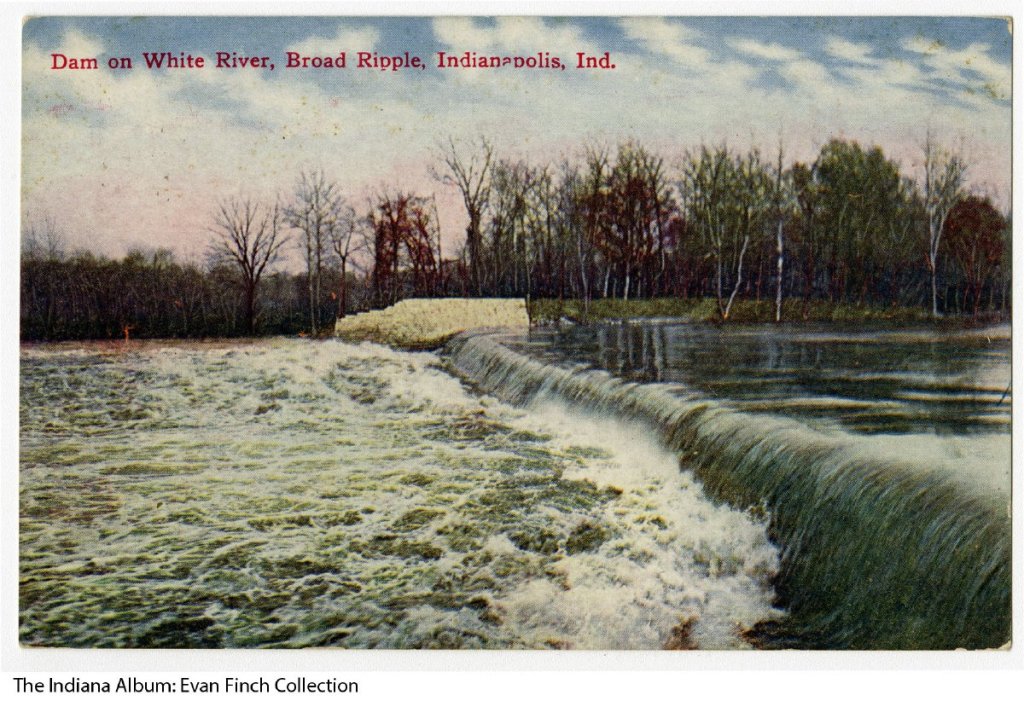

This is a 1909 postcard of the White River dam in Broad Ripple.

We are told that starting in the last-half of the 19th-century, a number of water companies used the section to power Indianapolis’ water-system.

In 1904, the Indianapolis Water Company used the canal as the source of power for a water purification plant, the West Washington Street Pumping Station, until 1969.

The West Washington Street Pumping Station was said to have been built between 1870 and 1871.

It currently houses the offices of the White River State Park.

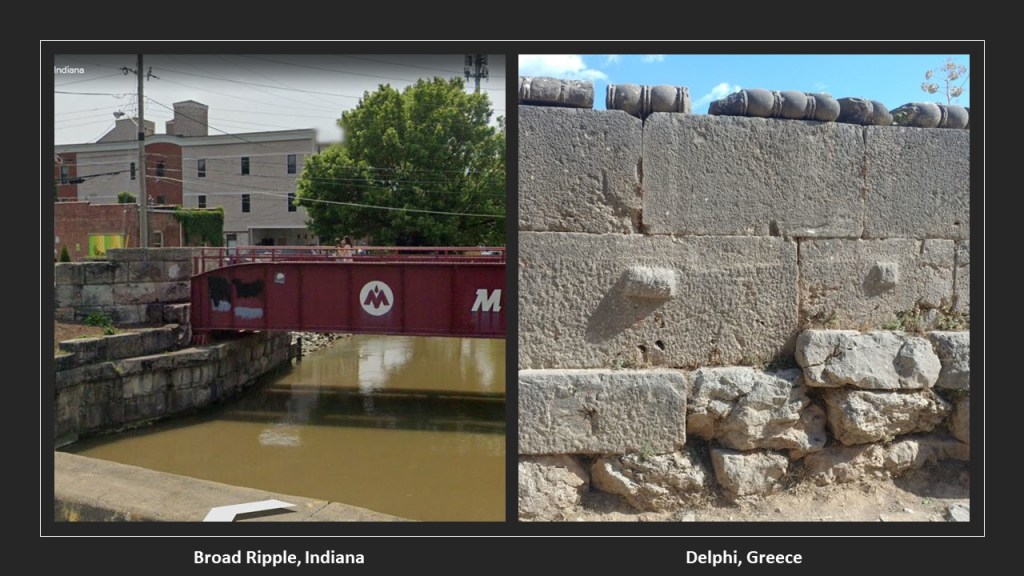

This is a view of the Central Canal, with cut-and-shaped large stones, and the Monon railroad bridge crossing over it, on the left, and on the right is a photo for comparison of an ancient megalithic stone wall in Delphi, Greece.

Here’s another view of the large stonework of the Central Canal from Broad Ripple’s Rainbow Bridge.

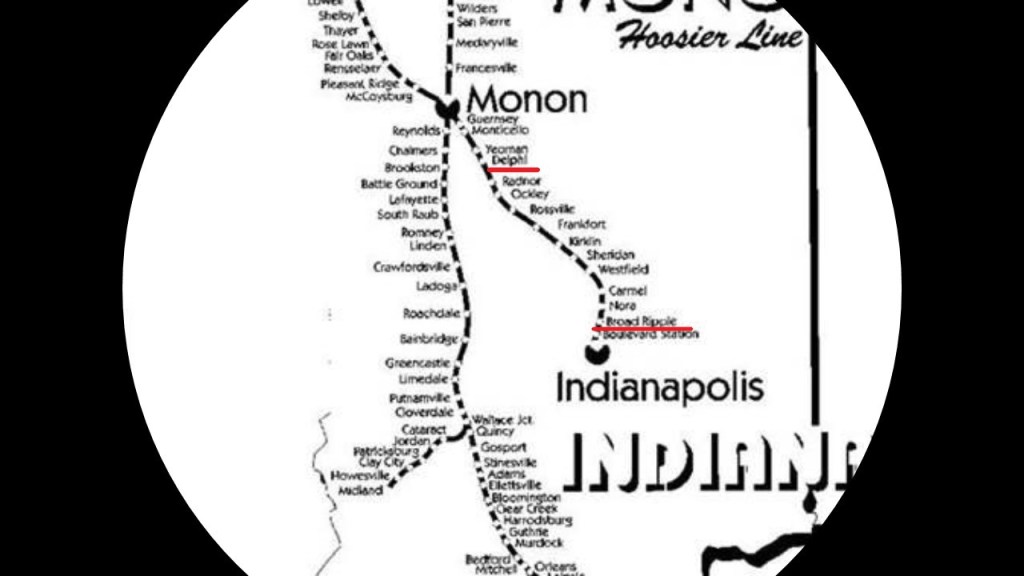

The Monon Trail used to be the Monon rail-line between Indianapolis and Delphi, Indiana, that was abandoned in 1987, and which was part of a larger rail-line that connected Chicago and Indianapolis.

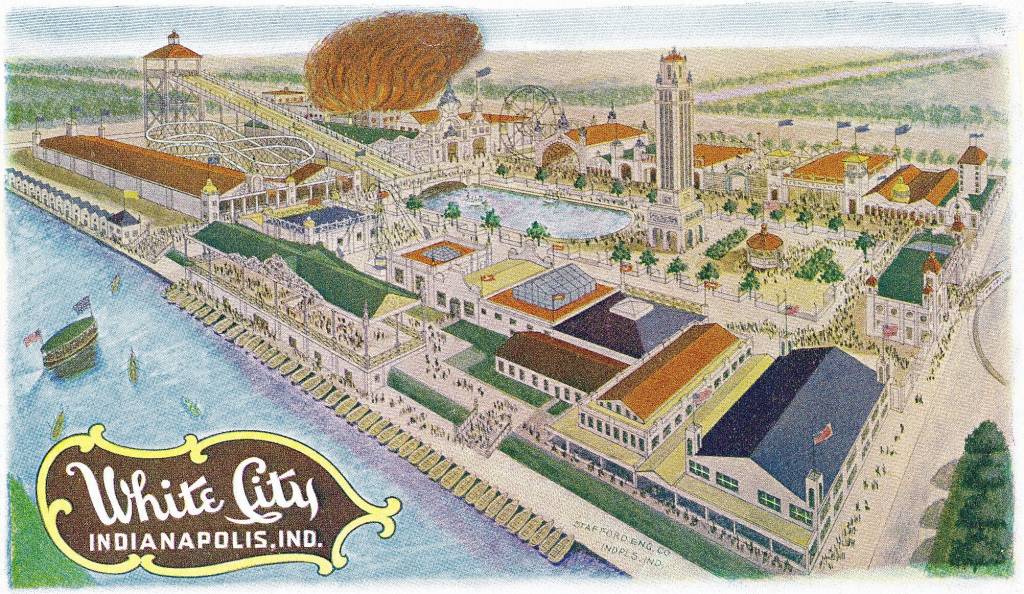

The organizers of the Broad Ripple Transit Company in 1894, what was called the first electric interurban railway to be constructed and put in operation in the United States, created the White City of Indianapolis Company in 1905, with the stated goal of developing an amusement park at the end of the Broad Ripple Transit Company’s College Line.

The White City Amusement Park, said to have been named in honor of Chicago’s 1893 Columbian Exposition, which was also known as the White City, opened officially on May 26th of 1906.

The 4-acre pool was scheduled to open to the public on June 27th of 1908, but on June 26th, 2 years and a month to the day, nearly the whole amusement park was burned to the ground, allegedly taking less than 10-minutes to engulf the park.

The pool, however, remained unscathed by the fire.

The Union Traction Company purchased the park in 1911, and continued on as the Broad Ripple Amusement park until around 1945…

…and the location was Broad Ripple City Park today.

We are told the Madison and Indianapolis Railroad was the first operable steam railroad completed in Indiana, and one of the first west of the Allegheny Mountains, with its construction beginning in 1836 with the passage of that Indiana Mammoth Internal Improvement Act.

The project was said to have encountered serious financial difficulties, and turned over to a private company in 1842.

Work continued on the 86.5-mile, or 139-kilometer, long line over the next 5- years, arriving in Indianapolis in 1847 and the beginning of the rail-line’s use for freight service.

What started out as the Madison and Indianapolis Railroad is still in use today by other railroads, with the exception of the abandoned 17-mile, or 27-kilometer, section of the railroad running from North Vernon to Columbus.

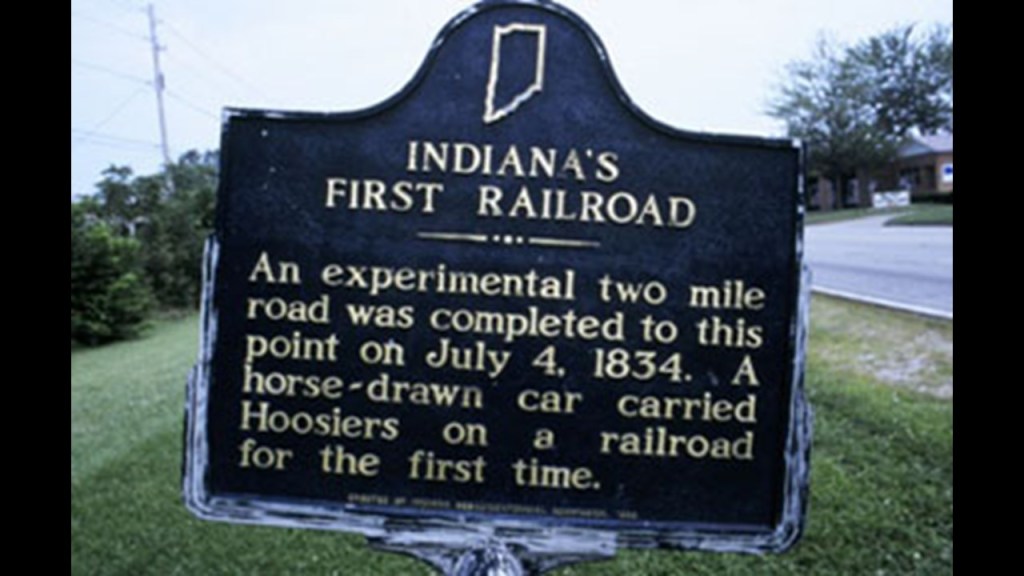

With regards to the Shelbyville Railroad line marked going to Indianapolis on the earlier transportation artery maps, the only thing I can find in reference to Shelbyville and a railroad is this sign that is located east of downtown Shelbyville memorializing “Indiana’s First Railroad,” memorializing the completion of 1) an experimental 2-mile, or 3-kilometer, long road on July 4th of 1834, and 2) a horse-drawn car carrying Hoosiers on a railroad for the first time.

GS just now left me a comment to include water towers as components of the physical infrastructure of Earth’s grid system, along with the railroads, canals, waterfalls, and roads that I have been looking at so far in this post and in my last post.

GS suggested they might have been connected to tunnels below, or were some kind of Tesla energy harvesters.

They are definitely noteworthy and in no way fit the narrative we have been given.

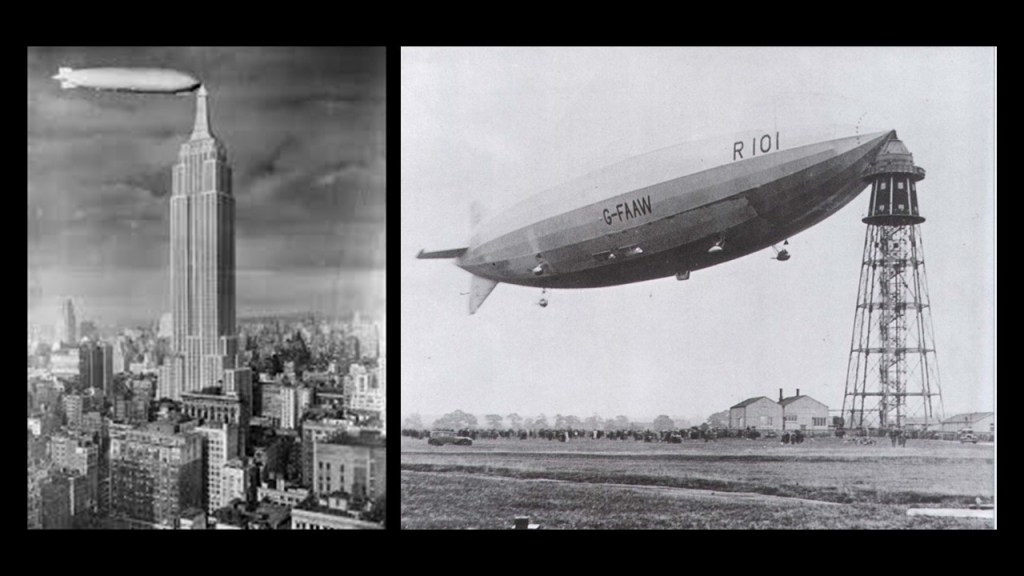

I have also seen depictions of water towers and other tall buildings including the Empire State Building, as docking stations for airships once upon a time.

Whatever their original function was, we certainly haven’t been told the truth about them!

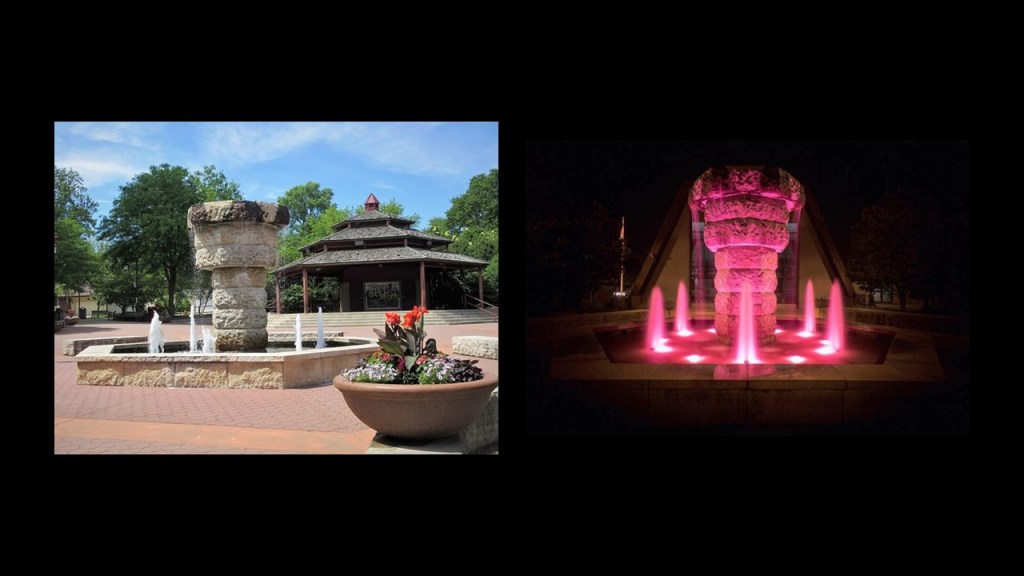

Going back to where I started in Peoria, Illinois, I found this water tower in Peoria Heights which is still standing today.

It is a still-functioning water tower on top of 500,000 gallons of clean well-water that is 200-feet, or 61-meters, high with a glass elevator going to three observation decks at the top, and said to have been built in 1968.

There is also a gazebo at Tower Park, and a fountain with old stonework that lights-up right next to the water tower.

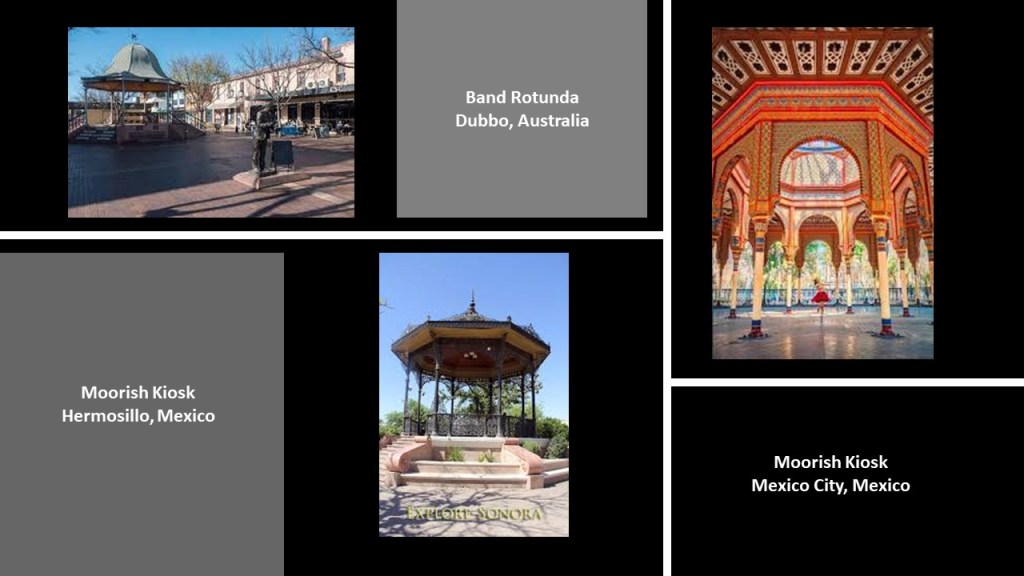

I have long suspected these gazebos, also called by different names like bandstands and kiosks, to be part of the original civilization as well because I have encountered them in my research all over the world.

Like the band rotunda in Dubbo in New South Wales Australia on the top left; the Moorish-style Kiosk in the Plaza Zaragoza in Hermosillo, Mexico, in the bottom middle; and the piece-de-resistance Moorish Kiosk in Mexico City, Mexico on the right.

DZ suggested Fort Wayne, Indiana, so I’ll head in that direction and take a look.

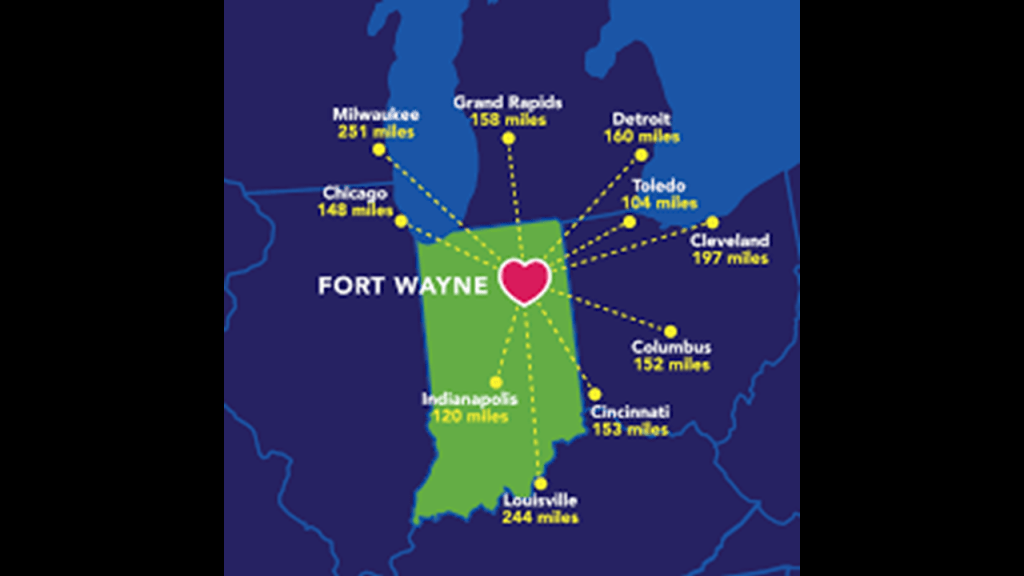

Fort Wayne is located in northeastern Indiana, 18-miles, or 29-kilometers, west of the Ohio border, and 50-miles, or 80-kilometers south of the border with Michigan.

Indiana’s second-largest city after Indianapolis, apparently Fort Wayne is centrally-located between ten major cities as well.

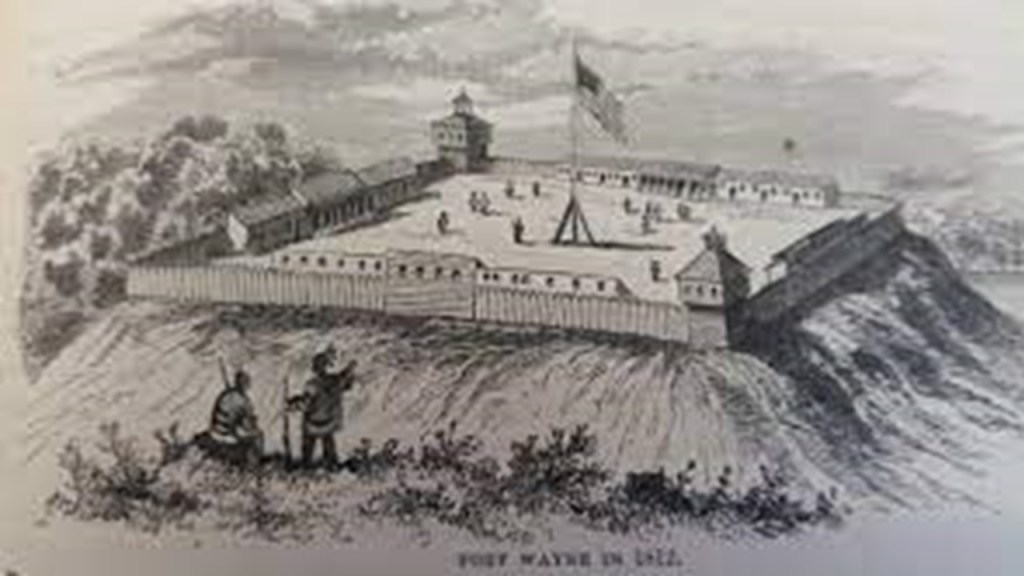

We are told that the original fort at Fort Wayne was built in October of 1794, the last in a series of forts built near Kekionga, after General Anthony Wayne’s defeat of the Miami of the western confederacy at the end of the Northwest Indian War and the beginning of U. S. occupation of the Northwest Territory.

Kekionga was the principal city of the Miami and Shawnee tribes, located at the confluence of the St. Joseph and St. Mary’s Rivers to form the Maumee River.

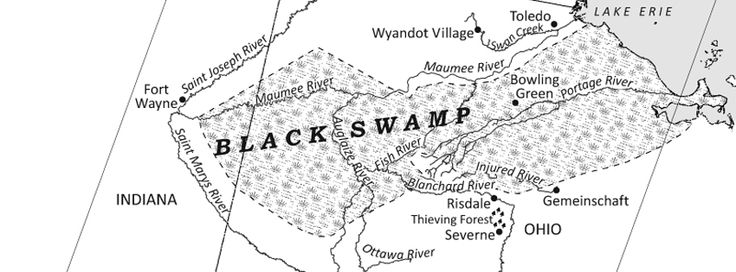

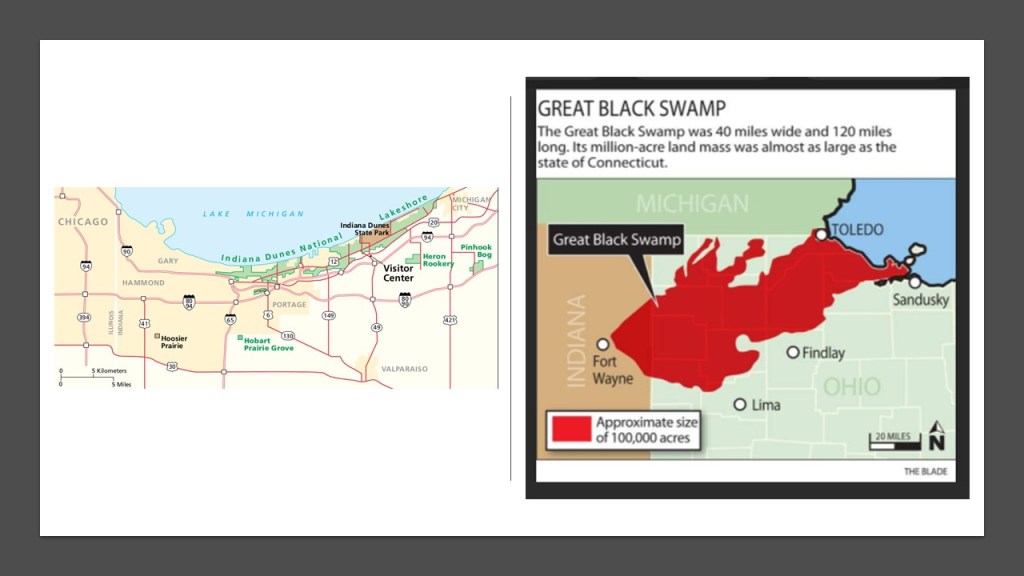

It is on the edge of the Great Black Swamp in present-day Indiana, and the land once covered by the swamp encompasses northeastern Indiana as well as northwest Ohio in the Maumee and Portage Rivers’ watersheds.

Since the 1850s, efforts to drain the swamp began in earnest for agricultural and transportation use.

We are told that the vast swamp with a network of forests, wetlands, and grasslands, with deciduous swamp forests of ash, elm, cottonwood, sycamore, beech, maple, basswood, tulip tree, oak and hickory.

Back to Fort Wayne.

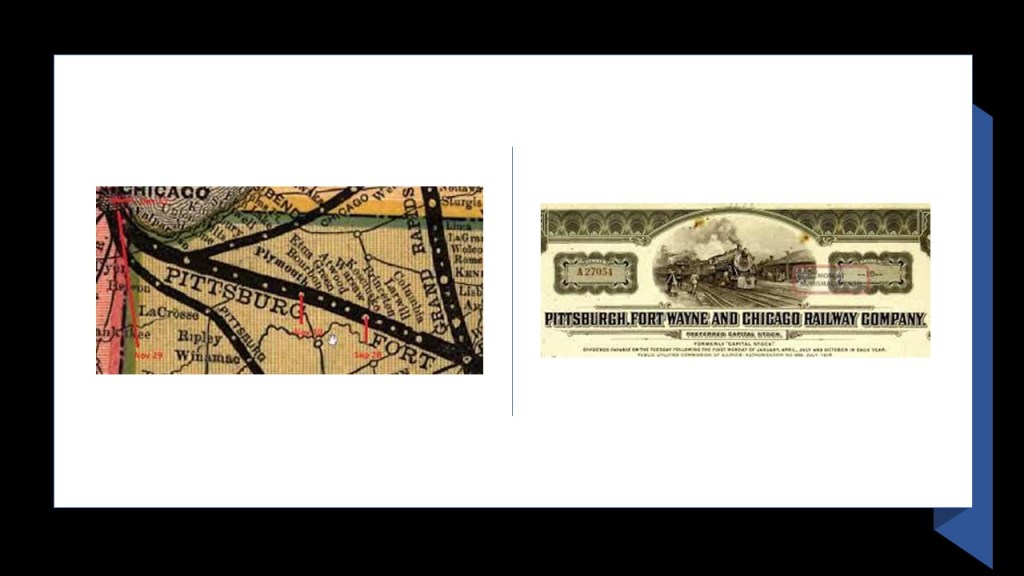

We are told the town underwent tremendous growth when the Wabash & Erie Canal was completed in 1853.

But then, we are told that the canal quickly became obsolete only a year later when the Pittsburgh, Fort Wayne & Chicago Railway was completed in 1854.

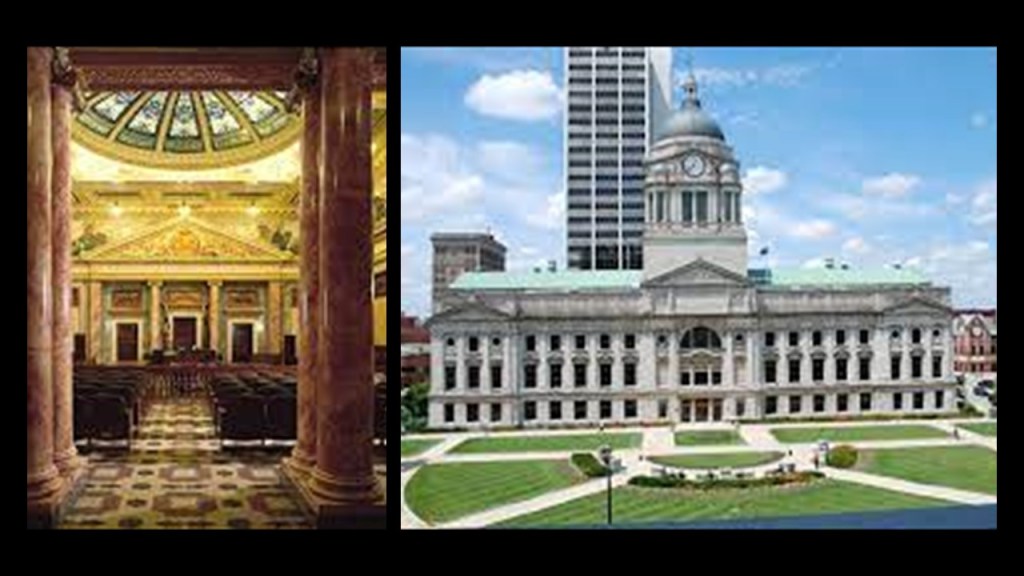

A museum today, the Old City Hall in Fort Wayne was said to have been built in the early 1890’s, designed by local architects John Wing and Marshall Mahurin in the Richardsonian Romanesque style of architecture

The Allen County Courthouse in Fort Wayne was said to have been built between 1897 and 1902, and a significant example of Beaux-Arts Architecture designed by local architect Brentwood S. Tolan, who we are told had no formal education as an architect but was apprenticed to his father, who was a marble craftsman-turned architect.

Tolan was also credited with the design of the Whitley County Courthouse in Columbia City, Indiana, said to have been constructed in the French Renaissance architectural style in 1888…

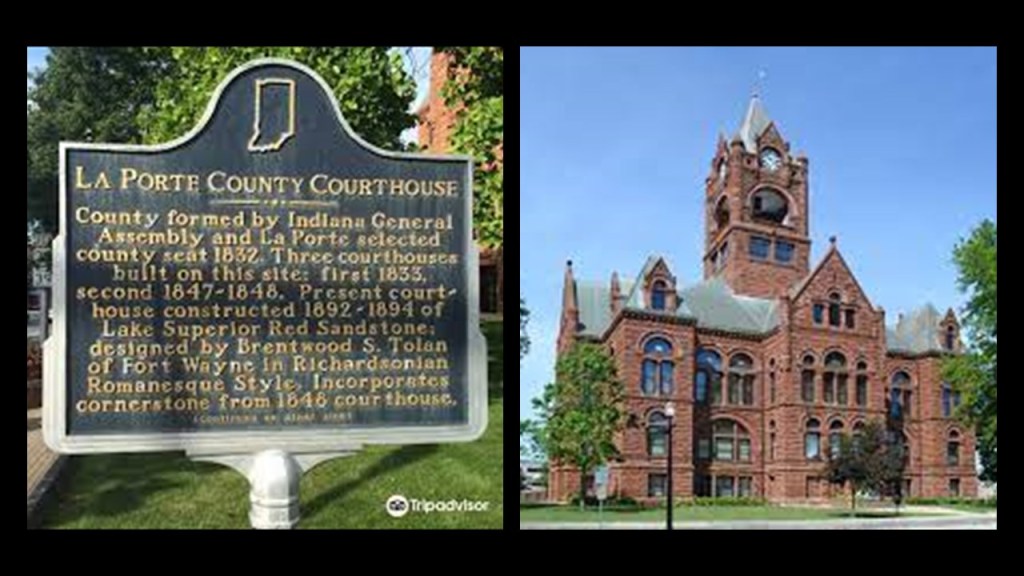

…and the La Porte County Courthouse in La Porte, Indiana, built between 1892 and 1894 in the Richardsonian Romanesque architectural style.

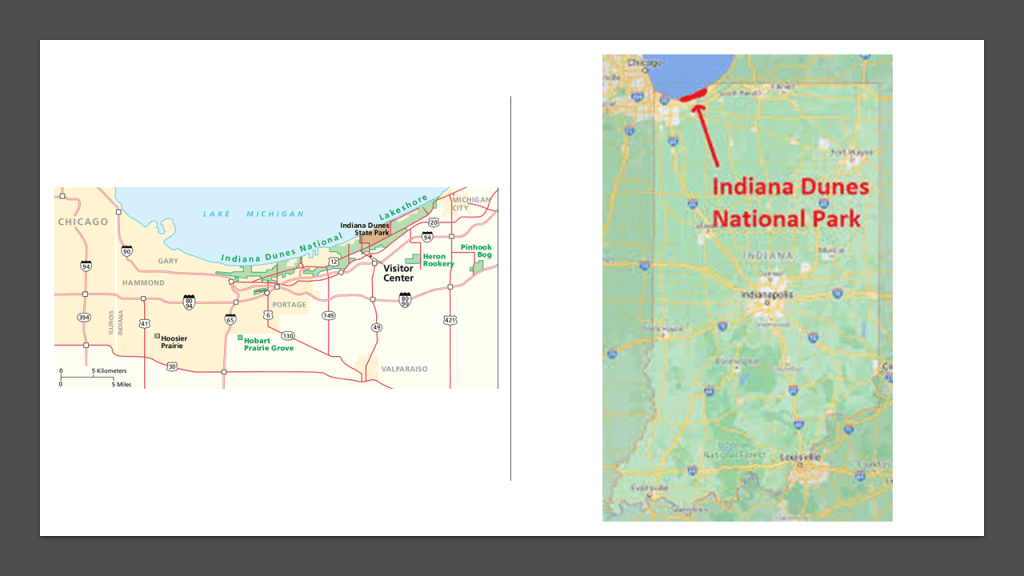

The Indiana Dunes are northwest of Fort Wayne on the shores of Lake Michigan, and designated as the nation’s newest National Park in February of 2019, running along 20-miles, or 32-kilometers, along the southern shore of Lake Michigan.

It had been designated as a National Lakeshore by Congress in 1966.

The Cleveland-Cliffs Steel Plant is located on the west side of the Indiana Dunes National Park.

Operated by Cleveland-Cliffs Inc, It is the world’s largest producer of flat-rolled steel in North America.

The company’s predecessor was the Cleveland Iron Mining Company, which was first founded in 1847 and chartered as a company in Michigan in 1850.

Industrialist Samuel Mather, co-founder of a shipping and mining company, and several of his associates had learned of rich iron-ore deposits in Michigan’s Upper Peninsula and soon afterwards the Soo Locks opened in 1855, allowing for the shipping of iron ore from Lake Superior to Lake Michigan.

Michigan City, Indiana, the northern terminus of what was originally the Michigan Road, is on the other side of the Indiana Dunes on the southern shore of Lake Michigan.

The Michigan City Power Plant is west of the city’s downtown on the Lakeshore next to the dunes, and while it is not a nuclear power plant, it is coal-burning plant that looks like one.

While we are told there is little evidence of permanent Native American communities here, but evidence instead of seasonal hunting camps, there have been five groups of mounds documented in the dunes area.

So the Indiana Dunes are to the northwest between Fort Wayne and Lake Michigan, and the Great Black Swamp is to the northeast between Fort Wayne and Lake Erie.

Hmmm. Imagine that! Ruined land in both directions.

I absolutely believe there is much waiting to be discovered from the original civilization underneath all that sand and all that land!

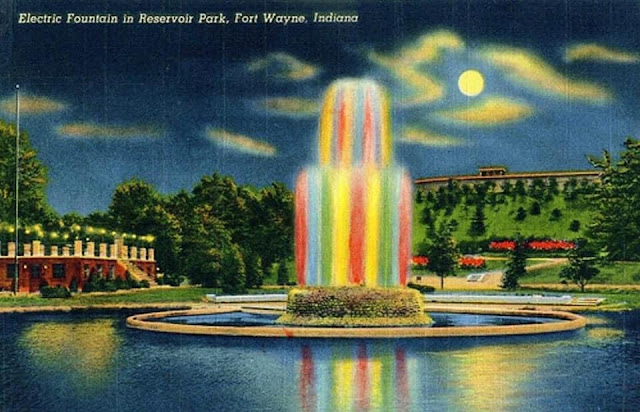

With regards to water towers, Fort Wayne didn’t have a tower, it had a reservoir on a mound apparently, said to have been constructed in 1880.

There was even an electric, lighted water fountain at the city’s Reservoir Park…

…which was replaced by something mundane in comparison.

Before I end this blog post, I am going to take a look at several other water towers that I came across in Indiana

The Remington Water Tower in Remington, Indiana, was said to ahve been built in 1897, after the town contracted with the Challenge Wind Mill and Feed Mill Company of Batavia, Illinois, to build a tower connected to the new town hall since the town had finally grown large enough since its founding in 1860 to need a public water tower.

The only remaining brick water tower with a wooden tank left-standing in Indiana, it has a limestone foundation, 24-inch, or 610-millimeter, thick brick walls; it is 104-feet, or 32-meters, tall; and is topped by a 66,000-gallon or 249,837-liter, cypress water tank that is filled by gravel today, as the water tower stopped being used as a water reservoir in 1984.

The building next to the water tower previously served as a town hall, fire station, and jail. Today it is used as a municipal parking garage.

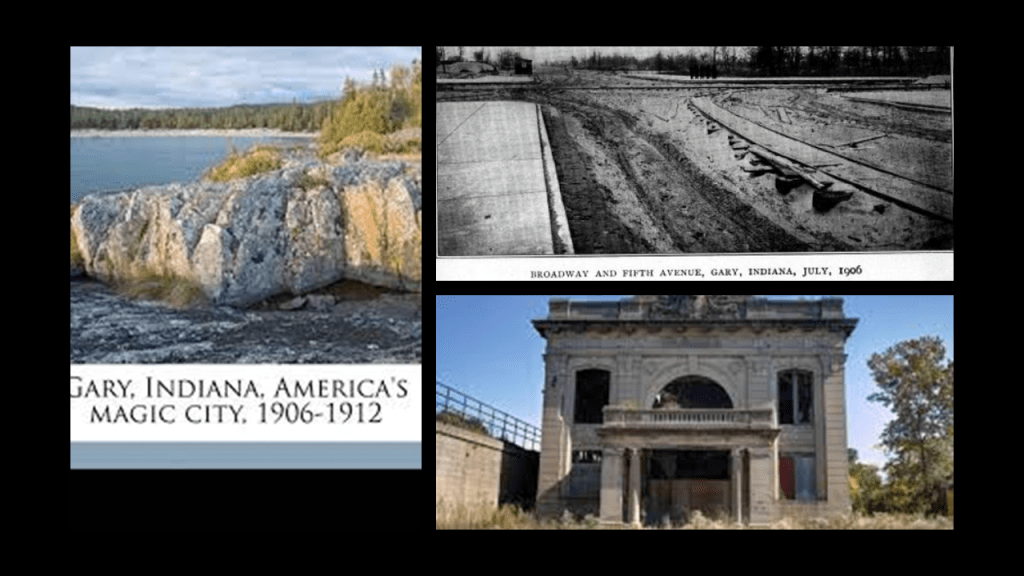

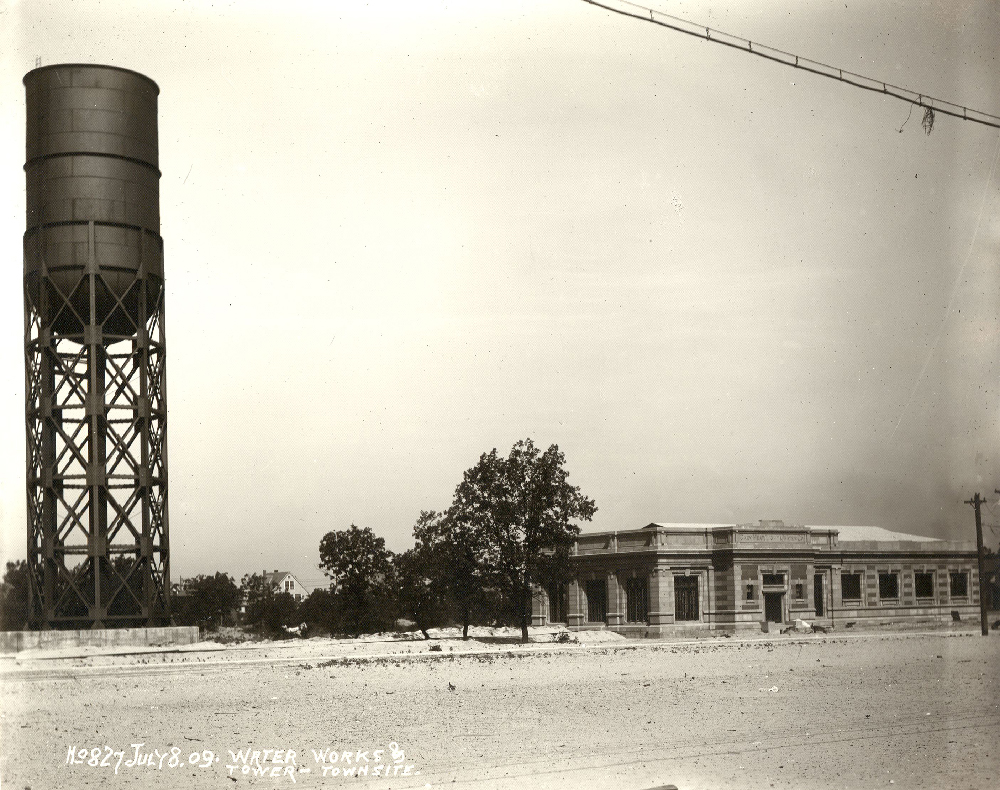

The water tower in Gary, Indiana, was said to have been built by the Gary, Heat, and Light Company and completed in 1909 as part of the infrastructure for waterworks for the new city that had been transformed from sand dunes, earning it the nickname “Magic City” to become “Steel City.”

This is what we are told.

Gary’s original water tower was 30-feet, or 9-meters, in diameter, on eight 90-foot, or 27-meter, tall steel columns.

Then, the Gary, Heat, and Light Company added a concrete block shell to cover the exposed steel skeleton, complete with cornices and parapets.

The Beaux-Arts pumphouse beside the water tower no longer exists…

…but the water tower is still in use today by the Indiana American Water Company.

I am going to end this post here, and will continue to investigate your suggestions in the on-going series “All Over the Place via Your Suggestions.”